Version française abrégée

Les compositions isotopiques en O2 et N2 de l'air expiré par 10 sujets sains, présentant des caractères physiologiques aussi différents que possible, ont été mesurées. Les résultats montrent que le fractionnement des isotopes de O2, ainsi que de ceux de N2, est proportionnel à la fraction de O2 utilisée par la respiration. La respiration consomme préférentiellement 16O, mais il semble qu'une faible fraction de 14N soit aussi utilisée.

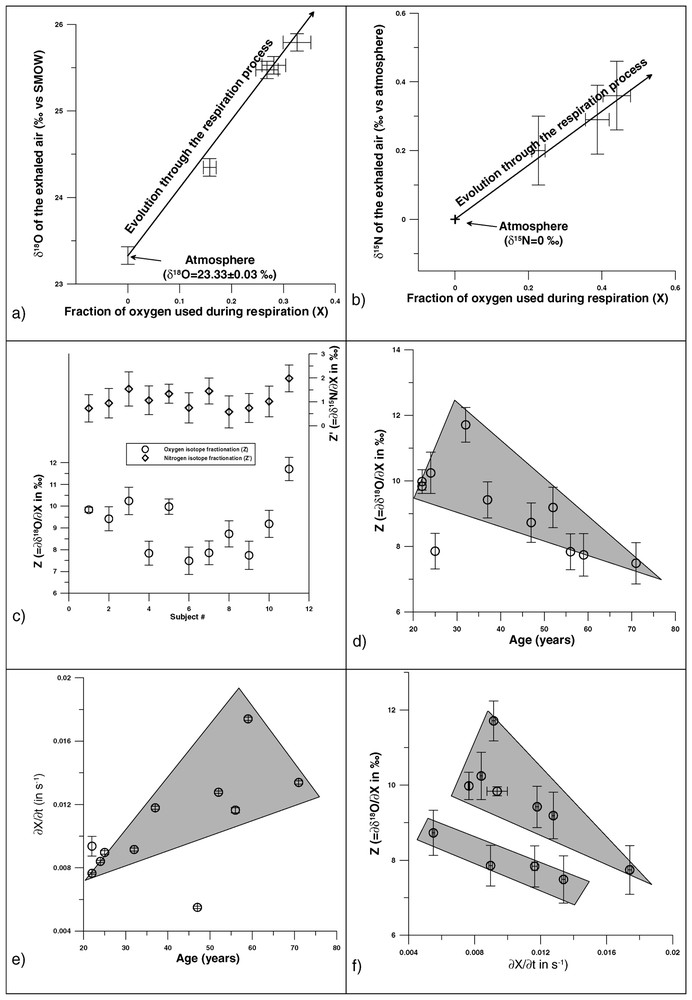

L'amplitude du fractionnement (normalisée à la consommation de 100 % de O2), est représentée par la variable Z pour O2 et pour N2. L'influence de certains paramètres physiologiques sur le fractionnement isotopique lors de la respiration a été analysée. Les résultats montrent diverses tendances. Plus le sujet est âgé, moins il fractionne le O de l'air. Ceci peut s'expliquer par une augmentation du taux de fixation de O2 avec l'age. Pour un même temps de rétention de l'air inspiré, un sujet ayant un taux de fixation de O2 plus élevé aura consommé plus de O2 (et donc de 16O). Son fractionnement sera donc plus faible (cette remarque sera corroborée plus tard dans la discussion par l'étude des relations Z-taux d'hémoglobine). Il est possible de distinguer deux familles de sujets, à l'intérieur desquelles la relation existant entre Z et le taux de fixation de O2 est conservée. Malheureusement, lors de l'augmentation du taux de fixation de O2, il n'est pas possible de distinguer le processus de diffusion moléculaire de celui de création d'oxyhémoglobine. Les autres paramètres physiologiques considérés semblent ne pas avoir d'influence sur le fractionnement de O2. Notamment, les fumeurs (sujets 9 et 10) présentent des valeurs de Z similaires à celles des non-fumeurs (sujets 1, 2 et 7), en contradiction avec les conclusions d'Epstein et Zeiri. L'étude d'un sujet ayant effectué un don du sang confirme qu'il existe une relation positive entre le fractionnement en O2 et le taux d'hémoglobine ( , où Hb représente le taux d'hémoglobine). Plus la concentration en Hb est élevée, plus le fractionnement isotopique est important. L'extrapolation de cette relation pourrait permettre d'estimer le fractionnement associé à l'étape de diffusion de la respiration. En effet, un sujet ayant un taux d'hémoglobine nul expirerait de l'O2 n'ayant subi que le processus de diffusion (c'est-à-dire sans formation d'oxyhémoglobine postérieure). L'ordonnée à l'origine de la droite reliant les deux paramètres donne donc une estimation de ce fractionnement associé à la diffusion pulmonaire. Cette valeur est constante, aux alentours de . Le signe négatif est inattendu, car la théorie prédit que la diffusion enrichit en isotope lourd le résidu de la réaction, représenté ici par l'oxygène expiré. Néanmoins, ceci impliquerait un fractionnement associé à la diffusion homogène pour tous les individus. Cette observation est renforcée par l'étude des isotopes de N2 (molécule ne subissant que la diffusion lors de la respiration). Le fractionnement isotopique normalisé semble être similaire pour tous les sujets. Si le fractionnement associé à la diffusion est constant et si le fractionnement normalisé en O2 varie suivant les individus, cela signifierait que l'étape isotopiquement dominante dans le processus de respiration est la formation d'oxyhémoglobine. L'influence d'un effort physique intense a aussi été testée. Après un effort soutenu de 40 min (squash), Z diminue de 1,7‰, tandis que le taux de fixation de O2 augmente (O2 s−1). Le fractionnement isotopique décroît donc avec l'activité physique. En tenant compte de la relation existant entre Z et Hb, lors d'un exercice physique, les poumons agissent comme si Hb diminuait, relativement.

Comme discuté précédemment, les isotopes de l'azote fractionnent eux aussi légèrement au cours de la respiration (l'azote expiré est enrichi en 15N). Le fractionnement observé est constant . L'existence d'un fractionnement requiert un rôle actif de N2 dans la respiration, même si, du fait des faibles valeurs de comparées à celles de Z, celui-ci est mineur.

1 Introduction

The preferential use of the 16O isotope during human respiration was observed by the early works of Dole and Jenks [1], Lane and Dole [2] and Dole [3]. The authors analysed gas samples involved in respiration by plants and by one sample from human individual. Later, Esptein and Zeiri [4] extended this systematic study of O2 fractionation during respiration by assessing potential effects of certain physiological parameters.

In the present study, exhausted air from 10 persons was analysed for both O and N (barely studied so far). In the choice of the individuals' panel, particular physiological characteristics were taken into account: age, weight, height, sex, smoking habits (Table 1).

Physiological characteristics of the studied individuals

| Individual | Age (years) | Height (cm) | Sex | Weight (kg) | Smoking (years) |

| 1 | 22 | 173 | M | 66 | 0 |

| 2 | 24 | 176 | M | 64 | 0 |

| 3 | 25 | 176 | F | 65 | 0 |

| 4 | 56 | 156 | M | 82 | 0 |

| 5 | 47 | 190 | M | 85 | 15* |

| 6 | 59 | 178 | M | 75 | ** |

| 7 | 52 | 160 | F | 59 | 10* |

| 8 | 71 | 167 | F | 67 | 21 |

| 9 | 22 | 179 | M | 69 | 9 |

| 10 | 37 | 173 | M | 70 | 25 |

* Smoked during ... and then stopped.

** Smokes occasionally.

2 Analytical methods

The individuals inhaled air and held their breath for between 10 and 60 seconds, and exhaled it into a Tedlar pack. A fraction of 2.5 ml was extracted and injected into a vacuum line for separation into N2 and O2 (under the form of CO2) for volumetric and isotope analyses. Proportions of O2 and N2 in each respired sample were manometrically determined during extraction. The isotope composition measurements were run on a Mat Delta E Finnigan mass spectrometer. Results are given in ‰ relative to the SMOW standard for O2 and atmosphere for N2. The reproducibility is 0.1‰ for O and N.

The fraction of O2 used during respiration is defined as , where V is the concentration of the exhaled O2 and A the concentration of the initial inhaled O2. Atmospheric analysis yielded a N2/O2 ratio of . It comes that , where B is the volume of N2 in the exhaled air (which is supposed to be equal to the inhaled one). The Z value, the normalised amplitude of the O2 isotope fractionation (normalised to the consumption of 100% of the O2), is defined as:

3 Gases cycle during respiration

Human respiration is a complex multistep process, in which blood supplies O2, inhaled through lungs, to the tissues that release CO2 [7]. Respiration can be modelled by a simple two-step model: (1) O2 diffuses through the pulmonary membranes with a diffusion constant and a fractionation factor , followed by oxy-haemoglobin formation with a reaction constant and a fractionation factor (followed by other reactions to finally form CO2). The global fractionation is a combination of the different fractionation factors. The slower the reaction is, the more influence it has on the determination of the final isotope fractionation.

4 Results and discussions

Fig. 1A and B show that human respiration fractionates inhaled-air O and N, characterised by a heavy-isotope enrichment for both exhaled O2 and N2 .

(A) O2 isotope fractionation during human respiration. (B) N2 isotope fractionation during human respiration. (C) Z and values for the studied individuals. (D) Relation between Z and the age. (E) Relation between the age and the O2 fixation rate. (F) Co-variations of Z and O2 fixation rate.

4.1 Oxygen

The isotopic effect on O2 is linearly correlated to the fraction of O2 used and is individual-dependent (Fig. 1A and C). The Z values plot into two distinct populations, the threshold being around . The age of the individual seems to be important in the determination of Z: the older the individual is, the lower Z is (Fig. 1D). This has possibly to be linked to the O2 fixation rate, which increases with the age of the individual, and on which depends Z (Fig. 1E). For a given time lapse, an individual with a higher X will consume more 16O. This leads to higher values of both the O of his exhaled air and the fraction of O2 used, compared to those of a younger individual, and ultimately to a higher Z value (as O/). The negative linear trend previously observed is conserved within both groups: the higher the O2 fixation rate is, the lower Z is (Fig. 1F). But, the faster the fixation performs, the faster the total of both diffusion and oxy-haemoglobin formation processes goes. It is thus impossible to determine which step is dominant. Among the other physiological parameters, nothing, and in particular smoking habits, seems to influence the expired O, unlike in a previous study, which indicated that smokers had higher Z values [4]. Smoking lays a tar coat on the pulmonary alveoli, disturbing the O2 diffusion through the alveolar-capillaries wall. If isotope fractionation differences were observed, it would mean that the diffusion step is prevalent in the determination of the global isotope fractionation. Results show no such discrepancies (Fig. 1C), as heavy smokers (individuals Nos. 9 and 10) have Z values similar to those of non-smokers (individuals Nos. 1, 2, and 7).

Individual 3 had a 400-g total blood donation, yielding two distinct samples: (1) under ‘normal’ physiological conditions, , and (2) shortly after the donation, . After a blood donation, the plasma volume quickly recovers, while restoration of the globular volume is physiologically longer [8]. The observed increase of the O2 fractionation, from 7.8 to 8.5‰ is in agreement with the positive linear relation between Z and the haemoglobin count (Hb) previously observed: Hb [4]. A blood donation of 400 g ( of the total blood volume) should have increased the Z value of 0.12‰ (Hb), instead of 0.7‰. The time elapsed between both samples (2.5 weeks) may not have been sufficient for the individual's globular volume to totally renew. The extrapolation of the relation existing between Z and Hb could give a better insight of the limiting factor for the O2 isotope fractionation. If an individual had a nil Hb, he would exhale O2 that would only undergo the isotope fractionation associated to O2 diffusion through the pulmonary membranes. The intercept in the Z–Hb relation thus gives an estimation of this fractionation: . This negative value is unexpected, as diffusion should imply an 18O depletion of the exhaled air. Nevertheless, it still may indicate that isotope fractionation induced by diffusion is constant (assumption later reinforced by results on N2, which only undergo diffusion). The fact that Z varies among individuals is thus an indication that the oxy-haemoglobin formation is the prevalent step in the determination of the final O2 isotope fractionation. This conclusion could be reinforced by further in vitro studies, especially focusing on the 18O affinity for hemoglobin.

4.2 Exercise influence

A sample was taken immediately after a 40-min intense effort (squash) and analysed on individual 6. The result yields a Z value of and a fixation rate of O2 s−1. Under normal physiological conditions, his fixation rate is only 1.7%O2 s−1 for . Vigorous exercise drastically increases the O2 fixation rate. During effort, lungs are to take O2 in the blood up to 20 times more than usual. This increase occurs in two ways: (1) increase of the number of open capillaries – O2 diffusion between the alveoli gas and the blood increases (∼3 times the value in rest conditions) –; (2) increase of the heart rate, with a concomitant increase of the pulmonary blood flow (4 to 6 times), the O2 fixation rate being also increased [9]. At the same time, Z decreases with the effort [4]. According to the relation with the haemoglobin count, this suggests that, as blood flow increases, lungs behave as if Hb were to decrease, relatively.

4.3 Nitrogen

Like O2, human respiration induces an isotope fractionation of the exhaled N2, linear with the consumption of O2 (Fig. 1B), variation between individuals is really small (average of ; Fig. 1C). The existence of a N2 isotope fractionation during human respiration implies an active role for this molecule. As values are significantly smaller than Z ones, this role is minor (but not nil) compared to O2. If the O2 isotope fractionation associated to diffusion is constant (), it can be assumed that it is also true for N2. This would thus explain why no noticeable differences are observed among the values, as N2 only undergoes pulmonary diffusion. Further experiments should consist in ensuring the independence of N towards Hb, and in performing in vitro analysis of bacterial strains (as nitrogen metabolism is controlled by the intestinal bacterial activity).

5 Conclusions

Our study confirms that humans preferentially use 16O in respiration, and may put to the fore that they also use 14N (in a smaller proportion). All isotope fractionations are linear with the amplitude of O2 consumption, and vary from one individual to the other (for O2). Physiological parameters such as exercise, haemoglobin count, O2 fixation rate and age (which influences the O2 fixation rate), all affect O2 fractionation. Isotope effect on N2 seems to be individual-independent. There is no clear evidence for determining the prevalent step (diffusion or O2 fixation) in human respiration, even if O2 isotopes favour the latest. But the study of the (non-)relation between Hb and both O2 and N2 should bring more constrains and help discriminating both processes. The existence of a blood flow measurement, displaying significant variations, would be a huge step in the comprehension and investigation of gas fractionations during human respiration.