1 Introduction

Single-molecule magnets (SMMs) are a class of coordination compounds that attract a great deal of scientific attention because they exhibit magnetic bistability at low temperatures [1]. These finite size (zero-dimensional) molecules possess a high spin ground state St and a magnetic anisotropy of the easy-axis type (negative zero-field splitting parameter D) which causes a slow relaxation of the magnetization at low temperatures resulting in a hysteresis of the magnetization of pure molecular origin [2,3]. Single-molecule magnets (SMMs) promise access to dynamic random access memory devices for quantum computing and to ultimate high-density memory storage devices in which each bit of digital information is stored on a single molecule [4]. The archetype of SMMs is the family of dodecanuclear manganese complexes, [Mn12O12(O2CR)16(OH2)4], Mn12 [2,5]. Since the discovery of the SMM behavior of Mn12, a lot of synthetic efforts have been devoted to the preparation of new molecules with an increased anisotropy barrier and a lot of fascinating new structural motives have been reported [6].

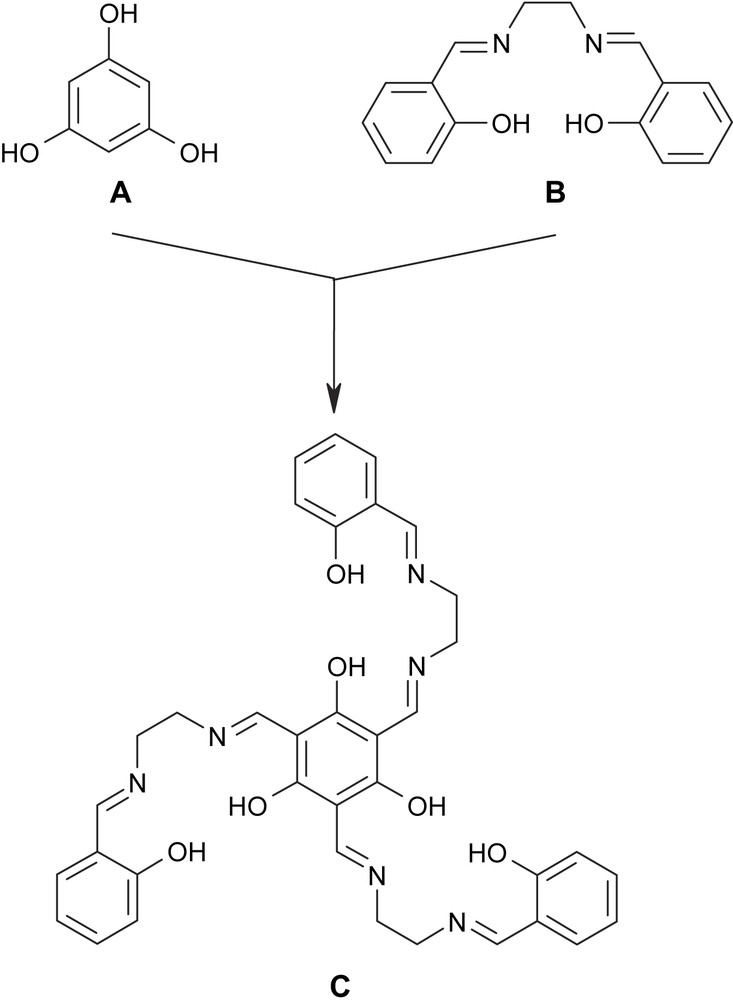

In order to meet the two necessary requirements for SMMs, we have designed the triplesalen ligand C (Scheme 1) which combines the phloroglucinol bridging unit A with the coordination environment of a salen ligand B [7]. We and others have shown that the phloroglucinol bridging unit A acts as a ferromagnetic coupler in trinuclear MoV and CuII complexes by the spin-polarization mechanism [8,9]. In order to introduce magnetic anisotropy we have been choosing a salen-like coordination environment which is known to establish a pronounced magnetic anisotropy by its strong ligand field in the basal plane [10,11]. A well studied example is the Jacobsen catalyst [(salen′)MnIIICl] (H2salen′ = (R,R)-N,N′-bis(3,5-di-tert-butylsalicylidene)-1,2-cyclohexanediamine) [12] which is a MnIII (S = 2) species with a zero-field splitting of D = −2.5 cm−1 [10,13]. In this respect, it is interesting to note that already a dimeric MnIII salen complex behaves as an SMM [14].

The hybrid–ligand triplesalen C comprising the bridging phloroglucinol A and of the coordination environment of a salen–ligand B.

Metal complexes of the salen ligand H2salen (=N,N′-bis(salicylidene)-ethylenediamine) and its derivatives have been studied for a long time in coordination chemistry [15,16]. The ability of metal–salen complexes to catalyze chemical transformations has been recognized for a variety of metal ions [17]. An important advantage of salen ligands for their use in catalysis is the opportunity for systematic variations of their steric and electronic properties. The discovery by Jacobsen, Katsuki, and coworkers that chiral MnIII salen complexes are effective catalysts for enantioselective epoxidation of unfunctionalized olefins [12,18] led to a revival of the coordination chemistry of salen ligands. A folded geometry of the salen ligand accompanied by the formation of a chiral pocket has been argued to be an essential element for their enantioselectivity [19–21]. For the asymmetric nucleophilic ring-opening of epoxides by chromium salen complexes a mechanism was established involving catalyst activation of both nucleophile and electrophile in a bimetallic rate-determining step [22]. Such a cooperative reactivity between multiple metal centers is a common feature in metallo enzyme systems [23]. By using covalently linked dinuclear salen systems not only the intramolecular pathway but also an intermolecular pathway was enhanced [24]. This observation “indicates that dimer reacts more rapidly with dimer, than does monomer with monomer” and “suggests that the design of covalently linked systems bearing three or more metal–salen units may be worthwhile” [25].

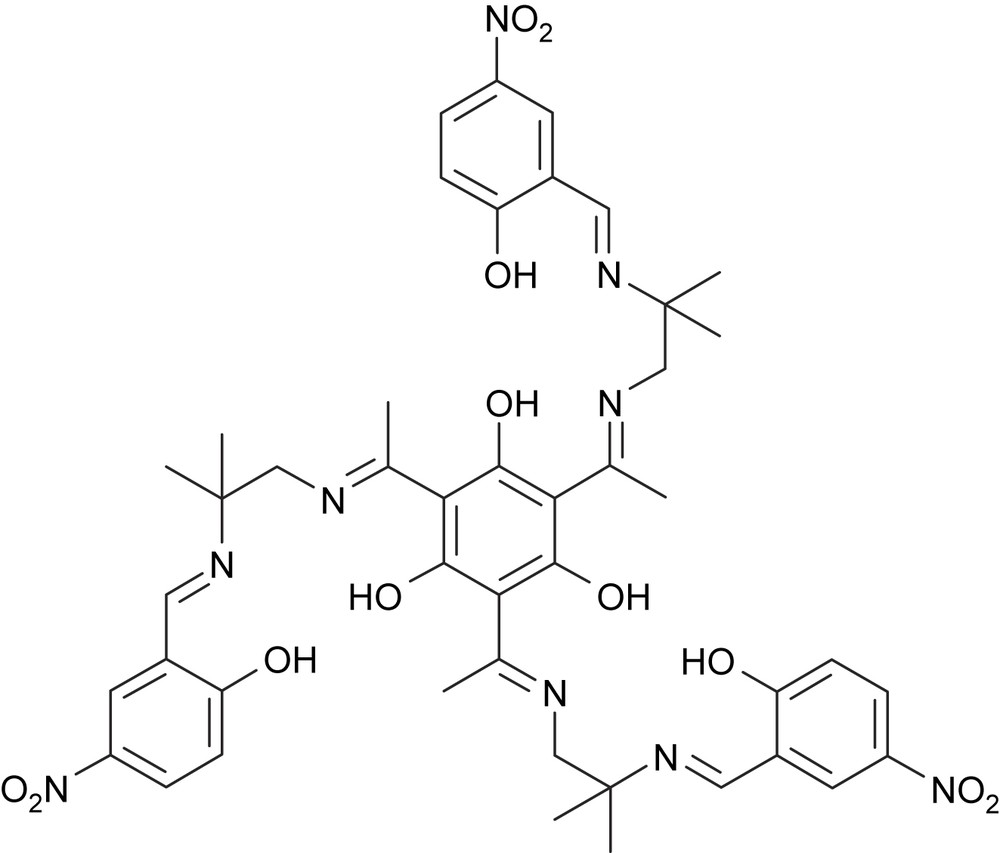

In a recent communication we described the successful synthesis of the first triplesalen ligand H6talen (= 2,4,6-tris(1-(2-salicylaldimino-2-methyl-propylimino)-ethyl)-1,3,5-trihydroxybenzene) and the structure of its trinuclear NiII complex [(talen)Ni3II] [7]. The analogous trinuclear CuII complex [(talen)Cu3II] exhibits ferromagnetic couplings between the three local S = 1/2 spins via the spin-polarization mechanism resulting in an St = 3/2 spin ground state [26].

Variation of the terminal substituents in triplesalen ligands provides a control of the electronic communication between the metal–salen subsites as demonstrated in a series of trinuclear nickel complexes [27]. Besides this electronic control, the variation of the terminal substituents results in different degrees of ligand folding which should allow for systematic investigations for enantioselective transformations.

In order to prepare magnetically as well as catalytically interesting complexes, we have started to investigate the manganese coordination chemistry of our triplesalen ligands. We have used the trinuclear MnIII triplesalen complex of the tert-butyl derivative as a building block for the synthesis of the heptanuclear complex [28]. This complex exhibits an St = 21/2 spin ground state and a sizable magnetic anisotropy and we could prove that MnIII6CrIII is indeed a single-molecule magnet. However, analysis of the temperature-dependence of the magnetic susceptibility of MnIII6CrIII revealed that the coupling of the MnIII ions in the triplesalen subunits is antiferromagnetic contrarily to the results found for CuII and MoV. Herein, we describe the synthesis, structural, and magnetic characterization of the first trinuclear manganese triplesalen complexes, namely (1) with (Scheme 2).

.

2 Experimental section

2.1 (1)

A solution of 25 mg (0.027 mmol) in CH3CN (10 mL) was added dropwise to a solution of 30 mg (0.083 mmol, 3.05 eq.) Mn(ClO4)2·6H2O in CH3CN (5 mL). Subsequently, solutions of 19 mg (0.25 mmol, 9.0 eq.) DMSO in CH3CN (1 mL) and 17 mg (0.17 mmol, 6.0 eq.) Et3N in CH3CN (3 mL) were added and the colour of the solution changes from yellow to brown. The solution is filtered and slow evaporation of the solvent yields 1 in the form of brown single-crystals which appear to be hygroscopic and analyzed as 1·3H2O. Yield: 21 mg (39%). UV–vis–NIR (DMSO): λmax/nm (ɛ/M−1 cm−1) = 365 (62 300); IR (KBr): /cm−1 = 3090w, 3010w, 2975w, 2919w, 2677w, 1623m, 1606m, 1565s, 1556s, 1485s, 1464m, 1435m, 1395m, 1382m, 1370m, 1332s, 1318s, 1280s, 1253m, 1195m, 1160m, 1148m, 1102s, 1017m, 950m, 850w, 819w, 795w, 679w, 669w, 643w, 624w. Anal. Calcd for 1·3H2O (C57H87N9O33Mn3Cl3S6; M = 1889.93 g mol−1): C, 36.23; H, 4.64; N, 6.67. Found: C, 36.29; H, 4.75; N, 6.84.

X-ray crystal structure analysis for 1: formula C57H81Cl3Mn3N9O30S6, M = 1835.84, black crystal 0.45 × 0.45 × 0.20 mm, a = 20.555(1), c = 24.141(1) Å, V = 8833.3(7) Å3, ρcalc = 1.380 g cm−3, μ = 0.731 mm−1, empirical absorption correction (0.734 ≤ T ≤ 0.868), Z = 4, trigonal, space group (no. 165), λ = 0.71073 Å, T = 198 K, ω and φ scans, 21 639 reflections collected (±h, ±k, ±l), [(sin θ)/λ] = 0.67 Å−1, 7273 independent (Rint = 0.042) and 4743 observed reflections [I ≥ 2σ(I)], 403 refined parameters, R = 0.092, wR2 = 0.306, maximum residual electron density 1.23 (−0.60) e Å−3, the DMSO molecules were refined with split positions, in addition geometrical constraints (DFIX and ISOR) were applied, hydrogen atoms calculated and refined riding.

The data set was collected with a Nonius KappaCCD diffractometer, equipped with a rotating anode generator. Programs used: data collection COLLECT [29], data reduction Denzo-SMN [30], absorption correction for CCD data SORTAV [31] and Denzo [32], structure solution SHELXS-97 [33], structure refinement SHELXL-97 [34].

3 Results and discussion

The ligand was prepared as described previously [27]. A solution of in CH3CN was added dropwise to a solution of Mn(ClO4)2·6H2O in CH3CN. Adding of solutions of DMSO in CH3CN and of Et3N in CH3CN resulted in a colour change from yellow to brown. The solution was filtered and slow evaporation of the solvent yielded compound 1 in the form of black single-crystals.

The ESI-MS spectra of CH3CN solutions of 1 show a weak peak at m/z = 356.0 (6%) corresponding to the trication . However, the presence of much stronger peaks at m/z = 434.1 (100%), 408.1 (97%), and 382.1 (42%) corresponding to , , and , respectively, clearly establishes the presence of coordinated DMSO molecules. The species with 4 DMSO, , is again of lower intensity at m/z = 460.2 (4%). The detection of and at m/z = 395.7 (16%) and 421.8 (63%), respectively, indicates easy substitution of coordinated DMSO molecules by solvent CH3CN molecules by considering that CH3CN with weak σ-donor and π-acceptor character is a bad ligand for high spin MnIII.

The FTIR spectrum closely resembled to that of the analogous trinuclear NiII complex [27]. The bands at 1102 cm−1 and 624 cm−1 are attributed to ClO4−. The splitting in the aromatic C–C stretching region in due to the inequality of the terminal and central phenolates which is absent in [(talen)Ni3II] and is retained in 1 at 1606 cm−1 and 1623 cm−1. The C–O stretching mode is shifted from 1299 cm−1 in to 1280 cm−1 in 1. Two additional bands at 1017 cm−1 and 1001 cm−1 are assigned to coordinated DMSO molecules (vide infra). The relatively small low-energy shift as compared to free DMSO (1100–1055 cm−1) indicates only weakly O-bonded DMSO molecules [35].

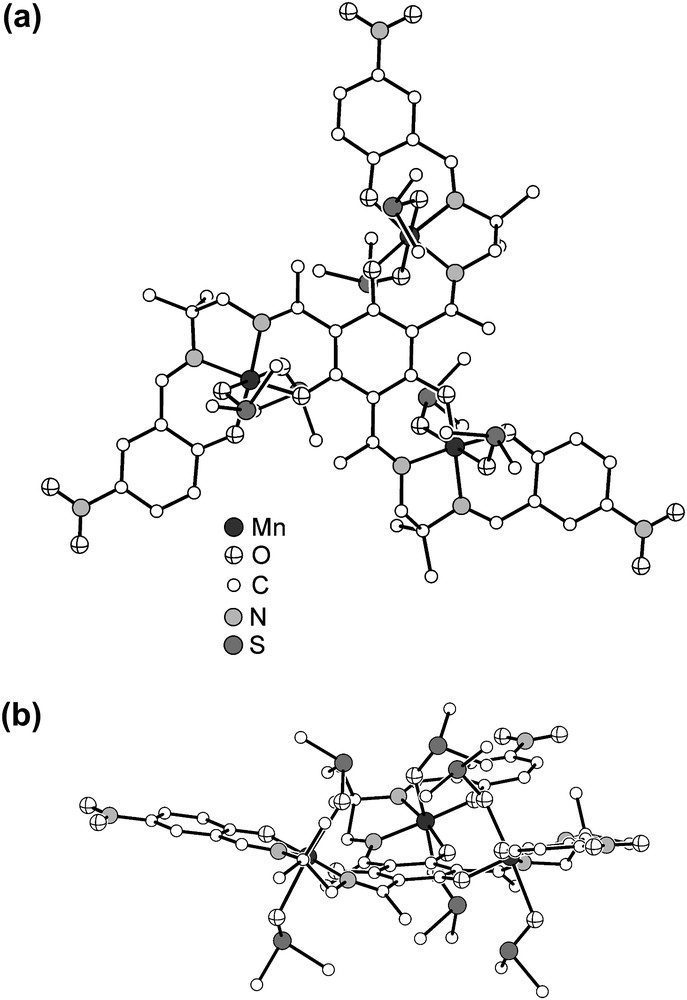

Compound 1 crystallizes as black hexagonal prisms. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis establishes the formulation of 1 as . The molecular structure of the trication is shown in Fig. 1. The trication resides on a crystallographic threefold axis. One sixfold-deprotonated triplesalen ligand coordinates three MnIII ions resulting in a typical salen-like square-planar coordination environment of the three MnIII ions. The overall octahedral coordination environment of each MnIII is completed by two DMSO molecules. The Mn–O distances of the central phenolates is 1.875(3) Å and of the terminal phenolates 1.891(3) Å, while the Mn–N distances of the imine donors are 1.961(4) Å (central) and 1.989(4) Å (terminal). The O-bonded DMSO molecules occupy the distant positions of the Jahn–Teller elongated MnIII octahedra. As evidenced by FTIR spectroscopy and ESI-MS, these DMSO molecules form only weak bonds with the MnIII ions resulting in disordered positions. Thus, the Mn–ODMSO distances (2.22(2) Å inside dish (vide infra); 2.34(1) Å outside dish) should be handled with great care. While the short Mn–ODMSO distance is in the typical range observed for O-bonded DMSO to MnIII [36], the longer Mn–ODMSO distance is outside the known range enforcing the conclusion drawn from the ESI-MS and FTIR measurements that at least one type of DMSO donors present in 1 forms only weak bonds.

Molecular structure of the trication in crystals of 1. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. (a) View perpendicular to the central phloroglucinol backbone; (b) view along the central phloroglucinol backbone.

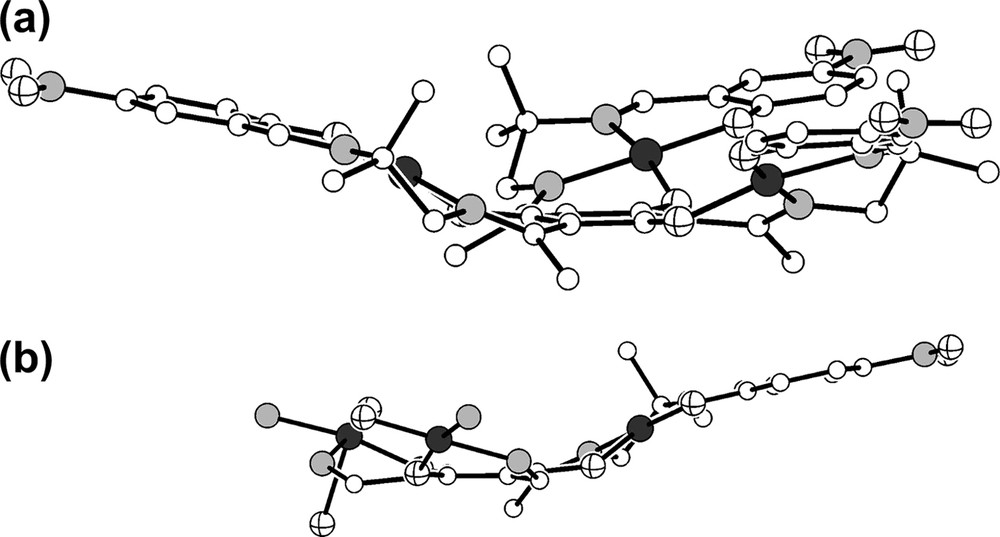

An important feature of the overall geometry of all trinuclear triplesalen complexes reported so far [7,26,27] is that they are not flat but exhibit various degrees of ligand folding. This structural characteristic is also observed in the molecular structure of 1. To better visualize the ligand folding, we have drawn the molecular structure of the trication in 1 without the DMSO molecules in Fig. 2a. Several geometric parameters allow for a quantitative description of this distortion. A simple measure is provided by the shortest distance d of the manganese ions from the best plane formed by the six carbon atoms of the central benzene ring of the phloroglucinol backbone which is 0.93 Å in 1. Although this value provides a quantitative measure for deviations from planarity, it gives no geometrical information for the influence on Mn–O bonding interactions, which are important for the exchange interactions mediated by the phloroglucinol bridging ligand. Additionally, the occurrence of folding in salen complexes has been recognized to be essential for enantioselectivity in catalytic transformation [19,20].

Molecular structure of the trication in crystals of 1. (a) For a better visualization of the ligand folding, the DMSO molecules have been omitted; (b) for a better impression, that the ligand folding occurs in different directions of the MnN2O2 plane, the organic parts of two manganese–salen subunits have been omitted.

A more sophisticated measure for the bending or folding of the ligands is provided by the angles formed between the MnN2O2 coordination plane and the two phenolate planes: α = 28.0° is the angle between the N2O2 plane and the benzene plane of the central phloroglucinol backbone, β = −18.6° is the angle between the N2O2 plane and the benzene plane of the terminal phenolate, and γ = 10.2° is the angle between the benzene planes of the central phloroglucinol and the terminal phenolates. This analysis provides a quantitative measure for the visual impression (Fig. 2a) that the folding is stronger at the central phenol unit.

Although these angles provide more detailed information on the structural distortion as compared to the distance parameter d, they cannot differentiate between a helical and a folding distortion [27]. In order to differentiate between ligand folding and helical distortion, we calculated the bent angle φ which has been introduced by Cavallo and Jacobsen [20]. The bent angle φ is defined by φ = 180° − ∠(M–XNO–XR) (XNO: midpoint of adjacent N and O donor atoms; XR: midpoint of the six-membered chelate ring containing the N and O donor atoms). By this definition, the bent angle φ describes mainly a folding distortion and only minor effects of a helical distortion. In 1, the values for the bent angles are φcentral = 29.7° and φterminal = −20.0°. The close similarity of φcentral to α and of φterminal to β clearly indicates that the main part of the distortion is due to ligand folding and not due to a helical distortion.

It is interesting to compare this behavior to the three trinuclear nickel triplesalen complexes reported previously [27]. The complex of the unsubstituted ligand [(talen)Ni3II] exhibits no uniform distortion of the three nickel–salen subunits except for strong helical distortions at the terminal phenolates. The nitro-substituted complex shows only small distortions while the tert-butyl substituted complex exhibits strong ligand folding at the central phenolates and less strong folding at the terminal phenolates. However, the folding of both ligand parts is directed to the same side of the NiN2O2 coordination plane resulting in an overall bowl-shaped geometry for . This is in contrast to 1, where the folding of the terminal phenolates is directed to the other side of the MnN2O2 coordination plane as compared to the folding of the central phenolates (Fig. 2b). This behavior is indicated by the different signs of α and β as well as of φcentral and φterminal. In a mononuclear salen complex, such a distortion would result in an overall step-like geometry, whereas in 1 this distortion results in an overall dish-like geometry (Fig. 2a).

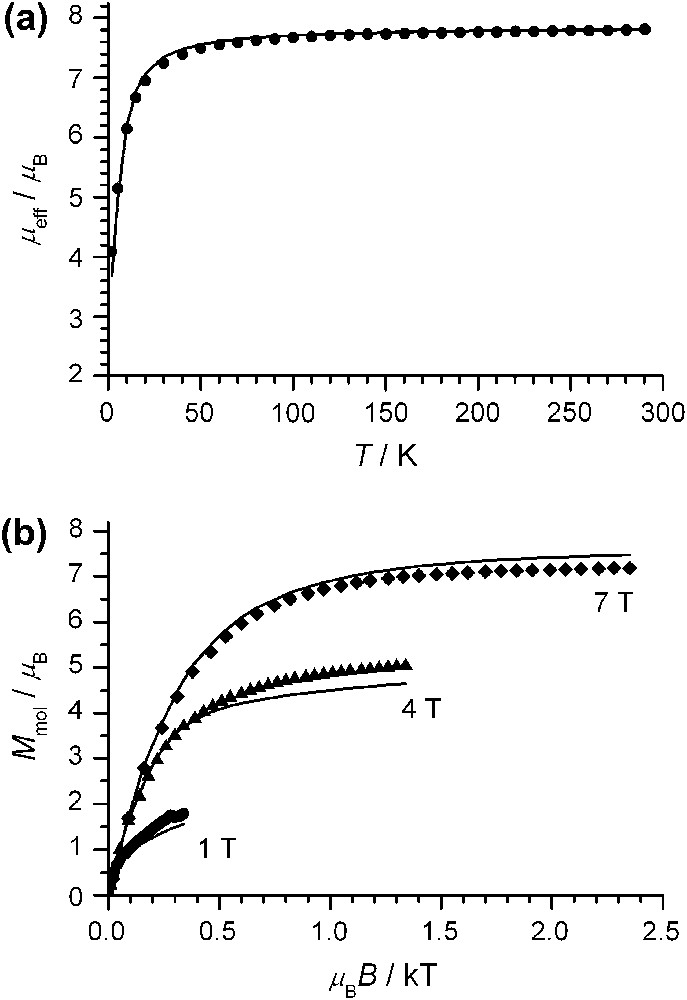

Magnetic susceptibility data of complex 1 were measured on a microcrystalline sample in the temperature range 2–290 K with an applied field of 1 T. In the temperature range 290–70 K, μeff exhibits only a slight decrease from 7.81 μB at 290 K to 7.59 μB at 70 K. Below 70 K, the decrease is more pronounced with a value of μeff = 4.09 μB at 2 K (Fig. 3a). This temperature-dependence of μeff can be interpreted by two extreme limits for a system of three h.s. MnIII ions with local spins of Si = 2: (a) a weak antiferromagnetic interaction and no zero-field splitting (isotropic limit) and (b) by strong zero-field splittings and no exchange interactions (uncoupled limit). However, all combinations in-between might be also possible.

(a) Temperature-dependence of the effective magnetic moment, μeff, of 1 at 1 T; (b) variable temperature–variable field magnetization measurements of 1 at 1 T, 4 T, and 7 T. The solid lines in (a) and (b) are simulations to the experimental data using the spin-Hamiltonian provided in the text with one common set of values: J = −0.30 cm−1, D = −4.0 cm−1, gi = 1.852, χTIP = 332 × 10−6 cm3 mol−1 (subtracted from theoretical and experimental data), and θ = −0.21 K.

We have analyzed the magnetic properties of 1 using the appropriate spin-Hamiltonian (1) for three coupled spins Si = 2 including the isotropic Heisenberg–Dirac–van Vleck (HDvV) exchange Hamiltonian, the single-ion zero-field splitting, and the single-ion Zeeman interaction.1

| (1) |

Using the isotropic limit without zero-field splitting, we obtained a value of J = −0.42 cm−1. This value did not provide a reasonable reproduction of the VTVH (variable temperature–variable field) magnetization data (Fig.3b), which are strongly sensitive to zero-field splitting effects. Analysis of the VTVH data indicated a significant zero-field splitting and an antiferromagnetic coupling of lower extent as obtained for the isotropic limit. Simulations of both experimental data sets provided reasonable values for complex 1: J = −0.30 ± 0.05 cm−1, D = −4.0 ± 0.4 cm−1, gi = 1.852, χTIP = 332 × 10−6 cm3 mol−1, and θ = −0.21 K.

4 Conclusions

We have successfully prepared and structurally characterized the first trinuclear MnIII triplesalen complex 1. While trinuclear MoV [8] and CuII [9,26] complexes bridged by phloroglucinol-derived ligands exhibit ferromagnetic interactions, the trinuclear MnIII complex 1 and the trinuclear MnIII subunits of MnIII6CrIII show small antiferromagnetic interactions. We are currently investigating the dependence of the spin-polarization mechanism on the dn electron configuration of the metal ions used in the phloroglucinol-bridged trinuclear complexes, on the folding angles, and on the nature of the terminal substituents.

On the other hand, this study allowed the evaluation of the zero-field splitting of the MnIII ions in the triplesalen environment. The value of D = −4.0 cm−1 proves the success of our concept to employ salen-like coordination environment to introduce pronounced magnetic anisotropies in phloroglucinol-bridged complexes. We are currently synthesizing other members of the family of heptanuclear complexes M6AMB as candidates for single-molecule magnets.

We are confident that 1 as the first trinuclear MnIII triplesalen complex represents a good starting point to investigate the cooperative action of three manganese–salen subunits in Jacobsen–Katsuki-type catalytic transformations. Especially, the steric requirements enforced by ligand folding in these large complexes and the opportunity to influence this ligand folding by variation of the terminal phenol substitutions let us hope that we will be able to tune enantioselectivity in chiral triplesalen complexes.

5 Supplementary material

The supplementary material contains an ORTEP plot of 1 and can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.crci.2006.09.009. Crystallographic data for the structural analysis of 1 have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, CCDC No. 286978. Copies of this information may be obtained free of charge from The Director, CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB21EZ, UK, (fax: +44 1223 336 033; email: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk or www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie, the BMBF, the Dr. Otto Röhm Gedächtnisstiftung, and the DFG (SFB 424). We thank Dr. E. Bill (MPI for Bioinorganic Chemistry) for magnetic measurements and valuable discussions.

1 The program package julX was used for spin-Hamiltonian simulations and fittings of the data by a full-matrix diagonalization approach (E. Bill, unpublished results).