Version française abrégée

A. pelagicum Arcangeli, 1955 est un crustacé isopode terrestre, endémique aux ı̂les circum-siciliennes et à la Tunisie septentrionale. Dans ce présent travail, le cycle de vie et la structure de population de cet Oniscoı̈de ont été étudiés à partir d'un échantillonnage mensuel ou bimensuel réalisé durant 16 mois, de janvier 2000 à avril 2001. La population naturelle étudiée est celle de l'Aouina, localisée aux environs de Tunis (36°51′N). Le suivi du pourcentage des femelles ovigères met en évidence le fait que cette population présente une reproduction saisonnière de mars/avril jusqu'à la fin du mois d'août, suivie par une phase de repos sexuel de septembre à février/mars. Pendant la saison de reproduction, les pourcentages de femelles ovigères sont plus élevés au printemps (42,2 à 97,4 %) qu'en été (<42 %). Le recrutement des jeunes pulli a lieu d'avril/mai à la mi-septembre.

La fécondité, estimée par le nombre d'œufs contenus dans le marsupium montre une variabilité intrapopulationnelle. En effet, ce nombre varie entre 15 et 82 œufs, avec une moyenne de 50,91±14,3. Par ailleurs, cette fécondité est positivement corrélée avec la masse des femelles (r=0,7, ddl=52). Le sex ratio, estimé d'après le rapport du nombre des mâles sur celui des femelles, subit des fluctuations durant la période d'échantillonnage (0,25 à 1,33) ; il est, le plus souvent, en faveur des femelles.

L'analyse des histogrammes de fréquence du logarithme de masse a permis d'identifier la présence de neuf cohortes, dont trois détectées dans le premier échantillon de janvier 2000 et les six autres durant le reste de la période d'échantillonnage. Le suivi de l'accroissement de la masse moyenne des cohortes C6 et C7+C8 depuis leur recrutement montre des taux d'accroissement plus élevés pendant les premiers stades de vie et au printemps. En revanche, en hiver, ce taux subit plutôt un décroissement. En tenant compte de l'évolution des taux d'accroissement et du cycle de vie de chaque cohorte, la longévité estimée est de 6 à 13 mois. De plus, les cohortes, nées au printemps et au début de l'été, ont une longévité courte (6 mois), une maturité sexuelle précoce (3 mois) et une seule portée. En revanche, les cohortes nées à la fin de l'été et au début de l'automne ont une durée de vie plus longue (12–13 mois), une maturité sexuelle plus tardive (7–9 mois) et un nombre plus élevé de portées (3 à 5 portées). Les caractéristiques du cycle de vie de l'espèce A. pelagicum de l'Aouina se résument ainsi : (i) espèce semi-annuelle (les femelles produisent jusqu'à cinq portées par an), (ii) femelles itéropares (les femelles se reproduisent plusieurs fois durant leur vie), (iii) espèce bivoltine (la population produit deux générations par an), (iiii) longévité variable des cohortes en fonction des saisons.

1 Introduction

The biology and the reproductive pattern were studied in several species of Oniscidea from arid, tropical and temperate regions. Most of these species have a seasonal breeding pattern such as Porcellio dilatatus Brandt, 1833 [1], Armadillidium vulgare (Latreille, 1804) [2,3], Porcellio laevis (Latreille, 1804) [4], Armadillo officinalis (Dumeril, 1816) [5,7], Hemilepistus reaumuri (Audouin, 1826) [5,8,9], Porcellio ficulneus Verhoeff [6,10], Porcellio scaber Latreille, 1804 [11], Porcellio variabilis (Lucas, 1846) [12,13], Porcellionides pruinosus Brandt, 1833 [14] and Porcellionides sexfasciatus Budde-Lund, (1879) [15]. Nevertheless, some rare Oniscids species exhibited a continuous breeding pattern. It is the case of Porcellionides pruinosus in tropical and temperate habitats [16].

In the genus Armadillidium, A. vulgare is the only species carefully studied, particularly its breeding activity and population biology. This cosmopolitan species exhibits a high intra and interpopulational variability in its reproductive patterns [3,17,18]. According to [3], the success of A. vulgare in colonizing all parts of the world is due to its reproductive tactics flexibility.

In this present paper, we set out to study the life cycle and the population structure of Armadillidium pelagicum Arcangeli, 1955, endemic to circum-Sicilian islands and Tunisia [19]. The aim is to study (1) the reproductive cycle, (2) the population structure, (3) the fecundity, and (4) the sex ratio of a Tunisian population occurring at Aouina.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study site and sampling

The sampling station is located at Aouina, in the North-East of Tunisia, 5 km from Tunis, at an altitude of 3 m. The climate is semi arid, characterized by a hot dry season from May to September, a moderately cold autumn during October and November, a cold rainy winter during December and January and a pleasant spring during March and April. This site, humid, except during summer and in the early autumn, was a garigue dominated by Ferula communis and Asphodellus microcarpus. Nowadays, a road is in place of this sampling site.

Specimens of A. pelagicum were found beneath stones, decaying leaves, in detritus and in the compost. They were collected once a month during most of the year and twice a month during the breeding season.

2.2 Laboratory procedures

In the laboratory, specimens were counted, weighed using a Mettler AB204-S balance (±0.1 mg accuracy) and sexed. The sex determination was based on the presence or absence of oestegites or a broodpouch in females and of genital apophyse and developed endopodite at the pleopod I and II in males.

In adult males, the endopodite of pleopod I is more differentiated and the pereiopod VII shows a brush of setose at the carpus and the merus. In juvenile males, the endopodites of pleopod I and pleopod II are not much differentiated.

The females are also divided into two groups:

- – nonreproductive females grouping juveniles and adults without marsupium;

- – reproductive females showing a brood pouch full of eggs or embryos (ovigerous females) or an empty marsupium (nonovigerous females).

In immature specimens, the weight does not exceed 3.9 mg.

Table 1 summarizes the size of the different population categories and the sex ratio at the sampling dates.

Number of the different categories of individuals recorded for each sampling. Nt: Total number of individuals; Ni: number of immatures; Njm: number of juvenile males; Nmm: number of mature males; Nnrf: number of non-reproductive females; Nof: number of ovigerous females; Nnof: number of non-ovigerous females

| Sampling dates | N t | N i | N jm | N mm | N nrf | N nof | N of | Sex ratio |

| 16/01/2000 | 99 | 0 | 26 | 12 | 61 | 0 | 0 | 0.62∗ |

| 16/02/2000 | 108 | 0 | 11 | 45 | 52 | 0 | 0 | 1.07 |

| 17/03/2000 | 103 | 0 | 1 | 40 | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0.66∗ |

| 02/04/2000 | 70 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 26 | 0 | 19 | 0.55∗∗ |

| 16/04/2000 | 102 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 2 | 0 | 75 | 0.32∗∗ |

| 3/05/2000 | 84 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 24 | 35 | 0.42∗∗ |

| 21/05/2000 | 113 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 2 | 27 | 51 | 0.41∗∗ |

| 04/06/2000 | 106 | 18 | 1 | 34 | 0 | 13 | 40 | 0.66∗ |

| 18/06/2000 | 89 | 13 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 40 | 4 | 0.73 |

| 08/07/2000 | 138 | 43 | 1 | 37 | 2 | 34 | 21 | 0.67∗ |

| 06/08/2000 | 53 | 1 | 1 | 26 | 2 | 13 | 10 | 1.08 |

| 20/08/2000 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 5 | 17 | 13 | 0.4∗∗ |

| 12/09/2000 | 30 | 9 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 1.33 |

| 9/10/2000 | 72 | 0 | 34 | 0 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0.89 |

| 12/11/2000 | 108 | 0 | 8 | 45 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 0.96 |

| 24/12/2000 | 116 | 0 | 1 | 49 | 66 | 0 | 0 | 0.76 |

| 21/01/2000 | 95 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0.6∗ |

| 18/02/2000 | 124 | 0 | 0 | 41 | 80 | 1 | 2 | 0.49∗∗ |

| 23/03/2000 | 124 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 1 | 0 | 98 | 0.25∗∗ |

| 15/04/2000 | 110 | 40 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 9 | 39 | 0.46∗∗ |

∗ Significant difference (5%).

∗∗ Highly significant difference (1%).

2.3 Statistical analysis

Data in milligrammes were converted into logarithmic unity (UL). The identification of cohorts along mass frequency distribution at successive sample dates was carried out using the probability paper method [20] as performed by Cassie [21,22]. Both χ2 and G tests (P⩾0.05) were used to test reliability [23,24]. Computations were done using Anamod Software [25].

Fecundity, which is the number of eggs in the marsupium, was estimated for 54 ovigerous females. Eggs in the first stage of their development were emptied from the marsupium in a Petri dish containing 70% alcohol and then counted.

The sex ratio was estimated by the ratio of males to females. The observed and expected values were compared using a χ2 test.

3 Results

3.1 Population structure

According to data (Fig. 1), immature specimens appeared in the population during the year 2000 from the beginning of June to July and in mid-September. In 2001, they appeared starting in April. Except in October 2000, mature males (Fig. 1) were present in the population and their percentages fluctuated between 7 and 49.05%. Moreover, two main peaks were present respectively at the beginning of August (49.05%) and at the end of December (42.24%). During the sampling period, the percentage of juvenile males was low, except in January and October 2000, when it reached 26 and 47.2%, respectively. The youngest juvenile male weighted 3.9 mg.

Structure of the population (sampling dates are indicated in Table 1).

Otherwise, the survey of the percentage of ovigerous females during the year 2000 showed that the breeding period started at the beginning of April and ended in August. Moreover, the percentages of gravid females are more important in spring than in summer, indicating two distinct breeding periods:

- – a spring breeding period, from the beginning of April to the beginning of June, where the percentage of ovigerous females varied from 42.22 to 97.4%;

- – a summer breeding period, less extended, occurred from the beginning of July to the end of August; throughout this period, the percentage of ovigerous females did not exceed 42%.

In 2001, ovigerous females appeared in the population from March.

The fecundity, estimated by the number of eggs produced by broods, showed up intrapopulation variability. The number of eggs varied from 15 to 82, with an average of 50.91±14.3. A relationship seems to exist between fecundity and the mass of ovigerous females. In fact, the lowest value (15) characterized a female of 47.5 mg, while the highest one (82) characterized a female of 68.2 mg. Moreover, a significant positive correlation (r=0.7, ddl=52) was found between these two parameters.

The sex ratio (Table 1) underwent fluctuations throughout the sampling period (0.25 to 1.33), remaining, however, in favour of females. It deviated significantly from the expected values in January, March, April, May, early June, July, the end of August 2000 and January, March, April 2001.

3.2 Growth and life cycle

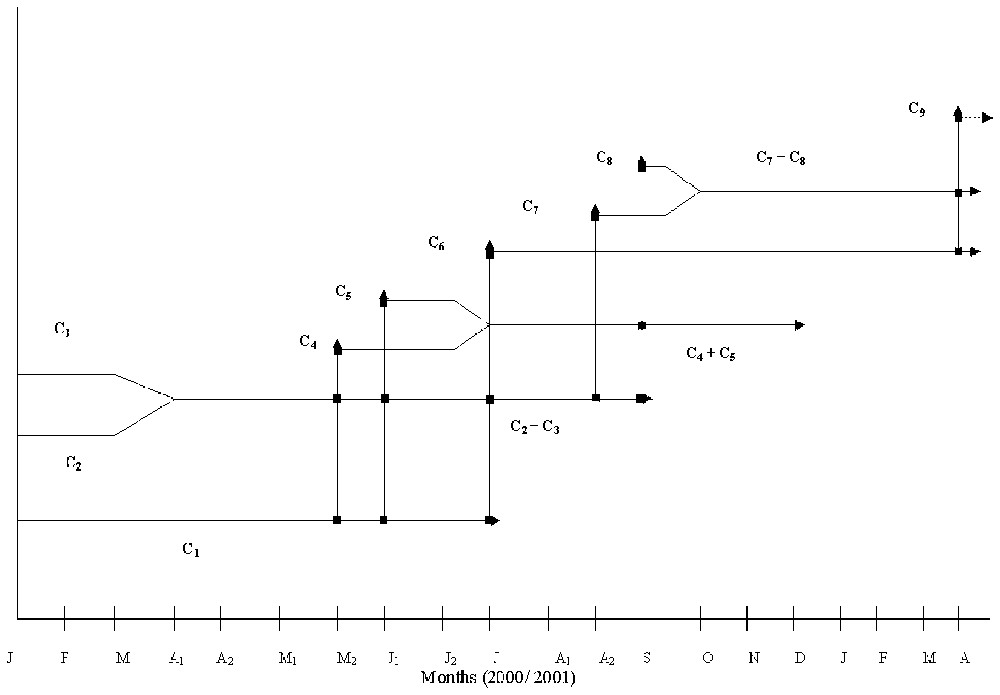

Mass-frequency polymodal distributions were analysed for recognizable cohorts (Fig. 2). Three cohorts (C1, C2, and C3) could be identified from the first sampling date in January 2000. Cohorts 4 and 5 were recognized on 4 June 2000, cohort 6 on 8 July 2000, cohorts 7 and 8 on 12 September 2000 and finally cohort 9 on 15 April 2001. According to their masses, cohorts 4 and 7, identified in June and in the mid-September respectively, did not consist of newly born individuals and therefore the recruitment must have taken place previously, in May for cohort 4 and in August for cohort 7.

Mass-frequency distribution of A. pelagicum at Aouina. UL: logarithmic unity (logarithmic class=0.1 UL).

The biggest female recorded has a mass of 208.2 mg and the smallest one weighs 4 mg, while the largest male weighs 119.9 mg and the smallest one only 3.9 mg.

Field growth rates were estimated from the mean size of recognizable cohorts. The survey of field growth rates of cohorts C6 and C7+C8 (Fig. 3), showed high rates in early phases, decrease during winter and increase during spring.

Growth of cohorts or groups of cohorts (mean mass (mg) standard deviation).

Otherwise, the mass-frequency analysis allowed us to determine the cohorts to which males and ovigerous females belonged, and to determine their contribution to recruitment (Fig. 4). Females of cohort 1 started their breeding period at the beginning of April 2000, giving birth to cohorts 4, 5, and 6. They disappeared at the beginning of August 2000. Cohorts 2 and 3, identified from January 2000, merged at the beginning of April and gave birth to cohorts 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 and disappeared in October (9 October 2000). Cohorts 4 and 5 merged at the beginning of July 2000, giving birth only to cohort 8 and disappeared in January 2001. Cohort 9 born in March 2001 was issued from mating in cohorts C6 and C7+C8.

The life cycle of A. pelagicum at Aouina.

According to the field growth rate and the life cycle of each cohort, the life span was estimated at 6 to 13 months. Thus, cohorts (C4, C5) born at the end of spring and in early summer (May–June) had a shorter life span (6–7 months) than those (C6, C7, C8) born in the summer and early autumn (12 to 13 months).

Hence, the life cycle characteristics of A. pelagicum at Aouina may be summarized as follows: (a) semi-annual species, since females appear to produce up to five broods per year (C2+C3), (b) iteroparous females, since females seem to reproduce twice or more in their life time; (c) bivoltine life cycle, since the population produces two generations per year; (d) variable life span, since the cohorts born in autumn live more than those born in spring.

4 Discussion

Despite its limited geographical distribution, A. pelagicum exhibits the same reproductive patterns as the majority of the terrestrial isopods species. In fact, the survey of the breeding cycle of this species at Aouina, over a period of 16 months (from January 2000 to April 2001), showed a seasonal reproduction extending from March/April to the end of August followed by a sexual rest from September to February/March. The recruitment period of this population was spread from April/May to mid-September. Most species of terrestrial Isopods exhibited a seasonal reproduction with more or less variations in the onset and duration of this reproduction. Willows (in [28]) suggested in 1984 that “this kind of reproduction is actually a response to favourable conditions for rapid development and offspring release.” In Tunisia, the terrestrial Isopods Porcellio variabilis [12,13], Porcellionides pruinosus [14] and Porcellionides sexfasciatus [15] have a more extended reproductive period than A. pelagicum at Aouina. This could be explained by the more important tolerance of these former species to harsh xeric conditions allowing them to colonize even the southern part of Tunisia. Nevertheless, some Tunisian populations of the xeric species Hemilepistus reaumuri exhibit a short reproductive period from mid-May to July [9], probably related to the social behaviour of this species, particularly the nurturing of their offspring. Otherwise, A. pelagicum has nearly the same reproduction period as several populations of Armadillidium vulgare native from low latitude localities in California [26] and France [27], and a more extended reproductive period than several English populations [3].

The survey of the size distribution structure during the period of study showed the presence of 9 cohorts. The cohorts, born at the end of spring (C4) and early summer (C5), have a short life span (6 months), a precocious sexual maturity (3 months) and a small number of broods (1 brood). Whereas, cohorts born in summer (C6, C7) and early autumn (C8), have a long life span (12–13 months), a late sexual maturity (7–9 months) and a great number of broods (3 to 5). Compared to A. vulgare, A. pelagicum at Aouina exhibited some specific features in its life history traits such as a shorter life span (6–13 months) than several populations of A. vulgare (35–41 months) [3], an earlier sexual maturity (3–9 months) than A. vulgare (12 to 25 months) [3]. The different life-history traits between these two species could be explained by their different growth rates, because of their same mean masses at reproduction, estimated at 28 mg in A. vulgare in California [3] and at 29.36±8.01 mg in A. pelagicum. These results suggest that mass or size has greater influence on sexual maturity than age, and confirm those of [3] on several woodlice species. Growth rates are high in early phase, decrease in winter and increase in early spring.

The sex ratio is almost always favourable to females (62% females and 38% males). Except for some cases, females usually outnumbered males in terrestrial Isopods [4,7,14,29]. In Porcellionides pruinosus, the biased sex ratio favouring females is due to an intracytoplasmic Wolbachia bacterium, which reverses genetic males (ZZ) into functional neo-females (ZZ+F) [30]. Two feminizing sex ratio distorters are known in the woodlice A. vulgare: the intracytoplasmic Wolbachia bacterium [31] and an unidentified non-Mendelian genetic element labelled f [32].

A. pelagicum exhibited a great intrapopulation variability of fecundity (15 to 82 eggs) as well as a positive relationship between the number of eggs and ovigerous females mass. This positive correlation is reported for some terrestrial Isopods, A. vulgare [26], Porcellio laevis [4], Armadillo officinalis [7], Porcellio scaber [11], Porcellionides pruinosus [14], and Porcellionides sexfasciatus [15]. Therefore, large females produce larger broods than small females, hence birth rate in populations is not only related to the number of reproductive females, but also to their size at reproduction [33]. The mean number of eggs in ovigerous females marsupium of A. pelagicum is 51.14±14.00. A similar number was reported (50 eggs) in Porcellio scaber [11]. Small values were observed in Porcellionides pruinosus (18±3.4) [14], Armadillo officinalis (25 eggs) [7], Armadillo albomarginatus (9.9 eggs) and Armadillo sp. (27 eggs) [5]. However, high values were found in Porcellio obsellatus ficulneus (76.9 eggs) [5], Hemilepistus reaumuri from the Negev (103 eggs) and from Tunisia (77) [6]. The average number of eggs per broodpouch in various woodlice depends upon the species and locality [34]. The range of observed fecundity is best explained by a combination of factors that influence the growth of individuals, namely the genetic determinants of the growth exponent, the ability of the individual to accrue resources, the environmental conditions, the birth date in seasonal environments, the timing of allocation of resources to reproduction, and the timing within a temporal sequence of reproductive events in iteroparous species [28].