Version française abrégée

1 Introduction

Les impacts météoritiques ont joué un rôle essentiel dans l'histoire de la Terre [16,25]. Cependant, la plupart des astroblèmes ont été effacés par le volcanisme, la tectonique et l'érosion. Il existe actuellement plus de 160 cratères d'impact reconnus [9] et on estime que seulement 10 % des astroblèmes d'un diamètre supérieur à 10 km et âgés de moins de 100 Ma sont connus [8].

Le Sahara compte parmi les régions les plus favorables à la préservation des cratères d'impact et l'on recense actuellement 17 astroblèmes en Afrique [11,28]. Alors que l'exploration de grandes étendues à l'aide de techniques géophysiques classiques reste limitée, l'usage de l'imagerie spatiale permet d'ausculter facilement de vastes régions. L'utilisation de capteurs optiques classiques ne donne accès qu'à la couverture de surface du désert ; en revanche, le radar à ouverture de synthèse (ROS) permet d'imager les premiers mètres du sous-sol [4], comme cela a été démontré dans le désert Egyptien à l'aide de données SIR-A [14].

2 Cartographie étendue à partir de radars orbitaux

Les missions orbitales radar ont produit à ce jour des couvertures partielles des régions désertiques, à l'exception de la plate-forme JERS-1 de l'agence spatiale japonaise (NASDA). Nous avons réalisé, dans un premier temps, une mosaı̈que radar en bande L du Sahara oriental à une résolution de 50 m [20], qui sera suivie dans une seconde phase par une mosaı̈que complète du Sahara et de la péninsule arabique à partir du satellite ALOS de la NASDA qui sera lancé en 2004. Notre première mosaı̈que radar a permis de révéler deux structures circulaires dans le Sud-Est de la Libye, structures qui pourraient être le résultat d'impacts météoritiques. Nous présentons dans la suite les résultats d'une campagne de terrain, qui confirment cette hypothèse.

3 Astroblèmes connus dans le Sahara oriental

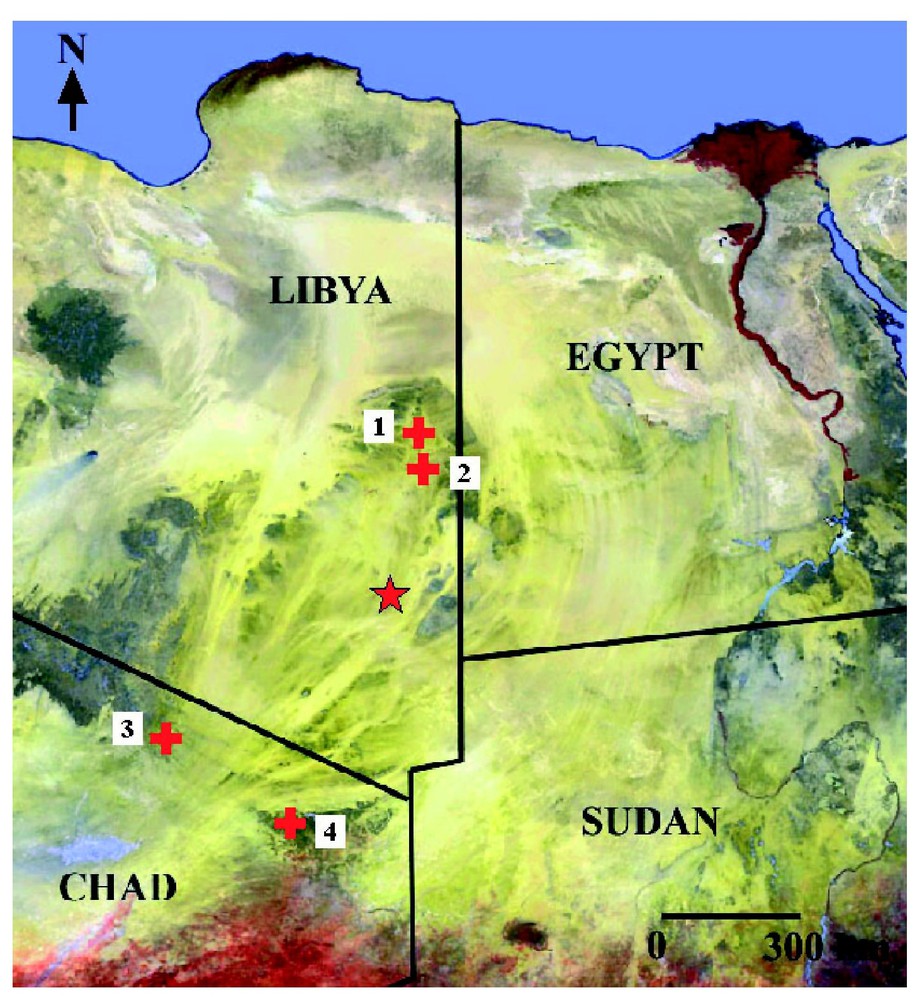

Seuls quatre cratères d'impact sont actuellement reconnus dans le Sahara oriental, deux localisés en Libye et deux au Tchad.

BP (N25°19′, E24°20′) a été découvert par Martin [13] et présente deux anneaux d'un diamètre maximum de 3 km. L'impact s'est produit dans un grès nubien du Crétacé inférieur et est âgé de moins de 120 Ma. Oasis (N24°35′, E24°24′) a un diamètre de 18 km et présente un anneau central de 5 km [6]. Il est aussi localisé dans les grès nubiens et son âge est également estimé à moins de 120 Ma. Ces deux cratères d'impact pourraient être associés avec les verres libyens trouvés à proximité [1]. Gweni-Fada (N17°25′, E21°45′) est un cratère complexe d'un diamètre de 14 km présentant un soulèvement central [27]. On le situe dans des grès du Dévonien et son âge est de moins de 350 Ma [17]. Enfin, Aorounga (N19°06′, E19°15′) est une dépression circulaire de 12 km de diamètre, observée initialement par Roland [21] et confirmée ensuite comme impact [2]. Il est situé dans un grès fin du Dévonien supérieur et est âgé de moins de 350 Ma [11]. Il présente une structure de doubles anneaux séparés par une dépression sableuse. Il a été observé par le radar de la mission SIR-C [15] et pourrait faire partie d'un impact multiple [18].

4 Les nouvelles structures circulaires observées par JERS-1 et LANDSAT 7

Les nouvelles structures découvertes sont localisées à 110 km à l'ouest de Djebel Arkenu et à 250 km au sud de l'oasis de Koufra, au point de coordonnées N22°04′, E23°45′ (cf. Fig. 1). C'est une région plane et hyper-aride, présentant une formation de grès du Crétacé, recouverte par des dépôts éoliens du Quaternaire.

Known impact craters in East Sahara on a Spot Vegetation image. (1) B.P., (2) Oasis, (3) Aorounga, (4) Gweni-Fada. The star indicates the position of the discovered double structure.

Cratères d'impacts connus au Sahara Oriental visualisés sur une image Spot Végétation. (1) B.P., (2) Oasis, (3) Aorounga, (4) Gweni-Fada. L'étoile indique la position de la structure double découverte.

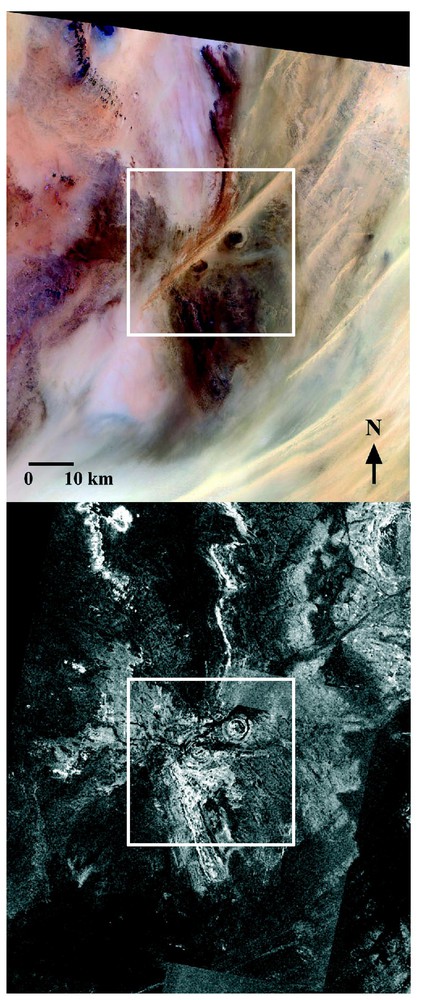

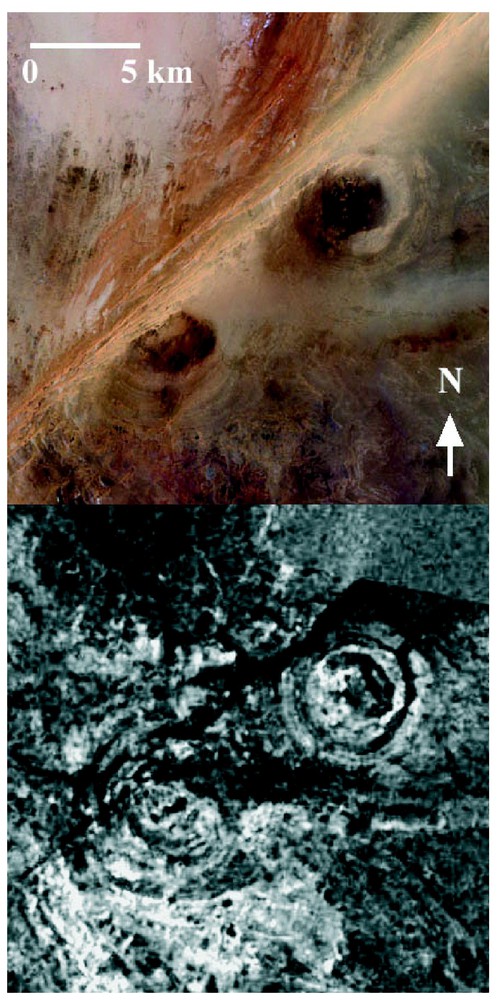

La Fig. 2 montre une image satellite Landsat 7 et une scène radar JERS-1 de la région, les deux structures circulaires étant clairement révélées par l'image radar. La Fig. 3 montre le site à une résolution de 50 m, le radar permettant d'identifier un premier cratère au sud-ouest, d'un diamètre de 10,3 km, accolé à un second cratère au nord-est, d'un diamètre de 6,8 km. Le cratère nord-est est composé de deux anneaux séparés par une dépression remplie de sédiments et présente une morphologie très semblable à l'astroblème d'Aorounga au Tchad. Le cratère sud-ouest présente également une forme circulaire avec, semble-t-il, trois anneaux concentriques. Les structures sont localisées dans un grès grossier à conglomérats du Crétacé inférieur [7], impliquant que l'impact serait, au plus, âgé de 140 Ma.

Landsat 7 ETM+ optical image (top) and extract of the JERS-1 L-band radar mosaic (bottom). The double circular structure is located at the center of the images.

Image optique Landsat 7 ETM+ (haut) et extrait de la mosaı̈que radar en bande L JERS-1 (bas). La structure circulaire double est au centre des images.

Landsat 7 ETM+ image of the double circular structure (top), and the corresponding JERS-1 L-band radar image (bottom) at a resolution of 50 m.

Image Landsat 7 ETM+ de la structure circulaire double (haut) et image radar JERS-1 en bande L correspondante (bas) à une résolution de 50 m.

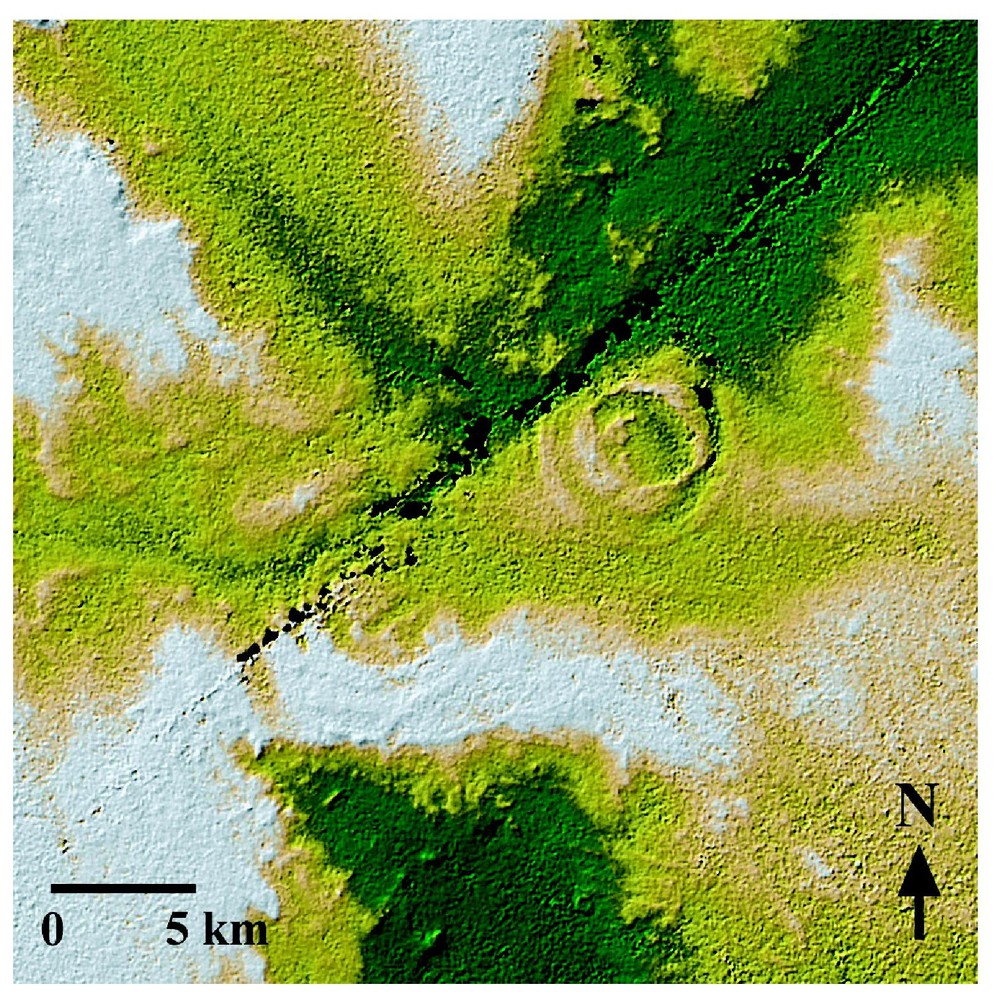

La Fig. 4 montre le relief de la région en fausses couleurs issu du modèle numérique de terrain (MNT) global produit par la mission SRTM [5]. La variation totale en élévation dans l'image est de moins de 20 m, et les bords du cratère nord-est culminent 5 à 10 m au-dessus de la plaine environnante. Les structures du cratère sud-ouest sont à peine visibles, indiquant une topographie plane.

Color-coded shaded relief image of the region, derived from the SRTM DEM (source JPL/NASA). The total elevation change in the image is less than 20 m.

Image du relief de la région en fausses couleurs issue du MNT SRTM (source JPL/NASA). La variation totale en élévation dans l'image est inférieure à 20 m.

5 Premiers résultats de la mission sur sites

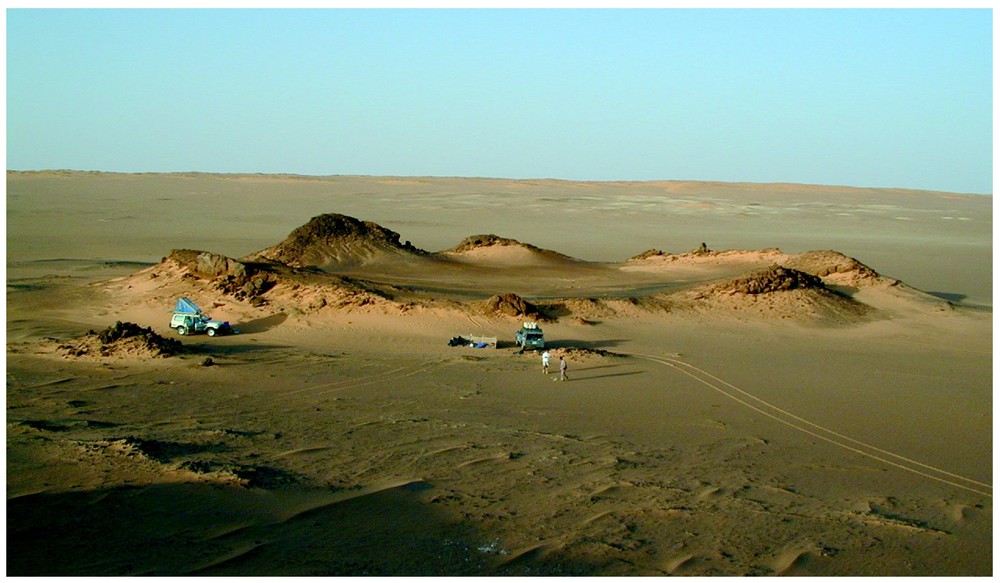

Une mission d'exploration sur sites a été réalisée en avril 2003. Comme prévu par le MNT SRTM, le paysage présente peu de relief, et on peut observer des dépôts éoliens recouvrant le grès du Crétacé (cf. Fig. 5). Les anneaux du cratère nord-est sont constitués de blocs de grès, parfois recouverts de dépôts sableux, s'élevant entre 5 et 10 m au-dessus de la plaine centrale du cratère. Les structures concentriques du cratère sud-ouest correspondent à des talus de grès sub-affleurants.

Landscape as seen from the center of the northeastern crater, facing to the northeast. Horizon corresponds to the inner ridge of the crater. The structure in the middle of the image is an outcrop of breccia close to the crater center.

Paysage vu depuis le centre du cratère nord-est, en faisant face au nord-est. L'horizon correspond à l'anneau interne du cratère. La structure au centre de l'image est un affleurement de brèches proche du centre du cratère.

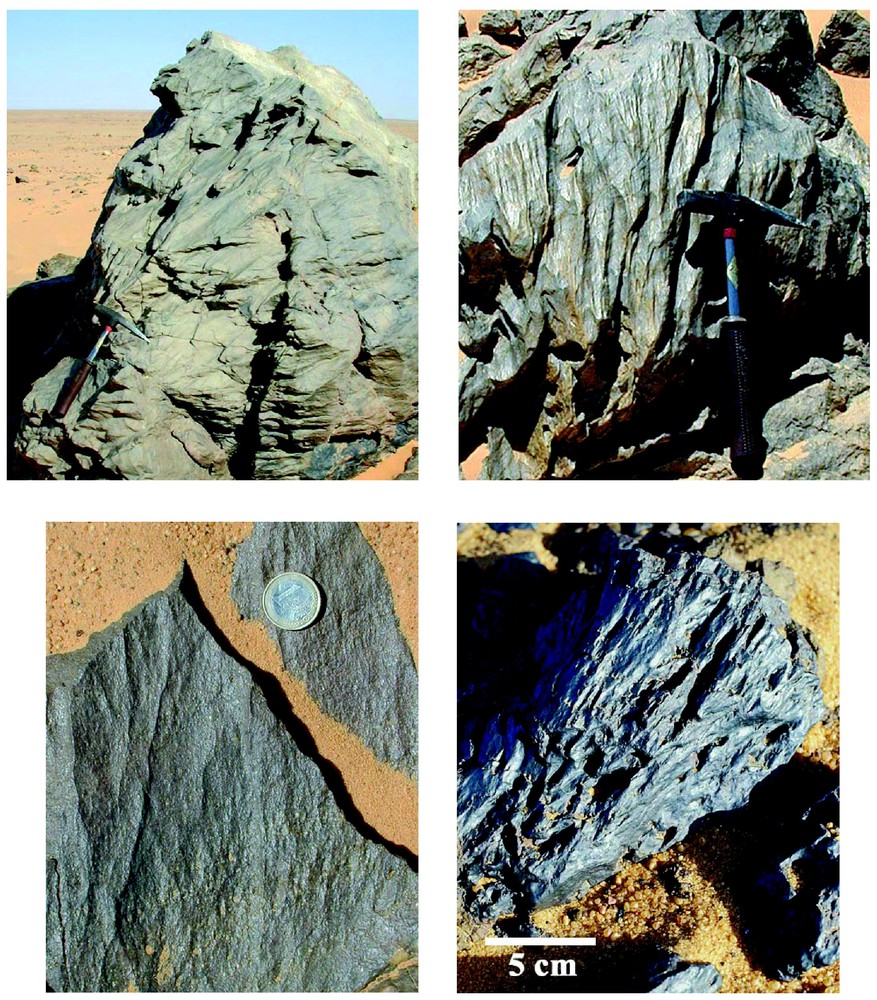

Nous avons pu observer des cônes de percussion en quantité (cf. Fig. 6), tous localisés le long de l'anneau interne du cratère nord-est. La mesure de la direction de l'axe des cônes le long de l'anneau interne du cratère montre qu'ils pointent tous vers le centre du cratère. Ceci s'explique par la cohérence à grande échelle de la fracturation primaire induite par un impact [23].

Shatter cone structures in shocked sandstone blocks along the inner ridge of the northeastern crater.

Cônes de percussion dans des blocs de grès choqués le long de l'anneau interne du cratère nord-est.

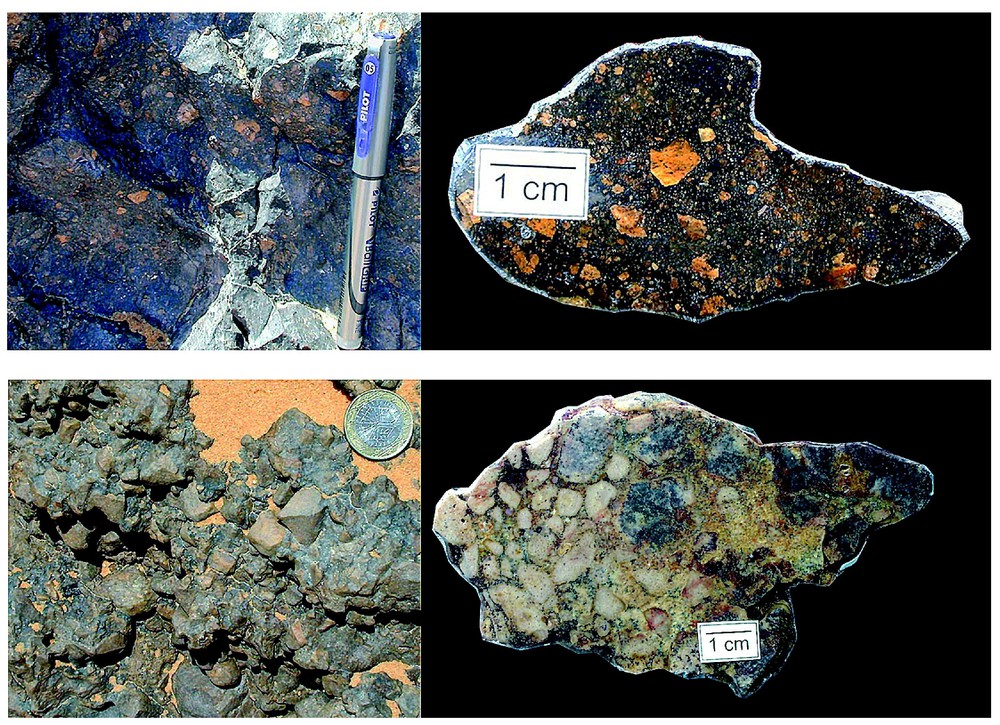

Des affleurements importants de brèches allochtones [26] ont pu être observés dans les deux cratères. Le haut de la Fig. 7 montre une suévite prélevée à proximité de l'anneau interne du cratère nord-est, à environ 1,2 km du centre. Des observations pétrographiques suggèrent qu'elle contient de grands fragments irréguliers d'anciens verres de fusion emballés dans une matrice sombre riche en oxyde de fer (Fig. 8).

Two impact breccias sampled on the site: left images present breccias in place while right images show sawed and polished surfaces. Top: impact melt breccia sampled close to the inner ridge of NE crater, about 1.2 km away from the crater center. Bottom: polymict breccia sampled about 3 km southern of the center of southwestern crater.

Deux échantillons de brèche d'impact ramassés sur site : les images de gauche présentent les brèches in situ, alors que les images de droites montrent des coupes polies. Haut : brèche de fusion prélevée à proximité de l'anneau interne du cratère nord-est, à environ 1,2 km du centre du cratère. Bas : brèche polymictique échantillonnée à environ 3 km au sud du centre du cratère sud-ouest.

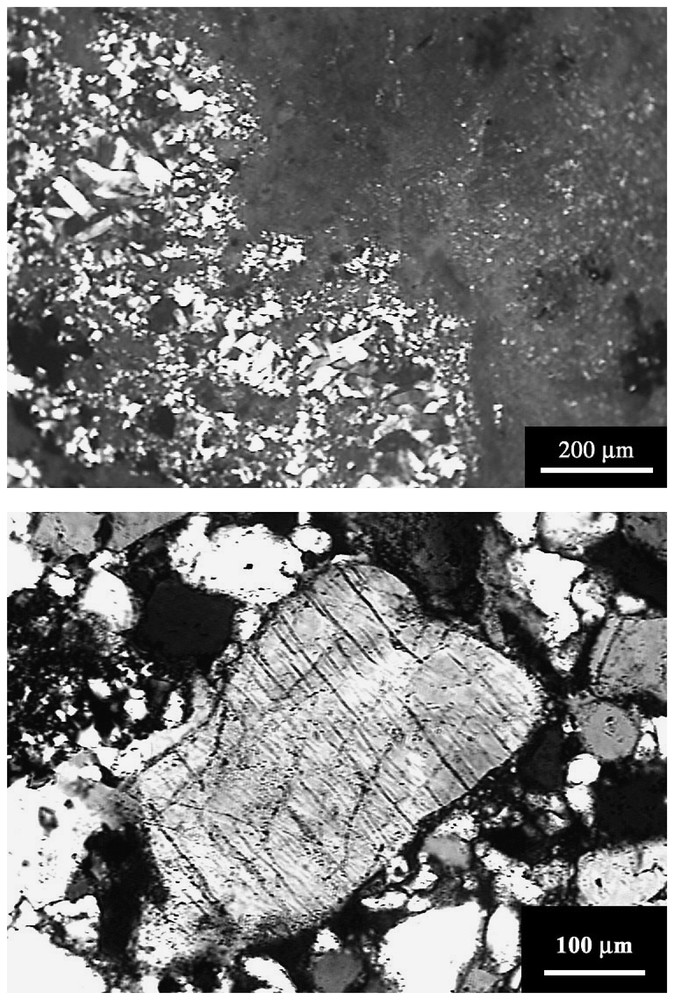

Top: photomicrograph (crossed polars) of a grain showing a subisotropic area next to a recrystallized region observed in the breccia sample presented in Fig. 7 (top). Bottom: photomicrograph (crossed polars) of PFs observed in a quartz grain from the breccia sample, presented in Fig. 7 (bottom).

Haut : photographie au microscope polarisant (polariseurs croisés) d'un grain présentant une région quasi isotrope accolée à une zone de recristallisation observé dans l'échantillon de brèche présenté Fig. 7 (en haut). Bas : photographie au microscope polarisant (polariseurs croisés) de PFs observées dans un grain de quartz de l'échantillon de brèche, présenté sur la Fig. 7 (en bas).

La partie inférieure de la Fig. 7 correspond à une brèche polymicte, qui contient des fragments de grès. Un grand nombre de structures planaires (planar fractures ou PFs) ont été observées dans cet échantillon : la Fig. 8 (en bas) montre une photographie au microscope polarisant d'un grain de quartz choqué présentant des structures planaires espacées d'environ 15 μm. De telles structures sont la signature d'effets de choc correspondant à une gamme de pression de 5 à 20 GPa [10].

Au vu des résultats de l'étude sur site, nous pouvons affirmer que les structures circulaires découvertes dans le Sud-Est de la Libye ont été formées par l'impact d'une paire de météorites d'un diamètre de l'ordre de 500 m. Nous proposons de nommer ces astroblèmes « Arkenu 1 » pour le cratère nord-est et « Arkenu 2 » pour le cratère sud-ouest.

1 Introduction

Impact cratering is now recognized as a major geological process on Earth [16]. In particular, giant impacts had a fundamental influence on the geological and biological evolution of our planet. Bodies with diameters larger than 1 km, which create impact craters larger than 10 km in diameter, collide with the Earth at a frequency of about once per 4.3×106 years [25]. Unfortunately, most impact craters have been erased from the Earth's surface due to volcanism, tectonics, erosion and deposition. Remaining structures are generally eroded and recovered by sediments. There are more than 160 confirmed impact craters on Earth [9], but it is estimated that only 10% of impact craters larger than 10 km and younger than 100 Ma are known [8], i.e. most of them are still to be discovered (e.g., [22]). The most favorable regions for finding well-preserved craters are arid deserts, such as the Sahara and the Antarctic, where very low erosion and deposition rates prevail.

There are currently 17 known impact craters in Africa, most of them located in northern or southern desert regions [11,28]. The Sahara is a particularly favorable region to host young impact craters but, according to cratering rate estimates, most of them still remain to be discovered, hidden under dry sandy sediments. As exploration of such large and arid regions by ground-based techniques is both demanding and limited to point measurements, remote sensing techniques were used to cover vast areas with high spatial resolution. While optical sensors can only image the desert's surface, it was shown twenty years ago that orbital Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) could retrieve subsurface information hidden under a few meters of dry sand [4]. In particular, radar images at L-band (1.25 GHz/24 cm) from the first Shuttle Imaging Radar experiment (SIR-A) revealed sand-buried paleodrainage channels in the southern Egyptian desert [14].

2 Regional-scale mapping using space-borne radar

While the Shuttle Imaging Radar series has demonstrated the potential of mapping subsurface structures using L-band radar, the missions were nevertheless limited in time and did not produce a full geographic coverage of the land surface. We present here the first results of an international effort – dubbed SAHARASAR – for mapping of the near subsurface of the Sahara and Arabian regions using satellite-borne L-band radar, to reveal the existence of paleohydrological networks, tectonic features, and impact craters.

As a first step, a regional-scale image mosaic at 50 m resolution over the eastern Sahara has been generated from fine resolution L-band SAR data from the Japanese Earth Resources Satellite (JERS-1) that was operated by NASDA from 1990 to 1998 [20]. The second phase will be a continuation of the mapping of the entire Sahara region and Arabian peninsula using the next-generation Japanese L-band SAR onboard the ALOS platform (due for launch in 2004), which will have improved polarimetric capabilities for scattering characterization and subsurface penetration.

As a first result using the JERS-1 mosaic over the eastern Sahara, a double circular structure has been detected in the southeastern part of the Libyan Desert. This formation is likely to be an unknown double impact crater with a diameter around 10 km, and we present here field observations and shock metamorphism evidences that support this hypothesis.

3 Known impact craters in eastern Sahara

Only four confirmed impact craters are currently known in eastern Sahara. Two are located in eastern Libya: B.P. (British Petroleum) structure and Oasis crater, and two are located in northern Chad: Aorounga and Gweni-Fada craters (Fig. 1). Confirmations of an impact origin for these craters are: Planar deformation features (PDFs) in quartz at B.P. and Oasis [6], PDFs in quartz at Gweni-Fada [27], and shatter cones and PDFs in quartz at Aorounga [2].

The B.P. structure (N25°19′, E24°20′) was first discovered by Martin [13] and consists of two eroded and discontinuous annular ridges of hills, with a diameter of about 3 km. Shocked rocks are from the Early Cretaceous Nubian sandstone formation, and the impact is younger than 120 Ma [11].

Oasis (N24°35′, E24°24′) has a diameter of 18 km, with a 5 km in diameter central annular ridge surrounded by an annular depression [6]. It is also located in the Nubian sandstone formation, and its age is also estimated to be less than 120 Ma. These two craters could be associated with the occurrence of the Libyan Desert glass found in the neighborhood [1].

Gweni-Fada (N17°25′, E21°45′) is a complex crater 14 km in diameter, with a pronounced central uplift. It was first recognized through the study of aerial photos, and its impact origin was later confirmed by fieldwork [27]. The target rocks are Devonian sandstones and the impact age is less than 350 Ma [12,17].

Aorounga (N19°06′, E19°15′) is a nearly circular depression with a diameter of 12.5 km, which was first observed by Roland [21] and later confirmed as an impact crater [2]. The host rock of the crater is a fine-grained sandstone of Upper Devonian age containing plant fossils, and the crater age is estimated at less than 350 Ma [11]. The structure consists of two concentric ridges, rising 100 m above the surrounding plain, separated by a depression. It was observed by the orbital radar of the SIR-C experiment [15] and could have formed as part of a multiple impact event, as at least another crater-like structure appears to the northeast of the Aorounga crater [18].

4 New circular structures observed by JERS-1 and LANDSAT 7

The newly discovered structures are located 110 km west of Djebel Arkenu and 250 km south of Kufra oasis in Libya, at coordinates N22°04′, E23°45′. It is a flat and hyperarid area, presenting a Cretaceous sandstone formation covered by active Aeolian deposits and Quaternary soils, located tens of kilometers away from any track, in a hazardous zone due to the proximity of Second World War minefields. Satellite images of the region are presented in Fig. 2. The optical Landsat 7 image (top of Fig. 2) shows a sandy region with large sand dunes trending SW-NE, while the corresponding L-band radar image extracted from the JERS-1 radar mosaic (bottom of Fig. 2) reveals two circular structures partially hidden by Quaternary deposits.

Fig. 3 shows an enlargement of the images in Fig. 2 at a resolution of 50 m. The radar scene clearly reveals a double circular structure composed of a southwestern crater 10.3 km in diameter and a northeastern crater of diameter 6.8 km. The northeastern crater is composed of concentric inner and outer rings separated by a depression filled with sediments, also observed in the optical scene (Fig. 3, top). Its morphology is very similar to the Aorounga crater in Chad, corresponding to a typical complex crater. The southwestern crater also presents a circular shape with possibly three concentric annular ridges.

The optical Landsat image barely reveals the outer parts of the craters because of the sand cover, but clearly shows the center of both craters as depressions filled with darker sediments. Considering a penetration depth of about one meter for L-band signals in dry sandy sediments [19,24] leads to the conclusion that the outer ridge walls of the two craters are exposed at the surface, or are at most covered by a few centimeters of dry sand. The host rock of the double circular structure is a cross-bedded coarse-grained to conglomeratic sandstone of Lower Cretaceous age containing plant fossils and thin shale interbeds [7], leading to an estimated impact age of less than 140 Ma. Fig. 2 (bottom) shows that the proposed impact zone is surrounded by a region of bright radar response, especially to the southwest of the southwestern crater. It corresponds to a rougher surface than the surrounding sandy plains [3], correlated to the darker sandstone formation visible in the corresponding optical image (Fig. 2 top).

Finally, Fig. 4 presents a color-coded shaded relief image of the region, derived from the Digital Elevation Model (DEM) obtained by the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) [5]. Black patches are voids, where the radar signal was too low to allow an elevation value to be derived, and correspond to the large sand dune observed in the Landsat image of Fig. 3 (top). The total relief in the DEM is less than 20 m. The northeastern crater ridges (brown-white color in Fig. 4) rise 5 to 10 m above the surrounding plains (yellow color in Fig. 4). The southwestern crater rims are hardly visible, the DEM confirming that this circular structure is almost completely flat and covered by sandy sediments: only the subsurface imaging capabilities of the L-band SAR could clearly reveal the buried structures.

5 First results of fieldwork investigations

A field survey was carried out during April 2003 in order to obtain definitive proof of the impact origin of the observed structures (i.e. shatter cones, high shock pressure metamorphism, planar microstructures in quartz grains, high pressure polymorphs such as coesite and stishovite, iridium enrichment).

As expected from the SRTM DEM, the landscape at the site is flat and mainly presents Aeolian sandy deposits and Cretaceous sandstone (cf. Fig. 5). The inner and outer ridges of NE crater are made of sandstone blocks, covered at some places by a superficial sand sheet of Aeolian sediments. We could confirm that the annular ridges rise 5 to 10 m above the crater center. The southwestern crater presents much smoother ridges that appear on the field as flat sandstone outcrops. As observed on Landsat images, both crater centers are covered with darker sandy sediments.

We observed quantities of shatter cone structures on the site (cf. Fig. 6), all located close to the inner ridge of the northeastern crater. Fig. 6 (top left) shows in particular a big sandstone block presenting fully developed cones. We regularly measured the orientation of the shatter cone axes along the southeastern part of the inner ridge of the northeastern crater, and observed that they all point towards the crater center. This can be explained by the large-scale geometry induced by the primary tensile fractures produced by an impact event [23].

Quantities of allochthonous impact breccia outcrops [26] could be observed in both craters. Top of Fig. 7 shows one of these outcrops and a polished sample collected close to the inner ridge of NE crater, about 1.2 km away from its center. The yellowish fragments, embedded in an iron oxide-rich dark matrix, exhibit subisotropic regions consisting in submicron grains and recrystallised areas with 10 to 50 μm elongated and undeformed feldspars (Fig. 8, top). These textures suggest a recrystallisation after partial amorphization or melting during the impact: the breccia in Fig. 7 (top) is then very likely to be a suevite. Bottom part of Fig. 7 presents a polymict impact breccia containing angular sandstone fragments. Quantities of planar fractures (PFs) could be observed in this sample: Fig. 8 (bottom) shows a photomicrograph (crossed polars) of a quartz grain exhibiting clear parallel PFs with a spacing of about 15 μm. Such regular planar microstructures are diagnostic shock effects in a pressure range from 5 to 20 GPa, although this range is harder to define when dealing with sedimentary rocks [10].

From our field study, i.e. observation of shatter cones and discovery of impact breccias, we can assert that the newly discovered circular structures were produced by the impact of a 500 m diameter pair of asteroids. Because of the proximity of Djebel Arkenu, we propose to name the two new impact craters as follows: ‘Arkenu 1’ for the northeastern crater and ‘Arkenu 2’ for the southwestern crater.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank M. Kobrick of NASA/JPL for providing the color-coded shaded DEM and C. Odon of ‘Terre d'Origine’ for fieldwork support. They are also grateful to R.A. Grieve, A. Therriault, P.-M. Vincent and J.-F. Becq-Giraudon for their very valuable advises. This work was financially supported by the French ACI for Earth Observation.