Version française abrégée

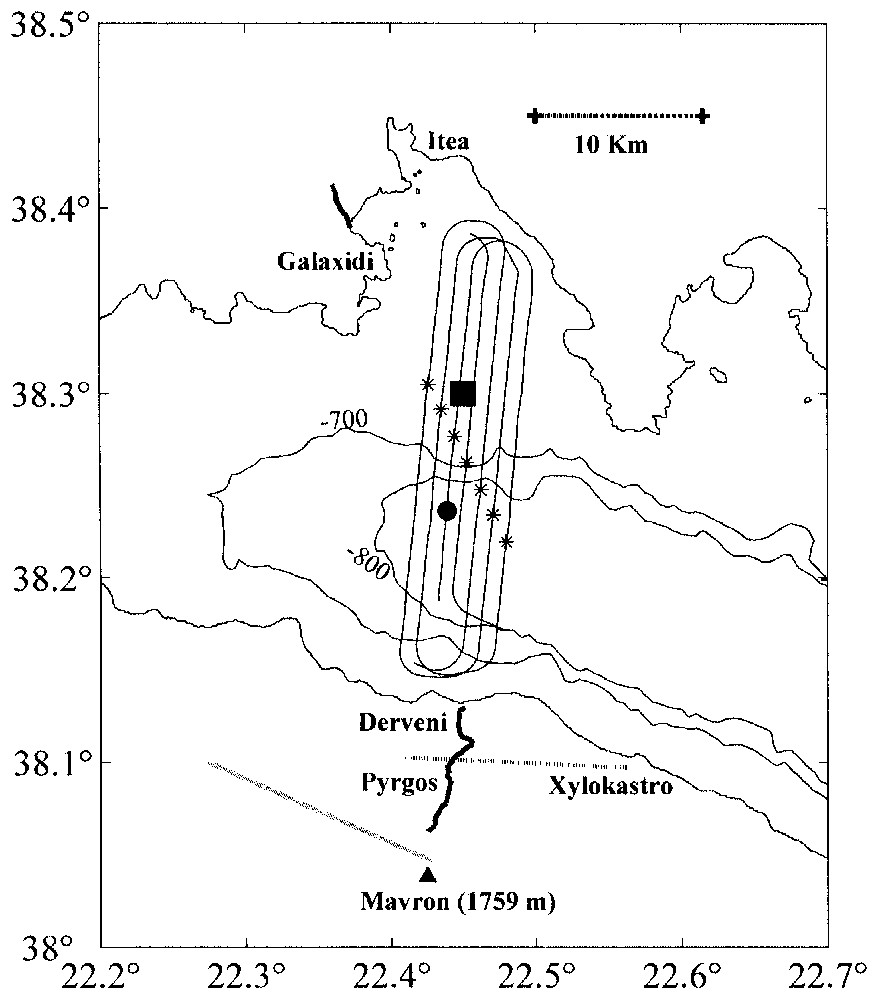

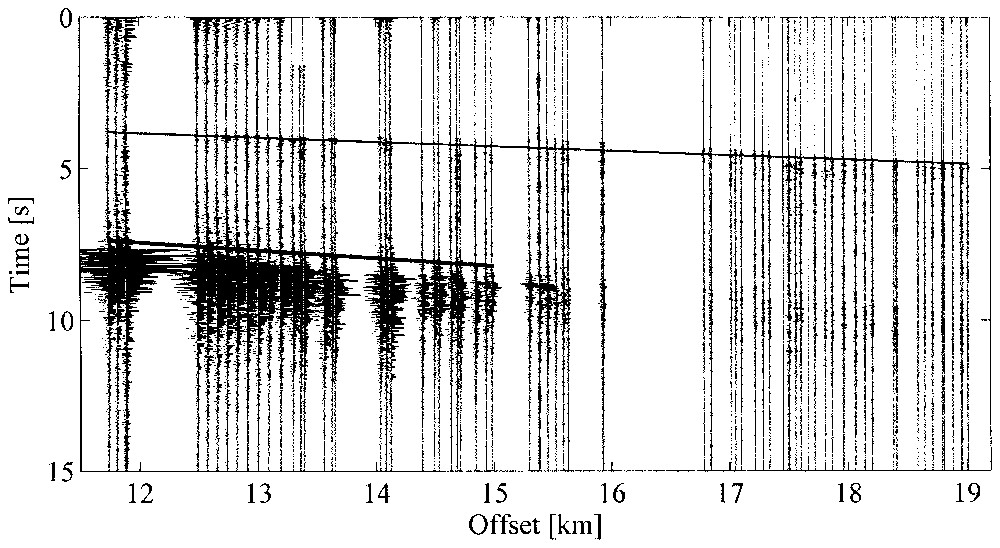

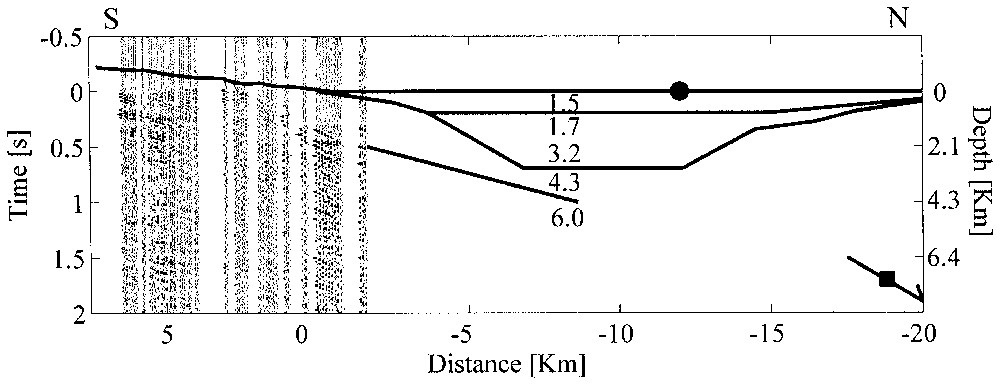

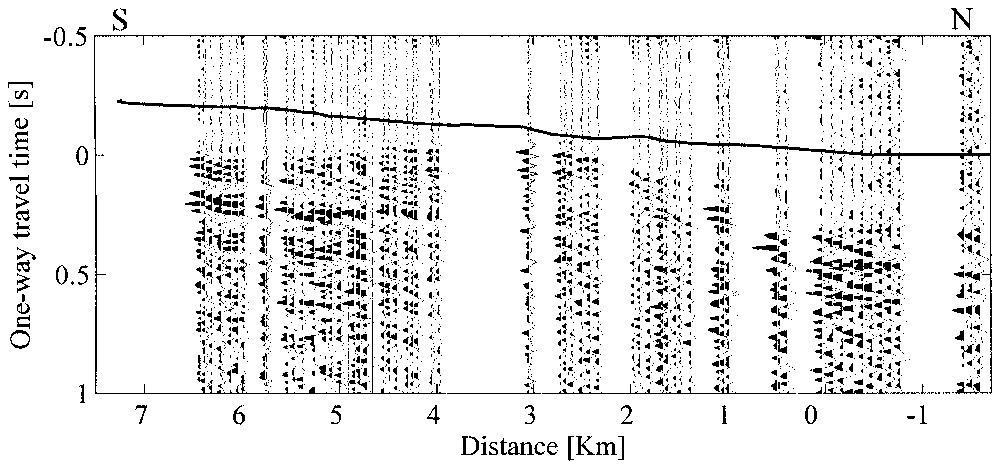

Nous présentons les observations faites avec deux dispositifs d'enregistrement sismiques placés sur les épaulements du rift de Corinthe [2,3] pendant la campagne de sismique réflexion du N/O Maurice Ewing en juillet 2001 [14] (Fig. 1). Sorel [13] a proposé un modèle d'évolution de la partie centrale du rift de Corinthe, dans lequel des blocs faillés se sont formés successivement du sud vers le nord, au-dessus d'une faille de détachement dans le socle. Cette zone pourrait être un des rares exemples de faille normale active à faible pendage dans la croûte supérieure [5,16]. Le réseau de Derveni (90 traces à intervalle de 80 m), orthogonal au rift, croise la faille de Xylokastro et va jusqu'au pied du mont Mavron. Le réseau de Galaxidi (30 traces) est localisé sur les carbonates des nappes externes des Hellénides [8], qui constituent les blocs faillés sous celui de Derveni. Seuls les tirs localisés dans la partie du golfe occupée par un bassin produisent des arrivées réfractées se propageant dans le socle sur le réseau de Derveni (Fig. 2). Une égalisation spectrale [7] permet de compenser l'atténuation des hautes fréquences et améliore la cohérence des enregistrements. Les arrivées réfractées sur le réseau de Derveni ont des vitesses apparentes supérieures à 8 km s−1, ce qui implique l'existence d'une interface pentée vers le nord. Leurs temps d'arrivée et leurs amplitudes sont lisses, ce qui montre qu'elles ne sont pas perturbées par les blocs faillés. Au contraire, les ondes dans l'eau converties au bord du bassin sont fortement atténuées au passage de la faille de Xylokastro. Elles indiquent que la vitesse moyenne dans les sédiments est 4,3 km s−1. Les ondes réfractées sur le réseau de Galaxidi indiquent une vitesse de 6 km s−1 dans le socle. On utilise les vitesses obtenues par migration profondeur avant sommation [6] dans le bassin. Les temps d'arrivée des ondes réfractées sur le réseau de Derveni sont ajustés avec une interface plane plongeant de 15° vers le nord entre deux milieux de vitesses 4,3 et 6 km s−1, sur une distance de 15 km. L'extrapolation vers le nord de cette interface (Fig. 4) passe par le séisme de Galaxidi de 1992, à 7,4 km de profondeur [3,10]. Une migration temps des arrivées réfractées vers le point d'émergence des rayons le long de l'interface fournit une image de l'interface sous le réseau (Fig. 3). Une sommation des images obtenues avec 10 tirs successifs améliore le rapport signal/bruit. L'image obtenue montre une ondulation en temps résultant des variations de vitesse dues aux variations d'épaisseur des sédiments synrift et à la topographie de l'interface. Le haut de l'ondulation correspond à des affleurements de carbonates dans le bloc au sud de la faille de Xylokastro. L'image migrée est conforme à la géométrie proposée par Sorel [13] pour le toit des écailles de socle sous les blocs faillés au-dessus du détachement.

Map of the central Corinth Rift showing the location of the Galaxidi and Derveni land seismic arrays and of the seismic profiles used in this study. The bathymetric contours outlining the basin in the gulf are in metres. The circle is the position of the shot shown in Fig. 2. The stars are the positions of shots used to determine basement velocity on the Galaxidi array. The Xylokastro and Valimi–Mount Mavron normal faults are indicated by stippled lines. The square indicates the epicenter of the 1992 Galaxidi low-angle normal faulting earthquake at 7.4 km depth.

Carte de la partie centrale du rift de Corinthe, montrant l'emplacement des réseaux sismiques terrestres de Galaxidi et de Derveni et des profils sismiques utilisés dans cette étude. Les contours bathymétriques entourant le bassin dans le golfe sont en mètres. Le rond indique la position du tir de la Fig. 2. Les étoiles indiquent les tirs utilisés pour déterminer la vitesse du socle sur le réseau de Galaxidi. Les failles normales de Xylokastro et de Valimi–mont Mavron sont indiquées par les lignes discontinues. Le carré représente l'épicentre du séisme de Galaxidi en 1992 à 7,4 km de profondeur, sur une faille normale de faible pendage.

Typical gather recorded on the Derveni array for a shot in the basin part of the gulf, with spectral balancing. The lines indicate travel times computed for the refracted first arrivals along a 15° north dipping plane interface between carbonates (4.3 km s−1) and basement (6 km s−1) and for the converted waves propagating in the hangingwall of the Xylokastro Fault (4.3 km s−1). The gap at offsets between 16 and 17 km corresponds to the Pyrgos village. The refracted waves propagating in the basement show smooth travel-time and amplitude variations. In contrast, the converted waves are strongly attenuated across the Xylokastro Fault.

Enregistrement typique sur le réseau de Derveni pour un tir localisé dans le bassin, après égalisation spectrale. Les traits montrent les temps de trajet calculés pour les premières arrivées, réfractées le long d'une interface plane pentée à 15° vers le nord, entre les carbonates (4,3 km s−1) et le socle (6 km s−1), et pour les ondes converties se propageant à 4,3 km s−1 dans le compartiment inférieur de la faille de Xylokastro. Le trou pour les déports entre 16 et 17 km correspond au village de Pyrgos. Les ondes réfractées montrent de faibles variations de temps de trajet et d'amplitude. Au contraire, les ondes converties sont fortement atténuées au passage de la faille de Xylokastro.

Cross-section of the Corinth Rift, showing the geometry of the shallow north-dipping interface determined with refracted waves in the Derveni area and under the basin. The circle is the position of the shot shown in Fig. 2. The square and the arrow indicate the location and the low-angle normal faulting focal mechanism of the 1992 Galaxidi earthquake. The numbers are the values of the velocities, in km s−1 used in water, in the basin sediments [6], in the Hellenides carbonates and in the basement.

Coupe à travers le rift de Corinthe, montrant la géométrie de l'interface peu profonde à pendage nord, déterminée avec les ondes réfractées dans la région de Derveni et sous le bassin. Le rond indique la position du tir de la Fig. 2. Le carré et la flèche représentent la position et le mécanisme au foyer sur une faille normale de faible pendage du séisme de Galaxidi en 1992. Les chiffres sont les valeurs des vitesses (en km s−1) utilisées dans l'eau, les sédiments du bassin [6], les carbonates des Hellénides et le socle.

Time-migrated section of the refraction interface beneath the Derveni array. The migration is done at a velocity of 4.3 km s−1 along the refracted rays emerging with a 45° critical angle from a 15° north-dipping interface. The line indicates topography converted to time at 4.3 km s−1. Distance is measured relative to the coast, with negative values at sea. The undulation of the interface reflects the block structure across the Xylokastro Fault.

Migration temps de l'interface de réfraction sous le réseau de Derveni. La migration est faite avec une vitesse de 4,3 km s−1 le long des rayons réfractés émergeant avec un angle critique de 45° d'une interface ayant un pendage de 15° vers le nord. La ligne montre la topographie convertie en temps à 4,3 km s−1. La distance est mesurée par rapport à la côte, avec des valeurs négatives en mer. L'ondulation de l'interface traduit la structure en blocs à travers la faille de Xylokastro.

1 Introduction

Seismic imaging of active continental rifts is difficult because extensional deformations produce strong shallow heterogeneities. Marked topography, transition from land to sea and block faulting produce sharp velocity contrasts that disrupt the coherence of wavefronts and enhance multiple scattering. The determination of the geometrical relationships between high- and low-angle border faults requires careful processing [4,11], especially designed experiments [1] or additional recordings at intermediate offset ranges [9]. In this paper, we report on seismic observations made with fixed recording arrays placed on the shoulders of the Corinth Rift during the R/V Maurice Ewing July 2001 marine survey in the gulf (Fig. 1).

2 Structural setting

The rapidly extending Corinth Rift includes a subsiding basin in the gulf and the uplifted coastal ranges of northern Peloponnesus [2]. The elevation difference between the basement of the basin [6] and the southern 2.3 km-high mountain range is at least 5 km over a horizontal distance of 30 km. Sorel [13] has proposed an evolution scenario for the central rift where block faulting has progressed from south to north above a detachment fault within the basement. Large earthquakes presently occur beneath the northern part of the gulf, at depths close to 10 km. The focal mechanisms and surface deformations resulting from the recent earthquakes, such as the 1992 Galaxidi event, are compatible with low-angle normal faulting [3]. These earthquakes may occur on the down-dip extension of a northward-dipping detachment linking upper-crustal block-faulting to lower crustal ductile flow [5] and thinning [15]. The central Corinth Rift may thus be one of the few known examples of seismically active low-angle normal fault in the upper crust [16].

The rift cuts the NNW-trending external thrust belt of the Hellenides [8] at an angle of 40°. In the Galaxidi area, carbonate nappes dip gently toward the south. Tilted blocks of carbonate nappe fragments and synrift sediments are observed in the northern Peloponnesus river valleys above an inferred detachment fault in a basement schist unit [13]. In the Derveni area, the east–west-trending Valimi and Xylokastro normal faults juxtapose limestones in the footwall with up-to-a-kilometre-thick marls and conglomerates deposits in the hangingwall.

3 Acquisition and processing of seismic data

The R/V Maurice Ewing July 2001 seismic survey in the Corinth Rift was shot with a 140-l tuned airgun array and was recorded on a 240-channel 6 km-long streamer [14]. Additional land recording of these powerful shots, fired at 50 m intervals, was made by a regional network of 40 three-component stations [17]. Two linear arrays located close to the coast near Derveni and Galaxidi were also installed to probe the shallow structure of the shoulders of the rift. The Derveni array, emplaced along the road Ligia–Pyrgos–Mount Mavron, is oriented at right angle to the rift. It crosses the westward extension of the Xylokastro Fault and extends up to the foot of Mount Mavron in the hangingwall of the Valimi Fault. The Galaxidi array is located directly on the carbonates of the Helennide nappes that constitute the faulted blocks beneath the Derveni array.

The 7.2 km long Derveni array has thirty three-channel stations, each channel recording a group of six vertical geophones. The group interval is 80 m, a value chosen to provide common shot gathers without excessive spatial aliasing. The southernmost trace, at the foot of Mount Mavron, is at an altitude of 979 m. The recording was continuous during the eight-day survey, using GPS timing. Access problems due to topography or housing in the Pyrgos village and temporary station failures caused irregularities and gaps in the spatial coverage. Ten stations were emplaced with the same parameters north of Galaxidi, on the northern coast.

The source array included airguns of different volumes and bubble periods. Destructive interferences occur between individual bubble oscillations and result in an impulsive signal at short range. The attenuation of high frequencies during propagation leads to a dominance of the lowest bubble frequency (6.5 Hz) at long range. Spectra of individual traces show broad peaks of decreasing amplitude at quasi-harmonic frequencies (multiples of 6.5 Hz). Spectral balancing using a simple method of spectrum equalization [7] improves the impulsiveness and the coherence of the records, making the detection of first and later arrivals easier.

4 Data analysis and velocity determination

There is a clear change in the trace gathers on the Derveni array with the position of the shots. For shots within the deep basin part of the gulf (Fig. 2), first arrivals correspond to refracted waves that have penetrated through the basin sediments into basement. High-amplitude later arrivals correspond to water waves converted at the steep southern flank of the gulf. For shots located on the shallow northern shelf, the refracted waves are not seen and the first arrivals are the converted water waves. Streamer data in the Itea Bay also show that transmission from water into the high-velocity carbonates of the Hellenide nappes is ineffective [12]. The maximum inline offset on the Derveni array for the waves refracted in the basement is therefore limited to 25 km.

The first arrivals on shot gathers at the Derveni array are characterized by an average apparent velocity larger than 8 km s−1. This implies the presence of a north-dipping interface at depth that reduces the angle between the conical wavefront and the surface. The decrease in the stations elevation from south to north decreases the apparent velocity. The observed variations of first arrival travel times and amplitudes across the array are quite smooth. This indicates that shallow block faulting does not perturb the propagation of the refracted waves.

In the absence of shots within the array, shallow velocities directly beneath the stations cannot be determined. However, the strong water waves efficiently converted at the gulf flank can be considered as direct waves probing the sedimentary layer. They are clearly observed at all offsets across the first half of the array. Shots located close to the coast show these waves most clearly at offsets between 2 and 6 km, with a velocity of 4.3 km s−1. In contrast with the refracted waves, these converted waves are strongly attenuated south of Pyrgos, in the footwall of the Xylokastro Fault.

The refracted first arrivals on the Galaxidi array have an apparent velocity close to 6 km s−1 for offsets between 13 and 25 km. Because the array is short (2.2 km), it is difficult to have a precise determination of this velocity. The array is emplaced directly on the carbonates of the Hellenide nappes in a direction subparallel to their strike. One may thus assume that dip effects on the refraction velocity are small. We therefore consider that a basement beneath the nappes has a velocity of 6 km s−1. Since the Derveni and Galaxidi arrays are installed on the same Hellenide unit, we assume that basement velocity is the same beneath both arrays. This implies a critical angle of 45° at the interface between the 4.3 km s−1 layer and the 6 km s−1 basement beneath the Derveni array.

5 Travel-time fit and migration of the refracted waves

We fit the first arrival times at the Derveni array for the shots that are located in the deepest part of the basin (a 5 km interval with water depths larger than 800 m). We assume that a continuous northward dipping plane interface separates carbonate units (4.3 km s−1) from basement (6 km s−1) beneath the array and the basin. We use velocities determined by prestack migration velocity analysis for the sediments in the basin [6]. We adjust the depth and the dip angle of the interface to fit a linear trend to the arrival times across the array. We find a uniform 15° northward dip along a 15 km distance and a 5.3 km depth of the interface beneath the shot indicated in Fig. 1. Half of the 15 km distance travelled by the refracted wave along the interface is under the basin.

Lateral velocity variations above the interface and depth variations of the interface beneath the array produce smooth time shifts relative to the times predicted for a plane interface. In addition, lateral velocity variations in basement outside the array would produce a shift in depth of the interface. Since it is not possible to discriminate between such velocity variations and depth variations of the interface with our data, we use time migration to obtain an image of the interface beneath the array. The migration is simply done along the refracted ray emerging from the plane interface because there is no evidence for diffraction, triplication or large slope variations in the refracted and following arrivals. Because the interface has an average dip of 15° toward the north and the critical angles is 45°, the refracted rays have an incidence angle of 30° with respect to the vertical. For a back-tilting angle of 30° for the blocks in the hangingwall of the shallow normal faults [13], the refracted rays cross the original block structure at near-normal incidence.

After migration (Fig. 3), the seismic traces are represented at the horizontal positions corresponding to the emergence of the refracted rays along the interface. The first-arrival times on the migrated section correspond to the one-way time to the interface along the vertical in a 4.3 km s−1 constant velocity medium. Topography converted to time with the same velocity is also shown. The migration shifts the traces seaward by almost 2 km. To improve the signal/noise ratio, we stacked migrated traces from 10 consecutive shots. Despite stacking, the records at the stations located close to the coast remain noisier than those at the stations located further inland. Because there is also a spatial gap in the traces, first arrivals at the northernmost stations remain somewhat ambiguous.

The migrated image beneath the Derveni array shows an undulation of the interface that reflects the block structure across the Xylokastro Fault. The top of the undulation occurs at the position (3 km distance from coast) of outcrops of calcareous units observed east of the profile in the footwall of the Xylokastro Fault [2]. Thickness variations in a wedge of synrift sediments in its hangingwall and the throw on the fault combine to cause a smooth seaward delay time increase of 0.5 s in a distance of 4 km. This delay corresponds to a 2.2 km depth increase at 4.3 km s−1 and to a local slope of the interface of 30°. Toward Mount Mavron, the almost constant delay time may indicate rollover anticline geometry. The image is consistent with the geometry proposed by Sorel [13] for the top surface of slivers of basement above a shallow detachment fault.

6 Conclusion

The installation of two land seismic spreads on the shoulders of the Corinth Rift during the July 2001 R/V Maurice Ewing seismic reflection campaign in the gulf has allowed to record clear refracted waves. The character of the waves indicates a smooth interface beneath the Derveni array. The arrival times can be fit with a 15° seaward dipping plane interface between a 4.3 km s−1 carbonate layer and a 6 km s−1 basement. This interface extends beneath the basin in the gulf. Its northward extrapolation goes through the hypocenter of the 1992 Galaxidi earthquake, a low-angle normal faulting event at 7.4 km depth (Fig. 4). The distribution of seismicity determined by local networks also shows a 15° dip in the seismically active zone [10]. Time migration of the refracted waves provides an image of the interface beneath the Derveni array. It shows an undulation that reflects the block structure across the Xylokastro Fault. Our data are consistent with the north-dipping detachment geometry proposed by Sorel [13].

Acknowledgements

NSF-ODP funded the EWING cruise. The ‘GDR Corinthe’ funded the installation of the land arrays. The geophone groups were lent by the University of Patras. J.M. Pi Alperin was supported by a J.A. Estenssoro fellowship from Fundacion YPF.