1 Introduction

The HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein (NC) is a small basic protein characterized by two zinc fingers that preferentially binds single-stranded nucleic acids. Due to its chaperone activities, NC facilitates the rearrangement of nucleic acids into their most stable conformation, thus promoting nucleic acids hybridization and strand exchange [1,2]. As a consequence, NC is thought to chaperone several key steps such as the two obligatory strand transfers during reverse transcription. During the first strand transfer, NC has been shown to destabilize the secondary and tertiary structures of the transactivation response element TAR RNA and the complementary cTAR DNA sequence of the genomic RNA template and ssDNA, respectively [3–5], mainly by activating the transient opening (fraying) of TAR RNA and cTAR DNA terminal base pairs [6,7]. This enables then NC to increase the rate and extent of annealing of the complementary sequences [8–13] and block non-specific self-primed reverse transcription [10,14–16]. Both the initial destabilization and the subsequent annealing depend on the intact zinc fingers [5,17,18].

NC also stimulates the second strand transfer reaction [10,19–21] by removing the tRNALys,3 primer from the end of minus-strand DNA, and by annealing the ssDNA PBS sequence to its complement in minus-strand DNA. The activity of NC in facilitating plus-strand annealing has been related to its ability to destabilize the PBS DNA secondary structure and expose the nucleotides that are sequestered in the stem [4]. This, in turn, is thought to facilitate base pairing with the PBS sequence in ssDNA [4]. While the zinc fingers contribute to the role of NC in tRNA primer removal from minus-strand DNA, they seem dispensable for the subsequent annealing of PBS with its complement [10].

To gain further information on nucleic acid/protein interactions, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) has been shown to be useful [22–26]. This method analyses the fluctuations of fluorescence intensity in the very small volume obtained either with a confocal microscope or two-photon excitation. Analysis of these fluctuations through an autocorrelation function provides information on the phenomena that generate these fluctuations and the average number of fluorescent molecules in the excited volume. In the simplest and most common case, fluorescence fluctuations mainly occur from diffusion inside and outside the excited volume and from triplet blinking (conversion between the fluorescent singlet state and the non-fluorescent triplet state). If additional chemical or physical mechanisms induce transitions between states of different brightness during the diffusion time, information on the dynamics of these mechanisms could be additionally derived from the autocorrelation curves. This has notably been used for characterizing the dynamics of DNA hairpin-loop fluctuations [6,27–30] as well as RNA structural transitions [31].

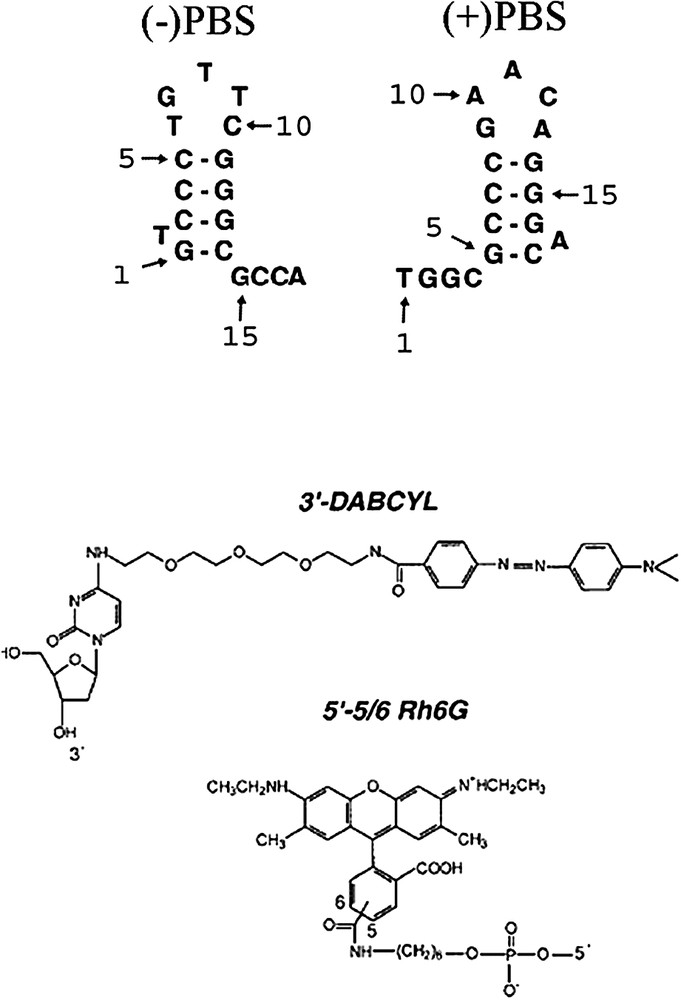

In this context, to further illustrate the potency of FCS for getting information on protein/nucleic acid interactions, we will review and extend herein our recent work on the chaperone properties of NC on PBS DNA and PBS DNA sequences [32]. By using fluorescently labelled oligonucleotides corresponding to PBS and PBS sequences (Fig. 1) respectively, we found that NC activates the transient melting of both sequences during their ‘breathing’ and promotes the formation of homodimers. Using PBS mutants, the homodimers were shown to mainly rely on kissing interactions through the loops. Both NC-promoted melting and homodimer formation are thought to be of importance for the second strand transfer and recombination.

Structures of PBS derivatives and dyes used in this study. The selected (+)PBS sequence is the cDNA copy of the PBS RNA sequence from the MAL strain.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

NC(12–55) peptide was synthesized as previously described [33] and stored lyophilized in its zinc-bound form. Its purity was greater than 98%. An extinction coefficient of 5700 M−1 cm−1 at 280 nm was used to determine its concentration.

Doubly and singly labelled DNA oligonucleotides were synthesized at a 0.2-μmol scale by IBA GmbH Nucleic Acids Product Supply (Göttingen, Germany). The terminus of the oligonucleotides was labelled by 6-carboxyrhodamine (Rh6G) via an amino-linker with a six-carbon spacer arm. The terminus of the doubly-labelled oligonucleotide was labelled with 4-(-dimethylaminophenylazo)benzoic acid (DABCYL) using a special solid support with the dye already attached. Oligonucleotides were purified by the manufacturer by reverse-phase HPLC and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The purity of the labelled oligonucleotides was greater than 93%. Extinction coefficients of 153 900, 113 400, 151 380, 171 990 and 175 680 M−1 cm−1 at 260 nm were used to calculate the concentrations of PBS, ΔLPBS, T7PBS, LPBSi and PBS, respectively. All the experiments were performed at 20 °C, in 25 mM Tris, 30 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5.

2.2 UV-visible absorption and fluorescence spectroscopy

Absorption spectra were recorded on a Cary 400 spectrophotometer. Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded on a FluoroMax spectrofluorometer (Jobin-Yvon) equipped with a thermostated cell compartment. Time-resolved fluorescence measurements were performed with a time-correlated single photon counting technique, as previously described [17]. The excitation and emission wavelengths were set at 480 and 550 nm, respectively. Time-resolved data analysis was performed by the maximum-entropy method using the Pulse5 software [34]. The mean lifetime was calculated from the fluorescence lifetimes, , and the relative amplitudes, , by . The population, , of dark species in the doubly labelled PBS derivatives was calculated by [32]:

| (1) |

2.3 FCS setup and data analysis

FCS measurements were performed on a two-photon platform including an Olympus IX70 inverted microscope, as described [6,35]. Two-photon excitation at 850 nm is provided by a mode-locked Tsunami Ti:sapphire laser pumped by a Millenia V solid-state laser (Spectra Physics). The measurements were carried out in an eight-well Lab-Tek II coverglass system, using a 400-μl volume per well. The focal spot is set about 20 μm above the coverslip. The normalized autocorrelation function, is calculated online by an ALV-5000E correlator (ALV, Germany) from the fluorescence fluctuations, , by , where is the mean fluorescence signal and τ is the lag time.

The analysis of can provide information about the underlying mechanisms responsible for the intensity fluctuations such as diffusion of the particles, electronic transition within the molecules and transitions between states of different brightness. For an ideal case of freely diffusing monodisperse fluorescent particles undergoing triplet blinking in a Gaussian excitation volume, the correlation function, , calculated from the fluorescence fluctuations can be fitted according to [36]:

| (2) |

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Evidence and kinetics of PBS fraying

Since NC has been shown to activate the kinetics of cTAR DNA fraying, our first objective was to investigate whether, by analogy to cTAR DNA, both PBS and PBS DNA (Fig. 1) also undergo a mechanism of fraying [6]. To this end, PBS derivatives labelled at their end by 6-carboxyrhodamine (Rh6G) and their end by 4-(-dimethylaminophenylazo)benzoic acid (DABCYL) were used. It has been previously shown for various stem-loop (SL) sequences that the dyes form a non-fluorescent (dark) heterodimer when the SL is closed [6,37]. In contrast, melting of the SL secondary structure by temperature or NC removes the two dyes from each other and restores the fluorescence of Rh6G. Experiments were performed in a buffer containing 25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 30 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM MgCl2, which is adequate for the evaluation of NC destabilizing properties [6,7,17,27,32].

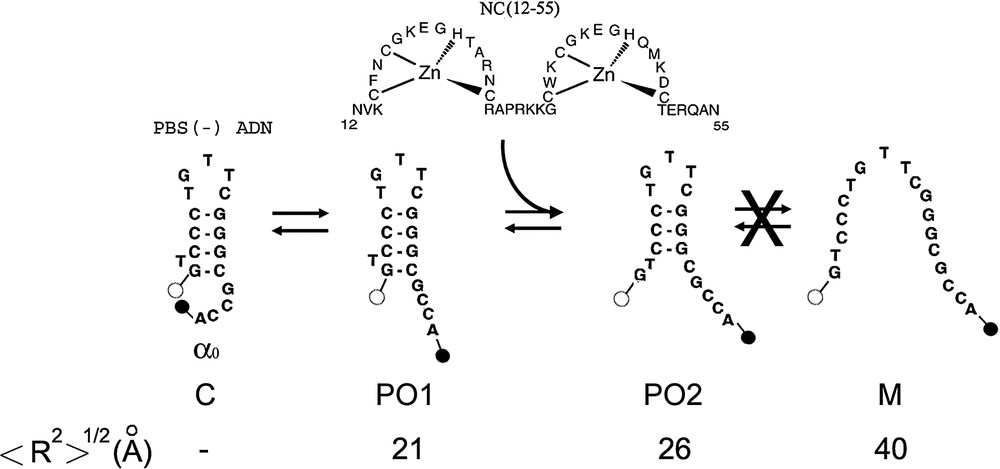

Time-resolved fluorescence studies indicated that both doubly labelled PBS and PBS sequences are largely in a dark non-fluorescent state (Table 1) where the stem is closed and the two dyes are associated close together (Fig. 2). The population, , corresponding to these dark species represents about 76 and 69% for PBS and PBS, respectively. The remaining species are characterized by lifetimes that are generally less than the corresponding lifetimes of the singly labelled species, suggesting that they may correspond to partly melted species with fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between Rh6G and DABCYL [6,7,17]. Due to the complex decay of Rh6G in both singly and doubly labelled derivatives, no clear correspondence between their lifetimes could be established. Nevertheless, due to its high value, the 3.79-ns lifetime of the doubly labelled species can safely be considered as being due to the reduction, by energy transfer, of the 4.27-ns lifetime of the singly labelled derivative. Similarly, the 1.57-ns lifetime of Rh6G--(–)PBS--DABCYL can be associated with either the or lifetimes of the singly labelled species. As a consequence, energy-transfer efficiencies, E, were calculated by: , where and are the fluorescence lifetimes of the doubly and singly labelled oligonucleotides, respectively. The calculated E values are 0.12 for the 3.79-ns component and 0.27 and/or 0.59 for the 1.57-ns component, respectively. Next, these values were used together with the Förster distance, for the (Rh6G, DABCYL) couple [17] to calculate the interchromophore distance, R, by using . Accordingly, interchromophore distances of 18 Å (and/or 24 Å) and 28 Å were calculated for the putative conformational states associated with the and lifetimes of the doubly labelled species, respectively. Noticeably, it has been checked by time-resolved anisotropy that the dyes at both and ends exhibit a fast local mobility, allowing them to sample many orientations during the transfer period (data not shown). As a consequence, orientation factors may not bias the interchromophore distances. These distances could be compared with the theoretical distances calculated using the wormlike chain (WLC) model [38] by considering the melted fraction of the stem as a continuous single strand (Fig. 2). By using this model, the mean square end-to-end distance, , is given by:

| (3) |

Time-resolved fluorescence parameters of singly and doubly labelled (−)PBS and (+)PBS sequencesa

| r a | ||||||||||||

| Rh6G--(−)PBS | − | − | − | − | 0.39 | 53 | 2.15 | 10 | 4.27 | 37 | 2.00 | − |

| Rh6G--(−)PBS--DABCYL | − | 76 | 0.12 | 15 | 0.44 | 6 | 1.57 | 2 | 3.79 | 1 | 0.41 | 20.0 |

| Rh6G--(−)PBS--DABCYL | 5 | 82 | 0.13 | 7 | 0.50 | 6 | 1.73 | 3 | 3.62 | 2 | 0.89 | 12.4 |

| Rh6G--(+)PBS | − | − | − | − | 0.21 | 59 | 0.79 | 29 | 3.96 | 12 | 0.83 | − |

| Rh6G--(+)PBS--DABCYL | − | 69 | 0.10 | 25 | 0.70 | 5 | − | − | 2.83 | 1 | 0.31 | 8.7 |

| Rh6G--(+)PBS--DABCYL | 5 | 78 | 0.15 | 10 | 0.97 | 8 | − | − | 2.82 | 4 | 0.96 | 4.0 |

a The oligonucleotide concentration was 0.5 μM. r designates the ratio of nucleotides to NC(12–55) peptide. The relative amplitude, , of the dark species is calculated by Eq. (1). The lifetimes, , and relative amplitudes, , of PBS sequences are expressed as means for at least three experiments. The standard deviations are usually below 10% for the lifetimes and below 15% for the amplitudes. designates the ratio of the fluorescence intensity of the singly labelled derivative in the absence of peptide to that of the doubly labelled one in the absence or in the presence of NC(12–55).

Proposed scheme of (−)PBS fraying. This scheme is established on the basis of the time-resolved data in Table 1. The dark closed form C is associated with the population. In the partly opened species 1 (PO1), no base pair is melted but the dyes are no more in contact. PO1 is thought to be associated with the lifetime of Rh6G--(−)PBS--DABCYL. The PO2 species in which the terminal G–C base pair is melted, may be associated with the lifetime of Rh6G--(−)PBS--DABCYL. Due to the multiplicity of Rh6G lifetimes, the and lifetimes cannot be unambiguously associated with one of these species. Alternate PO cannot be excluded, but our data do not support the presence of the fully melted M species. NC(12–55) is thought to activate the melting of mainly the terminal base pair. The theoretical interchromophore distances, , for the various species were calculated according Eq. (3).

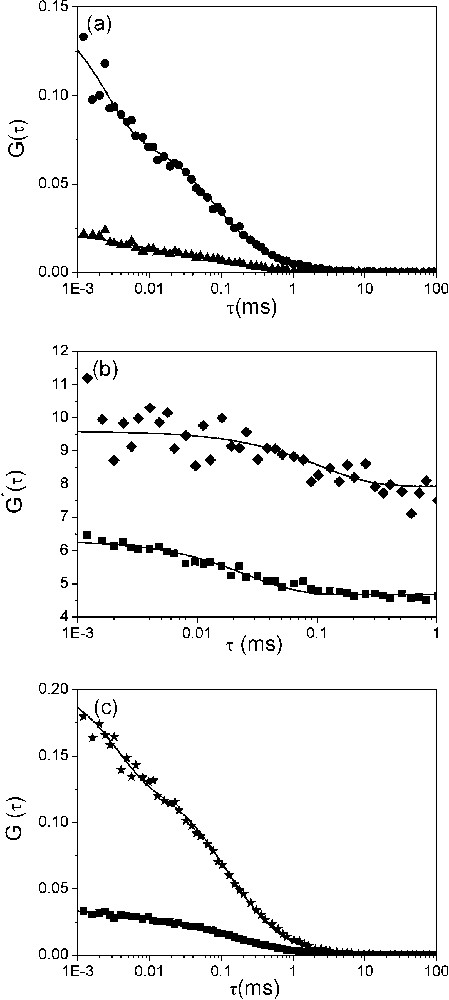

To get further information on the dynamics of PBS fraying, FCS with two photon excitation was performed. For singly labelled PBS derivatives, fluorescence fluctuations are thought to mainly occur from diffusion in and out the excited volume and from triplet blinking (conversion between the fluorescent singlet state and the non-fluorescent triplet state). In line with this assumption, the autocorrelation curves of both Rh6G--PBS (Fig. 3a) and Rh6G--PBS (data not shown) could be adequately fitted with Eq. (2), providing an average number, N, of molecules in the excited volume in excellent agreement with the theoretical number calculated from the concentration of molecules in solution. In addition, from the comparison with TMR taken as a reference, a diffusion constant, , of and could be calculated for PBS and PBS, respectively (Table 2). This value can be compared with the theoretical diffusion constant, , calculated by modelling PBS as a rod-like double-stranded DNA of 6 bp (if we assume that the loop is equivalent to two base pairs):

| (4) |

Dynamics of the fraying of (−)PBS sequences. (a) Autocorrelation curves of singly (▴) and doubly labelled (●) (−)PBS sequences at a 0.5 μM concentration. Solid lines correspond to fits of the experimental points with Eq. (2). The triplet lifetime, , and the fraction of molecules in triplet state, , were typically about 3 μs and 50%, respectively. (b) Ratio between the autocorrelation curves of doubly and singly labelled (−)PBS sequences. The ratios were obtained either in the absence (♦) or in the presence (■) of NC(12–55). The solid line is an exponential fit (see text) with the parameters given in Table 3. (c) Effect of NC(12–55) on the dynamics of (−)PBS fraying. NC(12–55) was added at a ratio of five nucleotides per peptide to the singly (■) and doubly (★) labelled (−)PBS sequences. The solid lines are fits to experimental points as above.

FCS parameters of the interaction of NC(12–55) with PBS derivativesa

| r | ||||

| (−)PBS | − | 9.9±0.3 | 1.5–8.1b | 0.5±0.1 |

| 5 | 7.4±0.4 | 1.4–7.2b | ||

| (+)PBS | − | 8.3±0.5 | 1.5–8.1b | 0.6±0.1 |

| 5 | 7.7±0.3 | 1.4–7.2b | ||

| T7(−)PBS | − | 10.0±0.7 | 1.5–8.1b | 0.9±0.1 |

| 5 | 7.7±0.2 | 6.1–10.6c | ||

| ΔL(−)PBS | − | 9.4±0.2 | 1.5–8.1b | 0.8±0.1 |

| 5 | 8.5±0.6 | 6.1–10.6c |

a The experimental diffusion coefficient, , was calculated from the apparent diffusion time as described in § Materials and methods. Both the apparent diffusion time and the average number of molecules in the illuminated volume are obtained by fitting the data of Fig. 5 to Eq. (2). The parameter describes the ratio of the average number of molecules in the presence of NC(12–55) to that in the absence.

b is the theoretical diffusion coefficient calculated from Eq. (4) using the rod-like model.

c calculated from the Stokes–Einstein equation using the spherical model.

Fitting the autocorrelation function of the doubly labelled PBS with Eq. (2) provided a significantly lower value than for the singly labelled derivative, suggesting additional fluorescence fluctuations with kinetics similar or faster than the diffusion constant. By analogy with cTAR molecules [6,27], these additional fluctuations may be associated with the fraying, which leads to transient stem openings and thus, transitions between the dark closed state and fluorescent open states. Additional information was obtained by calculating the ratio between the autocorrelation curves of the doubly and singly labelled PBS derivatives (Fig. 3b). As expected for a two-state model between a fluorescent and a non-fluorescent form, this ratio can be fitted with a monoexponential decay: , where B designates the amplitude, A is the limit value of and is the reaction time [28]. This in turn can be used to calculate the opening and closing rate constants describing the stem terminus transient openings by:

| (5) |

Effect of NC(12–55) on the kinetics of (−)PBS fraying, as determined by FCS

| r | ||||

| − | 110 ± 5 | 2300 ± 100 | 7000 ± 200 | 0.32 |

| 5 | 25 ± 1 | 7300 ± 400 | 33 000 ± 2000 | 0.22 |

3.2 NC destabilizes PBS secondary structure and promotes its dimerisation

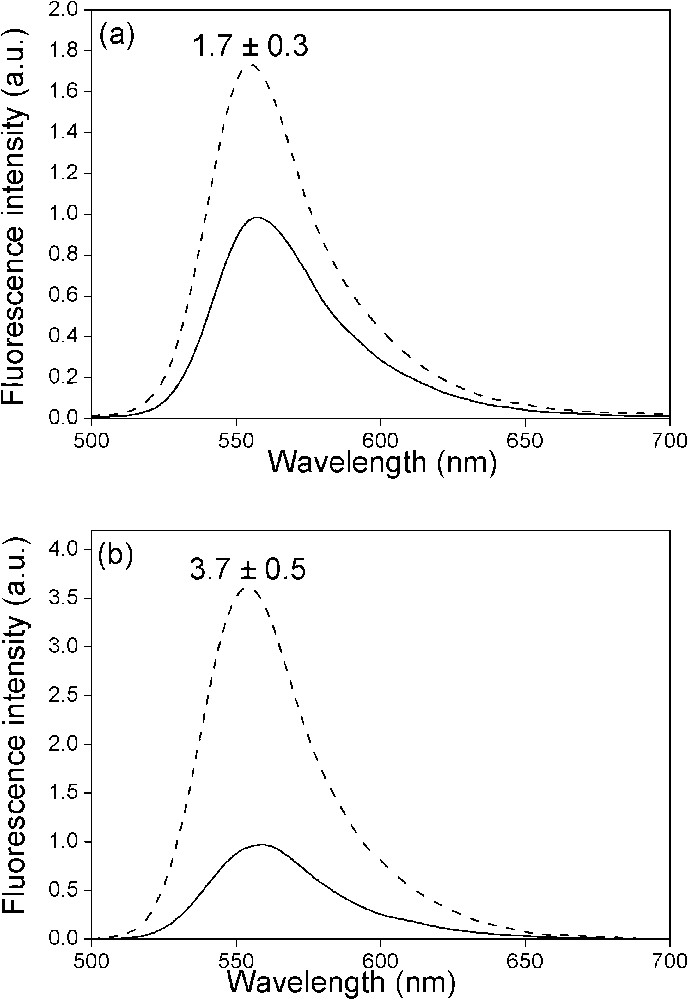

To investigate NC destabilizing effect on PBS derivatives, we used the NC(12–55) derivative, which contains the zinc-finger motifs but, in contrast to the native NC(1–55) protein, does not aggregate the oligonucleotides [43]. Since PBS and PBS sequences bind up to three NC(12–55) peptides with affinities of and , respectively [32], this peptide was added at a ratio of 5 nucleotides per peptide to 0.5 μM PBS to fully coat the oligonucleotides. NC(12–55) induces no significant change in the individual lifetimes of the doubly labelled PBS and PBS sequences (Table 1), suggesting that NC does not generate new species but only modifies the equilibrium between the species already existing in the absence of peptide. Moreover, in sharp contrast with cTAR [6,7,17], NC(12–55) does not reduce the value, and thus the population of closed species. In fact, the limited NC-induced fluorescence intensity increase observed for both PBS and PBS sequences (Fig. 4) is mainly due to a redistribution of the population associated with the short-lived lifetime to the benefit of the populations associated with the long-lived lifetimes. This suggests that the peptide induces only a limited redistribution between the partly opened species, in line with the modest NC-induced disruption of PBS secondary structure evidenced by NMR [4] and in contrast with the large effect of NC on cTAR DNA [6,7,17].

Effect of NC(12–55) on the fluorescence spectra of the doubly labelled PBS derivatives. The spectra of (−)PBS (a) or (+)PBS (b) were recorded at a 0.5 μM concentration either in the absence (solid) or in the presence (dotted) of NC(12–55) added at a ratio of five nucleotides per peptide. Excitation wavelength was 480 nm. The NC-induced fluorescence increase is indicated as mean ± standard error of the mean for three independent experiments.

These differences between cTAR and PBS cannot be related to the oligonucleotide stabilities since the values of PBS, PBS [32] and cTAR DNA [7] are similar. In fact, NC destabilizing activity merely relies on the free energy changes afforded by destabilizing motifs like loops and bulges regularly positioned within the SL secondary structure [27]. As a consequence, NC is only able to melt a limited number of consecutive base-pairs in a double-stranded segment. The number of consecutive base pairs that can be melted by NC depends on the base composition of the segment, and notably the number of G–C base pairs [27]. Our data suggest that NC is unable to melt the 4 G–C-containing B-helical double strand that constitutes the stem of PBS sequences [4,32]. In fact, since NC only increases the average melting within the population of partly melted species (Table 1), NC activates only the melting during the normal ‘breathing’ of the stem associated with the fraying mechanism. Since the destabilizing component of NC chaperone activity is mainly associated with the zinc finger domain [17], the limited NC-induced destabilization of PBS and PBS sequences evidenced here may explain the poor sensitivity on NC zinc fingers of the annealing of PBS in ssDNA to its complement in minus-strand acceptor DNA [10]. Noticeably, these conclusions might be modulated if by analogy with the leader region of the RNA genome [44,45], the stem of both PBS and PBS sequences at the ends of the plus- and minus-strand DNA molecules, respectively, may be characterized by only three G–C base pairs. In this case, it is likely that NC would contribute to the stem destabilization.

NC(12–55) was found to strongly modify the autocorrelation curves of both singly- and doubly labelled PBS derivatives (Fig. 3c). Two important features could be observed. The first one is a significant decrease of the reaction time (from 110 to 25 μs) associated with the fraying mechanism (Table 3). As a consequence, NC increases both the and rate constants, indicating that by analogy with cTAR [27], NC activates the kinetics of PBS fraying. The increase in further strengthens the hypothesis that NC lowers the energy barrier for breakage of base-pairs [2,46,47]. In addition, the NC-induced increase of suggests that binding of NC to the melted arms of the stem probably reduces the electrostatic repulsive interactions and thus also favours the closing of the stem.

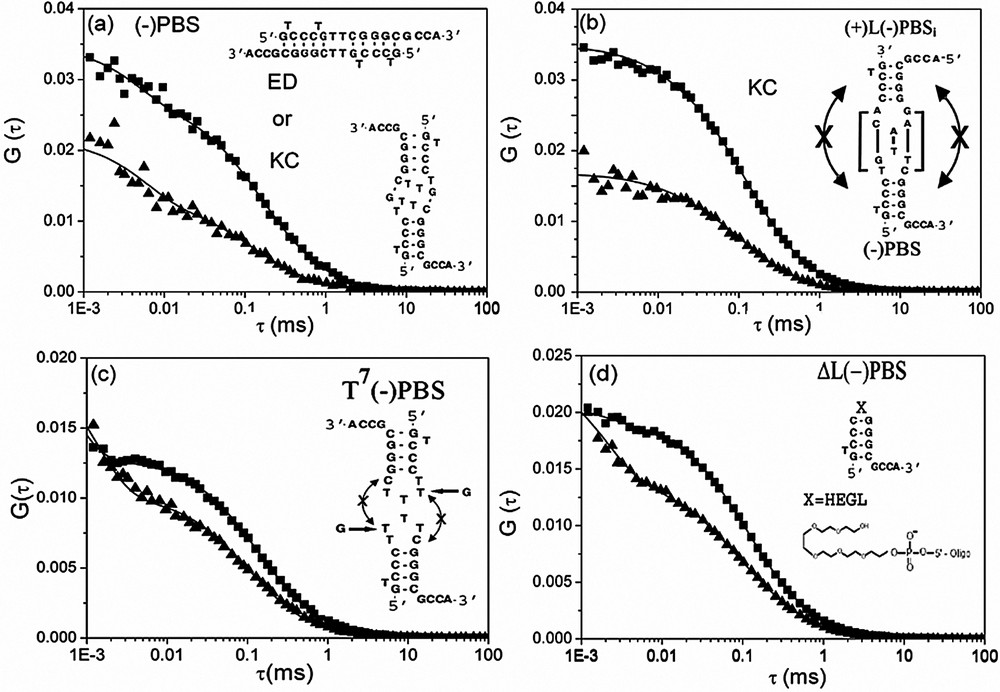

The second striking feature observed by FCS is the decrease by a factor of two of the average number of singly labelled PBS molecules in the excited volume, suggesting that NC(12–55) promotes the formation of PBS homodimers. Two types of dimers could be envisioned: kissing complexes and extended duplexes. Kissing complexes would be permitted by the partial autocomplementarity of the loop that would allow the formation of two intermolecular G–C base pairs (Fig. 5a). Extended duplexes would be very stable with ten intermolecular G–C base pairs, but are unlikely according to the inability of NC to melt the stem of both PBS and PBS sequences.

Interaction of NC(12–55) with (−)PBS derivatives, as monitored by FCS. The autocorrelation curves of (−)PBS (a), a mixture of (+)L(−)PBSi and (−)PBS (b), T7(−)PBS (c) and ΔL(−)PBS (d) were recorded at 0.5 μM of oligonucleotides (expressed in strands) in the absence (▴) and in the presence (■) of 1.8 μM of NC(12–55). The continuous lines are fits to the experimental points with Eq. (2). The putative kissing complexes (KC) or extended duplexes (ED) corresponding to the (−)PBS homodimers (a) as well as the (−)PBS/(+)L(−)PBSi kissing complexes (b) are represented.

To further demonstrate the formation of NC-induced kissing complexes, we tested the interaction of NC with several PBS mutants. In a first attempt, Rh6G--PBS was mixed with an equimolecular amount of Rh6G--LPBSi (Fig. 5b). In this last mutant, the loop of PBS was substituted by the PBS one to increase the stability of the kissing complexes and the stem was inverted with respect to that of PBS to prevent the formation of extended duplexes. Addition of NC(12–55) to this mixture decreased N by a factor of two, clearly indicating the formation of PBS/LPBSi kissing complexes. In sharp contrast, no significant decrease in N was observed when NC(12–55) was reacted with T7PBS (where the loop was no more autocomplementary) (Fig. 5c) or ΔLPBS (where the loop was substituted by an hexaethylenglycol HEGL tether) (Fig. 5d), confirming that PBS kissing complexes rely on the annealing of the partially autocomplementary loops. Finally, NC(12–55) was found to promote also PBS kissing complexes stabilized by two intermolecular G–C base pairs between the loops (data not shown).

Interestingly, in the absence of NC(12–55), the values of T7PBS, ΔLPBS and PBS were similar to that of PBS (Table 2), suggesting that these species have similar shapes and thus, similar secondary and tertiary structures. A significant decrease of the values was observed for all PBS derivatives in the presence of NC(12–55) but only small differences could be observed between species giving homodimers and those giving not. To address this intriguing point, the values were compared with the theoretical values calculated based on assumptions derived from the experimental data. In the case of PBS, and PBS, the NC-induced kissing complexes were approximated as 12-bp double-stranded rods coated by NC(12–55). According to the dimensions of NC(12–55) [48], the hydrodynamic diameter of the rod was increased by 10 to 25 Å to take into account the bound peptides. Using these assumptions, it was found that the values of these three PBS derivatives are close to the upper limit of the expected range. This may again result from the deviation of their shape from an ideal rod. In the case of T7PBS and ΔLPBS, the hydrodynamic diameter increase resulting from the binding of NC(12–55) to the short monomeric oligonucleotides is expected to deviate them even more strongly from a rod-like model. As a consequence, this model was substituted by the spherical model and was calculated by the Stokes–Einstein equation: . Using a radius, r, between 30 and 45 Å, the range was found to fully encompass the value. Accordingly, the values of all the complexes are in line with the conclusions derived from the NC-induced changes in N, further strengthening our conclusions on NC-promoted homodimers.

4 Conclusion

By combining FCS and fluorescence spectroscopy, we have shown that NC (i) activates the destabilization of both PBS and PBS secondary structures and (ii) promotes the dimerisation of these sequences through the formation of kissing complexes stabilized by two G–C Watson–Crick contacts. From these data, it may be inferred that NC also activates the formation of kissing complexes between the PBS sequence in ssDNA and the PBS sequence in the complementary minus-strand DNA. This may constitute the initial step in the NC-directed chaperoning of the second strand transfer during reverse transcription [19]. Since, in addition, NC increases the kinetics and extent of fraying of both PBS and PBS stems, NC may in a second step promote the nucleation of the extended duplexes.

Moreover, the HIV genome corresponds to a compact dimeric RNA where two identical RNA molecules are hold together by stable interactions at the end [49–52]. Homodimers with partially self complementary sequences may contribute to the stabilization and compaction of the genome in the viral nucleocapsid structure [53], thus contributing to the overall structure of the genome in the virus. In addition, since a close connection between dimerisation and recombination has been recently highlighted [54], the PBS homodimers stabilized by NC may facilitate the strand transfer events during viral DNA synthesis by reverse transcriptase, fuelling genetic recombination and thus viral diversity [54].

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to J.-L. Darlix and B.-P. Roques for discussion, and D. Ficheux for the synthesis of the peptide. This work was supported by grants from ANRS, Sidaction and the European Community (TRIoH). C.E. is a fellow from the French ‘Ministère de la Recherche’.