Version française abrégée

1 Introduction

Le rotationnel de la force d'entraînement du vent à la surface de l'eau, que l'on nommera par la suite rotationnel , est un agent fondamental de forçage pour les processus océaniques dynamiques. Il contrôle le « pompage d'Ekman » et l'advection verticale associée, dans les régions où il n'existe pas d'effet de côte. Ces mouvements verticaux ont des conséquences physiques, chimiques et biologiques sur l'écosystème océanique.

Avant 1991, de rares mesures du rotationnel ont été effectuées à partir de mesures en mer en vue d'améliorer les modèles océaniques et ont montré que la taille de la grille utilisée pour estimer ce paramètre à partir de données de vent est déterminante. En effet, les calculs à grande échelle surestiment de manière significative l'amplitude du rotationnel. Avant 1991, les grilles les plus fines étaient supérieures à 1° de résolution en latitude et en longitude.

Au lancement du satellite ERS-1, en 1991, la relation empirique entre section efficace de rétrodiffusion et champs de vent était mal connue. Dans une première approche, la relation entre la section efficace de rétrodiffusion du diffusiomètre équipant les satellites ERS-1 et ERS-2, et la valeur moyenne du rotationnel a été étudiée, et des structures océaniques à mésoéchelle (0–100 km, 1 semaine) ont été identifiées dans le Sud-Ouest de l'océan Indien.

2 Données

Le diffusiomètre ERS-1 a fonctionné de façon continue entre juillet 1991 et mars 2000, transmettant et recevant des signaux, avec une polarisation verticale et une fréquence de 5,3 GHz. La section efficace de rétrodiffusion était échantillonnée avec une résolution spatiale de 25 km dans 19 cellules réparties en fauchée et avec une résolution temporelle de 3 j. Pour une couverture exhaustive de la zone d'étude, il est nécessaire d'acquérir 18 passages environ, ce qui correspond à une plage de temps nécessaire de 9 j. Pour cette étude, la base de données comporte seize millions d'enregistrements regroupant la latitude, la longitude, la vitesse et la direction du vent de la section efficace échantillonnée sur une zone située au sud-ouest de l'océan Indien (Fig. 3) entre janvier et décembre 1994.

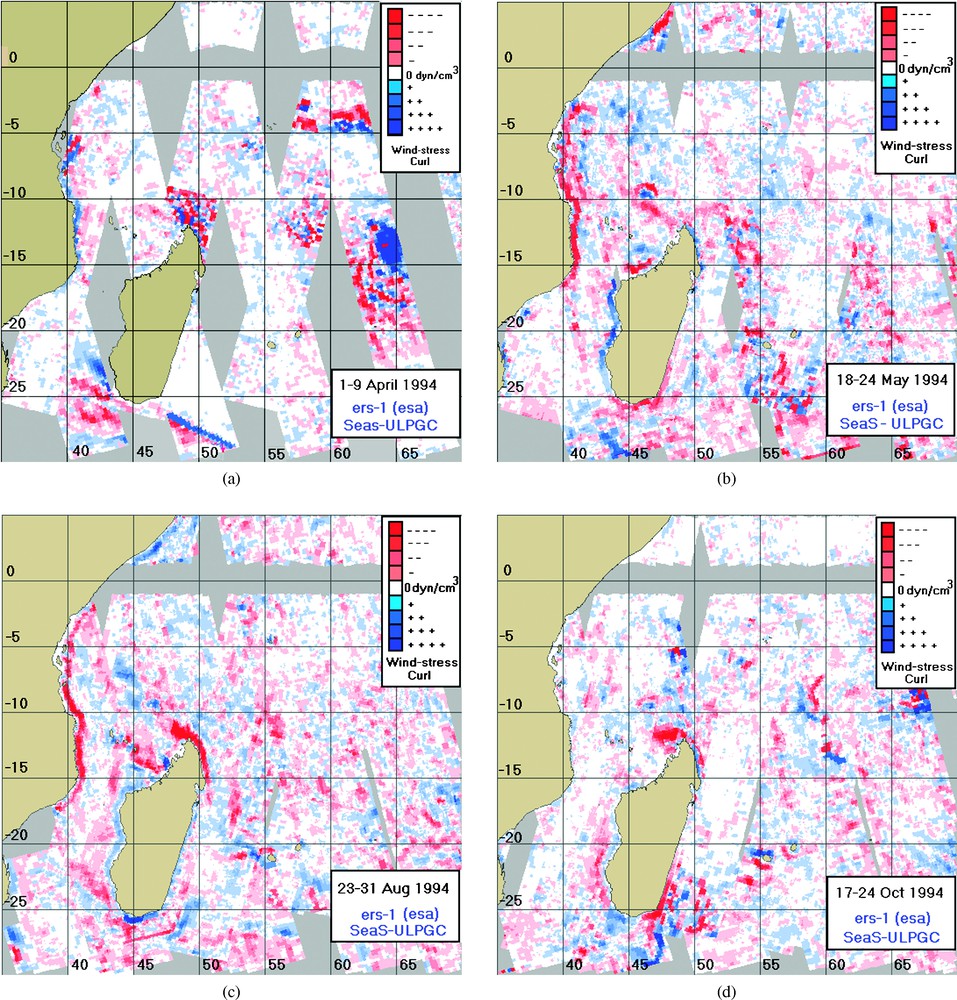

Wind-stress curl (dyn/cm3) in the southwestern Indian Ocean. The range of the wind-stress curl is between −0.5×10−6 (strong red) and 1×10−6 (strong blue). (a) Between 1 and 9 April 1994 (400 000 data). (b) Between 18 and 24 May 1994 (400 000 data). (c) Between 23 and 31 August 1994 (400 000 data). (d) Between 17 and 24 October 1994 (400 000 data).

Rotationnel de la force d'entraînement du vent (dyn/cm3) dans le Sud-Ouest de l'océan Indien. Le rotationnel de la force d'entraînement du vent varie entre −0.5×10−6 (rouge foncé) et 1×10−6 (bleu foncé). (a) Entre le 1er et le 9 avril 1994 (400 000 données). (b) Entre le 18 et le 24 mai 1994 (400 000 données). (c) Entre le 23 et le 31 août 1994 (400 000 données). (d) Entre le 17 et le 24 octobre 1994 (400 000 données).

3 Méthode

Avant d'être analysées, les données sont filtrées afin de garantir des valeurs physiquement possibles. Le rotationnel est calculé à partir de l'équation de mouvement ramenée en unité de masse et l'équation de continuité (1). Après différenciation et regroupement, le pompage d'Ekman extrait par l'Éq. (2). La force d'entraînement du vent est estimée à partir de valeurs individuelles du vecteur vent, issues des données ERS-1 (3).

Des grilles de de résolution sont établies sur l'océan Indien afin de couvrir les structures océaniques de la région sud-ouest. La résolution de est maintenue pour le calcul du rotationnel. Une distribution composite à mésoéchelle est ensuite construite en moyennant les passages ascendants et descendants à l'intérieur de chaque carré de pour des périodes de 9 j.

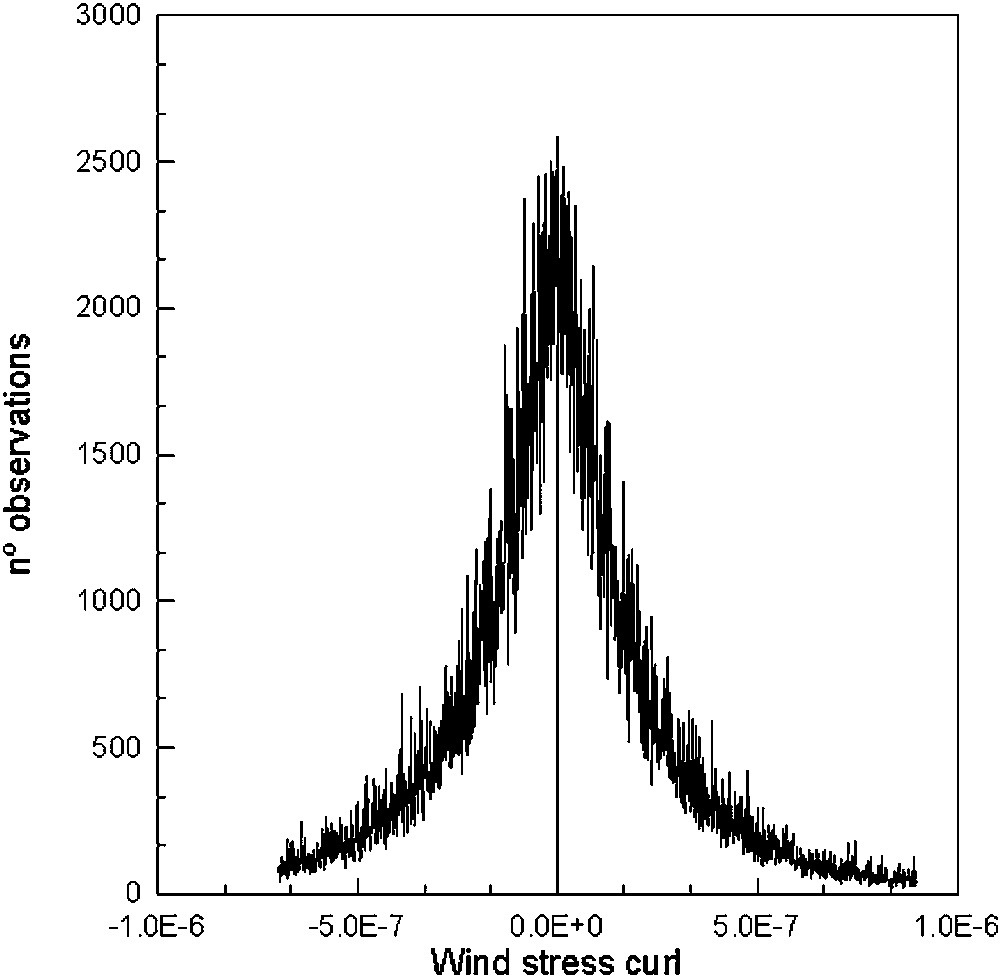

Les amplitudes du pompage d'Ekman calculées ont un mode qui tend vers 0 et contient relativement peu d'observations supplémentaires (Fig. 1). En outre, la comparaison de différents échantillons indique une dépendance avec la saison.

Occurrences of wind-stress curl (dyn/cm3) in the southwestern Indian Ocean for the whole period (January–December 1994) (18 million points).

Occurrences du rotationnel de la force d'entraînement du vent (dyn/cm3) au Sud-Ouest de l'océan Indien pour toute la période considérée (janvier–décembre 1994) (18 millions de données).

Les cartes étant fortement bruitées, le bruit d'échantillonnage est réduit en appliquant un filtrage spatial sur points de grille. La valeur en chaque point de grille est ainsi remplacée par la médiane des quatre valeurs dans la fenêtre centrée sur cette position. Afin de faciliter l'interprétation des distributions, une échelle à deux couleurs du bleu (positif) au rouge (négatif) est utilisée.

4 Résultats et interprétation

Ce processus est appliqué indépendamment à chaque jeu de données sur 9 j (9 orbites ascendantes et 9 orbites descendantes) pour toute l'année 1994. Les cartes obtenues sont représentées sur les Figs. 3 et 4. Elles montrent une prépondérance de rotationnels anticycloniques et cycloniques dans le Sud-Ouest de l'océan Indien (Fig. 2). Les cyclones tropicaux sont des phénomènes atmosphériques à mésoéchelle et induisent aussi des structures océaniques remarquables. Ils engendrent des valeurs élevées dans l'ensemble des séries. Sur la Fig. 3a, l'œil et la structure circulaire compacte du cyclone Odille apparaissent clairement sous forme d'un fort rotationnel cyclonique. Au fil des mois, des événements identifiés sont interprétés selon les structures océaniques connues dans cette région [14] et suivis sur les différentes cartes (Figs. 3 et 4). Entre mars et avril 1994, de forts rotationnels cycloniques, localisés le long de la côte sud-est de l'Afrique et au sud-est de Madagascar, sont associés à des upwellings côtiers intenses, générés par l'alternance de vents soufflant de l'Équateur et du Sud au-dessus du canal de Mozambique. Entre mai et août 1994, la distribution cyclonique du rotationnel est plutôt faible près de la côte sud-est de Madagascar (Fig. 3b et c). Un upwelling côtier, caractérisé par un rotationnel cyclonique intense, est visible près de la côte sud-ouest de Madagascar sur une grande partie des séries (Fig. 3). Un rotationnel anticyclonique (positif) est aussi observé le long de la côte du Mozambique et au sud-est de Madagascar. Une structure étendue est présente une grande partie de l'année le long de la côte du Mozambique, au sud-ouest et au sud-est de Madagascar. Elle indique que la divergence et la convergence d'Ekman dominent alternativement près des côtes sud-est. La zone de transition entre les régions de rotationnels cycloniques et anticycloniques est située le long du canal de Mozambique.

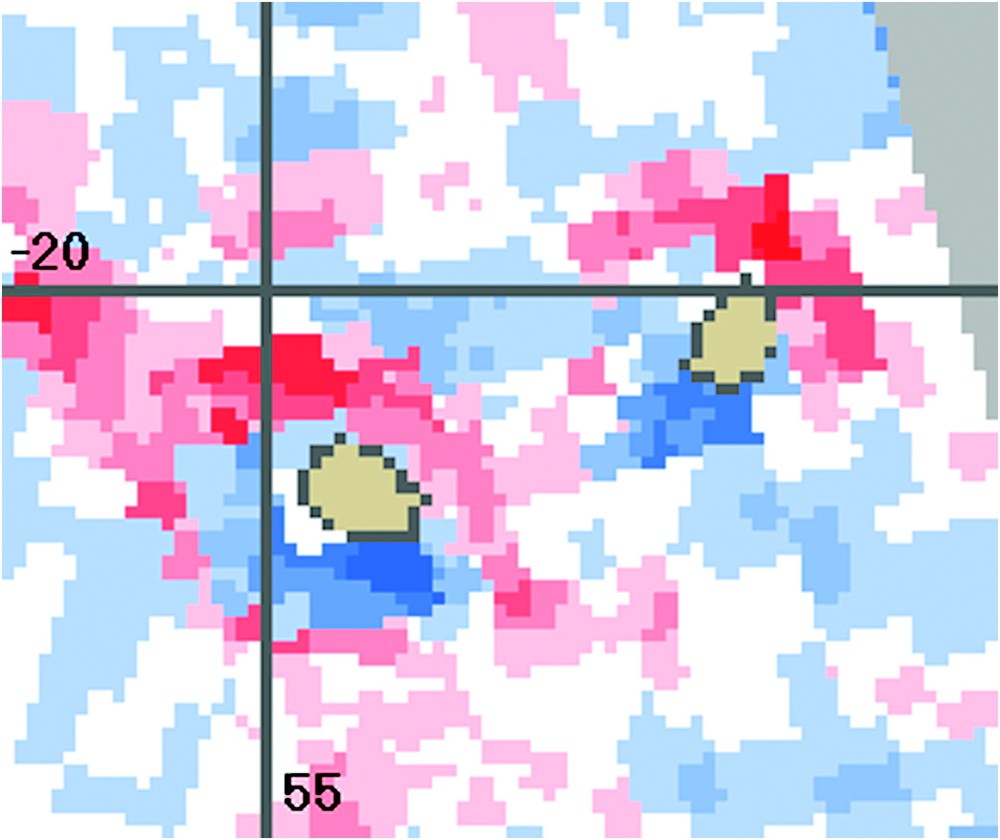

Wind-stress curl (dyn/cm3) in Reunion and Mauritius Islands between 23 February and 4 March 1994. The range of the wind-stress curl is between −0.5×10−6 (strong red) and 1×10−6 (strong blue).

Rotationnel de la force d'entraînement du vent (dyn/cm3) à La Réunion et à l'île Maurice entre le 23 février et le 4 mars 1994. Le rotationnel de la force d'entraînement du vent varie entre −0,5×10−6 (rouge foncé) et 1×10−6 (bleu foncé).

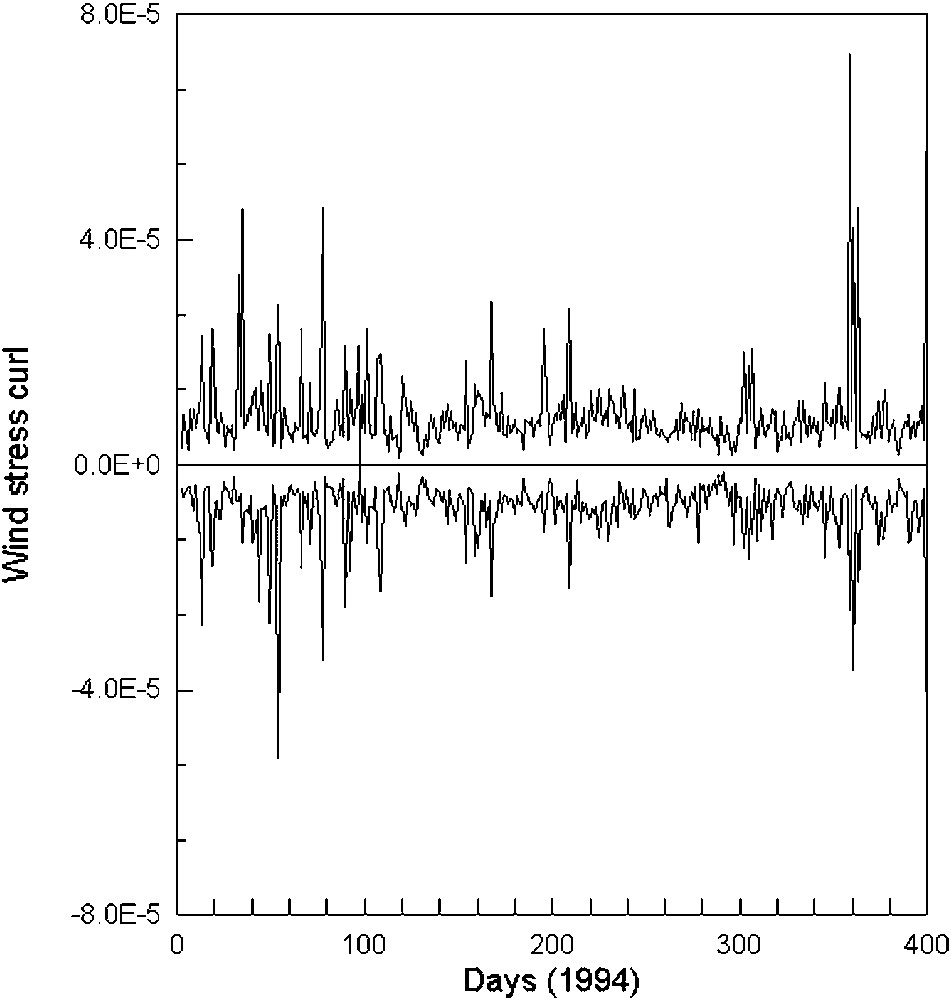

Time sequence plot for the maxima and minima wind-stress curl records (dyn/cm3) in the southwestern Indian Ocean for the whole period (January–December 1994).

Évolution temporelle des maxima et des minima du rotationnel de la force d'entraînement du vent (dyn/cm3), enregistrés dans le Sud-Ouest de l'océan Indien pour toute la période considérée (janvier–décembre 1994).

Hormis la présence de cyclones à l'échelle synoptique, qui modifient de manière intermittente le régime général, le Sud-Ouest de l'océan Indien est caractérisé par un rotationnel cyclonique correspondant à des zones d'upwelling côtier au sud-ouest de Madagascar et le long des côtes du canal de Mozambique. À différents endroits, tels que l'Est de Madagascar et du Mozambique, des lobes distincts ou des contours isolés de rotationnel anticyclonique apparaissent dans des régions de convergence. La structure littorale en jet au nord et au sud de Madagascar, ainsi qu'au nord et au sud de La Réunion et de l'île Maurice, est expliquée comme une réponse de la couche limite au blocage des alizés par les montagnes.

5 Conclusion

Cette étude montre qu'en travaillant à une résolution de , le rotationnel de la force d'entraînement du vent, déduit des données du diffusiomètre ERS-1, est suffisamment sensible pour étudier la dynamique du Sud-Ouest de l'océan Indien et en particulier identifier des phénomènes océaniques à la mésoéchelle.

1 Introduction

The curl of the wind stress acting on the sea surface is a fundamental forcing agent for dynamical ocean processes. It stands out as the external input term in ocean model formulations expressed in terms of vorticity balance. From the viewpoint of vertical structure in the flow field, the influence of the wind-stress curl appears as the divergence of the surface Ekman transport. Wind-stress curl thus controls ‘Ekman pumping’ and associated vertical advection in regions seaward of the immediate effects of coastal boundaries and so may have a variety of physical, chemical, and biological consequences to the ocean ecosystem [1,2,9,13,15]. Potential mechanisms include rearrangements of the mass field and corresponding changes in the current structure, generation of baroclinic Rossby waves, and other significant contributions to variability in the coastal ocean on shorter space and time scales [7,11,16,17,22].

No measurements of wind-stress curl were available before 1991 (when the ERS-1 spacecraft was launched), except in rare instances where arrays of research ships or buoys were used to make coordinated wind measurements to construct wind-stress field in order to improve the accuracy and range of numerical oceanic models on intermediate space and time scales [4]. Thus, the effects of grid size on calculations of wind-stress curl are demonstrated in [20]. The author also suggested that large-scale calculations significantly underestimate the curl magnitude. The finest-scale distributions of the mean wind-stress curl were based on computational grids with 1° latitude/longitude resolution.

The microwave scatterometer was launched onboard the ERS-1 spacecraft in July 1991, and it operated continuously until March 2000, transmitting and receiving vertically polarized signals at 5.3 GHz with a spacing of 25 km in 19 cells over the swath width with a high temporal repetition rate (3 days) [3]. There was considerable uncertainty in the empirical relationship between the backscatter cross-section and the wind field. This uncertainty was due to three factors: (1) limited high-quality direct wind measurements; (2) wind retrieval model variability; and (3) scatterometer measurement biases and variability. However, after 24 February 1993, empirical models based on observed winds denoted CMOD3 and CMOD4 [12,21] and developed for the European Space Agency (ESA) have been used to obtain the wind vector product with a sufficient quality and quantity [18]. The spatial structure of the winds are studied in [23] through the Ekman pumping field, derived from the curl of the wind-stress field. This has been computed by a boundary layer model, using scatterometer wind data, sea-surface temperature from the ERS-1 ATSR and the NOAA AVHRR radiometers and air temperature, humidity and atmospheric pressure.

In this study, we calculate the Ekman pumping with a model more compact than that presented in [23] in the sense that we do not use a boundary layer model to correct for stability the original scatterometer winds. A scale of 25 km is considered for investigating the ERS-1 scatterometer backscatter cross-sections dependence on mean wind-stress curl. Mesoscale (0:100 km, monthly) oceanographic features are identified by their appearance in the sea surface of the southwestern Indian Ocean.

2 Methodology

2.1 Space craft measurements

The right-looking ERS-1 scatterometer utilizes three antenna beams at angles oriented at 45° (fore-beam), 90° (mid-beam) and 135° (aft-beam) with respect to the spacecraft direction of travel. The nominal resolution is in a horizontal plane observed over a swath width of 500 km beginning at 225 km from the spacecraft nadir projection.

The cross-section was sampled at a spacing of 25 km in slots () over the swath-width with a high temporal repetition rate (3 days) for ascending and descending overpasses in the southwestern Indian Ocean (Fig. 3). For exhaustive cover of our test area, 18 passes have to be acquired. They correspond to 216 slots of and to an acquisition period of 9 days. The cross-sections were then archived into a combined data set (16 million records) which included the latitude, longitude, wind speed and wind direction of the cross-section sampled on the southwestern Indian Ocean between January and December 1994. Before proceeding with the data analysis, a filter was used to ensure physically possible values.

2.2 Background

To make deductions of remotely-sensed wind-stress curl, mathematical statements on the form of the forces are written; then solutions are attempted according to the technical limitations of the satellite-derived data.

The equation of motion per unit of mass for the components are written as two component equations. The coordinates x and y and their respective velocity components are positive in the east, north and upward directions respectively and the origin of coordinates are at the sea surface as:

| (1) |

After cross differentiating and reordering Eq. (1) and considering the continuity equation, the Ekman pumping related to the curl of the wind-stress field is calculated as:

| (2) |

2.3 Data processing and computational procedures

Various errors (classified as being either systematic or random) may introduce uncertainties into the quantities appearing in Eq. (2) [4].

The horizontal components of wind stress, τ, are computed from individual wind values according to the bulk aerodynamic formula:

| (3) |

Systematic errors due to the inadequacy of the bulk formulation approach are hard to assess [10]. Another type of uncertainty is the use of a constant drag coefficient in the stress computation. The value of is dependent on both wind speed and atmospheric stability. However, there is no universally adopted variable formulation for at the present time. Hence, this particular issue was avoided by computing the linear relationship with the wind speed.

A problem greater than systematic errors was the random inherent imprecision resulting from the geographic errors and the scatter in marine weather reports. The ERS-1 scatterometer and the ERS-2 scatterometer have been operating from July 1991 to March 2000 and since February 1996, respectively, and thus some years of fully calibrated data are presently available. This important dataset acquired over the entire ocean offers a unique opportunity to assess the contribution of the coarse resolution active microwave system to monitor the sea surface, through reduction of the systematic and random errors with increasing numbers of observations incorporated in the calculation.

Grids of 25-km latitude/longitude quadrilaterals were established along the Indian Ocean, so as to cover the general oceanographic features of the southwestern region. A resolution was maintained to compute the curl. A composite mesoscale distribution was then constructed by averaging successive ascending-descending overpasses within each square over each one of the 9-days segments of the annual cycle of 1994.

Eq. (2) was solved by the method of the finite difference, and being the averages of the wind-stress component estimates in the four kilometres summary areas involved in a given calculation. Magnitudes of the Ekman pumping tend to have a mode near 0 and contain relatively few exceeding observations (Fig. 1). Comparisons among differently constituted subsamples indicate some degree of dependence on season. In winter (January to February 1994) over the southern hemisphere, mesoscale cyclones may yield slightly maximum values (Fig. 2).

2.4 Construction of the wind-stress curl fields

A decision was made to deal with the sampling noise through analysis and smoothing, while attempting to retain the finest scale of significant features available at any location. Thus, independent single-week (9 days) mean distributions of wind-stress curl were prepared and subjected to a spatial smoothing. A gridpoint whereby the value at each grid location was replaced by the median of the four values in the grid segment centred at that location was employed. The grid indexing was set up in such a way that the zonal grid coordinate was referenced to the WGS 84 provided by NASA [8]. The filter rectangles were distorted into a parallelogram shape with the sloping sides oriented parallel to the ascending–descending overpasses. These filtered maps provided a fairly smooth, organized background. To aid interpretation of the wind-stress curl distributions, a single two-colour scale from blue (positive) to red (negative), indicating magnitude for each gridpoint and providing a readily referenced estimate of the reliability of each computed value, was utilized. The entire process was applied independently to each 9-day sample set (nine ascending and nine descending overpasses) for the entire period (1 January to 31 December 1994). The maps presented in Figs. 3 and 4 are, thus, based on values as independent from one another as possible, in spite of the subjective aspects of their construction. No after the fact recontouring has been performed to bring indicated features into better conformity.

3 Results

Satellite-derived results exhibited a similar general dominance of anticyclonic and cyclonic wind-stress curl over the southwestern Indian Ocean (Fig. 2). Tropical cyclones are mesoscale atmospheric phenomena and also induce remarkable oceanographic patterns. They conform to a classification [5] and yield slightly maximum values of the whole series. In Fig. 3a (1 to 9 April 1994), the major synoptic atmospheric event that occurred over the area was the Odille synoptic-scale cyclone. Odille emerged in the eastern Indian Ocean and concentrated into a cyclonic storm on 8 April 1994 near 15°S/65°E. Moving in a southwestward direction, it attained hurricane intensity on 11 November and was centred near 15°S/55°E over Madagascar, Reunion and Mauritius Islands. For this period, the ERS-1 scatterometer almost passed over the centre of the cyclone, tracking about 2800 wind vectors. The inflow on the southern side, the eye of the cyclone, and the compact circular structure are evident from the strong cyclonic wind-stress curl in this image.

Related to the regional oceanic well-known features [14], as the season progressed (March to April 1994), strong cyclonic curl maxima were located across the southeastern coast of Africa and southeastern Madagascar. They are associated with vigorous coastal upwelling generated by the alternating equatorward and southward wind fields blowing over the Mozambique Channel. Near the southeastern coast of Madagascar, however, the mean cyclonic curl distribution is rather weak during spring-summer (May to August 1994). A coastal upwelling characterized by a strong blue wind stress cyclonic curl was evident adjacent to the southwestern coast of Madagascar during a large part of the series (Fig. 3b: 18–24 May 1994, Fig. 3c: 23–31 August 1994, Fig. 3d: 17–24 October 1994). Anticyclonic curl, however, occurred parallel to the Mozambique coastline and to the southeastern coast of Madagascar. The large event extending parallel to the coastline of Mozambique, Southwest Madagascar and Southeast Madagascar was a feature present for the most of the year, indicating that Ekman divergence and convergence alternatively dominate at the ocean surface near the southeastern coasts. The transition zone between the region of cyclonic and anticyclonic curl is located along the Mozambique Channel.

The local curl maxima observed during the entire period (Fig. 3b and c) appear as different intense and meandering large lobes extended offshore anticyclonic (North Madagascar) and cyclonic (South Madagascar) curl. North Madagascar evidences a persistent, elongated lobe of anticyclonic curl (Fig. 3b). This feature appears to be aligned along the axis of the northwestward wind, which veers equatorward away from the coast in that area. South Madagascar, however, evidences a coastal cyclonic wind-stress curl found in all independent weekly distributions. It appeared as a wedge extending offshore toward the southwest, possibly generating a mesoscale cold eddy field.

Moreover, the strong tendency of the wind-stress curl signal (both cyclonic and anticyclonic curl) to decrease with distance from the coast was also evident at shorter spatial scales. A maximum of cyclonic (north) and anticyclonic (south) curl was associated with the mesoscale perturbation of the normal flow of the wind fields by the island systems (Fig. 4: 23 February to 4 March). North and South of Reunion and Mauritius Islands exhibited a similar general dominance of anticyclonic and cyclonic curl, respectively, as observed at larger scale in Madagascar (Fig. 3b).

4 Discussion

One of the purposes of the study was to check satellite-derived ERS-1 wind-stress curl distributions, which had never been used in diagnosing the dynamics of the southwestern Indian Ocean. The unsmoothed weekly distributions in this region have a particularly noisy appearance.

In spite of the mesoscale cyclones (January–April 1994) that intermittently broke the regime trend and that may yield slightly greater maxima for the whole series, the southwestern Indian Ocean is characterized by cyclonic wind-stress curl that corresponds with the coastal upwelling zones over southeastern Madagascar and the coasts of the Mozambique Channel. The coastal cyclonic curl of southeast Madagascar tended to have its greatest alongshore extent during the summer season in the southern hemisphere. Thus, the coastal upwelling that occurs within several tens of kilometres of the coast was augmented by upward Ekman pumping over a much larger extent 150 to 250 km offshore. In various locations, such as eastern Madagascar and Mozambique, distinctive lobes, or isolated patches of anticyclonic curl, appeared either in contact with, or within several hundred kilometres of the coastal boundary where coastal downwelling occurs.

The alongshore jet structure off North and South Madagascar and off North and South Reunion and Mauritius Islands has been identified as a boundary layer response of the large-scale zonal westerlies to blocking by the coastal mountain range along the southwestern Indian Ocean island system. Some authors [6,19] also indicate that the land-ocean stress gradient reinforces the jet structure and, thereby, an intensification of the alongshore wind near the coast during the winter season in the southern hemisphere.

Thus, satellite-derived scatterometer ERS-1 wind-stress curl data show that ERS-1 databases are sensitive enough to identify mesoscale underlying factors affecting ocean dynamics at a () scale.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank ESA/ESRIN for providing the scatterometer data used in the present study within the framework of a Pilot Project. We thank Dr Phillipe Lena, Dr Laurent Dagorn, Dr Manuel Cantón and Mr Andry Williams for fruitful discussions on previous draft. Special thanks are given to Mr Alberto del Campo, Mr Mamy Rakoto and Mr Xavier Bernardet for their technical assistance. This work was sponsored in part by the ‘Institut de recherche pour le développement’ (IRD–SEAS), France, and by the Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (ULPGC), Spain.