1 Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are leading the digital revolution and are exclusively used in portable electronic devices. In addition, their usage is rapidly increasing for utility in electric vehicles. Overall, it is estimated that a demand of almost 100 Gigawatt hours (GWh) of LIBs is needed to cover the requirements for electric vehicles. In addition to that, they are also used to support the fluctuating green energy supply from renewable resources. Thus, LIBs constitute one of the most important factors of technology in the 21st century.

Typically, a LIB is constructed by connecting several lithium-ion (Li-ion) cells together in parallel, series, or using a combination of configurations to form a module that can be integrated to build a battery pack [1,2]. In turn, a Li-ion cell comprised a cathode, an anode, and an electrolyte [1]. The electrodes are segregated by means of a microporous polymer membrane that enables the exchange of Li ions when inhibiting electrons. The LIB operates through cycles of charging and discharging via a shuttle chair mechanism. Initially, the electrodes are linked to an external electrical source during charging and the cathode releases its electrons, which travel externally to the anode. Concurrently, the Li ions in the electrolyte move from the cathode to the anode internally. This mechanism allows the storage of electrochemical energy in the form of a difference in the chemical potential between the cathode and the anode. Throughout the discharging phase, the electrons travel back from the anode to the cathode via the external load, whereas Li ions travel from the anode to the cathode through the electrolyte.

The performance of LIBs depends on specific energy, specific capacity, cyclability, volumetric energy density, safety, robustness, and discharging–charging rate. Specific energy (Wh kg−1) represents the energy that can be stored and released per unit mass and is calculated as a product of the specific capacity (Ah kg−1) and operating voltage (V) [3]. The specific capacity, which represents the quantity of charge that can be stored per unit mass, is dependent upon the number of electrons evolved from the reactions and atomic mass of the electrode material [3]. Another parameter that could be used to estimate the performance abilities of LIBs is cyclability, which represents the reversibility of the Li-ion insertion. Furthermore, volumetric energy density (Wh L−1) is defined as the power consumption of 1 W for 1 h per 1 L.

Various types of electrolytes and electrode materials have been explored as putative candidates for the fabrication of LIBs. Traditionally, the negative electrode was fabricated from carbon, the positive electrode was manufactured from a metal oxide such as LiCoO2 or LiFePO4, whereas the electrolyte consisted of a Li salt in an organic solvent. Alternative electrolyte materials such as polymer gels and ceramic electrolytes have also been reported. New approaches to designing the cathodes have been applied and different anode materials (e.g., Fe3O4) have been used. The focus of this review is the negative electrode materials, namely Fe3O4.

2 Fe3O4 anodes

Fe3O4 anodes represent an exciting alternative to traditionally used carbon anodes. Fe3O4 is characterized by high theoretical specific capacity (926 mAh g−1), safety, superior conductivity, abundant supply, cost-effectiveness, and ecofriendliness. However, it suffers from the occurrence of large specific volume changes in the host matrices through different cycling phases, which can lead to pulverization of electrodes and rapid capacity decay. Another potential issue is the first cycle irreversibility that limits how LIBs can be manufactured, which had typically been performed in the discharged state. Ways to address these issues include changes in the manufacturing process of the anodes while also developing iron oxide–based nanostructures and iron oxide–based composites on conductive substrates. Specifically, to address these challenges, new manufacturing techniques and designs that have been used include electrospinning [4], liquid shear spinning, magnetic-spinning [5], and force spinning [6], in addition to sol–gel polymerization [7]. These methods result in structures that can be clustered into two groups: Fe3O4 nanostructures and Fe3O4 on conductive substrates or other stable metal oxides.

2.1 Production techniques for Fe3O4 anodes

In the following sections, two commonly used manufacturing techniques are described: electrospinning and sol–gel polymerization. After that, we will discuss different advancements in nanostructures and stable metal Fe3O4 combinations.

2.1.1 Electrospinning

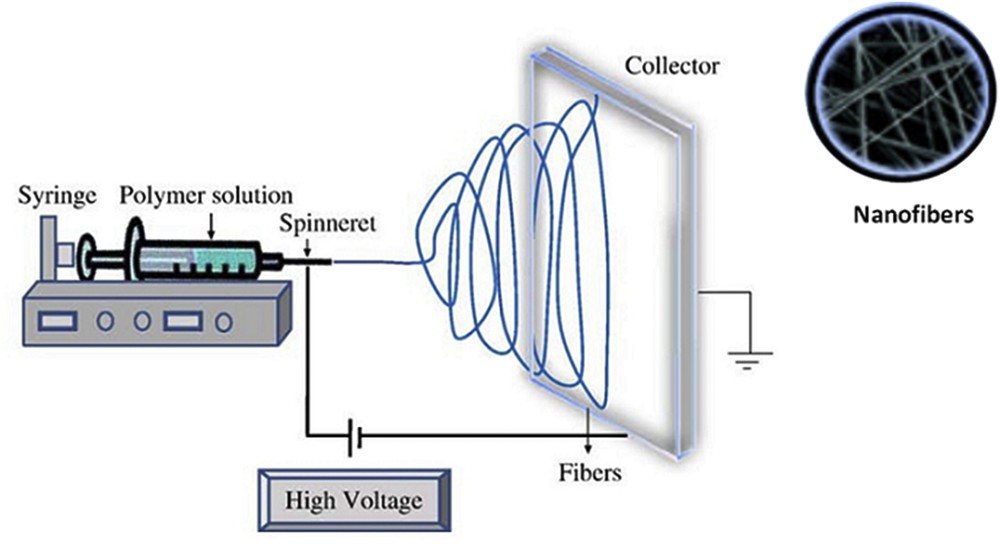

One of the widely used methods that have been used in preparing Fe3O4 composite fibers for LIB electrodes is electrospinning [8], which is a flexible technique used in the fabrication of a range of materials. Some research groups modified this method for the fabrication of nanoscale electrostatic fibers by subjecting a polymer solution or a melt to a strong electric field (Fig. 1) [9,10]. The fibers produced by this process possess diverse characteristics such as high surface area to volume ratio, controllable porosity, high reversible capacity, superior capacity retention, and acceptable rate capability.

A layout of the electrospinning workflow for the production of Fe3O4 electrodes for use in lithium batteries (adapted from Ref. [10]).

2.1.2 Sol–gel polymerization

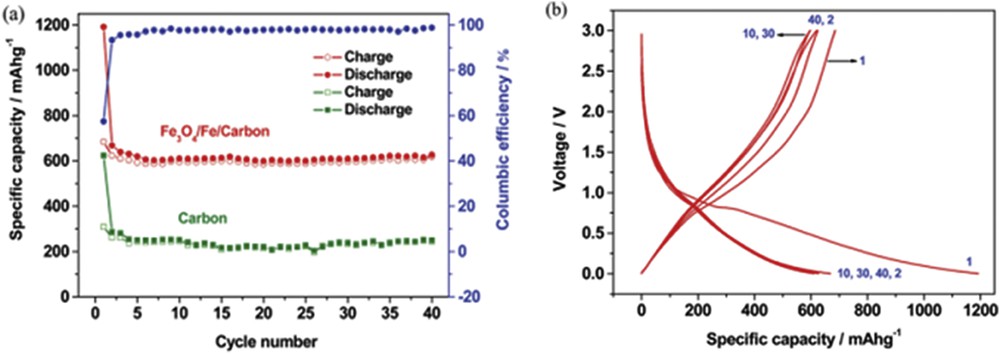

Sol–gel technique is used to synthesize inorganic polymeric materials, in which molecular precursors are first dissolved in a liquid and then hydrolyzed to yield solid-in-liquid dispersions (sols). Then, a condensation reaction forms the solid network filled with liquid (gel). Interestingly, Fe3O4/Fe/carbon composites were fabricated through sol–gel polymerization followed by heat treatment [7]. The composite was in the form of a core–shell construction where homogeneous spherical Fe3O4/Fe nanoparticles of 100 nm are wrapped by an amorphous carbon matrix. This carbon matrix accommodates any volume expansion/contraction of Fe3O4 that could take place during discharge–charge cycles and also preserves the electrodes. The composite electrode exhibited a stable and reversible capacity, albeit with a modest value (600 mAh g−1 at a current of 50 mA g−1 between 0.002 and 3.0 V) (Fig. 2a). It is worth noting that the Fe3O4/Fe/carbon composite electrode reduces the risk of high-surface-area Li plating at the end of recharge owing to its slightly higher voltage plateau (Fig. 2b).

(a) Cycling stability and (b) discharge–charge profiles of Fe3O4/Fe/carbon composite electrodes (adapted from Ref. [7]).

3 Fe3O4 nanostructures

3.1 Fabrication of Fe3O4 nanostructures

Nanostructure fabrication is one of the primary techniques to enhance the performance of the LIB electrodes. This approach has several advantages: (1) nanostructures possess short transport length that reduces the diffusion time of Li ions; (2) an increased electrode/electrolyte contact area that increases charge density; (3) strain can be significantly decreased during lithiation and dilithiation processes [11]; (4) protection of the structural integrity of the electrodes; and (5) maintain cycle performance. These advantages have led the way to various nanostructures (nanowires, nanotubes, nanowalls, nanosheets, and nanoparticles) being used to increase the effectiveness of Fe3O4 LIB electrodes [11,12]. Furthermore, to enhance the conductivities and decrease the diffusion length, Fe3O4 was integrated with a variety of metal nanostructures, polymers, and carbon materials.

3.1.1 Bicontinuous mesoporous Fe3O4 nanostructures grafted onto graphene foam

An interesting approach was reported by Luo et al. [11], where atomic layer deposition was performed to graft bicontinuous mesoporous Fe3O4 nanostructures on three-dimensional graphene foams (GFs). Atomic layer deposition has the ability to produce thin films for various types of materials with a high degree of conformity, thickness modulation, and film composition control [13]. The resulting composite (GF–Fe3O4) was directly used as a LIB anode and demonstrated high reversible capacity, rapid charging, and discharging capability. An elevated capacity of 785 mAh g−1 was attained at 1C discharge–charge rate and was maintained up to 500 cycles. Furthermore, the electrode sustained a capacity of 190 mAh g−1 at 60 °C, indicating its potential to be fully charged in 1 min.

3.1.2 Carbon-coated Fe3O4 tubular structures

A tube-shaped structure was fabricated from carbon-coated Fe3O4 by Han et al. [14] using a MoO3 nanorod as a hard template. Then, this template was removed and the structure was further modified with an optimized carbon nanocoating. The overall structure was not only hierarchical (built of smaller structural elements, which have their own structures) but also porous with a large surface area. The results of using this tabular structure as an anode for half of a Li-ion cell showed improved electronic conductivity, stable electrode–electrolyte interface, and a high degree of cycling performance with a specific capacity of 1020 mAh g−1 at 200 mA g−1 after 150 cycles. Furthermore, at a current density of 1000 mA g−1, a capacity of 840 mAh g−1 was maintained subsequent to 300 cycles without any capacity loss.

3.1.3 Uniform hierarchical Fe3O4 hollow spheres

Ma et al. [15] established a solvothermal approach to fabricate extremely uniform hierarchical Fe3O4 hollow spheres. The synthesis procedure was composed of two major steps (Fig. 3): (1) uniform hierarchical Fe-containing precursor hollow spheres were manufactured using a single-pot solvothermal method using Fe(NO3)3·6H2O, glycerol, isopropanol, and water; (2) the Fe-glycerate precursor was annealed in nitrogen to convert it to a highly crystalline structure. The discharge capacities of the hierarchical Fe3O4 hollow sphere electrode were 992, 853, 716, 548, and 457 mAh g−1 at current densities of 1, 2, 4, 8, and 10 A g−1.

The synthesis of the Fe-glycerate hollow sphere. (a) Deposition of Fe-glycerate nanosheets on the surface of the Fe-IPA solid spheres. (b) Growth of the nanosheets. (c) Formation of the hierarchical Fe-glycerate hollow sphere (adapted from Ref. [15]). IPA, isopropanol.

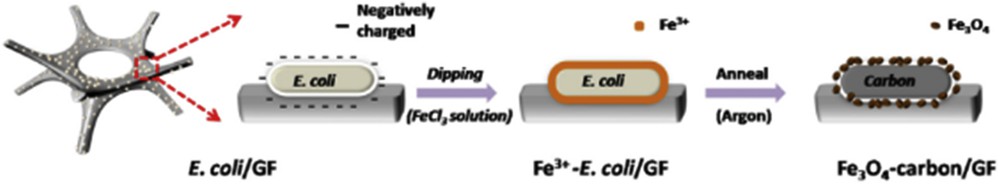

3.1.4 Bacteria inspired composites

A biologically inspired approach was reported in Ref. [16], where a micro-/nanostructured-Fe3O4-carbon/GF hybrid was used as a LIB anode. The synthetic process (Fig. 4) comprised culture of E scherichia coli on the GF, which was then treated with methanol to increase permeability. Next, the E. coli was subjected to a medium containing 0.1 M FeCl3, and finally, the mixture was annealed in argon. The resulting anode displayed a high reversible capacity of 1112 mAh g−1 at a current density of 100 mA g−1, even past 200 cycles.

Using E. coli in fabricating a Fe3O4-inspired anode [16].

4 Fe3O4 composites

4.1 Fabrication of Fe3O4 composites

4.1.1 One-dimensional hierarchical Fe3O4/carbon nanofiber nanocomposites

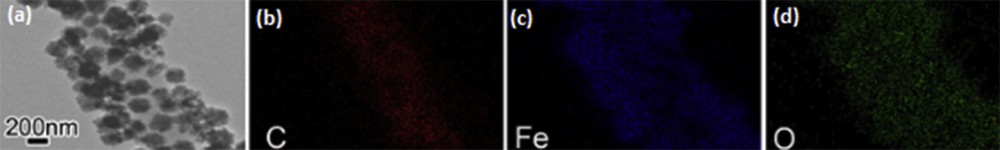

Jiang et al. used a solvothermal technique and thermal annealing to synthesize one-dimensional hierarchical Fe3O4/carbon nanofiber (CNF) nanocomposites (Fig. 5) [17]. This approach allowed integrating Fe3O4 nanoparticles with highly conductive CNFs, which act as a supportive matrix for dispersing Fe3O4 nanoparticles. This resulted in a greater surface area and exceptional electrical conductivities of the composite. Furthermore, this design allowed easy penetration of the electrolyte into the porous CNF network. This, in turn, led to the augmentation of the contact area between the electrolyte and active materials. It is worth noting that individual CNFs provided a rapid and efficient electron transfer pathway, consequently, the Fe3O4/CNF nanostructures displayed a reversible discharge capacity of 684 mAh g−1 after 55 cycles.

(a) Transmission electron microscope (TEM) image of Fe3O4/CNFs and corresponding mapping of (b) carbon, (c) iron, and (d) oxygen elements (adapted from Ref. [17]).

4.1.2 Fe3O4–graphene nanocomposites

Ultrafine Fe3O4 nanoparticles were uniformly anchored onto graphene substrates to construct Fe3O4–graphene nanocomposites through a hydrothermal process [18]. As an anode material for LIB, the nanocomposites displayed superior initial discharge and charge capacities of 1456 and 739.9 mAh g−1, respectively, at a high current density of 500 mA g−1. In addition, the charge capacity was maintained at 698.3 mAh g−1 after 200 cycles.

4.1.3 High capacity Fe3O4 nanorod/graphene composites

Another approach used Fe3O4 nanorod/graphene composites [19]. The synthesis process for these composites consisted of two steps: (1) FeOOH/graphene composites were first synthesized through uniform dispersion of FeOOH nanorods on graphene sheets, and (2) annealing in an argon atmosphere to form Fe3O4/graphene composites. One of the reasons for using graphene is to employ it as a reducing agent during the different phases of the composite manufacturing. The synthesized Fe3O4 nanorods were shown to have electrical contact with the graphene sheet, which also contributed to improving the overall electrochemical performance of the composite, with a reversible specific capacity of 1155 mAh g−1.

4.1.4 Three-dimensional Fe3O4 quantum dots/graphene aerogel materials

The particle sizes of quantum dots (QDs) are smaller than other nanomaterials in at least one dimension. They also possess an excellent cycling stability and demonstrate high capabilities in terms of electronic/ionic conductivity, specific surface area, and volume effect. They also show a lower number of defects in the crystal structure. QDs were used to manufacture a Fe3O4 QDs/graphene aerogel via a hydrothermal reaction followed by a heat treatment procedure [20]. The addition of graphene enhanced the electronic and mechanical properties of the aerogel. However, the resulting electrode displayed a high irreversible capacity loss, which was likely to be caused by the large electrochemical interfacial values resulting from Li+ storage.

4.1.5 Yolk and sac approach

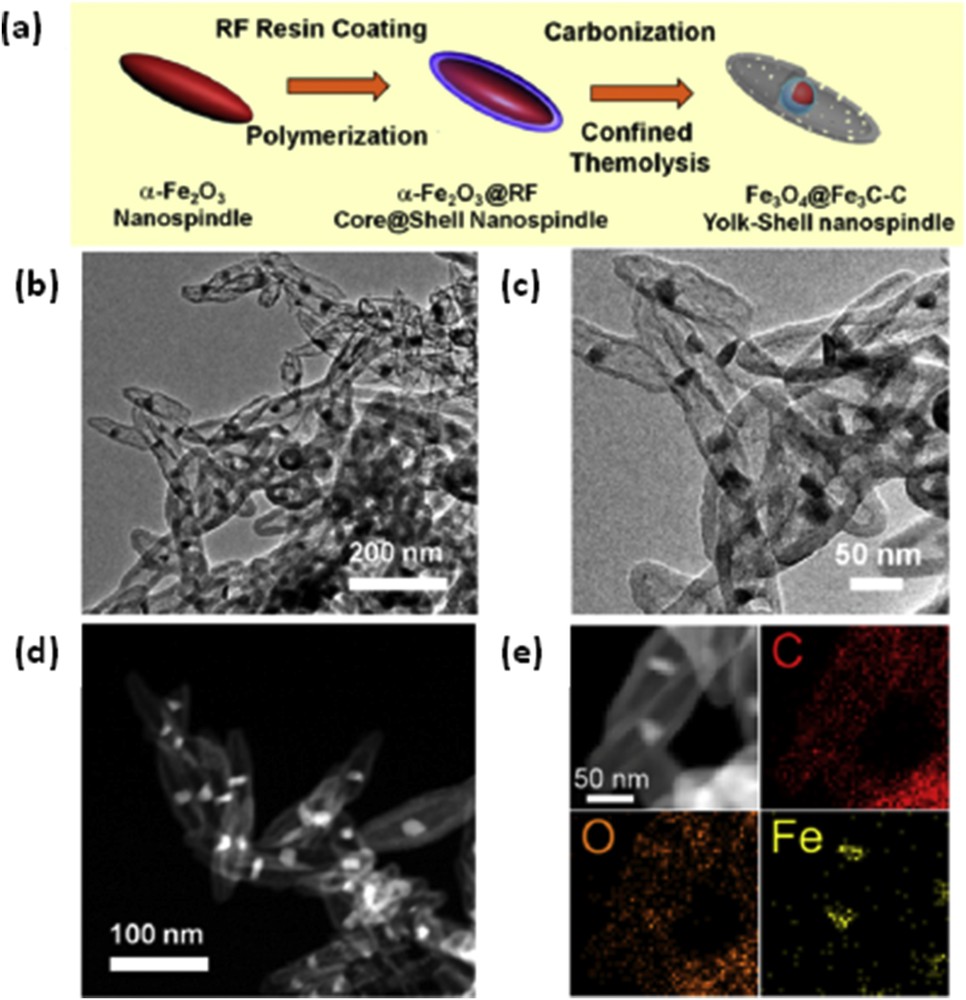

Zhang et al. [21] sandwiched a heterogeneous Fe3O4Fe3C core–shell nanoparticle inside a hollow carbon nanospindle to form a yolk–sac structure (Fig. 6). This design created an internal void space that could accommodate volume changes of Fe3O4. In addition, using the Fe3C shell restricted Fe3O4 dissolution. Overall, these added features enhanced the electrochemical characteristics of the composite, as evident from its reversible capacity (1128.3 mAh g−1 at 500 mA g−1), rate capacity (604.8 mAh g−1 at 2000 mA g−1), and cycling life (1120.2 mAh g−1 at 500 mA g−1for 100 cycles). The authors claimed that their design was the best Fe3O4-based anode material ever reported for LIBs.

(a) The fabrication of the Fe3O4@Fe3C–C yolk shell nanospindles. (b, c) TEM images, (d) Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image, and (e) TEM-Energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) mapping [21].

5 Stable Fe3O4-metal oxide combinations

Transition metal oxides possess higher electrochemical capacities than carbon anodes. However, they suffer from both low volume variation and inferior conductivity [22]. One strategy aimed to benefit from electrochemical capacity of high transition metal oxides by using their substrates as current collectors. These substrates were integrated with electrode materials via a coating procedure. Unfortunately, this approach did not show much potential as the substrates suffered from low flexibility, heavy weight, and not being environmentally friendly. To address these challenges, TiO2–α-Fe2O3 core–shell arrays were introduced. This configuration had multiple advantages, including large interfacial area, reduction of the diffusion pathways for electronic and ionic transport, induction of a positive synergistic effect, superior rate capability, large reversible capacity, and exceptional cycle performance. Therefore, this approach could represent an immense potential as an efficient anode material for Li storage. This idea was further extended in Taberna et al. [23], where an electrochemically assisted template growth of Cu-nanorods onto a current collector was followed by electrochemical plating of Fe3O4. A sixfold increase in power density over typical electrodes was observed, while conserving the overall discharge time. Furthermore, the capacity at the 8C rate was 80% of the total capacity after 100 cycles. However, a large hysteresis between charge and discharge was detected.

6 Fabrication technique comparisons

Many routes have been described to fabricate Fe3O4 anodes whether in fiber form, nanostructures, composites, or other forms. Each process has its advantages and disadvantages depending on the comparison and property that is being optimized. Table 1 highlights some of the positive and negative characteristics of each manufacturing technique.

Pros and cons of Fe3O4 fabrication methods.

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Electrospinning | High surface area to volume ratio, tunable porosity, superior capacity retention | Low tensile properties, poor durability |

| Sol–gel reaction | High voltage plateau, reduced lithium plating on electrode | Modest charge capacity, many step process |

| Graphene foam | Rapid charging and discharging, very good reproducibility, and consistency | Tedious manufacturing process |

| Carbon-coated tubular structures | Stable electrode–electrolyte interface, excellent cycling performance | Expensive, rare raw materials, different scale up |

| Hollow spheres | Excellent discharge capacities | Many step process |

| Bacteria inspired composites | Very good charge density and capacity | Not environmentally friendly |

| Fe3O4/CNF | Excellent electrical conductivity | Safety issues with carbon nanotubes |

| Fe3O4/graphene | Superior initial discharge and charge capacities | Expensive |

| Fe3O4 nanorod/graphene | Very high reversible specific capacity | Rare raw materials |

| Fe3O4 quantum dots/graphene aerogel | Excellent electronic and ionic conductivity | High irreversible capacity loss |

| Yolk–sac nanoparticles | Superior cycle life and reversible capacity | Tedious to create hollow carbon nanospindle, inconsistent nanoparticle size |

| Fe3O4 metal oxides | High electrochemical capacities | Low volume variation, inferior conductivity, inflexible, high density |

7 Applications of Fe3O4 microstructures in LIBs

Designing new Fe3O4 electrodes for LIBs could have a large impact in the future. Recently, the Li-air battery has gained momentum as it could deliver 5–10 times greater energy density as compared with classical LIBs. The theoretical specific energy density of a Li-air battery is 5200 Wh kg−1, whereas that of a LIB is only 150 Wh kg−1 [24]. Fe3O4 is a putative material for Li-air batteries owing to its oxygen reduction catalytic activity [25]. However, one of the challenges toward Fe3O4 deployment in Li-air batteries is the large volume changes and severe aggregation of the Fe3O4 particles that could take place during the charge–discharge cycling phases. In our research works, we reported novel pagoda-like Fe3O4 microstructures, which were produced by a microemulsion-mediated hydrothermal process, and then used as oxygen reduction catalysts in the air electrodes of lithium-air batteries [25]. This strategy has been shown to enhance the cell ability to have an initial discharge capacity of 1429 mAh g−1 at 1.5–4.5 V and 100 mA g−1. In another work, we prepared mace-like Fe3O4 nanostructures using a solvothermal method in cyclohexane/Triton X-100/n-amyl alcohol/water system [26]. The results of charge–discharge tests based on these nanostructures exhibited a high discharge capacity of 1427 mAh g−1 in ambient air. However, the battery still suffered from low cyclic performance, likely due to the accumulation of partially oxidized products. To address this issue, advanced analysis is being performed to quantify the reasons behind the poor cycling ability.

8 Conclusions

The application of Fe3O4 anode for Li batteries is gaining popularity. There are several approaches for the production of Fe3O4 anodes, such as electrospinning and sol–gel processes. There are also multiple strategies for Fe3O4 anode design, including using nanostructures with diverse morphologies (sphere, tube, and foam) and in combination with graphene or another metal. Among the currently available methods, the electrochemical properties of Fe3O4/carbon-based electrode materials seem to outperform other methods. However, much progress in electrochemical performance through rational design is still needed to revolutionize the automobile and energy industry.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51674262).