Research highlights

- ∙ Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) is one of the most important neurosteroids to modulate neuronal activity.

- ∙ DHEAS alters the secretory activity of the SCO and enhances the Reissner’s fiber amounts probably via a modulation of serotonergic innervations of the SCO.

1. Introduction

The concept of neurosteroids was attributed regarding the origin of synthesis or production. These molecules are recognized as modulators of neuronal activities and classified into two types: exogenous (synthetic) and endogenous steroids. The latter is subdivided into hormonal type (produced by endocrine glands) and neurosteroids (produced by the nervous tissue) [1], especially in neuronal and glial cells [2]. Previous works have shown that the neuroactive neurosteroid Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is present in the brain tissue independently of its peripheral origin [3]. The enzymes required for DHEA biosynthesis have also been found in the brain [4, 5], both in astrocytes [6, 7] and neurons [8, 9]. Furthermore, DHEA and its sulfate ester (DHEAS) might exert important functions in the nervous system such as modulation of neuronal death and survival [10, 11, 12], brain development [13], cognition [14, 15] and behavior [16, 17, 18]. The effects of DHEA and DHEAS on the nervous system are in part mediated by the modulation of several neurotransmitter systems, such as the dopaminergic [19, 20, 21], glutamatergic [11, 22] serotonergic [19, 23] and GABAergic systems [24, 25]. On the basis of literature, our knowledge on the effects of neurosteroids upon the glial cells is still very poor, even on those constituting the circumventricular organs, particularly the Subcommissural organ (SCO). The latter is known as a secretory organ located at the entrance of the cerebral aqueduct below the posterior commissure. This brain gland releases glycoproteins of high molecular weight into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) where they aggregate to form Reissner’s fiber (RF) [26]. Several roles have been proposed for this gland such as water homeostasis [27, 28], neuronal survival [29], detoxification [30], monoamines clearance in the CSF [31], lordosis [32], in the pathophysiology of hydrocephalus [33] and possibly of hepatic encephalopathy [34]. Previous works have shown that the SCO receives several neuronal innervations of GABAergic [35, 36], noradrenergic and dopaminergic [27] and serotonergic nature [28, 34, 37]. The latter is the most influential system upon the secretory activity of the SCO in different mammalian species [34, 38, 39, 40, 41]. Thereby, we aimed, throughout the present investigation, to test the possible modulator effects of the neurosteroid DHEAS on the secretory activity of the SCO in the normal rat, together with the assessment of serotonin expression in the dorsal raphe nucleus and the innervating fibers reaching the SCO in the same experimental conditions, by means of an immunohistochemical approach.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals and drug treatment

All experiments were carried out in the adult male Sprague Dewley rat housed at a constant room temperature (25 °C), with a 12 h dark-light cycle with free access to food in all studied groups. Rats were treated in compliance with the guidelines of Cadi Ayyad University, Marrakech (Morocco). All procedures were in accordance with the European decree, related to the ethical evaluation and authorization of projects using animals for experimental procedures, 1 February 2013, NOR: AGRG1238767A. Thus, all efforts were made to minimize the number of animals and suffering.

Animals were divided into 2 groups: the first one of saline controls (n = 5) with a single injection of saline physiological buffer (NaCl 0.9%. i.p), while in the other group (n = 5) rats were subjected to a single intraperitoneal injection with the neurosteroid DHEAS (5 mg/kg B.W) purchased from Sigma (Oakville, ON, Canada). The experiments were made in the morning between 10 am and 12 am.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry

30 min after injection, enough for DHEAS to cross the blood brain barrier and induce its central effects [42], rats from each group were anesthetised intraperitonially with sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg. i.p.) and perfused transcardially with chilled physiological saline and paraformaldehyde (4%) in phosphate buffer (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4). Brains were post-fixed in the same fixative oven night at 4 °C, dehydrated in graded ethanol solutions (50–100%), passed through serial polyethylene glycol solutions (PEG) and embedded in pure PEG. Frontal sections (20 μm) were cut with a microtome, collected and rinsed in PBS to wash out the fixative. Sections were performed throughout all the SCO and the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) and immunolabelling was performed on six selected sections. Free floating sections were incubated in 5-HT or polyclonal RF antibodies [29] respectively, diluted 1/1000 in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 1% bovine serum albumin. After three washes in the same buffer, sections were incubated for 2 h at room temperature in goat anti-rabbit biotinylated immunoglobulins (1/1000, Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark) and then, after washing, incubated in streptavidin peroxidase (1/2000; Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark). Peroxidase activity was revealed by incubating sections in 0.03% DAB (3-3-diaminobenzidine, Sigma, Oakville, Canada) in 0.05 M Tris buffer, pH 7.5, containing 0.01% H2O2. The sections were then collected, dehydrated and mounted in Eukit for optic microscopy observation. The specificity of the immunoreactive materials was tested following the subjection of the slides to same immunohistochemical protocol described above by either using the preimmune serum or omitting of the primary antibodies. These tests showed that both primary antibodies used against RF and 5-HT display specific labelling [34]. Quantification of the immunoreactive materials was performed according to the protocol published by Vilaplana and Lavialle 1999 [43]. Briefly, the digitization and storage of images were performed using a Zeiss-Axioskop 40 microscope equipped by a digital Canon camera. Images were digitized into 512/512 pixels with eight bits of grey resolution and were stored in TIFF format. Image processing and quantification were performed using Adobe Photoshop v.6.0. After transformation of each image to the binary mode, the percentages of black pixels were obtained using the image histogram option of Adobe Photoshops. This percentage corresponds to Reissner’s fiber immunopositive areas throughout the whole SCO including the apical and the basal parts or 5-HT immunoreactive area in the basal part surrounding the SCO or the median part of the raphe nucleus and the fibers extending outside the organ. Five sections from saline controls and DHEAS rats were randomly chosen for the quantification. The specificity of the immunoreactive materials was tested following subjection of the slides to the same immunohistochemical procedure as described above and using the pre-immune serum or omitting of the primary antibodies. These tests showed that the primary antibodies used against 5-HT and RF display specific labelling as has been previously published [28, 34].

2.3. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and were subjected to Student T test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance between controls and DHEAS group. Statistical analysis was performed using the computer software SPSS 10.0 for Windows® (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

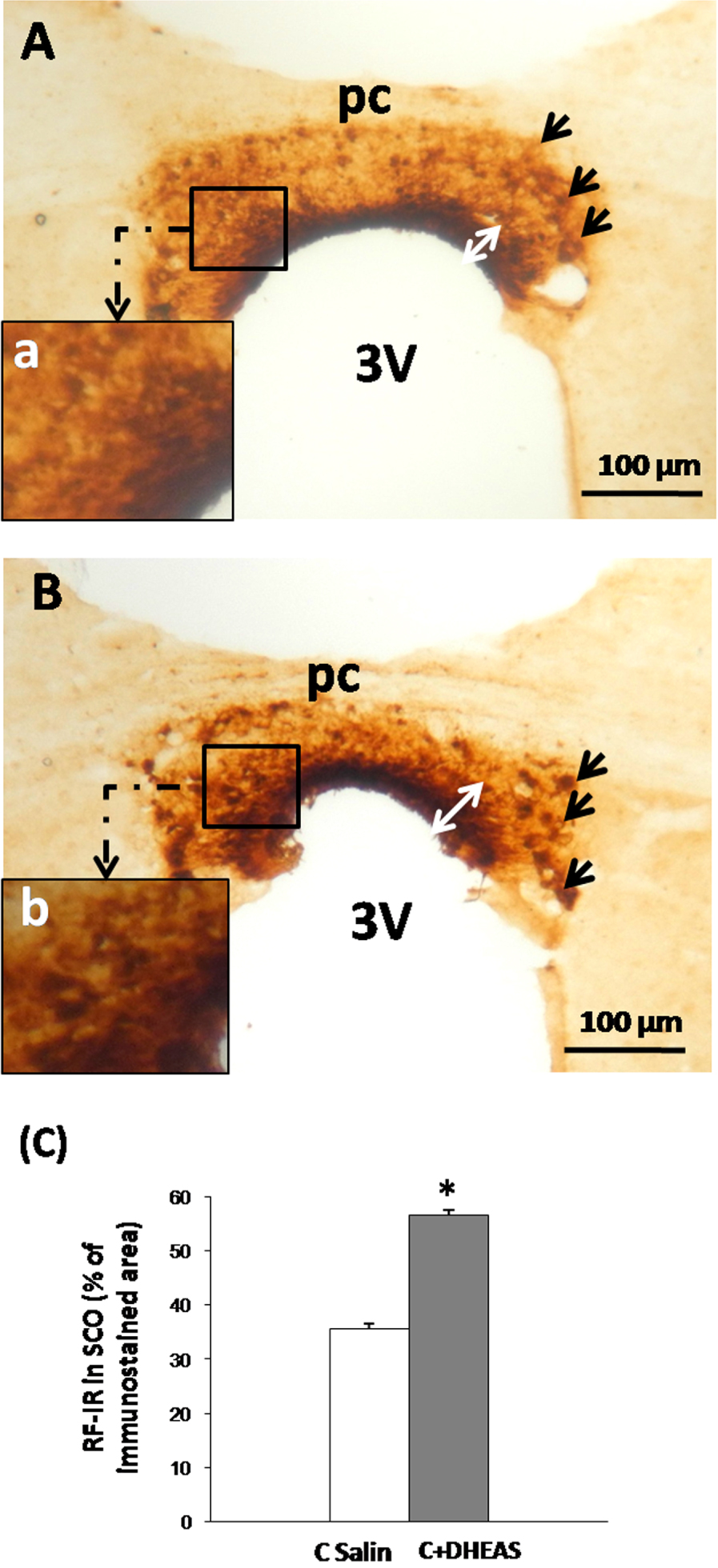

We performed immunohistochemical analysis using antiserum against Reissner’s fiber in frontal sections of the subcommissural organ. In saline controls, RF immunoreactivity appeared very important and extends into the entire SCO (Figure 1A). The labelling was observed on the three components of SCO: the ependymal cells, the hypendymal cells and the basal extensions that appear actively secreting with elevated RF-IR in the apical parts of the organ (Figure 1A,a). In DHEAS rats however, an overall and significant (Figure 1C, p < 0.05) increase in RF-immunoreactivity was observed throughout all parts of the SCO, especially the apical parts of the organ (Figure 1B,b).

Light micrographs of frontal sections through the subcommissural organ (SCO) of adult rat, immunolabeled with antiserum against Reissner’s fibers (RF). RF-immunoreactivity is spread throughout the SCO components in saline control rats (A), the immunolabeling is more obvious in the apical part of the organ (Aa). Administration of DHEAS triggers an increase in RF-immunoreactivity in all parts of the SCO (B) especially in apical part (Bb). (C) Histogram showing the density of RF-immunoreactivity of the SCO in both studied groups. Data are reported as mean ± SEM, and were subjected to Student t-test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance between groups. PC: posterior commissure, 3V: third ventricle, Aq: aqueduct of Sylvius.

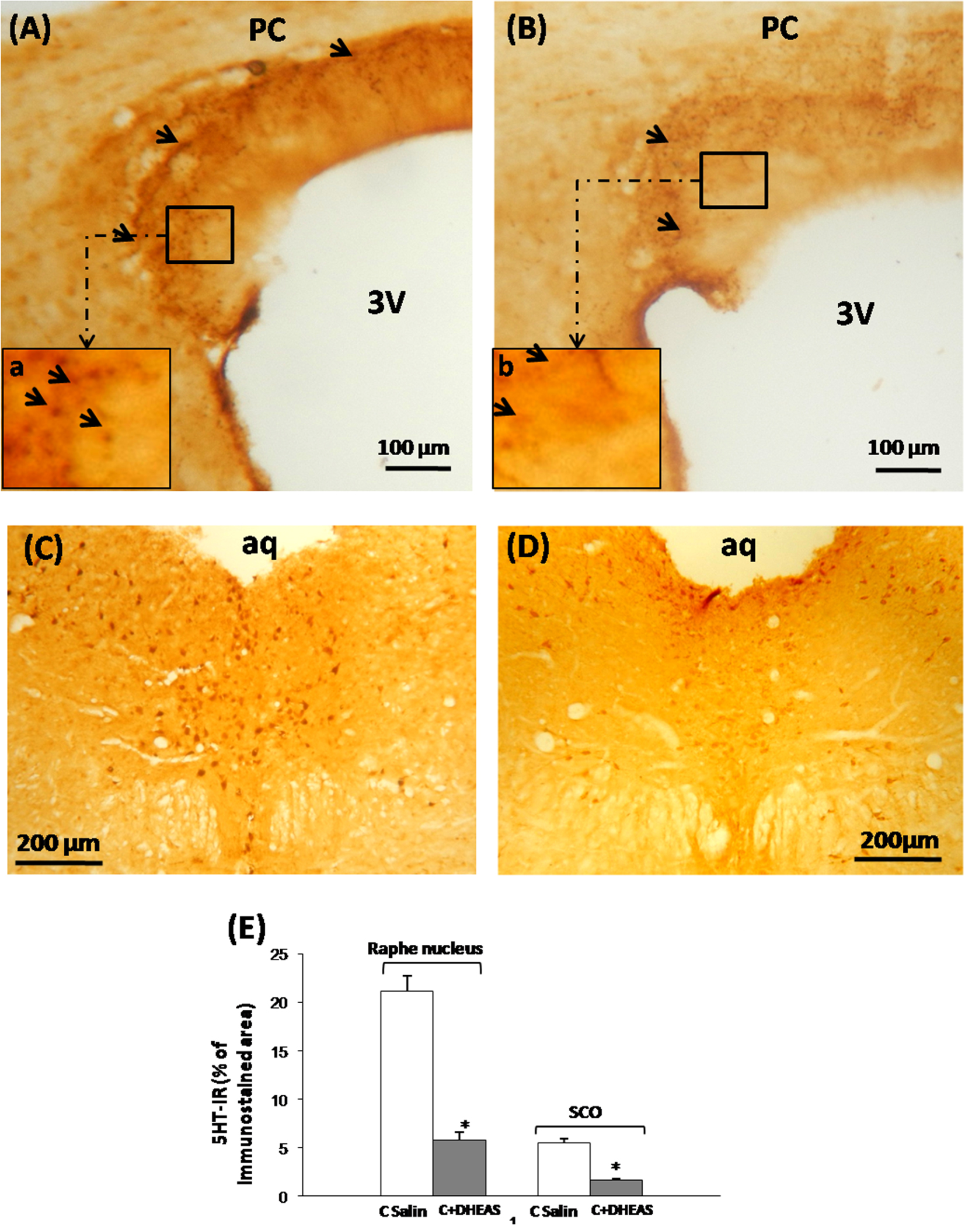

We performed an immunohistochemical assessment of serotoninergic innervation, well-known to control RF release by the different components of the SCO [34, 39, 41]. In saline control rats, we observed a dense and continuous plexus of 5-HT-immunoreactive fibers around the whole SCO (Figure 2A). The 5-HT-immunoreactive fibers were organized mainly on perpendicular and sometimes on parallel serotonin fibers reaching the ependymocytes and the hypendymal cells with a condensation at the lateral parts of the organ (Figure 2A,a). In DHEAS rats however, a significant (Figure 2E, P < 0.05) and obvious loss of the 5-HT-immunoreactivity was observed, especially within the basal and lateral parts throughout the SCO (Figure 2B,b).

Light micrographs of frontal sections throughout the subcommissural organ (SCO) (A, B) and the raphe nucleus (C, D) of adult rat immunostained with antiserum against 5-HT. The SCO shows numerous positive 5-HT fibers surrounding the organ forming a dense and continuous plexus of immunoreactive fibers surrounding the SCO with a condensation mainly in lateral parts (Aa). Treatment of rats with DHEAS (B), showed a drastic decrease of the 5HT-immunoreactivity in all SCO compounds (B). (E) Histogram displaying the percentage of 5-HT-immunoreactivity in the basal part of the SCO and the Dorsal Raphe Nucleus. Data are reported as mean ± SEM, and were subjected to Student t-test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance between groups.

To assess whether the loss of 5-HT in the terminal nerves reaching the SCO was related to events that happened within the perikarya of origin, we performed an immunohistochemical investigation of the nucleus of origin, the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN), which innervates different brain regions including the SCO [38, 44]. In DHEAS rat (Figure 2D), we observed a drastic loss of immunostaining in all regions of the DRN as compared to saline controls (Figure 2C), corresponding to significantly (Figure E, P < 0.05) diminished amounts of 5-HT in the perikarya as well as in the dendritic network of the whole nucleus.

4. Discussion

The modulator potential of neurosteroids, particularly dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its sulfate ester (DHEAS), upon multiple neuronal systems, has been mainly studied on the dopaminergic [20, 21], glutamatergic [22] serotonergic [19, 23] and GABAergic systems [24, 25]. Nevertheless, little is known about the glial responses to neurosteroids, except for some findings which have investigated the effects of neurosteroids upon astrocytes particularly [45, 46]. Through the present investigation, we aimed to evaluate the effect of in vivo administration in rats of DHEAS at a dose of 5 mg/kg, on RF release into the cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF) by SCO ependymocytes. The SCO is an ependymal gland located in the dorso-caudal region of the third ventricle, releasing glycoproteins of high molecular weight named “Reissner’s fiber” into the cerebrospinal fluid [26, 47]. This particular brain gland has been mainly described as one of the most recognized circumventricular organs (CVOs) in the mammalian brain [48, 49]. It constitutes a particular area of a deficient blood brain barrier characterized by a lack of tight junctions between endothelial cells [49]. Therefore it is highly permeable to molecules with high molecular weight and polar substances [49]. Numerous functions have been attributed to this particular organ which was implicated in different pathophysiological conditions (see introduction). However the mechanism of action involving this glycoprotein in such functions is still a subject of debate. After a single injection with the neuroactive neurosteroid DHEAS (5 mg/kg) in rats, we observed a noticeably increased Reissner’s fiber immunoreactivity within both the hypendymal and ependymal cells constituting respectively the basal and apical parts of the SCO. This led us to suggest a possible enhanced release of secretory material into the CSF and blood vessels [50]. To date, the functional significance of such a phenomenon is not yet established, although we speculate a possible RF regulatory role of monoamines levels and their metabolites in the CSF. Support of this view is provided by some substantial evidence showing that SCO-RF complex participates in the clearance from the CSF of certain monoamines by binding them. Thus, RF, either in vitro or in vivo, binds epinephrine (EP), norepinephrine (NEP), and 5HT [31, 37, 51]. The binding hypothesis has also gained support from recent molecular biology studies. RF-glycoproteins have repeated sequences [47] that exhibit a high homology with one or two domains of monoamine transporters [52]. These domains bind and transport along the CSF some monoamines and metabolites such as EP, NEP, dopamine (DA), 5-HT and L-DOPA [31]. Furthermore, rats devoid of RF had an increased CSF concentration of certain monoamines and their metabolites such as 5-HT, EP and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) [53]. These data further support the role of the SCO-RF in the clearance of brain monoamines reaching the CSF. Otherwise, considerable evidence has shown that DHEAS and DHEA elicit profound changes in the monoaminergic system. Indeed, in the presence of the dopamine D2 receptor antagonists, spiperone and sulpiride, DHEAS could produce a marked facilitation of the high K+-evoked [3H]NEP release in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, Monnet et al. [54] reported that DHEAS could potentiate NMDA-evoked release of [3H]NEP from hippocampal slices. Both DHEA and DHEAS have been shown to increase dopamine release, but under different experimental conditions. DHEAS (10-7–10-8 M) increases dopamine release in hypothalamic cell cultures [55] and PC12 cells [56]. DHEA also increases dopamine release in PC12 cells, but at earlier times than DHEAS [56]. Therefore, both DHEA and DHEAS increase dopamine release, but probably through different mechanisms. The above findings seem to support our view that RF is involved in the regulation of the possibly enhanced CSF levels of certain monoamines and their metabolites occurring in the brain supplemented with DHEAS.

Another evidence that may in part explain the rise of SCO-RF materials in the presence of DHEAS (our finding) is that the SCO is a target of numerous neuronal outputs, one of them of serotonergic nature [28, 34]. Indeed, our present findings have brought an experimental evidence of a loss of 5-HT immunoreactivity within the serotonergic fibers innervating the whole SCO after administration of DHEAS (5 mg/kg B.W). This was concomitant with a deficit within the nucleus of origin, the DRN. Otherwise, substantial evidence has suggested that the serotonergic system, which originates from the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN), controls negatively the SCO secretory activity in rat [28, 34, 57]. These data are in perfect concordance with our findings. Therefore the DHEAS-induced increased Reissner’s fibers contents in the SCO seems to be the eventual consequence of a down-regulation of 5-HT by the neuroactive neurosteroid DHEAS. Indeed, several effects of neurosteroids on serotonin metabolism have been elucidated in different experimental conditions. In fact, in the hypothalamus of B6 mice fed with a DHEA supplemented diets (0.45% w/w) for 7 days, 5-HT levels tended to decrease with its metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), suggesting reduced 5-HT synthesis [23]. Furthermore, DHEA (200 mg/kg, ip) increases 5-HIAA content in the midbrain and decreases 5-HT levels in the cerebellum [58]. At a dose of 25 mg/kg, it also increases 5-HIAA levels in the lateral hypothalamus (LH), ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) and the raphe, and augments 5-HIAA/5-HT ratio in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and raphe [20]. Those studies showed that DHEA and/or its metabolite androstenedione may both increase or decrease 5-HT synthesis and turnover at different doses and in different brain regions.

5. Conclusion

Through the present investigation we showed a particular effect of DHEAS on the secretory activity of the SCO as part of the circumventricular organs. The latter exhibited an evident increased secretory material spread to the entire SCO cells. Such increase in RF release by the SCO ependymocytes may involve a possible direct effect of the neurosteroid on the ependymocytes of the organ or an indirect modulation via the serotonergic system known to control the secretory activity of SCO. The functional significance of such a reaction is not fully established, although it may be involved in a possible RF regulatory role of monoamines and/or metabolites levels in the cerebrospinal fluid.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from PROTARS III D14/71. We also would like to thank CNRST-Morocco, CNERS Maroc, Morocco-Tunisian cooperation, IBRO, ISN and Neuromed for financial support.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0