Version abrégée

1 Introduction

La sierra de Almagro se trouve dans la province d'Almeria (Sud-Est de l'Espagne) (Fig. 1A), dans la Zone interne bétique, formée, de bas en haut, par la superposition tectonique des Névado-Filabrides, Alpujarrides et Malaguides. La Zone externe est formée par le Prébétique et le Subbétique.

A. Location of the Sierra de Almagro within the Betic Cordillera. B. Simplified geologic map of the Sierra de Almagro. The position of the cross-sections of Fig. 3 is marked.

A. Situation de la Sierra de Almagro dans la cordillère Bétique. B. Carte géologique simplifiée de la sierra de Almagro. La position des coupes de la Fig. 3 est indiquée.

On a longtemps admis [7] que les terrains de la sierra de Almagro appartenaient à l'ensemble Alpujarride. Cependant, Simon [14,15] considéra qu'il s'agissait d'un ensemble particulier, qu'il nomma « Almagride ». Fut distingué ultérieurement [8], dans la même sierra de Almagro, un nouvel ensemble, appelé « Ballabona–Cucharón ». Par la suite [3,19], l'affirmation d'affinités des terrains « almagrides » avec des termes subbétiques amena à supposer [17] que le Complexe « almagride » correspondait à l'apparition en fenêtre de Subbétique, subduit sous la Zone interne. D'autres auteurs n'acceptèrent cependant pas l'existence des nouveaux ensembles (Almagride et Ballabona–Cucharón) et ramenèrent ces divers terrains dans le grand ensemble Alpujarride [1,6,11–13].

Le réexamen détaillé de la sierra de Almagro a permis d'en identifier les structures, de redéfinir ses unités tectoniques et de les situer du point de vue paléogéographique.

2 Unités distinguées dans la sierra de Almagro

De bas en haut, on distingue : (a) l'unité de Los Tres Pacos – nom d'une mine située à l'intérieur de la sierra de Almagro –, (b) l'unité de Variegato et (c) plusieurs petits affleurements du Complexe malaguide (Fig. 1B).

2.1 L'unité de Los Tres Pacos

Cette unité regroupe trois « unités » différenciées [8,14–21] au préalable, qui auraient été, de bas en haut, celles de Ballabona, Almagro et Cucharón, lesquelles étaient formées par une base détritique, localement avec d'abondants gypses, surmontée par des carbonates.

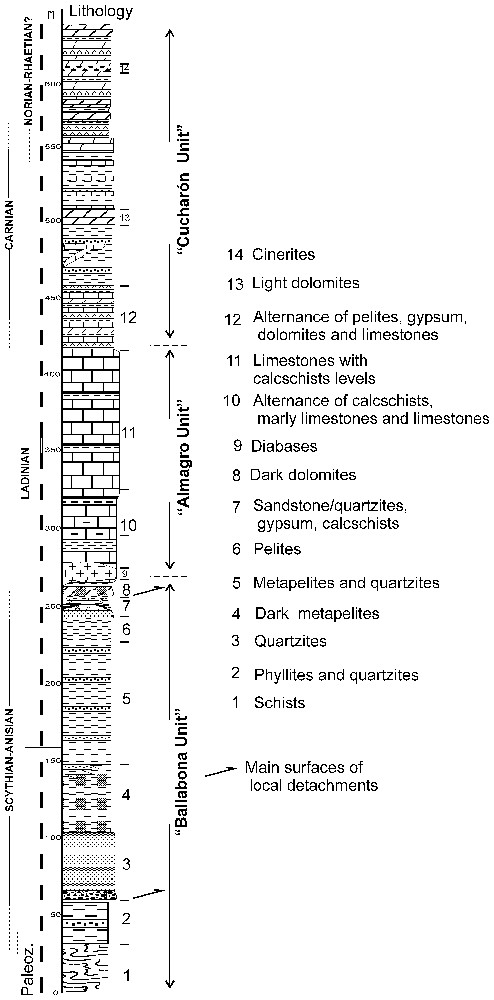

Elle débute en trois points par des schistes sombres, que l'on peut attribuer au Paléozoı̈que et qui sont surmontés par une série triasique constituée par deux formations (Fig. 2).

Stratigraphic series of the Tres Pacos unit. The approximate positions of the lithologic sequences of the supposed units of Ballabona, Almagro and Cucharón are marked.

Série stratigraphique de l'unité de Los Tres Pacos. Les positions approximatives des séquences lithologiques des prétendues unités de Ballabona, Almagro et Cucharón sont indiquées.

La formation inférieure, détritique, est constituée de quartzites, surtout vers la base, et de pélites schisteuses colorées ( « phyllites »). Au toit apparaissent des calcschistes et du gypse. Cette formation, d'une épaisseur d'environ 250 m, est attribuée au Trias inférieur. La formation supérieure, carbonatée, débute par des calcaires et par des marnes à intercalations pélitiques et des gypses, plus abondants vers le haut, avec de nombreuses intrusions de roches basiques. Elle se poursuit par des calcaires massifs et des dolomies. La formation carbonatée mesure, au maximum, environ 400 m et son âge va du Ladinien à un possible Norien.

2.2 L'unité de Variegato

Son appartenance alpujarride est unanimement acceptée. À la base apparaissent des schistes sombres attribués au Paléozoı̈que. Au-dessus affleurent des phyllites et des quartzites, rougeâtres au sommet, attribués au Trias inférieur ; l'épaisseur conservée est inférieure à 40 m. Plus haut affleurent des calcschistes et des calcaires et dolomies d'âge Trias moyen–supérieur, dont l'épaisseur conservée est de 100–150 m.

Il existe enfin, au sommet de la pile tectonique, quelques petits restes du Complexe malaguide : pélites et grauwackes paléozoı̈ques ; lutites, grès et conglomérats rouges du Trias. Ces roches sont parfois coincées entre des écailles de l'unité de Variegato.

3 Structure de la sierra de Almagro

Du fait de la distinction des diverses unités ( « Almagro », « Ballabona–Cucharón ») qui avaient été préalablement admises, nous avons soigneusement examiné leurs contacts.

3.1 Le contact entre Almagro et Cucharón

Il se placerait [14,15] entre des carbonates (unité « Almagro ») et au-dessus des gypses ( « Cucharón »). Cependant, la séparation des unités a été impossible sur tous les points observés, en raison de la totale continuité stratigraphique entre les deux termes.

3.2 Le contact entre Ballabona et Almagro

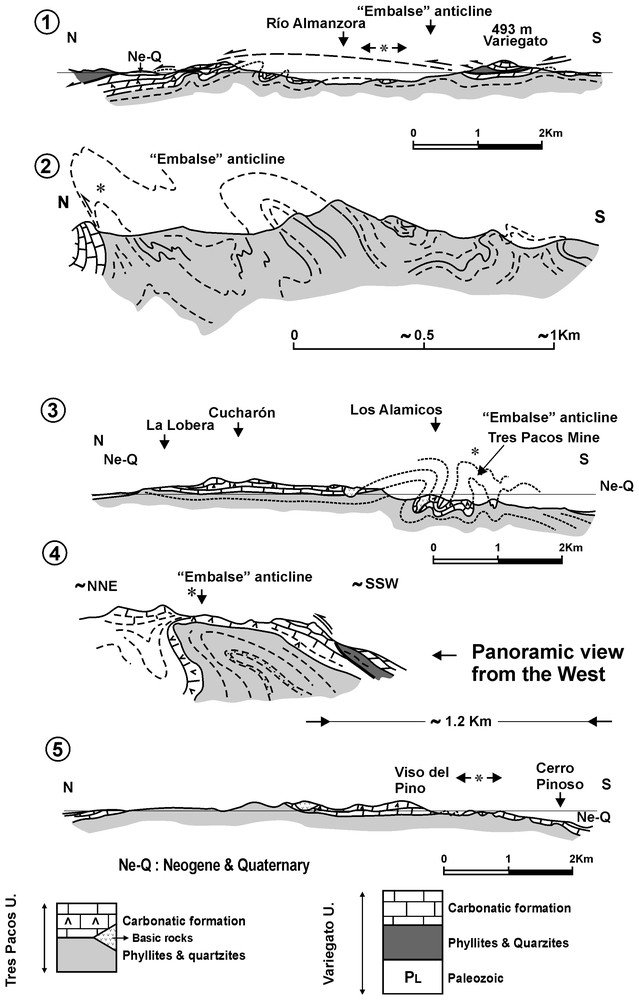

Dans l'ensemble, l' « unité de Ballabona » ( « phyllites et quartzites ») se trouve au-dessous de l' « unité d'Almagro » (carbonates), bien que localement, sur le flanc nord d'un anticlinal de direction est–ouest (passant par l' « embalse » – réservoir – sur le fleuve Almanzora), le contact soit renversé. Dans la partie occidentale de cet anticlinal, les carbonates d' « Almagro » sont situés sur les phyllites et les quartzites de « Ballabona » (coupe 1, Fig. 3). Plus à l'est, le contact entre ces matériaux devient vertical sur 5 km (coupes 2 et 3, Fig. 3), et il est même renversé localement, avec des angles d'environ 70° ; il se produit un décollement entre les deux termes. Plus à l'est, on observe la fermeture de l'anticlinal (coupe 4, Fig. 3), où les phyllites et les quartzites se trouvent en tous points sous les carbonates. Finalement l'anticlinal s'atténue et on observe la même disposition stratigraphique (coupe 5, Fig. 3).

Cross-sections showing the general structure of Sierra de Almagro and the relationships between the units of ‘Ballabona’, ‘Almagro’ and ‘Cucharón’. The asterisks mark the supposed contact between the ‘Ballabona’ and ‘Cucharón’ Units.

Coupes géologiques qui montrent la structure générale de la sierra de Almagro et leurs rapports entre les unités « Ballabona», « Almagro» et « Cucharón». Les astérisques indiquent la position du prétendu contact entre les unités « Ballabona» et « Cucharón».

Dans les secteurs central et nord de la sierra de Almagro, l'unité de Los Tres Pacos présente des plis importants, d'axes est–ouest (Figs. 1B et 3). Ces plis ont une vergence sud, opposée à celle de l'anticlinal de l' « embalse », dans la partie méridionale du massif.

En conclusion, les phyllites et les quartzites de « Ballabona » forment la base stratigraphique des carbonates d' « Almagro ». Ces termes ne peuvent pas former des unités indépendantes.

3.3 Position relative des unités de la sierra de Almagro

L'unité de Variegato, unanimement considérée comme Alpujarride, chevauche celle de Los Tres Pacos et présente à son tour plusieurs écailles [9], dont la plus haute est aussi la plus importante.

Enfin, les rapports entre l'unité de Los Tres Pacos et le Complexe névado-filabride peuvent être observés à l'ouest-nord-ouest de Cuevas del Almanzora (Fig. 1B). L'érosion dans la Rambla de Cicera permet de voir, au-dessous des sédiments du Néogène et du Quaternaire, que l'unité de Los Tres Pacos chevauche des matériaux (micaschistes et quartzites) névado-filabrides.

4 Conclusions. Conséquences paléogéographiques

1. Les unités supposées d'Almagro, Ballabona et Cucharón forment, en fait, un seul ensemble, d'âge Triasique, dans lequel « Ballabona » correspond à la formation inférieure ( « phyllites et quartzites ») de la série stratigraphique ; « Almagro » correspond à une partie de la formation inférieure et spécialement à la formation intermédiaire (carbonates, marnes, gypses) ; enfin, « Cucharón » correspond à la formation supérieure (carbonates, marnes, gypses).

2. On ne connaı̂t pas les Névado-Filabrides à l'intérieur de la sierra de Almagro, mais au sud de la sierra, elles affleurent clairement sous l'unité de Los Tres Pacos.

3. Il n'y a pas d'arguments pour maintenir l'hypothèse selon laquelle l'unité supposée d' « Almagro » soit d'appartenance subbétique. Notre unité de Los Tres Pacos, qui englobe en fait celle d' « Almagro », chevauche le Complexe névado-filabride et appartient, sans aucun doute, au Complexe alpujarride. On a considéré [17,20] que l'existence des gypses, très abondants dans le Trias du massif d'Almagro, était un caractère de la zone externe Subbétique, mais on sait aussi [6,13] qu'on en rencontre dans plusieurs unités alpujarrides. De même, l'existence de faciès calcaires de type « Muschelkalk » dans l'unité de Los Tres Pacos n'est pas exclusive du Subbétique. On les connaı̂t dans d'autres unités alpujarrides [11]. En conclusion, aussi bien dans la sierra de Almagro que dans les sierras qui l'environnent, il n'existe pas de Subbétique subduit, métamorphisé et affleurant en fenêtre tectonique.

4. L'unité supérieure de Variegato, divisée en plusieurs écailles et d'appartenance Alpujarride elle aussi, chevauche l'unité de Los Tres Pacos.

Nous pensons également qu'il n'y a aucun argument sérieux pour défendre l'existence d'un Complexe almagride (et d'un complexe Ballabona–Cucharón). Les termes qu'on leur a attribués [8,14–21] correspondent réellement à des unités tectoniques inférieures de l'ensemble Alpujarride.

1 Introduction

The Sierra de Almagro is situated in the eastern part of the province of Almerı́a, in SE Spain (Fig. 1A), in the Betic Internal Zone. This zone contains, from bottom to top, the Nevado-Filabride, Alpujarride and Malaguide complexes. The first two are affected by Alpine metamorphism. The External Zone is formed by the Prebetic, to the north, and the Subbetic, to the south, and is not metamorphic.

The whole Sierra de Almagro was considered as belonging to the Alpujarride Complex [7], but Simon [14,15], who distinguished five tectonic units (from bottom to top: Almagro, Ballabona, Cucharón, Variegato and the Betic of Malaga), claimed that the Almagro Unit was not originally in direct relation with the Alpujarride complex, and defined another one, the ‘Almagride Complex’.

The Almagro, Ballabona and Cucharón units were subsequently considered [8] as belonging partially to the Alpujarride Complex and partially to a new one, the Ballabona–Cucharón Complex. The general distribution of the units of this latter complex is shown in [16,18,20]. Other authors [21] distinguished the Ballabona and the Almagro–Cucharón units.

It has been indicated [3,10,19] that the Almagride has a great deal of stratigraphic affinity with the Subbetic, redefining the Almagride as characterised by a lithostratigraphic series affected by a low degree of metamorphism and with Subbetic affinities by many lithologic and palaeontological similarities. For this reason, the Almagride is considered in [17] to be part of the Subbetic subducted under the Internal Zone, metamorphosed and later exhumed, outcropping in tectonic windows under the Alpujarride Complex. This idea was followed up by some authors [2,4,5].

Other authors [1,6,11–13], however, have not accepted the existence of the Ballabona–Cucharón Complex or of the Almagride Complex, including the units in the Alpujarride Complex, as formerly [7] considered.

The existence or not of the Almagride Complex is an important question, because a positive conclusion would imply the existence of several metamorphic units of Subbetic origin, situated under the Nevado-Filabride Complex. The objectives of the present article are to identify the structures of Sierra de Almagro, to make a new definition of its units and to locate their palaeogeographic assignation.

2 Units distinguished in Sierra de Almagro and their main stratigraphic features

From bottom to top, we distinguish the following units: (a) The Tres Pacos unit – this name correspond to an old mine in the Sierra de Almagro –, (b) The Variegato unit, and (c) several small outcrops of the Malaguide Complex (Fig. 1B).

2.1 The Tres Pacos unit

This unit fundamentally constitutes the Sierra de Almagro and comprises three units, previously supposed to be differentiated: at the bottom, the Ballabona unit, above this, the Almagro Unit and, at the top, the Cucharón unit. The lithologic series of these units was formed by a detritic formation, locally with abundant gypsum, covered by a carbonatic formation.

At three points near the bottom, there are dark schists, probably dating from the Palaeozoic age. Above this, the Triassic series, generally detached at the base, presents two formations, the lower of which is detritic, while the upper is carbonatic (Fig. 2).

The detritic formation is divided into two parts; the lower one is mainly formed of white and beige quartzites, while the upper part comprises phyllites of various colours, especially dark blue. To the top, there are alternating levels of phyllites and quartzites, and the colours pass progressively to green and violet; finally, calcschists and gypsum appear. The formation is approximately 250 m thick and it is attributed to the Early Triassic.

The carbonatic formation begins with limestones and marlstones with abundant interbedded levels of pelites and gypsum. There are numerous intrusions of basic rocks, which formed iron mineralisations. At a higher position, the gypsum and the pelites (locally phyllites and even thin levels of quartzites) are more abundant, interbedded among limestones and dolomites. Towards the top, massive grey limestones and dolomites and also dark dolomites are predominant. The maximum thickness of this formation is approximately 400 m and its age ranges from the Ladinian to a possible Norian.

2.2 The Variegato unit

Dark schists, generally arranged in tectonic slides, from the Palaeozoic age, are observed at the bottom of this unit. Above these, there are bluish grey phyllites and quarztites, which are reddish towards the top. The conserved thickness is less than 40 m; they are attributed to the Early Triassic. Further up, a carbonatic formation is represented by calcschists at the bottom and yellowish to grey limestones layered in thin levels, passing to thicker, darker levels towards the top, and finally thick and even massive dark dolomites. The conserved thickness is about 100–150 m and the age is Middle–Late Triassic.

There are only small remains of the Malaguide Complex. There are some outcrops of pelites of grauwackes of Palaeozoic age and red lutites, sandstones and conglomerates of Triassic age, very schistosed, in a small outcrop situated between tectonic slides of the Variegato units, other outcrops with some remains of Mesozoic and Tertiary limestones exist in the northwestern part of the Sierra de Almagro.

3 Structure of the Sierra de Almagro

Due to the previous differentiation of units, it is necessary to review the contacts between the supposed units of Almagro and Cucharón, and between Ballabona and Almagro, now considered to be a single unit.

3.1 The contact between Almagro and Cucharón

At all points, separation is found to be impossible. Simon [14,15], in the central and northern part of Sierra de Almagro, attributed the phyllites and quartzites and the carbonates situated directly above to the Almagro Unit, while the interstratified gypsum, marls and carbonates and the higher carbonates were attributed to the Cucharón unit. Nevertheless, we do not find any reason to separate the two formations: we consider them to form part of a single stratigraphic series.

The relative abundance of gypsum, marls and carbonates in equivalent stratigraphic positions is not constant. In some points it is possible to separate carbonates in the bottom, above a thick formation with interbedded gypsum, marls and carbonates and, at the top, limestones and dolomites. But, at other points, especially the two lower parts, they cannot reasonably be separated.

In conclusion, we believe there is absolute stratigraphic continuity between Almagro and Cucharón, with the ‘Almagro Unit’ beneath the ‘Cucharón unit’.

3.2 The contact between Ballabona and Almagro

On the whole, the ‘Ballabona unit’ is situated under the ‘Almagro Unit’, although locally the contact is overturned on the north flank of an east–west anticline, situated in the area of the ‘embalse’ (reservoir) on the Almanzora River. This flank is generally vertical, and becomes normal or overturned, depending on the points. This anticline disappears laterally at each end.

At the western part of this anticline, the Almagro carbonates are above the Ballabona phyllites and quartzites (cross-section 1, Fig. 3). This is observable for a length of several kilometres. More to the east, the contact between the carbonates and the phyllites is vertical for a length of 5 km (cross-sections 2 and 3, Fig. 3). Locally, this contact is reversed, with angles of 70° or more. Between these two types of rocks, there is a tectonic detachment, but the higher levels of the phyllites and quartzites are always in contact with the carbonates, but not always with their lower levels. The general structure of phyllites and quartzites clearly traces the above-mentioned anticline.

Cross-section 4 (Fig. 3) shows the eastern end of the anticline. There is a clearly visible thick level of quartzites, which follows the northwards-facing anticline, as do the gypsum levels and the carbonates situated in a higher position. More to the east, where the anticline has disappeared, the phyllites and quartzites outcrop at many points under the carbonates (cross-section 5, Fig. 3).

In conclusion, the Ballabona phyllites and quartzites form the bottom of the Almagro carbonates, as can be seen at many points. Consequently, Ballabona and Almagro cannot be separated as independent units from and, obviously, the ‘Ballabona unit’ does not overthrust the ‘Almagro Unit’.

3.3 Structure of the whole Sierra de Almagro

In the central and northern sectors of Sierra de Almagro, our Tres Pacos unit presents several important southwards-facing folds, each one with an axis that is practically east–west, standing out in the northern sector a big anticline (Figs. 1B and 3), in which the southern limb of the eastern part is clearly reversed to the south. These folds face the south, in the opposite direction to the anticline situated in the ‘embalse’ area.

The Variegato unit overthrusts the Tres Pacos unit, and is situated on the southern and western borders of the sierra. It forms several tectonic thrust slides [9]. The higher one is by far the larger.

The relationships between the Tres Pacos unit and the Nevado-Filabride can be observed to the west-northwest of Cuevas del Almanzora, where erosion in the Rambla de Cicera riverbed enables us to see, under the Neogene and Quaternary sediments, that this unit overthrusts a Nevado-Filabride unit (formed by micaschists and quartzites).

4 Conclusions. Palaeogeographic consequences

1. The supposed units of Almagro, Ballabona and Cucharón [8,14–21] are in fact a single one, in which Ballabona corresponds to the lowest formation (phyllites and quartzites) of the stratigraphic series, Almagro, as was formerly defined, to a part of the lower formation and especially to the intermediate one (carbonates, marls, gypsum) and, finally, Cucharón to the highest one (carbonates, marls, gypsum).

2. The Nevado-Filabride complex outcrop to the south of the Sierra de Almagro, clearly under the Tres Pacos unit.

3. There is no evidence to support the hypothesis according to which the supposed Almagro Unit is of Subbetic dependence. The Tres Pacos unit, which in fact comprises this ‘Almagro Unit’, thrusts over the Nevado-Filabride Complex and doubtless belongs to the Alpujarride Complex. Moreover, the existence of gypsum, which is very abundant in this unit, is not exclusive to the Subbetic, but also exists in several Alpujarride units. Similarly, the existence of Muschelkalk facies in the Tres Pacos unit is not exclusive to the Subbetic, but exists in other Alpujarride units [11]. Consequently, neither in Sierra de Almagro nor in neighbouring sierras is there a Subbetic, subducted, metamorphosed and which later outcrops in a tectonic window.

4. The Variegato unit presents several tectonic slides and overthrusts the Tres Pacos unit.

As a final conclusion, we believe there is no basis to defend the existence of an Almagride Complex (or of a Ballabona–Cucharón Complex). The units attributed to these really correspond to lower Alpujarride units.

Acknowledgements

This article was financed by projects PB97-1267-C03-01 and PB97-1201 of the DGICYT and by groups RNM 0163 and 0217 of the Junta de Andalucı́a. A. Caballero redrew the figures.