1 Introduction

The microbial degradation of hydrocarbons is of environmental and biotechnological interests. The anaerobic biodegradation of hydrocarbons has been demonstrated under nitrate-reducing, sulphate-reducing and methanogenic conditions [1]. Sulphate- or nitrate-reducing bacterial strains, able to oxidize hydrocarbons under strictly anoxic conditions, have been isolated [1]. To date, among the sulphate-reducing isolates, only five strains are able to oxidize aliphatic hydrocarbons [2–6]. These strains are known to degrade alkanes and most of them also oxidize alkenes. Recently, it has been demonstrated that, contrary to a previous hypothesis, initial n-alkane activation under sulphate-reducing conditions does not occur via dehydrogenation in the corresponding n-alkene [4], but rather proceeds by addition of fumarate [7] or by carboxylation reactions [8].

Limited information is presently available concerning the degradation of n-alkenes by sulphate-reducing bacteria. Therefore, we investigated the anaerobic degradation of C-odd and C-even n-alkenes by a sulphate-reducing bacterium, Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T, recently isolated from polluted sediments and able to oxidize n-alkenes to carbon dioxide [6].

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Source of organism and culture conditions

The sulphate-reducing bacterium Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T was isolated from polluted marine sediments (Gulf of Fos, France) [6]. It was grown on anoxic sulphate-reducing medium containing (l−1 distilled water): Na2SO4, 3 g; KH2PO4, 0.2 g; NH4Cl, 0.3 g; NaCl, 24 g; MgCl2·6 H2O, 4.46 g; KCl, 0.5 g; CaCl2·2 H2O, 0.15 g; NaHCO3, 2 g; Na2S·9 H2O, 0.3 g; vitamin V7 solution [9], 1 ml; trace-element solution SL12 [10], 1 ml; selenite–tungstate solution [11], 1 ml; pH 7.5. The medium was prepared under a gas mixture (N2/CO2, 90:10) according to the method of Pfennig et al. [9]. Cultures were carried out as previously described [6] with sodium octanoate (2 mM) or 1-tetradecene (1.4 mM) as organic substrate. In some experiments with hydrocarbon, α-cyclodextrin (5 g l−1) was added to the medium from a sterile stock solution (10%). Growth on organic substrates was followed by measuring sulphide production [12].

2.2 Action of antibiotics on growth and sulphate respiration

Growth inhibition tests were performed in the presence of chloramphenicol, streptomycine or tetracycline (100 μg ml−1) in cultures grown with sodium octanoate (2 mM). Growth was monitored by OD450 nm with a Spectronic model 20D+ spectrophotometer (Milton Roy). Sulphate respiration was monitored by measuring sulphide production.

2.3 Substrate degradation in dense cell suspensions

Cells of Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T were grown in a 600-ml culture with sodium octanoate as substrate. After 5 days of incubation, the culture (OD450 nm=0.2) was centrifuged (5000 g for 15 min at 4 °C) and cells were washed twice with N-free sulphate-reducing medium [6]. The cell pellet was suspended in 60 ml of N-free medium and sub-fractions (3.5 ml) were distributed under a gas mixture (N2/CO2, 90:10) into 5-ml bottles and were supplemented with sodium dithionite (0.12 mM) as additional reductant. Sodium octanoate (2 mM) or 1-tetradecene (1.4 mM) and α-cyclodextrin (5 g l−1) were added to the cell suspensions. Controls without substrate were performed. Tetracycline (1 mg ml−1) was added from a stock solution (0.5% w/v) into some of these bottles. All assays and controls were carried out in duplicate. Substrate degradation was followed indirectly by measuring sulphide production.

2.4 Analysis of total cellular fatty acids

Cultures (500 ml) of Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T grown on 1-pentadecene (1.3 mM), 1-hexadecene (1.25 mM) or organic acids (sodium octanoate or sodium nonanoate, 2 mM) were analysed after 3 months of incubation at 30 °C. Cells were collected by filtering the culture through a glass microfibre filter (GF/B, Whatman). Filters were saponified with 1 N KOH in CH3OH/H2O (1:1, v/v, reflux 2 h). After extraction of the neutral lipids from the basic solution (n-hexane, 3×30 ml), acids were extracted using dichloromethane (3×30 ml) following the addition of 2 N HCl (pH=1). The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4, concentrated by rotary evaporation and then evaporated to dryness under nitrogen. Fatty acids were silylated by reaction with bis-trimethylsilyl-trifluoroacetanamide (BSTFA, [13]). Pyrrolidide derivatives were prepared from fatty-acid methyl esters, as described by Christie [14].

Fatty acids were identified with a HP5890 series II plus gas chromatograph connected to a HP5972 mass spectrometer as previously described [13]. The gas chromatograph was equipped with a fused silica capillary column (30 m×0.25 mm i.d.) coated with Solgel-1 (SGE; film thickness =0.25 μm). Assignment of the double-bond position in monounsaturated fatty acids was based on stereospecific oxidation with OsO4 and subsequent trimethylsilylation [15]. Catalytic hydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids was performed in ethyl acetate with PtO2 as a catalyst.

2.5 Nomenclature of fatty acids

The nomenclature of fatty acids recommended by the IUPAC-IUB [16] was adopted in this study. An n-saturated octadecanoic acid is designated as 18:0, with the first number representing the number of carbon atoms on the acyl group and the second number representing the number of double bonds present. A branched fatty acid, such as 4-methyloctadecanoic acid, is designated as 4-Me-18:0 and a monounsaturated branched fatty acid, such as 4-methyl-octadecen-11-oic acid, is designated by 4-Me-18:1Δ11. i- and a- refer to iso- and anteiso-branched fatty acids respectively.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Growth of Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T on n-alkene

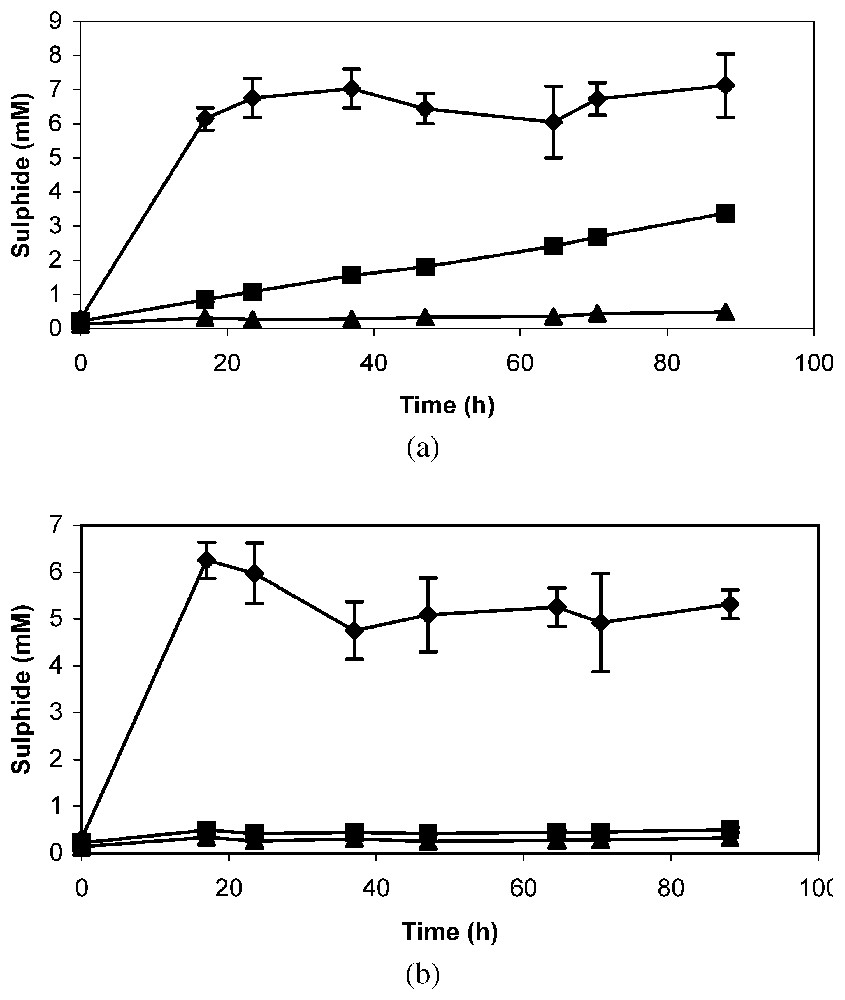

Growth of Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T with n-alkene as substrate was slow (Fig. 1). Addition of α-cyclodextrin, a potential carrier of hydrophobic compounds, significantly stimulated the growth, without being used as a substrate for growth. α-Cyclodextrin exhibits hydrophobic cavities and can form inclusion complexes with water-insoluble molecules, like hydrocarbons. Thus, these later are dispersed in water solution and become more accessible to bacteria. Aeckersberg et al. [4] have already observed that growth of strain Hxd3, a hydrocarbon-degrading sulphate-reducing bacterium, was stimulated by addition of α-cyclodextrin.

Influence of α-cyclodextrin on sulphide production during growth of Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T on 1-tetradecene (▴), α-cyclodextrin (•) and a mixture of 1-tetradecene and α-cyclodextrin (■). Mean value of triplicate cultures ± standard deviation.

In order to verify if alkene oxidation by strain CV2803T requires inducible enzyme synthesis, experiments were performed in dense cell suspensions with and without antibiotics. A previous experiment was performed to test the action of three selected antibiotics (potential inhibitors of protein synthesis) on growth and sulphate-reducing activity of strain CV2803T. Among the antibiotics tested, tetracycline and chloramphenicol inhibited growth of Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T (Fig. 2), whereas its sulphate-reducing activity was exclusively inhibited by chloramphenicol (Fig. 3). Tetracycline was thus chosen to perform experiments in dense cell suspensions. These latter were obtained from a culture grown on sodium octanoate.

Growth of Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T on sodium octanoate in absence (♦) and in presence of different antibiotics (100 μg ml−1): chloramphenicol (▴), streptomycine (×) and tetracycline (•). Controls were performed without substrate or antibiotic (■). Mean value of triplicate cultures ± standard deviation.

Sulphide production by Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T grown on sodium octanoate with tetracycline, chloramphenicol and without antibiotic (control) after five days of incubation.

In the absence of antibiotic, a strong production of sulphide was observed during the first hours when cell suspensions were incubated with sodium octanoate (Fig. 4a). With n-alkene, a gradual increase in sulphide concentration was observed throughout the 90 hours of incubation, whereas, in the absence of substrate, no sulphide was produced (Fig. 4a). The addition of tetracycline did not modify the production of sulphide in assays with sodium octanoate, but did inhibit it in the presence of n-alkene (Fig. 4b). These results suggest that the enzymes required for n-alkene oxidation by Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T were not synthesized during growth on organic acid and that they are inducible.

Sulphide production in dense cell suspensions of Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T incubated with sodium octanoate (♦), 1-tetradecene (■) and without substrate (▴), in the absence (a) or in the presence (b) of tetracycline (100 μg ml−1). Mean value of duplicate suspensions ± standard deviation.

3.2 Fatty acids composition of Desulfatibacillum aliphativorans strain CV2803T

The determination of the fatty-acid composition of hydrocarbonoclastic microorganisms can be of interest for metabolic pathway studies [4], as well as for the identification of specific markers of bacterial activities. For instance, Doumenq et al. [17] suggested that the fatty-acid composition of marine sediments exposed to petroleum hydrocarbons can reveal the presence of hydrocarbonoclastic bacterial communities and can be used to define bioremediation indexes.

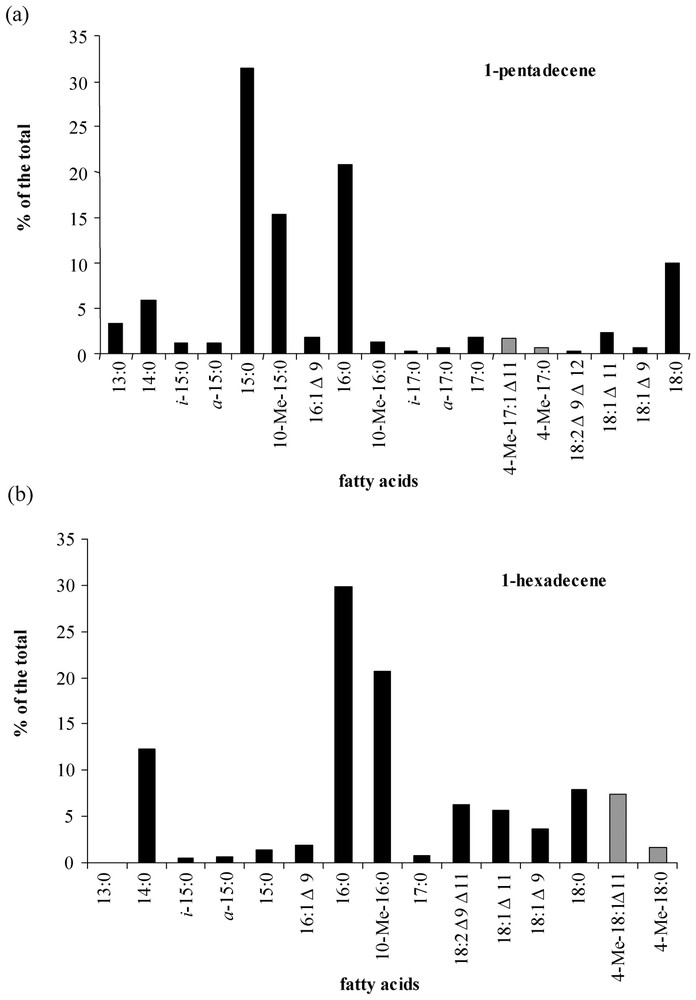

Cellular fatty acids of strain CV2803T grown on 1-pentadecene were predominantly C-odd (Fig. 5a), whereas C-even fatty acids predominated when 1-hexadecene was used as growth substrate (Fig. 5b). Similar fatty-acid distributions were observed during growth on C-odd (sodium nonanoate) and C-even (sodium octanoate) fatty acids (results not shown). Thus, the chain length of growth substrates influenced the overall cellular fatty-acid composition of strain CV2803T, as already observed in other hydrocarbon-degrading sulphate-reducing bacteria [4,18]. In addition to linear saturated fatty acids, cultures on n-alkenes produced branched (iso-, anteiso- and 10-Me-) and unsaturated (e.g., 18:1Δ11 and 18:1Δ9) fatty acids commonly encountered in bacteria [19–22].

Relative abundance of the total cellular fatty acids of Desulfatibacillum aliphaticivorans strain CV2803T grown on 1-pentadecene (a) and 1-hexadecene (b). Unusual unsaturated branched fatty acids that could constitute potential markers of n-alkene transformation by sulphate-reducing bacteria are represented by grey bars.

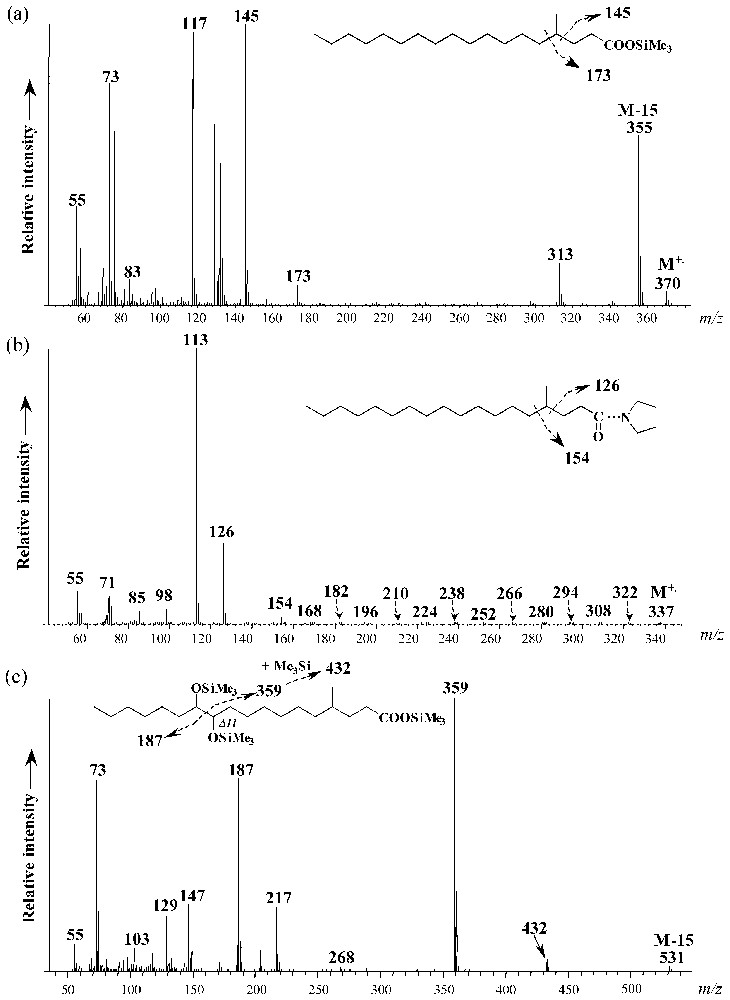

Cultures of strain CV2803T on 1-pentadecene and 1-hexadecene also yielded to saturated and monounsaturated methyl-branched hepta- and octadecanoic acids, respectively (Fig. 5). These compounds were not detected in cultures grown on fatty acids (data not shown). Specific ions due to the α cleavage of the branched carbon atom in the mass spectra of the saturated compounds allowed their identification as 4-Me-17:0 and 4-Me-18:0 fatty acids, respectively (Fig. 6a). The position of the methyl branch in these compounds was further confirmed by the analysis of their pyrrolidide derivatives (Fig. 6b). Upon catalytic hydrogenation, Me-17:1 and Me-18:1 fatty acids were converted to 4-Me-branched fatty acids indicating that the methyl branch in the above-defined saturated and monounsaturated methyl-branched fatty acids was located on the same carbon atom (C-4). The location of the double bonds in 4-Me-17:1 and 4-Me-18:1 fatty acids was achieved by derivatization. The applied stereospecific oxidation of unsaturated fatty acid with OsO4 yields to the corresponding vicinal dihydroxy derivative which after trimethylsilylation is well suited for mass-spectrometric determination of the original double-bond position [15]. The α-cleavage product ions of the vicinal bis(trimethylsilyl)-ether derivatives (at m/z 187, 359 and 432 for 4-Me-18:1; Fig. 6c) are in agreement with a Δ11 double bond in both 4-Me-17:1 and 4-Me-18:1 fatty acids.

Mass spectra of (a) 4-methyl-octadecanoic acid trimethylsilyl ester, (b) 4-methyl-octadecanoylpyrrolidide, and (c) bis-trimethylsilyl ether derivative of 4-methyl-octadec-11-enoic acid trimethylsilyl ester.

Reports on the occurrence of unsaturated branched fatty acids in bacteria are rather scarce. 11-Me-18:1 has been detected in Mycobacterium fallax [23]. Furthermore, 11-Me-18:1 and 11-Me-18:2 fatty acids have been detected in a marine bacterium (Shewanella putrefaciens) where they are thought to be precursors of furan fatty acids [24]. Furan fatty acids were not detected in the total cellular fatty acids of strain CV2803T grown on 1-pentadecene and 1-hexadecene, indicating that 4-Me-17:1Δ11 and 4-Me-18:1Δ11 were not intermediates of furan fatty acid synthesis. Moreover, the formation of these fatty acids was influenced by the growth substrate (Fig. 5), which rather suggested that 4-Me-17:1Δ11 and 4-Me-18:1Δ11 were derived from the catabolism and/or anabolism of n-alkenes by strain CV2803T. The detection of 4-Me-17:0 and 4-Me-18:0 fatty acids, as well as vaccenic acid (18:1Δ11) (Fig. 5), might indicate that 4-Me-17:1Δ11 and 4-Me-18:1Δ11 fatty acids were formed by desaturation of their saturated homologues. 4-Me-branched saturated fatty acids are known to constitute intermediate of n-alkanes degradation by some denitrifying [25] and sulphate-reducing [18] bacteria. Although the complete pathways for the degradation of n-alkenes by strain CV2803T still remain unknown, the present results indicate that 4-Me-branched fatty acids can also be formed from n-alkenes by sulphate-reducing bacteria. Moreover, as far as we know, this is the first report of Δ11-unsaturated 4-Me-branched fatty acids in bacteria, suggesting that these compounds could constitute specific metabolites of n-alkene degradation by sulphate-reducing bacteria. Further studies of the metabolic pathways of n-alkene degradation by sulphate-reducing bacteria are undoubtedly needed.

Acknowledgements

We thank Laurence Casalot for her careful English reading. This work was supported by grants from the ‘Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), the Elf company (GDR Hycar No. 1123), and by the European Commission through the MATBIOPOL Project (contract EVK3-CT99–00010).