Version française abrégée

1 Introduction

L'altération latéritique des formations ultrabasiques de la Nouvelle-Calédonie a engendré au cours des 30 derniers millions d'années une accumulation de nickel au sein des manteaux d'altération. La Nouvelle-Calédonie est ainsi l'un des plus gros producteurs de nickel au monde. Depuis 1950 et la mise en place de nouvelles techniques mécaniques d'extraction du minerai, l'impact sur l'environnement a potentiellement augmenté parallèlement à la production.

De nombreuses études ont été réalisées sur les roches ultrabasiques à travers le monde quant à la genèse et à la géologie des différents gisements et sur le fonctionnement géochimique de l'altération de ces systèmes [5,6,10,17,19,20,24]. En revanche, très peu d'études se sont intéressées aux perturbations anthropiques de la végétation et, par ailleurs, aux interfaces sol/plante. Bien que la toxicité des sols ultrabasiques néo-calédoniens ait été démontrée pour des plantes cultivées non endémiques [1,2,12], des études sur les relations entre les caractéristiques physico-chimiques des sols et les plantes endémiques sont rares.

La Nouvelle-Calédonie fait partie des « points chauds » de biodiversité décrits par Myers et al. [16], c'est-à-dire des lieux présentant une forte concentration d'espèces endémiques avec de fortes pertes d'habitat. La flore actuelle représente seulement 28 % de la flore primaire. Cette flore calédonienne est formée de plus de 3300 espèces, dont 75 % sont endémiques au territoire [7]. Il existe une quarantaine d'espèces hyper-accumulatrices de nickel dans la flore calédonienne, recensées en grande majorité par Jaffré [6]. Le terme hyper-accumulatrice, utilisé pour la première fois par Brooks et al. [4], désigne des plantes qui présentent des teneurs en nickel supérieures à de matière sèche (0,1 %) dans leurs feuilles. Ces plantes intègrent le nickel dans leur métabolisme en utilisant divers complexes organométalliques [11,21], mais ni la distribution, ni la spéciation, ni le rôle intrinsèque du nickel n'est réellement connu.

L'objectif de notre étude est de préciser la distribution du nickel au sein d'une plante hyper-accumulatrice d'un sol nickélifère de Nouvelle-Calédonie et de mieux définir le cycle biogéochimique du nickel, en particulier les transferts du sol vers la plante. Nous exposons ici nos premiers résultats.

2 Site d'étude et méthodes analytiques

Le site d'étude est situé dans le Parc territorial de la rivière Bleue, au nord–est de Nouméa (Fig. 1), le socle sous-jacent est de nature harzburgitique et la végétation est une forêt primaire [7,24]. Le sol, peu induré, de couleur brune, contient des débris organiques divers et présente une texture rappelant celle d'une saprolite fine. Nous avons choisi d'étudier Sebertia acuminata, une Sapotacée, car cette plante possède une grande capacité de fixation du nickel : les teneurs atteignent () de matière sèche [7]. Les feuilles de Sebertia acuminata ont été échantillonnées, ainsi que le sol de la rhizosphère associé (0–20 cm de profondeur).

Map of the ultramafic bodies in New Caledonia (in grey) and study site location.

Carte de situation des massifs ultrabasiques (en gris) de Nouvelle-Calédonie et localisation du site d'étude.

Pour étudier la spéciation du nickel dans le sol, quatre techniques ont été employées. Une séparation granulométrique par dispersion à l'eau, puis sédimentation, a permis d'obtenir une fraction fine (<2 μm) et une fraction grossière. La caractérisation minéralogique du sol brut et des fractions granulométriques a été réalisée par diffraction de rayons X – diffractomètre Philips MPD 3710 du Centre européen de recherche et d'enseignement de géosciences de l'environnement (Cerege) – et par microscopie électronique à balayage (MEB) (GEOL 6320 F à pointe à émission de champs), couplé à un spectromètre à énergie dispersive (EDS) (Tracor Norther, Centre de recherche sur les mécanismes de croissance cristalline, CRMC2) après métallisation au carbone. Onze éléments ont été dosés par spectrométrie d'émission atomique couplée à une torche à plasma (ICP–AES), après fusion au métaborate de lithium au Cerege : Al, Ca, Fe, K, Mg, Mn, Na, P, Si, Ti et Ni. Les analyses chimiques ont été répétées trois fois sur le même échantillon. La disponibilité du nickel a été définie par extraction chimique séquentielle par deux extractants KCl 1 M (NiKCl) et DTPA 0,005 M+CaCl2 0,01 M (NiDTPA), selon la méthode de Lindsay et Norvell [13] modifiée par Bourdon et al. [3].

Pour étudier le nickel dans la plante Sebertia acuminata, quatre techniques ont également été utilisées. L'analyse chimique totale du nickel dans les feuilles de Sebertia acuminata a été réalisée par ICP–AES au Cerege, après dissolution à l'acide nitrique. Les phytolithes ont été extraits par oxydation humide [9] et calcination. Leur observation ainsi que celle des caractéristiques foliaires de la plante ont été réalisées par MEB (Philips 715 équipé d'un Edax X′ du Centre pluridisciplinaire de microscopie électronique (CP2M)). L'EDS a été utilisée pour les cartographies élémentaires (Si, Ni, S) dans les feuilles. L'étude de l'environnement atomique du nickel par EXAFS (Extended X-Ray Absorption Fine Structure Spectroscopy) au seuil k du nickel a été réalisée en mode fluorescence sur la ligne X23A2, NSLS (BNL, Upton, NY, par Jérôme Rose) ; les références utilisées ont été les suivantes : Ni-acétylacétonate (Ni-acac), Ni-phtalocyanine, NiO, NiOH2, NiFe2O4 et NiS.

3 Résultats

3.1 Le nickel dans le sol

Les résultats de la séparation granulométrique donnent environ 1 % de fraction fine et 99 % de fraction grossière. Les spectres de diffraction de rayons X montrent une prédominance des oxy-hydroxydes de fer (gœthite et hématite), avec des quantités mineures en serpentine, willemséite (talc nickélifère) et quartz. La fraction grossière présente la même distribution minéralogique que le sol brut. La fraction fine est semblable, mais sans quartz. Les résultats de microscopie électronique (MEB) donnent les mêmes résultats, à savoir une prédominance des minéraux secondaires, avec quelques phases primaires minoritaires. Par ailleurs, les analyses ponctuelles EDS indiquent que le nickel est lié à la gœthite. Le Tableau 1 donne la composition chimique totale du sol. La concentration en Fe2O3 est la plus importante (41,02 %), tandis que SiO2 et Al2O3 ont des valeurs du même ordre de grandeur (9,96 et 7,23 %, respectivement), supérieures à MgO et NiO (3,21 et 1,55 %, respectivement). Les autres éléments peuvent être considérés comme des traces. Les concentrations en nickel échangeable (NiKCl, ) et extractible par DTPA (NiDTPA, ) (Tableau 1), ce qui correspond au nickel disponible, sont beaucoup plus faibles que les teneurs en nickel total, soit 1,6 et 3,7 % respectivement.

Chemical analysis of the soil, of the soil extracts and of the leaf of Sebertia acuminata

Analyses chimiques du sol, des extraits de sol et de la feuille de Sebertia acuminata

| Soil | ||

| Total | Weight [%] | Error [%] |

| Fe2O3 | 41.02 | 0.31 |

| SiO2 | 9.96 | 0.23 |

| Al2O3 | 7.23 | 0.24 |

| MgO | 3.21 | 0.29 |

| NiO | 1.55 | 0.94 |

| MnO | 0.87 | 0.31 |

| CaO | 0.35 | 0.29 |

| P2O5 | 0.19 | 1.01 |

| TiO2 | 0.17 | 0.69 |

| Na2O | 0.13 | 2.05 |

| K2O | 0.06 | 0.21 |

| Loss of ignition | 35.25 | |

| Total | 99.99 | |

| Extraction | Error [] | |

| NiKCl [] | 234 | 3 |

| NiDTPA [] | 560 | 7 |

| Plant | ||

| Ni [] | Error [] | |

| Sebertia acuminata | 25 762 | 808 |

3.2 Le nickel dans Sebertia acuminata

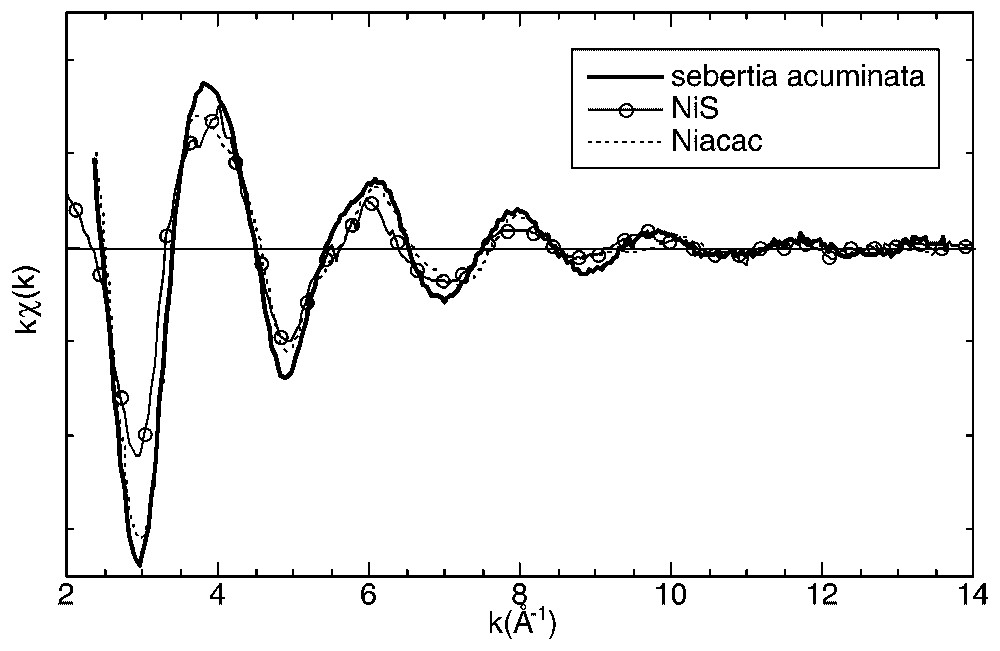

Le Tableau 1 donne les concentrations en nickel des feuilles de Sebertia acuminata. Cette concentration moyenne de est supérieure à celle donnée par Jaffré [7,8], mais du même ordre de grandeur. La Fig. 2 montre des compositions élémentaires des feuilles de Sebertia acuminata. Ces images indiquent que la silice est située autour des cellules foliaires, alors que le nickel et le soufre se trouvent à l'intérieur des cellules. Cette cartographie montre aussi des accumulations spécifiques de silice dans les cellules (Fig. 2b). L'observation et l'analyse chimique ponctuelle (MEB couplé à EDS) indiquent clairement que ces particules sont des phytolithes (Fig. 3). Le spectre EXAFS de Sebertia acuminata est comparé à des spectres de composés de référence (Fig. 4). Il apparaı̂t clairement que le spectre de Sebertia acuminata possède une amplitude et des oscillations très différentes de celles de NiFe2O4 et de Ni-phtalocyanine. Cela signifie que, s'il existe des structures nickélifères de ce type au sein des feuilles, elles restent très minoritaires et ne sont pas détectées par EXAFS. De même, les spectres de NiO et Ni(OH)2 sont assez différents de celui de Sebertia acuminata, notamment dans le domaine 4,5–6,0 Å. Seuls les spectres de NiS et Ni-acac sont assez comparables à celui de Sebertia acuminata. La Fig. 5 présente la superposition des spectres de NiS, Ni-acac avec celui de Sebertia acuminata. Elle indique que l'amplitude des oscillations du spectre de NiS est plus faible que celle du spectre de Sebertia acuminata. Il semble ainsi que le spectre le plus proche de celui de Sebertia acuminata soit celui de Ni-acac.

1-mm2 SEM image of the leaf of Sebertia acuminata (A) and EDS element mapping of Si (B), Ni (C), S (D), Si and Ni overlap (E), Si, Ni and S overlap (F).

Photographie MEB d'une surface de 1 mm2 de la feuille de Sebertia acuminata (A) et cartographie élémentaire par EDS de Si (B), Ni (C), S (D), superposition Si Ni (E), superposition Si, Ni, S (F).

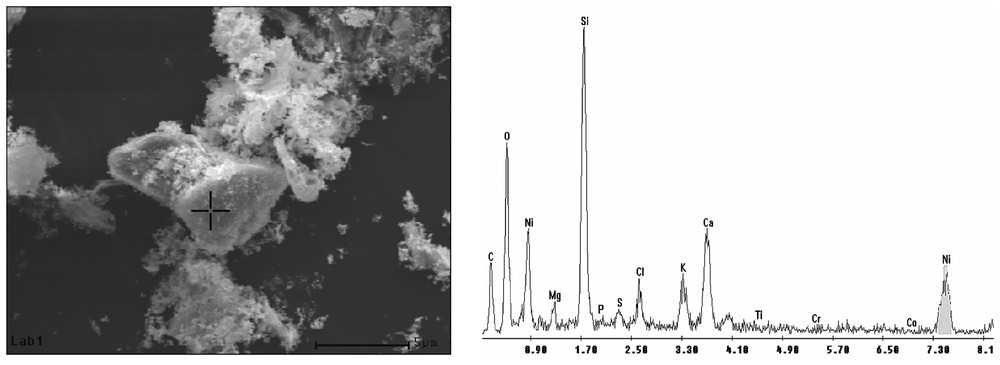

SEM image of a phytolithe with the EDS pointer for the location of the chemical analysis and associated spectrum.

Photographie MEB d'un phytolithe avec la localisation de l'analyse chimique par EDS et spectre associé.

EXAFS spectrum of Sebertia acuminata compared to spectra of reference materials.

Spectre EXAFS de Sebertia acuminata comparé à des spectres de composés de référence.

Superposition of EXAFS spectra of Ni-acac, NiS with the spectrum of Sebertia acuminata.

Superposition des spectres de Ni-acac, NiS avec celui de Sebertia acuminata.

4 Discussion

Le sol présent dans le Parc territorial de la rivière Bleue, formé principalement de minéraux supergènes (gœthite, hématite) est de type alluvial. Les concentrations chimiques des éléments sont semblables à celles trouvées dans les mêmes types de sols du Sud de la Grande Terre [10,24]. Par ailleurs, les résultats des analyses EDS indiquent que le nickel est majoritairement lié aux oxy-hydroxydes de fer. Les teneurs en nickel échangeable (NiKCl) et extractible par DTPA sont, en revanche, beaucoup plus faibles que les teneurs en nickel total, 1,6 et 3,7 %, respectivement. Le nickel lié aux oxy-hydroxydes de fer serait donc localisé dans les structures cristallines [23] et peu disponible pour les plantes. Le nickel assimilable par les plantes est donc probablement localisé dans la litière (complexes organométalliques).

Sebertia acuminata est un puissant extracteur et accumulateur de nickel. Après absorption, elle fixe de manière différentielle le nickel et la silice, l'un à l'intérieur des cellules, probablement dans les vacuoles, l'autre comme constituant des parois et sous forme de phytolithes dans les cellules.

Les résultats EXAFS montrent que le spectre de référence le plus proche de celui de Sebertia acuminata est celui de Ni-acétylacétonate, où le nickel est entouré de six atomes d'oxygène à environ 2 Å et de six atomes de carbone à environ 3,2 Å. Il apparaı̂t ainsi que le nickel pour Sebertia acuminata se trouve majoritairement dans un environnement atomique carboné assez proche de celui de Ni-acac. Il ne semble pas y avoir de précipitation d'oxyde ou d'hydroxyde de Ni. À l'échelle moléculaire, la structure de Ni-acac n'est pas très éloignée de celle du citrate de nickel, nos résultats corroborant ceux de Lee et al. [11] et Sagner et al. [22], qui mettent en évidence la présence de Ni-citrate dans le latex de cette plante. Le nickel dans les feuilles de Sebertia acuminata serait donc majoritairement sous forme de complexes organométalliques de type citrate.

5 Conclusion

Le nickel trouvé dans le sol du Parc territorial de la rivière Bleue est en majorité dans le réseau cristallin des gœthites. La fraction considérée comme disponible à la plante est relativement faible. Toutefois, elle est bien plus élevée que les teneurs moyennes des sols latéritiques. Cette fraction serait ainsi absorbée par les végétaux. Sebertia acuminata fixerait le nickel dans ses feuilles, où il serait localisé dans les vacuoles. En revanche, la silice se trouve dans les parois et sous forme de phytolithes. Sebertia acuminata répartirait et fixerait de manière différentielle Ni et Si. Ni serait préférentiellement sous forme organométallique, avec un environnement atomique et une structure moléculaire proche de celle du citrate de nickel. L'étude approfondie de ces plantes et des écosystèmes associés (relations sol/plantes/microorganismes) est incontournable dans les itinéraires de restauration écologique.

1 Introduction

In New Caledonia, as a result of the long-term lateritic weathering (30 Ma) of the ultramafic rocks, nickel has been concentrated in the thick regolith and in overlying soils. New Caledonia is thus one of the largest nickel producers in the world. Since 1865 and the discovery of the nickel ore by Jules Garnier, nickel has been extracted in open cast mines. At first, nickel was mined on a small scale, but since 1950 and the use of new mechanical extraction techniques, the production has increased considerably as well as the awareness of the environmental impacts of the nickel mines.

Numerous studies have been carried out on ultramafic rocks and their lateritic weathering mantles throughout the world, on the genesis and on the geology of the different ore bodies, and on the geochemistry of the weathering processes [5,6,10,17,19,20,24]. Very few studies have been devoted to the relation between the soil and the vegetation cover and more specifically to the plant–soil relationships. The toxicity of the New Caledonian ultramafic soils has been shown, however, in particular the impact of nickel on crops and on plants not adapted to these soils as well as the nickel availability in the soils [1,2,12], but there are no studies that look at the interactions between the soil's physical and chemical properties and endemic plants.

Furthermore, New Caledonia has been identified by Myers et al. [16] as a ‘biodiversity hotspot’, which means that very high concentrations of endemic plant species are undergoing exceptional loss of habitat, the extent of the current primary vegetation representing only 28% of the original one. The current flora is formed of more than 3300 species, of which 75% are endemic to the island [7]. Jaffré [7] has registered 40 of these endemic plants as nickel hyperaccumulators. The term ‘nickel hyperaccumulators’, first used by Brooks et al. [4], describes plants that can accumulate nickel at concentrations greater than dry weight (0.1%) in their leaves. These plants integrate this metal in their metabolism inhibiting its effect using various organic complexes, nickel (II) citrate complex with Ni(H2O)62+ as the major ionic component in various New Caledonian hyperaccumulators [11,22], but little is known about the distribution, the speciation or the intrinsic role of nickel. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that the vegetation cover plays a major role in the chemical cycling of elements during global weathering processes [15].

The aim of this study is thus to document the distribution of nickel in the leaves of a nickel hyperaccumulator from New Caledonia and in the associated soil, in order to get a better understanding of the biogeochemical cycle of nickel from the soil to the plant. We report here our preliminary results.

2 Study site and field sampling

New Caledonia is a small island (500 km long and 50 km wide) located in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. Its tropical humid climate is governed by trade winds. The sampling was done in the southern part of the island in the ‘Parc territorial de la rivière Bleue’ (Fig. 1). This region receives 2000 to rainfall, the mean temperature is about 22 °C with a 7 °C daily and seasonal variation [14].

The underlying bedrock is formed of hartzburgite, which is part of the southern peridotitic body [24]. The long-term lateritic weathering has led to the formation of a thick weathering mantle made up essentially of iron oxi-hydroxides. The soil sampled in this study is a dark brown coloured forest soil of alluvial origin underlying a thin litter. Only the top 20 cm were sampled. The soil is weakly indurated, of fine texture and looks like an earthy saprolite. The soil samples were oven-dried at 60 °C and sieved at 2 mm.

The vegetation is a tropical forest, in which four nickel hyperaccumulators were identified: Hybanthus austro-caledonicus, Psychotria douarrei, Sebertia acuminata and Homalium kanaliense [7]. We have chosen to study Sebertia acuminata, a Sapotaceae, because among these hyperaccumulators it is the species that is likely to accumulate the largest amount of nickel: dry weight concentrations of of nickel were measured by Jaffré [7,8] in its leaves. The leaves of the plant were sampled and washed with distilled water; half the sample was kept fresh, half was oven-dried at 60 °C.

3 Analytical method

3.1 Soil analysis

In order to determine the nickel speciation in the soil, four different techniques were used. A rough granulometric separation was done by water dispersion and sedimentation in order to get a fine fraction (<2 μm) and a coarse fraction. The mineralogy of the bulk soil and of each size fraction was established by X-ray diffraction (diffractometer Philips MPD 3710 of the CEREGE) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) (GEOL 6320F field-emission microscope equipped with an EDS) (Tracor Norther at the CRMC2 in Luminy) after carbon coating. Eleven elements were measured by ICP–AES after alkaline fusion (lithium metaborate) at the CEREGE: Al, Ca, Fe, K Mg, Mn, Na, P, Si, Ti, and Ni. The chemical analyses were replicated three times on the same sample. Finally, to study the nickel availability, two chemical extractants were used sequentially, KCl (NiKCl) and DTPA 0.005 M+CaCl2 0.01 M (NiDTPA) according to the Lindsay and Norvell method [13] modified by Bourdon et al. [3]. 2.5 g of soil are shaken for 1 h with 25 ml of a 1 M KCl solution, centrifuged 15 min at 2000 rpm and filtered; the residue is shaken for 1 h with a 0.005 M DTPA+0.01 M CaCl2 solution adjusted at pH 5.3, centrifuged 15 min at 2000 rpm and filtered. Both solutions were analysed for Ni using an ICP–AES at the CEREGE. The first extractant enables the measurement of the exchangeable cations at the soil pH [21] and the second is a chelating agent used to assess the availability of various metals to plants [13].

3.2 Plant analysis

Similarly to the soil samples, the distribution of nickel in the leaves was established using various techniques. The chemical analysis of nickel in the leaves of Sebertia acuminata was performed using the ICP–AES at the CEREGE after nitric-acid microwave dissolution. Phytolithes were extracted from the leaves using the incineration technique after preparation by ‘wet oxidation’ [8]. The observation of the foliar structure and phytolithes was done using a SEM (Philips 715 equipped with an EDS Edax X′ at the CP2M) The EDS was used to set up elemental (Si, Ni, S) mapping of the leaves. Finally, the atomic environment of nickel was studied using the EXAFS technique: the plant samples were dried and crushed in order to get a homogenous powder, whereas Ni K edge EXAFS experiments were performed on the X23A2 beamline, NSLS (BNL, Upton, NY, USA). The reference materials used were, Ni acetylacetonate (Ni-acac), Ni phtalocyanine (Ni-phta), NiO, NiOH2 NiFe2O4, and NiS.

4 Results

4.1 Nickel in the soil

The results of the granulometric separation show that approximately 1% is in the fine fraction (below 2 μm) and 99% in the coarse fraction. The X-ray diffraction patterns show that the soil is mainly made of goethite and hematite, with minor quantities of serpentine, willemseite (Ni-rich talc) and quartz. The same mineralogical distribution is observed in the bulk soil, the fine and the coarse fractions, with a lack of quartz in the fine fraction. The SEM gives the same results as the XRD, that is a dominance of goethite with some residual primary minerals. The EDS results show that nickel is linked to goethite.

Table 1 gives the chemical composition of the soil. The concentration of Fe2O3 is the largest (41.02%), SiO2 and Al2O3 have comparable values (9.96 and 7.23%, respectively) larger than MgO and NiO (3.21 and 1.55%, respectively). The other elements can be considered as trace elements. Concentrations of exchangeable nickel (NiKCl) and extractable nickel by DTPA (NiDTPA), of respectively 234 and 560 , are very low compared to the total nickel concentration, 1.6 and 3.7%, respectively.

4.2 Nickel in Sebertia acuminata

The nickel concentration of the leaves of Sebertia acuminata are presented in Table 1. The average concentration of is higher than the one observed by Jaffré [7,8], but of the same order of magnitude.

Fig. 2(a) shows a SEM image of a 1 mm2 zone of the inferior part of a leaf of Sebertia acuminata. Figs. 2(b)–(d) represent respectively the Si, Ni and S maps of that area obtained by EDS. Figs. 2(e) and (f) are the overlaps of Ni/Si and Ni/Si/S element distributions. These images show that silica is distributed around the leaf cells, whereas nickel and sulphur are found in the cells. The micro-chemical mapping also shows specific accumulations of silica in the cells (Fig. 2(b)). A phytolithe extraction done on the leaves, followed by SEM observations (Fig. 3), shows the presence of phytolithe accumulation in the leaves of Sebertia acuminata. The EDS chemical analysis of the phytolithe (Fig. 3) indicates that it is mainly made of silica, confirming the results obtained by the mapping of the leaf.

The Sebertia acuminata EXAFS spectrum is compared to spectra of reference materials (Fig. 4). An EXAFS spectrum provides information on the atomic structure around the analysed atom. The amplitude and phase of the EXAFS oscillations are directly linked to the nature, distance and number of atoms present around the central atom. Thus the comparison of the Sebertia acuminata spectrum with those of the reference materials allows a better understanding of the atomic environment of Ni in the leaves. The amplitude and phase of the oscillations of the Sebertia acuminata spectrum are very different from those of NiFe2O4 and Ni-phtalocyanine. Similarly, the NiO and Ni(OH)2 spectra are different from the Sebertia acuminata spectrum, especially in the 4.5–6 Å area, only the NiS and Ni-acac spectra are comparable. Fig. 5 shows an overlap of the NiS, Ni-acac and Sebertia acuminata spectra. The magnitude of the oscillations of the NiS spectrum is weaker than those of the Sebertia acuminata spectrum. Thus, it seems that the Ni-acac spectrum is the most comparable to the spectrum of Sebertia acuminata.

5 Discussion

The soil of the Parc territorial de la rivière Bleue is mainly composed of a coarse granulometric fraction (2–2000 μm), the fine fraction (<2 μm) representing only 1% of the bulk soil. X-ray diffraction and EDS analysis reveal the presence of goethite as the major mineral constituent with hematite, also very abundant. Serpentine is present in very small quantities. The presence of secondary minerals in abundance indicates that the weathering gradient of the soil is high. This is emphasized by the absence of pyroxenes and olivine group minerals, which make up the underlying ultramafic bedrock that has been completely weathered.

The nickel concentration of the soil (1.55%) is close to results observed in similar soils of the southern ultramafic massif of New Caledonia [9,24]. The other results (Fe2O3, SiO2, Al2O3, and MgO concentrations) are in agreement with the mineralogy of the soil, iron being the most important element. The EDS analysis shows that nickel is present in relatively high concentration linked to the iron hydroxides (2–3%) and in very low concentrations associated to the serpentine minerals (less than 1%). These amounts are 27 times larger than the extractable by DTPA nickel concentration and 66 times larger than the exchangeable nickel concentration measured after a KCl extraction. The ignition loss, which provides a good estimation of the organic matter content, is relatively high. The nickel linked to the goethite of the soil is trapped in its crystalline structure [18,23] and is therefore not readily available to the plants.

Thus a major part of the nickel available to plants is probably linked to the organic matter as organometallic complexes located in the litter.

Sebertia acuminata has very high concentrations of nickel in its leaves (approximately ).

The element maps in the leaves of Sebertia acuminata show a differential distribution of nickel and silica. Sulphur is located in the same area as nickel. A comparison of the leaf SEM image with the maps suggests that nickel and sulphur are located in the cells, whereas silica forms the framework of the cells. The presence of silica phytolithes (Ct opal) confirms the separation of nickel and silica within the cells. The plant appears to translocate these elements differentially, nickel in the cell vacuoles and silica either for the cell framework or as phytolithes.

The EXAFS analysis shows that the amplitude and phase of the oscillations of the Sebertia acuminata spectrum are very different from those of NiFe2O4 and Ni-phtalocyanine. This means that if these structures exist in the leaves, they are not sufficiently developed to be detected by EXAFS. Furthermore the results show that the Ni-acetylacetonate (Ni-acac) spectrum is the most comparable to the spectrum of Sebertia acuminata. In Ni-acac, Ni is surrounded by six oxygen atoms located at approximately 2 Å and six carbon atoms at approximately 3.2 Å. Thus nickel in the leaves of Sebertia acuminata is mainly in a carbon atomic environment similar to Ni-acac and nickel oxides or hydroxides are not present. Furthermore, the atomic structure of Ni-acac at an EXAFS level is close to the structure of Ni-citrate already found in the latex of the plant by Lee et al. [11] and Sagner et al. [22], indicating that nickel in the leaves of Sebertia acuminata is probably present mainly as an organometallic complex.

6 Conclusions, perspectives

The soil of the ‘Parc territorial de la rivière Bleue’ is mainly formed of goethite and hematite, which contain significant amounts of nickel. However, most of this nickel is trapped in the network of goethite, and therefore not easily available to plants. The concentration of available nickel in the soil is relatively low compared to the total soil nickel content, but high compared to available nickel contents in other lateritic soils of the Tropical Belt. The nickel is probably located in the litter.

Sebertia acuminata is a nickel hyperaccumulator; it contains approximately 2.5% nickel in its leaves. The nickel located in the leaf cells is probably located in the vacuoles, whereas silica is part of the leaf framework and contributes to the formation of phytolithes. Nickel is present as organometallic complexes, probably with citrate as the main ligand.

This plant is able to absorb nickel at high content, inhibit its phytotoxic effect, translocate it towards its leaves and accumulate it in its cells. In order to define the pathways of ecological restoration of old mining sites, it is essential to study a larger number of hyperaccumulators in various environmental settings. The study of the speciation of nickel in the various mine soils with emphasis on the bioavailable fraction is essential, as is a greater understanding of the process of absorption and accumulation of nickel in these plants.

Acknowledgements

This paper is a contribution of the IRD UR 037 team, the authors are grateful to Olivier Grauby (CRMC2), Ahmed Charaı̈ (CP2M) and Jean-Claude Germanique for technical advice and lab work, Anicet Beauvais, Dominique Chardon, Anne Perrier, Alain Perrier and Cécile Bourgois for corrections.