1. Introduction

Karl von Frisch (1886–1982), who dedicated his life to the study of honey bees, became renowned for his discovery of the bee dance—a ritualized behavior that allows a successful forager to inform nestmates about the distance and direction of a profitable food source (e.g. von Frisch, 1965). Beyond his groundbreaking work on dance communication, von Frisch left behind a remarkably rich body of evidence on honey bee behavior, encompassing studies on navigation, vision, olfaction, taste, magnetic sensing, and more (ibid.). He often described honey bees as a “magic well” for biological discoveries—the more one draws from it, the more there is to draw.

Surprisingly, however, this fascination did not extend to the cognitive abilities of bees. Reflecting on communication behavior, von Frisch wrote: “The brain of a bee is the size of a grass seed and is not made for thinking. The actions of bees are mainly governed by instinct” (von Frisch, 1962). It is striking that such a dismissive view of bee cognition came from the very scientist most captivated by their behavioral complexity.

In recent decades, however, honey bees have emerged as a valuable model for the study of learning and memory (Giurfa, 2007; Giurfa and Sandoz, 2012; Avarguès-Weber, Deisig, et al., 2011; Menzel, 1999). More recently, they have also gained prominence in research on higher-order cognitive capacities—abilities that were long considered the exclusive domain of certain vertebrates known for their advanced learning skills (Giurfa, 2013; Giurfa, 2015).

In this review, I will examine the key contributions of honey bee research to the fields of learning and memory, and how this work has shaped our understanding of cognition. I will highlight both established findings and open questions that illustrate the extent to which honey bees have advanced our knowledge of cognitive processing—at both the behavioral and cellular levels. In doing so, I aim to emphasize the power and potential of the honey bee as a model in cognitive neuroscience.

2. Experimental access to learning and memory in honey bees

Honey bees can be individually trained to solve a wide variety of discrimination tasks. Several experimental paradigms have been developed to study learning and memory in single honey bees. This individualized approach is critical because learning and memory are the products of individual experience. It also enables a neurobiological analysis that can be directly correlated with individual performance scores.

I will describe two primary protocols widely used to investigate learning and memory in honey bees, selected for their experimental robustness and impact: (1) Conditioning of approach flights to visual targets in free-flying bees (in part 3); and (2) Olfactory conditioning of the proboscis extension reflex (PER) in harnessed bees (in part 4).

Both rely on the appetitive context of food search, using sucrose solution as a reward mimicking nectar. In these paradigms—and in various modified versions tailored to specific experimental goals—the basic design includes an acquisition (or training) phase, during which bees are exposed to a stimulus or perform a task that is reinforced, followed by a test (or retrieval) phase, in which the same stimulus is presented without reinforcement to assess memory retention. To explore generalization and discrimination capabilities, novel stimuli may also be introduced during the test phase alongside the trained stimulus. Additionally, testing in the absence of the original stimulus allows for assessment of stimulus transfer and cognitive flexibility (see below).

3. Conditioning of approach flights to visual targets in free-flying bees

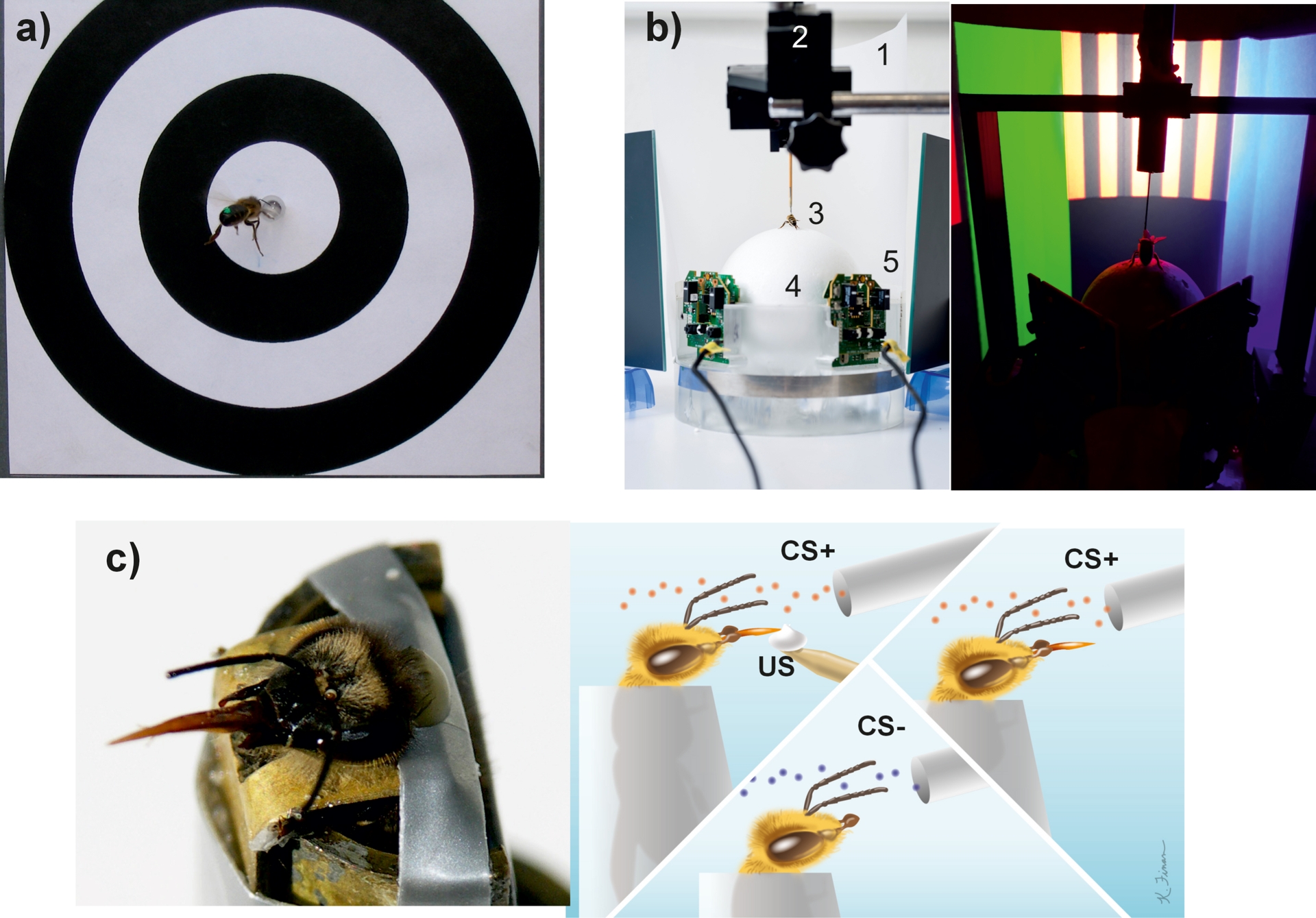

Free-flying honey bees can be conditioned to respond to various visual cues, including color, shape, pattern, motion, and depth (von Frisch, 1914; Giurfa and Menzel, 1997; Avarguès-Weber, Mota, et al., 2012). In this protocol, each bee is individually marked (typically with a colored spot on the thorax or abdomen) and displaced by the experimenter to the training site, where it receives a sucrose reward to encourage repeated visits (Figure 1a). This pre-training phase occurs in the absence of training stimuli to prevent uncontrolled associative learning. Once the bee begins visiting the training site autonomously, visual stimuli are introduced, and correct choices are reinforced with sucrose. The resulting associations may be operant, classical, or a combination of both: visual stimuli (CS) may become linked to the reward (US), to the motor response (e.g., landing), or both. Nevertheless, the task is predominantly operant, as reinforcement depends on the bee’s behavior.

Experimental protocols for the study of learning and memory in honey bees. (a) Visual appetitive conditioning of free-flying bees. A bee marked with a green spot on the abdomen is trained to collect sugar solution in the middle of a ring pattern. (b) Visual appetitive conditioning in a virtual reality (VR) environment. Left: Global view of the VR system. 1: Semicircular projection screen made of tracing paper. 2: Holding frame to place the tethered bee on the treadmill. 3: Tethered bee. 4: The treadmill is a Styrofoam ball positioned within a cylindrical support (not visible) floating on an air cushion. 5: Infrared mouse optic sensors allow to record the displacement of the ball and to reconstruct the bee’s trajectory. The video projector displaying images (not visible) is placed behind the screen. Right. Color discrimination learning in the VR setup. The bee had to learn to discriminate two vertical stimuli based on their different color and their association with reward and punishment. Stimuli were green and blue on a black-and-white grating background. (c) Olfactory appetitive conditioning of harnessed bees. Left: A bee immobilized in a tube displays the proboscis extension response (PER). Right: Schematic of a conditioning protocol in which a rewarded odorant (CS+) is paired with a sucrose solution (unconditioned stimulus, US) delivered via a toothpick, while a non-rewarded odorant (CS−) is also presented. In a retention test, the CS+ is presented without reward, and a PER to it indicates learning (conditioned response). Adapted from Giurfa (2007).

A recent variant of this protocol involves virtual reality setups, where bees walk or fly in a stationary position while being exposed to a dynamically projected visual environment that responds to their movements (a closed-loop setup) (Geng et al., 2022; Lafon et al., 2022; Buatois, Laroche, et al., 2020; Buatois, Pichot, et al., 2017; Schultheiss et al., 2017). In this setting (Figure 1b), bees efficiently learn to discriminate between virtual objects differing in color and shape (Geng et al., 2022; Rusch et al., 2017), offering new opportunities to study visual learning under highly controlled experimental conditions.

4. Olfactory conditioning of the proboscis extension reflex (PER) in harnessed bees

Harnessed honey bees can be conditioned to respond to odorants in the laboratory setting (Bitterman et al., 1983). Each bee is restrained in an individual holder that immobilizes its body while leaving the antennae and mouthparts (mandibles and proboscis) free to move (Figure 1c). When a hungry bee’s antennae are touched with sucrose solution, it reflexively extends its proboscis to drink—a behavior known as the proboscis extension response (PER). In naïve bees, odorants alone do not elicit this response. However, if an odor is presented just before sucrose (a forward pairing), an association is formed such that the odor alone can later elicit PER (Figure 1c). In classical-conditioning terms (Pavlov, 1927), the odor functions as the conditioned stimulus (CS), and sucrose as the unconditioned stimulus (US). The PER to the odor then becomes the conditioned response (CR).

Of the two protocols, it is olfactory conditioning of the proboscis extension reflex (PER) that has provided access to the neural and molecular bases of learning and memory, thanks to the possibility of recording from the bee brain in an immobilized individual that can still learn and memorize odors.

5. Cellular bases of appetitive olfactory PER conditioning

A major advance enabled by olfactory PER conditioning has been the opportunity to trace the conditioned stimulus (CS) and unconditioned stimulus (US) pathways in the honey bee brain and to study the underlying neural circuits of elemental associative learning.

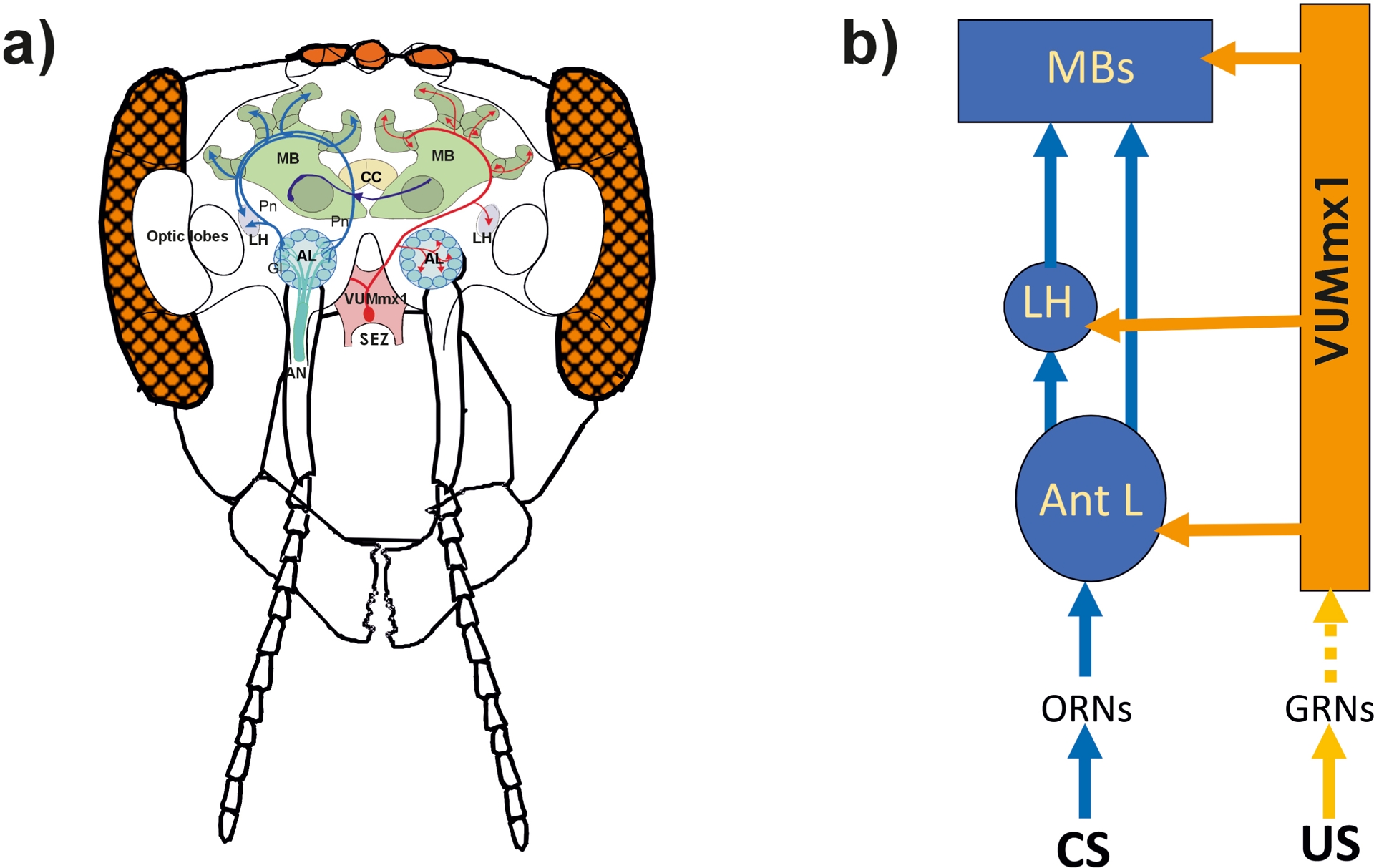

Odorants are processed via a well-defined CS processing pathway comprising multiple stages (Figure 2a). Olfactory perception begins at the antennae, where olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) are located within sensilla. These neurons transmit information to the antennal lobes, the primary olfactory centers of the insect brain. Each antennal lobe contains approximately 165 glomeruli—synaptic integration units where ORNs, inhibitory local interneurons, and projection neurons (PNs) interact. PNs relay processed olfactory information to higher-order brain centers including the lateral horn and the mushroom bodies. The mushroom bodies serve as multimodal integration centers, receiving input from olfactory, visual, gustatory, and mechanosensory modalities.

CS-US associations in the honey bee brain. (a) Scheme of a frontal view of the bee brain showing the olfactory (CS; in blue on the left) and sucrose (US, in red on the right) central pathways. The CS pathway: Olfactory sensory neurons send information to the brain via the antennal nerve (AN). In the antennal lobe (AL), these neurons synapse at the level of glomeruli (Gl) onto local interneurons (not shown) and projection neurons (Pn) conveying the olfactory information to higher-order centers, the lateral horn (LH) and the mushroom bodies (MB). MBs are interconnected through commissural tracts (in violet). The US pathway: this circuit is partially represented by the VUMmx1 neuron, which has its soma in the subesophagic zone (SEZ) and converges with the CS pathway at three main sites: the AL, the LH and the MB. CC: central complex. Adapted from Menzel and Giurfa (2001). (b) Scheme of the localization and distribution of CS-US associations in the bee brain. ORNs: olfactory receptor neurons; GRNs: gustatory receptor neurons. The dashed line between GRNs and VUMmx1 indicates that this part of the circuit is actually unknown.

Neural activity along this pathway has been studied using electrophysiology and calcium imaging (Joerges et al., 1997; Szyszka, Ditzen, et al., 2005; Denker et al., 2010; Abel et al., 2001; Mauelshagen, 1993; Yamagata et al., 2009). In experiments where proboscis movement is restricted, myogram recordings of muscle M17 (which controls proboscis extension) have been used as a proxy for the conditioned response (Rehder, 1987).

Early studies combining PER conditioning with neural interference techniques used cooling-induced retrograde amnesia to explore the role of specific brain structures in memory formation. Cooling the antennal lobes within one minute after a single conditioning trial induced memory loss, while cooling the mushroom bodies produced amnesia when done 5–7 minutes post-conditioning (Menzel, Erber, et al., 1974; Erber et al., 1980). In contrast, chilling the lateral horn had no effect. These results led to the conclusion that the mushroom bodies are essential for late short-term memory consolidation, while the antennal lobes are involved in early short-term memory (Menzel and Muller, 1996). These findings were foundational and influenced subsequent research confirming the role of mushroom bodies in memory in other insects, such as Drosophila melanogaster (Davis, 2005; Heisenberg, 2003).

Calcium imaging studies have shown that in naïve bees, odors evoke reproducible glomerular activation patterns in the antennal lobes (Joerges et al., 1997; C. G. Galizia and Menzel, 2000; Paoli and G. C. Galizia, 2021) (Figure 2a). These patterns are bilaterally symmetric and conserved across individuals (C. G. Galizia, Nagler, et al., 1998; C. G. Galizia, Sachse, et al., 1999). Each odor is thus coded by a characteristic spatial pattern, and when odors are mixed, their neural representation can reflect additive responses or dominance by a single component, depending on mixture complexity (Deisig, Giurfa, et al., 2006). As more components are added, inhibitory interactions become apparent (Joerges et al., 1997; Deisig, Giurfa, et al., 2006). While this across-fiber pattern coding persists in higher brain areas (Sandoz, 2011), the mushroom bodies exhibit sparser coding, particularly in the calyces, their input regions (Szyszka, Ditzen, et al., 2005).

Learning modifies these neural representations. Calcium imaging shortly after differential conditioning (A+ vs. B−) revealed increased glomerular activation for the rewarded odor (A), but not for the non-rewarded one (B), as well as decorrelation of odor representations, improving discrimination (Faber et al., 1999). This result was confirmed in a later study examining neural activity 2–5 hours post-training (Rath et al., 2011), where successful learners showed increased pattern separation between A and B, while non-learners did not.

At the level of the mushroom bodies (Figure 2a), recordings from Kenyon cells (KCs) showed that their responses are sparse and temporally sharp, shaped by pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms and likely by inhibitory feedback (Szyszka, Ditzen, et al., 2005). Associative learning alters these responses: while repeated odor presentation alone reduces KC activity (non-associative adaptation), pairing an odor with sucrose prolongs the KC response (Szyszka, Galkin, et al., 2008). After conditioning, responses to the CS+ recovered, while CS− responses decreased further, and the spatiotemporal patterns of KC activation changed more for CS− than for CS+.

Molecular interference studies have further clarified mechanisms underlying olfactory learning. For example, RNAi-mediated silencing of the NR1 subunit of the NMDA receptor in mushroom bodies impaired mid-term and early long-term memory, but not late long-term memory, indicating a time-dependent role of NMDA signaling (Müssig et al., 2010) (for further analyses coupling PER conditioning and molecular interferences see Schwarzel and Muller, 2006).

Despite these advances, the impact of learning on olfactory processing across the brain remains an open question. Future studies should address how different conditioning protocols and memory phases affect neural coding at multiple levels of the olfactory circuit.

Knowledge of the US processing pathway remains more fragmentary. Currently, only one neuron—the VUMmx1 neuron—is known to mediate sucrose reinforcement (Figure 2a). Located in the subesophageal zone (SEZ), the first relay of the gustatory system (Altman and Kien, 1987), VUMmx1 responds with sustained spike activity to sucrose stimulation of the antennae or proboscis (Hammer, 1993). Its axonal projections arborize bilaterally in three key brain regions: the antennal lobes, the mushroom body calyces, and the lateral horns, providing a clear anatomical basis for convergence with the olfactory CS pathway (Figures 2a,b).

VUMmx1’s role as a neural representation of the US was elegantly demonstrated by substituting sucrose with artificial depolarization of this neuron: when stimulation of VUMmx1 followed odor presentation (forward pairing), bees learned the association; backward pairing did not induce learning (Hammer, 1993). This mirrored results with actual sucrose reinforcement and confirmed that VUMmx1 encodes the instructive value of the US.

VUMmx1 belongs to a class of octopamine-immunoreactive neurons (Kreissl et al., 1994). Octopamine is a biogenic amine known to promote arousal and behavioral activation in invertebrates (Libersat and Pflüger, 2004; R. Huber, 2005). In bees, it enhances responsiveness to both sucrose (Scheiner et al., 2002) and odors (Mercer and Menzel, 1982). When octopamine was injected into the antennal lobes or mushroom bodies (but not the lateral horn) paired with an odor, it substituted for the sucrose reward and induced a lasting PER to the odor (Hammer and Menzel, 1998), demonstrating that octopamine acts as an instructive signal, , i.e. as a system allowing ordering, prioritizing and assigning a “good” label to odorants (Giurfa, 2006).

Altogether, these findings demonstrate that elemental associative olfactory learning can be dissected at both behavioral and cellular levels in honey bees. The bee brain enables the mapping of distributed but localized interactions between CS and US pathways (Figure 2b). These interactions occur in at least three regions—antennal lobes, mushroom bodies, and lateral horns—illustrating a combination of distribution (multiple sites) and localization (precise synaptic convergence). While these sites may appear redundant, their contributions may differ, suggesting that distinct types of learning and memory may be mediated by specific brain regions—a hypothesis to be explored in the following sections.

6. Non-elemental learning in bees

Elemental appetitive learning, as discussed above, relies on the establishment of direct associative links between two specific and unambiguous events in the bee’s environment (e.g. CS → US). In contrast, the forms of associative learning discussed here involve events that are ambiguous in terms of their outcomes, rendering simple one-to-one associative links ineffective. They thus represent greater cognitive challenges and provide a means to assess the capacity of the bee’s miniature brain to solve higher-order cognitive tasks.

A typical example is “negative patterning”, in which bees must learn to discriminate a non-reinforced compound from its individually reinforced components (A+, B+ vs. AB−). This problem resists elemental solutions because bees must recognize that the compound AB differs fundamentally from the linear sum of A and B. Animals learning that both A and B are individually reinforced should inhibit the summed expectation that the compound AB is twice as rewarding. Accordingly, the task is described as non-linear. A related case is biconditional discrimination, where bees are required to respond to the compounds AB and CD, but not to AC and BD (AB+, CD+, AC−, BD−). In this scenario, each individual element (A, B, C, D) is equally paired with reinforcement and non-reinforcement, precluding a solution based on individual associative strength. These examples illustrate that solving such tasks requires more complex computational strategies.

One influential approach to these problems is configural learning theory, which posits that compound stimuli are processed as unique configurations distinct from their elements (e.g., AB = X ≠ A + B) (Pearce, 1994). According to this view, animals trained with AB respond minimally to A or B alone. Another account is the unique-cue theory, which proposes that the compound AB is processed as the sum of its components plus an additional, configural cue (u) specific to the combination (AB = A + B + u) (Whitlow and Wagner, 1972). This theory allows for stronger responses to individual components and suggests that the compound carries a unique signature.

Due to their complexity, such tasks have rarely been studied in invertebrates. Nonetheless, a number of studies have explored elemental vs. non-elemental learning in honey bees using both visual conditioning of free-flying bees and olfactory PER conditioning. In both modalities, bees successfully learned biconditional discriminations (AB+, CD+, AC−, BD−). In the visual domain, bees discriminated complex patterns conforming to this structure (Schubert et al., 2002), while in olfaction, bees trained with odorant mixtures (Chandra and Smith, 1998) learned to respond to compounds independently of the ambiguity of their components. These results demonstrate that under specific conditions, both visual and olfactory compounds are learned as configurations, distinct from the simple sum of their elements.

This conclusion is further supported by studies showing that bees can solve negative patterning discriminations (A+, B+, AB−) in both the visual (Schubert et al., 2002) and olfactory domains (Deisig, Lachnit, Giurfa, et al., 2001; Deisig, Lachnit, Giurfa, et al., 2002; Deisig, Lachnit, Sandoz, et al., 2003; Deisig, Sandoz, et al., 2007). Solving this task requires that bees treat the compound AB as distinct from A and B. Experiments designed to distinguish between configural and unique-cue theories showed that bees’ performance was consistent with the latter: bees perceive the components of a compound but also assign a unique identity to the mixture based on the interaction of these components (Deisig, Lachnit, Sandoz, et al., 2003).

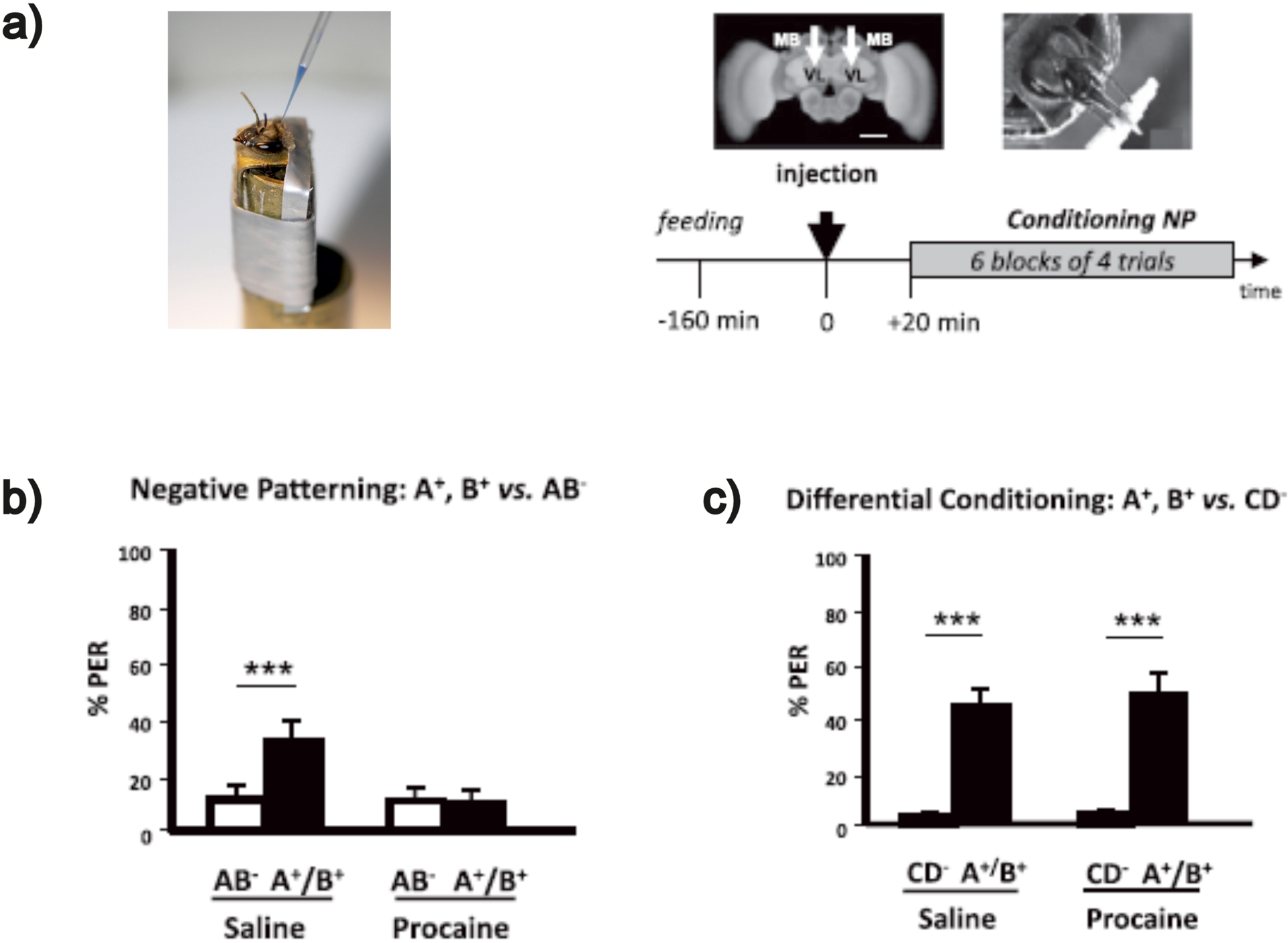

7. Cellular bases of non-elemental learning

The investigation of the neural substrates of non-elemental learning took advantage of the olfactory conditioning of PER. The use of a negative patterning protocol allowed asking the question of the neural substrates underlying this form of non-linear problem solving in the olfactory domain (Devaud, Papouin, et al., 2015). Control bees that received saline solution injections at the level of the mushroom bodies (Figure 3a) were able to solve a negative patterning discrimination (A+, B+, AB−). Yet, when mushroom body activity was blocked locally using injections of procaine (Devaud, Blunk, et al., 2007)—a sodium and potassium channel blocker—, bees were unable to learn the negative patterning task (Figure 3b). A critical control experiment involved again mushroom body blockade using procaine, but this time, bees were subjected to an elemental discrimination, which nevertheless resembled a negative patterning problem: A+, B+, CD− (Figure 3c); in this case, each odorant is associated univocally with the presence or absence of reinforcement so that there is no ambiguity in the problem. Controls and bees with mushroom bodies blocked by procaine could solve equally well this discrimination (Figure 3c), thus showing that the incapacity to solve the negative patterning discrimination in the absence of mushroom bodies was inherent to the nature of the problem trained. These results thus show a specific role for the mushroom bodies in non-elemental learning (Devaud, Papouin, et al., 2015).

Mushroom body blockade impairs negative patterning (NP) discrimination. (a) Left: harnessed honey bee injected in the mushroom bodies (MBs). Right: Experimental protocol. After feeding and rest, bees were injected bilaterally with either the anesthetic procaine or saline solution for control bees (black arrow at time 0). The white arrows indicate the sites (VL) of bilateral injections (scale bar: 250 μm). Twenty min after injection, bees were conditioned following a NP regime. (b) Percentage of conditioned PER of a group of bees injected with saline solution (controls) in response to rewarded pure odorants (A+/B+, black bar) and to an unrewarded compound (AB−, white bar) at the end of conditioning (las conditioning block). Saline-injected bees learned to respond significantly more to the odorants A+ and B+ than to its unrewarded compound (AB−). Procaine-injected bees did not learn the NP discrimination. (c) When bees were conditioned with an elemental, non-ambiguous discrimination (CD− vs. A+/B+), both saline-injected and procaine-injected bees learned the discrimination, thus showing that MBs are required for non-elemental learning but are dispensable for elemental learning. Adapted from Devaud, Papouin, et al. (2015).

Furthermore, local injections of picrotoxin, a GABAergic inhibitor, into mushroom bodies were used to dissect the contributions of two feedback tracks of GABAergic neurons, the A3v neurons—which provide GABAergic input from the lobes to the calyces of the mushroom bodies (i.e. output → input)—and the A3d neurons—which provide GABAergic input from the lobes to the lobes of the mushroom bodies (i.e. output → output) (Rybak and Menzel, 1993). Injections of picrotoxin into the calyces—but not into the lobes—disrupted negative patterning performance by preventing suppression of responses to the non-reinforced compound AB (Devaud, Papouin, et al., 2015). This finding highlights the importance of GABAergic feedback inhibition from Av3 neurons at the mushroom body input for solving such non-linear tasks.

8. Positive transfer of learning

In this section, I focus on problem solving in which animals respond adaptively to novel stimuli they have never encountered before—stimuli that do not predict a specific outcome based solely on the animals’ past experience. Such positive transfer of learning (Robertson, 2001) differs fundamentally from elemental forms of learning, which link known stimuli or actions to specific reinforcers. In the cases considered here, responses may become independent of the physical nature of the presented stimuli and are instead guided by abstract rules (e.g., relational rules such as “on top of” or “larger than”), which can be applied regardless of stimulus similarity. Most of these experiments have been conducted in the visual modality, i.e. with free-flying bees trained to solve visual discriminations (Avarguès-Weber, Deisig, et al., 2011; Avarguès-Weber and Giurfa, 2014).

8.1. Categorization of visual stimuli

Positive transfer of learning is a hallmark of categorization performance. Categorization refers to the classification of perceptual inputs into functional groups (Zentall, Galizio, et al., 2002). It is the ability to group distinguishable objects or events based on a common feature or set of features, and to respond similarly to them (Zentall, Galizio, et al., 2002; Troje et al., 1999; L. Huber et al., 2000). Categorization thus involves extracting defining features from the environment. A typical categorization experiment trains an animal to extract a category’s basic attributes and tests its performance using novel stimuli that either do or do not share these attributes. If the animal chooses the novel stimuli based on these defining features, it demonstrates category learning and positive transfer.

Several studies have demonstrated visual categorization in free-flying honey bees trained to discriminate patterns and shapes. For example, van Hateren et al. (1990) trained bees to distinguish between vertical gratings with different orientations (e.g., 45° vs. 135°), rewarding only one orientation with sucrose solution. Each bee was trained with a changing succession of pairs of different gratings, one of which was always rewarded and the other not. Although the specific gratings changed across trials, the rewarded and non-rewarded gratings maintained consistent orientations. Bees learned to extract and respond to the common orientation among rewarded stimuli and transferred this knowledge to novel, non-rewarded patterns that shared the trained orientation.

Bees can also categorize visual patterns based on bilateral symmetry. When trained to discriminate symmetrical from asymmetrical patterns, they generalize this knowledge to novel patterns (Giurfa, Eichmann, et al., 1996). Similar capacities apply to radial symmetry, concentric organization, pattern disruption (see Benard et al., 2006, for review), and even photographs belonging to a given class, such as flowers or landscapes (S. Zhang et al., 2004).

To explain how bees categorize highly variable photographs of, for example, radial flowers, Stach et al. (2004) proposed that bees integrate multiple coexisting orientations into a global, multi-feature representation. A category such as “radial flower” might be defined by five or more radiating edges. Bees trained with complex patterns sharing such a layout transferred their responses to novel patterns that preserved the trained orientation configuration. They even responded to patterns with fewer correct orientations based on how closely these matched the trained template (ibid.). Thus, honey bees extract regularities and generate generalized object representations from finite feature sets.

These findings show that honey bees exhibit positive transfer from trained to novel stimuli in a manner consistent with categorization. However, such results may admit an elemental interpretation. If categorization is based on specific features such as orientation, its neural implementation may be straightforward. Stimuli sharing a feature may activate the same orientation detectors in the bee optic lobes. The orientation and tuning of these detectors have been already characterized by means of electrophysiological recordings in the honey bee optic lobes (Yang and Maddess, 1997). Category learning could thus involve reinforcing associations between symmetry detectors and reward pathways, akin to Pavlovian conditioning. From this view, although categorization involves positive transfer, it could be based on elemental stimulus-reinforcer links.

8.2. Rule learning

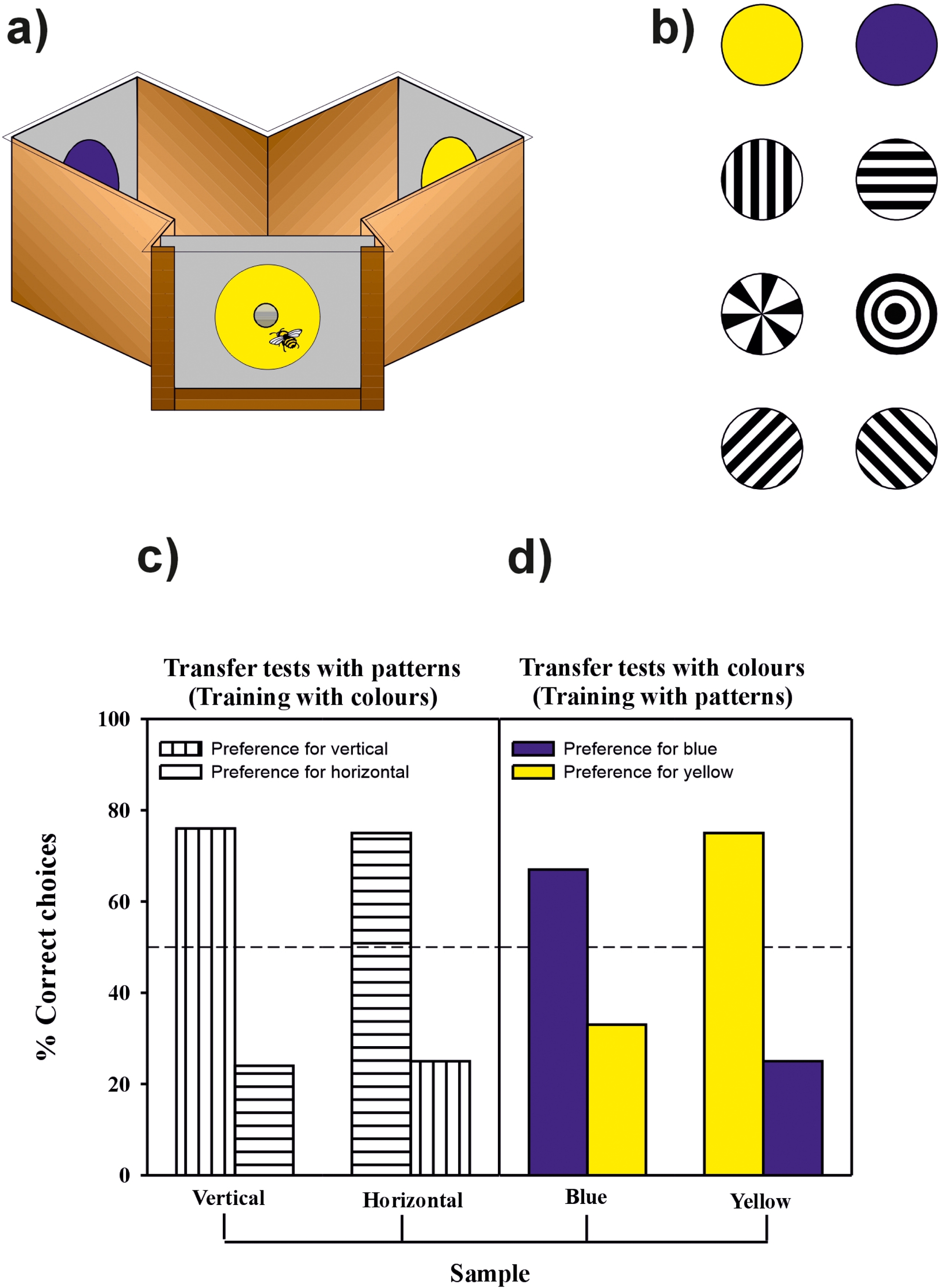

In contrast, rule learning involves learning relationships between objects, not the objects themselves. Therefore, positive transfer occurs independently of the stimuli’s physical nature (Zentall, Galizio, et al., 2002; Zentall, Wasserman, et al., 2008). Classic examples include the rules of sameness and difference, assessed through delayed matching-to-sample (DMTS) and delayed non-matching-to-sample (DNMTS) tasks, respectively.

In DMTS, animals are shown a sample, followed by a choice between stimuli where one matches the sample. Reinforcement follows selection of the matching stimulus. Since samples vary, animals must learn the abstract rule: “always choose what you were shown.” In DNMTS, the rule is reversed: “always choose the different stimulus.”

Honey bees trained in a Y-maze learned both rules (Giurfa, S. W. Zhang, et al., 2001). Bees were trained in a DMTS problem in which they were presented with a changing non-rewarded sample (i.e. one of two different color disks or one of two different black-and-white gratings, vertical or horizontal) at the entrance of a maze (Figure 4). The bees were rewarded only if they chose the stimulus identical to the sample once within the maze. Bees trained with colors and presented in transfer tests with black-and-white gratings that they did not experience before solved the problem and chose the grating identical to the sample at the entrance of the maze. Similarly, bees trained with the gratings and tested with colors in transfer tests also solved the problem and chose the novel color corresponding to that of the sample grating at the maze entrance. Transfer was not limited to different kinds of modalities (pattern vs. color) within the visual domain, but could also operate between drastically different domains such as olfaction and vision, demonstrating cross-modal transfer. This transfer even spanned vision and olfaction. Bees also learned a rule of difference in DNMTS tasks (ibid.). Working memory underlying DMTS tasks in bees lasts about 5 seconds (S. W. Zhang et al., 2005), consistent with short-term memory durations observed in simpler associative tasks (Menzel, 1999).

Rule learning in honey bees. Honey bees trained to collect sugar solution in a Y-maze (a) on a series of different patterns or two different colors (b) learn a rule of sameness. Learning and transfer performance of bees in a delayed matching-to-sample task in which they were trained to colors (Experiment 1) or to black-and-white, vertical and horizontal gratings (Experiment 2). (c,d) Transfer tests with novel stimuli. (c) In Experiment 1, bees trained on the colors were tested on the gratings. (d) In Experiment 2, bees trained on the gratings were tested on the colors. In both cases bees chose the novel stimuli corresponding to the sample although they had no experience with such test stimuli. n denotes number of choices evaluated. Adapted from Giurfa, S. W. Zhang, et al. (2001).

8.3. Spatial and simultaneous concept learning

Bees can also learn spatial concepts, such as “above”, “below”, “left of”, and “right of”, which are essential for orientation and displacement. The capacity to learn an above/below relationship between visual stimuli and to transfer it to novel stimuli that are perceptually different from those used during the training was shown by training free-flying bees to choose visual stimuli presented above or below a horizontal bar (Avarguès-Weber, Dyer and Giurfa, 2011). Training followed a differential conditioning procedure in which one spatial relation (e.g. “target above bar”) was associated with sucrose solution whilst the other relation (e.g. “target below bar”) was associated with quinine solution. One group of bees was rewarded on the “target above bar” relation while another group was rewarded on the “target below bar” relation. After completing the training, bees were subjected to a non-rewarded transfer test in which a novel target stimulus (not used during the training) was presented above or below the bar. Despite the novelty of the test situation, bees responded appropriately: if trained for the above relationship they chose the novel stimulus above the bar, and if trained for the below relationship they chose the novel stimulus below the bar (ibid.).

Bees can also acquire multiple concepts simultaneously. In one study, they learned both spatial (e.g., “above/below”, “left/right”) and difference concepts (Avarguès-Weber, Dyer, Combe, et al., 2012). Stimuli featured two images in specific spatial relations, and bees had to select configurations that both obeyed a spatial rule and involved different images. Bees generalized these concepts to novel images. In conflict tests, where one concept was satisfied but not the other, bees showed no preference, suggesting equal weighting of both concepts.

9. Numerical cognition

A new research field on bee numerosity has revealed a remarkable capacity for numerical cognition (see reviews in Giurfa, 2019a; Giurfa, 2019b). Spatial arrays of items have been used in experiments employing a delayed matching-to-sample protocol, in which bees were trained to fly into a Y-maze and choose the stimulus that matched the numerosity of a sample array presented at the maze entrance (Gross et al., 2009). Bees trained to match sample arrays containing two or three items successfully learned the task and transferred their choice to novel arrays that maintained the same number of items but differed in color, shape, and configuration. However, performance declined when the sample contained four items, and higher numerosities resulted in increasingly unsuccessful outcomes. These results suggest that the upper limit of numerical discrimination in these conditions may be close to four (ibid.).

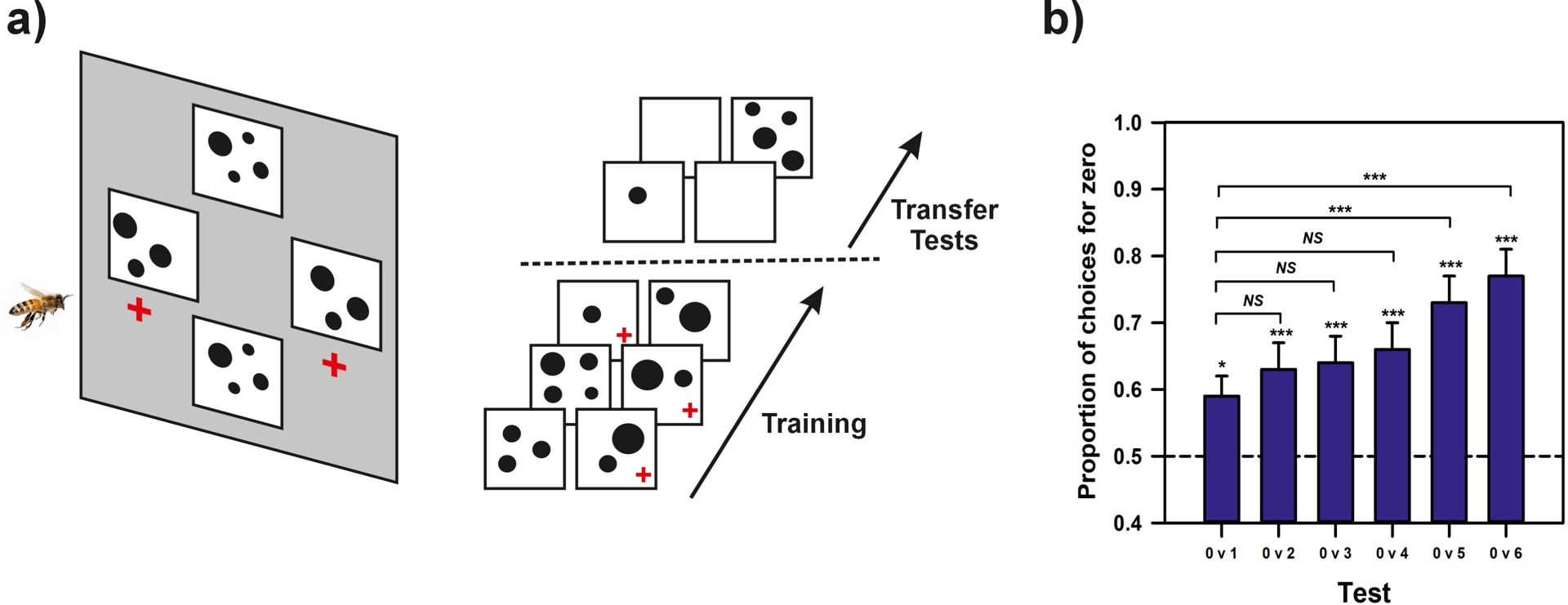

Like some primates and birds, bees also appear to possess a concept of zero, understood as the lower bound of a continuous numerical scale (Nieder, 2016). This was demonstrated in experiments where bees were trained to follow the constant rule of selecting the smaller of two numerosities (Figure 5a), varying between 1 and 4. When tested with an unfamiliar comparison—one item versus an empty set—they reliably chose the empty set, indicating that they treated it as a quantity smaller than one, two, or more items (Howard et al., 2018) (Figure 5b). Furthermore, their performance improved with increasing numerical distance (e.g., 0 vs. 6 was easier than 0 vs. 1; Figure 5b), replicating the numerical distance effect observed in vertebrates, where discrimination between numbers improves as the numerical difference between them increases.

Zero representation in bee numerosity. (a) Left. Experimental setup for studying the presence of zero in bee numerosity. Bees were trained to fly to a vertical screen displaying two numerosities via four stimuli made of black dots (here 3 vs. 4). Stimuli were controlled to discard the use of low-level cues. One numerosity (3) was rewarded with sucrose solution (red + sign). Right. Training and tests. Bees were trained with varying pairs of numerosities; they were rewarded for choosing always the smaller numerosity (indicated by a red + sign). When they reached a % of correct choices > 80%, they were tested with an empty background (“zero”) vs. a single item. Further transfer tests opposing the empty background to two, three, four, five and six items were also performed. (b) Results of the transfer tests. Bees trained to choose the smaller numerosity preferred the zero stimulus to any other numerosity. Their performance is consistent with the numerical distance effect’ as the ability to discriminate between numbers improves as the numerical distance between them increases.

Because this study relied on the bees’ capacity to use relative numerosity (“choose the smaller set”), another experiment was designed to test whether bees could also use absolute numerosity (Bortot et al., 2019). One group of bees (“larger”) was trained to choose 3 over 2, while another group (“smaller”) was trained to choose 3 over 4. In subsequent tests, both groups were presented with the previously rewarded numerosity (3) and a novel one (4 for “larger”, 2 for “smaller”). Bees in both groups preferred the three-item array, suggesting a tendency to rely on absolute numerosity—unlike many vertebrates, which typically favor relative rules under similar conditions. Nonetheless, a numerical size effect, consistent with Weber’s law, was observed: discrimination performance declined as overall numerical magnitude increased (e.g., 3 vs. 4 was harder than 2 vs. 3) (ibid.).

Bees have also been shown to perform rudimentary arithmetic operations. In a recent study (Howard et al., 2019a), the color of a sample array (blue or yellow) indicated which arithmetic operation to perform (Figure 1b). If the sample was blue, bees had to choose the array that contained one more item (addition); if yellow, they had to select the array with one fewer item (subtraction). Bees learned the task and successfully transferred this rule to novel numerosities, adjusting their response based on the indicated operation. These findings demonstrate that bees can master simple arithmetic operations under controlled conditions (ibid.).

Symbolic matching has also been explored in bees. In one experiment (Howard et al., 2019b), different groups of bees were trained to match a visual sign (e.g., “N” or “⊥”) to a specific numerosity (2 or 3), or vice versa. Both groups learned their respective associations and generalized them to novel stimuli with varying colors, shapes, and configurations. However, they failed to reverse the direction of the learned association (i.e., from number-to-sign if trained on sign-to-number, and vice versa). Given that bees are capable of learning other reversal tasks, this failure may reflect a specific limitation related to the numerical aspect of the task, suggesting boundaries to their symbolic numerical competences.

Similarities with vertebrate numerosity extend to the existence of a “mental number line” (MNL), the representation of numbers by which humans organize numbers spatially from left to right according to their magnitude. A recent study explored how bees trained to specific numerosities (e.g., 3) associated with a reward of sucrose solution respond to novel numbers (i.e. 1 or 5) when identical options (1 vs. 1 or 5 vs. 5) are shown on the left and the right, in the absence of the trained numerosity (Giurfa, Marcout, et al., 2022). Results showed that bees order numbers from left to right according to their magnitude (i.e. after being trained to 3, they preferred 1 on the left and 5 on the right) and that the location of a number on that line varies with the reference number previously trained. Thus, the MNL is a form of numeric representation that is evolutionary conserved across nervous systems endowed with a sense of number, irrespective of their neural complexity.

Overall, these results indicate that bees and vertebrates share similarities in their numeric competences, thus suggesting that numerosity is evolutionary conserved and can be implemented in miniature brains.

10. An ecological context for honey bee cognition

While laboratory paradigms have revealed the extent and richness of honey bee cognition, it remains essential to understand how these capacities are expressed in natural behavior. Honey bees are central-place foragers, meaning that their foraging trips always begin and end at the hive. To succeed in this task, they rely on flexible strategies that allow them to recognize and generalize visual patterns both at flowers and at the nest. Bees extract salient image features and combine them into specific configural representations that support flower recognition (Stach et al., 2004; Avarguès-Weber, Portelli, et al., 2010). They can then generalize these representations to novel visual images that share the same configurations, even when other spatial details or positions within the visual field vary substantially. Such capacities are likely involved in extracting and recognizing relational concepts, where the critical information lies in the relationships among visual features.

During foraging bouts, bees also rely on celestial cues for compass navigation, while prominent landmarks and landscape features help define routes and support orientation (Collett, 1996; Chittka et al., 1995; Menzel and Greggers, 2015; Menzel, De Marco, et al., 2006). In this context, the ability to represent spatial relationships in a generalized form around the hive or food sources is particularly advantageous. Extracting relations such as “same”, “different”, “to the right (or left) of”, or “above (below)” may help bees maintain reliable routes in a changing environment, where landmarks themselves can vary in appearance (Avarguès-Weber and Giurfa, 2013).

In addition, numerical information contributes to efficient foraging and navigation. Estimating the number of landmarks can indicate where to land, while assessing the number of flowers within a patch provides an estimate of its richness. Such numerical competencies likely enhance foraging efficiency and, ultimately, colony survival. Selective pressures may therefore have favored the evolution of numerical abilities in bees, much as they have in vertebrates.

Finally, non-elemental learning capabilities are especially advantageous in the complex floral market. Honey bees typically exploit one floral species at a time—a behavior known as flower constancy (Grant, 1950; Free, 1963; Waser, 1986)—which maximizes foraging efficiency. Yet many floral species share odor components, and if bees were to generalize indiscriminately across species with overlapping odor cues, flower constancy would break down. By learning specific odor combinations as unique configurations, distinct from the mere sum of their components, bees can discriminate among species and thus sustain both flower constancy and foraging efficiency.

These arguments help bridge the gap between experimental paradigms and natural behavior, showing that findings from controlled laboratory setups reveal capacities with genuine adaptive value in the wild. They also reinforce the status of honey bees as a powerful model for studying cognition beyond simple associative learning.

11. Conclusion

This review highlights the remarkable richness and flexibility of experience-dependent behavior in honey bees, and the fact that various forms of cognitive processing based on associative learning—ranging from simple to more complex—can be formalized and studied under controlled laboratory conditions. The adoption of rigorous definitions from elemental and non-elemental learning frameworks provides a valuable foundation for assessing the extent to which honey bees can transcend basic associative processes. As demonstrated by the numerous examples reviewed here, such an experimental approach has revealed a level of cognitive sophistication in bees that challenges traditional views of insect intelligence as inherently limited.

While specific neural circuits have been identified for elemental forms of associative learning, the neural basis of more complex forms of problem solving remains poorly understood. Existing evidence consistently implicates the mushroom bodies—a central structure in the insect brain—in learning and memory. Although certain elemental discriminations can be accomplished without mushroom bodies (e.g., Devaud, Papouin, et al., 2015), this does not appear to be the case for higher-order, non-elemental tasks. Although the precise substrates and circuits underlying complex cognition in the bee brain remain to be identified, there is reason for optimism. What is now required is a conceptual shift that promotes deeper investigation into complex cognitive processing in insect brains.

A key question for future research concerns the specific limitations of the bee brain compared to larger brains, and what structural or functional constraints might underlie them. Addressing this question requires a better understanding of the deficits or boundaries of bee cognition—an area that remains largely unexplored. Due to space limitations, we have not addressed how various forms of learning function in ecologically relevant contexts such as navigation and communication. These domains offer additional and promising frameworks for studying cognitive processing. Questions such as how bees represent space or flexibly adjust their communication strategies remain crucial for evaluating the cognitive potential of the bee brain. Ultimately, such questions should be linked to specific neural circuits and structures—a goal that remains elusive, but attainable.

Research on honey bee behavior invites an optimistic perspective on these challenges. Because honey bee learning shares important features with that of vertebrates, this insect may serve as a powerful model for investigating intermediate levels of cognitive complexity and their neural underpinnings.

Declaration of interests

Views and opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

The author does not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and has declared no affiliations other than their research organization.

Funding

The work of MG is currently funded by the European Union (ERC Advanced Grant COGNIBRAINS; project number 835032).

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0