Version française abrégée

1 Introduction

Le golfe de Corinthe (Grèce continentale) est actuellement une des régions parmi les plus actives sur le plan sismique en Europe. Cette activité sismique est à mettre en liaison directe avec le contexte tectonique de la région. La partie sud du golfe de Corinthe est un lieu privilégié d'observation des relations entre une tectonique active récente et la sédimentation associée [17]. La région est découpée en blocs successifs par une série de failles normales globalement orientées est–ouest (Fig. 1). Dans les blocs délimités par ces failles majeures se sont majoritairement développés des édifices de type Gilbert-delta. L'architecture et la sédimentologie de ces corps ont déjà fait l'objet de nombreux travaux [1,3,12,13,16]. Néanmoins, peu de données biostratigraphiques fiables ont été jusqu'à présent publiées. Selon les auteurs et selon les lieux d'étude, les âges de la série syn-rift varient du Miocène à l'Holocène [1,3,12–15].

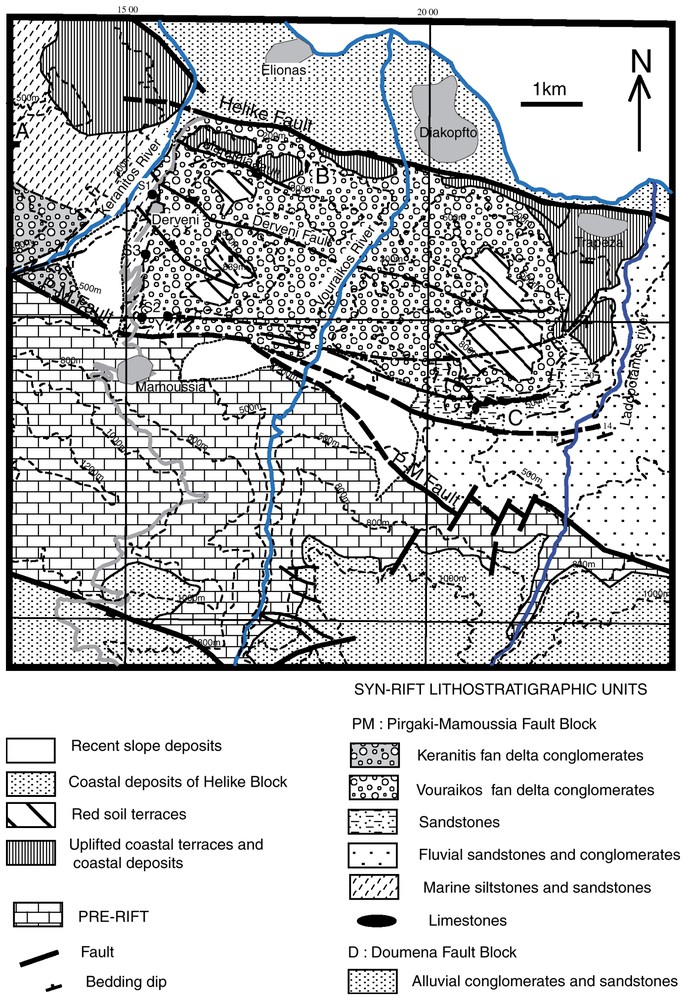

Geological map of the Pirgaki–Mamoussia fault block and part of the Doumena fault block to the south between the Kerinitis and Ladopotamos Rivers, comprising principally the Vouraikos fan delta conglomerates. The photographs shown in Fig. 2 were taken looking east from locality A. B is the location of marine limestones within the Vouraikos conglomerate succession. At C, fine-grained white limestones occur within the sandstone and conglomerate succession below the Vouraikos conglomerates. S1 to S3 are the localities of biostratigraphical samples, all giving Early-Pleistocene ages. Topographic contours at 200, 500, 800, 1000 and 1200 m are shown. Villages and towns are shown in grey.

Carte géologique du compartiment faillé de Pirgaki–Mamoussia, montrant le développement du fan delta de Vouraikos. La localisation du panorama de la Fig. 2 et la position des échantillons cités dans le texte sont indiquées.

Nous présentons ici les résultats préliminaires concernant le Gilbert-delta de Vouraikos, en termes de biostratigraphie, sédimentologie de faciès, et tectonique associée. Les résultats permettent de préciser l'évolution géodynamique du golfe de Corinthe dans ce secteur.

2 Contexte de l'étude

Le Gilbert-delta de Vouraikos affleure sur une surface d'environ 40 km2, entre la faille normale, récente et active, d'Helike, au nord, et la faille normale de Pirgaki–Mamoussia, au sud (Fig. 1). Le substratum de la série syn-rift est constitué par la série pré-rift, composée principalement de carbonates (Trias–Jurassique) et de flyschs (Crétacé), qui ont été tectonisés à la fin du Mésozoı̈que et au début du Cénozoı̈que pendant l'orogenèse hellénique. L'édifice deltaı̈que se met en place sur une épaisse série fluviatile, bien visible dans la vallée de Ladopotamos (Fig. 1). La localisation du delta de Vouraikos, ainsi que d'autres édifices du même type sur l'ensemble de la région, semble gouvernée par le jeu de failles normales (Figs. 2 et 3). La partie frontale du delta est incisée par des terrasses marines (Figs. 1 et 3) datées du Pléistocène supérieur [4]. Le sommet de l'édifice est occupé par des sols rouges, bien représentés sur le plateau d'Asomati (Figs. 1 et 2).

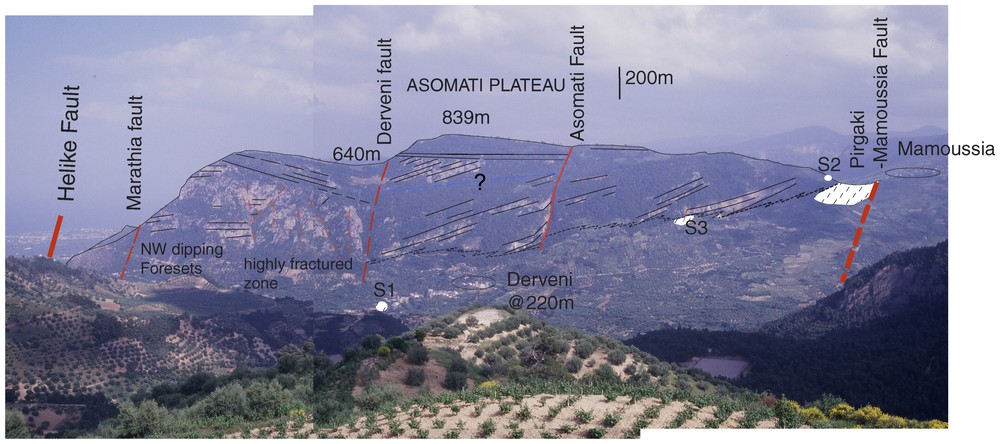

View eastward across the Kerinitis River valley to the western cliffs of the Asomati plateau (locations from which photographs were taken are shown in Fig. 1). The cliffs are formed by conglomerates of the Vouraikos fan, organised in north and northwest-dipping foresets. These foresets pass downward into bottomset and pro-delta facies (oblique dashed pattern). The diachronous base of the deltaic conglomerates dips gently northward. Topsets are visible at the top of the succession. The topmost surface is a red soil terrace displaced and tilted southward by the Derveni and Asomati faults. S1 to S3 are the localities of biostratigraphical samples.

Panorama de la vallée Kerinitis, montrant le flanc occidental du plateau Asomati. La falaise est formée par les conglomérats du fan delta de Vouraikos. Les foresets passent tangentiellement, à la base de la photo, aux bottomsets et aux faciès de prodelta. Le toit de l'édifice est occupé par des sols rouges horizontaux décalés par les failles de Derveni et Asomati.

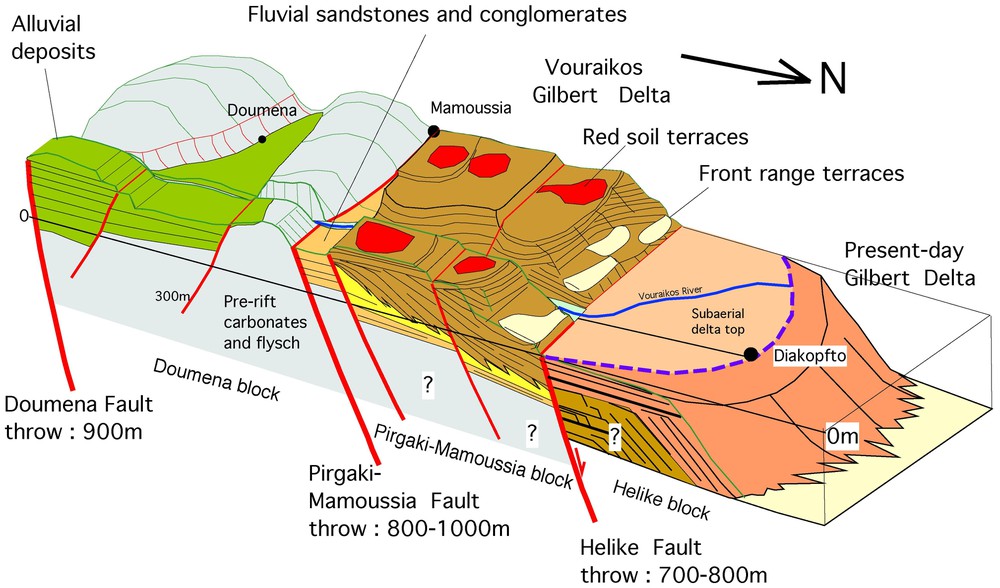

Block diagram model of the Doumena, Pirgaki–Mamoussia and Helike fault blocks viewed toward the southwest. This figure illustrates the problem of correlating syn-rift stratigraphy between the three fault blocks. Subsurface stratigraphy of the Diakopfto delta is purely conjectural.

Bloc diagramme schématique montrant le découpage et le remplissage des blocs selon un transect nord–sud. Cette figure illustre le problème des corrélations entre les dépôts syn-rifts de chaque bloc.

3 Biostratigraphie et paléoenvironnement

Dans l'ensemble du golfe de Corinthe, une difficulté majeure pour l'interprétation des séries conglomératiques de type Gilbert-delta est le manque de données biostratigraphiques. De nombreux auteurs ont proposé des âges s'étendant du Miocène à l'Holocène. Les résultats biostratigraphiques que nous présentons ici s'appuient sur une analyse palynologique d'échantillons prélevés avec un contrôle sédimentologique (localisation sur les Figs. 1 et 2).

Les associations palynologiques reconnues indiquent un âge Pléistocène inférieur : faiblesse des Taxiodaceae, présence de Liquidambar, Zelkova, Cathaya, Carya, Tsuga, Tricolporopollenites sibiricum, abondance de Cedrus (J.-P. Suc, comm. pers., 2003). La forte proportion des pollens à ballonnets (Gymnospermes) traduit un apport de type fluviatile. On trouve quelques très rares dinokystes. Les proportions de phytoclastes oxydés varient de manière importante d'un échantillon à l'autre. Cette oxydation souligne un séjour dans un milieu agité et oxygéné.

4 Associations de faciès sédimentaires : description et interprétation

Cinq associations de faciès ont pu être reconnues à l'intérieur du Gilbert-delta de Vouraikos.

(1) L'association de faciès des sommets de clinoformes (topsets) est caractérisée par la prédominance de conglomérats massifs à stratification oblique ou horizontale fruste, et de sables rouges. La texture et la géométrie de ces conglomérats et sables peuvent être mises en relation avec des systèmes de rivières à faible sinuosité migrant sur le sommet du delta. Localement, des faciès plus fins (majoritairement des siltites) présentent des horizons peu développés de paléosols carbonatés.

(2) L'association de faciès côtiers montre des conglomérats à géométrie et texture beaucoup mieux organisées. Ils présentent des stratifications parallèles horizontales ou à angle faible. Les faciès plus fins sont représentés par des sables à lamination parallèle et localement bioturbés, voire par des siltites coquillières. Ces faciès sont à rapprocher d'environnements de plage et d'avant-plage pour les sables et conglomérats et de lagon à épisodes de débordement pour les faciès plus fins. De véritables carbonates marins à texture grainstone–rudstone se rencontrent en association avec les conqlomérats et représentent des faciès de faible profondeur et haute énergie. Aucun horizon à coraux, comme ceux décrits dans la région de Xylokastro [2] n'a été reconnu.

(3) L'association des faciès de talus de progradation (foresets) de Gilbert-delta est constituée par des conglomérats et des sables grossiers bien stratifiés. Les foresets présentent une géométrie clinoforme, avec des pendages de l'ordre de 20 à 30°, tangents à la base. Cette association de faciès est volumétriquement la plus importante au sein de l'édifice deltaı̈que. Elle correspond à un dépôt par traction et/ou par écoulement en masse. L'épaisseur des faisceaux de foresets indique une profondeur d'au moins 300 à 400 m.

(4) L'association des faciès de pied de clinoforme (bottomsets) est caractérisée par des sables à rides de courant et des conglomérats à litage horizontal. Les faciès les plus fins présentent souvent des figures de déformation syn-sédimentaire (slumps et/ou figures de liquéfaction). Ils représentent la base des foresets, avec des pendages de moins de 10°.

(5) L'association des faciès de prodelta est représentée par des sables fins et des siltites massifs ou à laminations horizontales. Des graviers dispersés dans ces faciès fins sont souvent présents. L'ensemble de ces dépôts représente les faciès les plus profonds et reflète une alternance entre des processus de décantation et de courant de turbidité.

5 Géométrie externe du Gilbert-delta de Vouraikos

Dans l'axe de la structure du Gilbert-delta de Vouraikos, au moins 800 m de faciès conglomératiques sont préservés. L'architecture interne du delta est complexe et composite. Il est formé d'édifices élémentaires empilés les uns sur les autres, dont les pendages des foresets varient entre 10 et 30° et dont la direction de progradation s'étale du nord–est sur le bord oriental au NW/WNW sur le bord occidental (Figs. 2 et 3). Des basculements tectoniques en liaison avec les failles normales et/ou le soulèvement régional compliquent la structure d'ensemble. Des failles secondaires, délimitant de petits blocs à l'intérieur de l'unité structurale de Pirgaki–Mamoussia, permettent d'expliquer des basculements vers le sud au niveau du plateau d'Asomati.

À Mamoussia, la base du delta est située à 600 m d'altitude. Au niveau des gorges de la rivière Vouraikos, la base du delta est sous 200 m et, quelques kilomètres plus à l'est, la base se retrouve de nouveau à 600 m d'altitude. En l'absence d'accidents tectoniques, ceci suggère une forme concave de la base de l'édifice en coupe transversale. En effet, sur le secteur d'étude, aucune faille transverse permettant d'expliquer les variations d'altitude du contact basal n'a pu être détectée.

6 Extension et failles normales

L'accommodation nécessaire à l'installation d'édifices de type Gilbert-delta est engendrée par des variations du niveau de base sous l'effet conjugué de l'eustatisme et de la tectonique [3,9,19]. De nombreuses études ont traité de la géométrie et de la cinématique des failles normales du golfe de Corinthe [5,7,8,11]. Les failles normales majeures (Aigion, Helike, Pirgaki–Mamoussia, Doumena) présentent des déplacements verticaux compris entre 500 et 1000 m [7]. L'accommodation du delta de Vouraikos, comme pour celui de Kerinitis situé plus à l'ouest, est due au jeu de la faille de Pirgaki–Mamoussia, dont le déplacement a été estimé à 800–1000 m [11]. Le bloc faillé est lui-même découpé par des failles mineures à jeu syn- à post-sédimentaire.

7 Conclusions

(1) Les analyses palynologiques permettent de dire que le développement du Gilbert-delta de Vouraikos s'est effectué durant le Pléistocène inférieur. Ceci indique un fort taux de sédimentation associé à un soulèvement rapide du bloc de Pirgaki–Mamoussia.

(2) La découverte de calcaires marins interstratifiés dans la série conglomératique indique que ce système deltaı̈que s'est construit dans un milieu marin.

(3) L'orientation des foresets, des paléocourants, ainsi que l'organisation des faciès montrent que la dispersion des sédiments se faisait du sud vers le nord, avec une progradation deltaı̈que entre le nord–ouest et le nord–est, c'est-à-dire selon une direction orthogonale aux failles majeures limitant les blocs faillés.

(4) Le Gilbert-delta de Vouraikos présente une base concave en coupe transversale.

(5) L'accommodation nécessaire au développement du Gilbert-delta de Vouraikos fut créée par un déplacement vertical de l'ordre de 1000 m le long de la faille majeure de Pirgaki–Mamoussia. Le bloc faillé est lui-même découpé par des failles mineures à jeu syn- à post-sédimentaire.

1 Introduction

A series of large gravel-dominated fan delta sequences is preserved in normal fault blocks along the southern coast of the Gulf of Corinth between Patras and Kiato (northern Peloponnesus, Greece). The remarkable exposures of these ancient Gilbert-type fan deltas are mainly due to rapid surface uplift of the south coast [17] and incision by northward-draining rivers that cut through the sedimentary pile in a series of deep gorges. Modern gravelly fan deltas actively build into the Gulf of Corinth from an active normal fault system that defines the range front and the modern coastal plain (Fig. 1). For example, at the small town of Diakopfto, located on the modern coastal plain, a recent fan delta builds and downlaps northwards into the present-day Gulf of Corinth. The visible subaerial part of this modern fan delta combined with offshore shallow seismic profiles [18] provide a good representation of the general architecture, sedimentary environments and facies development of this kind of sedimentary system.

The two-dimensional architecture and sedimentology of several fan deltas and their relationships to the normal faults have been described by a number of workers, including Ori [12], Collier [1], Ori et al. [13], Seger and Alexander [16], and Dart et al. [3]. These superb exposures have been used to study the influence of various parameters (eustasy, tectonic movements, initial depth, sediment supply) on coastal systems, either qualitatively [13] or using computer models [6,9,19].

Little detailed sedimentological or structural work, however, has been done on one prominent Gilbert fan delta, the Vouraikos fan delta [3,15]. In addition, and despite very good exposure and accessibility of the outcrops, little biostratigraphical data have yet been published on the age of the different fan deltas; their age has therefore been disputed, with opinion ranging from Miocene to Holocene ages [1,3,12,13,15]. No study to date has resolved the water salinity of the basin into which these fan deltas were constructed.

In this short paper, we present preliminary results from a study of the 3D architecture of the Vouraikos fan delta, and provide the first biostratigraphical data from the succession associated with this system. We also detail the extensional fault systems that affected the Vouraikos fan.

2 General setting: location, faulting and morphology

The Vouraikos fan delta is exposed over a 40 km2 area of high relief (100–839 m) in the P–M fault block between the recently active Helike normal fault and the Pirgaki–Mamoussia (P–M) normal fault to the south (Figs. 1–3). The basement to this syn-rift succession comprises Triassic–Jurassic carbonates and Cretaceous flysch (emplaced as thrust sheets during the Hellenic orogeny at the end of the Mesozoic and Early Cainozoic). These pre-rift sequences crop out extensively to the south of the P–M fault and within the P–M fault block itself, further west in the Selinous River valley.

Between the P–M and Doumena Faults (Figs. 1–3), in what we term here the Doumena fault block, a thick and complex succession of mixed, relatively fine-grained alluvial red-beds (sandstones, pebble conglomerates, siltstones) and thick pebble–cobble grade conglomerate sequences crop out. These unconformably overlie the Hellenic basement. These rocks contrast strongly with the deltaic facies associations of the P–M fault block, and have not been observed in stratigraphic contact with them. Biostratigraphic data are scarce for this succession, although a time constraint is given by a lignite facies collected from boreholes in the vicinity of Kalavrita (south of the Doumena Fault) and dated as Lower Pliocene [14]. These coal facies currently represent the oldest dated level within what is here regarded as the syn-rift sequence. The age and stratigraphical relationships between this ‘alluvial’ succession and the Vouraikos fan delta are currently unknown, but are being investigated as part of this project.

In the 4–5 km wide P–M fault block (oriented WNW–ESE), the three-dimensional delta architecture is relatively well preserved and well exposed. The entire Vouraikos fan delta is composed of at least three stacked bodies with foreset dips ranging from NE to NW. The coarse-grained pebble to small boulder gravel-dominant sequences represent true Gilbert-type deltas with steeply inclined profiles characterized by large-scale, high-angle delta front (foreset) slopes. The gravels that comprise the main facies of the Gilbert delta are derived from pre-rift sediments.

The exposed Vouraikos fan delta is a restricted fragment of the complete system, since the frontal Helike Fault truncates the distal part of the delta (Figs. 1 and 2). Laterally, the Vouraikos system is limited by apparent pro-delta sandstones and siltstones in the west, where the northeastern margin of the Kerinitis fan delta may have encroached. To the east, a thick and extensive succession of well bedded fluvial conglomerates (gravel channel-belt), sandstones and thick mudstones (overbank) underlie the main body of the Vouraikos delta in the Ladopotamos River valley (Fig. 1). A very fine-grained shelly limestone bed (5 m thick) occurs at the top of this succession (location C, Fig. 1). An immediately overlying gravelly shallow marine sequence is abruptly followed by fine-grained clastic sediments probably of pro-delta facies.

The trace of the Helike Fault lies at the base of the topographic range front (Fig. 1). This east–west-trending range front is incised by a series of marine terraces, recording the history of uplift of the footwall block (De Martini et al., this issue). A Late Pleistocene age is given by De Martini et al. (this issue) for marine terraces in the footwalls of the Helike and Aegion Faults. The largest of the Vouraikos terraces, a depositional terrace, occurs at Trapeza and extends southward along the Ladopotamos River valley (Fig. 1). These range-front terraces are here interpreted to be younger than the red soil terraces that cap the Vouraikos fan delta (Figs. 1–3). These red capping soils have not yet been studied in detail, but are tentatively presumed to represent strong subaerial weathering of the abandoned delta substrate. They are conformable with the upper delta topsets and, as illustrated in Fig. 2, are tilted southward along with the rest of the Vouraikos sequence in the hangingwalls of the second-order Derveni and Asomati Faults (discussed below).

3 Biostratigraphical analyses and palaeoenvironmental data

In the Gulf of Corinth, a major problem in the interpretation of these Gilbert-type fan deltas is the lack of biostratigraphical information on the age of the various successions. In the literature, the age range given for these syn-rift facies is from Miocene to Holocene [1,3,12,13,15]. In this study, we chose to use palynology to address this problem, because of the lack of proven marine levels, and the likelihood of preservation of palynomorphs in the known facies. Samples were collected from sections at the western margin of the Vouraikos system, from relatively fine-grained bottomset facies at the base of the main fan delta conglomerate pile, and from fine-grained facies within the pile (locations in Figs. 1 and 2).

All studied samples show a great abundance of Cedrus and a low representation of Taxiodaceae. Liquidambar, Zelkova, Cathaya, Carya, Tsuga, Tricolporopollenites sibiricum are present. In terms of palaeoenvironment, there is a great abundance of Gymnosperm pollen. This is consistent with the dominant fluvial input. Very scarce and poorly preserved, probably marine, dinoflagellates were also found. From one sample to another, there is a great variability in oxidized phytoclasts, consistent with the hydrodynamic fluctuations in the sedimentary environment. All palynological associations collected indicate an Early Pleistocene age for the studied succession (J.-P. Suc, pers. comm., 2003).

4 Sedimentary facies associations: Description and interpretation

Within the Vouraikos fan delta, five sedimentary facies associations have been recognised, which are of the same general character as those described by Dart et al. [3] from the Kerinitis fan delta. Only brief descriptions are, therefore, given below.

(1) The topset facies association is predominantly composed of massive-crudely cross-stratified or horizontally-stratified cobble conglomerates. This facies is locally interbedded with thin reddened sandstones. Cyclical sequences, metres to tens of metres thick, are developed from prominent basal erosional surfaces, followed by massive, crudely bedded conglomerates and capped by thinner-bedded conglomerates, with development of reddened sandstones. Large-scale cross-stratified conglomerates occur in rare solitary sets. The texture and geometry of these conglomerates and sandstones are consistent with low-sinuosity gravel rivers that migrated on the sub-aerial fan delta top. One-metre- to tens-of-metres-scale sequences of interbedded pebble–cobble conglomerates, pebbly sandstones, red sandstones and reddened siltstones, the latter with very weak carbonate palaeosols, occur interstratified with the gravel-dominated topset sequences, and may represent sub-aerial, non-channelized environments on the delta top.

(2) The shoreline facies association shows, in contrast to the previous one, very well bedded and sorted, clast-supported pebble conglomerates with complex (landward- and seaward-dipping) low-angle large- scale stratification, as well as horizontally stratified beds. Finer facies of this association are represented by (1) burrowed, parallel-laminated sandstones and pebbly sandstones that are interpreted as beach and shoreface environments, and (2) monospecific shelly pebbly silts-sands, interpreted as back-barrier/lagoonal fines with storm washover sands and gravels. There are also rare thin bioclastic grain- and rudstone limestones that represent high-energy, shallow-water open marine carbonates (at locality B, Fig. 1). These occur in spatial association with the coastal facies conglomerates, described briefly above. Marine levels with corals, such as those described in the vicinity of Xylokastro [2], were not observed.

(3) The Gilbert foreset facies association shows well-bedded sequences of metre-scale pebble–cobble grade conglomerates, sand matrix-rich conglomerates with interbedded coarse and pebbly sandstones. Foresets are grossly planar (dipping at 20–30°) and show tangential basal terminations (Fig. 2). This facies association represents bedload and mass-flow emplacement of gravel and sand into a standing water body. The maximum set thickness of the association indicates palaeowater depths of 300–400 m.

(4) The bottomset facies association is characterized by thinly interbedded plane-laminated and rippled sandstones and conglomerates. Erosion surfaces and/or scours are common. In some places, soft sediment deformation occurs with small-scale slump folds and/or dewatering structures. They represent the base of Gilbert foresets, where low-angle slopes dip at values less than 10°.

(5) The prodelta facies association is represented by beige-coloured, massive to parallel-laminated sandstones and silty sandstones, thin pebble conglomerates and laminated siltstones. Floating gravel clasts commonly occur in the fine (sand and silt) facies. These deposits can be interpreted as the products of processes ranging from suspension fallout deposits to turbidity current deposits that are largely beyond influence of gravel input. They represent the deepest facies of all the associations observed in the Vouraikos fan delta system. This facies association is genetically related to the fan-delta foreset-bottomset structure of the system, and results from emplacement of major increments of clastic sediment following periodic fluvial flood events.

5 External envelope of the Vouraikos fan delta

A minimum of 800 m of conglomeratic facies are preserved in the centre of the Vouraikos fan delta. Internal delta architecture is complex with distinct packets of foresets, alluvial topsets and coastal gravel strata. Foreset dips vary from 10 to 30 degrees and dip directions swing from northeast on the eastern side to northwest to west-northwest on the western side. However, depositional dips are complicated by structural tilting related to normal faulting and/or regional uplift. Gentle southward tilting of the youngest (red soil terrace) sediments of the Asomati plateau is linked to late displacements on the Derveni and Asomati Faults (3–10 degrees; Fig. 2), which have displaced the topographic surface itself. Fig. 2 shows the basal contact of the conglomerate envelope on the eastern side of the Kerinitis River valley, dipping northward as the conglomerate package thickens rapidly. The northward thickening is exaggerated by displacements on secondary normal faults. It can be shown that conglomeratic foresets pass downward into finer bottomset and (inferentially) prodelta facies associations (e.g., at localities S3 and Y, Figs. 1 and 2), indicating that this basal conglomerate boundary is diachronous, with time lines passing downward along foresets into bottomsets. Thus, ages obtained in bottomset facies, such as at locality S3, represent ages for the laterally equivalent foresets.

At Mamoussia, on the western limit of the Vouraikos delta, the basal contact of the Vouraikos conglomerates lies at an altitude of 600 m (Fig. 2). Three kilometres to the east in the Vouraikos gorge, this contact lies below 200 m. Four kilometres further east, the contact is again found at 600 m. No transverse faults have been detected, which could explain these lateral changes in elevation of the basal conglomerate contact. Nor can normal faults within the Vouraikos delta (Fig. 1) accommodate this feature. This suggests a transversely concave shape to the base of the delta. The present-day Vouraikos River thus runs approximately along the axis of the Early-Pleistocene delta, where the deposits are thickest. These observations have important implications for the way in which deltas initiate and develop.

Ori et al. [13] propose that the Kerinitis and Vouraikos conglomerates represent the same delta body. However, the base of the Kerinitis fan delta lies below 200 m and its top at 800 m, while directly east the base of the Vouraikos delta is at 600 m and its top at 800 m. The front of the Kerinitis fan delta lies at least 3 km south from that of the Vouraikos, which is truncated by the Helike Fault. Thus, the Kerinitis and Vouraikos conglomerates represent independent delta bodies. Their relative age is currently unknown.

6 Extensional faulting

The accommodation space necessary for Gilbert delta deposition can be created by normal fault displacement combined with eustatic control, as demonstrated by numerical modelling [8]. In the Aigion region, the principal normal faults are spaced at 4 to 5 km (Aigion, Helike, Pirgaki–Mamoussia, Doumena Faults, Fig. 1). Numerous studies have discussed the geometries and kinematics of these faults [5,8]. Their vertical displacements are estimated to be in the order of 500–1000 m [7]. Accommodation space for the Vouraikos and Kerinitis delta systems was created by the P–M Fault with an estimated vertical offset of 800–1000 m [11]. Two sets of second-order normal faults cut the Vouraikos conglomerates. The first set parallels the major fault and is synsedimentary. These faults will be described in a later paper. The second set of steeply dipping normal faults, are spaced 1–2 km and have throws of 200–100 m (Fig. 2). These faults displace and tilt the topographic surface, indicating that they postdate delta development and are probably of the same age as the Helike Fault. Smaller faults, with displacements of tens of metres or less, are detected only sporadically, probably due to the lack of contrast in lithologies.

The orientation of the upper and lower envelopes of the Vouraikos and Kerinitis conglomeratic bodies (Fig. 2) does not support a southward tilt of the whole P–M fault block, as proposed by various authors [7, 8], but rather a horizontal or even a gentle northward dip of the whole block (independent of foreset dips). Local tilting of second-order faults is, however, observed within the delta itself. Firstly, gentle southward dips occur in the hangingwalls of post-depositional secondary faults (Derveni and Asomati Faults, Fig. 2), as discussed above. Secondly, a 2 km-wide packet of south-dipping (up to 40 degrees) topsets overlying horizontal foresets is observed in the Vouraikos gorge. These strata are tilted on one of several intra-delta syn-sedimentary faults.

The Vouraikos delta body terminates abruptly to the north against the Helike Fault (vertical displacement of 700–800 m [7]), forming a prominent range front with recent terraces and perched coastal deposits (e.g., at Trapeza, Figs. 1 and 3). These indicate that the Vouraikos delta body was progressively uplifted during episodic Quaternary displacement on the Helike Fault [4,10]. It is not yet clear whether this uplift can be attributed simply to footwall uplift or this was combined with a more regional process. The missing frontal part of the Vouraikos delta body must lie in the hangingwall of the Helike Fault, below the present Diakopfto fan delta, as represented schematically in Fig. 3.

7 Conclusions

This paper presents preliminary results of an ongoing detailed biostratigraphical, sedimentological and structural study of the Vouraikos fan delta. A number of salient points emerge that have regional implications.

(1) Preliminary palynological samples taken in and below the Vouraikos fan delta sequence indicate that it was deposited during the Early Pleistocene. This age span indicates rapid deposition rates, and also rapid surface uplift of the P–M block.

(2) The discovery of thin open marine limestones interbedded within the conglomeratic pile of the Vouraikos fan delta, spatially linked with coastal facies association conglomerates and sandstones, indicates that these Pleistocene systems were constructed in a marine water body.

(3) The large-scale foreset dip orientation, smaller-scale palaeocurrents and facies patterns demonstrate that sediment dispersal was from south to north, with delta progradation towards northeast and northwest, on average orthogonal to the bounding extensional faults of the area.

(4) The delta body has a concave base in transverse section, rising toward the east and west by at least 400 m. At its western limit, the diachronous base of the delta conglomerates dips gently northward in cross section and the conglomerate succession thickens northward.

(5) Accommodation space for the Vouraikos fan was created by up to 1000 m vertical displacement on the north dipping P–M fault. The P–M fault block does not tilt southward. However, smaller scale southward tilting occurs above second-order normal faults. Two generations of second-order faults can be distinguished (syn-sedimentary and post-depositional).

Acknowledgements

We thank Isabelle Moretti (IFP) for fruitful discussions both in the field and the lab. The authors are grateful to Bernard Courtinat and Jean-Pierre Suc (University of Lyon, France) for carrying out the palynological analyses. This work is supported by the ‘GdR Corinthe’ programme of the French Ministry of Education and Research.