1 Introduction

Sex steroid hormones are mainly synthesized within reproductive organs and once secreted they regulate different physiological events in target tissues. In the testis, they are primarily produced in specialized cells, the Leydig and Sertoli cells, where they are synthesized from a common precursor, cholesterol, via a series of enzyme-catalyzed reactions [1]. On the other hand, the possibility exists that sex hormone synthesis occurs also in germ cells [2,4]. The steroidogenic pathway begins in mitochondria, where cholesterol is converted into pregnenolone by the cytochrome P450 side-chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc); in such event, the Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory (StAR) protein is required to shut cholesterol cross the mitochondrial membrane [5]. Then, pregnenolone is metabolized to dehydroepiandrosterone in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum, where its modification into androstenedione is due to 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD); later, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD) catalyzes the transformation of androstenedione to testosterone (T). Finally, testosterone can be converted both into 17β-estradiol (E2) by cytochrome P450 aromatase or in 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by 5α-reductase (5α-Red) [1,2,6,8].

The localization of steroidogenic enzymes has been determined in mammalian testes, where it has been highlighted that their expression and localization change according to the reproductive strategy [9,10,11]. In contrast, few investigations are available concerning gene expression and/or localization of steroid-synthesizing enzymes in reptiles [12,13]. In fact, the most information concerns amphibians, for example in Pelophylax esculentus, has been shown that cyclic endocrine testis activity could be regulated by the up-regulation of the expression of the steroidogenic enzyme genes, and the higher levels of 3β-HSD, 17β-HSD, P450 aromatase and 5α-Red mRNA have been found during the post-reproductive period. In addition, in Pelophylax esculentus testis, it is known that StAR, P450 aromatase and 5α-Red expression could be regulated by d-aspartate activity [14,15]. However, it is generally known that sex steroids play a crucial role in the testis, regulating the reproductive processes throughout either the promotion of spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis (for example acrosome biogenesis) or the development/differentiation and the maintenance of secondary sex characteristics in all vertebrates, particularly those with seasonal reproductive cycle, such as P. sicula [2,16,18]. In the lizard, Podarcis sicula, we have previously demonstrated a different expression and localization of P450 aromatase during the spermatogenic cycle, strongly suggesting that P450 aromatase activity is under the control of Pituitary Adenylate Cyclase Activating Peptide (PACAP) [19] and Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP) [20]. These investigations have showed that PACAP and VIP could infer with the 17β-estradiol levels, causing subsequent modification of circulating 17β-estradiol levels.

The aim of the present investigation was to assess new information about the occurrence and the localization of different steroidogenic enzymes (StAR, 3β-HSD, 17β-HSD, 5α-Red) that could be involved in the endocrine regulation of the spermatogenic cycle of Podarcis sicula. This investigation was carried out in three different periods of the spermatogenic cycle: summer stasis (July–August), autumnal resumption (November) and reproductive period (May–June). The stasis period is the moment of testicular activity blocking, when the seminiferous tubules are composed only by spermatogonia and Sertoli cells, an organization similar to that reported in immature rats [2]. The autumnal resumption is characterized by a recovery of spermatogenesis, so the seminiferous tubules are composed by spermatogonia, spermatocytes I, spermatocytes II, spermatids and few spermatozoa, that are unavailable for fertilization. Finally, the reproductive period is the mating time and the tubules consist of all differentiating germ cells, as well as numerous spermatozoa, ready for ejaculation and subsequent fertilization [16].

Using immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry, we demonstrated that all steroidogenic enzymes here analyzed are widely localized both in somatic and germ cells during the different phases of the Podarcis spermatogenic cycle, in agreement with changes of sex hormone levels recorded during the reproductive cycle [4].

2 Materials and methods

Sexually mature males of P. sicula were collected in Campania (southern Italy; latitude: 41°19’54“N; longitude: 13°59’29”E) during the summer stasis (July 2013), the autumnal resumption (November 2013) and the reproductive period (May 2013). Once collected, the animals were maintained in a soil-filled terrarium and fed ad libitum with Tenebrio molitor larvae, for approximately 15 days, the time required to recover from the capture stress. The experiments were approved by institutional committees (Ministry of Health of the Italian Government) and organized to minimize the number of animals utilized in the experiments. The animals were killed by decapitation after deep anesthesia with ketamine hydrochloride (325 pg·g−1 body mass; Parke-Davis, Berlin, Germany). The sexual maturity of each animal was determined by morphological parameters and histological analysis [21,25]. Three animals were used for each phase of the reproductive cycle considered.

2.1 Immunoblot

In the first instance, antibody specificity was tested performing an immunoblot analysis on Podarcis sicula testicular proteins, as previously reported by Prisco et al. (2017) [3]. Briefly, 30 μg of testicular proteins extract were loaded onto 12% SDS-PAGE; after electrophoresis, one gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue, while another was used for Western Blot analysis. For antigen detection purposes, assays were performed using rabbit anti-human StAR, rabbit anti-human-3β-HSD, rabbit anti-mouse-17β-HSD and mouse anti-human-5α-Red antibodies. All antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA. Antibodies were diluted at 1:100, except for anti-StAR, which was diluted at 1:500, in 3% BSA in Tris-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and the reaction was revealed with a biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit/mouse secondary antibody and an avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC immune peroxidase kit, Pierce), using DAB (Sigma-Aldrich) as a chromogen. Negative controls were performed by omitting primary antibodies. The immunoblot was performed on samples of the reproductive period.

2.2 Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry, 5-μm-thick sections of Bouin fixed testis on poly-l-lysine slides have been treated as previously reported [26,31]. Briefly, the sections were treated with 10 mM citrate buffer pH 6.0 and then incubated in 2.5% H2O2. The non-specific background was reduced with the incubation in normal goat serum (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for1 h at room temperature. The sections were then treated overnight at 4 °C with primary rabbit antibodies diluted in normal goat serum:

- • rabbit anti-human StAR (1:500);

- • rabbit anti-human 3β-HSD (1:50);

- • rabbit anti-mouse 17β-HSD (1:50);

- • mouse anti-human 5α-Red (1:100).

The reaction was revealed with a biotin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit/mouse secondary antibody and an avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC immune peroxidase kit, Pierce), using DAB (Sigma-Aldrich) as the chromogen. Negative controls were carried out by omitting primary antibodies. The immunohistochemical signal was observed using a Zeiss Axioskop microscope; the images were acquired using AxioVision 4.7 software (Zeiss).

3 Results

3.1 Western blot for StAR, 3β-HSD, 17β-HSD and 5α-Red

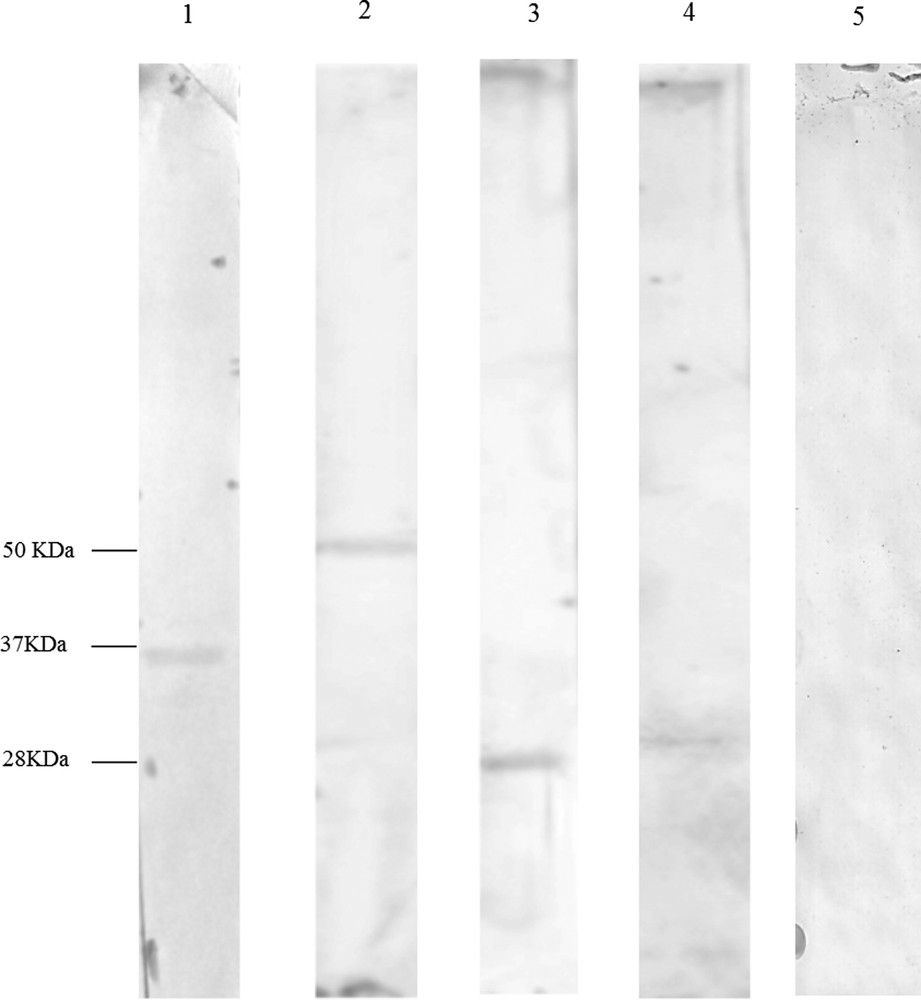

StAR antiserum detected only one band of molecular mass of about 37 kDa (Fig. 1, Lane 1), 3β-HSD antiserum one band of molecular mass about 50 kDa (Fig. 1, Lane 2), 17β-HSD antibody one band of about molecular mass 28 kDa (Fig. 1, Lane 3) as well as 5α-Red antibody (Fig. 1, Lane 4). No positive reaction was observed when the primary antibody for each enzyme was omitted (Fig. 1, Lane 5).

Western blot for StAR, 3β-HSD, 17β-HSD and 5α-Red in Podarcis sicula testis during the reproductive period; protein ladder on nitrocellulose membrane. Lane 1: the band of 37 kDa corresponds to StAR; lane 2: the band of 50 kDa corresponds to 3β-HSD; lane 3: the band of 28 kDa corresponds to 17β-HSD; lane 4: the band of 28 kDa corresponds to 5α-Red. Lane 5: no signal is evident in the control.

3.2 Immunohistochemistry for StAR

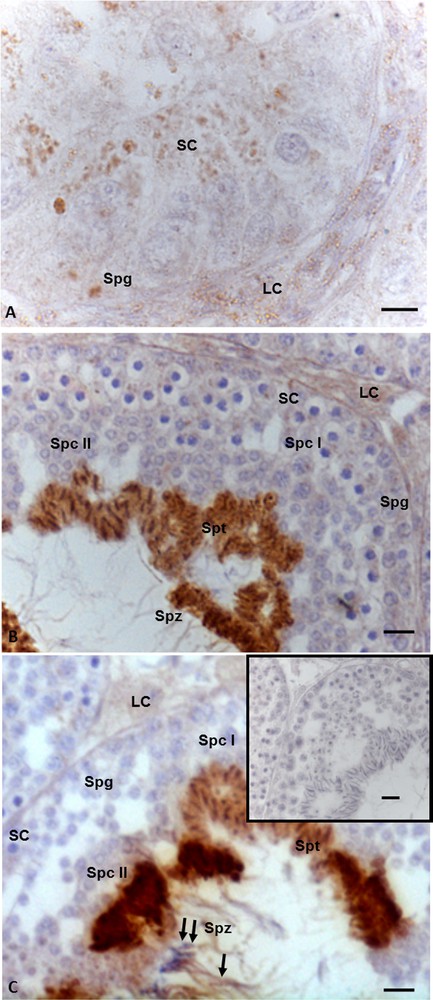

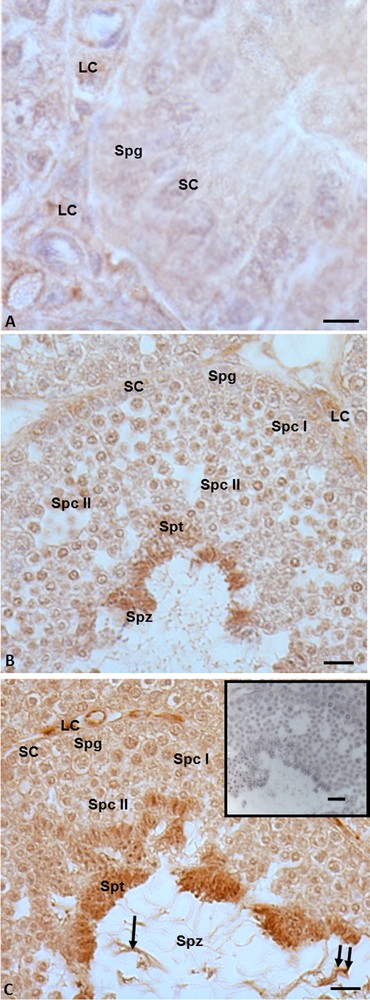

StAR immunohistochemistry highlighted that this protein is widely distributed both in somatic and germ cells in all three investigated phases of the spermatogenic cycle. In details, during the summer stasis, the signal was recorded in spermatogonia and in Leydig and Sertoli cells (Fig. 2A). During the autumnal resumption (Fig. 2B) and in the reproductive period (Fig. 2C), the signal showed the same localization but a different intensity: faint in spermatogonia, spermatocytes I and II, as well as in Leydig and Sertoli cells, strong in spermatids and spermatozoa (Fig. 2B, C). Furthermore, in the reproductive period, the signal was evident also in the head and tail of spermatozoa (Fig. 2C). No immunohistochemical signal was found in the control sections (Fig. 2C, insert).

Immunohistochemical localization (brown areas) of StAR. A. Summer stasis. The signal is evident in spermatogonia (Spg) and in Sertoli (SC) and Leydig (LC) cells. B. Autumnal resumption. A strong signal is evident in the heads of spermatids (Spt), and spermatozoa (Spz); a faint signal occurs in spermatogonia (Spg), spermatocytes I (Spc I) and II (Spc II), as well as Leydig (LC) and in Sertoli cells (SC). C. Reproductive period. The signal is notably evident in spermatids (Spt), and spermatozoa (Spz), at level of head (double arrow) and tail (arrow) as well as in Leydig (LC) and Sertoli (SC) cells, a faint signal occurs in spermatogonia (Spg) spermatocytes I (Spc I) and II (Spc II). Insert C: no signal is present in control sections. The scale bars correspond to 5 μm in Fig. A, 10 μm in Fig. B and C and 20 μm in the insert in Fig. C. Masquer

Immunohistochemical localization (brown areas) of StAR. A. Summer stasis. The signal is evident in spermatogonia (Spg) and in Sertoli (SC) and Leydig (LC) cells. B. Autumnal resumption. A strong signal is evident in the heads of spermatids (Spt), and spermatozoa (Spz); a ... Lire la suite

3.3 Immunohistochemistry for 3β-HSD

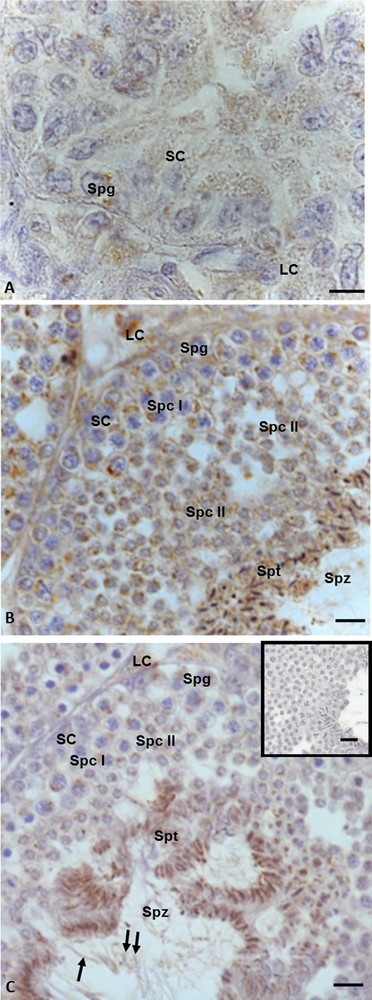

Immunopositivity for 3β-HSD was recorded both in somatic and germ cells in all three phases of the spermatogenic cycle. In the summer stasis, a faint signal was evident in spermatogonia and in the cytoplasm of Sertoli and Leydig cells (Fig. 3A). In the autumnal resumption (Fig. 3B), as well as in the reproductive period (Fig. 3C), the immunohistochemical signal was evident in germ cells (spermatogonia, spermatocytes I and II, spermatids and spermatozoa) as well as in Leydig and Sertoli cells (Figs. 3B, C) with a different intensity, which, as previously reported, was recorded in spermatid and spermatozoa. Furthermore, in the reproductive period, the signal was evident also in the head and tail of spermatozoa (Fig. 3C). No immunohistochemical signal was found in the control sections (Fig. 3C, insert).

Immunohistochemical localization (brown areas) of 3β-HSD. A. Summer stasis. The signal is evident in Sertoli (SC) and Leydig (LC) cells and spermatogonia (Spg). B. Autumnal resumption. The signal is evident in Leydig (LC) and Sertoli cells (SC), spermatogonia (Spg), spermatocytes I (Spc I) and II (Spc II), spermatids (Spt) and spermatozoa (Spz). C. Reproductive period. The signal is evident in Leydig (LC) and Sertoli (SC) cells, spermatogonia (Spg), spermatocytes I (Spc I) and II (Spc II), spermatids (Spt), as well as heads (double arrow) and tails (arrow) of spermatozoa (Spz). C (insert): No signal is present in control sections. The scale bars correspond to 5 μm in Fig. A, 10 μm in Fig. B and C and 20 μm in the insert in Fig. F. Masquer

Immunohistochemical localization (brown areas) of 3β-HSD. A. Summer stasis. The signal is evident in Sertoli (SC) and Leydig (LC) cells and spermatogonia (Spg). B. Autumnal resumption. The signal is evident in Leydig (LC) and Sertoli cells (SC), spermatogonia (Spg), spermatocytes I (Spc ... Lire la suite

3.4 Immunohistochemistry for 17β-HSD

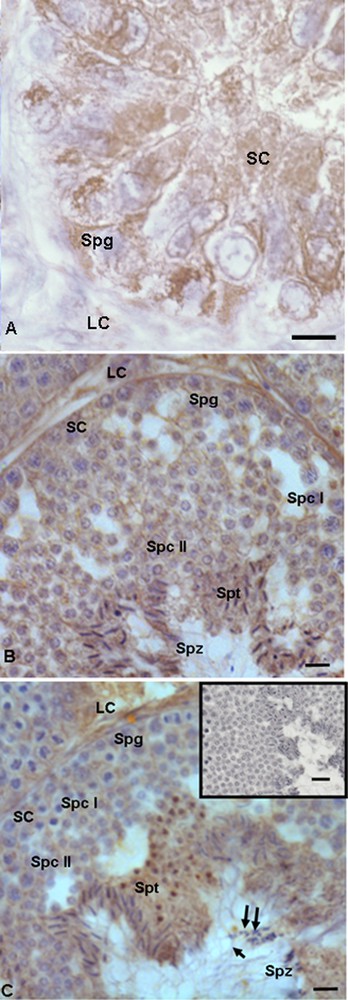

In the summer stasis, a strong immunopositive signal for 17β-HSD was recorded both in spermatogonia and in Sertoli cells (Fig. 4A), whereas a faint signal was evident in Leydig cells (Fig. 4A). In the autumnal resumption (Fig. 4B), as well as in reproductive period (Fig. 4C), the spermatogonia, spermatocytes I and II, as well as Leydig and Sertoli cells were faintly labeled, whereas spermatids and spermatozoa were strongly labelled) (Figs. 4B, C). In addition, in the reproductive period, the signal was evident also in the head and the tail of spermatozoa (Fig. 4C). No immunohistochemical signal was found in the control sections (Fig. 4C, insert).

Immunohistochemical localization (brown areas) of 17β-HSD. A. Summer stasis. The signal is quite strong in Sertoli (SC) and Leydig (LC) cells, as well as in spermatogonia (Spg). B. Autumnal resumption. The signal is evident in Sertoli (SC) cells, spermatogonia (Spg), spermatocytes I (Spc I) and II (Spc II), as well as in Leydig (LC), spermatids (Spt) and spermatozoa (Spz), where it is notably strong. C. Reproductive period. Signal shows the same localization and intensity: faint is evident in spermatozoa (Spz) and Sertoli (SC) cells, spermatogonia (Spg), spermatocytes I (Spc I) and II (Spc II), strong in Leydig (LC), spermatids (Spt) and spermatozoa (Spz); spermatozoa in the lumen were labelled at the level of the head (double arrow) and the tail (arrow). C (insert): No signal is present in control sections. The scale bars correspond to 5 μm in Fig. A, 10 μm in Fig. B and C and 20 μm in the insert of Fig. C. Masquer

Immunohistochemical localization (brown areas) of 17β-HSD. A. Summer stasis. The signal is quite strong in Sertoli (SC) and Leydig (LC) cells, as well as in spermatogonia (Spg). B. Autumnal resumption. The signal is evident in Sertoli (SC) cells, spermatogonia (Spg), spermatocytes I ... Lire la suite

3.5 Immunohistochemistry for 5α-reductase

Immunohistochemistry performed with anti-5α-reductase antibody highlighted that in the summer stasis, the signal was recorded only in the cytoplasm of Leydig cells (Fig. 5A). No signal was evident in spermatogonia and Sertoli cells (Fig. 5A). In the autumnal resumption, the signal occurred both in germ cells (spermatogonia, spermatocytes I and II, spermatids and spermatozoa) (Fig. 5B) and in somatic cells (Leydig and Sertoli) (Fig. 5B). The same localization and intensity of the signal were recorded in reproductive period: indeed, a strong immunohistochemical signal was evident in mitotic and meiotic germ cells, i.e. spermatogonia, spermatocytes I and II, spermatids, and finally within spermatozoa, at the level of the head and the tail (Fig. 5C), as well as in Leydig and Sertoli cells. No immunohistochemical signal was found in the control sections (Fig. 5C, insert).

Immunohistochemical localization (brown areas) of 5α-reductase. A. Summer stasis. the signal is evident within Leydig (LC) cells. No signal occurs in Sertoli (SC) cells and spermatogonia (Spg). B. Autumnal resumption. The signal is notably evident in Leydig cells (LC), spermatids (Spt) and spermatozoa (Spz). Sertoli (SC) cells, spermatogonia (Spg), spermatocytes I (Spc I) and II (Spc II) highlight a faint signal. C. Reproductive period. The signal occurs quite strong in Leydig (LC), spermatids (Spt), as well as in spermatozoa (Spz) at the level of the head (double arrow) and the tail (arrow); Sertoli (SC) cells, spermatogonia (Spg), spermatocytes I (Spc I) and II (Spc II) highlight a faint signal. C (insert): No signal is present on control sections. The scale bars correspond to 5 μm in Fig. A, 10 μm in Fig. B and C and 20 μm in the insert of Fig. C. Masquer

Immunohistochemical localization (brown areas) of 5α-reductase. A. Summer stasis. the signal is evident within Leydig (LC) cells. No signal occurs in Sertoli (SC) cells and spermatogonia (Spg). B. Autumnal resumption. The signal is notably evident in Leydig cells (LC), spermatids (Spt) and ... Lire la suite

4 Discussion

Spermatogenesis is a complex process that is under the control of the pituitary gonadotropins, [32,33] and local testicular factors including testosterone and 17β-estradiol [2,3,34,36]. In our experimental model, P. sicula, high titers of 17β-estradiol and low titers of testosterone arrest spermatogenesis, whereas low titers of 17β-estradiol and high titers of testosterone induce the resumption of spermatogenesis [4,16,37]. Furthermore, we demonstrated that testicular endocrine activity of P. sicula during the reproductive cycle could also be mediated by d-aspartic acid [38,39]. More recently, we highlighted that the synthesis of testosterone and 17β-estradiol production in P. sicula are under the control of VIP [20] and PACAP [19], two neuropeptides locally synthesized and involved in the control of Podarcis spermatogenesis [21,26,29] and change in relation to the expression and localization of P450 aromatase [4,40]. After validating the antibodies through the Western Blot, with the results of present immuhistochemistry analyses, we have highlighted the localization of all the other enzymes involved in steroidogenesis, i.e. StAR, 3β-HSD, 17β-HSD, 5α-Red in the Podarcis sicula testis. Our immuhistochemistry investigations, performed during significant periods of the spermatogenic cycle (summer stasis, autumnal resumption, and reproductive period) show that all the above-mentioned enzymes are widely present in the testis and that their localization has been evidenced both in somatic and germ cells.

This means that steroidogenesis in the testis of Podarcis sicula could potentially occur both in somatic and germinal cells, in agreement with what has already been highlighted in this system for aromatase [4], and in other models as in mussels [3] and in the rat [2]. Notwithstanding that immunohistochemistry is not a quantitative method, it should be noted that in Podarcis testis the steroidogenic process could be quite relevant during spermiogenesis, i.e. in elongated spermatids and testicular spermatozoa, as our investigations highlighted a quite intense labelling in the head region of these cells. These observations are particularly true for the 5α-Red enzyme; indeed, such enzyme is lacking in germ and Sertoli cells during the summer stasis; by contrast, during the autumnal resumption and the reproductive period, 5α-Red enzyme is well represented. Considering this, it can be hypothesized that in the testis the cholesterol could be locally converted into testosterone during the autumnal resumption and the reproductive period, thanks to the presence in somatic and germ cells of StAR, as well as 3β-HSD and 17β-HSD. Testosterone in turn could be converted into dihydrotestosterone by 5α-Red, the most active form of androgen, also responsible of the activation of mitotic processes and of the spermatogenesis [1]. On the other hand, we have previously reported that during the summer stasis, autumnal resumption and reproductive period, the P450 aromatase is well represented [4]. In particular, P450 aromatase is present during the summer stasis, when StAR is widely represented in all cell types of testis as well as 3β-HSD and 17β-HSD, whereas 5α-Red only occurs in Leydig cells. It should suggest that in the summer stasis the steroidogenic pathway is mainly involved in the 17β-estradiol production, while dihydrotestosterone synthesis is limited to Leydig cells. This hypothesis is also supported by a recent investigation showing that, during the summer stasis in Podarcis sicula testis, the highest titers of both P450 aromatase and 17β-estradiol are recorded together with low titers of testosterone [4]. In this regard, in Podarcis testis it could be hypothesized that the steroidogenic enzymes are engaged as switches on/off of spermatogenesis. In particular, a pivot role in the control of Podarcis spermatogenesis could be played by 5α-Red and P450 aromatase, as the different presence of one of the two enzymes could determine the resumption or the arrest of spermatogenesis. Especially, when the 5α-Red is widely present, the resumption of spermatogenesis takes place thanks to dihydrotestosterone production; by contrast, when P450 aromatase is widespread, the block of spermatogenesis occurs as an effect of massive production of 17β-estradiol. Furthermore, the presence of androgen and estrogen receptors [40] at the level of germ cells in Podarcis testis, strongly suggests that the sex hormones could act in a paracrine and/or autocrine manner. Finally, it is interesting to note that in the reproductive period, both head and tail of spermatozoa are positively immunolabelled for all enzymes analyzed. This data could strongly suggest that the steroidogenic pathway occurring in the testis is beneficial not only for their implication in spermatogenesis, but also for the subsequent phases, including acrosome reaction and motility of spermatozoa.

In conclusion, the present results demonstrate for first time that the key enzymes involved in steroidogenesis for sex hormone production are well represented also in the testis of non-mammalian vertebrates and provide useful information to extend the knowledge of the steroidogenesis control in Podarcis, where somatic and germ cells could be differently involved in local sex hormone production.

Funding

This work was supported by the 'Università degli studi di Napoli Federico II'.