Version abrégée

1 Introduction

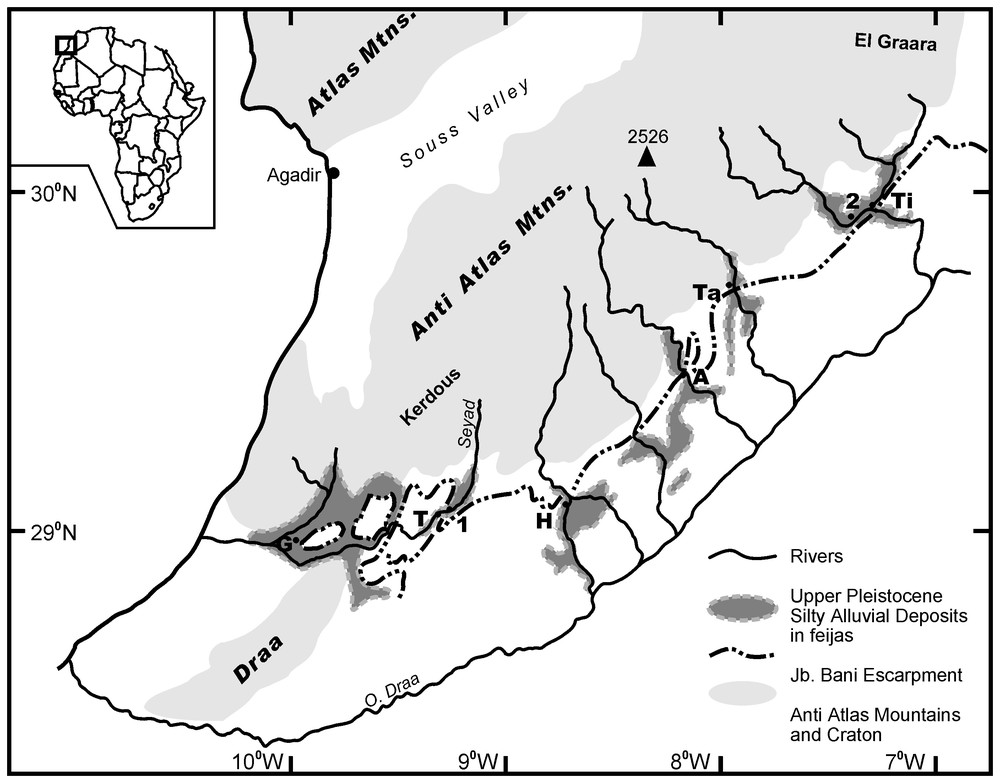

Les montagnes de l'Anti-Atlas, entre le massif du Kerdous à l'ouest et le massif El Graara à l'est, sont drainées vers le sud par les rivières Seyad, Tamanart, Aguemmamou, Akka, Tata, Myit, Tissint et Alougoum. Toutes ces rivières sont des affluents de la rive droite de l'oued Draa (Fig. 1). Là où ces rivières quittent leurs vallées encaissées dans les monts et plateaux du Précambrien métamorphique et dans les formations calcaires et schisteuses du fini-Protérozoı̈que et du Cambrien qui le recouvrent, elles traversent un paysage de plaines alluviales, de cônes, de glacis, de regs et de cuestas, développé dans l'Ordovicien–Dévonien plissé. Entre le front montagneux et le haut escarpement du Jebel Bani s'observe la première des vastes plaines alluviales, appelées « feijas ». Les rivières traversent le Jb. Bani dans des gorges ou « foums ».

Location map. G, Goulmine; T, Tarjijcht; Ta, Tata; A, Akka; Ti, Tissint; H, Foum el Hassan. 1, 2, 14C and OSL sample sites, respectively.

Carte de situation. G, Goulmine ; T, Tarjijcht ; Ta, Tata ; A, Akka ; Ti, Tissint ; H, Foum el Hassan. 1, 2, sites de prélèvement des échantillons, analysés respectivement par les méthodes 14C et OSL.

Ces feijas contiennent d'importants dépôts, sur 30–380 km2, de limons finement sableux de 5 à 30 m d'épaisseur, qui sont couramment disséqués par les rivières transportant des graviers en topographies de badland et de vastes terrasses à sommet plat. À la bordure des feijas, les limons débordent et enterrent les cônes et éventails alluviaux, ainsi que les glacis des pentes de colline adjacentes. La trace des limons peut être retrouvée dans les montagnes sous forme de terrasses, qui contrastent nettement par leur texture fine, des lits de cailloux des rivières actuelles, et des regs, éboulis ou roches nues de montagne. Les formations limoneuses se poursuivent au travers des foums du Jb. Bani et forment de vastes plaines sédimentaires, telles que celles au sud de Tata, Akka et Foum el Hassan, qui se développent à l'aval de l'oued Draa.

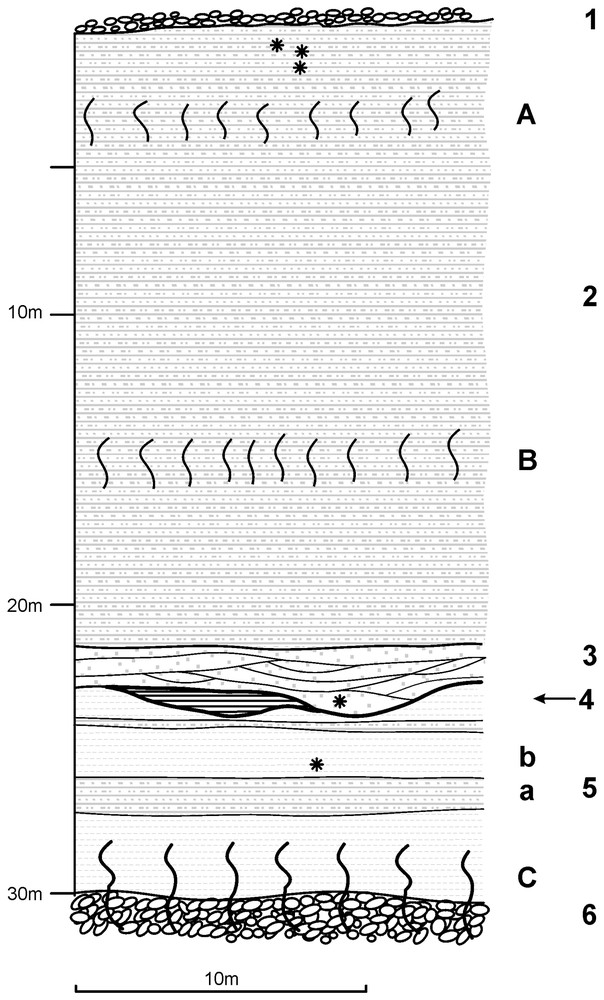

Comme le montre la Fig. 2, la plupart des coupes effectuées dans les formations limoneuses comportent trois membres : un membre basal limoneux, un membre de chenal graveleux inter-limon et un membre sommital limoneux. Les formations limoneuses reposent de manière abrupte sur d'épais conglomérats de cailloux bien arrondis, cimentés en une calcrète massive ; la cimentation gagne sur plusieurs mètres les limons susjacents.

Simplified section from the Northwest of Agadir Tissint. 1, Surface alluvial gravel sheet; 2, upper silt member; 3, intersilt channel member; 4, evaporite facies; 5, lower silt member; a, thinly bedded sandy silts; b, CaCO3-enriched clays; 6, calcreted alluvial conglomerate. A, B, Slightly indurated CaCO3 enriched zones; C, calcreted silty clays and conglomerate; ∗, stratigraphic position of OSL and 14C samples.

Coupe simplifiée du Nord-Ouest d'Agadir Tissint. 1, niveau alluvial superficiel à graviers ; 2, membre limoneux supérieur ; 3, membre de chenal inter-limon ; 4, faciès évaporitique ; 5, membre limoneux inférieur : a, limons sableux en lits minces ; b, argiles enrichies en CaCO3 ; 6, conglomérat alluvial encroûté. A, B = Zones légèrement indurées en CaCO3 ; C, argiles silteuses et conglomérat calcrétisés ; ∗, position stratigraphique des échantillons datés C et OSL.

Les surfaces des terrasses limoneuses sont fréquemment recouvertes par de fins niveaux de cailloux et galets arrondis, marquant le retour à des systèmes fluviatiles transportant des graviers, et par des clastes anguleux près des pentes de glacis, marquant une réactivation des processus de pente.

Les formations alluviales sablo-limoneuses et limoneuses sont le résultat de conditions climatiques et géomorphologiques très différentes de celles qui les précèdent ou qui les suivent durant l'Holocène. Elles se sont déposées pendant des périodes prolongées de vastes inondations et de flux de basse énergie, à forte concentration de sédiments en suspension. Les sédiments étaient issus d'épais manteaux d'altération, de colluvions de pente riches en matrice, dans les montagnes, et de chutes de poussières et de lœss, dont les sources sont encore à déterminer. Le membre graveleux inter-limon indique un retour à des débits fluviaux de haute énergie et à de fréquents événements d'érosion de pente.

Peu de travaux, excepté ceux de Dijon [4] et d'Andres [2], ont été publiés sur ces vastes formations limoneuses de l'Anti-Atlas du Sud marocain. Leur stratigraphie n'est pas très différente de celle des sédiments alluviaux soltaniens connus ailleurs au Maroc, qui ont été résumés et datés par Delibrias [3], Rognon [6] et Weisrock [8]. Cependant, Andres [2] fait état d'une seule détermination d'âge 14C de ans BP conv., obtenue à partir de nodules de carbonates de calcium prélevés non loin de la base de la formation limoneuse à Foum el Hassan, qui jette le doute sur un âge Soltanien.

2 Déterminations chronologiques

Au cours de ces recherches, des coquilles d'escargots terrestres ont été trouvées à faible profondeur, sous la surface dans la feija Seyad, à l'est de Tarjijcht. Deux échantillons d'un site (longitude : N29°03,99 ; latitude : W9°19,17), prélevés à −1,0 et −1,5 m sous la surface, dans des limons sableux fins, ont été datés respectivement par comptage radiométrique standard et par AMS (Tableau 1).

14C Data.

| Depth | Sample ID | 13C/12C | Conv. RC Age | 1s Calibrated age range (yr BP) |

| −1.0 m | Beta-116993 | −7.9 0/00 | BP | 11 340–11 940 |

| −1.5 m | Beta-142108 | −8.1 0/00 | BP | 12 670–13 130 |

Les échantillons destinés à la datation par luminescence optique (Tableau 2) ont été prélevés dans différents sites des feijas ; cette note rend compte d'analyses test sur trois échantillons des alluvions du Tissint (longitude : N29°54,5 ; latitude : W7°21,7) (Fig. 2). L'échantillon 1 provient des limons sommitaux, à 0,4 m sous la surface, l'échantillon 2 d'une lentille sableuse au sein du membre graveleux inter-limon et l'échantillon 3 de limons argileux du membre limoneux basal.

Luminescence data.

| Sample | Equivalent | Radioisotopes | Depth | Cosmic | Moisture | Dose rate | Age | ||

| dose (Gy) | K (%) | Th (ppm) | U (ppm) | (m) | (Gy ka−1) | (WF) | (Gy ka−1) | (ka) | |

| Wet model | |||||||||

| Sample 1 | 40.6±2.1 | 2.32±0.04 | 7.26±0.10 | 3.74±0.05 | <1 | 0.20±0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.04 | 3.01±0.14 | 13.5±0.9 |

| Sample 2 | 97.7±4.8 | 2.30±0.03 | 8.35±0.07 | 2.04±0.02 | 15 | 0.05±0.01 | 0.30 ± 0.04 | 2.47±0.13 | 39.5±2.8 |

| Sample 3 | 72.1±4.3 | 0.52±0.02 | 2.44±0.03 | 7.75±0.14 | 25 | 0.03±0.01 | 0.50 ± 0.07 | 1.60±0.09 | 45.0±3.7 |

| Dry model | |||||||||

| Sample 1 | 0.01 ± 0.03 | 3.82±0.15 | 10.6±0.7 | ||||||

| Sample 2 | 0.012 ± 0.03 | 3.31±0.15 | 29.6±2.0 | ||||||

| Sample 3 | 0.02 ± 0.05 | 2.50±0.12 | 28.9±2.2 |

3 Discussion

Les datations 14C sont stratigraphiquement cohérentes. Les âges déterminés doivent être maximums, étant donné la possibilité d'inclusion de carbonates non organiques, plus anciens, dans les coquilles, bien que les rapports isotopiques indiquent que cette contamination semble faible. En effet, de telles considérations améliorent la corrélation avec les résultats obtenus par luminescence optique sur l'échantillon 1.

Les âges LOS dépendent en partie du modèle d'humidité considéré pour les échantillons. Si l'on assume que l'échantillon 1 a été sec depuis son dépôt, l'âge de 11,3–9,9 ka, dans le scénario sec, s'accorde très bien avec l'âge 14C de 11,34–11,96 ka BP cal., obtenu environ 5 m plus bas stratigraphiquement. L'échantillon 2, issu d'un niveau asséché, peut être considéré comme ayant été essentiellement sec depuis son dépôt ; il est suggéré que son âge réel se place plus près de 27,6–31,6 ka que le modèle humide. Quant à l'échantillon 3, il a dû être de manière prédominante humide, jusqu'à ce que les rivières aient entaillé jusqu'à leur niveau actuel, sans doute à l'Holocène tardif. C'est pourquoi il semble raisonnable d'accepter, pour les limons de base, un âge plus proche du modèle « humide », à 41,3–48,7 ka, que de celui du modèle sec.

4 Conclusions

Les datations déterminées ici sont en très bon accord avec les âges maximum et minimum publiés pour les sédiments soltaniens ailleurs au Maroc, à savoir 14C ans BP et ans 14C BP [3,7,9]. En outre, Delibrias et al. [6] suggèrent que les limons supérieurs du Soltanien II ont des âges compris entre et ans 14C BP (Gif 3621, âge obtenu de la même façon sur Rumina dec.), tandis que Weisrock et al. [10] identifient, dans la succession de l'oued Tamdroust, un hiatus entre les limons inférieurs FR1 et les limons intermédiaires FR 2 vers 30 000 ans 14C BP. Ces données sont en bon accord avec les datations indiquées ici, à savoir 29,6±2,0 ka, pour le niveau graveleux inter-limon et 11,34–11,94 ans BP cal. et 10,6±0,7 ka pour le sommet du membre limoneux supérieur.

Il est tentant de corréler le membre limoneux inférieur et le faciès de chenal inter-lit avec le stade 3 et les limons supérieurs avec le maximum glaciaire du stade 2 (isotopes de l'oxygène). Cependant, il est prématuré de proposer une interprétation climatique et génétique des ces formations, alors que les analyses sédimentologiques sont en cours et avant qu'un lot supplémentaire de datations LOS ne soit fourni.

1 Introduction

The Anti Atlas mountains, between ‘Massif du Kerdous’ to the west and Massif El Graara 250 km to the east, are drained southwards by the rivers Seyad, Tamanart, Aguemmamou, Akka, Tata, Myit, Tissint and Alougoum. All, save the Seyad, are right bank tributaries to the Oued Draa (Fig. 1).

Where these rivers leave their valleys incised into the mountains and plateaus of the Precambrian metamorphic massifs and their Late Proterozoic and Cambrian limestone and schist cover rocks, they cross a terrain of alluvial plains, fans, glacis, regs and cuestas in the folded Ordovician to Devonian formations to the south. Between the mountain front and the high escarpment of Jebel Bani is the first of the extensive alluvial plains locally called ‘feijas’. The rivers pass through the Jb. Bani in gorges or ‘foums’.

These feijas contain extensive deposits, 30–380 km2, of fine sandy silts 5–30 m thick that are currently being dissected by the gravel transporting rivers into ‘badland’ topographies and extensive flat-topped terraces. At the feija margins, the silts onlap and bury the fans, cones and glacis of the adjacent hill slopes. The silts can be traced back into the mountains as terraces that contrast sharply in their fine textures from the cobble beds of the present rivers and the regs, screes, and bare rocks in the mountains. The silt formations continue through the Jb. Bani foums and form vast flat sediment plains such as those south of Tata, Akka and Foum el Hassan that extend down to the O. Draa.

The silt formations vary in thickness. In the Bani feijas, the thickness increases from ca 5 m near the mountain front to 30 m at the Bani foums. Most sections (Fig. 2), show three members – a basal silt member, an inter-silt channel gravel member and a top silt member. The ‘silt’ formations are abruptly underlain by thick conglomerates of well-rounded cobbles cemented into a massive calcrete and cementation extends several metres up into the overlying silts. The silt terrace surfaces are frequently covered by thin (<0.3 m) sheets of well-rounded pebbles and cobbles, marking the return to gravel transporting fluvial systems, and by angular clasts near the glacis slopes, marking a reactivation of slope processes.

The bottom silt member, 3–5 m thick, comprises thin, flat lying and planar bedded clayey silts, silty clays, with rare sandy silt layers. In the Tissint feija, the lower silts contain sodium chloride evaporite beds and marly clays. Colours are varied and range from red, beige to white.

The inter-silt gravel member is generally 1–3 m thick and contains flat bedded to cross bedded silty sands with gravel and pebble lenses, multiple trough cross bedded gravels characteristic of braided channels and planar bedded sandy matrix cobble gravels. Where these channel facies occur near the feija margin hillslopes, the fans, cones and glacis' merge into the ‘inter-silt’ fluvial channel strata. Thus hill slope processes were ‘active’ during the period when gravel bedded rivers flowed through the feijas.

The top silt member comprises flat bedded, silty fine sands and sandy silts which become slightly more sandy towards the top of the succession. Down-feija this upper silt member increases in thickness from several metres to 20 m, bedding becomes more pronounced and silty clay beds appear. Calcium carbonate enriched zones occur in the upper silts and generate indurated benches in the walls of the trough shaped wadis.

These silty and silty sand alluvial formations are the result of climatic and geomorphological conditions greatly differing from those that preceded them and those that followed them during the Holocene. They were deposited during prolonged, wide-flooding, low energy flows with high concentrations of suspended sediments. The sediments were sourced from the erosion of deeply weathered mantles and matrix-rich slope colluvia in the mountains and from dust or loess fallouts whose source areas have yet to be identified. The inter-silt gravel member indicates a return to high-energy river flows and frequent slope erosion events.

Apart from Dijon [4] and Andres [2], little has been published on these extensive formations of the southern Anti Atlas. Their stratigraphy is not unlike that of the alluvial Soltanian sediments elsewhere in Morocco summarised and dated by Delibrias et al. [3], Rognon [6] and Weisrock [8]. However, Andres [2, p. 46] reports a single 14C determination of conv. yr. BP from calcium carbonate nodules near the base of the silt formation in Foum el Hassan that casts doubt on a Soltanian age.

2 Chronological investigations

In the course of the present investigation, shells of the land snail Rumina decollata have been found at shallow depths below the surface in the Seyad feija east of Tarjijcht. Two samples from one site at N29°03.99, W9°19.17, taken from −1.0 and −1.5 m below the surface, in fine sandy silts, were dated by standard radiometric counting and by AMS respectively (Table 1).

Samples for optical luminescence dating (Table 2) have been taken from a number of sites throughout the feijas and this paper reports on the trial analysis of three samples from the Tissint alluvia at long. N29°54.5, lat. W7°21.7 (Fig. 2). Sample 1 came from the top silts at 0.4 m below the surface, sample 2 from a sand lens within the inter-silt gravel member, and sample 3 from clayey silts in the lower silt member.

For optical dating, quartz grains in the 90–150 μm size fraction were extracted from the samples and ca 3.4 mg aliquots of refined quartz were mounted onto 10 mm diameter aluminium discs. Assessment of long-lived radioisotope concentrations, and corresponding environmental dose rates were measured from the samples via inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP–MS). Moisture within the sediment matrix attenuates a typically small portion of the radiation dose, which would otherwise been absorbed by the sediment. However, as the saturation moisture contents (W) and the average field moisture conditions during the burial periods (F) of the samples are not well known, we have chosen to develop two age models based on generally moist and on generally dry sediment burial conditions. Conversion from radioisotope concentrations to dose rate followed Adamiec and Aitken [1].

All optically stimulated luminescence measurements were conducted using an automated RISO TL/OSL DA-15 reader fitted with a blue (λ=470 nm) diode array (), and a calibrated 90Sr/90Y beta radioactive source. The luminescence signal emitted from the samples was measured with a photomultiplier (type 9235QA, series 101482) filtered with two Corning U-340 glass filters. Equivalent dose (De) estimates were calculated using the recently developed single aliquot regeneration technique (SAR) [5]. The SAR procedure uniquely allows for the determination of a De using a single aliquot, which avoids any need for inter-aliquot normalisation, improves the precision of De estimates by incorporating interpolative (versus extrapolative) estimation techniques and includes a series of internal checks, which monitor and correct any changes in the behaviour of the aliquot during the procedure. An average of nine aliquots was used to estimate the mean sample De and its associated standard error. The results are summarised in Table 2.

3 Discussion

The 14C dates are stratigraphically coherent. The ages reported may be maximums, given the potential for inclusion of older non-organic carbonates in the shells, although the isotopic ratios indicate that this contamination may be limited. Such considerations, in fact, improve their ‘correlation’ with OSL sample 1.

The optical ages depend partly on the moisture model assumed for the samples. Assuming that sample 1 has been dry since deposition the dry scenario date of 11.3–9.9 ka accords well with the 11.34–11.96 ka cal. 14C BP date stratigraphically ca 5 m lower. Sample 2, from a free-draining stratum, can be assumed to have been dominantly dry since deposition and it is suggested that the true age lies nearer to the 27.6–31.6 ka date than to the wet model age. Sample 3, from a silty clay bed in the lower silt member may have been dominantly moist until the rivers incised to their present level some time in the Late Holocene. It would seem reasonable, therefore, to accept an age for the bottom silts nearer to the wet model of 41.3–48.7 ka than to the dry model age.

4 Conclusions

These dates accord very closely with the maximum and minimum published dates for Soltanian I and II sediments elsewhere in Morocco of 14C yr BP [3,7] and 14C yr BP [9]. Furthermore, Delibrias et al. [3] suggest that the upper silts of Soltanian II range are bracketed by and 14C yr BP (Gif 3621 similarly on Rumina dec.), whilst Weisrock et al. [10] identify, in the O. Tamdroust succession, a hiatus between their lower silts FR1 and middle silts FR2 at ca 30 000 14C yr BP. These dates accord with the dates reported here: 29.6±2.0 ka, for the inter-silt gravels and 11.34–11.94 cal. yr BP and 10.6±0.7 ka for the top of the upper silt member.

It is tempting to correlate the lower silt member and the inter-silt channel facies with oxygen isotope stage 3 and the upper silts with the Glacial maximum of oxygen isotope stage 2. However, it is premature to suggest a climato-genetic interpretation on these formations while sedimentological analyses are in progress and before the further batch of optical age determinations is completed.

Acknowledgements

Martin Thorp thanks the UCD Department of Geography and University College, Dublin, for funding to support field work and dating and Mr Eamon Grant and Ms Cleo Manning for field assistance. The authors are grateful for suggestions for made by Prof. A. Weisrock and by Dr M. Fontugne and for improvements to the translations by the French Academy of Sciences.