1 Introduction

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is an imaging technique that allows non-invasive and non-destructive acquisition of high-resolution images in intact opaque animals [1–5]. MRI has the advantage of delivering images in the three classic planes without reconstruction, and thus provides good geometric resolution images. Moreover, the high contrast for soft tissues makes this technique an ideal tool to examine these organs. The aforementioned technique has recently been used to investigate the anatomy of many osteichthyan species for alimentary purposes [2] or anatomical studies [1,5]. Being non-destructive, it provides good resolution pictures of the internal organisation of animals, whether alive or dead. This absence of direct manipulation or alteration is especially worthy of interest for rare, old and historical specimens, and several authors have provided detailed studies of the anatomy of alcohol preserved specimens belonging to taxonomic collections [1,5] using non-intrusive techniques. These works show that MRI examinations can be successfully applied to these specimens. Recently, a collaborative project at the University of California, San Diego between the Center for Scientific Computation in Imaging (CSCI), the Center for functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (CfMRI) and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO), built a Digital Fish Library (DFL) (http://www.digitalfishlibrary.org/about.php) consisting of MRI data of various fish species from alcohol preserved specimens to provide data for research and education. This project highlights the interest in MRI examinations; unfortunately in these images MRI parameters are not indicated and internal structures of animals are neither labelled nor compared to fresh or dissected animals. In the literature, RMI images of teleostean species have rarely been compared to what can be observed in fresh specimens. In the attempt to fill this gap, we led MRI examinations on several specimens of the common carp (Cyprinus carpio (L. 1758), Cyprinidae, Ostariophysii, Teleostei). We examined a specimen of common carp preserved in alcohol since 1970, a freshly dead fish of the same species and a recently sacrificed dead archerfish (Toxotes jaculatrix (Pallas, 1767), Toxotidae, Acanthomorpha, Teleostei). MRI examinations have been performed both with the specimen inside and removed from its container (a glass jar). Also, a sagittally-cut frozen/fresh common carp was used for comparison.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Specimens studied

Dead specimens of the common carp (Cyprinus carpio (L. 1758), Cyprinidae, Ostariophysii, Teleostei) were compared to one another: fresh specimens (Standard Length: 43.6 and 47.8 cm) caught by Baillet Pêche (F-44/Carquefou) and an alcohol preserved specimen (Standard Length: 31.9 cm), preserved in the “Collection Pédagogique” of the University of Nantes (Faculté des Sciences et Techniques) under the reference: UNSCIBA.Z 000930. This specimen was added to the collections in 1970, and has been in alcohol for 38 years. There is no record indicating that the specimen was fixed in formalin, before storage in alcohol. MRI was also conducted on a freshly killed banded archerfish (Toxotes jaculatrix (Pallas, 1767), Toxotidae, Acanthomorpha, Teleostei) (Standard Length: 8.9 cm) that had been purchased in a pet shop (Delbard, Brest, France).

2.2 Mechanical sections

For comparison, parasagittal mechanical sections (MS) were performed on a freshly killed, frozen common carp using an electric meat saw (La Bovida, BG).

2.3 Radiography

An alcohol preserved specimen was X-rayed in its jar, in lateral recumbency; using a Convix 30 Machine with a Universix 120 command at 46 kV and mA at 6.4 for 17 ms. Images were developed using a Fuji FCR 5000.

2.4 Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The MRI images were acquired using a 1 Tesla superconducting magnet (Harmony, Siemens) with a 30-cm horizontal bore super-conducting magnet. The matrix was . Specimens were kept at ambient temperature (20 °C) and placed on the scanning table in lateral recumbency for the fresh specimen and in the jar for the alcohol preserved one. A standard head coil was used. Sagittal localizer series were performed in order to delineate the slices of the images for each pulse sequence series. The acquisitions were performed using turbo spin echo sequences with a 3 or 4 mm slice thickness. Sagittal T1 weighed images (TR = 650 ms and TE = 13 ms) and T2 weighed images (TR = 5300 ms and TE = 105 ms) were recorded of the whole fish. As the specimens were dead animals, no injection of contrast agent, such as gadodiamide [6], could be performed.

3 Results

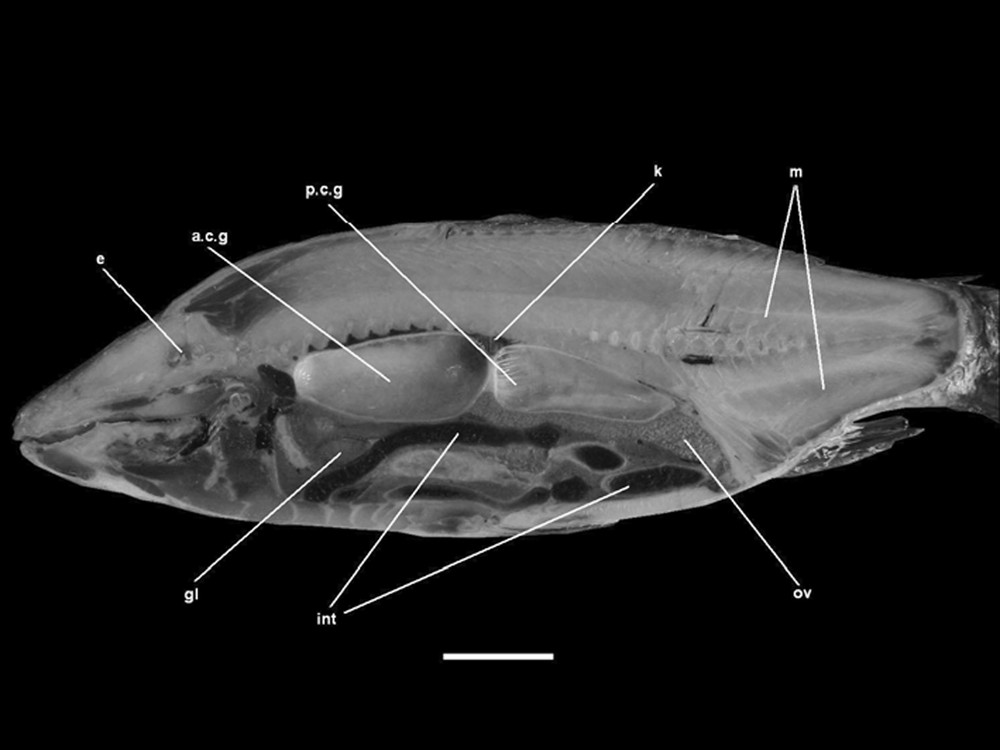

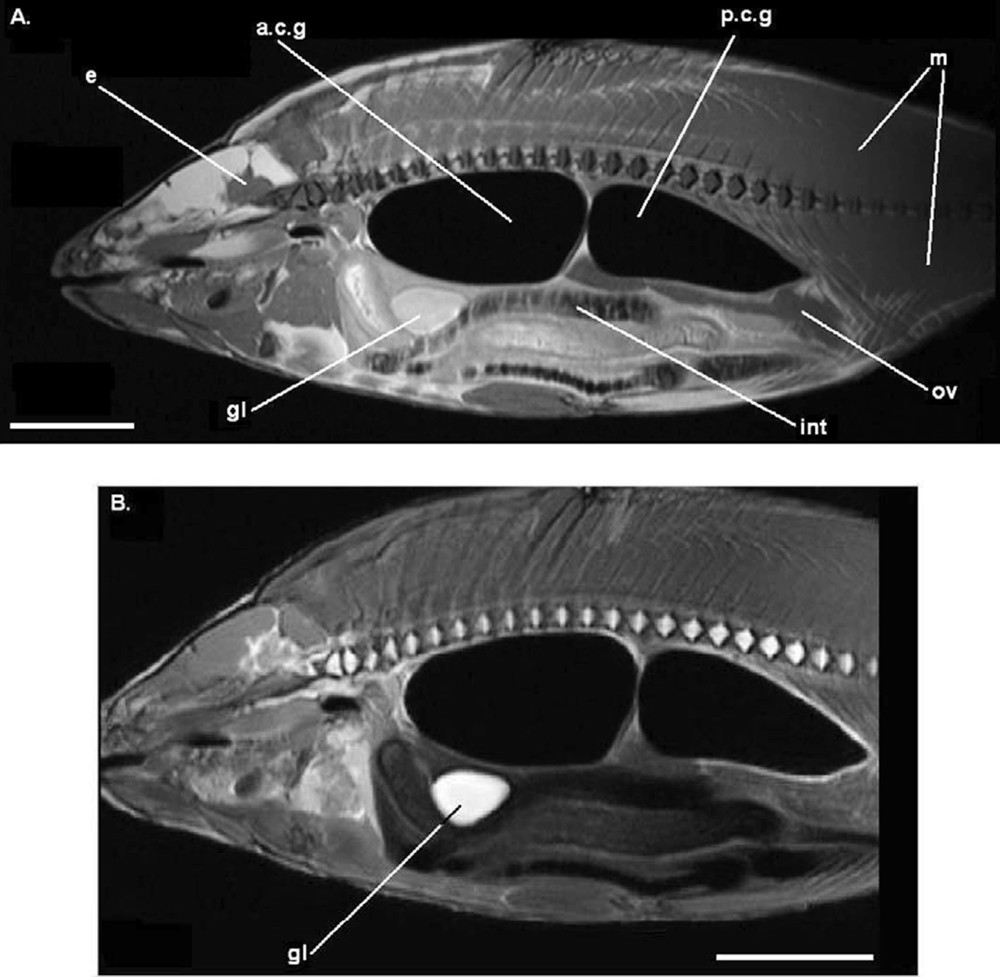

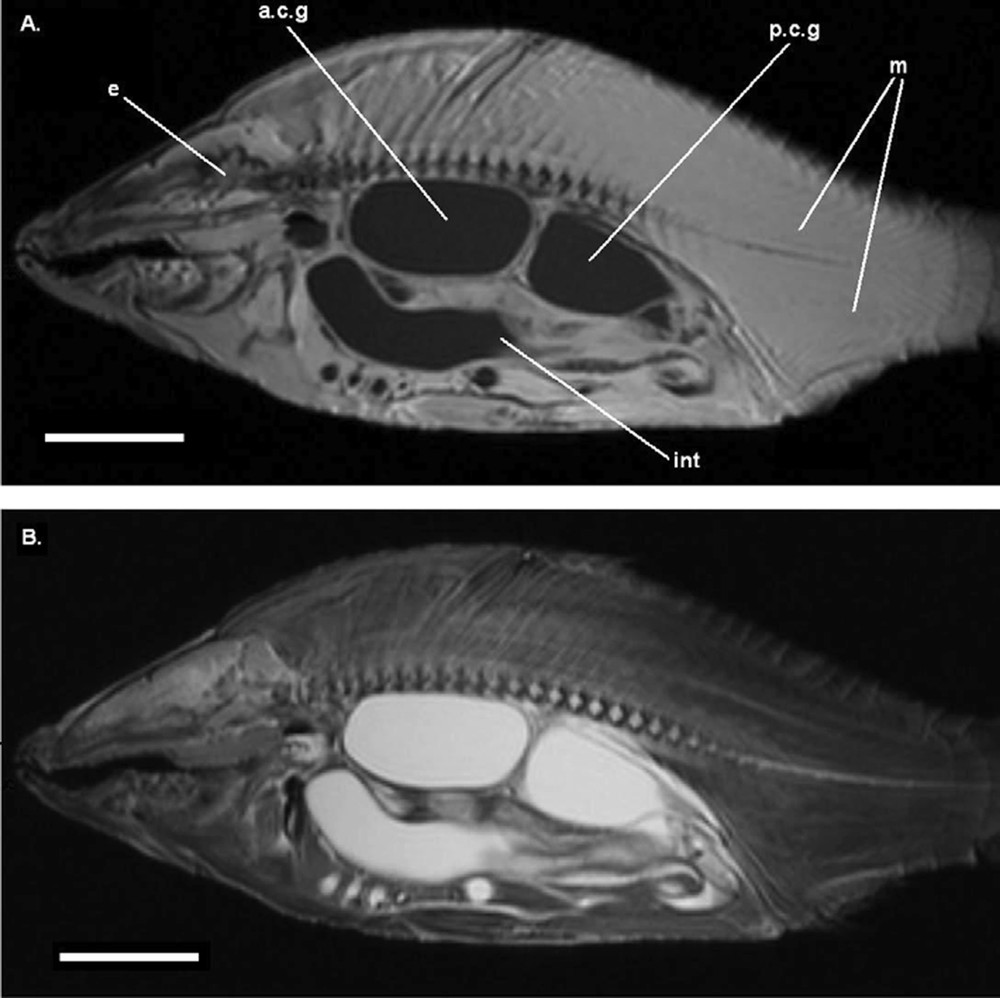

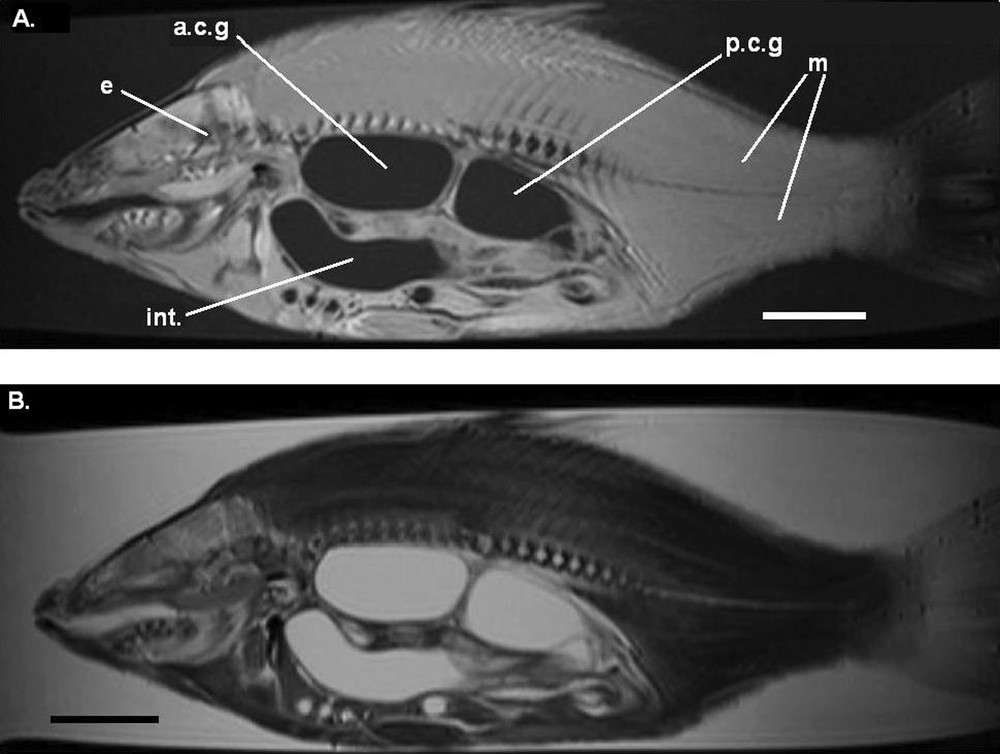

Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4 illustrate the main results of this study. The main result is that the gross anatomy of the animals can be visualized equally well with both the mechanical section and virtual (MRI) sections on each specimen, either fresh or alcohol preserved. Images are globally identical, providing the same information and showing that internal organisation of tissues and sizes of organs are not fundamentally altered by being preserved in alcohol for 38 years. The shape, size and morphology of muscles, rachis, gas bladder, digestive tract, ovary and nervous system can be visualised very clearly (Figs. 1–4), and no major difference concerning the disposition of internal organs can be detected between these techniques. In all cases, muscles and bony tissues appear in different shades of grey. In T1, air and alcohol have the same signal, and appear in black. Then in fresh specimens (FS) and alcohol preserved specimens (APS), internal cavities – filled with gas in FS (Figs. 2A–2B) and filled with alcohol in APS –, gas bladder to ventricle and digestive tract (Figs. 3A–4A), are black in T1. In T2, the air and liquids have different signals: air is shown as black, while liquids as light grey to white. In FS, the filled gall bladder is clearly visible in white in T2 (Fig. 2B). In APS, liquids and internal cavities filled with alcohol and are visible in light grey in T2 (Figs. 3B–4B–5). The gall bladder is not clearly visible in T2 because the bile has precipitated. As for the specimen in the jar, and preserved in alcohol (T2, Fig. 4B), the latter area appears in light grey as well in T2 (Fig. 4B).

Parasagittal section (MS) of a frozen common carp (FS). a.c.g: anterior chamber of the gas bladder, gl: gallbladder, int: intestine, k: kidney, m: muscles, ov: ovary, p.c.g: anterior chamber of the gas bladder. Scale bar indicates 5 cm.

Parasagittal image (MRI) on a fresh common carp (FS). A. T1-weighted image. B. T2-weighted image. Legends as Fig. 1. Each scale bar indicates 5 cm.

Parasagittal image (MRI) on an alcohol preserved common carp (APS), out of the jar. A. T1-weighted image. B. T2-weighted image. Legends as Fig. 1. Each scale bar indicates 5 cm.

Parasagittal image (MRI) on an alcohol preserved common carp (APS), still in the jar. A. T1-weighted image. B. T2-weighted image. Legends as Fig. 1. Each scale bar indicates 5 cm.

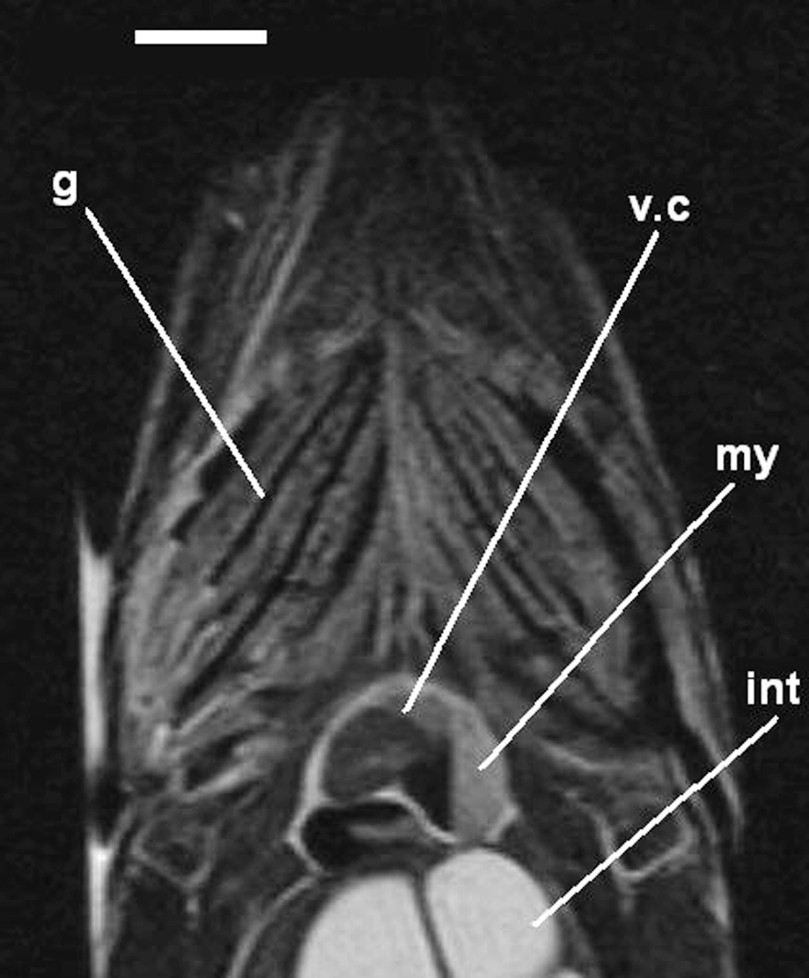

Detail of a coronal image (MRI) on an alcohol preserved common carp (APS), out of the jar (T2-weighted image). g: gills, int: intestine, my: myocardium, v.c: ventricle cavity. Scale bar indicates 1 cm.

It can be noticed that the contrast and the quality of the images are better with fresh specimens (Fig. 2). This point might be linked to the abundance of H atoms in the tissues: fresh specimens contain a greater amount of water (more than 75%) which is not the case in alcohol-preserved specimens. Therefore T1 and T2 compensations have to be performed systematically in order to be able to observe anatomical details. Fig. 6 shows the thickness of the ventricular myocardium in the carp. As the specimen is still immersed in liquid, the MRI examination of the specimen (APS) still in the jar realised in T2 offers a better contrast. This leads us to conclude that leaving the specimen in the jar during the MRI examination does not alter the quality of the images. This point is important as historical specimens are precious, and often in fragile and sealed recipients. MRI studies are, however, possible without tampering with the specimens and the jars where they are found. As metallic artefacts cause local modifications of the magnetic field [7], and thus affect the quality of images and the information they provide, it is important to verify that no magnetic metal is present inside or outside the jar. It is important to note that MRI examinations with a 1 Tesla magnetic field do not provide good anatomical images for small specimens (Fig. 7).

X-ray of an alcohol preserved common carp (APS), still in the jar. Scale bar indicates 5 cm.

Parasagittal image (MRI) on a fresh banded archerfish (FS). T1-weighted image. e: eye, g: gas bladder. Scale bar indicates 1 cm.

4 Discussion

The present study indicates that MRI examinations can be conducted on alcohol preserved specimens, even if they have spent a relatively long time (e.g., 38 years in our case), in preservative solution. The gross anatomy of animals can be easily investigated even on fragile and historical specimens. MRI appears to be very useful for the study of soft anatomy on these specimens and could be a valuable preliminary step to decide on future potential dissections of these valuable specimens. This technique is appropriate for soft anatomical studies performed using specimens from taxonomic collections, but can be replaced by classical X-rays (Fig. 6) and high-resolution desktop X-ray microtomography (CT-scan) for finer and 3D examinations of skeletal structures on similar specimens [8,9]. We found that leaving specimens in the jar does not affect the quality of the images. Therefore, the technique is worthy of interest for the management, the examination and the manipulation of the specimens preserved in taxonomic collections. Nevertheless, it must be pointed out that the size and thickness of specimens must be carefully considered. Small specimens, with a Total Length shorter than 10 cm and a mean thickness of less than 1.5 cm, are not suitable for MRI examinations with a 1 Tesla magnetic field (Fig. 7). Further studies and examinations are needed to define more precise protocols in order to build an anatomical database of MRI images and then to collect the wide range of information contained in the taxonomic collections.

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Lequet (Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Université de Nantes, Nantes, France) for access to specimens, A. Dettaï and G. Lecointre (Department Systématique et Evolution, MNHN, Paris, France) for advice and encouragement. We are indebted to D. Baron (IUFM de Bretagne, Brest, France), François Chapleau (University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) and Ian Nicholson (ENVN, Nantes, France) for their valuable comments and improvements of the manuscript.