1 Introduction

Johan [11] investigated the compositional plane of spinels (Fe3O4FeCr2O4MgAl2O4) and found that spinels showing an association with sulphides such as Cu–Ni sulphides, are characterised by Mg–Al cationic relations as 2 MgAl<0, whereas those which are barren (no mineralisation of sulphides or such) should show 2 MgAl>0. In the model, Johan developed a discriminant function:

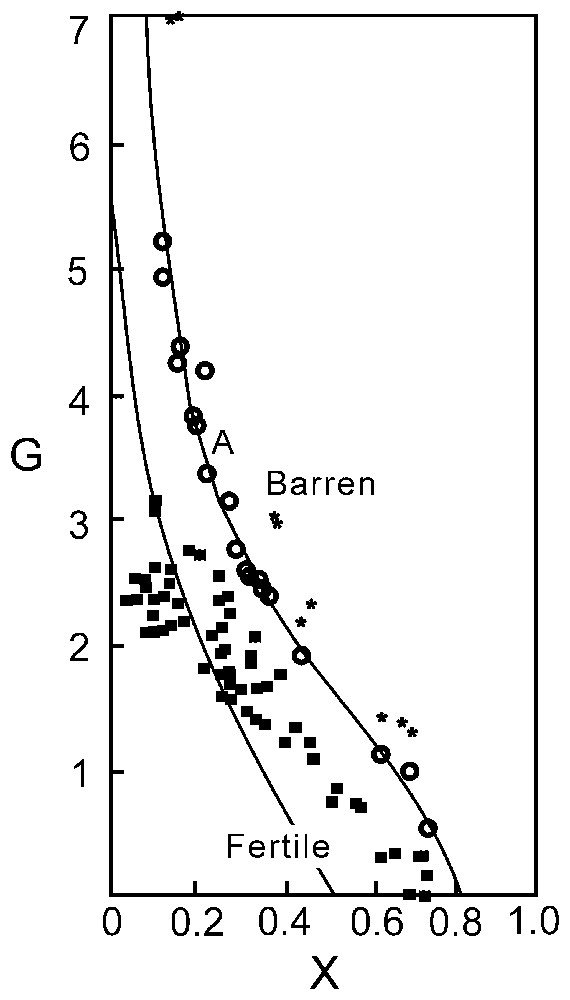

The function is graphically represented as curve A in Fig. 1. Spinels, devoid of sulphide (or such) phases, should plot above this curve while those with such mineralisation should plot below this curve.

Graphical expression (curve A) of the with X=Mg/(Mg+Fe2+). Staré Ransko spinels (■), Horni Bory spinels (★) and Nuggihalli spinels (○).

Expression graphique (courbe A) de avec X=Mg/(Mg+Fe2+). Spinelles de Staré Ransko (■), spinelles de Horni Bory (★) et spinelles de Nuggihalli (○).

With strange serendipity, the chemistry of different grains of a series of samples collected from the chromite bodies of Nuggihalli (stretching nearly north–south over a distance of 50 km) was observed to plot remarkably on the demarcating line and thereby prove the ingenuity of Johan in postulating the trend.

2 Geology of the study area

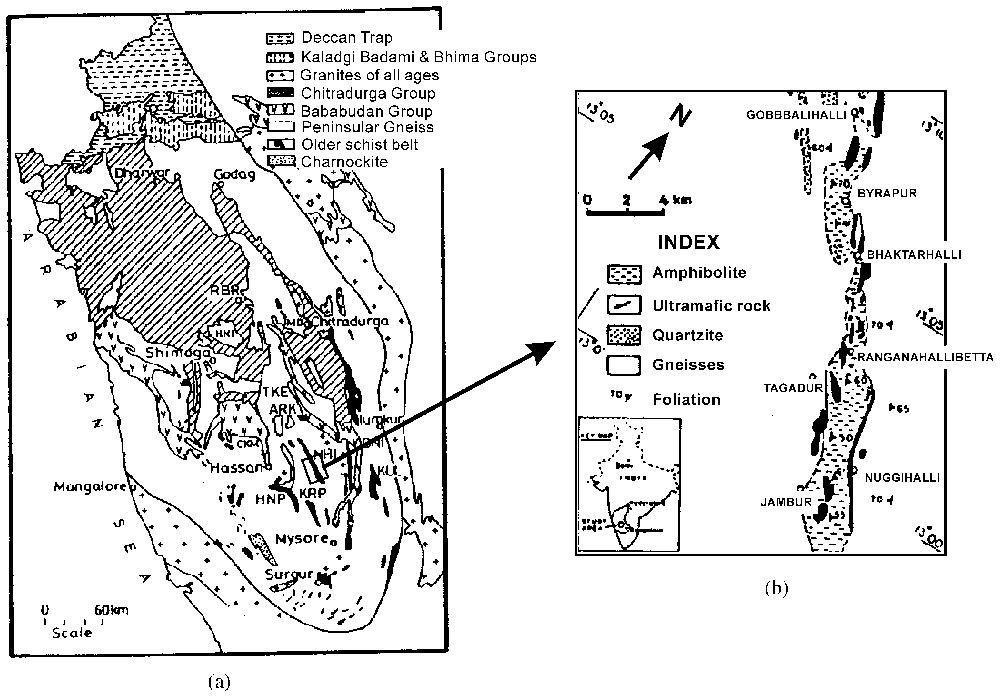

The Nuggihalli schist belt (3.0–3.5 Ga; e.g., [14]) occurs as a band of low-grade metamorphosed ultramafic bodies stretching roughly NW–SE to north–south in the Dharwar craton, belongs to the greenstone belt in South India (see map, Fig. 2). Ultramafic rocks of the area consist of unaltered dunite, harzburgite, chromite bearing serpentinite, and talc–chlorite–tremolite schist. Other major rock types are amphibolite, metasediments (fuchsite quartzite, quartz–mica–chlorite schist and staurolite–quartz–mica schist), tonalite trondhjamitic gneisses and meta-anorthosite. Titanomagnetite bodies rich in vanadium are intercalated with the ultramafic rocks. The area under study has been subjected to greenschist-to-amphibolite facies metamorphism and shows increase in grade from north to south [19].

(a) Geological map of part of the Dharwar craton following Radhakrishna and Naqvi [18]. NHI: Nuggihalli; KUL: Kunigal; KRP: Krishnarajpet; HNP: Holenarasipur; RBR: Ranibennur. (b) Geological map showing section of the Nuggihalli schist belt from which the samples have been collected (modified from [10]).

(a) Carte géologique d'une partie du craton de Dharwar selon Radhakrishna et Naqvi [18]. NHI : Nuggihalli ; KUL : Kunigal ; KRP : Krishnarajpet ; HNP : Holenarasipur ; RBR : Ranibennur. (b) Carte géologique montrant une coupe de la ceinture schisteuse de Nuggihalli, dont sont issus les échantillons étudiés (modifié d'après [10]).

The chromite bodies occur commonly as layers, high angle bands and in irregular tabular or lensoid forms within serpentinite. The size of the chromite deposit varies from lenticular bands ∼300 m in length, with a width of 6 m at Tagadur mines and pods of a few metres to more than 60 m size, extending to a depth of ∼100 m in Byrapur underground mine. The spectacular rosy moss-like aggregates of pink chlorite (Cr-bearing clinochlore) occur as veins and fracture fillings and as pockets in grey chromite ore bodies [4]. Based on the presence of pillow structure and spinifex texture in peridotite, Naqvi and Hussain [15] suggested submarine extrusion to have occurred. From the Cr/Al ratio in serpentinite, komatiitic affiliation was deciphered by Sudhakar [22]. The identification of a komatiitic affinity for the ultramafic rocks of the belt led to the suggestion by these investigators that this belt is an example of Barberton type greenstone belt, in which the komatiitic rocks are considered to be pristine and primordial. The Cr/Fe ratio of chromite indicates a layered intrusion complex [16].

Probable stratigraphic succession of the belt modified from the one reported by Jafri et al. [10] is presented below:

- – dolerite dyke,

- – meta-anorthosite,

- – gneisses,

- – dunite,

- – titanomagnetite, gabbro, metasediments,

- – amphibolite,

- – perodotite/serpentinite, with bands of chromite, tremolite–talc schist.

3 Chemical study

The chromite samples were collected from chromitite bodies which run as bands and lenses within serpentinised masses. The chromite samples were chemically analysed by a JEOL-733 electron microprobe with wavelength dispersive method at 15 kV with a beam current of 10 nA and a beam diameter of 10 μm. Average spectrum counts (10 s×5 times) were compared with natural standards and data were corrected by the Bence and Albee method [3]. The minerals that were used as the standards are; albite for Si and Na, almandine for Al and Fe, olivine for Mg, rhodonite for Mn, rutile for Ti, diopside for Ca and sanidine for K. Table 1 shows the chemistry of studied chromites. Detail chemistry of relict and metamorphosed mineral phases (viz., olivine, pyroxene, amphibole, chlorite, etc.) will be presented in a subsequent paper.

Average chemical formulae of the Cr-spinels from Nuggihalli schist belt

Formules chimiques moyennes des spinelles chromifères de la ceinture schisteuse de Nuggihalli

| Gob 7i |

| Gob 7ii |

| G1 |

| By 3 |

| By 5 |

| By |

| By 1 |

| B |

| T4 |

| Tag 4i |

| Tag 4ii |

| T |

| T6 |

| J2 |

| J1 |

| J4 |

| Jam 6i |

| Jam 6ii |

| JCM 3 |

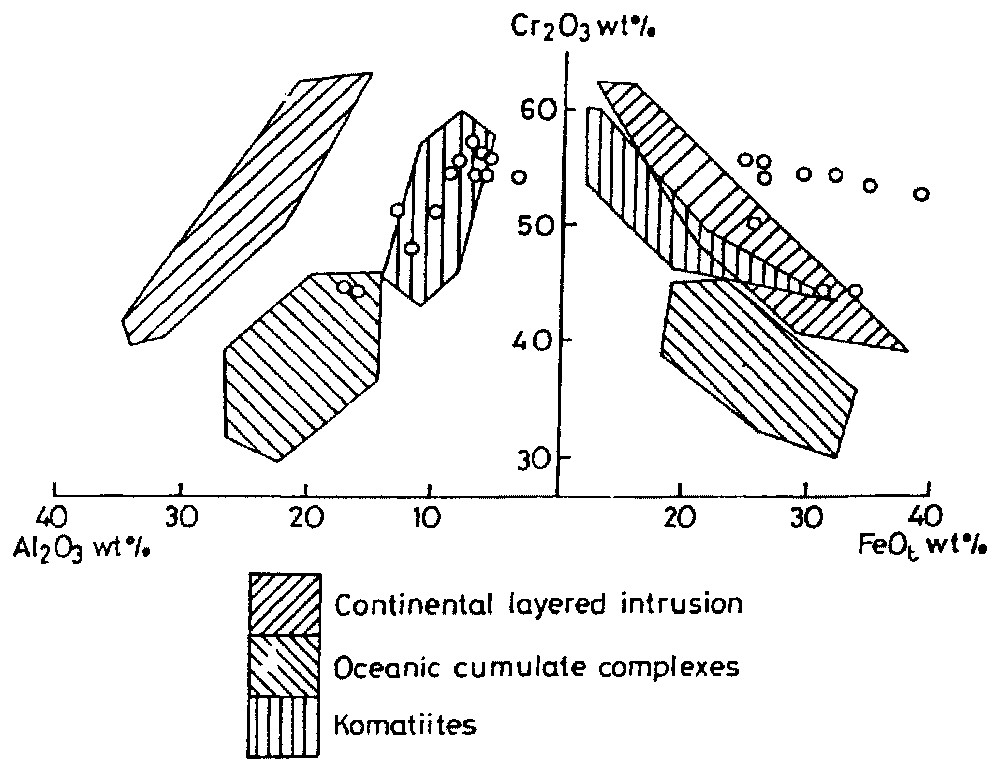

We have plotted the chromite chemistries in 100×Cr/(Cr+Al) (Cr∗) vs 100×Mg/(Mg+Fe2+) (Mg∗), which revealed that the studied samples fall in the cluster of the well-known stratiform deposits of the world. The modified 100×Fe3+/(Cr+Al+Fe3+) (Fe3+•) vs 100×Mg/(Mg+Fe2+) (Fig. 3) and Cr2O3 vs Al2O3 wt% (Fig. 4a) plots show the komatiitic affinity of the chromitite bodies. However, FeO (total) vs Cr2O3 (Fig. 4b) simultaneously brings out its continental layered characteristics. From these plots, it can be emphasised that the chromite from the komatiites and stratiform deposits fall in the same compositional field. We have used Rollinson's Cr/(Cr+Al) vs Fe2+/(Fe2++Mg) plot [20] (Fig. 5) to compare the studied chromitites with reported komatiitic chromitite of Zimbabwe (Belingwe, Inyala and Shurugwi). They all fall in the same range (Cr/(Cr+Al) varying from 0.6 to 0.9 whereas Fe2+/(Fe2++Al) from 0.26 to 0.87) as reported. This comparison is instructive, because the mentioned komatiites are the most studied and offer the best opportunity to study primary magmatic mineral deposits. We have also plotted our chromite data in the Barnes and Roeder [2] longitudinal spinel projections of Cr/(Cr+Al) and Fe3+/(Cr+Al+Fe3+) vs Fe2+/(Mg+Fe2+) and TiO2 vs Fe3+/(Cr+Al+Fe3+) diagrams. All the studied samples show their komatiitic affinity.

Composition of chromite plotted on projections of the spinel prism of Steven's [21]. The fields for the various types of complexes shown are based on [5,7,9,24].

Compositions de chromite représentées sur des projections de prisme des spinelles de Steven [21]. Les champs des différents types de complexes représentés sont basés sur les données de [5,7,9,24].

Discrimination diagrams for chromite composition plotted in terms of Cr2O3 vs Al2O3 and Cr2O3 vs FeOt. Modified from a four-component diagram of [1].

Diagrammes de discrimination pour des compositions de chromite représentées en termes de Cr2O3 vs Al2O3 et Cr2O3 vs FeOt. Modifié à partir d'une diagramme à quatre composants [1].

Cr/(Cr+Al) vs Fe2+/(Fe2++Mg) [20] plots of the studied Cr-spinels in comparison with chromitites from komatiites of (a) Inyala and Belingwe greenstone belts, Zimbabwe (b) Inyala, Shruguwi, Zimbabwe and Bushveld intrusion, South Africa.

Diagrammes de Cr/(Cr+Al) en fonction de Fe2+/(Fe2++Mg) [20] par les spinelles chromifères étudiés, comparés aux chromitites des kromatiites (a) des ceintures de roches vertes d'Inyala et de Belingwe, Zimbabwe, (b) de l'intrusion d'Inyala, Shruguwi du Zimbabwe et du Bushveld, en Afrique du Sud.

4 Thermal history of the chromite

The chromite–olivine assemblage has been used to determine the temperature of formation of the chromite ores. The calibration proposed by Fabries [8] has been used to determine the temperature in the present study. This thermometer is successfully applied to the olivine having Fo content ∼90% and it has reasonably been used in the present case, since the Fo content of the olivine (83–92%) is close to that value. Detail chemistry will be presenting elsewhere. The thermometric relation is:

In the above equation,

The Fe2+ and Fe3+ contents in chromites have been based on stoichiometric calculations. Using the above equation, the temperature of formation of Nuggihalli chromite has been determined as 1178 °C.

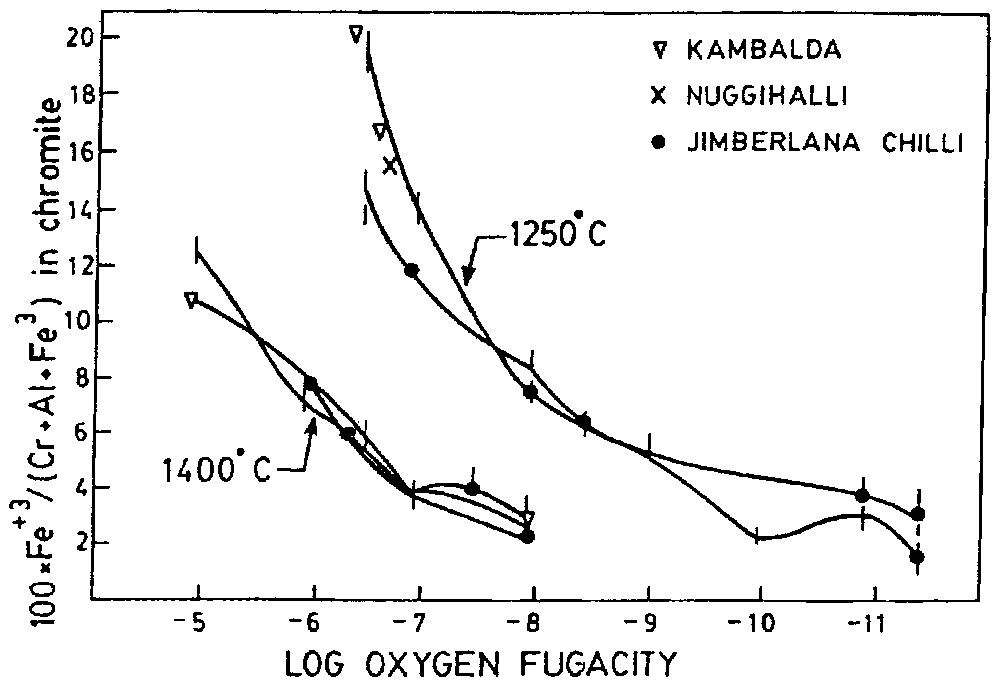

5 The fO2 determination

The oxygen fugacity of the chromite from the Nuggihalli schist belt has been determined by the method discussed in [13]. According to this method the fO2 is determined from Fe3+/(Cr+Al+Fe3+) ratio of chromite owing to its strong dependence on fO2 and very weak dependence on the melt composition. To determine the fO2 of Stillwater and Bushveld complex, some [13] used this method, the results of which are consistent to the estimation by other methods. The fO2–T paths of natural basalt are sub-parallel to QFM (quartz–fayalite–magnetite) buffer curves [6]; therefore, fO2 of natural magma decreases with decreasing temperature. For this reason, to eliminate the normal temperature effect fO2 values are expressed relative to one of buffer curves. Error in 200 °C temperature of crystallisation makes an error in fO2 values only of 0.5 log unit. The EPMA and Mössbauer study lead to the determination of 100×Fe+3/(Al+Cr+Fe3+) as 15.6. The temperature of formation of Nuggihalli chromite has been determined from olivine–spinel geothermometer as 1178 °C. Since most of the chromitite layers form within 1250±100 °C, curves at that temperature of Fig. 6 are reasonable [13]. Therefore, the 1250 °C curve of Fig. 6 has been used to determine log fO2, which comes as −6.67.

100×Fe3+(B)/[Cr+Al(B)+Fe3+(B)] (atomic proportion) in chromites as a function at 1250 °C and 1400 °C (after [13]).

100×Fe3+(B)/[Cr+Al(B)+Fe3+(B)] en fonction de la fugacité de l'oxygène à 1250 °C et 1400 °C (selon [13]).

6 Discussion

The Nuggihalli chromite which crystallises at ∼1180 °C with an oxygen fugacity of −6.67, appearing from their chemical plots (Figs. 3–5) indicates their komatiitic affinity. Working on the Cr-spinels from the Staré Ransko gabbro-peridotite, Czech Republic, van der Veen and Maaskant [23] reported that all the spinels from the investigated samples plotted below the discriminant curve A (Fig. 1), which indicates a strong possibility for sulphide mineral association. This indeed was true. While the spinels from the Horni Bory xenoliths [12], showing no evident presence of sulphides etc. plotted distinctly above the discriminant curve. Much to the surprise of the present authors the spinels of Nuggihalli plot remarkably along the curve itself. This observation reinforces the logic of van der Veen and Maaskant [23] and redefines the validity of the profile of the boundary curve of Johan [11].

Fig. 1 shows that all the spinels from Nuggihalli schist belt plot on the discriminant curve A but a few plot within the barren zone close to the A curve. This evidently points the possibility of chromitite band (along with its silicate host rocks) being barren rather than fertile. This observation eliminates the strong possibility for chromitite to host any mineralisation of sulphides or their kind.

The reported occurrence of sulphides [17] (chalcopyrite, pyrite, pyrrhotite, cubanite and pentlandite) in the close proximity of the ultramafic intrusions in this belt is inevitably seen to be confined within the marginal part of gabbroic masses, intrusive into the ultramafic (later metamorphosed) bodies hosting the chromite and titanomagnetite bands.

The validity of the discriminant curve A of Johan [11] thus receives a further endorsement from the chromite characters of the greenstone belt of south India.

Acknowledgements

The authors express sincere thanks to Prof. H.S. Moon of Yonsei University, Seoul, for the EPMA analyses, and Mysore Minerals Ltd. for all cooperation in the field work. Authors are much thankful to the two anonymous reviewers for constructive and encouraging reviews. Thanks to Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India for the financial support.