Version française abrégée

Le comportement environnemental des déchets de la métallurgie des métaux de base a été intensément étudié au cours de ces dernières années [8–11]. Les mattes résultant de la métallurgie du plomb sont considérées comme les déchets toxiques n∘ 10 04 00, conformément au catalogue de l'Union européenne [5]. Cet article est focalisé sur l'altération atmosphérique des mattes et sur la distribution des éléments toxiques au sein des produits néoformés. Les mattes et leurs produits d'altération ont été échantillonnés sur les haldes de l'usine métallurgique située à Lhota, près de la ville de Přı́bram en République tchèque [8–11]. Les échantillons ont été étudiés par diffraction des rayons X (DRX), microscopie optique et électronique à balayage (MEB), microsonde électronique (MSE).

Les études effectuées [9,10,14] ont montré que les mattes sont constituées par des sulfures, des arséniures, des composés intermétalliques et des métaux purs. Le plomb se présente sous forme de métal ou comme PbS (galène). Le cuivre forme essentiellement des sulfures, tels que la bornite, la digénite et la cubanite, mais également des arséniures (koutekite) ou des antimoniures (cuprostibite). Le zinc se présente exclusivement sous forme de wurtzite (ZnS). Quant au nickel, il forme plusieurs composés intermétalliques (NiSb, Ni3Sn2, NiAs). La pyrrhotite est très fréquente dans les mattes étudiées [9,10].

Les oxydes de fer hydratés, tels que la phase amorphe Fe(OH)3 (ferrihydrite) et la goethite (FeOOH) forment des encroûtements, remplissent des fissures et des cavités dans les mattes, où ils se présentent en cristaux aciculaires (Figs. 1 et 2). L'étude aux rayons X a révélé la présence de goethite, de lépidocrocite et probablement aussi d'akaganéite [15]. Les analyses à la microsonde électronique des oxydes de fer hydratés ont montré de fortes concentrations en métaux et métalloı̈des (jusqu'à 2,07 % Pb, 0,91 % Cu, 0,25 % Zn et 4,63 % As, voir Tableau 1), dues à des processus de co-précipitation et d'adsorption [2,19,22,23,27]. Par rapport au zinc, Pb et Cu sont adsorbés à la surface des oxydes de fer hydratés à un pH plus faible [2,7]. Compte tenu de faibles teneurs en Zn des oxydes de fer (Tableau 1), leur précipitation se serait produite dans des conditions faiblement acides. L'hydroxyde de cuivre Cu(OH)2, qui se présente en aiguilles bleu foncé sur les mattes riches en Cu, indique un milieu neutre ou faiblement alcalin [7,13,20].

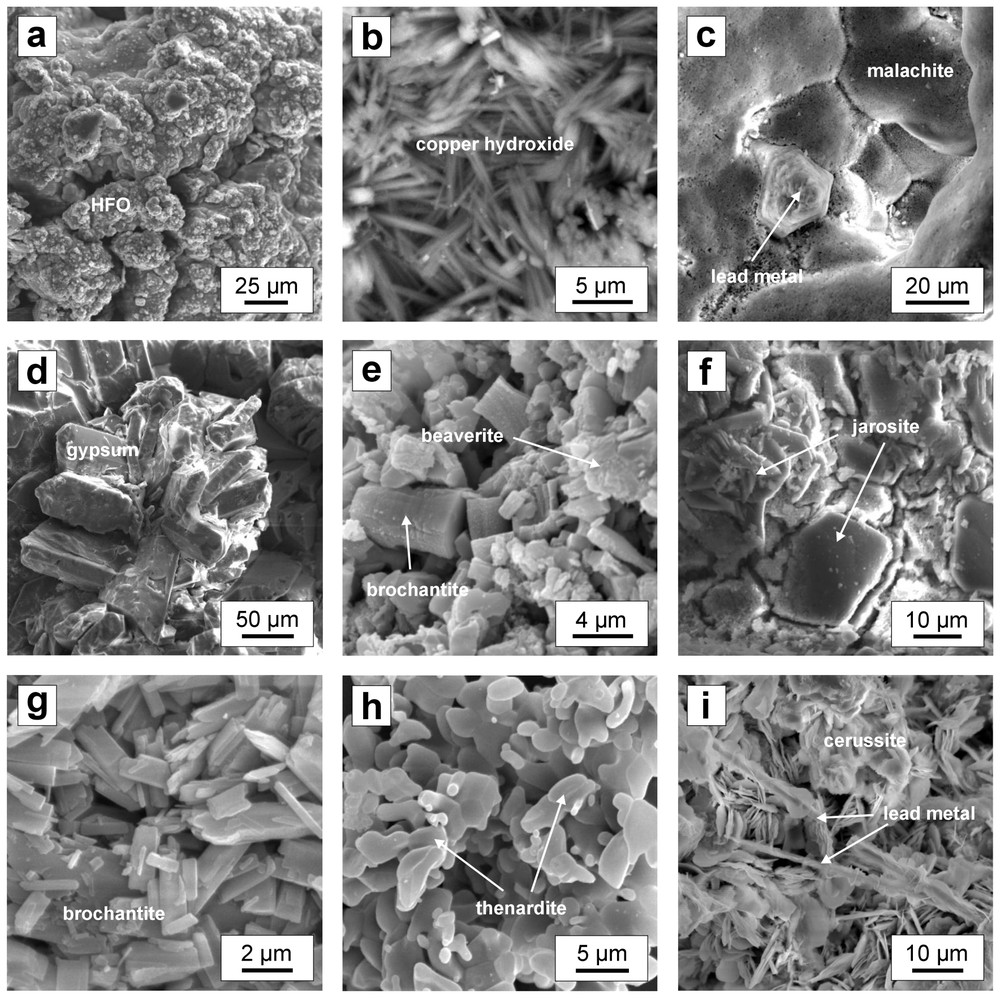

SEM micrographs of alteration products of mattes (in secondary electrons): (a) spherulite aggregates of hydrous ferric oxides (HFO); (b) copper hydroxide spears; (c) etched cubic crystal of metallic lead surrounded by reniform aggregates of malachite (Cu2(OH)2CO3); (d) bundles of gypsum (CaSO4·2 H2O) crystals; (e) subhedral crystals of brochantite (Cu4(OH)6SO4) associated with beaverite (PbCuFe2(SO4)2(OH)6); (f) platy crystals of jarosite (KFe3(SO4)2(OH)6); (g) aggregates of platy brochantite crystals; (h) aggregates of thenardite (Na2SO4); (i) platy cerussite (PbCO3) developed on lead metal needles.

Images MEB des produits d'altération des mattes (en électrons secondaires): (a) cristaux globulaires d'oxydes de fer hydratés; (b) aiguilles d'hydroxydes de cuivre; (c) cristal altéré de plomb métallique entouré d'agrégats de malachite (Cu2(OH)2CO3); (d) agrégat de cristaux automorphes de gypse (CaSO4·2 H2O); (e) cristaux automorphes de brochantite (Cu4(OH)6SO4) associés à la beaverite (PbCuFe2(SO4)2(OH)6); (f) cristaux aplatis de jarosite (KFe3(SO4)2(OH)6); (g) agrégats de cristaux de brochantite; (h) agrégats de thénardite (Na2SO4); (i) cristaux aplatis de cérusite (PbCO3) développés à la surface du plomb métallique sous forme d'aiguilles.

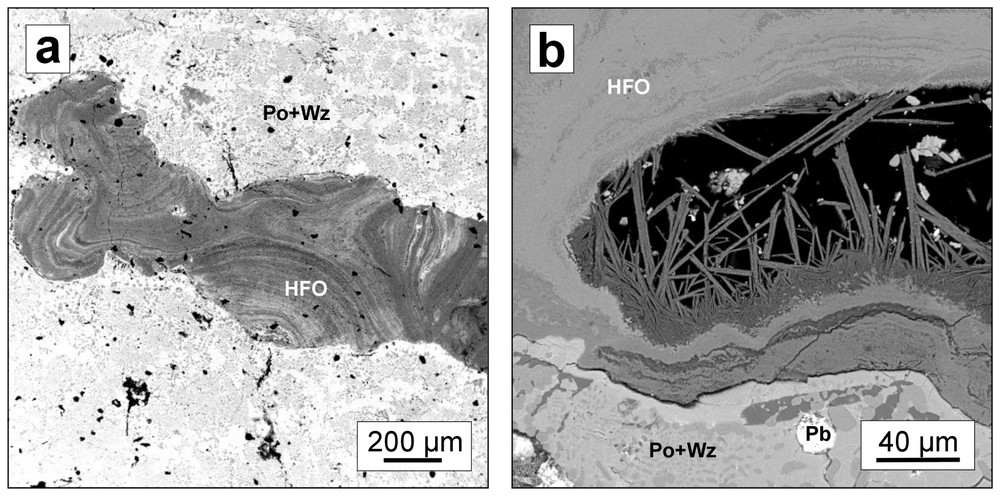

SEM micrographs of secondary hydrous ferric oxides (HFO) developed in cavities and fissures during the alteration of matte (in back-scattered electrons): (a) banded-layer formation of HFO resulting from the dissolution of Fe-rich sulphides; (b) development of perpendicular crystals of HFO in the cavity. Abbreviations: pyrrhotite (Po), wurtzite (Wz), lead metal (Pb).

Micrographies au MEB d'oxydes de fer hydratés néoformés, développés dans des cavités et fissures (en électrons rétrodiffusés): (a) formation de textures rubanées, composées d'oxydes de fer hydratés, résultant de la dissolution des sulfures de fer; (b) développement des cristaux perpendiculaires d'oxydes de fer hydratés; remplissage d'une cavité dans la matte. Abréviations: pyrrhotite (Po), würtzite (Wz), plomb métallique (Pb).

Examples of electron microprobe analyses of secondary hydrous ferric oxides (HFO) precipitated in cavities of altered matte. Chemical compositions are given in wt% and in at.%

Exemples d'analyses à la microsonde électronique d'oxydes de fer hydratés néoformés, précipités dans des cavités de la matte. Les compositions chimiques sont données en % pondéraux et en % atomiques

| Analysis | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| wt% | |||

| Fe | 49.50 | 50.99 | 47.21 |

| Pb | 2.07 | 1.53 | 0.10 |

| Cu | 0.64 | 0.91 | 0.55 |

| Zn | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| As | 0.38 | 0.29 | 4.63 |

| Sn | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Sb | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Si | 0.60 | 1.52 | 0.12 |

| S | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.11 |

| Total | 53.77 | 55.55 | 52.84 |

| at.% | |||

| Fe | 93.87 | 91.28 | 91.39 |

| Pb | 1.06 | 0.74 | 0.05 |

| Cu | 1.06 | 1.43 | 0.93 |

| Zn | 0.40 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| As | 0.54 | 0.39 | 6.68 |

| Sn | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Sb | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Si | 2.26 | 5.40 | 0.47 |

| S | 0.71 | 0.60 | 0.37 |

Les sulfates peuvent tamponner des solutions riches en métaux [1,16,18]. Il s'agit de la brochantite (Cu4(OH)6SO4), qui est souvent associée à la beaverite (PbCuFe2(SO4)2(OH)6) [17]. La présence de la brochantite indique un pH faible et des concentrations en SO42− élevées [12,21]. Alpers et al. [1] ont montré que la beaverite fait partie des sulfates peu solubles et représente ainsi une phase qui contrôle la solubilité de Cu et Pb. La jarosite, KFe3(SO4)2(OH)6, se présente en cristaux xénomorphes aplatis. Sa présence indique des conditions de précipitation acides [6]. Le potassium provient probablement d'une dissolution partielle de la phase vitreuse des scories associées [8]. La thénardite, Na2SO4, est rare. Comme dans le cas de la jarosite, Na provient de la dissolution de la fraction vitreuse des scories [8]. Le gypse, CaSO4·2 H2O, forme des cristaux subautomorphes à la surface des mattes (Fig. 1). Notons que le gypse et la thénardite sont solubles et peuvent ainsi contribuer à l'enrichissement des solutions en ions SO42− [1,26].

Les carbonates apparaissent dans un environnement riche en CO2 et dans des conditions neutres à alcalines [1,7,28]. La cérusite, PbCO3, se présente en cristaux lamellaires (Fig. 1) [11], généralement associés avec le plomb métallique (Fig. 1). La malachite, Cu2(OH)2CO3, est observée à la surface de certaines mattes (Fig. 1) et demeure stable à pH>5 [24]. L'étude aux rayons X a permis de démontrer la présence du composé NaOH·2 PbCO3, associé à Cu(OH)2 et stable dans un milieu fortement alcalin [3].

L'étude des produits d'altération naturelle des mattes indique une forte variation de pH (Fig. 3). Par conséquent, il est difficile de proposer des conditions optimales pour leur stockage [25]. Dans le cas où les mattes ne peuvent pas être recyclées, il faut les stocker dans un dépôt contrôlé et équipé de barrières géotechniques [4].

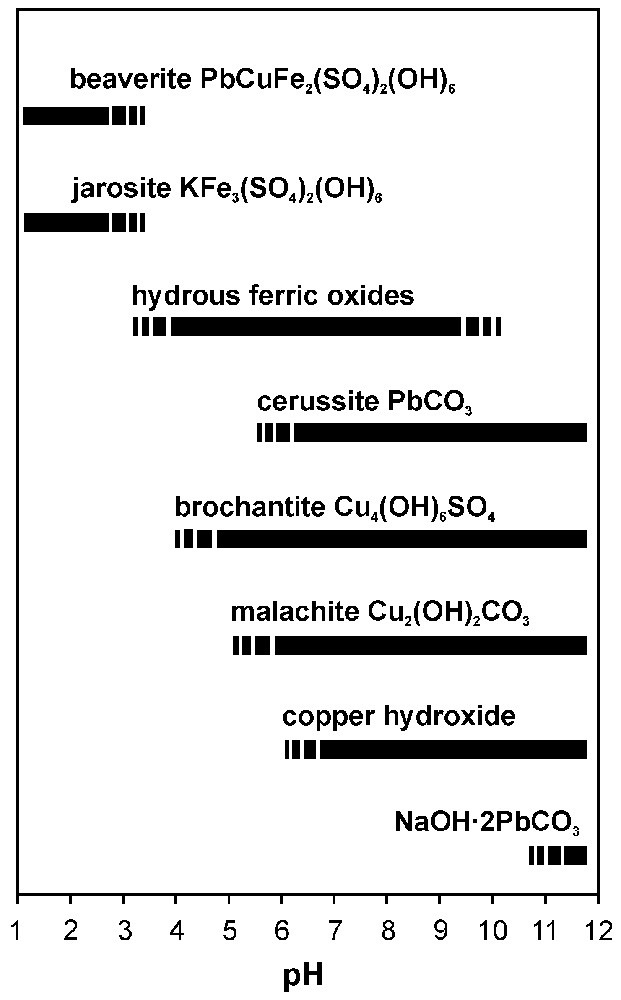

Approximate stabilities of various matte alteration products in oxidising conditions as a function of pH (compiled from [3,6,7,24]).

Stabilités approximatives des produits d'altération des mattes sulfurées dans des conditions oxydantes en fonction du pH (compilé selon [3,6,7,24]).

1 Introduction

The environmental behaviour of waste materials from metallurgy of base metals has been recently extensively studied [11]. Sulphide ‘mattes’, although not produced in such large quantities as metallurgical slags, nevertheless represent important waste materials, resulting from the primary and secondary lead-smelting process. Mattes are defined as solid solutions of metallic sulphides [14]. During the lead-smelting process, they serve as collector of sulphur and impurities in a sulphide phase [14] (Z. Kunický, technical director of the Přı́bram smelter, personal communication). It should be remembered that the mattes from lead metallurgy correspond to the category of “wastes from lead thermal metallurgy” (no. 10 04 00) according to the European Waste Catalogue (Commission Decision 94/3/EC, [5]). As a result, European legislation defines such material as “hazardous waste”.

This paper is based on previous studies devoted to the distribution (heavy metals and metalloids) and the crystal chemistry of toxic elements in mattes [9,10]. It focuses on natural alteration features of mattes at atmospheric conditions and describes mineral products of long-term natural weathering processes, discussing possible attenuation mechanisms for inorganic contaminants in natural conditions. Such results are essential for the further management of mattes and for determining the best conditions for their dumping or possible reuse.

2 Material and methods

The samples of massive mattes and their alteration products were taken on slag dumps in the vicinity of the Přı́bram lead smelter, located at Lhota near Přı́bram, Czech Republic. Detailed information on the sampling area is given elsewhere [8,9]. The samples were subsequently analysed by X-ray diffraction (XRD; Siemens D5005) with the following analytical conditions: Cu Kα radiation, 25 mA, 35 kV, step-scan mode over the range 5–80° 2θ, step 0.01°, counting time 10 s. The Debye–Scherrer diffraction technique was used for small samples. Twenty-five polished sections previously studied [10] were examined for natural alteration features by optical microscopy in reflected light. Polished sections and secondary products were then investigated under a Jeol JSM 6400 scanning electron microscope equipped with Kevex Delta energy-dispersion spectrometer (SEM/EDS). Electron probe microanalyses (EPMA) were carried out using a Cameca SX-50 microprobe. The detailed analytical conditions and set of standards are given elsewhere [10].

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Mineralogy: an overview

As revealed in previous studies, massive mattes are composed of various sulphides, metals, arsenides and other complex intermetallic compounds [9,10]. Lead is commonly present in metallic form or as galena (PbS). Copper forms mainly sulphides such as bornite (Cu5FeS4), digenite (Cu9+xS5) and cubanite (CuFe2S3), but can occasionally occur as koutekite (Cu5−xAs2) and cuprostibite (Cu2Sb). Zinc occurs exclusively as wurtzite (ZnS). Pyrrhotite (Fe1−xS) is one of the most common primary sulphides in the studied mattes. Nickel forms various intermetallic compounds such as breithauptite (NiSb), Ni3Sn2 and NiAs.

3.2 Alteration features

3.2.1 Oxides and hydroxides

Hydrous ferric oxides (HFO) such as amorphous ferrihydrite (Fe(OH)3) or crystalline goethite (FeOOH) are commonly observed in alteration zones of mineral wastes and typically form in oxidic environments [9,11,16,19]. In the studied mattes, HFO form alteration crusts and globular aggregates (Fig. 1a). In polished sections, HFO occur either as banded-layered aggregates in fissures and cavities (Fig. 2a) or as perpendicular crystals (Fig. 2b). XRD revealed that the HFO precipitates are poorly crystallised. Diffraction patterns showed weak diffraction peaks at 4.241 and 2.462 Å, which correspond to goethite (FeOOH), and those at 3.328 and 2.473 Å, corresponding to lepidocrocite (FeOOH), and finally those at 7.404, 3.328 and 2.531 Å, suggesting the presence of akaganeite (FeOOH or Fe8(O,OH)16Cl1.3) [15]. EPMA performed on the HFO precipitates in cavities of altered matte revealed high concentrations of heavy metals and arsenic (up to 2.07 wt% Pb, 0.91 wt% Cu, 0.25 wt% Zn, 4.63 wt% As) (Table 1). These observations confirm the fact that heavy metals such as Pb, Cu or Zn can concentrate in HFO by adsorption/co-precipitation effects [2,22]. Similarly, arsenic shows a strong tendency for adsorption onto HFO in acidic conditions and remains fully adsorbed up to pH 6 [23,27]. It was reported that Pb and Cu are adsorbed on the HFO surface at a lower pH than Zn [2,7]. Taking into account significantly no or very low Zn concentrations compared to other toxic metals and metalloids, the HFO filling fractures and cavities probably precipitated in slightly acidic conditions (at pH∼6) (Table 1).

Copper hydroxide (Cu(OH)2) is a rare phase forming dark blue needles and spears covering the primary Cu-rich mattes (Fig. 1b). Karthikeyan et al. [20] noted that a high pH is necessary for the precipitation of hydroxides of some metals. The precipitation of Cu(OH)2 takes place on the surface of Cu-bearing primary minerals in oxidising conditions at pH>6 [13]. The presence of such a phase, uncommon in sulphide weathering environments, confirms neutral to alkaline conditions. This fact was confirmed by Eary [7], who reported that Cu(OH)2 is a soluble phase and consequently does not represent an important Cu-controlling phase in the acidic environment.

3.2.2 Sulphates

Sulphates and hydroxysulphates commonly form during the oxidation of sulphide minerals [1,16]. They act as solid-phase buffers on dissolved metal concentrations, although they have varying solubility [18]. Brochantite (Cu4(OH)6SO4) forms euhedral or platy crystals of green colour (Fig. 1e and g) and is often associated with beaverite (PbCuFe2(SO4)2(OH)6), which forms sponge-like aggregates (Fig. 1e). The association of brochantite and beaverite indicates a relatively low pH and high sulphate concentrations [21]. Alpers et al. [1] classified brochantite amongst sulphates of intermediate solubility. However, some copper patinas composed of brochantite can dissolve in extremely acid conditions as observed on buildings in the areas with high SO2 concentrations in the atmosphere [12]. Beaverite commonly crystallises together with plumbojarosite during the oxygen–sulphuric acid pressure leaching of sulphide concentrates [17]. These compounds precipitate in acidic conditions; in alkaline environments, the preferential precipitation of other iron compounds (e.g., Fe(OH)3) takes places [17]. Alpers et al. [1] noted that beaverite, a member of alunite group, counts amongst less-soluble sulphates and will probably represent an efficient solubility-controlling phase for Cu (and Pb).

Jarosite (KFe3(SO4)2(OH)6) forms platy irregular crystals (Fig. 1f). The presence of jarosite clearly indicates acidic conditions (pH<3) [6]. The potassium supply probably originates from the selective dissolution of nearby silicate slag, which is dumped together with mattes [8]. Jarosite tends to dissolve at pH>3, releasing sulphate ions and Fe3+ into the solution. As pH rises, the transformation of jarosite into hydrous ferric oxides such as goethite takes place [6].

Thenardite (Na2SO4) is a rare phase. It was found as small white–yellow rounded crystals on the surface of some mattes (Fig. 1h). Its presence was already mentioned by Jambor [16] in coal wastes. As for jarosite, the dissolution of nearby slag glass dumped together with mattes [8] likely provides a sufficient amount of Na. Gypsum (CaSO4·2 H2O) is a common phase in oxidised zones of sulphide-rich mine tailings or coal wastes [16]. As an alteration product of metallurgical mattes, it probably forms in environments where Ca2+ and SO42− supplies by alteration of silicate slag and by sulphides oxidation are sufficient enough [8]. Gypsum commonly occurs as efflorescences even at calcium-poor substrates, e.g., clay-rich sandstones [26], and therefore its crystallisation can also be related to the direct evaporation of rainwater. On the surface of matte, gypsum commonly forms well-shaped individual crystals up to several hundreds of microns in length (Fig. 1d). Thenardite and gypsum are soluble sulphates and their dissolution leads to a significant release of sulphate ions into the solution [1].

3.2.3 Carbonates

Carbonates are common alteration products in environments characterised by a higher CO2 pressure and neutral to alkaline conditions [1,7,28]. Cerussite (PbCO3) forms platy crystals (Fig. 1i) similar to those observed on the surface of weathered PbZn metallurgical slags [9,11]. In general, it is associated with metallic lead (Fig. 1i) and likely precipitates in neutral or alkaline environments with sufficient CO2 supply from the atmosphere.

Malachite (Cu2(OH)2CO3) was observed on the matte surface as green reniform aggregates composed of submicroscopic spears and laths (Fig. 1c). The thermodynamic study of the CuH2OCO2 system showed that malachite is stable at pH>5 [24]. Eary [7] noted that malachite represented an important Cu-scavenging phase in carbonate-rich waters at pH>7.5.

Powder diffraction patterns (JCPDS–ICDD card 37–0501, [15]) identified a rare compound of chemical composition NaOH·2 PbCO3. It forms white to pale-blue crusts and was observed on the same samples as the copper hydroxide (see above). The compound NaOH·2 PbCO3 prepared by Brooker et al. [3] precipitated in alkaline conditions (pH 11) as a reaction product of cerussite (PbCO3) and 0.1 M Na2CO3 solution. Thus, the presence of such a compound (as well as that of copper hydroxide) confirms strongly alkaline conditions, which can exist on the surface of some mattes.

3.3 Environmental issues

In oxidised environments, sulphides tend to liberate metallic ions and sulphate ions into the water [25]. When submitted to atmospheric alteration, sulphide mattes from the lead smelting will undergo a similar weathering process. The role of the dissolution kinetics and the salinity of altering solutions within unsaturated zones in the dumps are actually difficult to determine. Nevertheless, the description of alteration products helps to determine the basic dissolution/precipitation reactions of matte surfaces in oxidised environments. The large variety of corrosion products observed on the surface of metallurgical mattes indicates a wide pH range and shows that different conditions can be found in their free-atmosphere disposals. Fig. 3 shows the approximate pH-dependent stabilities of observed matte corrosion products in oxidised environments. However, it must be noted that the real stability is strictly related to a large number of other parameters (partial pressure of CO2, activities of metallic ions and SO42−…). Some of the secondary phases, such as jarosite, form in significantly acidic conditions and are stable exclusively at low pH (Fig. 3). Other phases precipitate rather in neutral and alkaline conditions (carbonates, copper hydroxide) (Fig. 3). The presence of some very soluble phases (such as some metallic sulphates) represents a severe risk for ecosystems; a change in pH–Eh conditions or wetting events can induce the dissolution and subsequent liberation of metallic ions and sulphate ions into the surface or ground waters [1]. On the other hand, the adsorption to and the co-precipitation with newly formed hydrous ferric oxides represent an efficient controlling mechanism for some heavy metals and metalloids (see Table 1, [1,7]).

As a result, it is evident that the definition of the best dumping conditions for such a complex material is extremely difficult. A free-air scenario proposed by Ettler et al. [11] for the dumping of metallurgical slags cannot be applied for mattes. If the latter are not reused in subsequent metallurgical processes (e.g., for copper recovery from mattes in Cu-smelting plants), they should be dumped in a controlled waste-disposal site. Their dumping in reducing environments may be also taken into account [25]. The technological barriers such as organic material or impermeable clay layers, which are frequently utilised for mine tailings or acid mine drainage effluents, could possibly be applied for matte disposal sites in order to reduce the oxygen supply and thus the subsequent alteration of sulphide phases [4,19].

Acknowledgements

This study was financed by research project GP205/01/D132 of the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic, projects from the Charles University (J13/98:113100005) and the Ministry of Education (LN00A028). The authors thank Zdeněk Kunický, Technical Director of the Přı́bram smelter (Kovohutě Přı́bram) for facilitating sampling on the dumps and for fruitful discussions. Annick Genty (SEM/EDS), Christian Gilles (EMPA) and Petr Bezdička (XRD) assisted during the analytical work. Viktor Goliáš (Charles University) is thanked for three diffraction patterns performed by the Debye–Scherrer technique.