Version française abrégée

1 Introduction

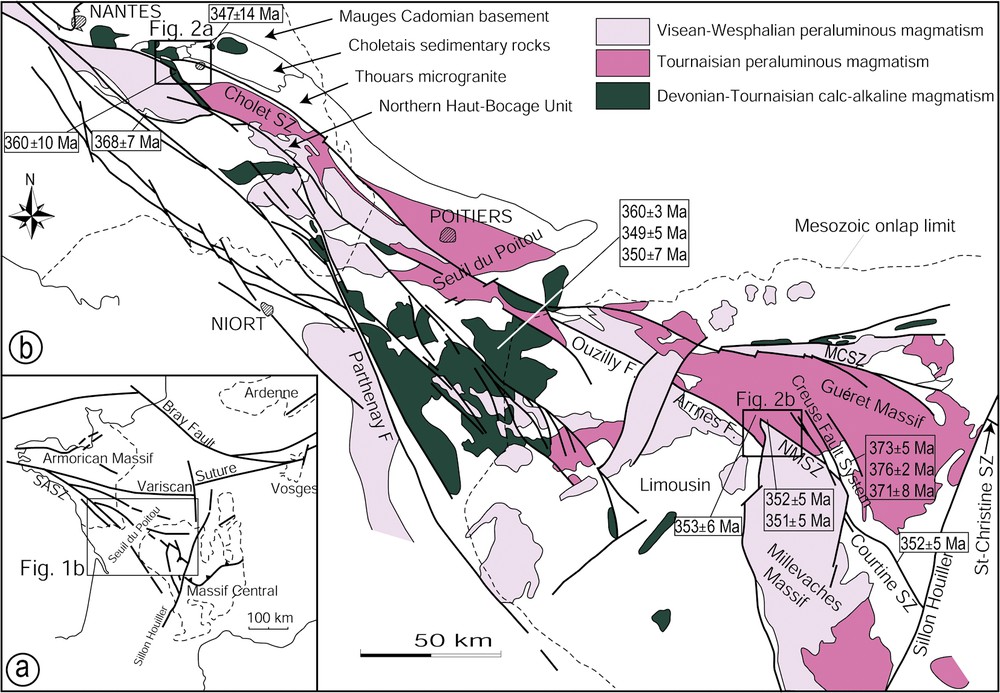

Deux zones de cisaillement ductile appartenant à la branche sud du cisaillement Sud-Armoricain [1,2,8,16] sont étudiées : le cisaillement de Cholet, au sud-est du Massif armoricain, et le cisaillement Nord-Millevaches–La Courtine, à l'ouest du Massif central. Les données structurales et géochronologiques acquises sur ces failles ductiles apportent de nouvelles contraintes sur l'âge du fonctionnement du cisaillement Sud-Armoricain et sur l'âge de la tectonique transcurrente dans la chaîne varisque ouest-européenne. Cette dernière s'est produite peu après l'anatexie frasnienne (378–368 Ma) et avant le magmatisme bimodal tournaisien (environ 355 Ma).

2 Contexte géologique régional

Le schéma structural du socle du Seuil du Poitou sous couverture [25] montre la continuité du cisaillement de Cholet avec les failles d'Ouzilly, d'Arrènes, et du cisaillement Nord-Millevaches–La Courtine (Fig. 1a, b). Le cisaillement de Cholet (Fig. 2a) sépare l'unité des Mauges de l'unité du Haut Bocage. L'unité des Mauges est composée d'un socle cadomien recouvert d'une série sédimentaire cambro-ordovicienne, dite du Choletais. Les dépôts cambriens sont intrudés par le microgranite cambrien de Thouars [30]. L'unité du Haut Bocage vendéen est formée des migmatites de la Tessouale.

(a) Structural sketch map of the Armorican and Massif Central Variscan strike-slip faults. (b) Synthetic structural map of the southeastern Armorican Massif and northwestern Massif Central, with emphasis on the various Hercynian granitic series.

(a) Carte structurale schématique des décrochements varisques du Massif central et du Massif armoricain. (b) Carte structurale synthétique du Sud-Est du Massif armoricain et du Nord-Ouest du Massif central, montrant les différentes associations magmatiques hercyniennes.

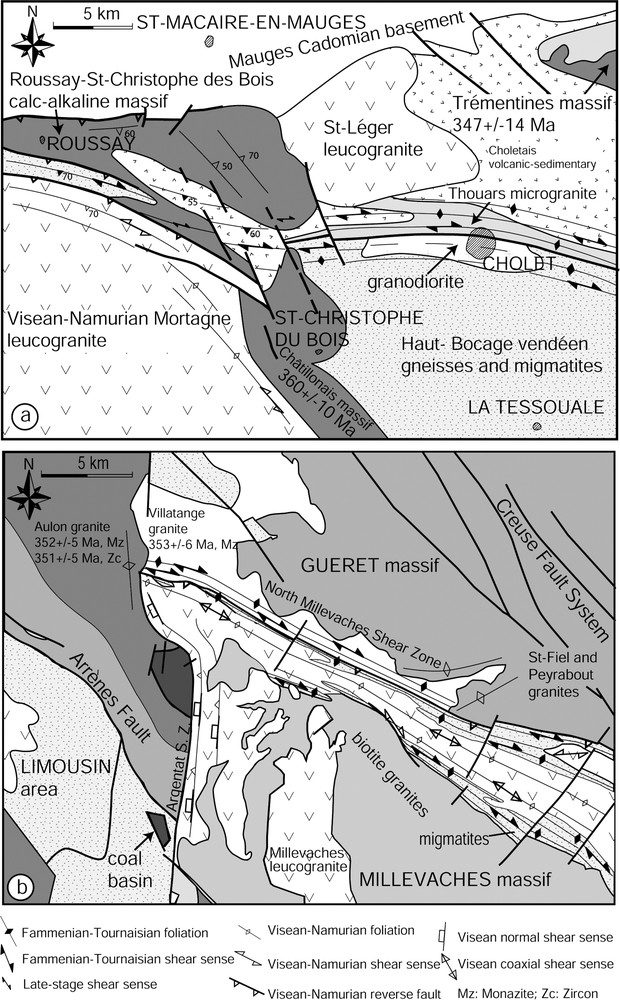

(a) Structural sketch map of the Cholet area. (b) Structural sketch map of the Guéret area.

(a) Carte structurale schématique du secteur de Cholet. (b) Carte structurale schématique du secteur de Guéret.

Le cisaillement Nord-Millevaches–La Courtine traverse les migmatites du Millevaches (Fig. 2b) et de Guéret [20,27], intrudées par les granites des massifs de Guéret et de Millevaches. Le massif de Guéret comprend [31] : la granodiorite–tonalite de Villatange, la granodiorite de Saint-Fiel, le monzogranite de Peyrabout et le leucomonzogranite d'Aulon. Le Millevaches est formé par des granites à biotite [27] et des leucogranites syn-cinématiques [12].

3 Analyse structurale et géochronologie

3.1 Le cisaillement de Cholet

Il déforme le microgranite de Thouars [19,30], ainsi que les migmatites du Haut Bocage (Fig. 2a). Le microgranite de Thouars est mylonitisé sur une zone large de 2 à 4 km, au sein de laquelle on note la présence de bandes de cisaillements dextres N120° à N140°E, portant une linéation minérale pentée de 10° vers l'est [19,24]. Le métamorphisme atteint le faciès amphibolitique en bordure du microgranite déformé [24,26,29]. Dans les migmatites de la Tessouale, le cisaillement induit des structures mylonitiques similaires.

Le massif granodioritique calco-alcalin de Roussay–Saint-Christophe-du-Bois, intrusif dans les unités des Mauges et du Haut Bocage vendéen, interrompt le couloir mylonitique du cisaillement de Cholet. Toutefois, une bande kilométrique de granodiorite modérément cisaillée dans le faciès schistes verts affecte la partie centrale du massif, dans le prolongement du cisaillement de Cholet, mais sans le décaler de façon notable.

Le massif de Roussay–Saint-Christophe-du-Bois fait partie d'un ensemble d'intrusions calco-alcalines s'étendant du Massif central à l'unité des Mauges [10,11]. Ces intrusions sont datées par la méthode U/Pb et donnent un âge moyen de [5]. Ces datations montrent que l'essentiel du rejet était réalisé à la fin du Tournaisien.

Le microgranite de Thouars, resté en domaine supracrustal, n'a pu pas être mylonitisé en contexte amphibolitique sans un apport de chaleur conséquent. Cet apport de chaleur est mis en relation avec l'accolement par le cisaillement des migmatites encore chaudes du Haut Bocage. La limite inférieure du cisaillement est donc donnée par l'âge des migmatites datées par la méthode UPbTh sur monazite à [26].

En conclusion, le rejet principal du cisaillement de Cholet se produit entre l'anatexie au Frasnien et la mise en place du massif de Roussay–Saint-Christophe-du-Bois, vers la fin du Tournaisien.

3.2 Le cisaillement Nord-Millevaches–La Courtine

Cette zone de cisaillement ductile de 2 à 6 km de large affecte du nord au sud : (1) la granodiorite de Villatange, (2) les migmatites du massif du Millevaches, (3) des leucogranites viséo-namuriens intrusifs dans les migmatites du Millevaches (Fig. 2b).

En bordure du massif de Guéret, la lame de granodiorite de Villatange montre des bandes de cisaillement dextres N120°E verticales, portant une linéation minérale horizontale. La mise en place de ce granite est syncinématique [14]. Le cisaillement est recoupé au nord-ouest par le leucomonzogranite d'Aulon, et au sud-est par les granites de Saint-Fiel et de Peyrabout. La mise en place de ces plutons scelle donc le cisaillement dextre.

Dans les migmatites, la mylonitisation montre des plans de cisaillement dextre N120°E portant une linéation minérale pentée de 0 à 30° vers le sud-est. Ce cisaillement est contemporain d'un assemblage métamorphique amphibolitique [14,28]. Il se poursuit en contexte rétromorphique dans la zone à chlorite-muscovite [28].

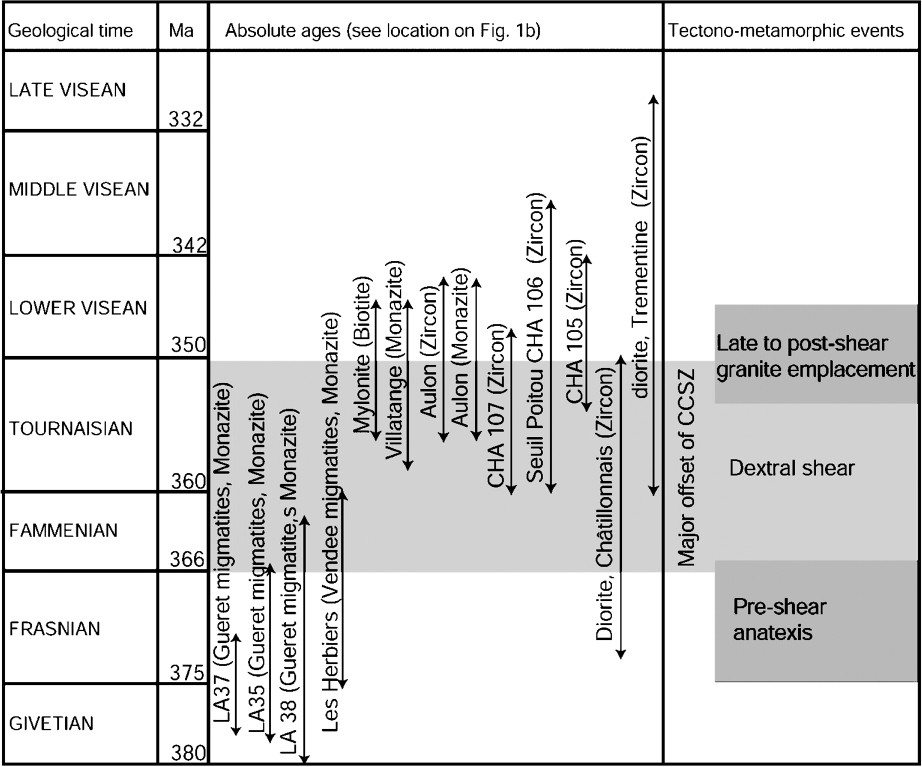

Un âge UPbTh sur monazite à sur le granite syn-cinématique de Villatange atteste le fonctionnement du cisaillement au Tournaisien. Ce cisaillement est post-daté de la fin du Tournaisien par deux âges obtenus sur le massif d'Aulon : sur monazite, et sur zircon [28]. L'âge inférieur du fonctionnement du cisaillement est donné par les datations des migmatites par la méthode UPbTh sur monazite [28] : , , , soit Frasnien (Fig. 3).

Summary of the available radiometric ages of migmatites (monazite UThPb), calc-alkaline and peraluminous granites (whole rock RbSr, monazite UThPb and zircon UPb), and mylonites (biotite 40Ar/39Ar).

Synthèse des âges radiométriques disponibles sur les migmatites (UThPb sur monazite), sur les granites calco-alcalins et peralumineux (RbSr sur roche totale, UThPb sur monazite et UPb sur zircon), et sur les mylonites (40Ar/39Ar sur biotite).

L'essentiel du rejet du cisaillement Nord-Millevaches–La Courtine est donc réalisé après l'anatexie frasnienne et avant la mise en place fini-tournaisienne des granites d'Aulon, de Saint-Fiel et de Peyrabout.

4 Discussion et conclusion

Les cisaillements de Cholet et du Nord-Millevaches–La Courtine appartiennent à un long cisaillement dextre, que nous nommons cisaillement de Cholet–La Courtine. Ce cisaillement constitue l'une des branches les plus longues du cisaillement Sud-Armoricain, et se continue par la faille ductile de Sainte-Christine [3], à l'est du Sillon houiller (Fig. 1b).

Ce cisaillement fonctionne au Famenno-Tournaisien, peu après l'anatexie régionale (378–368 Ma), et l'essentiel de son rejet est acquis lors de l'intrusion de magmas post-cinématiques à la fin du Tournaisien. Les rejeux ultérieurs du cisaillement restent mineurs et sont à l'origine de brèches le long des failles d'Arrènes [28] et d'Ouzilly [21]. Les déformations ductiles observées dans les leucogranites syncinématiques viséens du Millevaches [27] appartiennent à l'histoire tardive et enregistrent une déformation coaxiale, dont le rejet demeure négligeable [7].

Le cisaillement de Cholet accole un domaine de croûte inférieure (les migmatites du Haut Bocage) et un domaine superficiel (l'unité des Mauges). Si l'on prend en compte la différence de niveaux structuraux de ces domaines et le pitch des linéations minérales penté de 10° vers le sud-est, un rejet horizontal de 100 à 170 km doit donc être envisagé pour ce couloir mylonitique lors du Famenno-Tournaisien.

Cette étude apporte une nouvelle chronologie dans l'histoire du fonctionnement des grandes zones de cisaillements varisques ouest-européens. Le rejet majeur qui s'effectue dés le Famenno-Tournaisien devra être pris en compte dans les futurs modèles géodynamiques hercyniens.

1 Introduction

Like other collisional mountain ranges such as the Alps or the Himalayas, the Variscan orogen underwent lateral block extrusions accommodated by large-scale strike-slip shear zones [1,2,6,16]. The southern branch of the South Armorican Shear Zone (SASZ), which crosses Brittany and Vendée, is one of such shear zones. It extends eastward to the Massif Central (Fig. 1a) [8,25]. In central Brittany, several studies showed that the onset of shear deformation took place during Latest Carboniferous times (355 Ma) [15,23], continued during the Namuro-Westphalian, as attested by syn-kinematically sheared leucogranites [4,17], and ended during the Early Carboniferous (300 Ma) with the formation of syn-tectonic coal basins [23]. The aim of this contribution is to show that this timing can be significantly improved by integrating geochronological data from the southeastern extension of the SASZ in the Vendée area (Cholet Shear Zone; Fig. 2a) and in the Massif Central (North-Millevaches–La Courtine Shear Zone, NMCSZ; Fig. 2b). It results that most of the offset along the SASZ took place immediately after the Frasnian anatexis (372–368 Ma) and before the emplacement of Late Tournaisian calc-alkaline and peraluminous granites (355–350 Ma).

2 Geological outline

The synthesis of surface and subsurface data relevant to the basement rocks around or beneath the Mesozoic cover of the Seuil du Poitou (Fig. 1b) shows that the extension of the SASZ consists of the Cholet Shear Zone in South Brittany, the Ouzilly and Arrènes faults in northwestern Massif Central, and the NMCSZ further southeast [21,22,25]. Both the Cholet Shear Zone and the NMCSZ consist of amphibolite-to-greenschist-facies mylonites, whereas the Ouzilly and Arrènes faults are marked by brittle fault rocks such as cataclasites [21,28]. The Ouzilly and Arrènes faults are also locally underlined by mylonites developed in Namurian granitic intrusions [12].

The Cholet Shear Zone (Fig. 2a) juxtaposes the Mauges unit against the Haut Bocage unit. The Mauges unit consists of a Cadomian basement unconformably covered by the Choletais Cambrian and Ordovician sedimentary and volcanic deposits. The Cambrian deposits are cross-cut by the Middle Cambrian Thouars microgranite [30]. The ‘Haut Bocage’ unit consists of la Tessouale migmatites. As detailed below, both units and the Cholet Shear Zone are in turn intruded by Tournaisian calc-alkaline Roussay–Saint-Christophe-du-Bois granites.

The NMCSZ cross-cuts a stack of ductile and metamorphic nappes in the Limousin area [6,9,13,20]. This pile is cross-cut by granitic plutons belonging to the Guéret and Millevaches laccolitic complexes. The Tournaisian Guéret granitic complex is composed of several facies [31]: the Villatange granodiorite–tonalite, the Saint-Fiel granodiorite, the Peyrabout monzogranite and the Aulon leucomonzogranite. The Late Visean to Namurian North-Millevaches granitic complex (Fig. 2b) is mainly composed by biotite granites and by elongated leucogranites deformed during their emplacement [12].

3 Structural and geochronological relationships between pluton emplacement and ductile deformation

3.1 The Cholet Shear Zone

The Cholet Shear Zone affects the Thouars microgranite [19,30] and the La Tessouale migmatites (Fig. 2a). The microgranite and the migmatites are mylonitized on a width of 2 to 3 km (Fig. 1b and 2a; [19,24]). The mylonites display a N100°- to N120°E-trending vertical foliation offset by N120°- to N140°E-trending shear bands bearing a mineral lineation dipping N10°SE, indicating a dextral sense of shear. In the mylonitic microgranite, the metamorphic grade culminates in amphibolitic conditions close to the centre of the shear zone and decreases in greenschist facies conditions with increasing distance from the fault [26,29,30].

As stated above, the calc-alkaline Roussay–Saint-Christophe-du-Bois granodioritic pluton intrudes the Mauges and Haut Bocage units (Fig. 2a). It cross-cuts the mylonitic zone of the Cholet Shear Zone. Furthermore, its central part includes a plurikilometric scale xenolith composed of ductilely deformed Cambrian Choletais deposits. The ductile deformation in amphibolite facies condition preserved in the xenolith is not observed in the host granodiorite. Moreover, contact metamorphism in the xenolith overprints the metamorphism linked with the mylonitization [19]. The Roussay–Saint-Christophe-du-Bois granodiorite experienced moderate mylonitization under greenschist facies conditions. The kilometre-wide mylonitic zone, which is located in the continuation of the Cholet Shear Zone, crosses the pluton in its central part, but without significantly offsetting it.

The calc-alkaline Roussay–Saint-Christophe-du-Bois granodiorite belongs to the calc-alkaline intrusive series extending from the Mauges unit to the northwestern Massif Central (Fig. 1b; [10,11]). Though no radiometric ages of the Roussay–Saint-Christophe-du-Bois granodiorite are available, radiometric datings of nearby plutons from the similar calc-alkaline series yielded a whole rock RbSr age of [19] and zircon UPb ages ranging from to (Fig. 3, [5,25]). The mean age derived from all these datings is , i.e. Tournaisian [5]. Given this age consistency, a similar age of about 355 Ma can be inferred for the Roussay–Saint-Christophe-du-Bois granodiorite. It follows that most of the offset along the Cholet Shear Zone was likely achieved before about 355 Ma.

Because of its upper crust emplacement, the Thouars microgranite could not have been mylonitized in amphibolite facies conditions without heat supply. A significant heat supply could have been brought by the juxtaposition of the still hot La Tessouale migmatites. Radiometric dating of the La Tessouale migmatites by the UThPb on monazite yielded an age of [26]. This age can be considered as the age of onset of deformation along the Cholet Shear Zone.

It results that most of the displacement along the Cholet Shear Zone was achieved after the Frasnian anatexis (about 368 Ma) and the Tournaisian emplacement of the Roussay–Saint-Christophe-du-Bois granodiorite (about 355 Ma), that is during the Fammenian–Tournaisian.

3.2 The North-Millevaches-La Courtine Shear Zone (NMCSZ)

In the Guéret area, the 2-to-6-km-wide NMCSZ deforms successively, from the northwest to the southwest (Fig. 2b): (1) the Villatange granodiorite, (2) the Millevaches migmatites, (3) the Late Visean to Namurian North-Millevaches leucogranites intrusive in the Millevaches migmatites.

To the south of the Guéret complex, the elongated Villatange granodiorite pluton experienced ductile deformation (Fig. 2b). The hand samples show N120°E-trending shear bands bearing a horizontal mineral lineation and indicating a dextral sense of shear. Quartz lattice preferred orientation shows that the deformation occurred during the Villatange granite emplacement [14]. The mylonitic migmatites and the mylonitic Villatange granodiorite are cross-cut by the undeformed Aulon leucomonzogranodiorite (Fig. 2b). Field observations and mapping show a clearly intrusive contact between Villatange and Aulon plutons and a lack of any faults or mylonitic zones. Similarly, further southeast, the NMCSZ is cross-cut by the undeformed Saint-Fiel and Peyrabout plutons. The Millevaches migmatites-derived mylonites display a N90°- to N110°E-trending vertical foliation offset by N120°-trending shear bands bearing a mineral lineation raking 0 to 30°SE, indicating a dextral sense of shear. The mylonitization occurred first in amphibolite facies conditions and then evolved in greenschist facies conditions [14,28]. In the central part of the NMCSZ, a strip of Late Visean to Namurian North-Millevaches leucogranites has recorded only a coaxial deformation consistent with a negligible offset [7].

A monazite UThPb age of age obtained on the Villatange granodiorite (Fig. 3) testifies to a dextral shear during the Tournaisian. A monazite UThPb age of and a zircon UPb age of obtained in the undeformed Aulon leucomonzogranite give a minimum age of activity of the NMCSZ [7,28]. This age is also supported by a biotite 40Ar/39Ar age of obtained on a mylonite located along the la Courtine Shear Zone (Fig. 1b) and interpreted as the age of the end of shearing (cooling below 350 °C, [14]).

The maximum age of shearing along the NMCSZ is given by monazite UThPb ages of about 372 Ma, that is Frasnian, obtained on Guéret migmatites (Fig. 3, [28]): 373 ± 5 Ma (LA35), 376 ± 2 Ma (LA37), 371 ± 8 Ma (LA38).

It follows that most of the displacement along the Cholet Shear Zone was achieved between the Frasnian anatexis (about 372 Ma) and the Tournaisian emplacement of the Aulon, Saint-Fiel and Peyrabout plutons (355–350 Ma).

It arises from the above data and geochronological constraints that most of the displacement along the NMCSZ took place between the Frasnian anatexis (about 372 Ma) and the Tournaisian emplacement of the Guéret granites (355–350 Ma), that is during the Fammenian–Tournaisian.

4 Discussion and conclusion

This study shows that the Cholet Shear Zone of southern Brittany can be correlated with the NMCSZ in the western Massif Central. This newly labelled Cholet–La Courtine Shear Zone, which constitutes one of the largest branches of the SASZ, probably extends, with a 70-km sinistral offset, to the east of the ‘Sillon houiller’, to the Sainte-Christine Fault [3].

Inception of the right-lateral offset along the Cholet–La Courtine Shear Zone occurred immediately after the Late Devonian regional anatexis event dated at 378–368 Ma. Most of the offset was achieved at the end of the Tournaisian before the emplacement of calc-alkaline plutons in Vendée and of peraluminous plutons of the Guéret complex.

These late intrusions, along with Visean and Namurian leucogranites, account for the apparent discontinuity of the Cholet–La Courtine Shear Zone. Visean to Namurian deformation of the Cholet–La Courtine Shear Zone consists either of brittle shear along the Arrènes and Ouzilly faults [21,27] or of ductile deformation recorded by the Brame-Saint-Sylvestre and North-Millevaches leucogranites (Figs. 1b and 2b).

Unlike the NMCSZ that crosses a migmatitic domain (Guéret and Millevaches migmatites, [18,27]), the Cholet Shear Zone juxtaposes two contrasted structural domains: the northern domain, the Mauges unit, remained in the upper crust since the Cambrian; to the contrary, the ‘Haut Bocage’ unit (La Tessouale migmatites) was uplifted from the lower crust (between 20 and 30 km [19]). The Cholet Shear Zone does not display any evidence for ductile or brittle vertical displacement (e.g., vertical lineations or striations). Given the 20- to 30-km depth contrast between the two sides of the fault and the 10°SE rake of the mineral lineation, a horizontal offset ranging from 100 and 170 km can be inferred along the Cholet Shear Zone during the Fammenian–Tournaisian.

This study provides a new chronology of the displacement history of major ductile shear zones of the western European Variscan belt. These shear zones were active as earlier as the Fammenian–Tournaisian. The corresponding right-lateral horizontal offset has to be taken into account in any geodynamical reconstruction of the Variscan belt.

Acknowledgements

Comments by M. Faure helped improve the manuscript.