1 Introduction

The emergence of ageing has been the subject of numerous questions in the past decades. The demographic statistics and their forecasts for the next century have shown that, in the developed countries, the number of older people will surpass those of the young and adolescents at around the year 2010.

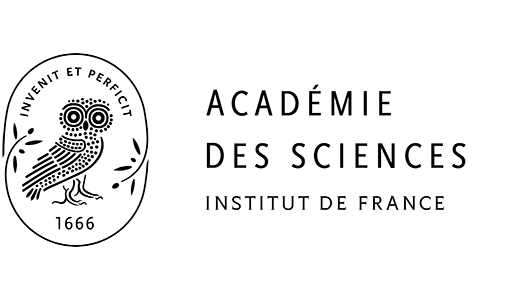

For example, the French ‘Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques’ (INSEE) has forecasted that in 2050, people at 65 years and older will represent 29.2% of the population, compared to 11.4% in 1950 (see Fig. 1) and that people under 20 years will be surpassed by the people over 60 years in 2001 〚1, 2〛.

Evolution of the French population (INSEE).

The emerging significance of public health issues associated with the ageing of the population has thus become of major importance.

According to INSEE, the life expectancy of people in their 60s was 20.0 years for men and 25.3 years for women in France in 1998.

The changing demographic pattern has increased the need for health promotion and provision of health care for this ageing population by an analysis of etiological factors affecting the health status of elderly adults and by an evaluation of potential medical interventions.

2 The diseases of ageing, and the geriatric conditions

Aged populations do not only suffer from specific diseases, but are also affected by geriatric conditions.

2.1 Cardiovascular diseases

The main specific diseases of old age are shown in Fig. 2 for the year 2000 as regards European mortality statistics 〚3〛.

The main specific diseases of old age in 2000 (from European mortality statistics).

However, some underlying causes of death are not stated in the mortality data, i.e. osteoporosis, which is responsible for numerous deaths due to hip fracture (only registered above as ‘injuries’) or dementia, leading to ‘other causes of death’; these are globally underestimated by mortality statistics.

The long list of major risk factors for cardiovascular diseases are: smoking, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, obesity, diabetes (which are considered the most prevalent diseases affecting older people) are not stated as causes of mortality. In reality, these risk factors are reflected by the high percentage of deaths due to cardiac problems and stroke, which concern, in around 85% of cases, people over 65.

However, some progress has been observed in the past decades and the causes of death of older Americans have evolved, due to a large decrease in death rates from cardiac and cerebrovascular conditions 〚4, 5〛 (Table 1).

Changes in mortality rates of older (aged over 65 years) adults due to selected diseases in the last half of the 20th century, USA.

| Cause of death | Age group (years) | Death rate (per 100 000 population) | % change | |||

| 1950 | 1970 | 1980 | 1995–1997 | 1950–1997 | ||

| Heart diseases | 65–74 | 1839 | 1558 | 1218 | 776 | –57.8 |

| 75–84 | 4310 | 3683 | 2993 | 2005 | –53.5 | |

| >85 | 9150 | 7891 | 7777 | 6329 | –30.8 | |

| Cerebrovascular diseases | 65–74 | 554 | 384 | 219 | 135 | –75.5 |

| 75–84 | 1449 | 1254 | 788 | 473 | –65.1 | |

| >85 | 2990 | 3014 | 2288 | 1610 | –46.1 |

It is estimated that 25% of the change in cardiovascular diseases are due to primary prevention of disease incidence, while 29% are due to secondary reduction of risk factors in patients with coronary artery disease and 43% are due to improvements in the treatment of the disease.

The influence of ageing of the population on cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality has been described by Kelly (Fig. 3) 〚6〛.

Influence of ageing on cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality.

It is thus important to look at the total disease burden rather than just its mortality, particularly with regard to cardiovascular diseases.

The effect of preventive strategies that could reduce the burden of morbidity and mortality due to cardiac and cerebrovascular diseases by small changes in the levels of some risk factors was calculated in the ‘Seven Countries Study’ and the results are given in Table 2 〚7〛.

Expected decline in all-cause mortality from arbitrary changes in mean levels of three risk factors.

| Cohort | Estimated change (%) in the percentage of all-cause mortality for small changes in risk factors levels | Estimated changes (%) in the percentage of all-cause mortality for large changes in risk factors levels |

| United States | –15 | –37 |

| Finland | –14 | –33 |

| The Netherlands | –10 | –23 |

| Italy | –13 | –30 |

| Croatia | –10 | –25 |

| Greece | –7 | –17 |

| Japan | –5 | –11 |

| Overall | –11 (CI: -8 and –14) | –25 (CI: -16 and –31) |

2.2 Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease

Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, in particular, will become one of the main causes of disability and of decreased quality of life among the elderly and their caregivers in the next 50 years 〚8〛.

On the basis of conservative prevalence estimates (assuming no reduction in the incidence of dementia as an increasing number of elderly people survive), the number of people with dementia in developed countries will increase from 13.5 million in the year 2000 to 36.7 million in the year 2050, with more than 9 million cases of Alzheimer’s disease just in the United States. By 2050, cases of dementia in the United States will approach the number of cases of cancer. The relationship between prevalence and age was found to be consistent across countries, with rates doubling every 5.1 years.

A very important consequence of the exponential rise in prevalence and incidence with age is that delaying the onset of Alzheimer’s disease by five years would decrease its prevalence by a half 〚9〛 (Fig. 4).

Effect of a five-year delay on the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Finally, some studies on the incidence 〚10〛 and prevalence 〚11〛 were used by the French Ministry of Health to calculate the burden of dementia in France in the year 2000. The global prevalence of dementia is estimated to be of 435 000 people (4.45% of the 65 and over) in 2000, of which 70% will be of the Alzheimer type, 10% of the vascular type and 20% of the mixed type. The incidence (new cases diagnosed every year) is estimated to be around 100 000 for Alzheimer’s disease, of which two thirds occur in people over 79. Finally, according to some hypotheses concerning forecasts of population and mortality, a hypothesis of the number of people affected by dementia could be 1 099 000 cases in 2020 in France 〚12〛.

2.3 Geriatric conditions

Maintenance of health in the elderly is not only, strictly speaking, a medical problem, but also a question of reducing disability and impaired daily living functions.

The usual ‘geriatric conditions’ such as falls, urinary incontinence, frailty, hearing and visual impairment could be prevented, and both primary and secondary preventions are effective.

Chronic diseases, geriatric conditions, psychosocial and economic status, health habits and availability of some forms of coverage for impaired aged people are the main factors that play a role in ‘healthy’ ageing.

However, the level of dependency in elderly people is only 12% of those over 60 as being really in need of a daily help.

In a study by INSEE and by the Ministry of Social Affairs in France, the levels of dependency were evaluated (Fig. 5) 〚13〛.

Levels of dependency of people over 60 years.

It is important, in fact, that the increase in life expectancy be associated with disability-free years of life, rather than with more years of life with disability.

Similarly, maintenance in some functions/activities (primary prevention) has proven to be more effective than an improvement after the disability has occurred 〚14〛. Some of the diseases affecting mainly older people offer the opportunity for prevention of recurrent events as well as subsequent incidents: myocardial infarction, stroke... Some other diseases like cancer, osteoporosis, dementia, prostate problems, develop in a more progressive fashion and diagnosing them as soon as the ‘preclinical’ phase can significantly improve the quality of life until death.

Finally, the rapidly expanding proportion of the population 65 years and older is anticipated to have a profound effect on health care expenditures. The relationship between functional status and MEDICARE–MEDICAID health care services in the USA has been calculated on a longitudinal cohort study of persons 72 years or older 〚15〛.

The 19.6% of elderly people who had stable functional dependence or who declined dependence, accounted for 46.3% of total expenditure (hospital + home-care + nursing home services). People in these groups had an excess of $10 000 in expenditure in two years compared with those who remained independent. The 9.6% of patients who were dependent at baseline accounted for more than 40% of home health and nursing home expenditures; the 10.0% who declined accounted for more than 20.0% of hospital, outpatient and nursing home expenditures.

3 Research strategies for ageing

3.1 Ageing consumer and health

As already stated, ‘compressing’ morbidity and disability, to help people at the age of 65 with 15–20 years of additional life expectancy, to remain robust and active until the last years of life, is one of the main objectives of research on ageing. Screening strategies and prevention that target the identification of people with ‘preclinical’ changes are more effective in preventing morbidity and disability effects. It must be stressed, however, that approximately 50% of severe disability in older adults occur progressively and 50% occur acutely as a result of events such as hip fracture, stroke, injury, and myocardial infarction... In addition, the probability of recovery is decreasing with increasing age as regards the condition. Even if consumption of drugs is not the unique answer to such a situation, some benefits of drugs have been calculated which show a significant effect on mortality.

For example, the impact of major therapies on the reduction of mortality in acute myocardial infarction was calculated from 1975–1995 in the USA (Table 3) 〚16〛.

Benefit from major therapies for acute myocardial infarction, 1975–1995.

| Medications | Increase in use (in%) | Reduction in mortality explained (in%) |

| Aspirin | 70 | 34 |

| Betablockers | 29 | 7 |

| Thrombolytics | 31 | 17 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 24 | 3 |

| Primary angioplasty | 9 | 10 |

| TOTAL | 71 |

The pharmaceutical expenditures should be put in perspective with the total health care consumption, and the following data from the French INSEE show that pharmaceutical costs represent a small part of the total of health care costs and of the gross domestic product (Table 4) 〚17〛.

Evolution of the part relating to pharmaceutical consumption in the Gross Domestic Product (France) in million FF.

| Year | Gross domestic product | Total medical care and goods consumption | % of GDP | Pharmaceutical consumption | % of GDP |

| 1970 | 793 519 | 41 432 | 5.2% | 10 730 | 1.35% |

| 1975 | 1 467 884 | 92 009 | 6.3% | 20 256 | 1.38% |

| 1980 | 2 808 295 | 192 327 | 6.8% | 33 687 | 1.20% |

| 1985 | 4 700 143 | 364 933 | 7.8% | 64 200 | 1.37% |

| 1990 | 6 509 500 | 528 401 | 8.1% | 96 125 | 1.48% |

| 1995 | 7 662 391 | 681 964 | 8.9% | 126 325 | 1.65% |

| 1996 | 7 860 517 | 701 401 | 8.9% | 129 355 | 1.64% |

| 1997 | 8 137 085 | 712 737 | 8.8% | 134 400 | 1.65% |

Previously, the patient was essentially passive but the current reality is that the ageing population is healthier and better educated than ever before, and financially more secure: 60% are neither disabled nor dependent. The future ‘aged’ consumer is now becoming an ‘empowered’ customer: the baby-boomers are accustomed to freedom of choice, to take responsibility of cost-sharing with health and they want more health information and awareness. The patients are becoming lobbyists (for example cancer patients in the USA) and, even if the consumer does not choose directly the pharmaceutical product, which is chosen by a prescriber, he has some influence through the information he has received/searched.

Prescription-drug therapy reduces treatment costs by controlling symptoms, alleviating pain, reducing necessity of hospital stays and of nursing care. However, the senior patient has still some reluctance to ask his doctor for advice or help as regards diseases typical of the aged population (Fig. 6) 〚18〛.

Percentage of senior citizens (≥ 65 years) with disease symptoms yet not visiting the doctor.

It is noticeable that information on some pathologies, notably under-diagnosed and poorly treated (hypertension, depression, atherothrombosis...) is lacking and a great effort is needed to supply this information not only to health care providers but also to the final consumer.

3.2 Pharmaceutical R & D

The response of the pharmaceutical industry to the increasing demand for the well-being of the aged consumer is research.

According to a recent survey of the Pharmaceutical Research Manufacturers Association in October 2001, 785 drugs in the USA were in development for the diseases affecting ‘older’ Americans and, in USA only, 120 pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies were involved in such research 〚19〛.

The innovation that has made old age possible has increased the cost of pharmaceutical research and development by two to three times in the past decades (Fig. 7).

R&D pharmaceutical costs: Europe, USA and Japan (sources: EFPIA, PhRMA, JPMA).

The major growth of R&D expenses has not been slowed down by the cost containment policies observed in countries.

Drugs are ‘goods’ under protection with strict regulatory procedures for pricing and for marketing. Health is usually regarded as a social cost rather than a social benefit and imbalance of the social budget has reinforced rigor in the politics for health expenses, leading to recent new characteristics of R & D in the pharmaceutical industry.

The successful introductions of new pharmaceutical products are the result of three new characteristics of R & D:

- • new innovation processes/research strategies;

- • birth of new actors and networks connecting them;

- • increasing regulations in the development process.

3.3 New innovation processes/research strategies

The innovation processes in pharmaceutical research remain somewhat ‘chaotic’, although they could be classified as follows:

- • molecular approach (chemical or molecular analogues of an already marketed compound or compound in late pre-clinical or clinical development; for example, dronedarone, an antiarrhythmic agent chemically related to amiodarone with an excellent pharmokinetic profile – no accumulation – and an excellent safety profile);

- • new formulations that increase observance and compliance to treatment, especially in older people; one such example is the invention of patches, but a lot of companies are working on the ‘ideal’ formulation that is a once-a-day oral administration (in case of such a formulation for insulin, for example, the treatment of diabetes could involve a lot of people previously untreated today);

- • biotechnology products (a lot of expectations were put in biotechnology 10 years ago, and some successful products (thrombolytics, human growth hormone, erythropoietin) show that these expectations were founded; however, pharmaceutical industry is currently overflowed with the data associated with this technology and the current question is to translate the mass of information collected into relevant new chemical entities);

- • physiopathological approach, which validates a biological mechanism and allows to identify a new site of action, has proven effective in the treatment of venous thrombosis with heparin (after characterising the sequence of the heparin moeity responsible for its anti-coagulant activity, the chemical synthesis of a fragment of five sugars resulted in a pentasaccharide compound, fondaparinux, with potent anti-thrombotic activity);

- • exploratory approach (the discovery of new targets that one suspects of playing a role in certain pathologies; one has then to find drugs that inhibit the enzyme or stimulate/antagonise the receptor and establish the most relevant therapeutic indication; for example, Rimonabant (SR 141716) – the first potent and selective antagonist of the central cannabinoid receptor (CB1) for the treatment of obesity);

- • genomics and proteonomics, leading to pharmacogenomics, have given the opportunity of better selecting responders to drugs (the deciphering of the human genome makes it possible to identify the genes responsible for certain diseases; it is therefore possible to establish differences between a healthy and a diseased tissue, and we can thus identify new biological targets upon which medicines can act).

Some benefits of pharmaceutical research can be put in perspective for diseases of aged people:

- • new basic science investigations have elucidated the mechanism of action of alpha-adrenergic receptor antagonists used first in hypertension and now shown to be active in benign prostate hyperplasia;

- • ‘translated’ research has identified new uses of a given mechanism of action, for example the cardiovascular benefits of aspirin;

- • clinical practice and ‘post-marketing’ discoveries identify new uses of a drug either in clinical trials or at the bedside 〚20〛 and the full benefits of some technologies frequently emerge only once they are introduced into clinical practice; secondary indications have been estimated to account for 25 to 40% of the sales of the top selling products in the UK and in the USA, respectively 〚21〛.

3.4 Birth of new actors and networks connecting them

Recent developments in the research into health and diseases have involved the emergence of new actors: biotechnological companies, public R & D centres (or financed by public funds, like GENETHON) working on specific diseases and not only on basic sciences, as well as contract research organisations working on very specific targets. It has been observed, in last ten years, that pharmaceutical companies have externalised entire sections of R & D activities to specialised companies: 30% of the R & D budget of the top-ten pharmaceutical companies relates to external/outside research in 2000, against 4% in 1994.

Industrial and marketing technological networks connecting these different actors have changed the classical ‘frontal rivalry’ into cooperation and even integration/collaboration between pharmaceutical firms 〚22〛.

3.5 Regulations increasing in development process

The clinical trial phases of a new drug are the longest part in the development process and they are not always successful. It has been estimated the clinical success rate for new drugs is very restricted: one in 1 000 drug candidates progresses to clinical trial 〚23〛. Of 100 drugs entering clinical trials, about 20% are approved for marketing, with 30% rejected at phase I, 37% at phase II, 6% at phase III, and 7% at regulatory levels.

Some experts from the Tufts Centre 〚24〛 have evaluated the costs of a new drug development at $ 802 million.

- • The full-capitalised resource cost of new drug development was estimated to be $ 802 million (for the year 2000). This estimate accounts for the cost of failures, including research on compounds abandoned during development, as well as opportunity costs of incurring R & D expenditures before earning any returns.

- • When compared to the results for previous similar studies, the R & D cost per approved new drug increased 2.5 times in inflation-adjusted terms, over the 10 year-period between 1991 and 2001.

- • After adjusting for inflation, the out-of-pocket cost per approved new drug increased at a rate of 7.6% per year between the 1991 study and the 2001 study. The annual rate of growth in capitalised cost between the two studies was 7.4% in inflation-adjusted terms.

- • While costs have increased in inflation-adjusted terms for all R & D phases, the increases were particularly acute for the clinical period. The inflation-adjusted annual growth rate for capitalised clinical costs (11.8%) was more than five times greater than that for pre-clinical R & D.

The clinical trials are, by far, the most expensive part of costs of drug R & D: according to Center Watch, a listing service for clinical trials 〚25〛:

- •

the number of clinical trials performed in the USA were

- ◦ 14 000 in 1980

- ◦ 33 000 in 1990

- ◦ 60 000 in 1998;

- •

the mean time in the clinical testing phase of drug development was

- ◦ 5.5 years in the 1980’s

- ◦ 6.7 years in the period 1990–1996;

- •

the mean number of patients involved in each new drug application was

- ◦ 3 567 in 1989–1992

- ◦ 4 237 in 1994–1995.

Clinical trials have, in fact, interrelated, but competing demands:

- • recruitment of large numbers of patients (statistical power, safety);

- • long-term trials due to ageing;

- • careful selection of participants to obtain meaningful results 〚25, 26〛.

In fact, clinical trials are now performed more and more within the elderly population. This is in relation to the treatment of specific diseases of the geriatric population, i.e., Alzheimer’s Disease, but also to evaluate the effects of all new treatments, as the elderly population sector is considered as a specific target area of drug evaluation; thus, elderly patients should be evaluated for all new potential treatments as well as the normal age range of patients.

Finally, health authorities have reduced their approval time so as to put, as early as possible, new drugs on the market 〚26〛.

In recent years, the number of N.C.E.S approved by the US FDA has increased considerably:

- • from 1987 to 1993, 24 N.C.E. (on average) per year;

- • from 1994 to 1999, 35.5 N.C.E. (on average) per year;

- • from 1987 to 1993, mean approval time, 26.3 months;

- • in 1999, mean approval time, 12.6 months.

4 Conclusions

The present research strategies for ageing focussed around three areas.

4.1 Demographic study of the present-day populations and of those in the future

The analysis of the evolution of the metropolitan French population from 1950 to 2050 indicates that the proportion of subjects aged 60 years and over will pass from 16% to 35% 〚2〛.

4.2 Integration of epidemiological data in the pathologies related to the aged subjects

Numerous epidemiological and sociological studies of the aged show that the elderly population is in better health, better informed about the diseases that affect them and also financially more secure.

4.3 The important progress in the understanding of the biological mechanisms involved in cellular ageing

The recent progress in the area of cellular biology has started to decode the complex mechanisms underlying cellular ageing. The important understanding of the phenomena of apoptose with the development of relevant biological models of the natural ageing process have anticipated future treatments and, eventually, the prophylactic treatment of specific pathologies of the elderly patient.

The adaptability of the industry has been done by:

- • increasing the R & D budgets by taking greater financial risks 〚24, 27, 28〛;

- • attaining the critical size in R & D (mergers-acquisitions, alliances between private companies that reduce the duplication of the research effort);

- • adoption of new methods in R & D;

- • becoming exclusively pharmaceutical (selling off of agrochemical activities, restraining oneself to a limited number of R & D domains/interests, ‘core activities’, rather than evaluating new potential areas);

- • increasing the capacity to anticipate new potential markets (prospective studies, scientific and competitive intelligence).

Finally, the pharmaceutical companies that will cope better with the problem of age will be those that have the competence and the resources to discover and then develop the increasingly breakthrough compounds, focused on the unmet medical needs of an increasingly ageing population.

Version abrégée

Le vieillissement de la population est un phénomène inéluctable, qui pose à tous les pays industrialisés des problèmes économiques et sociaux, et tout particulièrement de santé publique. Pour ce qui concerne la France, l’Insee a annoncé que, dès 2001, le nombre des plus de 60 ans dépasserait celui des moins de 20 ans. Actuellement, à cet âge, l’espérance de vie est supérieure à 20 ans, pour les hommes, et à 25 ans, pour les femmes, en France.

Les « seniors » constituent la partie de la population qui est la plus touchée par certaines pathologies : cardiovasculaires (infarctus, insuffisance cardiaque), neurologiques (démences), cérébro-vasculaires ( accident vasculaire cérébral), du système ostéo-musculaire (arthrose, ostéoporose) et cancers.

En fait, le poids de ces pathologies s’exprime, non seulement en termes de mortalité, mais aussi en termes de dépenses sociales, de journées d’hospitalisation et de séjours en gériatrie, de consommation de soins et de médicaments et, enfin, de perte de la qualité de vie, tant pour les personnes âgées que pour leur entourage. On constate donc que de nombreux travaux d’épidémiologie sont actuellement réalisés, qui devraient permettre de mieux appréhender le poids des pathologies des personnes âgées sur le système de santé et les dépenses de soins.

Ainsi, la maladie d’Alzheimer et les autres démences séniles, qui affectent actuellement en France 435 000 personnes, pourraient toucher, en 2020, plus d’un million de personnes, selon certaines estimations récentes. Cependant, si l’on arrivait à retarder de cinq ans le délai d’apparition de la maladie, on diminuerait sa prévalence par 2.

D’autres études ont montré que, de 1975 à 1995, 60% de la réduction de la mortalité due à l’infarctus du myocarde était imputable à l’utilisation de quatre grandes classes de médicaments : les anti-agrégants plaquettaires, les thrombolytiques, les bêta-bloqueurs et les inhibiteurs de l’enzyme de conversion de l’angiotensine.

La prévention des pathologies du sujet âgé doit être non seulement secondaire (prévenir les récidives) mais également primaire (réduire le nombre et/ou l’intensité des facteurs de risque afin d’éviter ou de retarder la survenue de la maladie) et la précocité de l’intervention est le gage de son succès. Si les personnes âgées sont les premiers consommateurs de soins, elles sont également de mieux en mieux informées sur les pathologies et les divers moyens de les prendre en charge. Les personnes âgées sont également, dans leur ensemble, des consommateurs plus avertis, ayant la possibilité financière de prendre en charge leur santé.

Une vieillesse sans handicap la plus longue possible est, depuis des décennies, un objectif majeur de la recherche dans le domaine de la santé et, plus particulièrement, de la recherche dans l’industrie pharmaceutique.

Les moyens de prévenir, comme de traiter, les maladies spécifiques aux personnes âgées font en effet l’objet d’une intense recherche, tant dans les organismes publics que dans l’industrie. De nouvelles stratégies de recherche se sont mises en place au cours de ces dernières années, qui devraient voir leur efficacité confirmée dans le futur, pour mettre au point des traitements mieux adaptés aux pathologies liées au vieillissement.

La recherche de nouveaux produits plus efficaces ou plus ciblés se fait selon diverses approches, toutes actuellement mises en œuvre en parallèle par l’industrie pharmaceutique : les biotechnologies et la recherche sur le génome offrent actuellement de très larges perspectives, bien qu’à l’heure actuelle, peu de nouvelles molécules en soient déjà issues. L’augmentation des connaissances pathophysiologiques et biologiques, ainsi que la recherche exploratoire, ont permis d’identifier de nouveaux sites d’action, des récepteurs sur lesquels il est possible de mieux cibler des produits à la fois plus actifs et ayant moins d’effets indésirables. Enfin, l’observation, lors de l’utilisation en grandeur réelle, de certains médicaments, a permis, soit d’en découvrir de nouvelles indications, soit de construire des molécules voisines chimiquement.

Toutes ces méthodes de recherche ont eu pour effet d’allonger considérablement l’espérance de vie en bonne santé, mais il apparaît cependant que nombre de maladies spécifiques aux personnes âgées sont encore peu ou mal diagnostiquées et mal prises en charge. On pourrait citer l’hypertension, l’athérothrombose, mais aussi les cancers, qui ne sont pas encore dépistés assez tôt.

Ces nouvelles voies de recherche ont cependant un coût élevé. Ainsi, en 2001, un organisme américain a évalué à 800 millions de dollars (environ 920 millions d’euros) le coût de développement d’une nouvelle molécule. Ce coût élevé prend en compte les échecs de la R&D. On sait en effet que, sur mille nouvelles entités chimiques, une seule arrivera jusqu’aux essais cliniques. De même, sur cent produits qui rentrent en essai clinique, seuls 20% seront mis sur le marché.

Les études cliniques représentent la partie à la fois la plus longue et la plus onéreuse de la mise au point d’un médicament. Et pourtant, leur nombre a été multiplié par quatre aux États-Unis entre 1960 et 1998. Des sommes considérables ont été investies : en 1999, on estime que l’industrie pharmaceutique européenne a dépensé en frais de R&D 15 000 millions d’euros et l’industrie américaine 18 800 millions d’euros, et l’on estime que les coûts des essais cliniques ont augmenté de 12% par an entre 1990 et 1999.

Afin de rentabiliser au mieux l’effort financier de recherche, les différents acteurs de l’innovation dans le domaine de la santé ont créé entre eux des réseaux toujours plus nombreux et plus actifs, qui relient la recherche fondamentale et la recherche appliquée, les organismes publics et les entreprises privées. Ainsi, de très nombreuses collaborations se sont mises en place entre l’industrie pharmaceutique et des sociétés de biotechnologie. Il en est de même avec les organismes de recherche publique.

Par ailleurs, des sociétés spécialisées dans des secteurs particulièrement pointus de certains aspects de la R&D pharmaceutique apportent leur contribution à l’effort de recherche. On peut estimer au total que, sur les dernières années, 20% du budget de R&D pharmaceutique a été investi dans des collaborations avec des sociétés spécialisées.

Il est cependant évident que la recherche sur les pathologies du vieillissement devrait entraîner une augmentation du nombre de chercheurs impliqués dans cette recherche, mais aussi de ses coûts. On assiste à une augmentation croissante du nombre moyen de patients inclus par essai (environ 4500 patients par essai en 1995), afin d’obtenir les résultats les plus significatifs possibles. L’allongement de la durée de ces mêmes essais, en particulier pour tout ce qui se rapporte à la prévention des facteurs de risque ou de survenue d’une pathologie, est nécessaire. Par exemple, pour vérifier si un nouveau produit retarde la survenue d’une maladie d’Alzheimer, il est nécessaire de suivre des patients pendant cinq, voire huit ou dix ans.

Les essais cliniques sont de plus en plus orientés vers des patients beaucoup plus âgés que la population générale, qui était auparavant celle qui rentrait en priorité dans ces essais. Les délais de mise sur le marché de produits plus efficaces se sont donc rallongés. Enfin, les exigences de sécurité sont à la base de nombreuses études dès les premières phases de la recherche, et ce jusqu’à l’utilisation du produit dans le monde entier.

En conclusion, une meilleure compréhension des différents mécanismes impliqués dans les pathologies du vieillissement a déjà permis de mettre au point des traitements préventifs et curatifs spécifiquement adaptés aux pathologies des personnes âgées. On a vu récemment l’intérêt provoqué par les résultats des recherches dans le domaine de la biologie cellulaire du vieillissement et de l’étude des mécanismes d’apoptose. L’industrie pharmaceutique a mis en œuvre de nouvelles méthodes de recherche et développement. Elle a noué de nouvelles relations avec différents acteurs de la santé publique. Elle s’est recentrée sur ses domaines d’excellence afin de devenir plus efficace. Enfin, elle a pris des risques financiers considérables en augmentant ses budgets de recherche et développement. Les résultats combinés de toutes ces stratégies devraient lui permettre, à terme, de mieux répondre à tous les besoins médicaux que ne le laissent envisager l’évolution démographique et le souhait de plus en plus ouvertement formulé de profiter de l’allongement de l’espérance de vie dans les meilleures conditions de santé possibles.