Abbreviations

Bistris, 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)-1,3-propanediol; DEA, 2-(N,N-diethylamino)diazenolate 2-oxide; deoxyHb, HbFeII; ferrylHb, oxoiron(IV) hemoglobin; sGC, soluble guanylyl cyclase; GSH, glutathione; GSNO, S-nitrosoglutathione; Hb, hemoglobin; HbFeIINO, nitrosyl hemoglobin; Mb, myoglobin; metHb, HbFeIII; MHMA, (Z)-1-{N-methyl-N-[6-(N-methylammoniohexyl)amino]}diazenium 1,2-diolate; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; oxyHb, HbFeO2; R, relaxed, RBCs, red blood cells; SNOHb, hemoglobin with the cysteine residue β93 nitrosated; T, tense.

1 Hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (Hb) is probably the most thoroughly studied protein in the human body. At the beginning it was the ease of hemoglobin purification from many organisms and its stability that drove researchers to the field. Later, this protein proved to be a very complex system with fascinating properties that still remain a challenge to its investigators. Human hemoglobin is among the first proteins for which the structure was determined by X-ray crystallography [1]. Hemoglobin is a tetramer of two α- and two β-subunits, each of which contains an iron protoporphyrin IX–heme. The characteristic globular hemoglobin structure, the so-called globin fold, arises from the numerous α-helices that are formed when the two polypeptide chains fold: the α-chains have seven helices whereas the β-chains have eight. The function of hemoglobin is to bind O2 in the lungs and deliver it to peripheral tissues. In addition, hemoglobin transports the waste product of cellular metabolism – CO2 – to the lungs, so that it can be exhaled.

Oxygenation of hemoglobin is cooperative. This means that binding of the first O2 molecule to the heme of a subunit facilitates subsequent binding of other O2 molecules to the remaining subunits in the tetramer. The binding affinity for O2 is also regulated by allosteric effectors, such as pH (Bohr effect), CO2- and 2,3-diphosphoglycerate-concentration [2]. In a simplified description, cooperative O2 binding can be explained by a switch of the protein from a tense (T) low-affinity state in the deoxygenated form to a relaxed (R) high-affinity state in its oxygenated form. A large number of structural, mutagenesis, and kinetic studies carried out over the last three decades have allowed to reach a good understanding of the transitions that take place at the atomic level when T-state hemoglobin is converted to its R-state [3].

Recently, it has been discovered that the hemoglobins found in vertebrates derive from an ancient protein family present in essentially all living systems, among others in bacteria and plants [4]. All these hemoglobins are characterized by the typical α-helix-rich globin fold. A common function attributed to a large number of hemoglobins is to protect against reactive nitrogen species, specifically to scavenge nitrogen monoxide. Interestingly, also human hemoglobin has recently been proposed to manifest an additional function related to the biochemistry of NO•.

2 NO• and the blood vessels

The discovery that nitrogen monoxide is involved in a diverse array of physiological and pathophysiological processes opened a completely new research area. In vivo, NO• is generated from the essential amino acid l-arginine by a family of enzymes called nitric oxide synthases (NOS) [5,6]. Among others, NO• is fundamental for signal transduction in the nervous system and in immune responses. In addition, endothelium-derived NO•, generated by the endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), is a key determinant of blood pressure homeostasis [7]. NO• produced in vascular endothelial cells can diffuse across cell membranes to the adjacent smooth muscle cells where it activates its target enzyme, the soluble isoform of guanylyl cyclase (sGC). Binding of NO• to the reduced heme of sGC leads to an increase of the intracellular concentration of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), a compound that triggers a series of reactions that finally cause smooth muscles to relax.

NO• generated by another isoform of NOS, the inducible NOS (iNOS), also plays an important role in the cardiovascular system, in particular in the response to vascular injury. Indeed, NO• has been shown to inhibit platelet aggregation and adherence to the site of injury, and consequently to preserve blood flow [8]. In addition, as arterial injury results in loss of eNOS, upregulation of iNOS may also represent a protective mechanism that compensates for the loss of the endothelium [9].

3 Hemoglobin and NO•

Hemoproteins are among the main targets of NO• in biological systems. NO• can react with all forms of hemoglobin found under physiological conditions (reactions (1)–(4)). DeoxyHb rapidly binds NO• to generate the stable nitrosyl complex HbFeIINO (k=2.6×107 M−1 s−1, in 0.05 M phosphate buffer pH 7.0 and 20 °C [10]) (reaction (1)). OxyHb irreversibly reacts with NO• to produce metHb and nitrate (k=(8.9±0.3)×107 M−1 s−1, in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.0 and 20 °C [11]) (reaction (2)). We have recently shown that, in analogy to the diffusion-controlled reaction between NO• and O2•−, this reaction proceeds via the peroxynitrito-complex HbFeIIIOONO [11,12]. This intermediate was characterized spectroscopically under alkaline conditions [11,12]. At neutral pH HbFeIIIOONO decays very rapidly to metHb and nitrate, and thus does not accumulate in concentrations large enough to be detected [12]. In contrast to free peroxynitrite, the hemoglobin peroxynitrito-complex is not able to nitrate the tyrosine residues of the protein [11]. (The α- and β-subunits of hemoglobin contain three tyrosine residues each.)

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

NO•, unlike O2 and CO, also binds to the oxidized metHb form (kα=1.71×103 M−1 s−1 and kβ=6.4×103 M−1 s−1, in 0.1 M Bistris pH 7.0 and 20 °C [13]). The resulting complex is better described as an iron(II)–NO+ complex, HbFeII(NO+) (reaction (3)). Finally, the oxoiron(IV) form of hemoglobin (ferrylHb), generated under oxidative stress by the reaction of hemoglobin with H2O2, is rapidly reduced by NO• to metHb and nitrite (k=(2.4±0.2)×107 M−1 s−1, in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.0 and 20 °C [14]) (reaction (4)). We have shown that also this reaction proceeds via an intermediate, the O-nitrito complex HbFeIIIONO, which was characterized by transient spectroscopy [14].

3.1 Hemoglobin as an NO•-scavenger

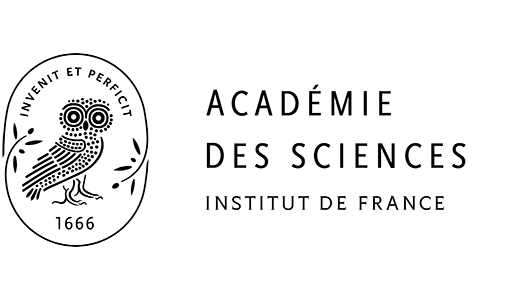

The close proximity of the red blood cells (RBCs) to the site of NO• production and the fast consumption of NO• by oxyHb and deoxyHb observed in vitro [10,11] suggest that most NO• generated by eNOS will be scavenged by the blood. In particular, as the values of the rate constants for the reactions of NO• with oxyHb and with deoxyHb are in the same order of magnitude, one would expect oxyHb, present in about 99% in oxygenated blood, to be the main target for NO•. Under physiological conditions, the reaction between NO• and O2 is too slow [15] to play a significant role. Indeed, the half-life of 100 nM NO• in the presence of about 150 μM O2 (the concentration found in arterial blood) is over two hours (t1/2=1/[8×106 M−2 s−1×100×10−9 M h). In contrast, the half-life of the reaction of 20 mM oxyHb (heme-based concentration present in the RBCs) with physiological amounts of NO• (nM) is less than 1 μs (t1/2=ln2/(8.9×107 M−1 s μs, calculated with the value of the rate constant measured at pH 7.0 and 20 °C [11]). Thus, in principle most NO• should be irreversibly converted to nitrate (Fig. 1). This hypothesis is supported by the strong correlation found, in venous blood of volunteers inhaling 80 ppm NO• for two hours, between the time-dependent increase of the nitrate and the metHb concentrations [16].

Hemoglobin as an NO•-scavenger. NO• produced by eNOS in vascular endothelial cells can diffuse to the adjacent smooth muscle cells where it activates its target enzyme sGC. Excess NO• is scavenged by its rapid reaction with oxyHb, which yields metHb and nitrate.

However, under basal physiological conditions the biological activity of NO• in the blood vessels is not completely lost. A substantial amount of NO• reaches the smooth muscle cells, activates guanylyl cyclase, and thus leads to dilation of the blood vessels. This apparent paradox has prompted to a series of studies aimed to understand the detailed mechanism of the in vivo reaction between circulating hemoglobin and NO•.

3.2 Factors reducing the efficiency of hemoglobin to scavenge NO•

A number of theoretical and experimental studies have been carried out to identify the factors that determine the distance NO• can diffuse from the site of its production in the endothelial cells [17–19]. Lancaster and coworkers showed that the rate of the reaction between NO• and oxyHb is approximately 650 times slower when hemoglobin in encapsulated within the RBCs [20]. This result was explained with the assumption that the limiting step for the reaction of NO• with hemoglobin within the RBCs is the diffusion of NO• from the bulk solution to the RBCs membrane [20]. In contrast, to rationalize similar results Liao and coworkers proposed that it is the membrane that offers the main resistance to NO• diffusion into the RBCs [21]. Nevertheless, a recent study has shown that NO• uptake is primarily limited by extracellular diffusion resistance [22], conceptually represented by an undisturbed layer around the RBCs, where the NO•-concentration is much smaller than the bulk concentration. By taking into account these results, one can explain the significant increase in blood pressure observed when extracellular hemoglobin-based blood substitutes are administered [23]: free hemoglobin, that is Hb not encapsulated within the RBCs, reacts extremely rapidly with NO•, eliminates completely its bioactivity, and thus causes the blood vessels to contract.

A further factor that extends the lifetime of NO• within the blood vessels is a RBCs-free (or RBCs-depleted) region created by intravascular flow close to the vessel wall [24]. This layer reduces the amount of NO• scavenged by the RBCs as it increases the distance NO• has to diffuse to reach them.

3.3 Hemoglobin as an NO•-transporter

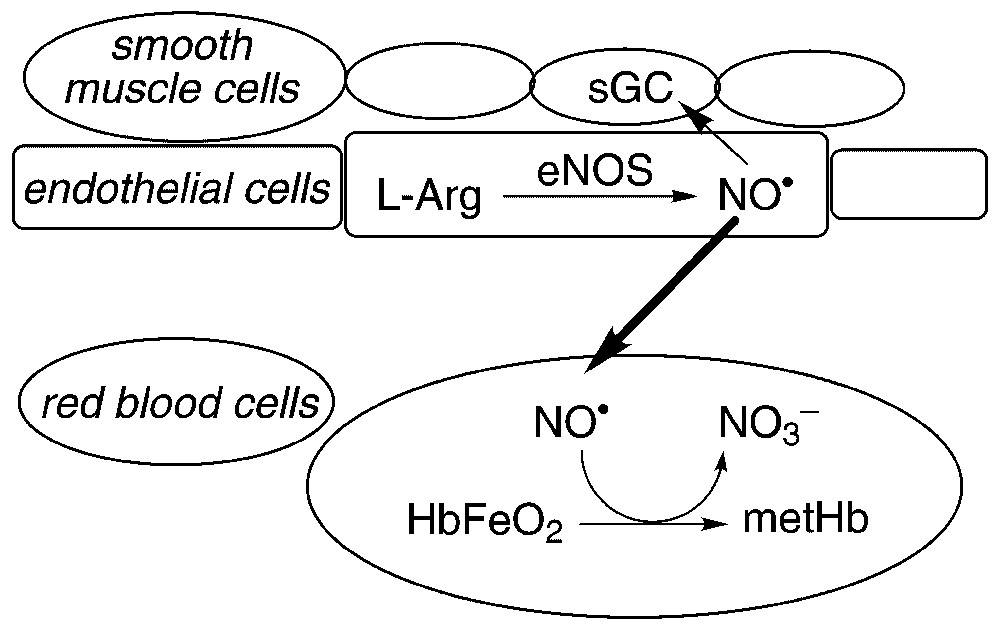

An alternative, conceptually different pathway has recently been proposed to explain how the bioactivity of NO• is maintained within the blood vessels in the presence of high concentrations of hemoglobin (Fig. 2). Stamler and coworkers suggested that, despite the kinetic arguments discussed above, in vivo NO• preferentially binds to the minor fraction of deoxygenated iron centers (about 1%) to yield partially nitrosylated hemoglobin, Hb(FeIINO)(FeO2)3 (reaction (5)) [25]. Difference absorption and EPR spectroscopy were utilized to show that addition of submicromolar concentrations of NO• to oxyHb (in 10 mM phosphate buffer) leads primarily to the generation of nitrosyl Hb [25]. To account for these results, it must be assumed that binding of NO• to partially oxygenated hemoglobin is cooperative. Specifically, NO• should bind R-state Hb(FeII)(FeO2)3 at least 100 times faster than T-state Hb(FeII)4 or Hb(FeII)(FeIINO)3 [26,27].

| (5) |

| (6) |

Hemoglobin as an NO•-transporter. In the arteries (high O2-concentration) NO• binds to Cysβ93 of oxyHb. Deoxygenation of hemoglobin (low O2-concentration) favors liberation of NO•, which reaches sGC, causes blood vessels to dilate, and thus allows for more efficient O2-delivery.

In a subsequent step, the ‘NO group’ has been proposed to be transferred intramolecularly from HbFeIINO to the conserved cysteine residue β93, and to form the so-called S-nitroso-hemoglobin (SNOHb) [28]. It is presumed that this reaction proceeds via oxidation of the iron center by O2 to produce HbFeIIINO ↔ HbFeII(NO+), which can subsequently undergo a formal NO+-transfer to Cysβ93 (reaction (6)) [27,29]. It has been further suggested that, when the RBCs reach O2-depleted tissues, partial deoxygenation of hemoglobin facilitates the release of the ‘NO group’ from SNOHb. A thermodynamic argumentation has been applied to support this reaction step: crystal structures of SNOHb [30] have shown that the S-nitrosocysteine is significantly more stable in oxyHb (R-state), as the S-atom is directed inward and is not exposed to the solvent. Upon dissociation of O2, when the RBCs reach hypoxic tissues, hemoglobin is converted to the T-state (deoxyHb). This transition is coupled with a reorientation of the S-nitrosocysteine toward the solvent. The exposed SNO-group can thus readily undergo transnitrosation reactions with other thiols within the RBCs. Initially, it was proposed that SNOHb reacts with GSH, present in millimolar concentration within the RBCs, to generate GSNO [31]. However, analysis of the S-nitrosated components of the RBCs suggested that SNOHb rather undergoes a transnitrosation reaction with cysteine residues in the Hb-binding cytoplasmic domain of the band-3 anion-exchange membrane protein [32]. Finally, to reestablish the bioactivity of NO•, the ‘NO group’ should be transported out of the RBCs (possibly with the involvement of extracellular GSH [33]), reduced to regenerate NO•, which should diffuse into the smooth muscle cells, bind and activate guanylyl cyclase. The mechanism of these last reaction steps is still unidentified [32,34].

3.4 Arguments against the NO•-transporter hypothesis

One of the central issues of the hypothetical mechanism presented above is that binding of NO• to the heme of partially oxygenated hemoglobin (R-state) is cooperative and depends on the oxygen saturation of hemoglobin. However, Kim-Shapiro and coworkers [35] have recently shown by EPR spectroscopy that, upon mixing of hemoglobin with NO•, there is a linear correlation between the oxygen saturation of hemoglobin and the yield of HbFeIINO. Comparable results were also obtained with blood samples [35]. In another work [36], the same group has reported that the rate constant for NO• binding to R-state hemoglobin, measured by photolyzing HbFeIICO in the presence of NO•, is (2.1±0.1)×107 M−1 s−1. This value is nearly identical to that reported for NO• binding to T-state hemoglobin (2.6×107 M−1 s−1 [10]). Taken together, these results clearly indicate that the rate of NO• binding to hemoglobin is not cooperative and is independent of oxygen saturation.

The pathway suggested for the transfer of the ‘NO group’ from nitrosyl Hb to Cysβ93 (reaction (6)) is also highly unlikely. Reaction of nitrosyl Hb with O2 has been shown to yield metHb and nitrate [37]. The analogous reaction with myoglobin has been proposed to proceed via the intermediate N-peroxynitrito-complex MbFeIII(N(O)OO) (reaction (7)) [38].

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

A further matter of debate is the concentration of SNOHb present in the blood. If NO• was released cooperatively in the capillaries after O2 dissociation, an arterial-venous gradient should exist for the SNOHb-concentration. Indeed, Stamler and coworkers found SNOHb-concentrations of 311±55 nM and 32±14 nM in arterial and venous rat blood, respectively [39]. Nevertheless, Gladwin and coworkers recently developed an accurate and sensitive method to measure very small SNOHb concentrations also in the presence of larger amounts of nitrite and nitrosyl Hb [40]. These authors found that the levels of SNOHb in the basal human circulation, including RBCs membrane fractions, are 46±17 nM in arterial RBCs and 69±11 nM in venous human RBCs [40]. In addition, the same group showed that SNOHb is intrinsically unstable in the reductive environment of the RBCs [40]. This feature further explains the extremely small SNOHb concentrations found in vivo and suggests that SNOHb cannot accumulate in the RBCs to form a reservoir of bioactive NO•.

Finally, the postulated allosterically controlled O2-concentration dependent release of the ‘NO group’ from SNOHb was sustained by kinetic and thermodynamic arguments [41]. However, Patel et al. demonstrated that the rate of the reaction between GSH and SNOHb is rather slow and does not depend on the oxygenation state of hemoglobin [42]. Transnitrosation reactions between thiols in proteins are usually slower than reactions between low molecular weight thiol compounds. Thus, the proposed transnitrosation between SNOHb and the band-3 anion-exchange protein is likely to be too slow to take place within the time taken for a given RBCs to pass through the precapillary vasculature.

3.5 In vitro studies of the reaction between oxyHb and NO•: mixing artefacts

We [43] and others [44,45] have recently shown that, because of the extremely fast reaction between NO• and oxyHb, addition of a small volume of a concentrated NO• solution to a larger volume of a diluted oxyHb solution may lead to artefactual generation of significant amounts of SNOHb. In addition, in agreement with Zhang et al. [46], we observed similar effects for the reaction of NO• with oxyMb in the presence of GSH [43]. These findings imply that some of the high SNOHb yields reported in previous in vitro studies [25,28] may be artefacts arising from the chosen experimental conditions.

To understand the mechanism of this artefactual S-nitrosation of hemoglobin, one has to consider the half-life of the reactions that could take place in the system before the concentrations of all reagents have reached homogeneity. When a saturated (2 mM) NO• solution is mixed with a 50-μM oxyHb solution, at the interface of the two solutions, the half-life of the reaction is so short (t1/2=ln2/(8.9×107 M−1 s μs) that metHb is generated before NO• has reached a uniform concentration in the reaction mixture. Thus, NO• could also react with metHb and produce the nitrosating species HbFeII(NO+) (t1/2(β)=ln2/(6.4×103 M−1 s ms and t1/2(α)=ln2/(1.7×103 M−1 s ms). Finally, before NO• will be dispersed in the solution, the reaction of NO• (2 mM) with O2 (in the air saturated oxyHb solution, 220 μM) [15] could also occur ( s−1×2×10−3 M ms). The reaction of NO• with O2 in aqueous solution is believed to proceed via the formation of NO2 and N2O3 [15]. Taken together, these simple calculations suggest that upon reaction of NO• with oxyHb nitrosating species such as NO2, N2O3, and HbFeII(NO+) can be generated in high local concentrations and thus lead to artefactual production of SNOHb.

To get a better understanding of these mixing effects, we have recently carried out a systematic study of the influence of different factors on the amount of SNOHb produced from the reaction of NO• with oxyHb [43]. Our results showed that the relative SNOHb yields (expressed relative to the amount of NO• added) increase with decreasing amounts of NO• added. Moreover, when the NO• solution is added very slowly (within 1–2 min) from a diluted solution (equivalent volumes of the NO• and the oxyHb solutions) the SNOHb yields are larger than those obtained by adding a very small volume of a 2 mM NO• solution (at identical final NO•- and oxyHb-concentrations). Interestingly, Han et al. [44] found that when NO•-donors were employed to slowly deliver small concentrations of NO•, oxyHb was converted exclusively to metHb and nitrate, without formation of detectable amounts of SNOHb. In contrast, Joshi et al. [45] reported that the SNOHb yields were nearly identical when NO• was added as a bolus or with an NO•-donor. These contrasting results may arise from the different NO•-donors used by the two groups (DEA [44] vs. MHMA [45]), and thus suggest that NO•-donors are not always good substitutes for NO•.

3.6 Possible pathways for in vitro SNOHb production

As mentioned above, N2O3 may be one of the possible species responsible for SNOHb generation upon mixing of NO• with oxyHb (reaction (11)). This hypothesis is supported by our observation that, in some cases (by slow addition of diluted NO• solutions), the SNOHb yields are slightly lower when the reaction is carried out in more concentrated phosphate buffer (0.1 M vs. 10 mM) [43]. The decrease of the SNOHb production is due to the concurrent hydrolysis of N2O3 (reaction (12)), which has been shown to be catalyzed by inorganic phosphates [47].

| (11) |

| (12) |

To evaluate the nitrosating efficiency of the iron(III) nitrosyl heme complex, we studied the reactions of NO• with metHb and with a mixture of metMb/GSH [43]. We found that the amount of SNOHb formed from the reaction of NO• with metHb is larger than the GSNO yields obtained under identical conditions from the reaction with metMb/GSH [43]. Systematic studies indicated that maximal relative SNOHb yields (expressed relative to the amount of NO• added) are generated when substoichiometric amounts of NO• are added to metHb. Under these conditions a larger fraction of NO• is bound to the β-subunit of hemoglobin [13,29] and may lead to higher SNOHb yields via an intramolecular nitrosation of Cysβ93. In fact, this residue is located on the proximal side of the heme, at a distance of only ∼10 Å from the iron center [30]. Studies with myoglobin have shown that photolyzed heme ligands can diffuse to the proximal side and partly occupy a hydrophobic pocket close to Cysβ93 in hemoglobin [48,49]. Thus, HbFeII(NO+) may react with H2O, generate H2NO2+ or HNO2, which may rapidly diffuse to the proximal side of the heme, and react with Cysβ93. This intramolecular pathway, possibly facilitated by the hydrophobic environment of Cysβ93, may explain why this residue is nitrosated more effectively than GSH.

Finally, we have recently proposed that an additional pathway may be responsible for SNOHb formation. Specifically, we found that addition of 1 or 0.1 equiv of NO• to the heme-blocked metHbCN (under strictly anaerobic conditions), followed by degassing of the reaction mixture, and subsequent exposure to air, led to the generation of SNOHb (0.9±0.2% and 4.0±0.3% relative to the amount of NO• added, respectively) [43]. It has recently been shown that NO• can also occupy non-covalent binding sites in hemoglobin, possibly trapped by aromatic amino acid residues in hydrophobic pockets [50]. As discussed above, the environment of Cysβ93 is largely hydrophobic. Moreover, two aromatic amino acids, Tyrβ145 and Pheβ103, are located at a distance of 4–5 Å from the sulfur atom of Cysβ93. Because of its lipophilic nature, NO• preferentially partitions into lipid membranes and hydrophobic protein environments [51]. Taken together, these observations suggest that high local amounts of NO• and O2 could be trapped close to Cysβ93 and may therefore lead to their efficient nitrosation.

4 Conclusions

The mechanism of the reaction between circulating hemoglobin and NO• is currently a matter of debate. In this short review, I have presented the current status of the research on this area. The rapid reaction between NO• and oxyHb is likely to represent an important scavenging pathway for the excess NO• generated by eNOS in the blood vessels (Fig. 1). Indeed, it has been shown that the amount of NO• released by eNOS is approximately 400 nM [52], whereas only 45 nM (EC50) are needed to activate sGC in cells [53]. The hypothesis that besides O2 and CO2 hemoglobin transports NO• is highly controversial. According to this theory, NO• binds to Cysβ93 of oxyHb, is liberated after deoxygenation of hemoglobin, and consequently allows for a more effective delivery of O2 to peripheral tissues (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, an increasing amount of data collected by different groups and summarized here, challenge most steps of this hypothetical mechanism. The major obstacle for the study of the mechanism of the reaction between hemoglobin and NO• is probably represented by the artefactual production of SNOHb when the reaction is carried out in vitro. This problem is due to the very fast rate of this reaction and makes it impossible to draw conclusions on the in vivo mechanism from studies with purified oxyHb.