1 Abbreviations

cART

combination antiretroviral therapy

PIprotease inhibitor

sdLDLsmall-dense low-density lipoprotein particles

LDLlow-density lipoprotein

SR-B1scavenger receptor B1

ABCG1ATP-binding cassette transporter A1

D0baseline

D45day 45

2 Introduction

HIV-1 infection and its treatment by protease inhibitors (PIs), especially when boosted with ritonavir, have been associated with increased cardiovascular risk [1–3]. This increased risk is partially related to metabolic disorders, including dyslipidemia as hypertriglyceridemia and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) level [4], with a high prevalence of atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype and endothelial dysfunction [2,4]. Clinical studies suggested that cardioprotective properties were more associated with HDL2 than with HDL3, and low levels of HDL2b associated with elevated HDL3b were related to a high cardiovascular risk [5–7].

Many studies reported the role of the HIV-1 infection in addition to the role of PIs-containing combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) in accentuating the atherogenic profile in HIV-infected individuals, which is characterized by a low level of HDL-cholesterol and a high proportion of small-dense low-density lipoprotein particles (sdLDL) [8–10]. Mature HDL can be separated by gradient gel electrophoresis into five distinct subclasses of different sizes: HDL2b (12.9–9.71 nm), HDL2a (9.71–8.77 nm), HDL3a (8.77–8.17 nm), HDL3b (8.17–7.76 nm), and HDL3c (7.76–7.21 nm) [5,11,12]. The largest HDL2b and HDL2a subfractions displayed a superior capacity to mediate cellular free-cholesterol efflux via both scavenger receptor class B1 (SR-BI)- and ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 (ABCG1)-dependent pathways than smaller HDL3 subspecies [13]. HDL3c may provide potent protection of LDL from oxidative damage induced by oxygen reactive species in the arterial intima, resulting in the inhibition of the generation of pro-inflammatory oxidized lipids [14].

In a substudy of the randomized multicenter French National Agency for AIDS and Viral Hepatitis Research (ANRS) 126 VIHstatine trial, we evaluated the effect of 45 days of rosuvastatin (10 mg/day) vs. pravastatin (40 mg/day) on the LDL size and the distribution of LDL-subfractions [10]. We concluded that rosuvastatin was more effective than pravastatin in increasing the diameter of the LDL peak, in decreasing the percentage of atherogenic small-dense LDL and increasing the percentage of less atherogenic large LDL [10].

In the current substudy, our aim was to evaluate the distribution of HDL subfractions at baseline in the same population of HIV-1-infected individuals receiving PIs [1,2,10], to appreciate the effect of a 45-day statin treatment on this distribution, and to compare with the distribution of HDL subfractions in a control population.

3 Materials and methods

Determination of lipid parameters by routine enzymatic methods was performed on fresh sera at baseline (D0) and day-45 (D45) in a central laboratory [1,2]. HDL subclasses were determined blindly of sampling time (D0 versus D45) or treatment arm (rosuvastatin versus pravastatin) in serum, as explained previously, after isolation of lipoproteins by sequential ultracentrifugation [10,15]. The lipoproteins from D0 and D45 of statin treatment were run simultaneously on the same gel, together with lipoproteins isolated from a normolipidemic subject taken as control [2,10].

Seventy-four patients of the 83 patients enrolled in the VIHstatine trial with available frozen samples at baseline and D45 were eligible for this substudy: 36 in the pravastatin arm and 38 in the rosuvastatin arm with the same demographic, immunovirological and lipid parameters, particularly HDL-cholesterol [1,2,10]. Comparisons between the two statin arms or between the two statin arm combined versus 63 healthy normolipidemic controls were analysed using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test, while comparisons between D45 and D0 were analysed using the paired Wilcoxon test.

4 Results

After 45 days, no significant difference was observed between the two arms of statin treatment regarding the distribution of different HDL subclasses percentage, respectively: HDL2a, HDL2b, HDL3a, and HDL3b.

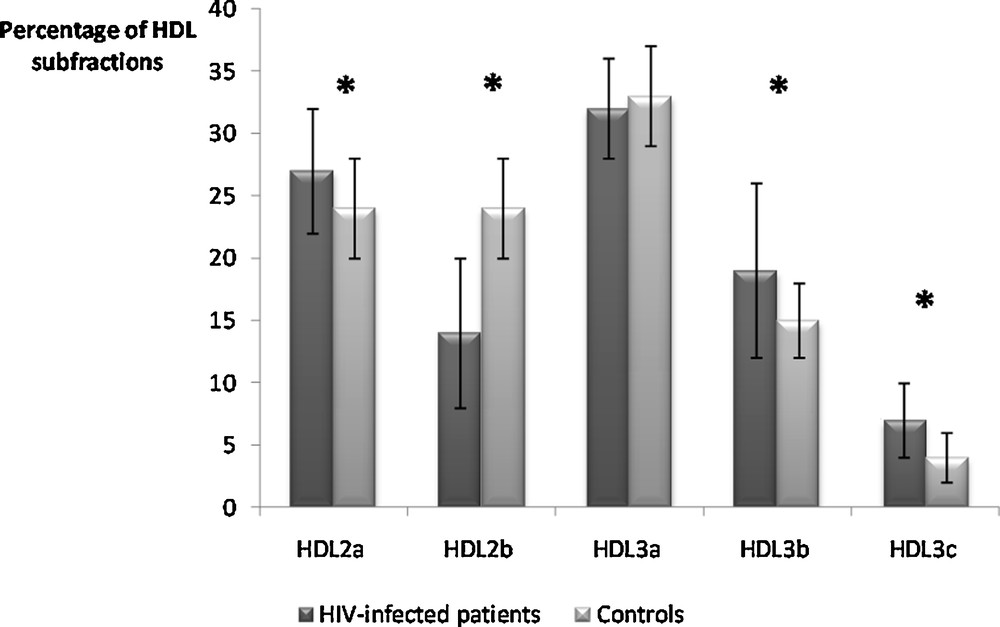

Further analyses were thus performed considering a global statin group (Table 1). After 45 days of statin treatment, only HDL3b subfraction was decreased compared to baseline (P = 0.003). The D45 HDL subfractions in the HIV-infected individuals, compared to those in healthy controls, showed a significantly lower HDL2b proportion (P < 0.001) and significantly higher proportions of HDL2a and HDL3b, while no difference was evidenced for the HDL3a subfraction (Fig. 1).

Distribution of HDL subfraction proportions in the statin-treated HIV-infected patients (n = 74) and in healthy normolipidemic controls (n = 63).

| % | Day 0 (n = 74) |

Day 45 (n = 74) |

Δ (D45 − D0) | P | Healthy controls n = 63 |

P* |

| HDL 2a | 26.90 ± 5.51 | 27.30 ± 5.45 | 0.49 ± 3.74 | 0.159 | 23.87 ± 3.99 | < 0.001 |

| HDL 2b | 13.30 ± 6.15 | 13.50 ± 6.10 | 0.19 ± 3.63 | 0.446 | 23.68 ± 3.62 | < 0.001 |

| HDL 3a | 31.50 ± 3.70 | 32.20 ± 4.35 | 0.69 ± 3.22 | 0.070 | 33.14 ± 4.22 | 0.164 |

| HDL 3b | 20.85 ± 6.80 | 19.50 ± 6.65 | −1.36 ± 4.75 | 0.003 | 15.05 ± 3.40 | < 0.001 |

Percentages of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) subfractions in the global statin-treated HIV-infected group of patients at D45 compared to healthy normolipidemic subjects. * P < 0.001.

5 Discussion

The low levels of HDL2b associated with high levels of HDL3b observed in our study are associated with cardiac heart disease in the general population [5,15]. Furthermore, HDL2b subclass is strongly inversely correlated with the coronary disease risk [16].

Dyslipidemia is a frequent side effect of cART, especially when boosted PIs are used [1]. The lipid disorders are more severe than before cART including PIs use, and usually consist of hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, elevated levels of small-dense LDL particles. Stein et al. [9] reported high proportion of small, less protective HDL particles associated with endothelial dysfunction in a group of 22 HIV-1 patients receiving ART under PIs with stable doses for more than 6 months. Use of PIs in HIV-1 population has been associated with endothelial dysfunction, an early step in atherosclerosis that predicts future adverse cardiovascular events [17] and cardiovascular disease remained increased when compared to the general population [18].

Statins can reduce total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol in patients with HIV-1 infection under PIs, improve endothelial function and delay the progression of cardiovascular disease, while more side effects were observed during statin treatment [18]. Selection of statin treatment and the potential for drug interactions with antiretroviral therapy must be considered in this infected population [18,19].

Only a few studies compared the effect of statins on the distribution of HDL subfractions in dyslipidemic and in control subjects, and their results are contradictory. No data is currently available in HIV-1 patients. Schaefer et al. [16] found that atorvastatin increased the percentage of HDL2b by 25%, whereas those of medium and small HDL3 (i.e. HDL3b and HDL3c) did not significantly change. Harangi et al. [20] reported that atorvastatin significantly increased the proportion of HDL3, whereas HDL2a and HDL2b were decreased in patients receiving 20 mg per day during three months. Lower doses of atorvastatin used in this study could not restore the physiologic proportions of the HDL subclasses. The important anti-atherogenic functions of HDL subclasses include removal of excess cholesterol from peripheral tissues and reverse cholesterol transport to the liver for excretion into bile [5,14].

In conclusion, our study shows no difference in HDL distribution change between pravastatin and rosuvastatin after 45 days treatment, in HIV-1-infected individuals under PIs and only HDL3b subfraction decreased compared to baseline. Nevertheless, when compared to healthy subjects, HDL distribution is clearly different, with a distribution in HIV-1-infected individuals under PIs associated with an increased cardiovascular risk. Reducing atherogenic lipoprotein changes and endothelial dysfunction in HIV under PIs, by optimal statins and management of cardiovascular risk, is needed in this population. However, the lack of power of our study (respective power for each of the four tested variables i.e. HDL2a, HDL2b, HDL3a, and HDL3b: 20%, 7%, 45%, and 65%, respectively) could explain the negative results and constitutes a limitation. Interactions with cART should also be considered. Finally, these results need to be confirmed on a large number of HIV-1-infected patients.

Authors’ contributions

Recruitment of patients was carried out by: E.A., M.-A.V., P.G., O.K., and the ANRS 126 study group.

Statistical analysis was performed by: L.A., D.C., P.G.

Measurement of lipid parameters, and HDL distribution was done by: M.-C.F., C.C., R.B., D.B-R.

Interpretation of biological data was performed by: R.B., D.B-R.

Drafting of the article was performed by: R.B., D.B-R., E.A, P.G., D.C.

Study design, analysis and interpretation of the data, and critical revision of the article for important intellectual content and final approval of the article was done by: R.B., D.B-R., E.A., P.G., D.C., L.A., M.-A.V., O.K.

Disclosure of interest

Lambert Assoumou, Dominique Bonnefont-Rousselot and Olga Kalmykova declare that they have no competing interest. Randa Bittar has received travelling grants, payment of registration fees and lecture fees from Gilead Sciences and Solvay. Philippe Giral has received lecture fees from Pfizer, AstraZeneca and Solvay and travel grants from Merck. Élisabeth Aslangul has received travel grants from Sanofi Aventis, Pfizer and Bristol-Myers-Squibb. Marc-Antoine Valantin has received lecture fees, traveling expenses and payment of registration fees from Roche, Tibotec (Johnson & Johnson), Gilead, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, MSD, and Boehringer-Ingelheim. Dominique Costagliola has received travel grants, consultancy fees, honoraria or study grants from various pharmaceutical companies, including Abbott, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Janssen, Merck, Roche.

Acknowledgements

The French National Agency for AIDS and Viral Hepatitis Research (ANRS) sponsored the trial and was involved in the study design.

This work was presented at the 82nd European Atherosclerosis Society Congress, 31 May–3 June 2014, Madrid, Spain, as a poster presentation (Abstract EAS-1175).