1 Collective action of psychosurgery practitioners

Between 1950 and 1960, psychosurgery practices declined for good. At least, in Portugal, even before the introduction of chlorpromazine into psychiatric medication, the cases studied show not only a reduction in the occurrence of this practice, but also evidence that many psychiatrists avoided psychosurgery procedures.1

Several authors point to a European resistance to the practice of psychosurgery until the 1950s, emphasizing the boost that the Nobel Prize awarded to Egas Moniz induced in the acceptance of the method. We know today that the spread of psychosurgery has been unevenly distributed, from its early acceptance in Italy, Spain, United States, Brazil and other South American countries to its later adoption in other European countries.2 Anyway, it should be underlined that the relative uncertainty of results and the high risk involved turned this type of surgery, at least theoretically, into a solution of last resort.

In spite of the continued practice of psychosurgery until the present day, on a smaller scale, side effects, uncertainty, and theoretical void led to a general precaution about decision taking, percolated through ethical barriers. The historical judgment of old psychosurgery was harsh, and the most significant condemnation came from the practitioners themselves.

When, one decade ago, Portuguese neurosurgeons looked for knowledge and training on Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) techniques, they had to address Jean Stiglitz (Zurich), Andres Lozano (Toronto), Alim-Louis Benabid (Grenoble) or Tipu Aziz (London) [1]. The transition from the old to the new psychosurgery – admitting that DBS changed the paradigm from lesion to stimulation – had not, in the 1980s, any immediate expression in Portugal.

The discussion within the International Society of Psychosurgery preceding the Conference of 1970 showed that one part of the psychosurgery supporters wanted to exorcise the practice dating back to the 1930s and 1940s. Looking at the analysis of some inside historians [2], we can confirm that several members proposed to erase from history the Conference of 1948, in Lisbon, taking instead the one of 1970, in Copenhagen, as the very first. Walter Freeman, among others, who participated actively in the preparation of that conference, opposed this. He, along with other veterans, was victorious and finally, the Copenhagen conference of 1970 was numbered as the second one, recognizing intertwined connections between old and previous ideas and practices. Another sign of that desire to distance the old practices came through the change in the name of the entity organizing those conferences. The previous designation of International Society of Psychosurgery was then replaced by the new International Society of Psychiatric Surgery, adopted from the time of the Copenhagen conference onwards.

Other conferences took place throughout the seventies – the third in 1972 in Cambridge, the fourth in 1975 in Madrid, and finally the fifth in 1978, in Boston. The following conference, expected for Stockholm, had finally been cancelled under the argument that the power of attraction of psychosurgery was fading and the insistence on international psychosurgery conferences, by its specificity, was leading psychosurgeons into an isolated position. Ever since, the interventions of psychosurgeons (or the supporters of psychiatric surgery) would take place in all possible meetings, colloquiums, congresses or conferences where the subject of psychosurgery could be dealt with, abandoning the previous specific model. The last documents in the archives of the International Society of Psychiatric Surgery disclose the arrangements made with the organizing team of the International Congress of Psychiatry, held in Vienna, in 1983, to include a panel on the subject of psychosurgery and some presentations about this topic.

Looking at the insider historical works from the North American side, authors such as Andres Lozano are always using the term ‘psychiatric surgery’. In Belgium, a different term is used: Stereotaxic Neurosurgery for Psychiatric Troubles (neurochirurgie stéréotaxique pour troubles psychiatriques) [3], meanwhile in France, authors like Marc Lévèque keep the old designation of psychosurgery [4]. The formers seem to maintain the will to distance themselves from what can be seen as related to the old practices, while the latter keep the old designation, assuming that old and new psychosurgery are deeply entwined. In the history of psychosurgery, there were therefore two moments during which some of the main psychosurgery supporters wanted to distance themselves from the tradition of the field. The first one occurred at the beginning of the 1970s, and the second one towards the end of the 1980s, with the invention of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS). Ultimately, the required institutional acceptance has been progressively accomplished. The American Congress, answering to an interpellation of several critics against psychosurgery, some of whom asking for its interdiction, made a decision. In 1977 the National Commission for Human Protection of Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research (Commission nationale pour la protection d’humains soumis à la recherche biomédicale et comportementale) issued a report with recommendations aimed at regulating psychosurgery practices and related scientific research [5 (p. 59)].3 This Commission decided on some warnings, but ended up recognizing the therapeutic benefits of psychosurgery in some cases.

In 2002, the National Ethic Consultative Committee (Comité national consultatif d’éthique), questioned by Alim-Louis Benabid, among others, spoke in favor of psychosurgery practice and research. At that time, Alain Bottéro, a French psychiatrist, wrote a set of articles criticizing that decision and complaining of the lack of response from psychiatrists in spite of the transparency of the Committee's procedures [6].

Once the psychosurgery approach was applied to the most severe psychiatric troubles, good cooperation or conflicting opposition between psychiatrists and neurosurgeons would shape the perception of the surgery results and influence the fate of psychosurgery.

The dilution of psychosurgery conferences in broad psychiatric congresses and other related events was to bring both specialties to converge, as far as it was possible, and despite the ups and downs of the controversy, they nevertheless bonded together.

2 Enthusiasm about results

The scientific fragility of psychosurgery came mainly from its noticeable theoretical poverty from the start. From the very beginning, its pioneers confessed to induce changes that had repercussions in the mental life of patients but they did not understand the relationship between cause and effect.

Egas Moniz used to speak out against this kind of criticism – on the theoretical fragility of leucotomy – instead claiming that results were self-evident and spoke for themselves [7 (p. 25)], so that all efforts to convince peers, the media, patients and their relatives about the success and the alleged advantages of leucotomy had been skillfully focused in the shaping of results.

Hence, the results were rhetorically treated with an emphasized focus on the statistical perspective, despite the apparent contradiction between the qualitative approaches characterized by individual differences and deep analysis, on one side, and, on the other, leucotomy series of surgical operations that were supposed to treat all the patients the same way, with the same target, despite the differentiated psychiatric disorders.

To further prove the power of the treatment, a reduced range of categories was settled on to limit the scope of possible results, thus giving a more complete, sensitive and positive idea on them. Some ‘before and after’ pictures of patients were added, where the alleged ‘improvement’ appeared even more effective (Fig. 1). Finally, the auxiliary theories helped to decode these evidences by interpreting the visible metamorphoses after surgery.

Pictures used by Egas Moniz in his monography.

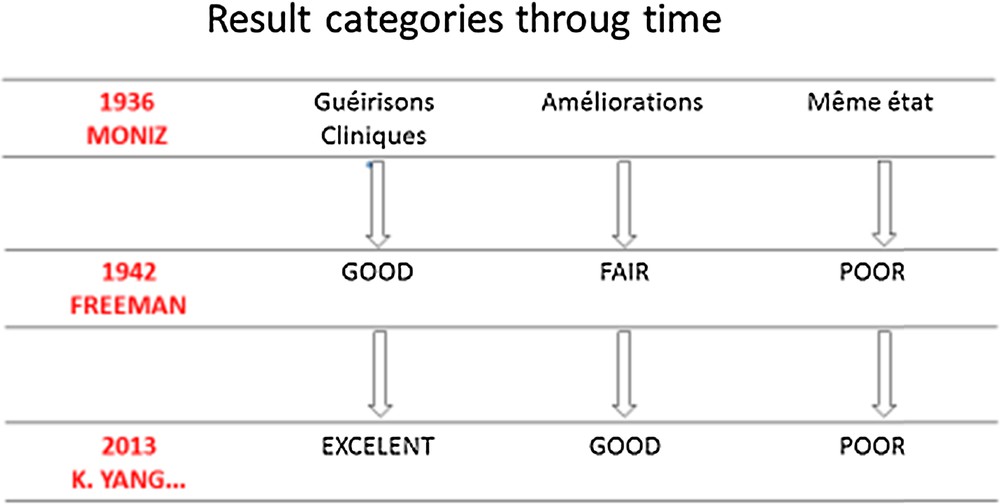

The first result tables published by Moniz and Freeman, but also by Le Beau and many others, did not incorporate certain categories (such as, for example, those of worsened or deceased patients). Under a very low degree of requirement, the record only stated the number or percentage of favorable cases. For Freeman, it was argued that in the worst cases, the method hardly improved the situation of patients – but there was nonetheless some improvement – while for Moniz, patients remained in the same unchanged state for the worse (Fig. 2). In this way, all the possible results of leucotomy and lobotomy published between 1936 and 1948 were favorably optimistic in spite of the accumulation of drawbacks and other failures later acknowledged.

Results categories through time.

To support the potential of persuasion, both Moniz and Freeman added, as we have already mentioned, photos of patients before and after surgery. The facial expression, hairstyle, posture and lighting showed how the operation had rendered them to be relieved of their psychological conditions (Fig. 1).

Furthermore they explained to patients and families that the at times daunting appearance of patients shown after the operation (indifference, lack of initiative, difficulty of concentration, confusion, dizziness and, more broadly, “childish attitudes”) was normal, expected and transient.

After a period in which most psychiatrists and neurosurgeons denied personality changes after leucotomy and assigned criticism to a wrong perception or bad faith from those who disagreed, they finally came to admit some negative and permanent changes. Eventually, Barahona Fernandes (Portuguese psychiatrist belonging to Egas Moniz team) and Walter Freeman developed a doctrine acknowledging and explaining personality changes. Fernandes named it “syntonic regression”– according to which patients returned to a previous phase, prior to the first manifestation of their psychosis (regression), becoming more extroverted (syntonic) facilitating psychotherapy and rehabilitation that should follow psychosurgery.

Freeman also warned patients’ families and other caregivers in a less sophisticated way about the need to take into account the possible return of patients to a childhood phase, advising a tolerant and benevolent attitude and, if necessary, a slap, from time to time. With this new doctrine, the collateral effects of leucotomy and lobotomy were to be considered not just normal but even essential to the curing process.

Are there any similarities between the rhetoric apparatus of old and new psychosurgery? It could be an interesting question from a civic discourse point of view. As the unfounded optimism of the first wave of psychosurgery was not contradicted by a sufficiently strong and efficient interpellation, the civic discourse could now be more attentive in order to disclose enough information about the new trends. In fact, if with the emergence of DBS the landscape seems to have changed, as the thousands of videos on Youtube of patients with Parkinson's disease, before and after stimulation show, and the general awareness about the efficiency of DBS applied to movement diseases, the subjective side effects cannot be observed as simply. However, given the trend to apply stimulation techniques to mental troubles, the enthusiasm should be moderated by the difficulty to exhibit good results.

Videos showing patients with and without activated neuromodulation are so impressive that we would not dare to deny something extraordinary is happening before our eyes, just such as patients themselves witness. However, we are not as informed about the long monitoring periods of patients, the emergence of complications, the sustainability of these wonderful effects, side effects, and other psychological aspects of the adaptation of the new status of stimulated patients.

Ultimately, there is not much information about what we cannot see immediately in promotional videos. In fact what we see is the successful side of a treatment that has other unknown aspects, drawbacks and collateral effects. We need to be equally informed about the durability of what is showed, the side effects and patients’ adaptation to their new status as a stimulated human being.

Marc Lévèque, Edgar Durand and Alexander G. Weil, in a letter to the Editor of Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery [8], quoted an article on the implementation of ablative psychosurgery in addiction [9], denouncing, among other malpractices, the revival of the old trichotomy that Moniz and Freeman adopted to classify leucotomy and lobotomy results. Lévèque and accompanying authors do criticize this technical recycling, although we should add it was subject of an interesting adaptation. From the terminology “Good, Fair and Poor” used by Freeman and others, the adaptation, inspired by old psychosurgery, presents however slight differences: “Good” is replaced by “Excellent” and “Fair” is replaced by “Good”, leaving the category “Poor” unchanged (Fig. 2). Lévèque and the coauthors of the referred article also reported other distortions of scientific accuracy and ethical prudence detected by them in the mentioned study. This shows us that there are still practitioners of psychosurgery that, deliberately or not, refine rhetorical models of the past, applying them to very recent studies, and dragging along some ambiguities inherent to the old psychosurgery models (Fig. 2).

Furthermore, it is not uncommon to see published results lacking specification about the degree of success, the variation in postoperative assessment and follow-up information. All that we can retain sometimes is that the postoperative changes are allegedly positive and satisfying, at least immediately. This poses serious problems for the interested public (all of us eager for an informed, critical civic discourse). Certainly we must not judge the past as isolated from the present day. The same criterion applies to judgments of the present when contextual data are missing to understand more precisely the entire framework of what has really changed between old and new psychosurgery.

3 Conclusion

After a long period of moderated practice of ablative psychosurgery, DBS caused a new boom, at first following the impressive results obtained in the treatment of Parkinson disease, then in applying a similar technique to obsessive compulsive disorder and to the syndrome of Gilles de la Tourette. At the same time, the widening of the method to major depression, obesity and chronic pain was envisaged and object of experimental trials. Step by step, new psychosurgery overrode the historical field of the application left by old psychosurgery. In this new wave, the former psychosurgery, based above all on the lesion of neural circuits, was surpassed by the new formula, proclaiming its reversible (or almost reversible) effects.

The world functions so that the socio and geopolitical divide already known in the distribution of other goods seems to result in a more sophisticated treatment for the rich, and a more traditional one for the poor, ablative to disempowered people, neuromodulation for those who can afford it. In reality, both reversible and irreversible techniques are being practiced around the world, generally admitted and justified. There is some evidence showing that DBS being more expensive than the previous lesion techniques, it is not accessible for most patients, forcing the majority to be treated with the irreversible old method.

The most common expressions used when presenting the results continue to be that they are encouraging, promising and satisfactory. If we read again the proceedings of the first International Conference on Psychosurgery, held in Lisbon in 1948, we will find exceptional similarities between old and new adjectivization.

History assembles both present and future, for us as well as for psychosurgery practitioners. They, as well as us, within the recorded data blur the lines between not only what happens in fact, but also what they found logical or just hopeful for the future.

The theoretical vacuum – now more populated with interesting and contradictory hypotheses – beyond the ventriloquism trend, implied and always imply another consequence. Given the lack of predictive potential, each surgery was, and to some extent still is, highly experimental. The systematic use of stimulation to detect the more accurate target for lesion proves it. This fact reveals a difficult separation between experimental and therapeutic acts turning each surgery in a renewed experiment. It also raises the issue of whether experimental research is also the pretext for therapeutic treatments.

Looking into the old psychosurgery, many authors point to the ethical, critical and theoretical deficit. The right and duty of proceeding with scientific experiments, aimed to acquire better knowledge on the nervous system, as far as some held, have not been conditioned by acute criticism and open debate about exaggerations and abuses. Nowadays, under new conditions and in a different context, critic reflections and civic attention would never be too much.

As Marc Lévèque called to our attention, we are yet to find in the specialized literature examples of a lack of independence in the evaluation of results (when the assessment is conducted by members of the same team who operated); short follow-up after surgery (less than one year, for example); non appliance of in-depth tests accounting for which changes were noticed after surgery; and insufficient description of procedures and reasons that lead to choose a precise target.

In face of the enthusiasm surrounding new psychosurgery, one can ask oneself if this is not only the tip of the iceberg.

Disclosure of interest

The author declares that he has no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgements

This text is based on a previous communication presented to the “Université Libre de Bruxelles” 2014 colloquium “Biologie et devenir de l’homme”. Special thanks are addressed to Jean-Noël Missa for his kind invitation. I am also indebted to Lucy Adamson and Joana Correia for their precious assistance in establishing the final English version.

1 These conclusions are based on the analysis of the archives of the Surgery Unit of Hospital Júlio de Matos, Lisboa, inaugurated in 1947, as well as on several criticisms published in Anais Portugueses de Psiquiatria, published by the board of directors of the same institution.

2 For the Belgian case, see Jean-Noël Missa, Naissance de la psychiatrie biologique, Paris, PUF, 2006, pp. 217–236.

3 The Commission finds that there is at least tentative evidence that some forms of psychosurgery can be of significant therapeutic value in the treatment of certain disorders or in the relief of certain symptoms. Because of this finding and the belief that the misuse of psychosurgery can be prevented by appropriate safeguards, the Commission has not recommended a ban on psychosurgery.