1. Introduction

CRISPR homing gene drive belongs to a special category of technologies that can potentially have widespread impacts on natural populations and the environment. This makes it particularly difficult to fully anticipate and manage the associated risks, as for other high-impact technologies like nuclear physics, geo-engineering or the manipulation of viruses with pandemic potential. Despite this conundrum, the present context is highly conducive to the development of such high-impact technologies, for at least three reasons. First, as research advances, technologies are becoming more and more efficient and accessible, and thus likely to have larger effects. Second, competitiveness between teams and between countries, as well as the promotion of “High Risk, High Gain” research, via funding incentives and possibly facilitated access to top science journals such as Nature and Science, encourage the development of such research. Third, the climate change and the biodiversity crisis can lead some people to place excessive hopes in such technologies to address the current challenges and thus encourage further development of these approaches. For the particular case of gene drive, the major arguments put forward to promote the development of this technology relate to the fight against mosquito-borne infectious diseases: failure of current insect control methods to curb disease transmission and to stop the spread of arboviruses (especially dengue, with record numbers of infections in recent years), due in particular to the spread of insecticide resistance, the expanding range of vector mosquitoes, increasing pathogen resistance to medication and the absence of, or low accessibility to, efficient vaccines (Weng et al., 2024).

Undertaking a benefit-risk assessment of CRISPR homing gene drive is inherently difficult. It is impossible to fully anticipate all possible impacts. Furthermore, there is no standard method to weigh up the various pros and cons in a way that would satisfy everyone, according to their various perspectives. Nevertheless, in order to decide whether CRISPR homing gene drive should be applied to natural populations, a reasoned decision must be based on a benefit-risk assessment; there is no other path. According to the “responsible research and innovation” (RRI) policy framework promoted by the European Union (Wittrock et al., 2021), the mission of scientific research is not limited to producing knowledge; it must also ensure that the research and resulting applications are in line with society’s needs, interests and values. In this spirit, characterizing the various risks and benefits associated with CRISPR homing gene drive is part of the scientific enterprise. Identifying the risks can help to design safer technologies and to inform public debate and decision-makers. Risk considerations have been omnipresent for CRISPR homing gene drives. As soon as the first papers describing this new technology were published in 2015 (Gantz, Jasinskiene, et al., 2015; Gantz and Bier, 2015), risks were highlighted by the researchers themselves who developed the technology, as well as others (Akbari et al., 2015; Esvelt et al., 2014). Since then, the ethical questions raised by CRISPR homing gene drives have not faded away. A quick PubMed search reveals that currently in the scientific literature more papers are being published about the risks associated with CRISPR homing gene drive than about new technological developments.

In their report issued in 2016, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine of the United States of America concluded that “it is essential to examine each gene drive on a case-by-case basis” (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). We agree with this statement but would like to add that, given the issues at stake, it can also be useful to combine such case-by-case assessments with a general overview of the risks and benefits (Moro et al., 2018). In particular, the slippery slope argument (Van Der Burg, 1992), that authorizing a specific application for gene drive may then pave the way for others to be accepted, can be framed more precisely when one has a clear view of the risks and benefits that extend beyond the initial application in question.

Ultimately, the risks and benefits associated with gene drive technologies should be compared to the ones associated with other pest control methods (insecticides, wetland removals to control mosquitoes …), but this goes beyond the author’s expertise and would require a multidisciplinary study. The present article focuses on the general risks associated with CRISPR homing gene drive technology. The benefits are reviewed elsewhere (J. Champer, Buchman, et al., 2016; Esvelt et al., 2014). This article does not cover existing regulations of CRISPR homing gene drive (Genetic Literacy Project, 2025) nor ongoing discussions in various countries on how to regulate this biotechnology. After a brief description of the technology, we examine the limitations and risks associated with CRISPR homing gene drive.

2. CRISPR homing gene drive technology

2.1. The term “gene drive”

Gene drive is a broad term that can designate both natural processes and biotechnologies that can bias genetic inheritance (Alphey et al., 2020). We note, however, that some scientists prefer to restrict this terminology to human-made constructs, as in its initial definition (Agren and A. G. Clark, 2018; Esvelt et al., 2014; Wells and Steinbrecher, 2022). Several international bodies, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) or the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), clearly make the distinction with the use of the term “Engineered Genes Drives” (Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2024; IUCN, 2024).

Interestingly, the French term for gene drive, “forçage génétique” (literally meaning “genetic forcing”)—coined by Eric Marois, a researcher who works on mosquito gene drives (Herzberg, 2016)—, only refers to the biotechnology, and not to natural phenomena. It also conveys the idea of compelling and coercing. Meanwhile, the communication services of the non-governmental organization “Target Malaria” is currently promoting the use of an alternative, more benign, French term, “impulsion génétique” (https://targetmalaria.org/fr/notre-mission/comment-cela-fonctionne/).

Gene drive increases the probability that a particular genetic element will be transmitted to the offspring, thus allowing the propagation of a suite of genes and mutations throughout a population (Esvelt et al., 2014). The advantage in transmission can also allow genetic elements with fitness disadvantages (“selfish-DNA”) to spread through the population. Several types of CRISPR homing gene drives have been designed over the years (Raban et al., 2023; G.-H. Wang et al., 2024). Here we focus on the technique that has received the most attention and that is currently the most developed, CRISPR homing gene drive, named here for short “gene drive”.

2.2. Molecular mechanisms

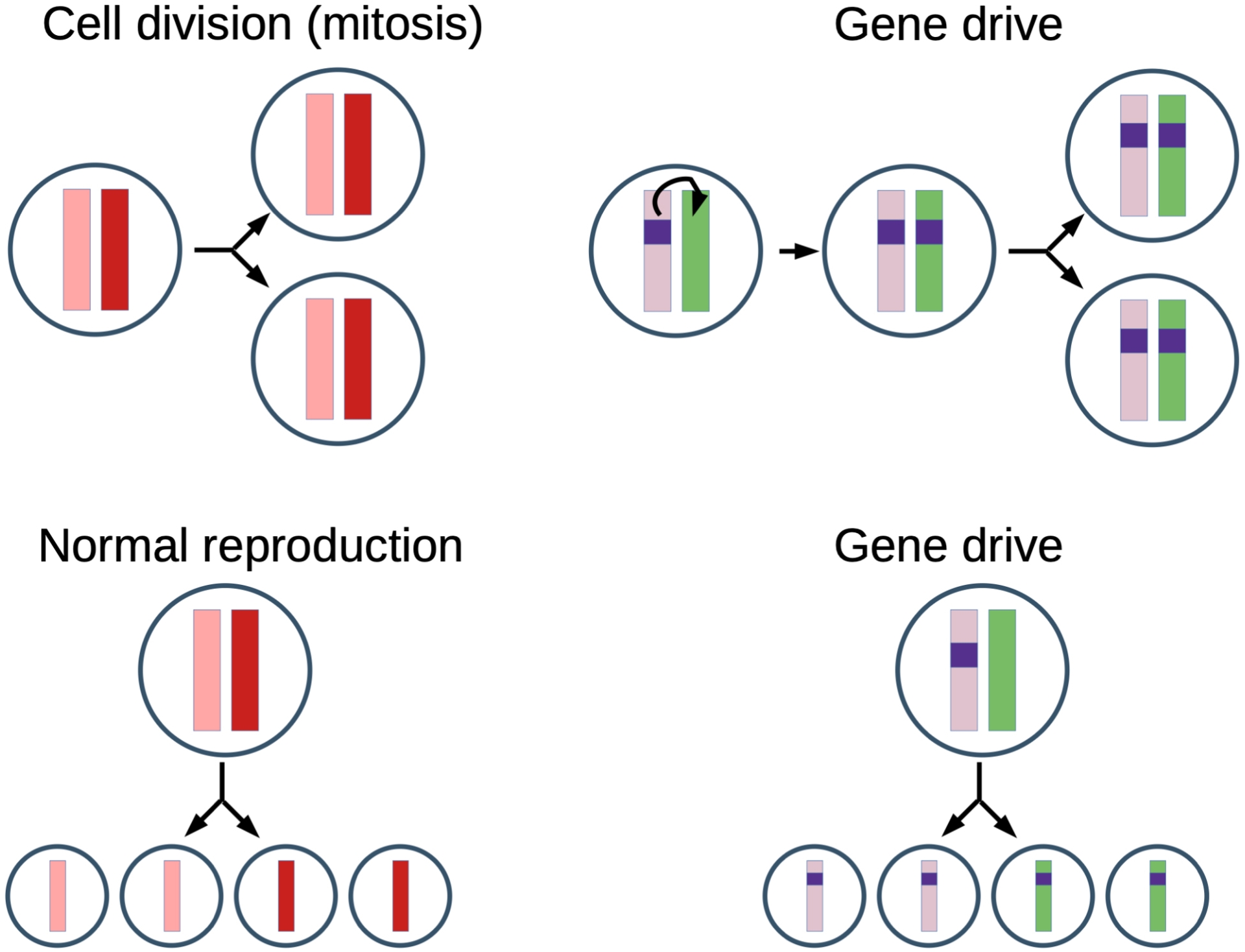

Gene drive technology relies on a piece of DNA, named “gene drive element”, that is inserted within a chromosome and that has the ability to copy itself at the same location on the other paired chromosome (Esvelt et al., 2014). This DNA piece contains several components that give rise to an active CRISPR-Cas9 system: a gene encoding the Cas9 protein, a gene encoding a guide RNA that targets a site located on the paired chromosome where the gene drive element will insert, other genes if necessary (such as a gene conferring resistance to a pathogen) and flanking regions that are identical to the ones adjacent to the guide RNA target site. All these components allow the formation of Cas9-guide RNA molecular complexes that can cut DNA at the target site. Then, homology-directed repair can lead to a copy of the gene drive element on the other paired chromosome. In most cases, the Cas9 gene is expressed in the germline, so that germline cells end up with a copy of the gene drive element on both of their paired chromosomes, and thus produce gametes that all harbor the gene drive element (Figure 1). As a consequence, all the progeny of a gene drive individual are expected to carry the gene drive element, as opposed to standard Mendelian genetics where a given allele present in one parent is received on average by 50% of the progeny. Theoretical modeling indicates that if gene drive individuals are released at a small frequency in a wild population, about 10–15 generations are sufficient to obtain a population contaminated at 100%, which corresponds to a couple of years for many insect species (Deredec et al., 2008).

CRISPR homing gene drive technology relies on a piece of DNA, named “gene drive element”, that has the ability to copy itself onto the other paired chromosome. In diploid individuals (left), the two paired chromosomes are inherited by both daughter cells after cell division, and segregate individually in gametes after meiosis, so that germline cells produce 50% of gametes with one chromosome and 50% of gametes with the other paired chromosome. With CRISPR homing gene drive, the gene drive element (dark blue rectangle) copies itself onto the other paired chromosome. The germline cell thus generates 100% of gametes that carry the gene drive element.

Gene drive can spread two types of mutations. On the one hand, it can spread genes of interest that have been introduced into the gene drive element, such as genes encoding antibodies directed against the malaria parasite vector Plasmodium falciparum, conferring resistance to it (Gantz, Jasinskiene, et al., 2015) or genes that would reverse pesticide resistance (Guichard et al., 2019). On the other hand, the insertion of the gene drive element itself can create the desired mutation. For example, gene drive elements were inserted at the doublesex locus in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes, making females sterile while not affecting males. The later gene drives were found to eradicate populations maintained in small cages (Kyrou et al., 2018) as well as larger, age-structured populations in bigger indoor cages within a year (A. Hammond, Pollegioni et al., 2021).

2.3. Applications

Two approaches are envisioned for gene drive, modification and suppression (Naidoo and Oliver, 2024). The goal of the modification approach is to spread a desired trait within a population. The expected endpoint is a population where 100% of its members carry the gene drive element. In contrast, the goal of the suppression approach is to reduce or eliminate a target population. Here the gene drive introduces genetic changes that cause sex-specific sterility, sex-ratio distortion, or other traits that decrease reproductive success, leading to population collapse. The suppression approach is currently more advanced than the modification approach, as it is easier to find genetic changes that alter fertility and survival than some that introduce desired, specific traits such as resistance to given pathogens in host insects, preventing them from being disease carriers (Gantz, Jasinskiene, et al., 2015), or insecticide susceptibility (Kaduskar et al., 2022). While some researchers have compared the modification approach with insecticides and the suppression approach with vaccines (Naidoo and Oliver, 2024), we would like to note here that these analogies convey incorrect ideas about associated risks. In contrast to vaccines, the final population after a modification drive still carries a gene drive element that is susceptible to mutate and incidentally pass onto another population. And in contrast to insecticides, stopping the release of suppression drive individuals is not sufficient to stop the gene drive. These points will be further developed in Sections 5.3 and 4, respectively.

A wide range of applications are envisioned for gene drives, not only in public health, but also in agriculture and conservation biology (Esvelt et al., 2014). Gene drive may help control or eliminate vector-borne diseases by targeting disease-carrying organisms, in particular mosquitoes for malaria, dengue, Zika, and chikungunya. This technology could also offer potential solutions to control insect pests (fruit flies, locusts, etc.) that damage crops or affect livestock. Gene drive has also been proposed to reintroduce susceptibility genes in weeds, to make herbicides effective again (Neve, 2018). Finally, gene drives could help protect endangered species by controlling invasive species or by introducing beneficial traits to at-risk populations (Rode, Estoup, et al., 2019).

2.4. Current status

In the laboratory, gene drive systems have been engineered in yeasts and various sexually reproducing animals including flies, mosquitoes and mice (Table 1). Applying gene drives to plants is challenging for several reasons. First, many plants reproduce vegetatively, via tubers, cuttings, etc. or through self-pollination, thus limiting the spread of a gene drive. Second, unlike insects or rodents, plants usually have long life cycles, slowing down the spread of a gene drive. Third, many plants have polyploid genomes, making gene drive inheritance harder to control. Fourth, homology-directed repair, which is necessary for the gene drive element to copy itself, does not appear to be as frequent in plants as in animals (Gorbunova and Levy, 1999; J.-F. Li et al., 2013). Recently, other types of gene drives, which are not “homing” and do not rely on homology-directed repair, have been developed in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Y. Liu et al., 2024; Oberhofer et al., 2024). These are not examined in this study.

List of species in which CRISPR homing gene drive has been demonstrated

| Taxonomic group | Species | References |

|---|---|---|

| Flies | Drosophila melanogaster | Gantz and Bier (2015) |

| Mosquitoes | Anopheles stephensi | Gantz, Jasinskiene, et al. (2015) |

| Mosquitoes | Anopheles gambiae | A. Hammond, Galizi, et al. (2016) |

| Yeasts | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | DiCarlo et al. (2015) |

| Yeasts | Candida albicans | Shapiro et al. (2018) |

| Mammals | Mus musculus | Grunwald et al. (2019) |

| Mosquitoes | Aedes aegypti | M. Li et al. (2020) |

| Mosquitoes | Culex quinquefasciatus | Harvey-Samuel et al. (2023) |

| Flies | Drosophila suzukii | Yadav et al. (2023) |

| Flies | Ceratitis capitata | Meccariello et al. (2024) |

Studies are presented in chronological order. Only the first published study for each species is mentionned.

To date, no gene drive has been released in wild populations. In November 2018, the 195 states that are signatories of the Convention on Biological Diversity, a multilateral treaty (not ratified by the USA) adopted a text indicating that the release of gene drive organisms in the wild must occur after obtaining “the free, prior and informed consent of indigenous peoples and local communities”1 .

“Risk” and “danger” are two words that are often confused. Danger refers to an inherent hazard or threat posed by a technology or process, regardless of probability, while risk refers to the likelihood of an adverse event occurring due to a specific action or technology, often expressed as a combination of probability and impact. Danger focuses on the potential severity of harm if the event occurs, while risk accounts for the likelihood of the event. Regarding gene drive, risk assessment should evaluate potential positive and negative consequences at various levels, including the target population, non-target populations, ecological effects, and socio-economic impacts. Because likelihoods are extremely difficult to estimate for gene drives, especially in the general case, we chose here not to evaluate probabilities but to characterize the various possible unintended and adverse outcomes of gene drive. We therefore use the term “risk” in a broader sense. We first examine scenarios where the technology may fail or may fail to be contained. Then we explore four types of adverse scenarios: (a) ecological risks, where the gene drive would have unintended consequences at the level of the target population, the other species or the ecosystem; (b) sociological risks associated with governance and public perception; (c) risks associated with experimentation; and (d) risks associated with malevolent usage.

3. Technical risks

As for technical risks, we consider here cases where the proposed biotechnology would not be as efficient as planned, and would not lead to the expected benefits. Such cases do not truly constitute adverse events, but simply failures.

3.1. Cryptic species

Cryptic species correspond to interbreeding individuals that are morphologically similar to a given species but are unlikely to hybridize with the members of this other species, for various reasons (incompatible behaviors, different ecological niches, physiological incompatibilities, etc.). In practice, this means that one species name refers to two or more reproductively isolated species (Bickford et al., 2007). As a consequence, a gene drive targeting a particular species cannot reach the cryptic species. Even if the gene drive element is designed to be able to insert into the genome of the cryptic species, it will not do so because released animals—and their progeny—will not hybridize with the individuals belonging to the cryptic species. For gene drives to spread within cryptic species, individuals able to mate with the cryptic species must be released.

Cryptic species are not rare in the Anopheles genus. In Western Kenya, several cryptic species of Anopheles mosquitoes, which are susceptible to transmitting malaria, have been recently identified using molecular markers (Zhong et al., 2020). The high number of cryptic species challenges vector control strategies targeting Anopheles mosquitoes.

In the case of suppression drives in mosquitoes, the successful elimination of a population targeted by a gene drive could leave an empty ecological niche that a cryptic species of mosquitoes could fill. This could thus lead to the expansion of this cryptic species. Under such a scenario, the initial gene drive would fail. Additional gene drives, constructed into the genomic background of the cryptic species (so that they can reach them via mating), would have to be used on top of the initial one to try to eliminate the cryptic species. Observations in the southwest Pacific suggest that Anopheles species diversity can hamper vector control strategies (Russell et al., 2013). Repeated spray of insecticides led to the disappearance of the most biting mosquitoes Anopheles punctulatus and Anopheles koliensis. However, Anopheles farauti populations went back to pre-spray levels within a few years, and replaced the populations of A. punctulatus and A. koliensis. This was apparently due to the evolution of a new, adapted behavior: avoiding insecticide exposure, by blood-feeding early in the evening and outdoors. Conversely, in another setting, a two-year longitudinal study in urban Singapore found that an intensive Wolbachia-based suppression of Aedes aegypti populations did not lead to niche replacement by the other mosquito species Aedes albopictus (Wong et al., 2025). These two examples highlight the difficulty of predicting the dynamics of natural populations of cryptic species and closely related species in response to control measures. To devise successful gene drive strategies, it is important to examine breeding habitats and habits for the target species and to look for possible cryptic species.

3.2. Gene drive resistance

Target populations might evolve resistance to the gene drive, either via resistance alleles already present (standing genetic variation) or via new mutations (Drury et al., 2017; Unckless et al., 2017). The molecular mechanism of gene drive propagation involves a Cas9-induced DNA break that is repaired by homologous recombination (see Section 2.2). However, if the cut is not repaired by homology-directed repair, non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) and microhomology-mediated end-joining (MMEJ) events can change the sequence of the target site. As a result, the mutated target site is no longer recognized by the guide RNA and thus constitutes a resistance allele. Additionally, when a gene drive allele is inherited from the mother, the Cas9/guide RNA complexes deposited in the egg can cut the wild-type male DNA before it comes close to the female DNA, precluding homology-directed repair, and this can generate resistant alleles (Bishop et al., 2022). The evolution of resistance alleles represents a major obstacle to successful applications of gene drive technology (Carrami et al., 2018; A. M. Hammond et al., 2017; Unckless et al., 2017).

So far, four strategies have been explored to avoid gene drive resistance. The first one is to use multiple guide RNAs within the gene drive construct, each targeting a nearby site (J. Champer, J. Liu, et al., 2018; J. Champer, Yang, et al., 2020) or with guide RNAs targeting both the wild-type and the most common resistance alleles (Bishop et al., 2022). Even if one site gets mutated, the other one(s) or the mutated site can still be used by the gene drive element to insert itself. Experiments using Drosophila show that the addition of a second guide RNA can indeed diminish the resistance rates (J. Champer, J. Liu, et al., 2018). The target sites should be chosen relatively far apart to prevent mutations at one site from converting an adjacent target site into a resistance allele. Interestingly, increasing the number of guide RNAs cannot ameliorate gene drive efficiency indefinitely. This is because guide RNA additions are associated with larger gene drive elements, and as homology arms are further apart, the efficiency of homology-directed repair is reduced (S. E. Champer et al., 2020). Theoretical work indicates that, depending on the type of drive and various performance characteristics, the optimal number of guide RNA targets varies from two to eight (ibid.). Furthermore, finding several guide RNA target sites (with no off-targets) within a short genomic region can be difficult for populations with high genetic diversity, such as A. gambiae (J. Champer, J. Liu, et al., 2018).

A second approach is to restrict the expression of the Cas9 gene or the guide RNAs to a developmental stage when homology-directed repair is predominant and end-joining pathways are nonexistent (ibid.). This strategy requires specific promoters that may not be available for all species (Du et al., 2024). Furthermore, it does not fully eliminate resistance because incomplete homology-directed repair can still create small insertions and deletions that confer resistance (J. Champer, J. Liu, et al., 2018).

A third strategy is to target a gene encoding an essential protein, and rescue it by providing within the drive element a modified gene encoding the same essential protein using different codons, so that it is not cleaved by the drive. Resistance alleles are expected to disrupt the function of the target gene, reduce fitness and, consequently, be eliminated from the population over time. Targeting a haplolethal gene allows the rapid elimination of resistance alleles, since heterozygous individuals carrying the resistance allele are lethal. A rescue drive with two guide RNAs targeting the haplolethal gene RpL35A, encoding for a ribosome protein, was successfully implemented in Drosophila (J. Champer, Yang, et al., 2020). However, engineering similar rescue drives in non-model species is challenging for several reasons: identifying a bona fide haplolethal target gene in a non-model species genome can be fastidious; the rescue can be difficult to implement; and recoded regions may not fully prevent homology-directed recombination (J. Chen et al., 2023). An easier path is to target a haplosufficient gene. Compared to haplolethal genes, these are more numerous in genomes (Deutschbauer et al., 2005). In this case, the resistance alleles are eliminated more slowly, as they can be maintained in heterozygous, viable individuals. Such drives were constructed with one guide RNA in Anopheles stephensi (Adolfi et al., 2020) and with one or four guide RNAs in D. melanogaster (Hou et al., 2024; Kandul et al., 2021; Terradas et al., 2021), and all evolved resistance. In the most recent study with four guide RNAs (Hou et al., 2024), resistant individuals were found to carry a large deletion in the coding region of the targeted gene. This shows that targeting an essential gene does not suffice to prevent resistance alleles: the precise sequence targeted by the drive within the gene should be essential for the function of the protein.

A fourth approach is to target a highly conserved site, so that eventual mutations at the target site are deleterious and give no progeny. Kyrou et al. devised a clever gene drive system in A. gambiae with a single guide RNA targeting a highly conserved sequence that is essential for the function of the female-specific Doublesex isoform protein (Kyrou et al., 2018). Females that are homozygous for the gene drive are sterile and unable to bite, whereas males are fertile. This drive can thus disperse via males and via somatic heterozygous females. This drive was able to spread rapidly in cage populations, leading to the full elimination of all mosquitoes in 8-12 generations. Cas9-resistant variants appeared, but they did not block the spread of the drive, which is consistent with the fact that these Cas9-resistant alleles are expected to produce nonfunctional Doublesex isoform proteins and thus sterility. The Doublesex locus was also targeted recently by gene drive in D. suzukii, and all the few Cas9-resistant alleles that were detected similarly led to sterile females, indicating that they would not prevent the spread of the drive (Yadav et al., 2023). So far, this last approach seems to be the most effective one to prevent resistance. But it only applies to suppression drives, and it is still unclear whether it would be resistance proof in broader settings and native ecological conditions (Kyrou et al., 2018).

Ten years after the first proof-of-principle experiments (Gantz, Jasinskiene, et al., 2015; Gantz and Bier, 2015), gene drive technology is still not ready for release. For a gene drive to be successfully implemented in the wild, further technical work is required to make sure that resistance will not evolve and that the mating system of the targeted population will allow the drive to spread to all individuals.

4. Risk of ineffective mitigation

In case of unintended effects following a gene drive release, one may want to stop the drive. However, halting a drive is not as easy as with insecticides, where stopping treatment will prevent further spreading and should ultimately put an end to the damage. A released gene drive is likely to continue to spread within the targeted population, even if releases have stopped. If gene drives are to be implemented in the wild, it is important to have effective methods to be able to stop them if necessary.

Two types of “reversal drives” or “brakes” capable of overwriting or neutralizing an existing gene drive have been proposed (Wu et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2020). They are themselves gene drives that encode guide RNAs but not the Cas9 protein. One type of reversal drive inserts itself within the Cas9 gene of the initial gene drive element and inactivates it. The inactivated drive thus remains in the genome. The other type of reversal drive contains two guide RNA genes that allow the excision of the entire initial gene drive element and its replacement with the reversal drive that is devoid of the Cas9 gene. Theoretical models show that the temporal dynamics of gene drives and reversal drives are complex and depend on multiple factors (Girardin et al., 2019; Rode, Courtier-Orgogozo, et al., 2020; Vella et al., 2017). In certain conditions pertaining to the relative fitness of the drive, the reversal drive and the wild-type alleles, the moment at which reversal drives are released, and the heterogeneity in the spatial distribution of the population, some drives may be unstoppable.

Another strategy is to use a transgene inherited in a Mendelian fashion and encoding anti-CRISPR proteins (Basgallet al., 2018; D’Amato et al., 2024; Taxiarchi et al., 2021). Anti-CRISPR proteins are natural molecules found in phages that are able to inhibit Cas9 activity and can thus neutralize the activity of a gene drive. This method does not involve DNA breaks and repair events, so off-target effects are minimal and the outcome is more predictable than with reversal drives. In large-size cages containing age-structured populations of mosquitoes, the spread of a suppression drive targeting the doublesex locus was stopped by releasing anti-drive males at a 30% allelic frequency every three to four days for several weeks, until the termination of the experiment (D’Amato et al., 2024). Sequencing at various time points revealed that functionally resistant alleles were not selected over the course of the experiment. However, drive alleles were still present after more than 200 days, raising uncertainty about whether they would manage to spread again had anti-CRISPR male releases been paused for several weeks. These findings indicate that in a complex, near-natural environment, continuous releases of anti-CRISPR transgenic individuals would be required to effectively counteract the spread of a potent suppression gene drive and prevent the elimination of the target population. Further experimental validation and mathematical modeling, particularly in spatially heterogeneous environments, will be necessary to assess the range of conditions allowing this anti-drive strategy to successfully mitigate gene drive propagation.

Overall, the anti-drive approach appears as a more effective countermeasure against gene drives than the reversal drive strategy. Further research will be needed to ensure its safety and efficacy across diverse ecological and genetic contexts. An important issue with all the proposed countermeasures so far is that they require the release of new individuals and close monitoring of the target population and ecosystem. This means that if an initial gene drive release proves problematic, local communities are condemned to pursue remediation actions with the research team. This may cause additional risks, and highlights the fact that sociological factors play an important role in the debate around gene drives (see Section 6).

5. Ecological risks

Even if gene drives may not be as effective as anticipated (see Section 3), they may still have unintended effects on the target population, on other species, or on entire ecosystems. While the molecular-level consequences of gene drives can often be predicted with relatively good precision, their impacts become increasingly difficult to foresee as we move to higher levels of biological organization—from phenotypic traits within the target species to broader ecological interactions—, due to the growing complexity and interconnectedness of these systems.

5.1. Complexity of the environment and unpredictability of the gene drive element

What makes ecological risks associated with gene drives especially difficult to apprehend is two-fold. First, gene drives are designed to act in native ecosystems, where multiple species interact with each other, as opposed to “classical” genetic engineering of domesticated species, which usually live in standardized environments isolated from their wild counterparts. Second, the gene drive element is a self-replicating genetic element that is extremely labile given its design: many types of mutations can occur in the gene drive element and transform an original drive into a new one, with novel potential adverse effects on the phenotype of the drive-carrier animals and on ecosystems. Indeed, a new cargo gene may insert into the element, bringing new phenotypic potentialities such as insecticide resistance or increased attraction to humans. Furthermore, mutations in the sequence of the guide RNA gene can change the cut site, and the drive may insert at a new position in the genome, using as homology arms repeated sequences distributed across genomes.

Given the infinitesimal size of the gene drive element compared to the rest of the genome, mutations are expected to be more frequent outside of the gene drive element than within. Nevertheless, if mutations occur in the gene drive cassette, these mutations, compared to mutations occurring at other positions in the genome, are likely to have larger consequences at the level of mosquito populations. This is because gene drives have a higher ability to spread in populations due to their non-Mendelian inheritance. For example, insecticide resistance alleles usually decrease mosquito fitness in the absence of insecticides, and are thus rapidly eliminated in the absence of insecticide (Kliot and Ghanim, 2012). But if a resistance gene inserts within a gene drive, then its non-Mendelian inheritance can compensate its detrimental fitness effect in untreated regions, and so lead to increased spread of the resistance.

Regarding the range of mutations, it is interesting to compare gene drive technology with Wolbachia-based methods for mosquito control (G.-H. Wang et al., 2024). The latter strategies also rely on the spread of self-replicating genetic elements—the bacterial symbionts Wolbachia—, which are susceptible to mutations as well. Regarding mutations in the Wolbachia genome, for them to persist over multiple generations, they must be compatible with the survival and function of the symbiont, which depends on complex biological processes such as metabolism, cell division, and migration. Therefore, the range of possible persisting mutations appears to be more limited for Wolbachia than for gene drives. With respect to possible phenotypic effects of future mutations, comparing those in Wolbachia with the ones in gene drive elements is tricky. Wolbachia has been infecting insects for many millions of years (Sanaei et al., 2021) so that it has evolved strong abilities to alter the insect’s phenotype. But on the other side, insects have also evolved means to counteract Wolbachia effects. In contrast, the gene drive element encoding the Cas9 protein and guide RNAs is a new self-replicating entity, never encountered before by insects.

Overall, the risk of gene drives adopting new functions is higher for modification drives than for suppression drives, because modification drives are maintained within the target population whereas the suppression drives are designed to be eliminated together with the target population. Gene drive elements, whether in their intended form or following mutations, may induce unexpected changes in the target species, potentially impacting other species and the broader ecosystem.

5.2. Disruption of ecosystems

The rapid spread of gene drives can lead to unanticipated ecological impacts. Suppression drives are particularly worrisome because they intend to eliminate an entire species from an ecosystem. The concern here is the same as for the use of insecticides or other methods to get rid of a given species. Suppressing one species may cause cascading effects, altering predator–prey relationships and food web stability. The removal of all the cats on Port-Cros island in France led to rat proliferation, whereas the stabilization of the cat population at around 250 individuals on the neighboring Le Levant island was associated with controlled rat populations (A. Atlan, personal communication). Furthermore, a species considered to be invasive or detrimental by some communities may actually be regarded as valuable by others (Carroll, 2011; Davis et al., 2011). For example, kudzu in Japan is a native plant considered beneficial for erosion control, animal fodder, and even traditional medicine. In contrast, in the United States of America it is most commonly seen as a notorious invasive species, growing uncontrollably, although there are a few vocal kudzu’s supporters (D. H. Alderman and D. G. Alderman, 2001). The target species may have unknown ecological functions in the ecosystem, and its elimination may thus fragilize the ecosystem. For example, invasive black rats may be responsible for dispersing seeds of native plants, a function previously undertaken by the native rodent species replaced by black rats (Shiels and Drake, 2011). Eliminating black rats may then affect the dissemination of native plants.

The goal of eliminating an invasive species might be to return to an ancestral equilibrium similar to the one prior to the invasion. But local eradication of an invasive species leaves an empty ecological niche that can trigger diverse cascading trophic effects on the distribution and abundance of multiple other species in direct and indirect interaction with the eliminated species (Zavaleta et al., 2001). For instance, the removal of feral goats and pigs from Sarigan Island, a US territory in the northwestern Pacific, triggered the proliferation of the previously undetected invasive vine Operculina ventricosa, which subsequently spread within the ecosystem (Kessler, 2002). In certain conditions, eradicating an invasive species can even make the system more susceptible to new invasions (David et al., 2017).

Currently, gene drives are primarily being studied by geneticists and molecular biologists. However, given their potential impact on ecosystems, it is crucial for ecologists and evolutionary biologists to actively engage in research about the possible ecological consequences of gene drive.

5.3. Propagation to non-target populations

CRISPR homing gene drives are expected to be highly invasive in nature (Noble et al., 2018). A well-documented example of global dissemination is the natural transposable element named the P element, which rapidly spread across all natural populations of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster worldwide during the mid-20th century, probably following its horizontal gene transfer from another Drosophila species (Anxolabéhère et al., 1988; J. B. Clark and Kidwell, 1997). A primary concern is thus that gene drives designed to target a specific population may contaminate other populations of the same species. The longer the gene drive is present in the wild, the greater the risk. Here again, the risk is higher for modification drives than for suppression drives.

To control invasive black rats and house mice in New Zealand, gene drive approaches have been considered (Leitschuh et al., 2018; Prowse et al., 2017). Islands are not as isolated as they might appear. Genomic studies have shown that rodents can move between islands, often facilitated by human activities such as maritime transport (Sjodin et al., 2020). To develop population-specific gene drives, a potential strategy is to target unique DNA sequences present exclusively in the intended population (Esvelt et al., 2014; Sudweeks et al., 2019). However, this approach presents significant challenges, as it requires capturing the full extent of genetic variation across all natural populations, which is nearly impossible. Additionally, gene drives are susceptible to mutations (see Section 5.1), and may thus gain the capacity to spread in other populations, although they were not designed to do so.

5.4. Propagation to non-target species

Another risk is the propagation to closely related species. In fact, some gene drive strategies targeting the Anopheles species complex are intentionally designed to propagate across multiple closely related species, as several members of this complex serve as vectors for malaria transmission (Nolan, 2021). Targeting the highly conserved doublesex locus is a promising strategy for developing suppression drives in Anopheles mosquitoes (see Section 3.2). However, this ultraconserved sequence is found in several species of Anopheles and is also likely to be conserved in other closely related species. Using highly conserved sequences as target sites increases the risks of propagation to closely related species, even if they were not necessarily targeted initially.

Even if hybridization between two closely related species occurs very rarely, as long as it happens at some appreciable frequency, the risk of transmitting the gene drive to another species exists (Courtier-Orgogozo et al., 2020). The P element that had previously contaminated all natural populations of D. melanogaster is now invading wild populations of the closely related species D. simulans (Hill et al., 2016; Kofler, Senti, et al., 2018; Kofler, Hill, et al., 2015; Nascimento et al., 2020), and it probably started via an interspecific cross with D. melanogaster. Data indicate that hybridization and interspecific genome mixing occur sporadically between species previously thought to be reproductively isolated. For example, hybridization can occur between the black rat Rattus rattus and the Asian rat R. tanezumi (Lack et al., 2012), as well as between the fly pest species Drosophila suzukii and its close relative D. subpulchrella (Conner et al., 2017; Courtier-Orgogozo et al., 2020). Therefore, gene drives targeting these species are likely to end up in the closely related species.

In addition to hybridization, DNA can be naturally transferred from one species to another through horizontal gene transfer, mostly via viruses and microorganisms that can carry over pieces of DNA (Gilbert and Cordaux, 2017). Gene drive elements resemble homing endonuclease genes, which are natural transposable elements that can bias their inheritance by cutting and inserting themselves at targeted sites within genomes (Agren and A. G. Clark, 2018). A homing endonuclease gene targeting the cox1 mitochondrial gene has been found in multiple species of plants, fungi and green algae. Phylogenetic studies revealed that it has been transferred independently 70 times between 162 plant species involving 45 different families (Sanchez-Puerta et al., 2008). This suggests that genetic elements with a transmission advantage, such as gene drives, can possibly reach distantly related species by horizontal gene transfer. Notably, for a given gene drive construct to contaminate a distantly related species, six conditions should be met: (1) horizontal transfer; (2) expression of the Cas9 gene and the guide RNA gene in the new host; (3) presence of a target site in the host genome; (4) presence of flanking sites to allow the insertion of the gene drive element; (5) resistance of the gene drive to the host immune system; and (6) survival and reproduction of the contaminated individuals (Courtier-Orgogozo et al., 2020). In-depth examination of each of these conditions indicates that the probability of a gene drive element to contaminate another species is not null, especially because of the presence of repeated sequences in genomes that may facilitate homology-directed repair (ibid.).

In summary, the range of ecological risks highlighted here underscores the need to thoroughly assess the ecological role of the target species within its ecosystem. It also stresses the importance of involving ecologists in the planning and decision-making process before any intervention to try to minimize unintended consequences.

6. Sociological risks

Gene drive technology presents significant sociological risks that go beyond technical and ecological concerns. These risks stem from public perception and governance issues. As previously seen with COVID-19 vaccines during the pandemic, negative public perception can rapidly spread via social media (Rodrigues et al., 2023). One of the greatest risks is an unauthorized release of gene drive organisms into the wild, whether accidental or deliberate, because this could severely damage public trust in scientists, institutions or regulators (Esvelt, 2018; Min et al., 2018). If gene drives are overly hyped (Boëte, 2025), or perceived as being deployed recklessly or without full transparency, this could lead to increased skepticism toward genetic engineering and heightened public opposition to biology research activities in general, even those with clear potential benefits and little risk. Furthermore, this could undermine trust in public health in general, and thus reduce the effectiveness of outbreak prevention and control measures (World Health Organization, 2012).

If gene drives are released without proper engagement with local populations, affected communities may see gene drives as an unnatural disruption of their environment and may feel disempowered. This could lead to accusations of biocolonialism, where genetic technologies are imposed on vulnerable populations without adequate consultation or compensation. This issue is particularly acute for malaria control, where gene drive research is primarily conducted in wealthy countries, but intended for deployment in the Global South and especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Efforts are being made to involve local communities in Burkina Faso and to foster inclusive, well-informed discussions (Sykes et al., 2024). The “Mice Against Ticks” project in Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard islands represents an interesting example of how residents identified potential ecological consequences that were overlooked by researchers, highlighting the importance of community input (Buchthal et al., 2019). Non-scientists—such as local communities, farmers, or citizen scientists—can sometimes be extremely well informed about the various technical aspects and can contribute valuable knowledge and perspectives to scientific discussions. For example, to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires in Australia, modern land management strategies benefited from the integration of Aboriginal fire management practices, such as controlled burns (Ens et al., 2015).

Furthermore, gene drive organisms do not respect national borders: one country’s decision to use the technology could be seen as imposing risks on neighboring nations and could result in diplomatic incidents. This adds complexity to the development of international regulation, particularly with respect to decision-making and accountability (Beck, 2019). Currently, no international regulatory framework exists for gene drive technology.

To address the sociological risks associated with gene drive technology, scientists and policymakers must prioritize transparency, inclusivity, and active engagement with local populations. Public participation in the debate is essential but not sufficient. Researchers and policymakers should also be tolerant towards diverse perspectives: they should respect and take into account the views of others.

7. Risks associated with experimentation

No experimental manipulation is completely free of human error. The accidental release of just a few gene drive individuals during testing may lead to contamination in the wild. Biologists have been aware of this issue since the early days of gene drive research and have implemented a series of rules for laboratory research on gene drives (Akbari et al., 2015; Esvelt et al., 2014; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016; Oye et al., 2014). These include conducting research in regions where the target species is not present and cannot survive and reproduce, and using barriers and protocols more stringent than what is usually used for genetically modified organisms to prevent escapes. While standard scientific practice encourages preserving genetically modified organisms to allow replication and further research, it is considered that gene drive research makes an exception to this rule and that gene drive organisms should be appropriately discarded once an experiment is over.

Recently, Zapletal et al. proposed to use “biodegradable gene drives” for research (Zapletal et al., 2021). These gene drives encode for site-specific recombinase/transposases that will lead to excision of the gene drive element and reversion of the modified chromosome to a wild-type allele. Although these gene drives have not been tested experimentally, mathematical modeling indicates that strong homing biodegradable gene drives start to spread and then are eliminated. However, since these drives do not fully correspond to the ultimate gene drive applications, their practical relevance for laboratory studies and field trials remains uncertain.

A more common and safer strategy for gene drive research is to use split gene drives (Akbari et al., 2015; J. Champer, Chung, et al., 2019; W. Chen et al., 2024; Terradas et al., 2021). Unlike standard gene drives, where all necessary genetic components are present within a single construct, the Cas9 gene is inserted into one genomic location and the guide RNA and repair template are placed at another. Since the two components are not inherited together, the split gene drive is self-limiting: it can function within a controlled laboratory setting when both elements are present in an organism but cannot spread indefinitely in wild populations. This strategy of using elements with no autonomous replication ability resembles the use in virology research of pseudoviruses, which can infect only a single cycle of host cells (Xiang et al., 2022).

International discussions around gene drive research have not yet converged on a set of rules and guidelines to be respected worldwide. As of today, regulations vary between countries (Genetic Literacy Project, 2025). To our knowledge, there is no independent international body examining gene drive research projects before and after they are implemented.

8. Risks associated with malevolent usage

Let us now consider the possibility that gene drive could be malevolently used by states or non-state groups, for military or terrorist objectives. In theory, two types of biological weapons could be built based on gene drive: suppression drives that would target insect species necessary for agriculture (e.g. pollination) and modification drives that would render pest or disease-carrying insects resistant to insecticides or able to deliver toxins to humans.

The Biological Weapons Convention, which bans the development of offensive biological weapons, was signed by most countries in 1972 (United Nations, 1972). Ten states have neither signed nor ratified the treaty: Chad, Comoros, Djibouti, Eritrea, Israel, Kiribati, the Federated States of Micronesia, Namibia, South Sudan and Tuvalu (United Nations, 2019). Unfortunately, sporadic reports suggest that clandestine biological weapon development programs may still be underway in rival nations, despite their signature of the Biological Weapons Convention. Current data show that several terrorist groups, such as Aum Shinrikyo, the Islamic State and Al-Qaeda, have put efforts into developing biological weapons in the past (Danzig et al., 2012; Parachini and Gunaratna, 2022). Given the current situation, the danger associated with malevolent uses of gene drive technology should be examined seriously.

The use of biological weapon is intrinsically linked to the development of antidotes and vaccines, to make sure that the attackers and their allies are not affected by the biological weapon itself. Compared to standard biological agents that target humans directly—via pathogenic agents, such as toxins, viruses and bacteria—, the targets of gene drive technology in its current form are sexually reproducing animals with short life cycles, mostly insects and rodents. For special cases where gene drives would be designed to deliver toxins to humans, vaccines or antidotes would be required as for standard bioweapons. For other cases, it seems unrealistic to envisage trying to immunize certain insect/rodent populations prior to the release of a nefarious gene drive: as explained above, current available strategies to prevent a given gene drive from spreading (before or after it is released) are not spatially restricted and do not appear to be fully satisfactory. Alternatively, a possible usage of a rogue gene drive would be to target an insect species that is present in the enemy region, but not in the attackers’ region. Then, the main difficulties lie in using CRISPR to genetically modify the target insect species, and in maintaining and raising sufficient numbers of transgenic animals for future release. Releases can easily go undetected for insects, since they are very small. Overall, in the current state of knowledge, potential applications of rogue gene drives concern a small number of animal species, which display the following characteristics: they reproduce sexually, have a short life cycle, are necessary for agriculture (e.g. pollination) or act as pests or carriers of disease, are not present in the territory of the attacker, can be reared, bred and maintained in large number in the laboratory, and are amenable to effective CRISPR technology. In 2017, the Defense Advanced Research Products Agency (DARPA) in the United States of America allocated funding to address potential malevolent uses of gene drive and to develop defensive countermeasures. However, relatively few research articles deal with this topic, partly to avoid the dissemination of dangerous ideas. Esvelt and his colleagues have proposed to monitor at-risk regions via environmental sequencing, in order to detect gene drive elements in any species, and to launch immunizing reversal drives to counteract any drive element that would be found (Esvelt, 2018; Min et al., 2018). As long as several locations are sampled and a relatively large number of reads is obtained from the species of concern, sequencing is indeed bound to detect the gene drive. Additionally, a mosquito-borne toxin would probably be noticed from the clinical cases first. Immediate defenses would probably be insecticides, and medium-term ones may involve immunizing reversal drives. Designing such reversal drives is straightforward for the defender, but accomplishing transgenesis in the target species and releasing multiple reversal drive organisms in the wild to successfully stop the malevolent gene drive may still be burdensome (Esvelt, 2018). Overall, the monitoring and mitigation processes can be costly and difficult, especially in low-income countries and in areas experiencing political instability. Furthermore, immunizing reversal drives are not always guaranteed to work (Rode, Courtier-Orgogozo, et al., 2020).

Since one bottleneck in the building process of rogue gene drives is the insertion of the gene drive element in non-model insect species via CRISPR, a first step in limiting rogue gene drives would be to exclude from scientific papers the methodological details for applying gene drive to non-model species, as for the technical instructions to make nuclear weapons (Gurwitz, 2014).

9. Conclusions

This paper outlines four categories of risks associated with CRISPR homing gene drive, and reviews current perspectives on each. Given the issues at stake, it is important to carry out a general assessment of the risks and benefits associated with gene drive. As each gene drive application comes with its own specificity, it must undergo rigorous evaluation before any release is considered. When evaluating gene drives for mosquito population control, it is essential to carefully consider alternative technologies, such as Wolbachia-based approaches or long-lasting insecticidal nets (Boëte, 2025; G.-H. Wang et al., 2024). Importantly, the success of a future gene drive release should not facilitate subsequent deployments of the technology, a concern known as the slippery slope argument (Van Der Burg, 1992). Regarding the possibility of malevolent use of gene drive, we emphasize the need for deeper theoretical exploration and concrete preventive measures to enhance global security. As exemplified by the 1975 Asilomar conference (Cobb, 2025), ethical committees and self-regulations by scientists are probably not sufficient to protect against misuse. Moving forward responsibly with gene drive technology requires increased public awareness and strong political engagement. We hope that this work will help decision-makers to carefully weigh the potential benefits of this biotechnology against its risks, and that it will serve as a basis for public debate.

Abbreviations

| CBD |

Convention on Biological Diversity |

| CRISPR |

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| IUCN |

International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic acid |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the COMETS for general discussions about risky research. We thank C. Boëte, F. Graner, K. Esvelt and the anonymous reviewer for comments on the article. AI was used to improve the fluency of certain sections of the text.

Declaration of interests

The author does not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and has declared no affiliations other than their research organization.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Research Council under the European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013 Grant Agreement no. 337579) and by Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) under the project “ANR-24-CE13-0018-01”.

1 Decision 14/19. ‘Synthetic Biology’. Decision adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity.” (November 30, 2018). Online at https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-14/cop-14-dec-19-en.pdf.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0