1. Introduction

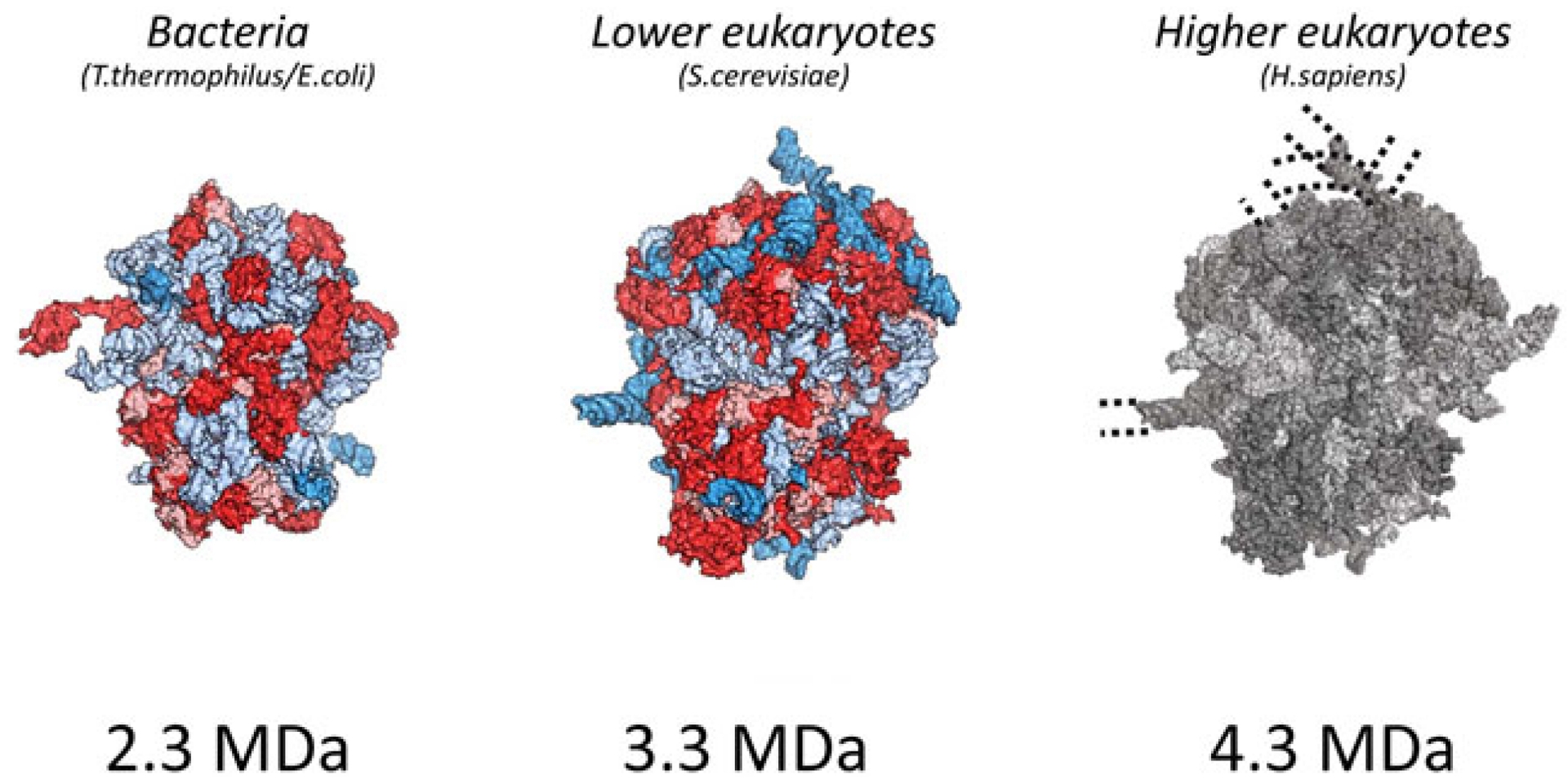

Ribosomes are multi-megadalton cellular machineries constituted of proteins and rRNA in charge of protein biosynthesis. Throughout evolution, ribosomes have increased in size. Expansions occur both at the protein level, with the enlargement of all large ribosomal proteins, and at the RNA level—with the increase in length of ribosomal RNA. The expansions within ribosomal RNA clusters in conserved regions facing the periphery of the ribosome. Recent biochemical and structural studies have shed light on how specific rRNA extension segments (ESs) interact with protein factors during translation. High-resolution crystal structures of bacterial and yeast ribosomes (Figure 1), in combination with more recent cryo-EM analyses, have been crucial in elucidating the fundamental mechanisms of protein synthesis in prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems (Melnikov et al., 2012; Noller, 2024; Jackson et al., 2010). However, after 35 years of ribosome structural studies, there is little structural information about some ribosomal elements such as the L7/L12-stalk (P-stalk for eukaryote), the protein pentameric complex and several rRNA expansion segments (ES) of highly developed organisms (Melnikov et al., 2012; Yusupova and Yusupov, 2017; Nurullina et al., 2024).

Crystal structures of bacteria 70S and yeast 80S ribosomes with molecular weight according to 2.3 and 3.3 MDa. Cryo-EM structure of the human 80S ribosome, as an example of the ribosome from highly developed organisms with a molecular weight of 4.3 MDa.

A genome sequence comparison of ribosomal RNA from different kingdoms indicates an extension of the rRNA as the complexity of the organisms increases (Armache et al., 2010a; Armache et al., 2010b). Among the eukaryotes, the mass of the ribosome varies from 3.3 MDa in unicellular eukaryotes to 4.3 MDa in humans (Figure 1). This difference is mainly due to the enlargement of four specific expansion segments distributed across the rRNA (Hariharan et al., 2023). The expansion segments are generally located at the solvent surface and do not directly interact with ribosome functional sites (Armache et al., 2010a; Taylor et al., 2009; Ben-Shem et al., 2011). Even though the locations of the insertion sites of the expansion segments coincide, their length and nucleotide composition differ among eukaryotes: ESs are generally more GC-rich in vertebrates than in invertebrates and unicellular eukaryotes (Armache et al., 2010a; Armache et al., 2010b).

Structurally, rRNA expansion segments can be divided into two clusters: the first type is known to interact with ribosomal proteins or rRNA, such as ES31L and ES39L (Figure 4); the second type of rRNA ES includes long rRNA helices anchored to the ribosome via their bases. ESs belonging to this group can adopt different conformations, as observed for the flexible ES6S and ES27L, although their functional role is not yet clear (Melnikov et al., 2012). Studies have been carried out to investigate the involvement of ESs in translational fidelity, ribosome biogenesis, and protein folding (Hariharan et al., 2023). ES6S, located in the vicinity of the mRNA entry and exit sites, and ES27L, localized close to the polypeptide exit tunnel, were shown to help translation factors access the ribosome (Shankar et al., 2020; Beckmann et al., 2001). Using systematic deletion experiments of specific ESs, it was shown that almost all ESs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are required and vital for ribosome biogenesis (Ramesh and Woolford, Jr, 2016). Also, it was demonstrated that ES27L and ES7L orchestrate the binding and anchoring of the acetyltransferase NatA complex, which is required for acetylation of the nascent peptide chain and facilitates binding of the conserved enzyme methionine aminopeptidase (MetAP) responsible for cleaving off the N-terminal methionine residue (Knorr et al., 2019; Fujii et al., 2018). Generally, ESs are believed to be involved in many different processes that maintain ribosome efficiency (Hariharan et al., 2023).

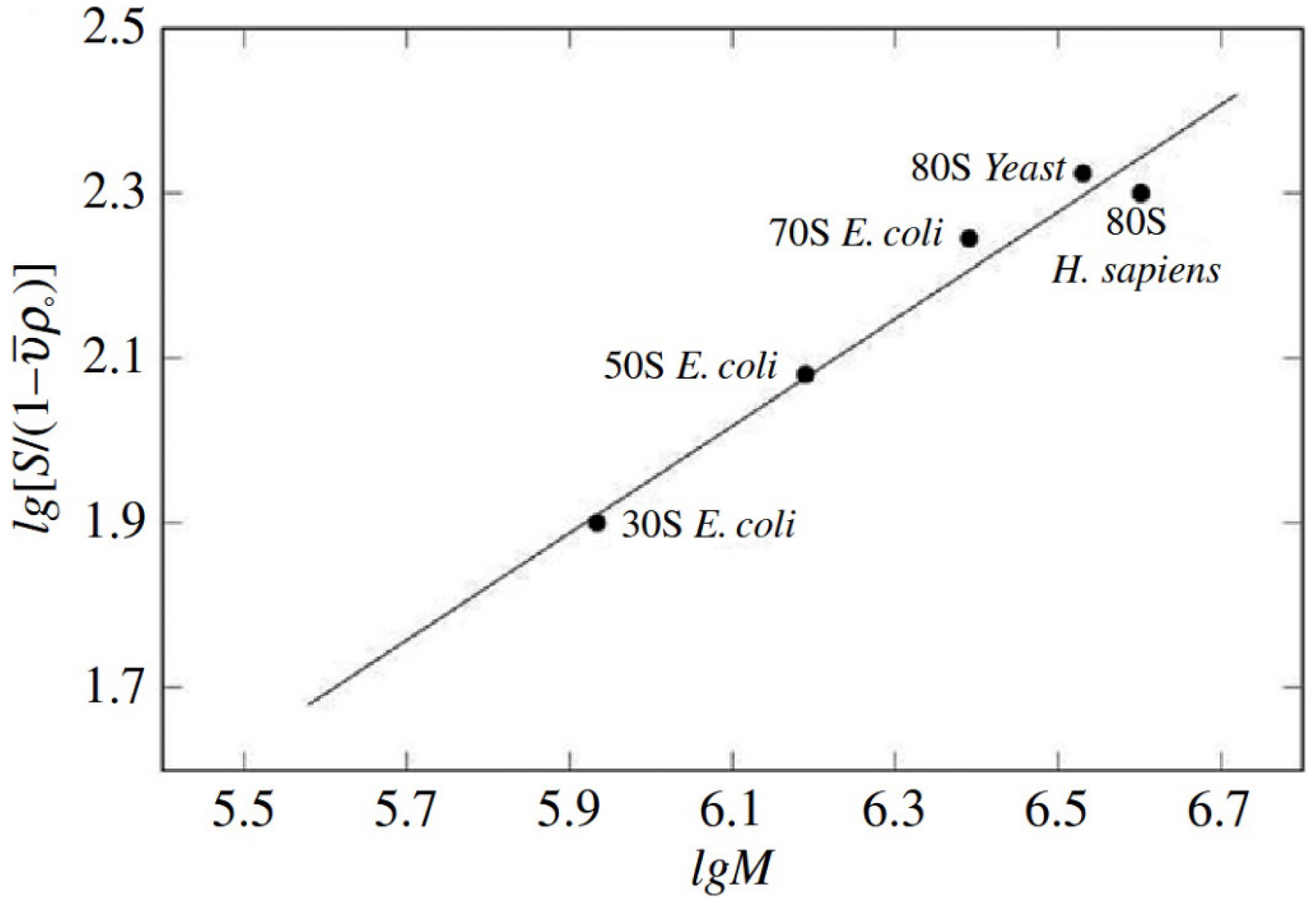

An interesting observation was made while comparing the sedimentation coefficients of bacterial, yeast and human ribosomes. Comparison of the sedimentation coefficients of the bacterial ribosomal 50S and 30S subunits, the bacterial 70S ribosome, the yeast 80S ribosome and the human ribosome showed a partially unfolded structure of the human ribosome. The experimental sedimentation coefficients of the human ribosome and the yeast ribosome were 78S and 80S, respectively (Figure 2). However, the molecular weight of the human ribosome is approximately 1,000,000 Da more than the yeast ribosome owing to the longer expansion segments of the 28S RNA. A partially unfolded structure of the human ribosome expansion segments made the crystallization of this ribosome difficult and made other structure functional studies challenging to accomplish.

Dependence of the sedimentation coefficient of the ribosome particle on molecular weight. Graphic kindly provided by S. Agalarov.

Most studies regarding the function of expansion segments have been carried out in yeast, whose expansion segments are shorter than in mammals (Shankar et al., 2020). The main challenges in answering these enduring questions lie in the different intrinsic limitations of structural techniques, such as the need for crystal growth in crystallography and the limited resolution caused by flexibility and averaging in cryo-EM and cryo-ET. The rRNA expansion segments and protein elements mentioned above are highly flexible and often unstructured, which hinders both proper crystallization—crucial for achieving high-resolution data—and accurate image alignment in cryo-EM and cryo-ET, essential for resolving fine structural details (Armache et al., 2010a; Armache et al., 2010b; Holvec et al., 2024). A successful approach to visualize expansion segments is cryo-ET in situ, which has been used efficiently to resolve ES of Dictyostelium discoideum ribosomes. Despite the low resolution achieved, Hoffmann and collaborators depicted the three-dimensional features of rRNA ES in a near-physiological environment, capturing them in complex with several translation factors. Their structural work supported the long-standing hypothesis behind the role of ES in translation fidelity and its fine-tuning, thus suggesting their transversal role in the evolution of higher eukaryotes (Hoffmann et al., 2022). An alternative way to investigate the structure of these flexible regions involves a more biological rather than technical approach. Starting from functional data, researchers made the hypothesis that some protein factors could lock such regions in a certain conformation, allowing their visualization. It is the case of the maturation protein Arx1, which interacts with ES27L in the pre-60S particles of S. cerevisiae ribosomes. The interaction with Arx1 stabilizes the region, making the ES27L flexible helix a more stable hub for further protein interactions that would lead to the export of the pre-60S ribosomes to the cytosol (Greber et al., 2012).

2. Natural crystals of ribosomes of highly developed organisms

An important observation, made several decades ago, was the identification of ribosome hibernation in Gallus gallus. During study of the hypothermic effects on chicken microtubules, highly ordered bidimensional layers of ribosomes were discovered (Barbieri, 1979a; Barbieri, 1979b; Barbieri, 1979c). Bidimensional layers were studied using electron diffraction techniques, thus demonstrating their crystalline nature, with each unit cell containing four ribosomes—tetramers (Milligan and Unwin, 1986). Tetramers were found and isolated from all tissues of the embryo, demonstrating that under cold exposure chicken ribosomes can exist in various forms: monomeric, tetrameric, and in crystalline layers (Barbieri, 1979b; Milligan and Unwin, 1982). Several questions regarding the formation, the structure and the role of these tetramers and larger aggregates remain unanswered. Due to the compact form of both layers and tetramers, it is easy to think that expansion segments and protein factors might play a role in the formation of ribosomal sheets, by stabilizing ribosomes via rRNA–rRNA and/or rRNA–protein interactions. The study of this phenomenon began in the early 70s, but due to a lack of technical capabilities, no certain results have been obtained.

Ribosome crystalline layers have been found in sand lizard (Lacerta agilis) and common chicken eggs (Gallus gallus) exposed to cold stress (Porte and Zahnd, 1961; Ghiara and Taddei, 1966). We can conclude that this is a physiological response occurring under conditions of stress-induced hypothermia. The ability of the ribosomes from chick embryos to form tetramers and 2-D crystals in situ under stress conditions allows its purification and recrystallization (Milligan and Unwin, 1982). Isolated G. gallus ribosomes could be used for the stabilization and structural study of expansion segments.

3. Gallus gallus ribosomes for structural study. Possible stabilization of expansion segments

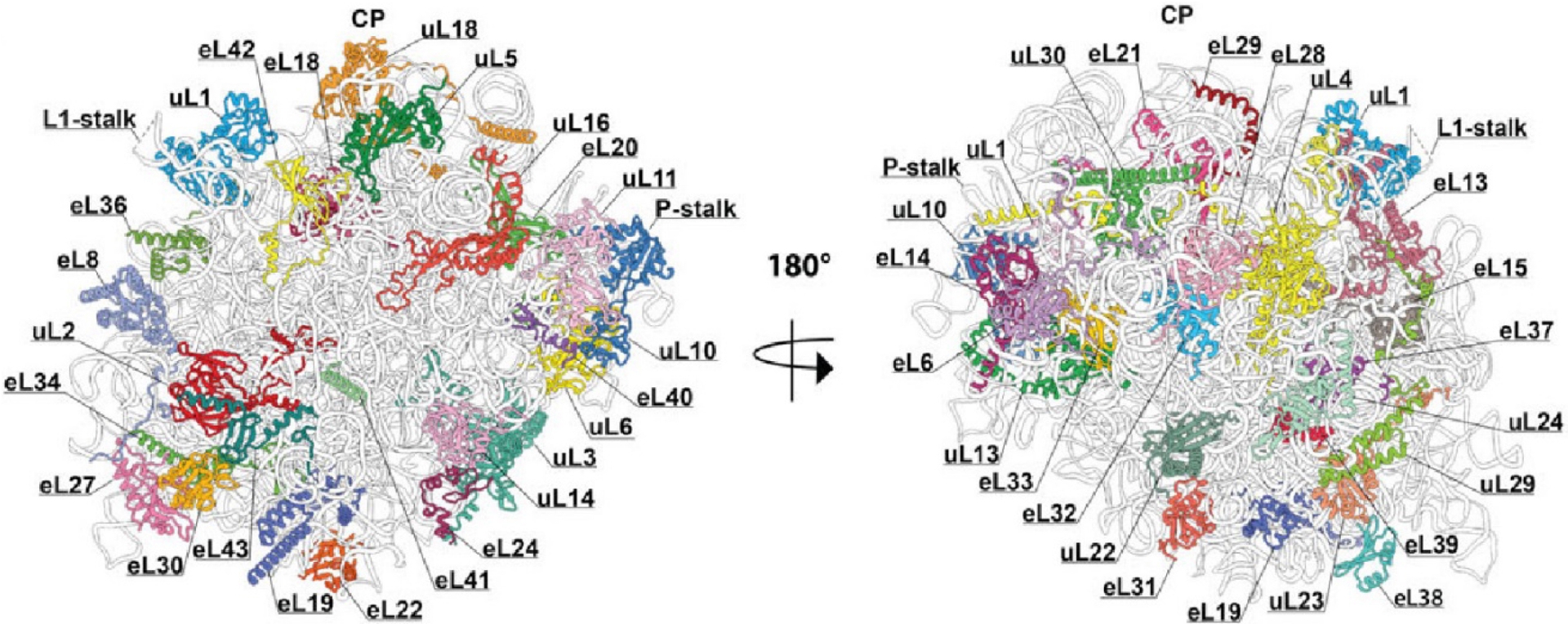

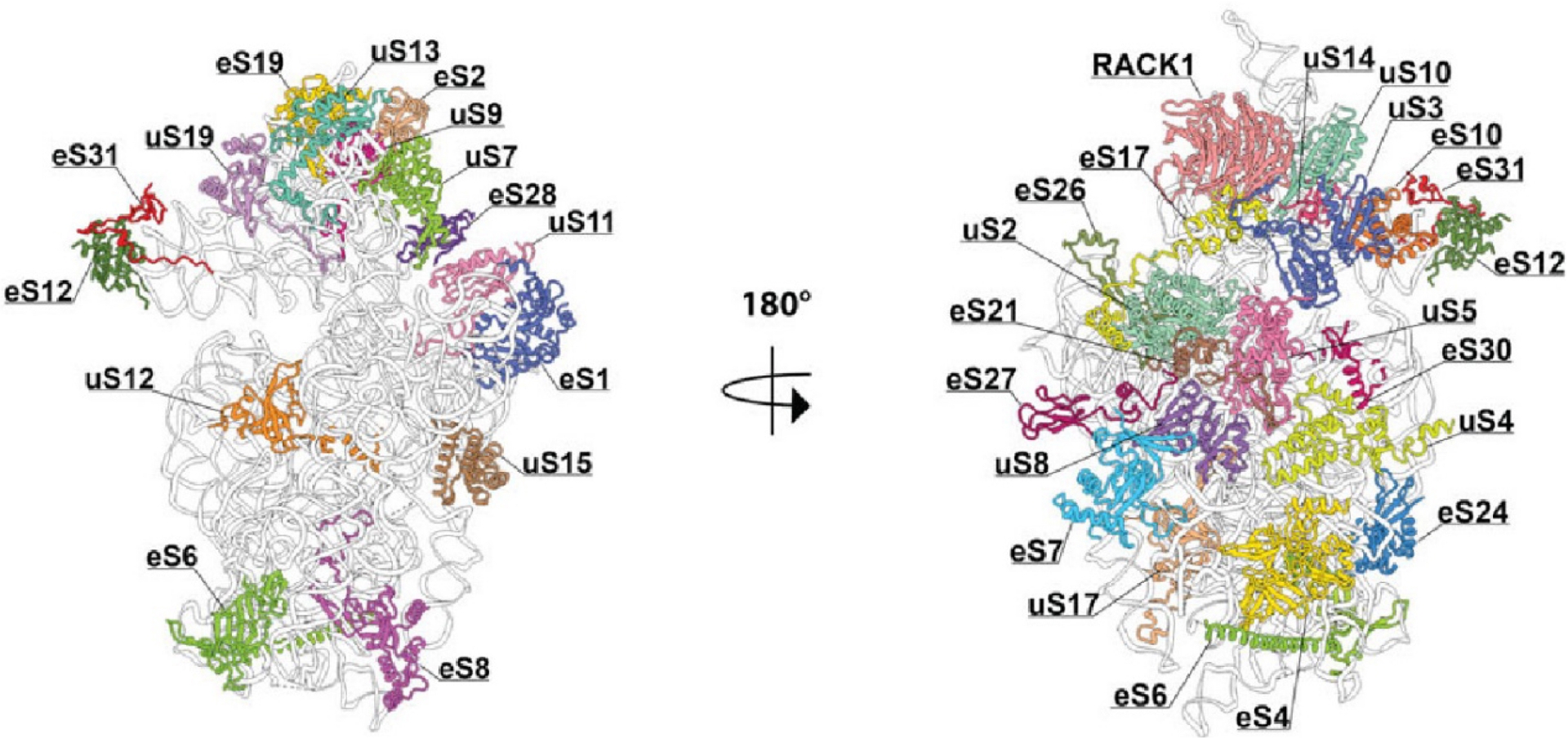

As a starting point of our research, the recently structure of isolated G. gallus 80S ribosomes (Figures 3 and 4) has been determined by a cryo-EM study (Nurullina et al., 2024).

Structure of G. gallus ribosomal 60S subunit. Ribosomal RNA is shown in grey and ribosomal proteins in color. The left side represents the ribosomal interface, while the right side represents the ribosomal solvent side.

Structure of the G. gallus ribosomal 40S subunit. Ribosomal RNA is shown in grey and ribosomal proteins in color. The left side represents the ribosomal interface, while the right side represents the ribosomal solvent side.

As results all ribosomal proteins have been modeled in the structure with the only exception of P1 and P2 proteins of the P-stalk of the large ribosomal subunit (Figure 3). This protein complex is flexible and not visible in cryo-EM structures and crystal structures of S. cerevisiae ribosomes as well (Ben-Shem et al., 2011; Milicevic et al., 2024).

The interface between ribosomal subunits, as well as the area surrounding the mRNA entrance and the polypeptide exit tunnel, is highly conserved and contains very few expansion segments and eukaryote-specific proteins. The ribosomal RNA expansion elements are located predominantly on the periphery of the solvent-exposed sides of both subunits of the eukaryotic ribosome.

The insertions of expansion segments in the sequence of the rRNA of G. gallus is conserved among other eukaryotic organisms. However, the length of these inserted ES differs between species, and some features of the expansion segments are specific to avians (Figure 5). Our map revealed differences in the structural arrangement of expansion segments in the 28S rRNA of Gallus gallus. The main differences, when compared to its human counterpart, were observed in the highly variable expansion segment ES7L and between the interaction patterns of the expansion segments ES15L, ES10L, ES9L and ES7L. These differences suggest that the packaging of expansion segments may vary from species to species. The ES7L tentacle was found to be longer than in other species, and one of our assumptions was that this tentacle could participate in the formation of tetramers and aggregates (Figure 5). The solved structure of the 80S G. gallus ribosome can be further utilized while working on the structure of the ribosomal tetramers and aggregates.

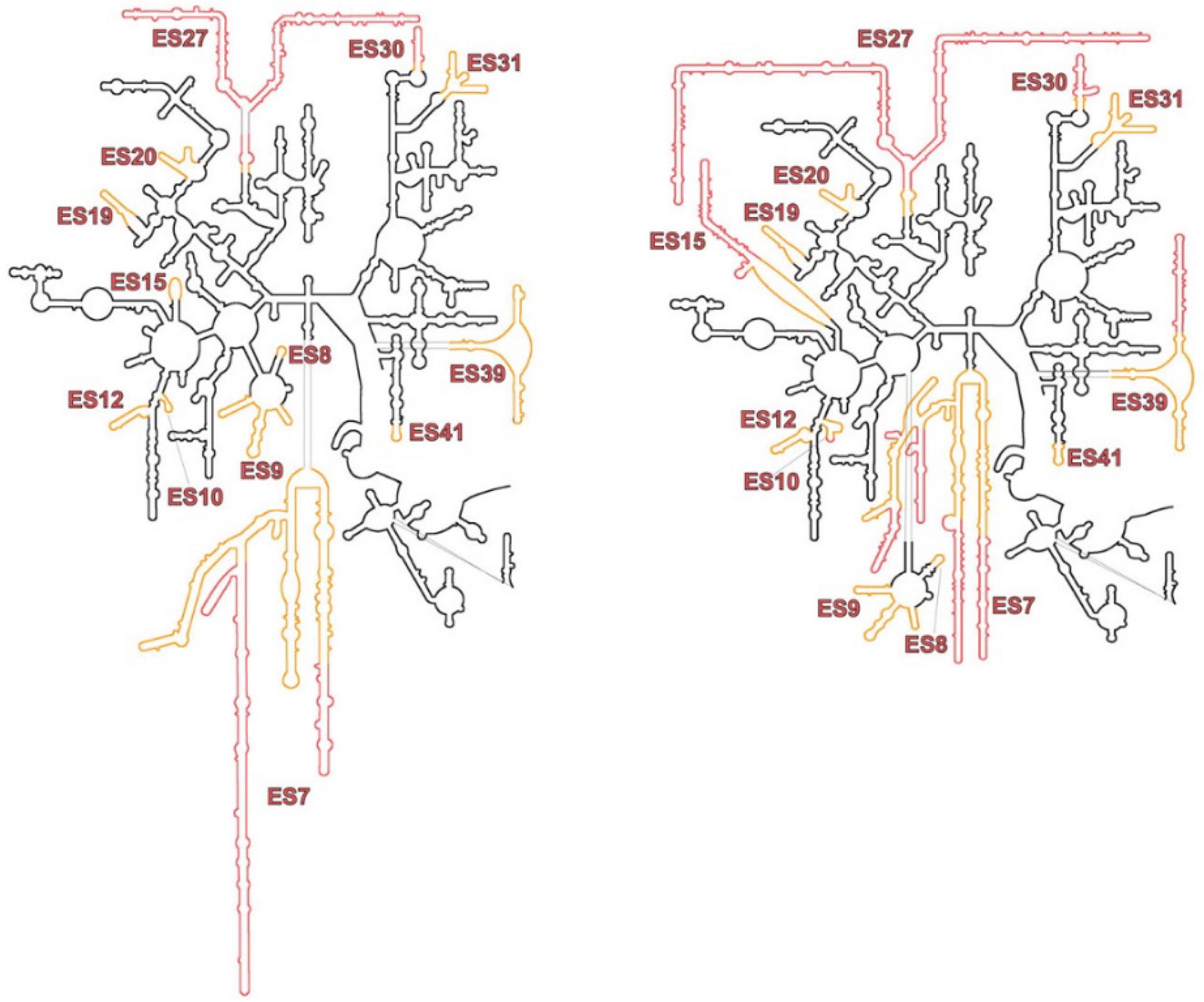

Secondary structure of 28S rRNA: on the left, the secondary structure from Gallus gallus; and on the right, the one from Homo sapiens. In black are the rRNA conserved between the two species. Expansion segments are represented in yellow/red color. Rred indicate the parts of expansion segments which are flexible and not visible in cryo-EM three-dimensional structure.

4. Conclusion

We suggest that the stabilization of chick embryo ribosomes is possible in an environment similar to stress cold conditions in vivo. It is impossible to imagine the crystallization of ribosomes containing unfolded expansion segments into 3-dimensional crystals, as was shown earlier (Milligan and Unwin, 1982). We conclude that the behavior of human ribosome during sedimentation experiments is the result of partial unfolding of ribosomal RNA during purification and sample preparation. Similar results of unfolded expansion segments were obtained in all cryo-EM studies of ribosomes from highly developed organisms including human and chick embryos (Nurullina et al., 2024; Armache et al., 2010a; Armache et al., 2010b). Therefore, it is becoming clear that some sort of stabilization is needed to decipher the ES spatial disposition. Finding the right model to address these structural questions about the role of ES is of paramount importance to dive deeper in the understanding of translation regulation at the molecular level. For this reason, we suggest using in situ cryo-ET to study ribosomal tetramers and aggregates that are stabilized under cold stress conditions. This could help resolve their three-dimensional structure, elucidate the mechanism of aggregate formation, and visualize expansion segments during ribosomal function or intermolecular contact formation.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0