1 Introduction

Montecristo is a small island (10.39 km2) and is part of the Tuscan Archipelago in the northern Tyrrhenian Sea (Italy); it is located between Monte Argentario (southern Tuscany) and Corsica Island (France) (Fig. 1). From a geomorphologic point of view, this island is peculiar in composition and shape; it is completely composed by granite, and its profile is conical with 645 m of maximum elevation from sea level (Fig. 2A). Even if some traces of Neolithic human settlement were found, the first civilizations that arrived in the small rocky inlets were the Etruscans, to harvest oak wood, and later the Romans to extract granite; these called the Island Oglasa, meaning yellow peak [1]. Relative to its neighboring islands of the Tuscan Archipelago, Montecristo was subject to limited human impact. In more recent times, history and legends fused together and the island was a centre of interest for pirates, treasures, dragons, and saints [1,2]. The naturalistic value of Montecristo Island was recognized in 1970 and it was given protection in 1971 (Riserva Naturale Biogenetica), part of the Tuscan Archipelago National Park, and in 1988 the European Community also recognized it as an important natural reserve. Five people live in the only house on the island and only 1000 people can visit the island each year. The coastal environments of Montecristo are also protected by a 1-km boundary around the island, in which entry without a permit is prohibited (Corpo Forestale dello Stato: http://www.corpoforestale.it). Montecristo may appear homogenous at first sight; however, the island is rich in streams and supports several microhabitats. Montecristo experiences the lowest temperature excursions in the Italian Peninsula, ranging between 14–16 °C, and the island receives 600 mm a year of rainfall. From a climatic point of view, Montecristo Island is described as a temperate–warm area [3], with high inclination and limited presence of soil. The vegetation is predominantly characterized by low maquis and garigue, composed by shrubs such as Erica scoparia, Rosmarinus officinalis and Cistus salvifolius [4]. Few trees are present on the island and the only autochthonous ones are very old oaks (Quercus ilex) (Fig. 2D), prevalently concentrated in the locality of ‘Collo dei Lecci’, a small area at ca. 400 m a.s.l. Moreover, a small pine wood (Pinus pinea, P. halepensis) was planted in Cala Maestra (Fig. 2B and C). Among the many fascinating aspects of this island, the fauna is one of the most evident. Some studies have been conducted on mammals [1], birds [5,6], and reptiles [7], but most discoveries resulted from the observation of the biodiversity of invertebrates, including both meso and macro fauna: Collembola [8], Acari (Oribatida) [1,9], Coleoptera [10–12], Copepoda [13], Isopoda [14,15], terrestrial gastropods [16,17], planarians [18], and spiders [19].

Map showing the Tuscan Archipelago with its seven Islands, and Montecristo Island's map.

Montecristo Island (A) and the coast front off Cala Maestra (B). The pine wood of Cala Maestra (C) and a dead oak at the locality of ‘Collo dei Lecci’, 400 m a.s.l. (D).

Di Caporiacco [20] was the first who studied the scorpions of Montecristo; he pointed out their extreme olygotrichy and their peculiar color pattern. On the basis of these observations, he created the subspecies: Euscorpius carpathicus oglasae; later, few considerations were given by Valle [21]. During the next three decades, this taxon was mentioned by some authors [21–30], but again taken in due consideration and included into a morphological study regarding the Euscorpius carpathicus complex only in 2002 (Fet and Soleglad). Fet and Soleglad analyzed Di Caporiacco's 13 type specimens and also observed the low number of trichobothria on the external (series et) and ventral surface of pedipalp patellar surface and designated one lectotype and two paralectotypes, and synonymized E. c. oglasae with Euscorpius (Euscorpius) tergestinus (C.L. Koch, 1837). This species received very little attention after its description compared to other Mediterranean euscorpiids and this is probably due to the difficulty to obtain and observe specimens, owing to the island's isolation and the strict laws that regulate collecting there. Two recent trips have been organized to obtain a larger sample of specimens, some of which were also analyzed using molecular techniques for the first time. Preliminary results of the molecular analysis evidenced a high genetic divergence compared to other similar Italian taxa [31]. We present here a thorough morphological study, including comparisons with other closely related taxa. Euscorpius c. oglasae is redescribed, illustrated and elevated to species rank.

2 Material and methods

A total of 35 specimens of E. c. oglasae were analyzed (see § Material examined). Specimens were collected during day-time searches under stones and bark, and preserved in 75 or 95% ethanol; these samples are in the collection of V.V. (VVZC) in the Department of Evolutionary Biology, University of Siena, Italy. The collecting on the island followed a selective criteria limit impacting on the population. We also examined eight specimens from the collection of the Museo di Storia Naturale di Bergamo ‘E. Caffi’ (MCSNB). The 13 syntypes of Di Caporiacco, from the Museo Zoologico ‘La Specola’ (MZUF), Florence (13 specimens) are not included in this study because loaned in present time to V. Fet, Marshall University (USA), and were not available for our study at the time of writing. For biometric analysis, on each specimen, 26 measurements (appropriate to investigate biometric differences between similar morphotypes) were taken following Fet and Soleglad [24] and ten adult specimens, five males and five females, were randomly selected and the measurements were added to the dataset used in Vignoli et al. [29]. Mensurations (all in millimeters) follow Stahnke [32] and were made with an eye piece graticule. Morphological nomenclature follows Vachon [33], Hjelle [34], Soleglad and Sissom [35], Sissom [36] and Jacob et al. [37]; sternum terminology follows Soleglad and Fet [38]. Digital photographs, which show details and morphological features, were acquired with an Olympus CAMEDIA C-4040 mounted on a stereomicroscope Olympus SZX12, while other images were taken with a Pentax S50. Hemispermatophores were dehydrated, and sputter-coated, with the spattering Blazer CPD 030, and scanning electron micrographs were taken from selected specimens stored in 75% ethyl alcohol with a Philips XL 20 scanning electron microscope (SEM). Locality data were recorded with a portable Garmin GPS. Abbreviations: juv.: juvenile; imm.: immature; : total number of trichobothria on patella ventral surface; : total number of trichobothria on patella external surface; DPS: dorsal patellar spur; : pectinal tooth count; L: left; R: right; lb: basal lobe; lde: outer distal lobe; ldi: inner distal lobe; : telson vesicle length; : telson vesicle depth; : carapace length; : hemispermatophore length. MCSNB: Museo Civico di Scienze Naturali ‘Enrico Caffi’, Bergamo, Italy; MNHN: ‘Museum national d'histoire naturelle’, Paris, France; MZUF: Museo Zoologico ‘La Specola’ dell'Università di Firenze, Florence, Italy; VVZC: Valerio Vignoli Zoological Collection, Siena, Italy.

Comparison material observed:

- • Euscorpius carpathicus apuanus Di Caporiacco, 1950: two females (syntypes, MZUF 125/5938–5945), Monte Corchia, Vallecchia, Pietrasanta, Levigliani, Apuan Alps, Lucca (LU), Tuscany, 03.VIII.1875, Del Prete & G. Cavanna coll.;

- • Euscorpius carpathicus corsicanus Di Caporiacco, 1950, Corsica, France, (MZUF: 1 specimen): 1 male, (MZUF-1168), Grotte di Sisco, 11.IV.1977, B. Lanza coll. (VVZC: 17 specimens): 3 females (Eut614–616), Calanchi di Piana, Piana, Porto, N42°, E08°, 421 m, pine forest, 12.II.2006; 2 females (Eut618–619), between Sisco and Marina di Sisco, Bastia, Cap Corse, N42°, E09°, 124 m a.s.l., oak forest, 11.II.2006; 1 juv. (Eut620), Sisco, Bastia, Cap Corse, N42°, E09°, 238 m oak forest, 12.II.2006; 3 males (Eut621–623), 5 females (Eut624–228), 2 juv. (Eut629–630), between Solenzara and Zonza, Porto Vecchio, N41°, E09°, 109 m a.s.l., pine forest, 12.II.2006, V. Vignoli & F. Cicconardi coll.;

- • Euscorpius carpathicus niciensis (C.L. Koch, 1841) (MNHN: 61 specimens): 7 females, 2 juv., 1 male (RS 5330), Saint-Paul-de-Vence (Alpes-Maritimes), III.1970, M. Willaume coll.; 9 males, 2 females (‘Entrée’ No. 4, 1972), Trans-en-Provence (Var), 5 km from Draguignan, 14.XII.1970, M. Willaume coll.; 1 juv., 5 females, 4 males, Roquefort-des-Pins, Alpes-Maritimes, 08.I.1970, M. Willaume coll.; 19 females, 3 males, 7 juv. (RS 3722), St. Beaume, Sospel, Nice (no data and coll. specified);

- • Euscorpius balearicus Di Caporiacco, 1950 (MNHN: 92 specimens, VVZC: 1 specimen; Majorca, Spain): 2 juv., 30 females (RS 7935), Sóller, tour Picada, VI.1975, E. Frèchin coll., ‘Entrée’ No. 11; 26 males (RS 7818), 35 females (RS 7815), Sóller, VI.1974, pine forest, E. Frèchin coll., ‘Entrée’ No. 45; 1 female (VVZC-173), VIII.2001, J. Ove Rein coll.;

- • Euscorpius concinnus (C.L. Koch, 1837), Euscorpius tergestinus s.s. (C.L. Koch, 1837) (‘red’ morphotype in Vignoli et al. [29] (VVZC: 167 specimens): see Vignoli et al. [29] for details.

3 Systematics

Euscorpius oglasae Di Caporiacco, 1950, stat. nov. (Figs. 3–4; Table 1)

Telson of adult female (A) and male (B); external view of pedipalp chela, male (C), female (D); external surface of pedipalp patella (E) (trichobothria are surrounded by white circles); ventral and dorsal surface of pedipalp patella (F–G). All measurements in millimeters.

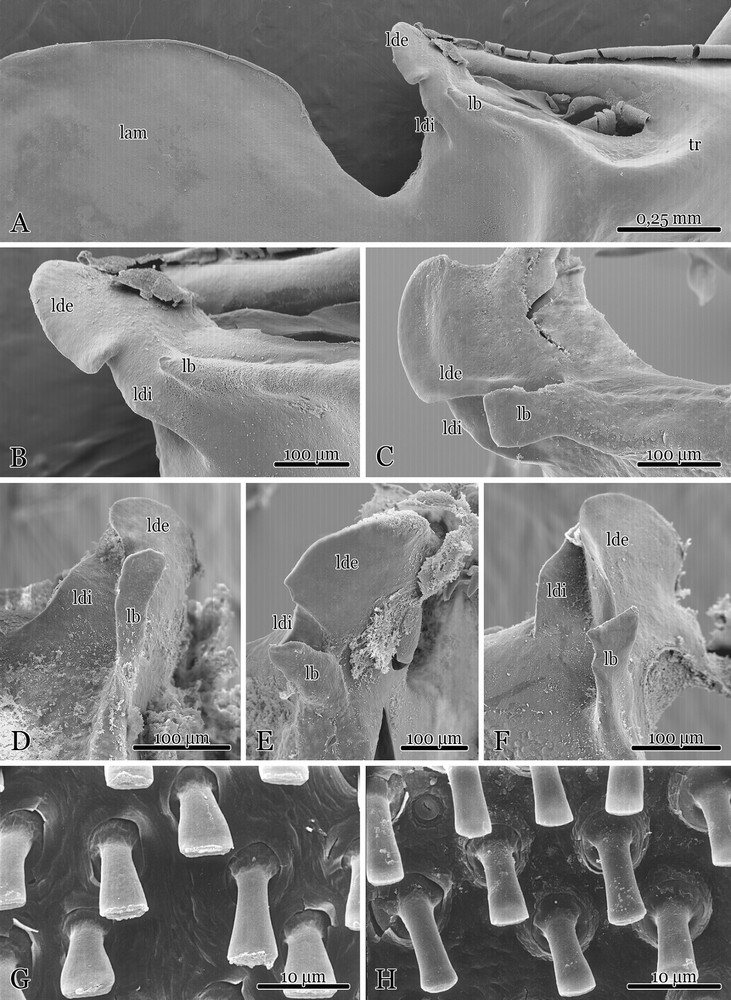

Hemispermatophore ectal view with part of the trunk and lamella, while the lobe region is entirely visible with the three lobes: the laterodistal lobe (ldi), the basal lobe (lb) and the outer distal lobe (lde) (A). Close up of the lobes in Euscorpius oglasae stat. nov. (B), E. carpathicus niciensis (C), E. tergestinus s.s. (D), E. balearicus (E), E. concinnus (F). Shape of peg sensilla of Euscorpius oglasae stat. nov.: male (G), female (H).

Trichobothrial counts and pectinal tooth count () of all analyzed specimens of E. oglasae Di Caporiacco, 1950, stat. nov.

| Code | m/f | ||||||||||||||||||||

| L | R | L | R | et | est | em | esb | eb | L | R | L | R | |||||||||

| L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | L | R | ||||||||||

| Eog564 | f | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog565 | m | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 29 | 29 |

| Eog566 | m | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog567 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog568 | f | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog569 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog570 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog571 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog572 | m | 6 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 22 | 23 | 31 | 30 |

| Eog573 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog574 | m | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog575 | m | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 22 | 23 | 29 | 30 |

| Eog576 | m | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 24 | 30 | 31 |

| Eog577 | m | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog578 | m | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog603 | m | 7 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 31 | 31 |

| Eog604 | m | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog605 | m | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog606 | m | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog607 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 22 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog608 | f | 6 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 31 | 30 |

| Eog609 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 24 | 30 | 31 |

| Eog610 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog611 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 22 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog218 | m | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog219 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog220 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog9728 | m | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog9729 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 21 | 30 | 28 |

| Eog9730 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog9731 | m | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 24 | 30 | 32 |

| Eog7396 | m | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog7397 | m | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog7398 | f | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 23 | 30 | 30 |

| Eog9973 | m | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 23 | 24 | 30 | 32 |

Euscorpius carpathicus oglasae Di Caporiacco [20 (p. 180)]; Valle [21 (p. 223); Bartolozzi et al. [22 (p. 297)]; Lacroix [26 (p. 19)]; Fet and Sissom [23 (p. 365)]; Vignoli [27 (p. 18)]; Fet and Soleglad [24 (pp. 16, 18, 22, and Fig. 34)]; Fet et al. [25 (p. 52)]; Vignoli et al. [29 (pp. 104, 106, 109)]; Vignoli [28 (pp. 19, 40, 65, 67, 82)]; Salomone et al. [31]; Vignoli et al. [30].

Diagnosis. Large species (total length of largest analyzed specimens: male, 36.2 mm; female, 43.0 mm); overall body light in color with reddish pedipalp chela fingers and the V metasomal segment darker. It is an oligotrichous form with series and . It can be distinguished from the species belonging to the ‘tergestinus’ complex by the following characters: the inner proximal surface of pedipalp movable finger with reduced lobe in male and obsolete in female; the telson vesicle in males is slightly swollen; the lateral eyes are similar in dimensions; the hemispermatophore is relatively small with the basal lobe bearing a short spine at the posterior extremity (sensu Jacob et al. [37]). Additional peculiar characters are: the dorsal patellar spur (DPS) is short and the pectinal tooth count is low: 7/7 (males), 6/6 (females). It appears to be more closely related to E. balearicus than to the other species belonging to the ‘tergestinus’ complex.

Material examined. A total of 35 specimens were analyzed. MCSNB: 2 males (9728, 9731), 2 females (9729, 9730), no exact locality, V.1973, Fanfani coll.; 2 imm. males (7397–7398), 1 male (7396), no exact locality, 03.V.1967, Bruno S. coll.; 1 imm. male (9973), no exact locality, 07.X.1974, Brignoli coll. VVZC: 2 imm. males (Eog218–219), 1 juv. female (Eog220), no exact locality, 13.07.1968, Lazzeroni L. coll.; 2 juv. females (Eog605–606), Loc. Collo dei Lecci, about 400 m a.s.l., N 42°, E 10°; 4 females (Eog607–610), 1 imm. female (Eog611), 28.X.2005; 9 females (Eog564–572, 578), 4 males (Eog573–576), 1 imm. female (Eog577), N 42°, E 10°, Loc. Cala Maestra, 12 m a.s.l., 14.X.2005, Vignoli V. & Cicconardi F. coll.

Description of selected topotypes: male (Eog575) and female (Eog607).

Color. Mesosomial tergites olive green-brown, carapace similar but slightly more reddish, metasoma similar as mesosoma with V segment darker. Vesicle yellow with reddish aculeus (Fig. 3A and B). All leg segments yellow in color; chelicera yellow with apical portion slightly darker; pedipalp femur, patella and chela yellow with the latter two segments slightly darker, fingers are reddish. Sternites olive green; coxal regions reddish and sternite, pectens and genital operculae yellowish. Pleural membrane dark brown. Chelicera yellow without pattern.

Carapace. Carapace length: 5.5 mm (male), 6.1 mm (female). Smooth with few granules on lateral regions in females; slightly granular on anterior and central regions, while stronger granulation is present on the lateral portions in male. Posterior and postero-lateral furrows deep. Lateral ocelli very similar in size.

Mesosoma. All tergites acarinate, smooth in female and very slightly granular in the male. Distal lateral portion of tergite VII showing few granulations. Sternites smooth; stigmata small, oval in shape.

Metasoma. Generally short in size with respect to body length. First segment with only dorsal and dorsolateral carinae present, partially granular; all intercarinal surfaces smooth in females, while in males the dorsal portions are sparsely granular. Segment II–IV: dorsal carinae partially granular; dorsolateral and ventrolateral carinae smooth; intercarinal surfaces smooth. Segment V: both sexes with similar granulation; ventromedian and ventrolateral carinae granular; ventral intercarinal surfaces sparsely granular with smaller granules. Dorsolateral carinae sparsely granular. Anal arch with several small tubercles. Males and females are quite similar in the granulation of metasomal segments.

Telson. Vesicle: smooth, with 10 long ventral setae; slightly swollen in male with vesicle length ca. twice longer than vesicle depth ( = 2.0–2.1); narrower in female (Fig. 3A); aculeus strongly curved (Fig. 3B).

Pectines, and peg sensilla shape. Pectines: tooth counts 6/6 in female, 7/7 in male; middle lamellae: 5/5; peg sensilla with typical shape (Fig. 4G–H) of the subgenus Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 as shown by Bonacina [39] and Vignoli et al. [29]. Pecten length: 3.0 mm. Several microsetae are present on all parts of pectens.

Genital operculum. Completely divided. Genital papillae externally visible in males. Six reddish macrosetae and several smaller setae are present.

Sternum. Pentagonal shape, type 2. Length similar as width (length: 1.7; width: 1.6) and posterior emargination deep.

Chelicerae. Dorsal surface of manus smooth with few reddish macrosetae. Ventral edge of movable and fixed finger as manus with brush-like setae on the entire surface.

Pedipalps. Stocky in general structure. Coxa with sparse granules, very strong granulation in males, few setae. Femur: male, 33% longer than wide; 35% in female. All carinae granular with dark spiny granules and intercarinal spaces with sparse dark granules, granulation stronger in males; few short transparent setae are present on all surfaces, but fewer on ventral and dorsal surfaces. Patella (Fig. 3F–G): male 35% longer than wide, female 40%. Dorsointernal carinae crenulate, dorsoexternal and ventroexternal carinae rough. Ventrointernal carinae weakly granulate. Dorsal intercarinal surface weakly granular in females, stronger in males; external intercarinal surface with sparse granules similar in both sexes. Ventral intercarinal surface smooth and with few small granules on the inner portion in males. Dorsal patellar spur short (0.35–0.37 mm), spiny (Fig. 3F) and with small granules at the base. Internobasal surface of pedipalp movable finger with reduced lobe in both male and female. Female with narrower pedipalp chela manus and inner surface of fixed finger straight. Chela (Fig. 3C, D). Dorsal carinae D1, D4, external and V1 are distinct with stout tubercles; carinae V2 more distinct in males than in females and composed by several small granules. All intercarinal surfaces are stronger granulated in males.

Trichobothria. Type C neobothriotaxic [33]. Patella (Fig. 3E–G). with typical trichobothria statistical ranges of the subgenus Euscorpius [40] () (Fig. 3F; Table 1). Patella external () formula (Fig. 3E): , , , , , ; is petite. Series em with trichobothria 1–2 and 3–4 forming a wide ‘V’ (Fig. 3E). Patella ventral (): 7/7. Chela trichobothria series V standard ().

Legs. All legs with two pedal spurs and lacking spines. Tarsus with ventromedian row (12–14) stout spinules; tarsal setae (adjacent to the median ventral spinule row), flanking pairs: 2–3. Basitarsus: 6–10 small ventral spinules on legs I–II, 4–6; on legs III–IV, 3 flanking setae.

Hemispermatophore. Broad trunk with deep truncal flexure, total length 5.1 mm. Capsular lobe with lde large and with slightly acuminate borders, central edge slightly convex; lb with very short spine in posterior direction (Fig. 4A–B), at least half as wide/long as the lde; no large acuminate process. Inner distal lobe (ldi) homogeneous in shape. Crown-like structure showing about 4–8 short spines similar in size.

Variations. The diagnostic characters are reasonably constant in all examined specimens. Limited variability can be observed with regards to the globosity in the telson vesicle of males. Pectinal teeth in males: 7/7 (61%), 6/6 (28%), (5%); females: 6/6 (82%), 6/7 (12%), 7/7 (6%) (Table 1). The pedipalp patella trichobothria has few variability, the series em, esb and eb are constant, while very low variability was observed for (11%), (3%); the series for only 14% of specimens (Table 1).

4 Discussion

Comparative morphology. The following comparative analysis is based on the observation of 337 specimens belonging to seven related taxa.

The presence of 5 trichobothria in the series et () is a particular character for the subgenus Euscorpius, but not unique to the Montecristo morphotype. Euscorpius carpathicus s.s. from Romania has prevalently , but specimens with are known in some cases [24]; nevertheless, this species is easily distinguished based on the presence of the series , instead of the typical of the entire ‘tergestinus’ group. Morphotypes with and are known from Greece and Bulgaria [41,42]. The presence of seems also to be present in the ‘E. sicanus’ complex with typical ; in Italy, the following taxa can occasionally show this pattern: E. c. calabriae Di Caporiacco, 1950, E. c. palmarolae Di Caporiacco, 1950 and E. c. sicanus Di Caporiacco, 1950 [43,44]. The same trichobothrial character was also observed in Greek populations belonging to the ‘E. sicanus’ complex: Essimi (Thrace), Samos Island (north Aegean) and Drama (Macedonia) [28].

Among the taxa belonging to the ‘E. tergestinus’ complex, and characterized by according to Fet and Soleglad [24], E. oglasae shows several morphological features that distinguish it from others. A comparative analysis was done with the taxa of the ‘tergestinus’ complex, which are geographically close to Montecristo Island (E. concinnus; E. tergestinus s.s.; E. c. corsicanus), while E. balearicus and the subspecies from southern France (E. c. niciensis) were also compared considering the paleogeography of the central and western Mediterranean region.

Morphometrics of the telson vesicle indicate that males have vesicle depth longer than half vesicle length, in E. c. niciensis (), E. concinnus and E. tergestinus s.s. (). In E. c. corsicanus, the telson is slightly less swollen (), while in E. balearicus the globosity of the vesicle is similar to that of E. oglasae ().

The presence of a lobe on the inner proximal surface of pedipalp movable finger is a common character for the genus Euscorpius and represents a secondary sexual dimorphic character, which is more pronounced in the males than in females. In E. oglasae, this lobe is less strong, especially in females than in all the other compared taxa (E. tergestinus s.s., E. concinnus, E. c. corsicanus, E. c. niciensis, E. c. apuanus) except for E. balearicus, which has similar weak lobes.

Another interesting character is the general dimension of the hemispermatophore, which is relatively small in E. oglasae if compared with the general size of the mature male. In most of the compared species the length of the hemispermatophore is longer than the carapace: E. concinnus (), E. tergestinus s.s., E. c. niciensis (). In E. c. corsicanus, the differences between carapace and hemispermatophore are less (), while this ratio is similar, as in E. oglasae and E. balearicus ().

The study of 70 hemispermatophores of five related taxa (E. tergestinus s.s., E. concinnus, E. c. corsicanus E. c. niciensis, E. balearicus) found some variability in shape and dimensions of the lobes, especially in the basal lobes (lb) (Fig. 4C–F); nevertheless, all of the analyzed lb of E. oglasae (10 hemispermatophores) seem to be quite similar, with a very short spine in posterior direction. Variability in this character for the genus, especially relating to the shape of the lobes, was studied by Jacob et al. [37], but the dimension of this spine could be considered as a diagnostic character, since this was well developed in all the other observed taxa.

The so-called ‘acuminate process’ of the hemispermatophore was considered a diagnostic character for E. tergestinus and synonymized taxa by Fet and Soleglad [24] including E. oglasae, but we did not observe this spine in any of our specimens.

Although the shape of the peg sensilla can be diagnostic at higher taxonomic ranks [21], the peg sensilla of both male and female were studied. The scanning microscopy images were compared with E. tergestinus s.s. and E. concinnus, but no differences were detected in general shape and E. oglasae bears the typical ‘clave’ structure with stumped extremity (Fig. 4G–H).

More morphological differences were observed during the comparative analysis and are reported below.

Euscorpius concinnus inhabits Tuscany mainland beside Elba and Palmaiola Island [29]. This species is polytrichous with respect to E. oglasae and shows and ; it is darker in color and smaller in general dimensions. A similarity among these two taxa is the ratio DPS/pedipalp patella length; this biometric value was fundamental to distinguish E. concinnus from E. tergestinus s.s. [29], while is not useful to separate E. oglasae from E. concinnus.

Euscorpius tergestinus s.s. is the largest Italian species belonging to the ‘tergestinus’ complex; the exact distribution is still to be determined, nevertheless this taxon seems to have a broad distribution through mainland Italy [29]. It differs from E. oglasae by several characters: a higher pectinal tooth count (); larger DPS; stronger granulation on lateral surfaces of femur of legs. Regarding the trichobothrial number and pattern, E. tergestinus s.s. differs by the following features: series em () with the angle between trichobothria 1–3 narrower; trichobothria et and est on fixed pedipalp finger more distant. We consider E. c. picenus Di Caporiacco, 1950 (, ) synonymous of E. tergestinus [24,29].

In the endemic subspecific taxon described from Corsica (France), E. c. corsicanus, the presence of higher trichobothrial counts (diagnostic for this taxon), in particular the patella ventral series of 10 trichobothria (, ) are consistent morphological evidences that separate this subspecies from other related taxa including E. oglasae [24]. Other characters typical of E. c. corsicanus are: smaller general dimensions and lighter in color with pedipalps intercarinal surfaces yellow and carinae dark reddish; chelicera with reticulated pattern more or less accentuated. The dorsal and ventral carinations, in both sexes, are similar to those in E. oglasae, except: segment I, where the dorsolateral carinae is obsolete, while weak in E. oglasae; V segment in E. oglasae, with slightly larger granules. Telson in males with a strong curved aculeus. Granulation of prosoma and leg femur weak with respect to E. oglasae (in both sexes).

Euscorpius c. niciensis, which has a distribution in southern France and Liguria (northwestern Italy), is smaller in size with respect to E. oglasae, with marbled infuscation on the chelicerae. Differences were observed in metasomal carination. Dorsal metasomal carination of the I segment slightly stronger in E. oglasae, while dorsal carinae of the other segments are quite similar; inner dorsal surfaces are more rough in E. c. niciensis (in both sexes). Ventral metasomal carination is similar, except the V segment, which is stronger, more granulated than in E. oglasae (in both sexes). Another noteworthy difference in E. c. niciensis is the structure of the pedipalp chela, which has short fingers and pedipalp chela carination and granulation similar, while stronger on pedipalp patella and femur in E. c. niciensis (in both sexes). Leg femur granulation is similar in males, while quite stronger in females of E. oglasae. Carapace granulation of E. c. niciensis is more homogenous, with small granules.

Euscorpius c. apuanus is a large peculiar (, ) subspecies, endemic of the Apuan Alps in central Italy, at present considered as synonymous of E. tergestinus [24]. This taxon is more polytrichous, with a less carinate metasoma with respect to E. oglasae.

Concerning the endemic species of the Balearic Islands (Spain), E. balearicus, the detailed morphological study of Gantenbein et al. [45] gives evidence of a highly divergent lineage separate from all the other euscorpiids. The polytrichy of this taxon is significant (series , with and ) and also the morphometric ratios are peculiar, e.g., the short metasoma and large pedipalp chela. If compared with E. oglasae, E. balearicus is smaller in general size with a larger DPS and chelicera without maculation. Additional distinguishing characters of E. balearicus are the following: metasomal and pedipalp carination and granulation evidently more weak, except: inner surface of pedipalp femur with smaller and less spines; I metasomal segment with obsolete dorsolateral carinae (in both sexes); telson shape in both sexes similar, while the aculeus is more curved in males; DPS larger and spiny; pedipalp chela more slender in both sexes.

Specimens of E. c. fanzagoi (Simon, 1879), described from the Pyrenees, were not available for this study and its enigmatic taxonomical validity [25] remains unclear.

Ecology. Euscorpius oglasae, as the other species of Euscorpius, is a hygrophilous species and was found only in humid areas, around the only house present on the island, at Cala Maestra, and in a non-anthropic area at Collo dei Lecci. This scorpion does not seem to be either a specific corticicolous or a lapidicolous species, as it was collected in both microhabitats. In Cala Maestra, the specimens were found under bark of Pinus and Eucaliptus, but also under stones of small walls. At Collo dei Lecci, only two specimens were collected, one under a small stone, the second inside a rotten log of Erica (saprossilic microhabitat). The climate of Montecristo is temperate-warm and this probably constitutes a factor of stress for this species during the summer and the early autumn. Therefore, this taxon might be limited to few areas of the island, since granite flat rocks cover most of the area with high exposition to the sun (Fig. 2B–D). We presume that E. oglasae is restricted on the island only to well-vegetated and shady areas, close to streams and caves or in rocky crevices into shady cliffs.

Conservation. The importance of the conservation of the scorpion species in Europe was taken into consideration for the first time by Sochurek [46], for the Austrian euscorpiids; at present, the only country where autochthonous species are included in the ‘red list’ is Austria [47,48]. In Italy, the only observations related to scorpion (E. italicus (Herbst, 1800)) conservation were published by Crucitti [49], while the conservation status was also raised for scorpion species living in Switzerland by Braunwalder [50]. We also want to stress the importance of protecting euscorpiids in Italy. Attention should be given to several localized taxa, both on islands and mainland, e.g., E. c. apuanus from the Apuan Alps (Italy). Continental and insular endemisms constitute unique genetic pools regardless of their taxonomic status as subspecies or species. It is also known that invertebrates with restrict distribution, as short-range and insular endemisms, can be very vulnerable and therefore play a significant role in conservation planning [51–53]. The risk of extinction of E. oglasae is presumably high, since it is distributed on a very small area, where, in addition, the peculiar climate and vegetation force the population to concentrate in a few year-long humid microhabitats. Moreover, the shady autochthonous oak forests are endangered by the high presence of wild goats, which prevent new plants from growing up and replacing dead trees. Loss of habitats and risk of turnover events by passive anthropogenic introgression of larger xerotherm congeneric species (e.g., E. italicus and E. flavicaudis (De Geer, 1778)) as alien species could lead to the extinction of this taxon.

5 Conclusions

We present several morphological features that indicate significant separation of this taxon from all other known taxa and morphotypes: trichobothrial pattern ; ; the low pectinal tooth count (); inner proximal surface of pedipalp movable finger with reduced lobe; telson vesicle in males slightly swollen; dorsal patellar spur short; hemispermatophore basal lobe with a very short spine at the posterior extremity. On the basis of the data presented here, we are confident that this is a valid species and elevate the subspecies to species rank accordingly. Additional support for our conclusions is provided by preliminary molecular evidences [31].

Our morphological analysis clearly indicates E. oglasae as a well-distinguishable form; nevertheless, some similarities were observed. E. tergestinus s.s. is similar in general biometric aspect (pedipalp chela length/width, metasoma V segment length/width), in shape of peg sensilla and partially in trichobothria pattern (occasionally ()). The most similar taxon seems to be E. balearicus for the shape of the telson vesicle in males, the weak lobe on the inner proximal surface of pedipalp movable finger and the dimension of the hemispermatophore.

The high exomorphological differentiation of E. oglasae is probably the result of the peculiar geological history of the Montecristo Island. Since this island is surrounded by the bathymetric line of 200 m [54], the Pleistocene (18 000 yr ago) glacio-eustatic event, due to glaciations, is unlikely to have created effective land bridges with the mainland and neighboring islands in contrast to the other islands of the same Archipelago [1,43,55]. This suggests a long isolation from neighboring populations, and therefore E. oglasae is likely to represent a paleo-endemic species of the central Mediterranean area.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the people who provide specimens: S. Whitman (MZUF), M. Valle (MCSNB), P. Crucitti (Società Romana di Scienze Naturali, Roma, Italy), A. Petrioli, M. Bastianini, J. Ove Rein, D. Facheris and M. Colombo. Thanks to G. Dupré (Paris, France) for providing bibliography. We would particularly like to thank the Corpo Forestale, Dr. Vaniluca and Isp. Sup. Fabiani of UTB Follonica (GR) for the collecting permits for Montecristo Island. V.V. and F.C. are grateful to the wildlife guards for their kind effort during the expedition and the Benelli family for the hospitality on the island. The visit of V.V. to the MNHN was financially supported by SYNTHESYS (European Union-Funded Integrated Infrastructure Initiative grant). The first author is grateful to C. Rollard, W. Lourenço, C. Hervé, and E. Leguin (MNHN, Paris) for their generous assistance. The collecting trips to Montecristo Island of V.V. and F.C. were financed by University of Siena and the MIUR. We also thank the following people from the American Museum of Natural History (New York, USA): E.S. Volschenk and L. Esposito, for useful comments and improving the language of the manuscript, and L. Monod for translating the abstract.