1. Introduction

Eukaryotic protein synthesis is slower than in prokaryotic systems, but displays greater regulatory complexity, allowing precise control of gene expression and protein production. Although basic mechanisms of translation elongation and peptide bond formation are conserved between bacteria and eukaryotes, several features of translation elongation are unique to eukaryotes.

The coordinated movement of mRNA and tRNAs through the ribosome—known as translocation—is essential to advance the translational reading frame of mRNA by one codon (nucleotide triplet) at a time. In prokaryotes, elongation factor G (EF-G) and, in eukaryotes, elongation factor 2 (eEF2) catalyzes this process during protein synthesis. During translocation, the ribosome can switch to an alternative reading frame (frameshift) resulting in an altered amino acid sequence downstream of the frameshift site. Moreover, if the new frame contains a premature stop codon, the translation process would terminate early, resulting in a truncated protein. While frameshift events in bacteria can be beneficial—making efficient use of limited genomic material—translational frameshifts in eukaryotes can lead to non-functional, aberrant proteins that could compromise cell homeostasis and viability. Besides, many viruses employ programmed ribosomal frameshift mechanisms to regulate the expression of overlapping gene sequences. For instance, viruses such as HIV or Sars-Cov-2 leverage −1 programmed ribosomal frameshifts in host cells to produce functionally distinct proteins from overlapping reading frames. Interruption in the reading frame, or frameshifting, can be disastrous for cells and, in general, can be caused either by direct mutations in eEF2, impairment in the synthesis of specific modifications of eEF2, or imbalance in the protein synthesis apparatus. Spontaneous ribosomal frameshifting leads to a wide spectrum of diseases, including human neurodegenerative disorders such as spinocerebellar ataxias, spinobulbar muscular atrophy, Huntington’s and Alzheimer’s diseases.

While a number of structural studies have analyzed bacterial translocation intermediates using X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM (Carbone et al., 2021, Petrychenko et al., 2021, Ramrath et al., 2013, Rundlet et al., 2021, Zhou et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2014)—while focusing on EF-G as a model for GTPase-driven translocation—our understanding of eukaryotic ribosomal translocation, and more importantly, the integrity of codon–anticodon interactions, has been limited by the challenges of achieving high-resolution structures (Djumagulov et al., 2021, Flis et al., 2018, Taylor et al., 2007). In contrast to its prokaryotic counterpart, the eukaryotic 80S ribosome relies on unique post-transcriptional modifications of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and tRNAs, as well as kingdom-specific elongation factors, which contribute to enhanced translation accuracy. The higher complexity of eukaryotic translocation is also reflected by additional regulatory mechanisms, such as phosphorylation of elongation factor 2 (eEF2), which results in reduced rates of protein synthesis (Carlberg et al., 1990). eEF2 is a eukaryotic GTPase that drives translocation, and—along with archaeal aEF2—contains a highly conserved post-translational hypermodification known as diphthamide, which is absent in prokaryotes. Diphthamide is targeted by at least two virulent toxins—diphtheria toxin and Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A—which transfer ADP ribose to the modification and inactivate eEF2 leading to cell death (Jorgensen et al., 2006). Diphthamide biosynthesis is carried out by a set of highly conserved proteins; yeast strains lacking these enzymes display increased mRNA frameshifting, pointing to the crucial role of the modification in protein synthesis fidelity (Ortiz et al., 2006). The absence of diphthamide is associated with increased sensitivity to oxidative stress, neurodegenerative diseases, and heightened susceptibility to apoptosis. A recent crystal structure of a ribosome translocation intermediate from Saccharomyces cerevisiae highlighted the role of diphthamide in stabilizing the codon–anticodon duplex during early translocation (Djumagulov et al., 2021), yet its function in other phases remained unclear.

In this study, we presented ten high-resolution cryo-EM structures (up to 1.97 Å) of the elongating 80S Saccharomyces cerevisiae ribosome in complex with the full translocation module, including mRNA, peptidyl-tRNA, and deacylated tRNA (Milicevic et al., 2024). Seven of these structures also featured ribosome-bound naturally modified eEF2 (ibid.). Early translocation intermediates demonstrated how eEF2 is recruited on spontaneously rotated ribosomal conformations and facilitates the translocation of peptidyl-tRNA once fully accommodated on the 80S ribosome (ibid.). Our findings elucidated the molecular mechanisms that maintain the eukaryotic translational reading frame, showing how specific elements of the 80S ribosome, eEF2, and tRNAs undergo significant rearrangements to preserve mRNA reading frame integrity throughout the translocation process (ibid.).

2. High-resolution cryo-EM reconstructions of the elongating eukaryotic 80S ribosome

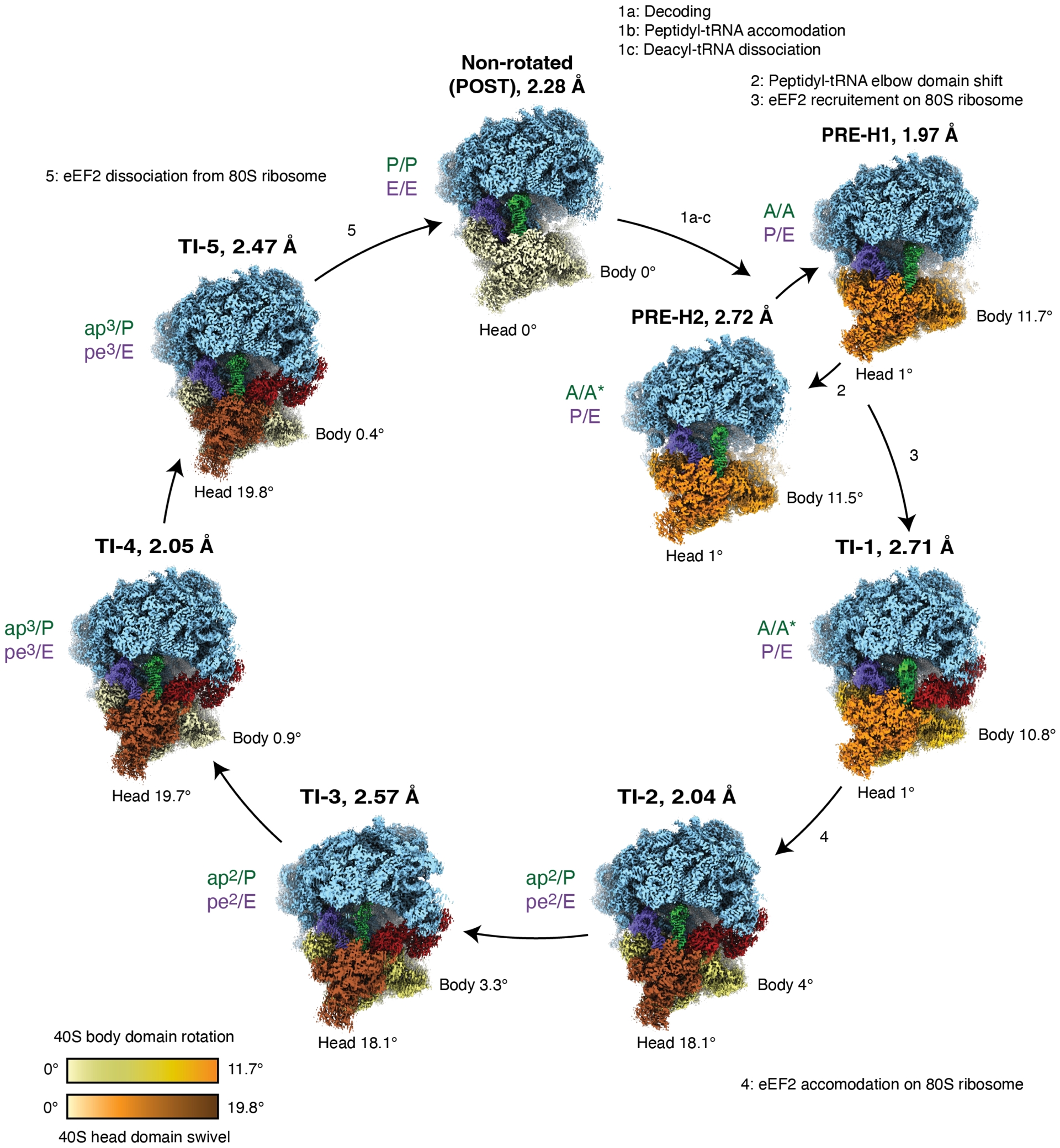

We conducted an in vitro peptidyl-transferase reaction and ribosomal complex formation using Saccharomyces cerevisiae ribosome, aminoacylated tRNAs and endogenous eEF2. Then, using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), we captured a set of distinct high-resolution ribosomal conformational states, including seven with bound eEF2 (Milicevic et al., 2024). These structures revealed various large-scale conformational changes, eEF2 recruitment and accommodation events, as well as tRNA and mRNA movements (ibid.), illustrating the dynamics of the ribosomal translocation process (Figure 1).

High-resolution cryogenic-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) reconstructions and reported resolutions of the translocating eukaryotic 80S ribosome during the elongation step of protein synthesis. Following decoding and peptidyl-tRNA accommodation, small 40S subunit body domain (light yellow to orange) undergoes forward rotation relative to the large 60S subunit (light blue) and forms a PRE-translocation-hybrid (PRE-H) state. Peptidyl-tRNA (green) elbow domain shift, as observed from PRE-H1 to PRE-H2, permits eEF2 (red) recruitment on 80S and formation of an early translocation intermediate (TI-1). As the translocation reaction progresses and enters its late phases (TI-2 to TI-5), 40S body domain undergoes backward rotation, while 40S head domain performs forward swiveling motion (light yellow to brown), coinciding with peptidyl- and deacyl-tRNAs (violet) advancement. Final tRNA translocation positions are observed in the classical, non-rotated, state. Angle values refer to 40S body domain rotation relative to the large 60S subunit, and 40S head domain rotation with regard to 40S body domain. tRNA states on the ribosome are defined according to positions of acceptor and anticodon stem loops relative to ribosomal A (acceptor), P (peptidyl) and E (exit) sites on large and small subunits, respectively. Atomic models and cryo-EM maps are available through PDB and EMDB with the following identifiers: PRE-H1 (8CCS, EMD-16563), PRE-H2 (8CDL, EMD-16591), TI-1 (8CF5, EMD-16616), TI-2 (8CDR, EMD-16594), TI-3 (8CG8, EMD-16634), TI-4 (8CEH, EMD-16609), TI-5 (8CIV, EMD-16684) and NR (8CGN, EMD-16648). Two additional structures, TI-1∗ (PDB: 8CKU, EMD-16702) and TI-4∗ (PDB: 8CMJ, EMD-16729) are not shown.

In early translocation states (PRE-H1 and PRE-H2; PDB IDs 8CCS, 8CDL, respectively), small 40S subunit underwent pronounced rotation of approximately 12° relative to the large 60S subunit. We also described a highly pronounced shift of the elbow domain of peptidyl-tRNA (A/A to A/A∗), necessary for eEF2 recruitment (TI-1; PDB ID 8CF5). Five key translocation intermediates (TI-1 to TI-5; PDB IDs 8CF5, 8CDR, 8CG8, 8CEH and 8CIV, respectively) were identified, with TI-1 representing the earliest, and TI-5 the latest stage of eEF2-assisted translocation. During this transition, small 40S subunit body domain rotates backwards toward the classical, non-rotated state (PDB ID 8CGN), while its head domain rotates forward, coinciding with tRNA advancement.

Since one of the highly advanced states, TI-3, was resolved with eEF2 bound to a non-hydrolyzable analog of GTP, GMPPCP, our data suggest that GTP hydrolysis is not necessary for tRNA advancement per se; rather, the role of eEF2 is to uncouple mRNA-tRNA advancement from thermally driven backward rotation of the small subunit body domain.

3. Recruitment of eEF2 on the 80S ribosome and translocation of the mRNA–tRNA2 module

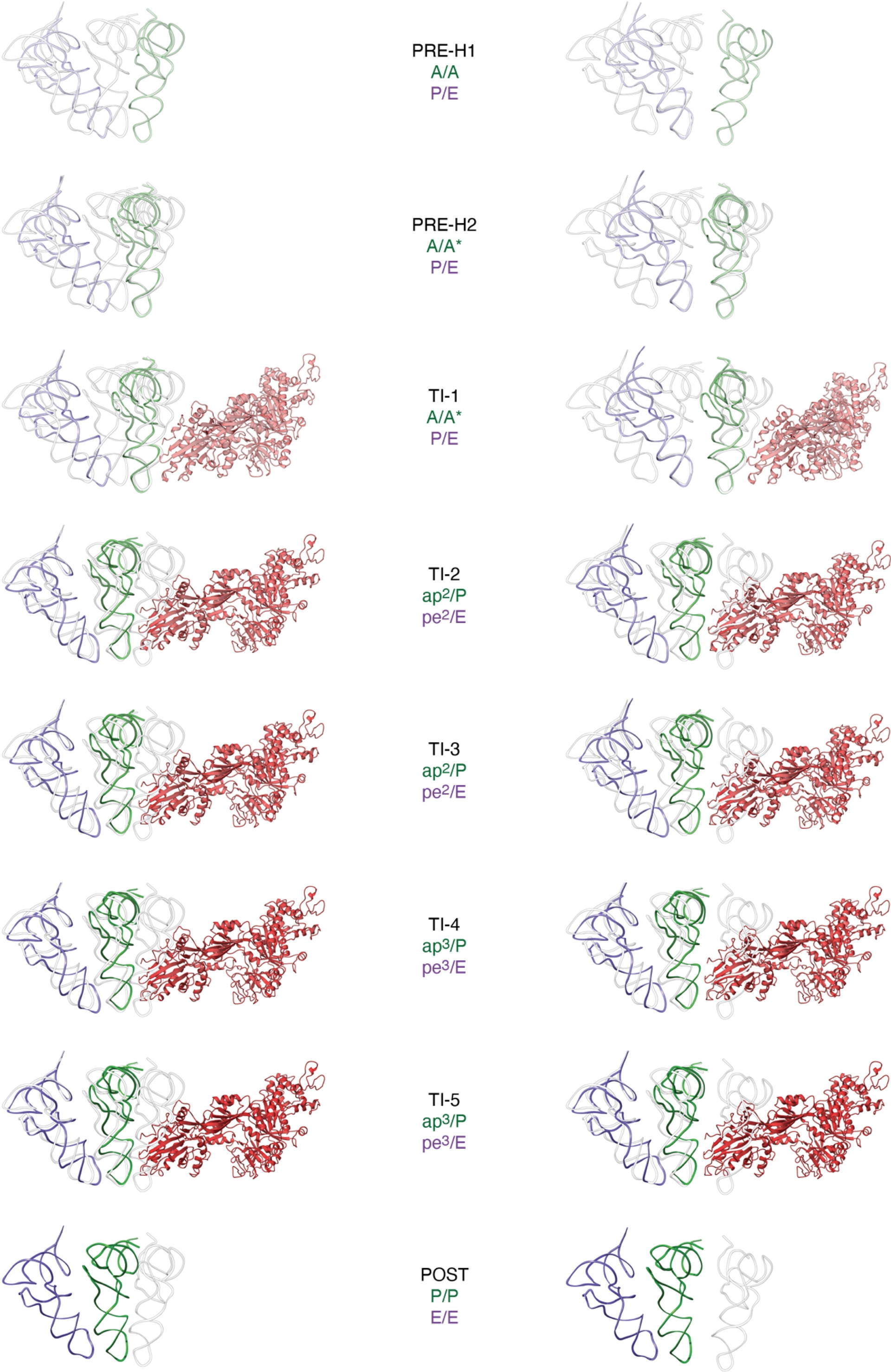

Our data showed that eEF2 engages fully rotated PRE-H2, in which the tRNAs have already largely advanced relative to their initial, classical, states (ibid., Figure 2). Indeed, deacyl tRNA is seen spontaneously translocating from P/P to the hybrid P/E state, while the elbow domain of peptidyl-tRNA rotates in the forward direction and occupies the A/A∗ state. The fact that tRNA configuration does not change upon eEF2 recruitment (PRE-H2 vs. TI-1) is in favor of the observation that PRE-H2 can already be considered a translocation intermediate as such, and, that one of the intrinsic properties of the ribosome is to spontaneously translocate tRNAs (ibid.).

Overall advancement of tRNAs during eukaryotic ribosome translocation. For each translocation complex, positions of peptidyl-tRNA (shades of green), deacyl-tRNA (shades of violet) and elongation factor 2 (shades of red) are depicted relative to classical positions of tRNA (A/A, P/P and E/E, shown in grey). On the left, alignment on large subunit ribosomal RNA (25S) and, on the right, alignment on the body domain of the small subunit ribosomal RNA 18S. Atomic models are available through PDB: PRE-H1 (8CCS), PRE-H2 (8CDL), TI-1 (8CF5), TI-2 (8CDR), TI-3 (8CG8), TI-4 (8CEH), TI-5 (8CIV) and POST (8CGN).

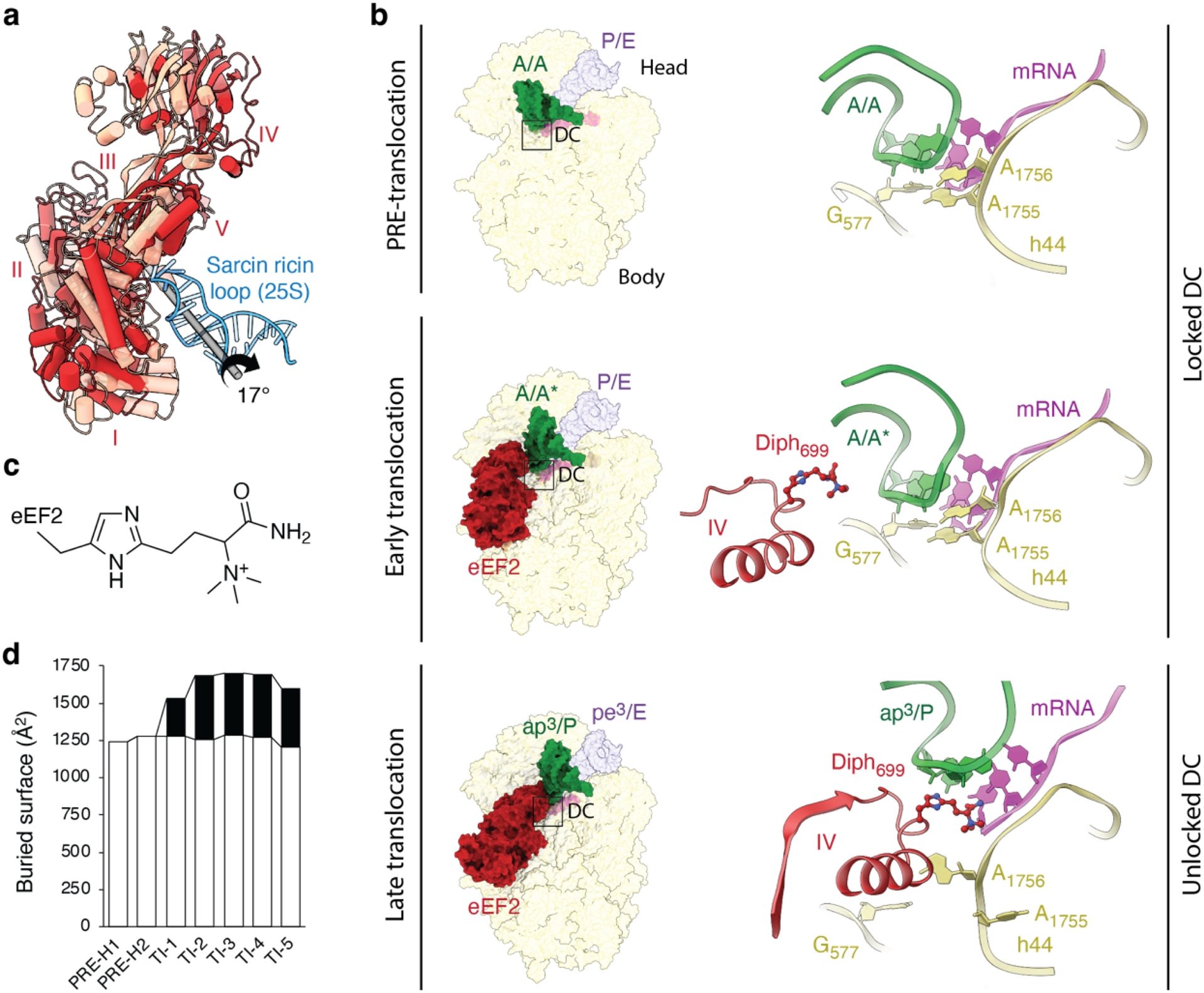

Furthermore, in the TI-1 state, eEF2 is seen interacting with the 80S ribosome, with domains I and V binding to the conserved sarcin–ricin loop (SRL) of 25S rRNA (ibid.). As TI-1 progresses to TI-2, eEF2 rotates approximately 17° around the SRL (Figure 3a), adopting its fully accommodated position on the 80S ribosome (ibid.). During this transition, the decoding center unlocks, allowing eEF2’s domain IV to move about 19 Å into the A-site, where it interacts directly with the minor groove of the codon–anticodon duplex formed by peptidyl-tRNA and the A-codon (Figure 3b,c). Full accommodation of eEF2 is accompanied by further backward rotation of the SSU, indicating that the unlocking of the decoding center is a key step during the transition from TI-1 to subsequent translocation states (ibid.).

(a) Rotation-like movement of eEF2 around the sarcin-ricin loop (SRL) on its transition from the engaged (TI-1, in pink) to the accommodated state (TI-2, in red) on the 80S ribosome. (b) Interface view of the small 40S subunit and its decoding center (DC) as it undergoes unlocking of decoding nucleotides (G577, A1755 and A1756), and protrusion of domain IV of eEF2 (red) into the A-site. On the left, overall view of small 40S subunit and relative positions of tRNAs (peptidyl-tRNA in green and deacyl-tRNA in light violet), and eEF2 in PRE-translocation (as in PRE-H1), early translocation (as in TI-1), and late translocation (as in TI-4). Black squares indicate the position of DC. On the right, zoom on DC, its conserved decoding nucleotides, the tip of domain IV and its diphthamide hypermodification. (c) Chemical structure of hypermodified diphthamide residue 699 (Diph) found in archaeal and eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2). (d) Contact area measurements corresponding to buried surface areas observed between the tRNA2-mRNA module and 80S ribosome (white), and eEF2 domain IV (black), respectively, and as calculated for each individual state from PRE-H1 to TI-5. Atomic models are available through PDB: PRE-H1 (8CCS), TI-1 (8CF5) and TI-4 (8CEH).

From TI-2 to TI-5, the ribosome undergoes significant conformational changes, with further reverse rotation of 40S body domain and forward swiveling of the head domain, positioning the mRNA–tRNA2 complex closer to its final translocation state (ibid.). Throughout this process, eEF2’s domain IV maintains its conformation and position on the small subunit, as well as the mRNA-tRNA2, with the exception of a minor advancement from TI-2/TI-3 to TI-4/TI-5 (ap2/P-pe2/E vs. ap3/P-pe3/E) (ibid., Figure 2). The structures obtained in the presence of the non-hydrolyzable GTP analog, GMPPCP, reveal that translocation can reach a late intermediate state even without GTP hydrolysis (ibid.). This suggests that eEF2’s primary role in translocation is to prevent reverse rotation of the small subunit head domain (ibid.). Once in its fully accommodated position on the 80S ribosome (as seen from TI-2 to TI-5), the contact area formed by domain IV of eEF2 and the mRNA-tRNA2 duplex remains relatively constant (Figure 3d). Altogether, these observations suggest that eEF2 effectively acts as a molecular “doorstop”, as initially proposed (Inoue-Yokosawa et al., 1974, Kaziro, 1978).

4. mRNA path on the eukaryotic 80S ribosome and maintenance of the translational reading frame during translocation

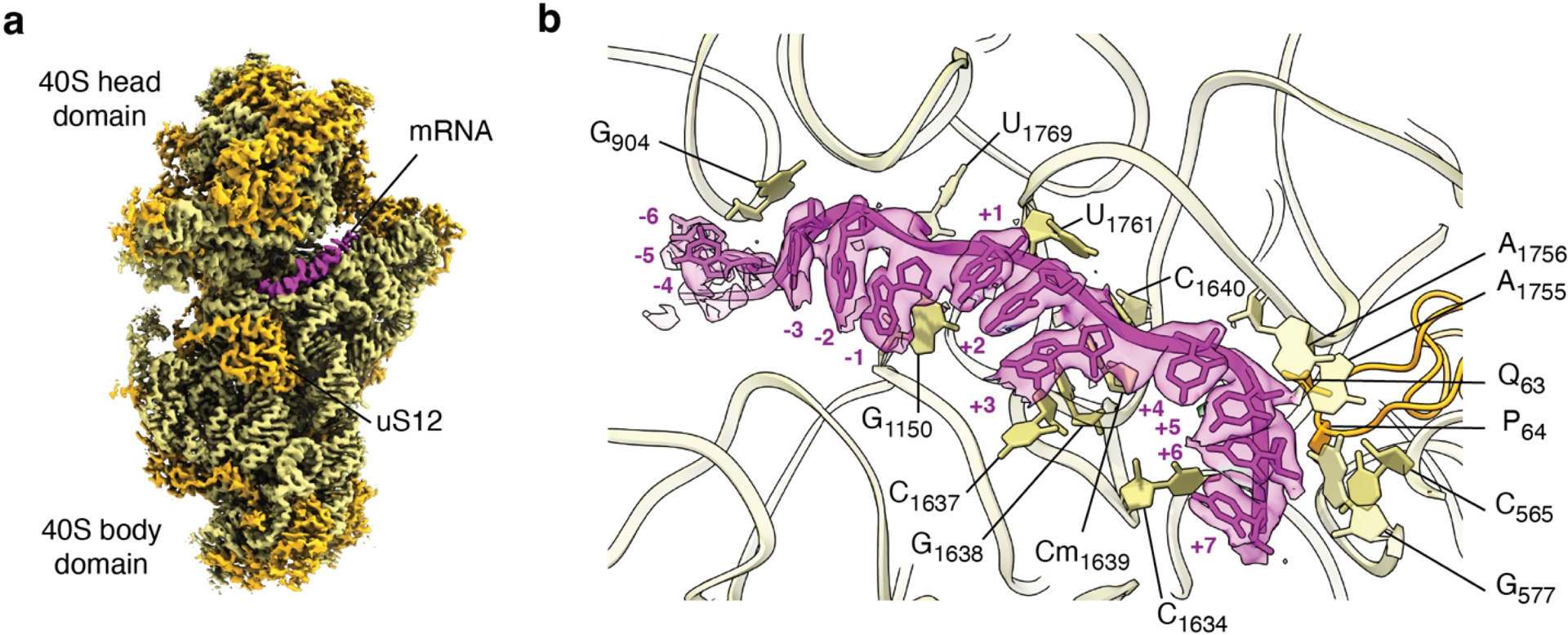

Early translocation intermediates (PRE-H1, PRE-H2 and TI-1) showed density for six mRNA nucleotides upstream of the P-site (Milicevic et al., 2024). Together with the six mRNA nucleotides found in A- and P-sites and one nucleotide downstream of the A-site, the newly characterized density has allowed to reconstruct a thirteen-nucleotide long path of mRNA through the rotated form of the eukaryotic 80S ribosome and describe the interacting counterparts of 18S rRNA and the conserved SSU protein uS12 (ibid., Figure 4a,b).

Path of messenger RNA on the eukaryotic ribosome. (a) Lateral view of the full 40S small subunit of the eukaryotic ribosome trapped in the PRE-hybrid 1 reconstruction (PRE-H1), revealing the messenger RNA path (magenta) at the head-body domain interface. Unsharpened, unfiltered high-resolution cryo-EM map is shown at 𝜎 = 3.5. 18S ribosomal RNA is colored in yellow, small subunit proteins are depicted in orange. (b) Zoom on the thirteen nucleotide-long messenger RNA and the interacting residues of 18S ribosomal RNA (yellow) and uS12 (orange). +1 indicates the first nucleotide of the start codon. mRNA density is contoured at 𝜎 = 3.5. The atomic model and the respective cryo-EM map of the PRE-H1 intermediate are available through PDB and EMDB with the following identifiers: 8CCS, EMD-16563.

In all three of the mentioned intermediates, the codon/anticodon duplex is found locked in the decoding center as a result of an intricate network of interactions equivalent to the one observed in prokaryotes (Demeshkina, 2012, Figures 3b, 4b and 5). An additional eukaryote-specific interaction of the second codon nucleotide, however, originates from its interaction with the eukaryote-specific glutamine residue 63 of uS12 (Milicevic et al., 2024).

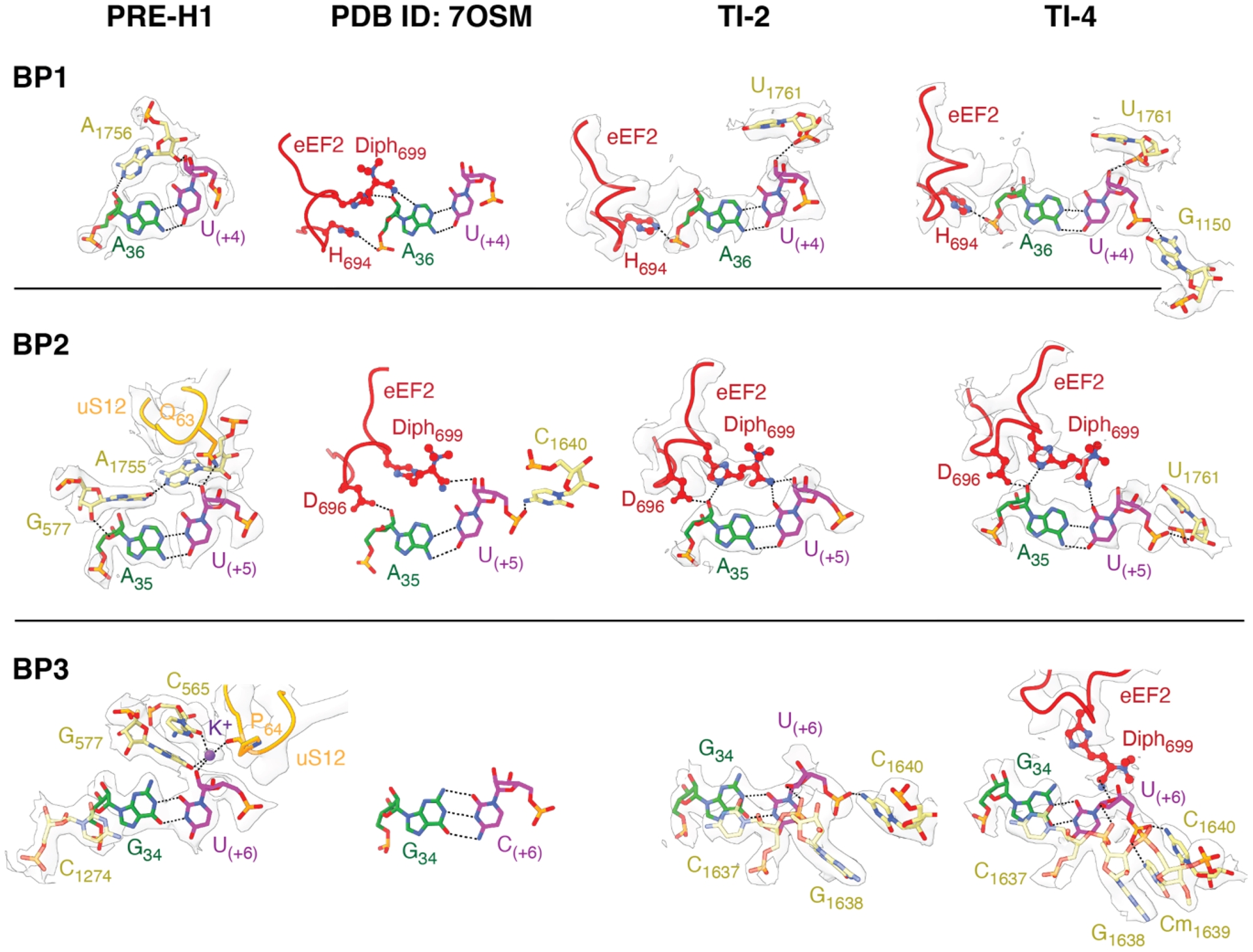

Interactions of codon–anticodon base pairs (BP) with residues of eEF2 domain IV (red), 18S rRNA (yellow) and the small 40S subunit protein uS12 (orange), as observed in PRE-H1, PDB ID 7OSM, TI-2 and TI-4 states. Conserved decoding nucleotides in PRE-H1 are found in the locked conformation. Diphthamide (Diph) interacts with the first base pair in PDB ID 7OSM, stabilizes the second codon–anticodon BP in PDB ID 7OSM, TI-2 and TI-4, and senses the third BP in TI-4. Top, middle and bottom panels correspond to first (BP1), second (BP2) and third (BP3) BPs, respectively. Cryo-EM density is contoured at 𝜎 = 3.5. Atomic models and cryo-EM maps are available through PDB and EMDB with the following identifiers: PRE-H1 (8CCS, EMD-16563), TI-2 (8CDR, EMD-16594) and TI-4 (8CEH, EMD-16609).

Upon eEF2 accommodation on 80S and formation of TI-2, domain IV of eEF2 protrudes into the A-site (Figure 3b) where its diphthamide hypermodification forms three hydrogen bond interactions through the minor groove of the second codon/anticodon base pair (ibid., Figure 5). Additional stabilization of the codon/anticodon pair in TI-2 is ensured by 18S body domain residues 1637, 1638, 1640 and 1761, which are further reinforced by residues 1150 and 1639 in later stages, i.e. TI-4 (ibid., Figure 5). Cryo-EM reconstructions of TI-3 and TI-4 also suggest that diphthamide undergoes small conformational remodeling which places it at the hydrogen bond distance from the ribose moiety of the third codon nucleotide with which it could interact by means of O-amide protonation (Milicevic et al., 2024). Overall, these observations suggest that diphthamide acts to maintain the translational reading frame by stabilizing the second codon/anticodon base pair throughout translocation, while transiently probing the third base pair (ibid.).

Ultimately, besides stabilizing the Watson–Crick pairing of the second codon/anticodon base pair, diphthamide and domain IV of eEF2 impose steric restraints on the second codon/anticodon base pair and prevent Wobble geometry at this position (ibid.).

5. Conclusion

Our recently published study provided atomic-level insights into the movement of the mRNA–tRNA2 module during eukaryotic protein synthesis (ibid.). We characterized translocation intermediates (TIs) of the eukaryotic 80S ribosome and reveal how eEF2 is recruited and accommodated on a spontaneously rotated 80S ribosome, while emphasizing the role of eukaryote-specific elements in maintaining the accuracy of translation by preventing the slippage of the mRNA reading frame (ibid.). Ultimately, we proposed that the eukaryote-specific diphthamide hypermodification enhances accuracy by stabilizing codon–anticodon interactions and sterically preventing Wobble geometry of the second base pair to enhance translation fidelity in eukaryotes (ibid.).

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Funding

This work was supported by La Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale grant no. DEQ20181039600 (to MY).

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0