1. Introduction

Date palm trees cultivation (Phoenix dactylifera L.) is an important agricultural activity in arid and semi-arid regions worldwide, including the Middle East and North Africa, India, and the USA [1, 2]. Nowadays, the global cultivated area dedicated to date palms exceeds 1.381 million hectares and the number of date palm trees is around 120 million [3]. Throughout the growth and fruit harvesting phases of these trees, various residues are generated, consisting primarily of fronds, trunks, and seeds [4, 5, 6]. Research by Fang et al. [5] indicates that each productive date palm tree generates approximately 50 kg of waste annually, resulting in an annual worldwide production of about 6 million tons of lignocellulosic residues. Presently, the majority of these wastes are either incinerated or disposed of in landfills [6].

Recent studies have explored the use of these abundant wastes in various applications, including energy recovery, animal feeding, extraction of bio-based materials, soil enrichment, and treatment of wastewater and gaseous effluents [1]. One recommended approach for valorizing these wastes involves their thermochemical treatment through the pyrolysis process. This method permits their complete conversion into: (i) biofuels, serving as a renewable energy source [7], and (ii) biochars, which can be utilized for agro-environmental applications such as soil amendments [1] or efficient adsorbents for various mineral and organic pollutants including heavy metals, ammonium, nitrates, dyes, and pharmaceuticals [8, 9, 10, 11, 12].

Simultaneously, huge amounts of phosphorus (P) are lost in urban and industrial wastewaters, with projections estimating this amount to reach 2.4 million tons (MT) by 2050 [13]. Together with nitrogen, P can contribute significantly to the degradation of water quality through the eutrophication process [14]. Hence, the recovery of P from discharged wastewaters and its subsequent reuse within a circular economy framework can help preserve the environment and mitigate the excessive depletion of phosphate reserves [15]. Various technologies have been explored for P recovery from effluents, including P precipitation as struvite, P storage through polyphosphates accumulation, and P adsorption onto tailored materials like biochars [16]. The latter method is particularly promising due to its simplicity, environmental friendliness, and high effectiveness under specific conditions [17].

The transformation of date palm wastes into biochars for P recovery from effluents, followed by their use in agriculture as an organic amendment, represents an outstanding approach that aligns with circular economy and sustainability principles [1]. However, pristine biochars typically exhibit limited adsorption capacity for oxyanions in general, and P in particular, mainly due to their negatively charged surface, low specific surface area, and microporosity [18]. Consequently, the synthesis of engineered biochars has been identified as a promising research avenue to enhance their physico-chemical properties and, subsequently, their P recovery efficiency. In this regard, the impregnation of raw biomasses with metal-rich wastes [17] or solutions rich in magnesium [19], calcium [20], aluminum [21], and iron [22] has been experimentally tested at the laboratory scale for the synthesis of efficient metal-biochar composites. Review papers on the topic have indicated that there has been no clear relationship between P recovery efficiency and the type of metal used for biochar modification [18, 23, 24]. Indeed, this process is simultaneously influenced by various factors, including the metal concentration, nature of the feedstock, pyrolysis conditions, and adsorption conditions, particularly pH and initial P concentration [23].

Additionally, impregnating biomasses with solutions containing salt mixtures, such as Mg/Al, Mg/Fe, Zn/Al, and Ca/Fe, enables the production of layered double hydroxides (LDH)-modified biochars, potentially enhancing P recovery efficiency [25]. For example, a research study carried out by Hadroug et al. [26] demonstrated that post-modifying poultry manure-derived biochar with Mg/Al instead of Al alone increased P recovery by a factor of 3.3. A comparable result was observed by Zheng et al. [27], where the P recovery efficiency of Mg/Al-modified biochar from wheat straw was 15.9 and 1.9 times higher than the same biochar when modified with Mg or Al, respectively. However, the efficiency of LDH-loaded biochars in P recovery depends not only on the nature of LDHs loaded onto the biochar surface [28] but also on the type of the feedstock and also the pyrolysis and adsorption conditions [23]. For instance, the P recovery capacity of Mg/Al-modified biochars was found to range from around 7 mg⋅g−1 for coffee ground waste at 500 °C [29] to over 153 mg⋅g−1 for wheat straw at 600 °C [27]. However, very few studies have explored the use of biochars derived from raw and/or modified date palm wastes for P recovery from aqueous solutions [11, 12]. Besides, to the best of our knowledge, the modification of biochars derived from date palm fronds with both single and mixed salts (i.e., Mg and Al) and their application for P recovery from aqueous solutions have not been previously investigated.

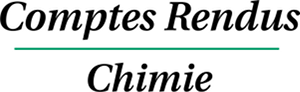

Therefore, the primary objectives of this research study are to: (i) synthesize and thoroughly characterize the three biochars generated from the pyrolysis of date palm fronds separately pre-impregnated with 1 M solutions of MgCl2, AlCl3, or MgCl2/AlCl3; (ii) investigate the efficiency of these three modified biochars in recovering P from aqueous solutions under different conditions such as contact time, initial pH, initial P concentration, and the presence of foreign anions; and (iii) deduce the benefits of using such P-loaded materials in agriculture.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Biochar synthesis

Dried date palm fronds (DPFs) were obtained from the agricultural experiment station of Sultan Qaboos University in Oman. Initially, they underwent a grinding step using a mechanical grinder, and only the fraction with particle sizes less than 1 mm was selected. Subsequently, the ground DPFs were mixed with solutions containing 1 M MgCl2, or 1 M AlCl3, or a mixture of 1 M MgCl2 and 1 M AlCl3. This impregnation process was performed using a magnetic stirrer (Gallenkamp, Leicestershire, UK) for a contact time of 16 hours and a mass-to-liquid ratio of 1:25 g⋅mL−1. This ratio was chosen in order to get a smooth agitation and consequently a good contact between the feedstock and the solution components. Following the impregnation step, the solid phases were separated through centrifugation at 3000 rpm (Beckman, Indianapolis, USA) and then dried overnight at 85 °C.

The pyrolysis procedure was identical to the methodology described in Jellali et al. [30]. In summary, the dried metal-loaded DPFs were heated under a nitrogen atmosphere using a tubular furnace (Carbolite, TF1-1200, Neuhausen, Germany). The pyrolysis temperature and heating gradient were fixed to 500 °C and 5 °C⋅min−1, respectively. The samples were maintained at this maximum temperature for 2 h before cooling to ambient temperature. The resulting solids were thoroughly washed with deionized water until getting stable electrical conductivity values corresponding to the elimination of excess metals and chloride ions. This step was followed by an overnight drying at 85 °C. Subsequently, to ensure experimental uniformity, these dried biochars were gently ground and sieved to obtain a particle size range of 0.08–0.5 mm. The resulting pre-modified biochars were designated as: DPF-Mg-B, DPF-Al-B, and DPF-Mg/Al-B, corresponding to treatments involving MgCl2, AlCl3, and a mixture of both salts, respectively.

2.2. Biochar characterization

The surface morphology and qualitative composition of the three metal-loaded biochars were analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) (Jeol, Jsm-7800F, Tokyo, Japan). X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained with a D8-advance diffractometer (Rigaku, Miniflex 600, Tokyo, Japan), covering diffraction angles (2𝜃) ranging from 10° to 90°. Identification of crystalline peaks on the biochars was carried out using the ICDD database (International Centre for Diffraction Data). The contents of major minerals (Mg, Al, Ca, K, P, etc.) were determined using an X-ray fluorescence (XRF) unit equipped with a rhodium target X-ray tube (Rigaku, Nexqc, Tokyo, Japan). Textural properties, including the Brunauer–Emett–Teller (BET) surface area, total pore volume, and average pore diameter, were derived from corresponding N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms at 77 K using a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 gas adsorption apparatus. Finally, the surface chemistry properties of the biochars involved the assessment of: (i) the pH of zero-point charge through the pH drift method, and (ii) the main functional groups through the exploitation of Fourier transform-infrared (FTIR) analyses spectra by a Miniflex 600 spectrometer (Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan). FTIR spectra were recorded from KBr pellets of the samples within the wavenumber range of 500 to 4000 cm−1.

2.3. Phosphorus recovery experiments

2.3.1. Preparation and analysis of P solutions

A phosphorus stock solution (3000 mg⋅L−1) was prepared by mixing the corresponding mass of Na2HPO4 (obtained from Sigma Aldrich) into deionized water. This stock solution was consistently utilized in this study for the preparation of the desired batch solutions at fixed P concentrations. Following the completion of the batch adsorption assays, the mixture underwent filtration through 0.45 μm filters (Whatman, Buckinghamshire, UK). Phosphorus concentrations in the filtered solutions were determined using the Fleury method and a UV–visible spectrometer (UV-1900i, Shimadzu; Kyoto, Japan) at a wavelength of 430 nm. The pH values of the aqueous solutions were adjusted using 0.1 M HNO3 and NaOH solutions. The pH measurements were conducted with a pre-calibrated pH meter (Mettler Toledo; Ohio, USA).

2.3.2. Batch adsorption procedure

Static adsorption experiments were conducted to assess the efficacy of the synthesized biochars in removing P from aqueous solutions under diverse experimental conditions. The procedure involved agitating a specific quantity of biochars in 50 mL of P solution at room temperature (20 ± 2 °C). The agitation was achieved using glass Erlenmeyer flasks and a multi-position magnetic stirrer (Gallenkamp, UK) set at a speed of 600 rpm. Default parameters, unless otherwise specified, included a biochar dose of 2 g⋅L−1, a natural pH (unadjusted), an initial P concentration of 100 mg⋅L−1, and a contact time of 180 min. These parameters were chosen on the basis of preliminary assays. The current study investigated the effect of the following parameters on P recovery by the synthesized biochars: (i) contact time varying from 1 min to 180 min, (ii) initial pH values between 3 and 11, (iii) initial P concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 mg⋅L−1, and (iv) the presence of competing anions such as chlorides, sulfates, and nitrates at concentrations of 1000, 400, and 100 mg⋅L−1, respectively. These concentrations are in the range of urban wastewater composition [31].

At a given time “t”, the amount of recovered P (qt) and the corresponding yield (𝜂t) were determined using the mass balance conservation principle as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

The experimental data on P recovery kinetics were fitted to three standard models: pseudo-first order (PFO), pseudo-second order (PSO), and intraparticle and film diffusion models. Additionally, the measured experimental isothermal data were fitted to the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R) isotherm models. These kinetic models equations and assumptions were previously presented in the literature [30, 32]. To assess the agreement between the measured kinetic or isothermal data (qmeas) and the calculated values (qcalc), the related correlation coefficients and mean average percentage errors (MAPE) were employed, as outlined below:

| (3) |

During this work, batch assays were realized in triplicate and the average values and standard deviation are presented in the corresponding figures.

2.4. Statistical analyses

The experimental data reported in this work represent the average values of triplicate measurements. Excel 2016 was used to perform the regression analysis and to plot the experimental data. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the measured data.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Biochars characterization

The process of modification had a significant impact on both the production yields and physico-chemical properties of the derived biochars as given in Table 1. Specifically, the biochar yields were 35.7%, 37.5%, 38.1%, and 37.7% for the raw DPFs, and DPFs pretreated with Mg, Al, and Mg/Al, respectively. This yield variation is attributed to the presence of metals on the surface of DPFs, which diminishes the efficiency of the carbonization process [33]. Some minerals, exhibiting a catalytic effect on the decomposition of cellulose into lower molecules that subsequently condense, contribute to the increased production yield of biochar [34]. A comparable pattern was observed for biochars derived from modified wheat straw [27] and a mixture of poultry manure and DPFs [35]. In this latter study, due to the relatively high Mg/Al contents deposited on the feedstock, the production yield of the corresponding biochar was 52.4% higher than the untreated one.

Main properties of the synthesized biochars (ND: not detected)

| Mineral composition (mg⋅g−1) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca | P | K | Mg | Al | Fe | S | |

| DPF-Mg-B | 5.2 | 0.9 | ND | 164.0 | ND | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| DPF-Al-B | 5.7 | 0.8 | 0.2 | ND | 160.0 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| DPF-Mg/Al-B | 3.7 | 0.4 | ND | 99.6 | 136.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Textural properties | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| BET surface area (m2⋅g−1) | Total pore volume (cm3⋅g−1) | Pore size (nm) | |

| DPF-Mg-B | 225.4 | 0.100 | 14.1 |

| DPF-Al-B | 130.8 | 0.124 | 7.4 |

| DPF-Mg/Al-B | 180.0 | 0.090 | 6.9 |

| Surface chemistry: pHzpc | |

|---|---|

| DPF-Mg-B | 11.00 |

| DPF-Al-B | 9.41 |

| DPF-Mg-Al-B | 5.58 |

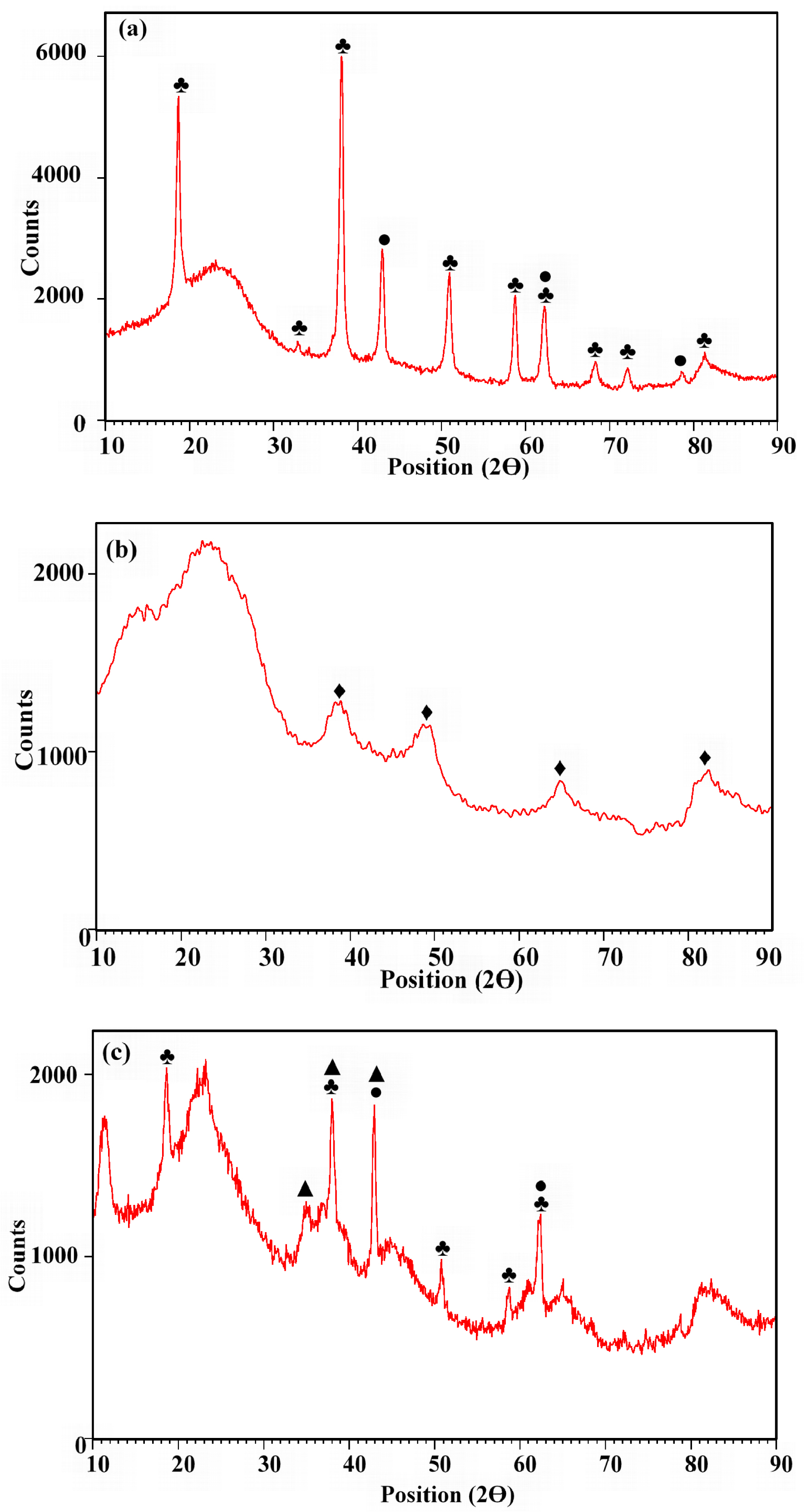

As anticipated, XRF analyses revealed elevated Mg, Al, and Mg/Al contents in the DPF-Mg-B, DPF-Al-B, and DPF-Mg/Al-B samples, respectively (Table 1). This increase can be imputed to the deposition of Mg- and/or Al-based nanoparticles on the surface of the biochars. A similar trend was reported for previous studies dealing with biochar modification with Mg and/or Al modified biochars [27, 36]. This result was supported by the XRD analysis (Figure 1). Indeed, the pre-modification of DPF with MgCl2 resulted in the appearance of nanoparticles of magnesium hydroxide (Mg(OH)2) and magnesium oxide (MgO) on the DFP-Mg-B (Figure 1a). These peaks were observed at diffraction angles (2𝜃) of 18.7°, 32.9°, 38.1°, 43.0°, 51.0°, 58.8°, 62.3°, 68.4°, 72.1°, 78.7°, and 81.3°. Similarly, on the DPF-Al-B surface, distinctive peaks corresponding to boehmite (AlOOH) were identified at 2𝜃 values of 38.5°, 48.9°, 64.9°, and 82.5° (Figure 1b). Lastly, various aluminum and magnesium nanoparticles were detected on the DPF-Mg/Al-B surface, including aluminum oxide (Al2O3), AlOOH, MgO, and Mg(OH)2 (Figure 1c).

X-ray diffractograms of DPF-Mg-B (a), DPF-Al-B (b), and DPF-Mg/Al-B (c) (♣: Magnesium hydroxide, ●: Magnesium oxide; ⧫: Boehmite; ▲: Aluminum oxide).

Previous studies by Lee et al. [37], Nardis et al. [38], and Hadroug et al. [26] have reported the deposition of Mg- or Al- or Mg/Al-nanoparticles on modified biochars when using MgCl2, AlCl3, and MgCl2/AlCl3 as modifier agents, respectively. It is noteworthy that the nature and loads of these nanoparticles depend largely on the conditions of the impregnation process. For instance, Zheng et al. [27] demonstrated the formation of magnesium aluminate (MgAl2O4) instead of Mg(OH)2. The pronounced abundance of Mg- and/or Al-nanoparticles on the surface of the current modified biochars may enhance the potential for P recovery through the precipitation process [39].

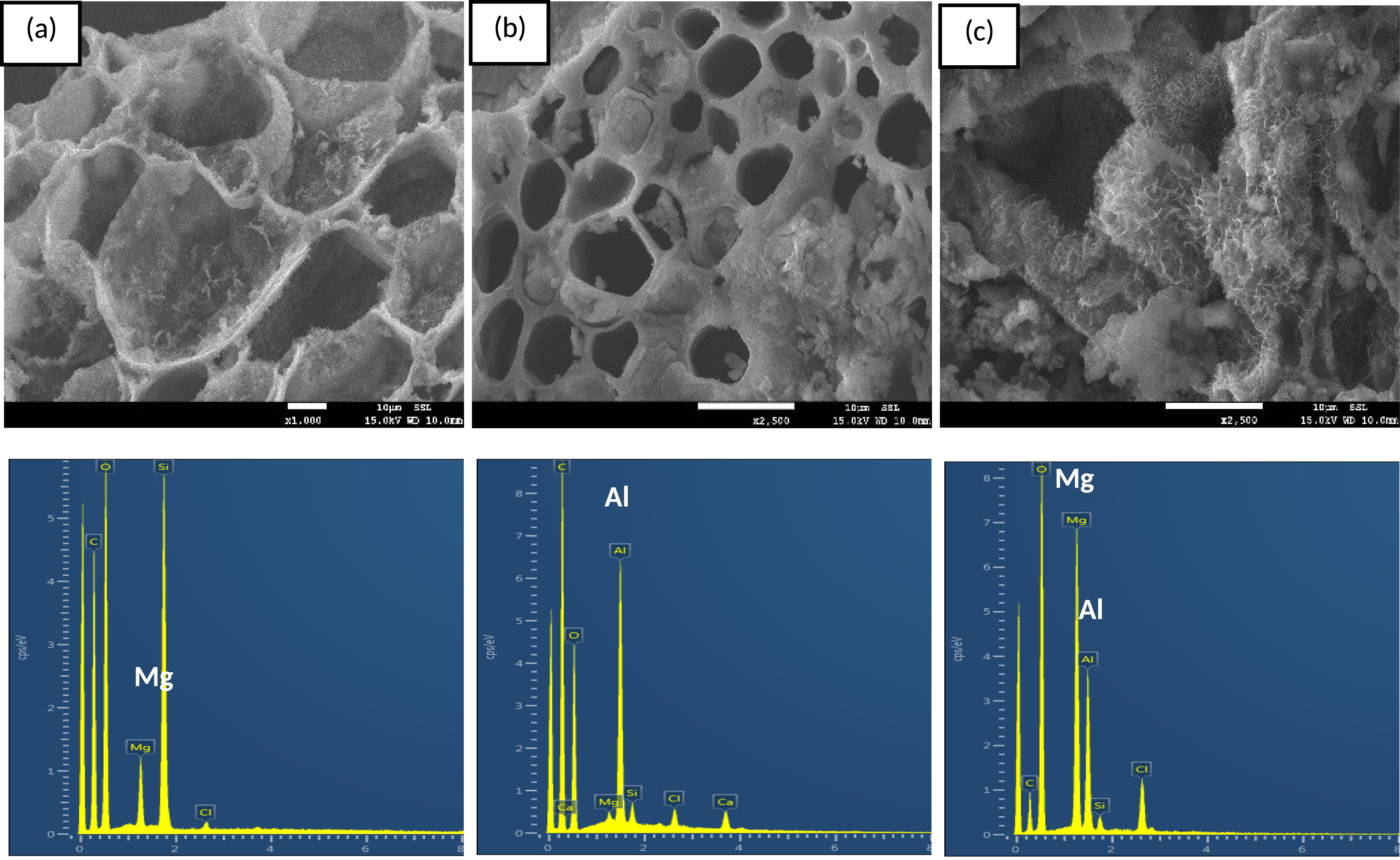

The presence of relatively high contents of Mg, Al, and Mg/Al peaks in the DPF-Mg-B, DPF-Al-B, and DPF-Mg/Al-B, respectively, was further corroborated through EDS analysis (Figure 2a–c). Moreover, SEM images revealed that the modified biochars showcased expanded micropores (Figure 2), a result of volatile matter release during the pyrolysis process [34].

SEM/EDS analyses of DPF-Mg-B (a), DPF-Al-B (b) and DPF-Mg/Al-B (c).

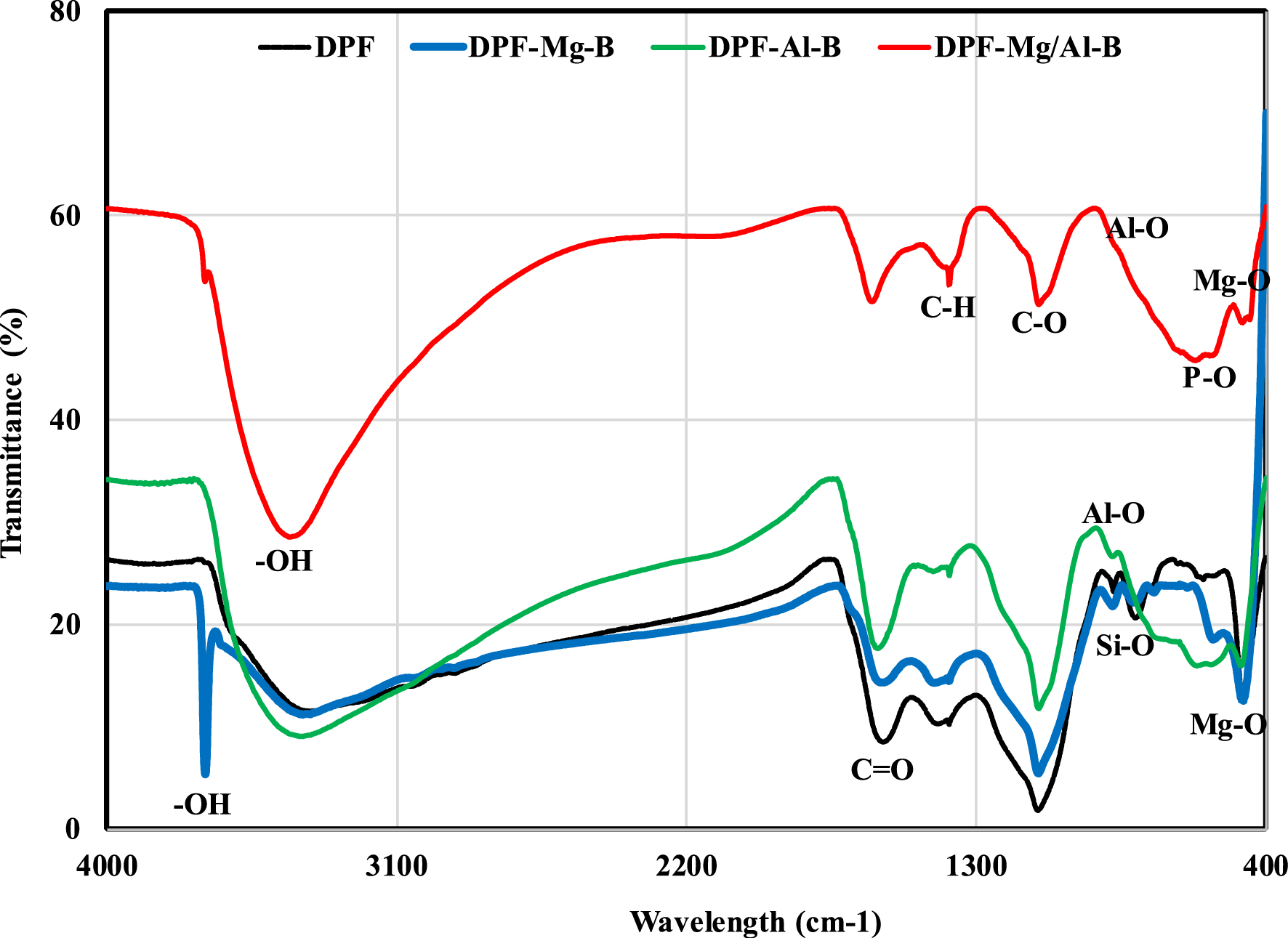

This outcome was validated with the N2 adsorption/desorption isotherm analyses, wherein the total pore volume (TPV) for DPF-Mg-B, DFP-Al-B, and DPF-Mg/Al-B materials was determined to be 0.100, 0.124, and 0.090 cm3⋅g−1, respectively (Table 1). It is noteworthy that the DPF-Mg-B exhibited the highest BET surface area value (225.4 m2⋅g−1), surpassing that of DPF-Mg/Al-B and DPF-Al-B by 1.3 and 1.7 times, respectively (Table 1). The comparatively lower surface area of DPF-Al-B could be attributed to pores blockage caused by the formation of Al-based nanoparticles. Specifically, the small size of AlOOH and Al2O3 facilitates their deposition into the pores, leading to blockage and consequently a reduction in the related BET surface area. This outcome is in line with previous research results [27, 38, 40]. For instance, Zheng et al. [27] showed that the pre-modification with AlCl3 reduced the BET surface area of a biochar generated from wheat straw pyrolysis by approximately 25.3%. Across all synthesized biochars, the average pore diameters remained relatively small, ranging from 6.9 to 14.1 nm (Table 1). The well-developed porosity and relatively high specific surface areas of the synthesized biochars may enhance the efficiency of P recovery from aqueous solutions. Concerning surface chemistry properties, the FTIR spectra of the raw DPF confirm the characteristic features of lignocellulosic materials, displaying a hydroxyl band (–OH) at 3391 cm−1, carbonyl (C=O) stretches associated with hemicellulose at 1589 cm−1, alkene group (C–H) bending vibrations at 1384 cm−1, and polar carboxylic (C–O) stretches linked to cellulose and lignin vibrations around 1109 cm−1 [41] (Figure 3). Additionally, a minor peak corresponding to the P–O group was identified at 567 cm−1 [17].

FTIR spectra of the raw DPF and its pre-modified biochars with Mg, Al and Mg/Al.

Following chemical impregnation, important alterations were evident in the FTIR spectra of the biochars. Notably, a new narrow peak emerged at 3695 cm−1, attributed to the –OH stretching vibration resulting from the formation of Mg(OH)2 nanoparticles [17]. Furthermore, the intensities of various peaks significantly increased (Figure 3). For instance, the –OH stretching vibration intensity in the spectra of the three modified biochars rose notably due to the formation of magnesium and aluminum nanoparticles. Additionally, the intensities of oxygen-based functional groups associated with aluminum oxides (i.e., C=O, C–O) have also increased as it can be seen in Figure 3. Inversely, the C–H peak nearly disappeared in the spectra of the three pre-modified biochars, confirming the successful doping of Mg and/or Al into the synthesized biochars. A similar result was found by Deng et al. [42] in their study on P recovery using Al-modified biochar generated from corn cob wastes.

Finally, the pre-modification of date palm fronds with Mg, Al, and Mg/Al led to the detection of new peaks that are associated with Mg–O at 475 cm−1 [43] and Al–O bands at 877 cm−1 [40], respectively.

The determination of the pHzpc for the modified biochars was conducted using the pH drift method. As expected, the highest value was observed for DPF-Mg-B (11.00), followed by DPF-Mg/Al (9.41) (Table 1). This can be attributed to the alkaline nature of Mg(OH)2 formed during the modification process. Similarly, elevated pH values were observed for a Mg-modified food waste biochar (11.03) [41], Mg/Al-modified date palm waste-derived biochar (10.02) [12], and Mg-modified pig manure-derived biochar (10.40) [38]. This outcome suggests that P recovery through electrostatic interactions will be advantageous across an expanded pH range (for aqueous pH values <pHzpc). Conversely, DPF-Al-B exhibited a relatively low pHzpc value (5.58), indicating that for common wastewater (typically with a pH higher than 6.5), P recovery through electrostatic interactions is likely to be minimal. Acidic pHzpc values were also reported for Al-modified pig manure-derived biochars [38].

3.2. Phosphorus recovery assays

The influence of key experimental parameters on P recovery using the three DPF-modified biochars was evaluated based on the conditions outlined in Section 2.3. The principal findings are elaborated upon in the following sections.

3.2.1. Effect of contact time: kinetic study

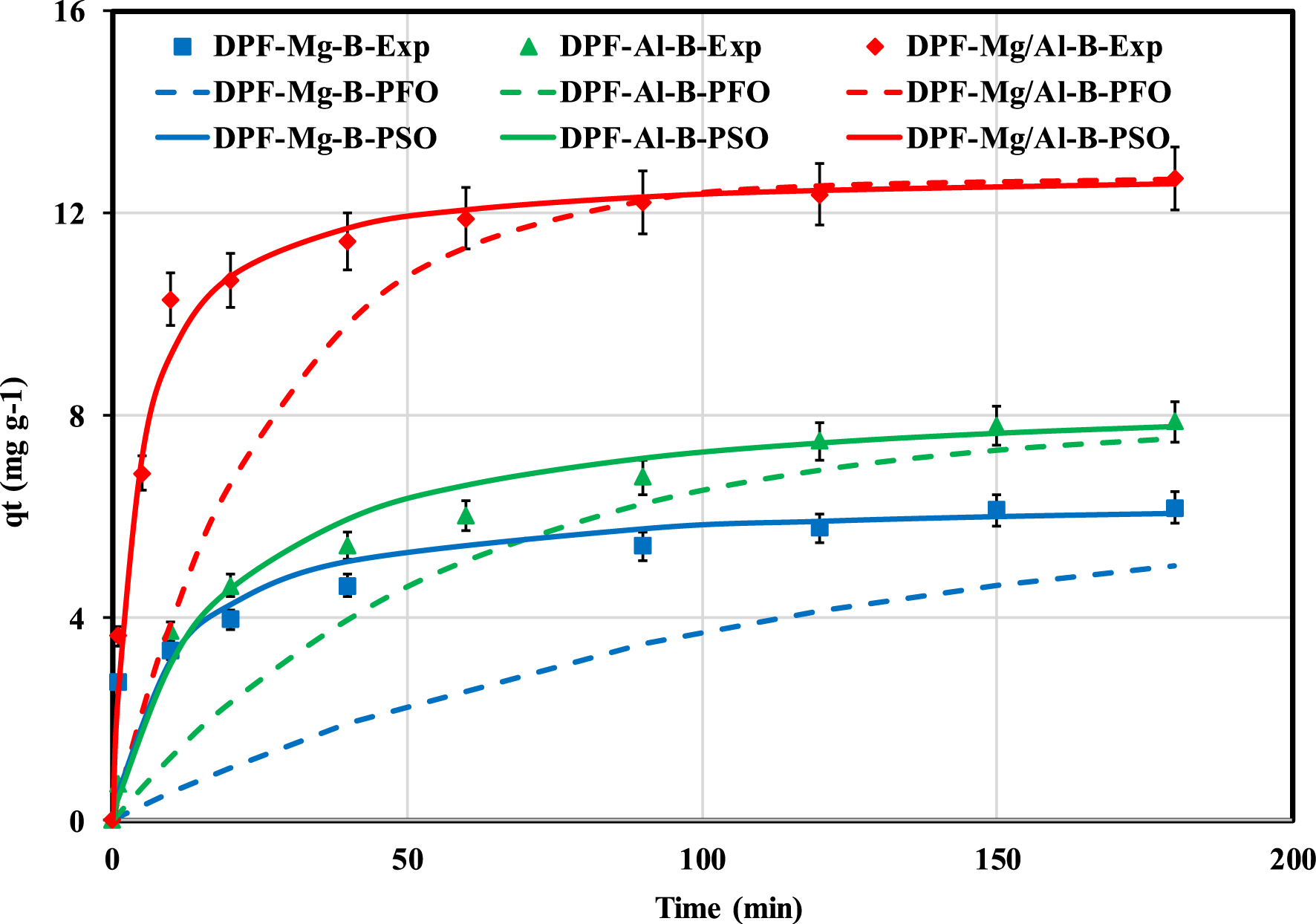

Figure 4 illustrates the correlation between the recovered P amounts and the contact time. It is evident that P recovery is contingent on time. Specifically, the rate of P adsorption experiences a substantial increase in the initial phase of the experiment (up to 10 min) before gradually diminishing and stabilizing at equilibrium after 3 h. At a contact time of 10 min, the recovered P rates by DPF-Mg-B, DPF-Al-B, and DPF-Mg/Al-B constituted 54%, 47%, and 81% of the total recovered amounts, respectively. The slower kinetic observed for DPF-Mg-B even if it has more interesting textural properties (see Table 1) may be imputed to the fact this biochar recovers P through a combination of physical and chemical mechanisms (i.e., complexation and precipitation). The relatively rapid P retention can be attributed to the facile transfer of this macroelement from aqueous solutions to the surface of biochar particles through electrostatic interactions [41]. Subsequently, the slower secondary kinetic phase can be ascribed to P ions transfer into the pores of the modified biochars through intraparticle diffusion [44]. Ultimately, an equilibrium state, characterized by quasi-constant adsorbed amounts, is achieved after around 2–3 h, signifying the net decrease of available adsorption sites [30]. A similar trend has already been observed for P recovery using various engineered biochars [12, 29, 41]. The required time to reach the equilibrium state is dependent on the biochar properties (i.e., number of active sites and accessibility easiness) and also the adsorption experimental conditions (i.e., initial concentration and agitation rate) [45].

Measured and predicted P recovery kinetic data by the Mg-, Al-, and Mg/Al-modified DPF-derived biochars.

It is noteworthy that the equilibrium time for the three synthesized biochars is shorter than those reported for Mg/Al-modified coffee ground wastes (12 h) [29], 20 h for calcium-rich biochar [35], and 24 h for Mg-modified corn straw-derived biochar [43]. Biochars with reduced equilibrium contact times are more appealing as they imply lower energy costs when scaling up the process to real-case applications.

The fitting of experimental data with kinetic models (Figure 4 and Table 2) reveals that the PSO model stands out as the most suitable. Across all three biochars, this model demonstrates the lowest MAPE and the highest correlation coefficients (R2). This outcome suggests that the primary driving force behind P recovery is likely chemical mechanisms such as electron exchange/sharing with functional groups on the biochar [43]. Additionally, the calculated rate constants (k2) were found to be 0.0156, 0.068, and 0.0198 for Mg-DPF-B, Al-DPF-B, and Mg/Al-DPF-B, respectively (Table 2). This implies that, due to a higher loading of Mg- and Al-based nanoparticles, Mg/Al-DPF-B exhibits the highest removal rate. Furthermore, for DPF-Mg-B and Al-DPF-B, the intraparticle diffusion coefficients are higher than the film diffusion coefficients. This indicates that the critical step for these two biochars is the diffusion of P through the boundary layer [26]. In contrast, intraparticle diffusion for Mg/Al-DPF-B appears to be the limiting step in P recovery. This is supported by the relatively high P amount adsorbed at the initial stages of the batch experiment (Figure 4). The DPF-Mg/Al-B exhibited the highest P removal capacity (12.7 mg⋅g−1) (Table 2). This aspect will be discussed later in the isotherm section.

Recovery kinetic parameters of P by the Mg-, Al-, and Mg/Al-modified DPF-derived biochars (T = 20 ± 2 °C, pH = 6.8, Dose = 2 g⋅L−1, C0 = 100 mg⋅L−1)

| Parameter | DPF-Mg-B | DPF-Al-B | DFP-Mg/Al-B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| qe,exp (mg⋅g−1) | 6.2 | 7.9 | 12.7 | |

| Pseudo first order model | k1 (min−1) | 0.0093 | 0.0176 | 0.0372 |

| R2 | 0.973 | 0.928 | 0.825 | |

| MAPE (%) | 52.5 | 29.4 | 30.7 | |

| Pseudo second order model | k2 (g⋅mg−1⋅min−1) | 0.0156 | 0.0068 | 0.0198 |

| qe,calc (mg⋅g−1) | 6.4 | 8.5 | 12.9 | |

| R2 | 0.869 | 0.978 | 0.980 | |

| MAPE (%) | 14.2 | 9.3 | 5.6 | |

| Film diffusion model | Df (×10−12 m2⋅s−1) | 0.19 | 1.24 | 3.4 |

| R2 | 0.981 | 0.975 | 0.990 | |

| Intraparticle diffusion model | Dip (×10−12 m2⋅s−1) | 1.72 | 1.83 | 1.3 |

| R2 | 0.871 | 0.930 | 0.990 |

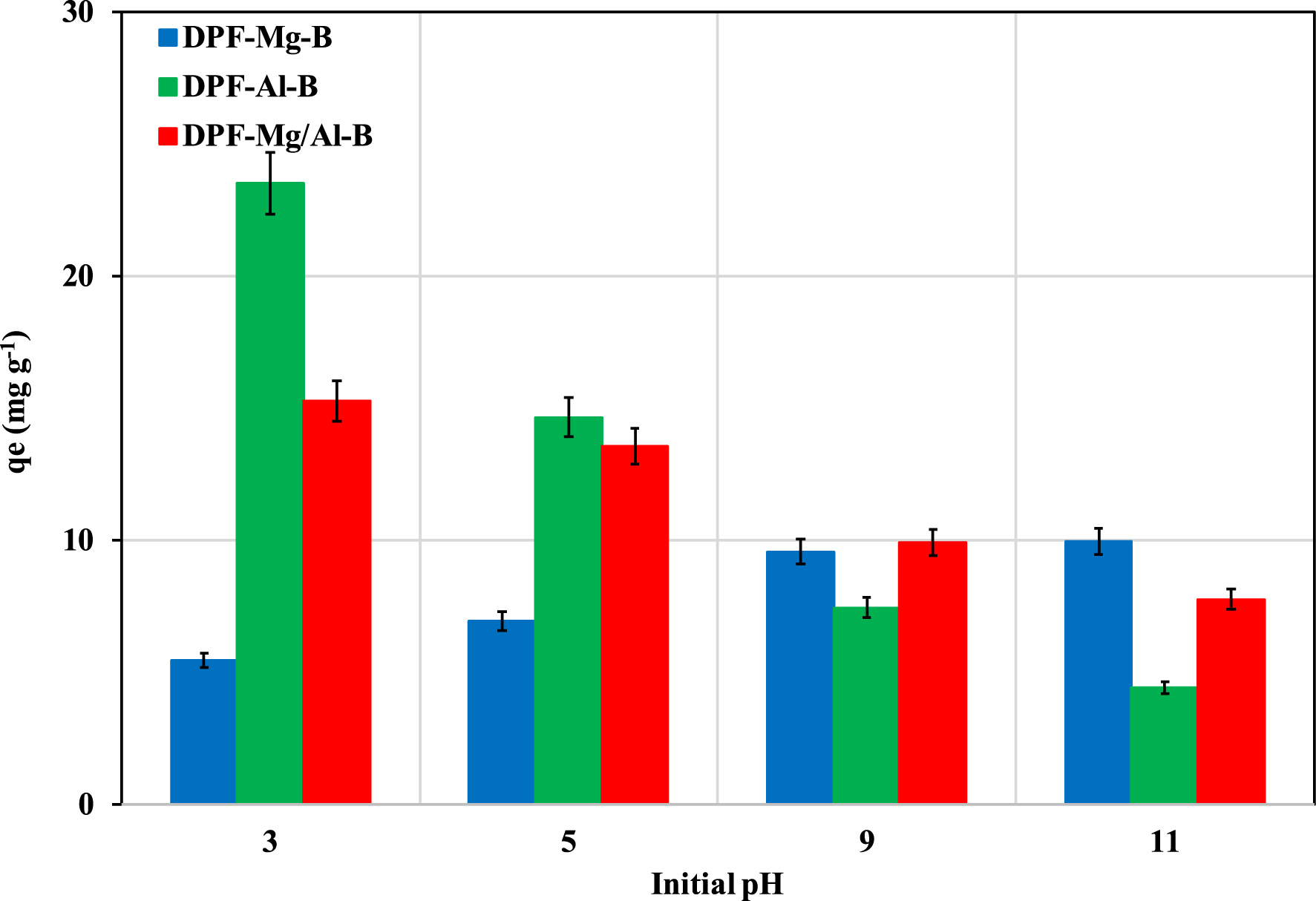

3.2.2. Impact of initial pH

The initial aqueous pH significantly influences the efficiency of P recovery by the three modified biochars (Figure 5). For Al-DPF-B and Mg/Al-DPF-B, the recovered P amounts decrease as the initial pH values increase. The highest values, at an initial pH of 3.0, were determined to be 23.5 and 15.3 mg⋅g−1 for Al-DPF-B and Mg/Al-DPF-B, respectively. This behavior was anticipated and is primarily attributed to the positive charge carried by these biochar particles at aqueous pH levels lower than their respective pHzpc values of 5.58, and 9.41, respectively. Within this pH range, aluminum oxides and magnesium oxides undergo protonation, forming ≡AlOH2+ and ≡MgOH+ species, consequently attracting P anions [26, 41]. On the contrary, for pH values higher than their pHzpc, the surfaces of Al-DPF-B and Mg/Al-DPF-B predominantly carry negative charges and negatively charged P compounds (mainly

Impact of initial pH values on P recovery by Mg-, Al-, and Mg/Al-modified DPF-derived biochars.

In contrast, DPF-Mg-B exhibited an opposing behavior. Despite having a high pHzpc (11.02), the recovered amounts of P increase with the rise of initial pH values (Figure 5). This result suggests the involvement of P complexation and probably precipitation mechanisms. In this context, different precipitates such as magnesium phosphates (Mg3(PO4)2) and/or di-magnesium phosphates (MgHPO4) may form and contribute to P recovery process [43, 46].

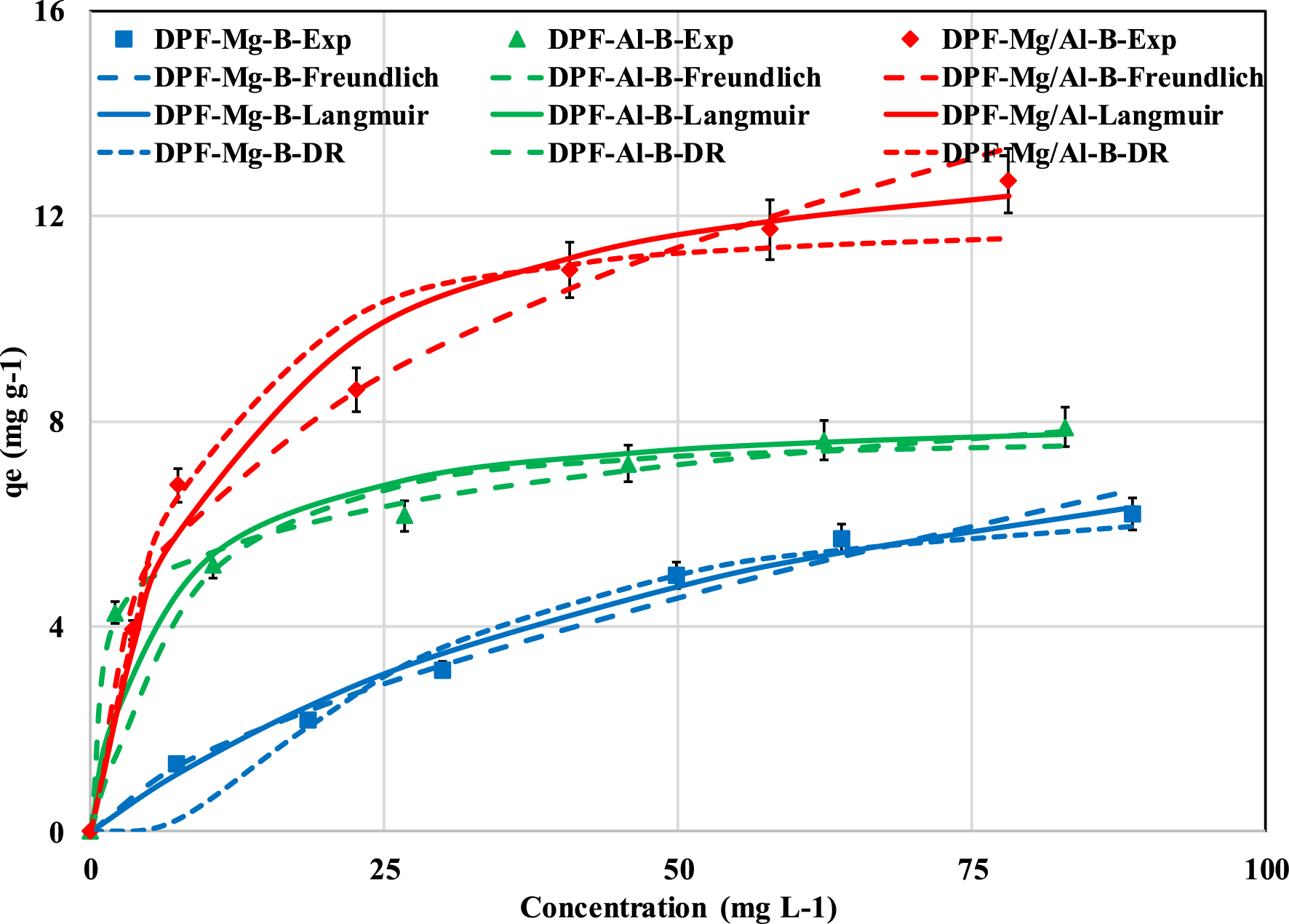

3.2.3. Effect of initial concentration: isotherm study

The recovered P amount increases with the rise in the initial aqueous concentration (Figure 6 and Table 3). Indeed, when the P aqueous concentration rises from 10 to 100 mg⋅L−1, the recovered amounts for DPF-Mg-B, DPF-Al-B, and DPF-Mg/Al-B increase by 4.8, 1.8, and 3.3 times, respectively (Figure 6). The prediction of the measured data with the Freundlich, Langmuir, D–R isotherm models showed that the former model was the most suitable. This model exhibits relatively high correlation coefficients and low MAPE (Table 3). Consequently, phosphorus recovery by these DPF-pre-modified biochars occurs heterogeneously and on multilayers on the modified biochars [47]. Furthermore, the P recovery process is favorable, given that the Freundlich constant “n” for all biochars falls within the range of 1–10.

Impact of the initial P concentration on its recover by the three DPF-modified biochars: observed and predicted data with Freundlich, Langmuir and D–R models.

Isotherm adsorption parameters for P recovery by the DPF pre-modified biochars (T = 20 ± 2 °C, t = 3 h, Dose = 2 g⋅L−1, pH = 6.8)

| Isotherm | Parameter | DPF-Mg-B | DFP-Mg/Al-B | DPF-Al-B |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | KL (L⋅mg−1) | 0.016 | 0.182 | 0.096 |

| qm,L (mg⋅g−1) | 10.8 | 8.3 | 14.1 | |

| R2 | 0.982 | 0.864 | 0.970 | |

| MAPE (%) | 8.3 | 11.2 | 6.7 | |

| Freundlich | n | 1.5 | 5.8 | 2.8 |

| KF | 0.341 | 3.636 | 2.843 | |

| R2 | 0.970 | 0.981 | 0.971 | |

| MAPE (%) | 6.3 | 3.0 | 6.8 | |

| D–R | qm,D-R (mg⋅g−1) | 6.6 | 7.7 | 11.8 |

| E (kJ⋅mol−1) | 1.6 | 3.7 | 3.7 | |

| R2 | 0.956 | 0.839 | 0.937 | |

| MAPE (%) | 18.3 | 14.5 | 6.0 |

Concerning the Dubinin–Radushkevich (D–R) model, the calculated free energy values for the three investigated biochars were below 8 kJ⋅mol−1 (Table 3), suggesting that the P adsorption may be governed by physical processes. This observation contradicts the results of the kinetic study, which indicates that P recovery involves mainly chemical mechanisms (see Section 3.2.1). Consequently, as proposed by Zhu et al. [43], P recovery by the modified biochars might entail a combination of both physical and chemical processes. It is noteworthy that DPF-Mg/Al-B emerges as a promising material since its efficiency is much higher than some pristine, and Fe- or La-modified biochars [48, 49, 50]. Moreover, its P recovery capacity (14.1 mg⋅g−1) is 7.8, and 2.3 times larger than biochars derived from the pyrolysis of Al-modified pine residues [21] and Mg/Al-modified almond shell [51] (Table 4). However, this capacity remains lower than that of various other biochars modified with Mg- and/or Ca-rich natural products such as sepiolite [42], powder marble wastes [17], and dolomite [52].

Comparison of DPF-derived biochars efficiency in P recovery with other Mg- and/or Al-modified biochars (qm,L: Langmuir’s adsorption capacity)

| Feedstock and provenance | Treatment conditions | Pyrolysis conditions | Adsorption conditions | qm,L (mg⋅g−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat straw, China | Impregnation with 0.5 M MgCl2 solution | T = 600 °C; G = 10 °C/min; t = 2 h | C0 = 10–2000 mg⋅L−1; D = 7 g⋅L−1; t = −h; T = − | 9.64 | [27] |

| Sugar cane straw, Brazil | Impregnation with 0.03 M MgCl2, 6H2O | T = 350 °C; G = 10 °C⋅min−1; t = −h | C0 = 0–1000 mg/L; D = 2 g/L; t = 24 h; T = − | 17.7 | [53] |

| Rice husk, Vietnam | Impregnation with 3.3 M MgCl2 for 2 h | T = 500 °C; G = − °C/min; t = 1 h | C0 = 10–100 mg/L; D = 1 g/L; pH = 8; t = 2 h; T = 25 °C | 17.1 | [19] |

| Tea waste, Turkey | Impregnation with Al (NO3)3 solution for 2 h | T = 300 °C; G = 3 °C/min; t = 3 h | C0 = 10–100 mg⋅L−1; D = 1 g⋅L−1; t = 24 h; T = − | 5.0 | [54] |

| Pine residues, South Korea | Impregnation with 0.71 M recovered aluminum solution from sludge for 24 h | T = 500 °C; G = 10 °C/min; t = 0.25 h | C0 = 12.5–400 mg⋅L−1; D = 2 g/L; pH = 7; t = 48 h; T = 25 °C | 11.9 | [21] |

| Impregnation with 0.71 M of AlCl3 solution for 24 h | 1.8 | ||||

| Impregnation with 0.71 M of Al2(SO4)3 solution for 24 h | 14.4 | ||||

| Almond shell derived biochar, China | Impregnation with 0.3 M MgCl2 and 0.1 M AlCl3 | - | C0 = −; D = 1 g/L; pH = 6.5; t = 12 h; T = 30 °C | 6.1 | [51] |

| Cattail biomass powder, China | Impregnation with 0.4 M MgCl2 and 0.2 M AlCl3 | T = 500 °C; G = −; t = 2 h | C0 = 5–80 mg/L; D = 0.5 g/L; pH = 7.2; t = 24 h; T = 25 °C | 35.2 | [28] |

| Rice straw, Japan | Impregnation with 0.03 M MgCl2 and 0.01 M AlCl3 | T = 475 °C; G = −; t = 2 h | C0 = 25–500 mg/L; D = 2 g/L; pH = 3.0; t = 24 h; T = − °C | 192.0 | [55] |

| Date Palm Fronds, Oman | Impregnation with 1 M MgCl2 | T = 500 °C; G = 5 °C/min; t = 2 h | C0 = 10–100 mg⋅L−1; D = 2 g⋅L−1; t = 180 min, T = 20 °C | 8.3 | This study |

| Impregnation with 1 M AlCl3 | 10.8 | ||||

| Impregnation with 1 M MgCl2 and AlCl3 | 14.1 |

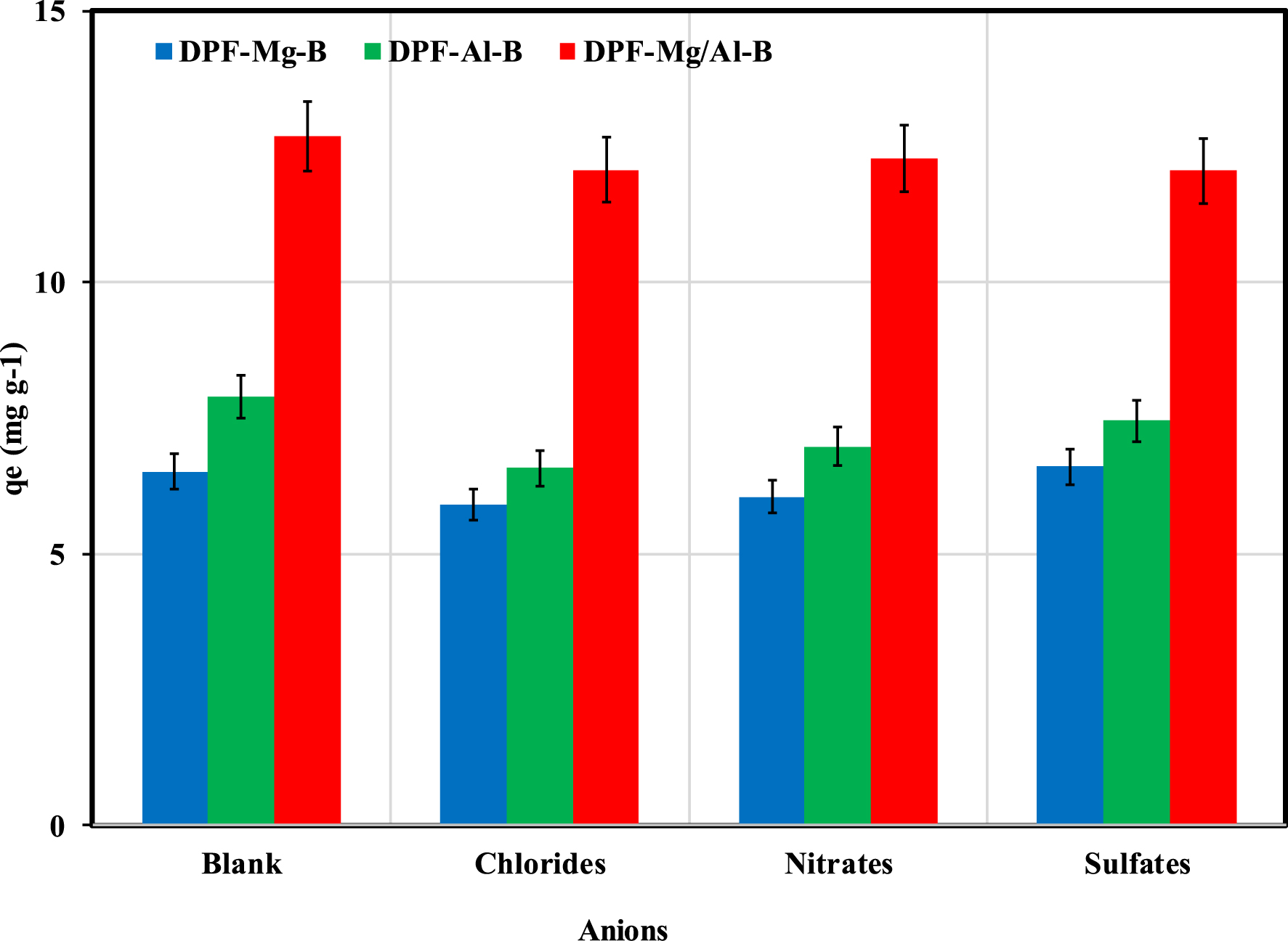

3.2.4. P recovery in presence of other anions

The influence of chloride, nitrate, and sulfate anions on P recovery by the three modified biochars is shown in Figure 7. The results indicate that, for all biochars, there was no discernible competition between P and sulfate ions. However, the co-presence of chlorides and nitrates resulted in a reduction of P adsorption for Mg-DPF-B and Al-DPF-B. The most pronounced effect was observed for Al-DPF-B, where the P adsorption capacity decreased by 16.6% and 11.5% in the presence of chlorides and nitrates, respectively (Figure 7). This outcome may be attributed to the higher electronegativity of chlorides compared to nitrates and sulfates ions [56]. It is worth noting that no significant competition with typical anions (i.e., Cl−,

Effect of foreign anions presence on P recovery by DPF-Mg-B, DPF-Al-B and DPF-Mg/Al-B.

3.3. Benefits and challenges of using the P-loaded biochars

The synthesized biochars (i.e., DPF-Mg/Al-B) offer a potential solution for recovering phosphorus (P) and other nutrients present in urban wastewaters for a further subsequent use in agriculture. For this reason, the regeneration of the P-loaded modified biochars was not studied in this work. The recovery process can be facilitated by using a dedicated continuous stirring tank reactor (CSTR) or laboratory column [17, 58]. These systems can be implemented in real wastewater treatment plants and serve as tertiary treatment. For the case of CSTR system, the separation of the nutrient-loaded biochars from treated wastewater can be achieved by using a specialized settling device at the downstream of this system [23]. However, it’s important to note that the efficiency of P recovery in CSTR or column mode is usually lower than that observed in batch conditions due to the lower hydraulic residence time [35, 59]. This removal efficiency decrease should be absolutely taken into consideration in real-case applications since they are typically performed under dynamic conditions. The up-scaling process can be performed according to the methodology suggested by Bian et al. [60]. The resulting P-loaded biochars (e.g., DPF-Mg/Al-B) can be utilized in agriculture as slow-release fertilizers, providing an environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic fertilizers [28]. This approach holds significant advantages, including sustainable management of large quantities of date palm wastes, environmental preservation against pollution (groundwater, surface water, and air), reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, promotion of the circular economy concept, and decreased expenses for farmers [61].

However, the synthesis and on-site application of nutrients-loaded biochars face numerous complex challenges [62], including:

- Technical considerations such as optimizing pyrolysis conditions, particularly heating temperature and residence time, ensuring efficient separation between loaded biochar and wastewater, and reducing the leaching of heavy metals (i.e., Al) from biochars into subsurface components (soil, groundwater, cultivated plants).

- Economic viability constraints requiring substantial efforts to reduce the cost of biochar production. Depending on feedstock nature and pyrolysis conditions, biochar production costs could exceed US$17 per kg [63]. Utilizing renewable energy sources and valorizing the generated biofuels (bio-oil and biogas) during the pyrolysis process for pyrolyzers self-functioning can significantly reduce these costs.

- Social acceptance challenges, that is mainly exacerbated by the negative perceptions among some farmers and consumers regarding the use of waste-derived materials in agriculture. Addressing this issue requires tailored dissemination and communication campaigns across various media channels to enhance awareness and understanding of biochar production and safe application.

- Policy hurdles, necessitating the implementation and fair enforcement of dedicated laws governing biochar production from organic wastes within a circular economy framework. Incentives aimed at encouraging farmers to transition from synthetic fertilizers to P-loaded biochars can boost these efforts. Additionally, fostering concrete and efficient coordination among key stakeholders, civil society actors, and policymakers is an essential step.

4. Conclusions

In this investigation, three pre-modified biochars derived from date palm fronds were produced using impregnation with MgCl2, AlCl3, and a mixture of MgCl2 and AlCl3 solutions. The results indicate that the biochars modified with Mg and Mg/Al exhibit noteworthy physico-chemical properties, enabling efficient P recovery from aqueous solutions under a broad range of experimental conditions. The respective P recovery capacities for these two biochars were determined to be 10.8 and 14.1 mg⋅g−1, which are higher than various raw and modified biochars reported in the literature. The phosphorus recovery process seems to include both physical and chemical mechanism. Utilizing these P-enriched biochars as slow-release fertilizers in agriculture aligns with the sustainability and circular economy principles. However, further investigations are essential to assess their impact on the physical, chemical, microbiological, and hydrodynamic characteristics of agricultural soils, as well as on plant growth and productivity.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Funding

The authors would like to thank Sultan Qaboos University and Qatar University for funding this research work in the joint projects CL/SQU-QU/CESR/23/01 and IRCC-2023-004, respectively.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0