Version française abrégée

Introduction

L'obsidienne des sites néolithiques de Méditerranée occidentale et de ses abords provient, comme l'ont montré depuis longtemps les datations par traces de fission [4] et analyses géochimiques, des îles de Lipari, Palmarola, Pantelleria et du complexe volcanique sarde du Monte Arci (Fig. 1). Les « sources » d'obsidienne utilisées par les néolithiques sont parfois les gisements primaires de l'obsidienne, où elle est incluse dans sa roche mère. Elles sont plus souvent des gîtes sub-primaires, provenant de la désagrégation des précédents, où l'obsidienne est présente sous forme de blocs, galets, etc., ou secondaires, parfois situés à de grandes distances et impliquant divers modes de transports naturels. Alors qu'à Lipari toutes les obsidiennes disponibles au Néolithique présentent la même composition [9,19], on en distingue trois types à Palmarola [29] et cinq à Pantelleria [10], où cependant deux sources primaires seulement sont connues. En Sardaigne, l'analyse par activation neutronique reconnaît trois types d'obsidiennes [11,18], alors que les déterminations en mode destructif par fluorescence de rayons X [17] ou à la microsonde électronique opérant en dispersion de longueur d'ondes (EMP) permettent une division du groupe SB en deux entités discrètes, SB1 et SB2 [14,24]. D'autres subdivisions, comme celles des obsidiennes SB1 en trois sous-types [25] et des obsidiennes SC en deux sous-types [9], ne présentent pas d'intérêt en archéologie, du fait que leurs sources primaires sont très proches les unes des autres et que, dès les sources sub-primaires, plus facilement accessibles, des éléments de ces sous-types sont mêlés [25].

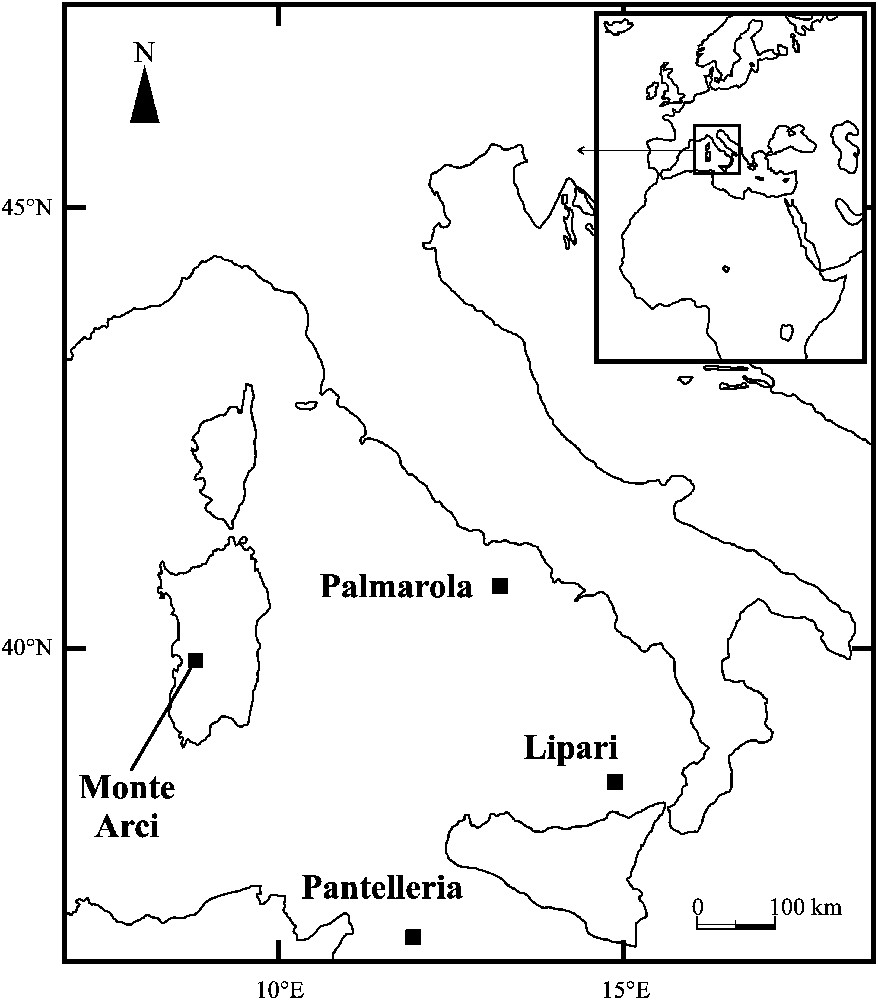

Schematic map showing the source-islands of the western Mediterranean obsidians.

Carte schématique montrant la localisation des îles-sources des obsidiennes de Méditerranée occidentale.

L'obsidienne du Monte Arci a très largement diffusé dès le VIe millénaire avant notre ère en Sardaigne et au nord de cette île, de l'Italie à la France méridionale. Comme il est difficile de distinguer optiquement toutes les obsidiennes sardes, l'intervention de méthodes instrumentales pour distinguer les types SA, SB1, SB2 et SC est nécessaire. Nous montrons ici qu'un microscope électronique à balayage équipé d'un spectromètre en dispersion d'énergie (MEB–EDS) peut, contrairement à une affirmation antérieure [24], parfaitement remplir ce rôle.

Échantillonnage et procédures expérimentales

Quatre-vingt-dix-neuf obsidiennes de composition élémentaire et/ou d'origine déjà connues ont été sélectionnées : huit provenant de Lipari et de Pantelleria, analysées par MEB–EDS et/ou par fluorescence de rayons X [2], trois de Palmarola, datées par traces de fission (G. Bigazzi, commun. pers.), dont deux analysées par Particle-Induced X-Ray Emission (PIXE) [20] et 80 de Sardaigne, préalablement analysées par XRF (A.M. de Francesco, commun. pers.) et/ou EMP ([14] et données non encore publiées) et PIXE [15]. La plupart des obsidiennes analysées dans ce travail avaient aussi été caractérisées par d'autres techniques utilisables pour les recherches de provenance, comme la résonance paramagnétique électronique, la spectroscopie Mössbauer et/ou les propriétés magnétiques [7,8,22,23].

La composition élémentaire des échantillons a été déterminée en section polie avec un microscope électronique à balayage JEOL équipé d'un spectromètre par dispersion d'énergie INCAx-sight (Oxford industries). Un faisceau d'électrons accéléré sous une tension de 20 kV balayait une surface d'environ 1 mm2, dix de ces mesures « ponctuelles » étant effectuées par échantillon. Les teneurs en Na, Al, Si, K, Ca et Fe ont été calculées, sur la base de 99% d'oxydes, pour tenir compte d'une teneur maximale en eau de 0,3% et du fait que la somme des teneurs en Ti, Mn (parfois détectés), Mg et P (non détectés) est largement inférieure à 1% dans les obsidiennes [14,25]. La stabilité du système analytique a été contrôlée par le passage répété d'une obsidienne de référence au cours des 18 mois d'accumulation de données. Les coefficients de variation des teneurs élémentaires de cette obsidienne obtenues au cours de cette période sont inférieurs à 3% (Tableau 1).

SEM–EDS analytical data on reference obsidian ARC-URS (see text)

Données analytiques MEB–EDS sur l'obsidienne de référence ARC-URS (voir texte)

| ARC-URS () | Na2O | Al2O3 | SiO2 | K2O | CaO | Fe2O3 |

| ave | 3.08 | 12.52 | 76.04 | 5.30 | 0.61 | 1.45 |

| sd | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| vc | 2.92 | 0.47 | 0.15 | 1.25 | 2.42 | 2.59 |

Résultats

Les résultats sont résumés dans le Tableau 2, où les teneurs élémentaires moyennes par type d'obsidienne sont reportées. Les coefficients de variation sont presque toujours pour Na, Al, Si, K et Ca. Ils atteignent 8% pour les pantellerites, où Ca est proche du seuil de détection. De même, pour Fe, ce coefficient atteint 7% pour Lipari et jusqu'à 10% pour les obsidiennes sardes du type SB2. Le titane n'est qu'occasionnellement dosé dans le matériel de Pantelleria (source de Balata dei Turchi) et les obsidiennes SC de Sardaigne, le manganèse seulement dans les pantellerites.

Element contents determined by SEM–EDS analyses in western Mediterranean obsidians

Teneurs élémentaires déterminées par MEB–EDS dans des obsidiennes de Méditerranée occidentale

| Sources | Na2O | Al2O3 | SiO2 | K2O | CaO | TiO2 | MnO | Fe2O3 | |

| Lipari | ave | 3.66 | 11.95 | 75.84 | 5.12 | 0.72 | nd | nd | 1.70 |

| () | sd | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.01 | – | – | 0.06 |

| Palmarola | ave | 4.22 | 12.18 | 75.26 | 5.02 | 0.47 | nd | nd | 1.85 |

| () | sd | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | – | - | 0.06 |

| Pantelleria | |||||||||

| BDT | ave | 6.19 | 6.88 | 72.63 | 4.27 | <0.31 | <0.35 | <0.42 | 9.03 |

| () | sd | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.04 | – | – | – | 0.17 |

| LDV | ave | 5.57 | 9.90 | 71.11 | 4.79 | <0.39 | 0.54 | <0.40 | 6.96 |

| () | sd | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.01 | – | 0.03 | – | 0.03 |

| Sardinia | |||||||||

| SA | ave | 3.02 | 12.50 | 76.14 | 5.31 | 0.62 | nd | nd | 1.41 |

| () | sd | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.02 | – | – | 0.05 |

| SB1 | ave | 3.05 | 12.84 | 75.27 | 5.55 | 0.77 | nd | nd | 1.52 |

| () | sd | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.03 | – | – | 0.12 |

| SB2 | ave | 2.91 | 12.15 | 76.44 | 5.63 | 0.60 | nd | nd | 1.27 |

| () | sd | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.05 | – | – | 0.12 |

| SC | ave | 2.95 | 13.12 | 74.22 | 5.91 | 0.96 | <0.42 | nd | 1.82 |

| () | sd | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.05 | – | – | 0.13 |

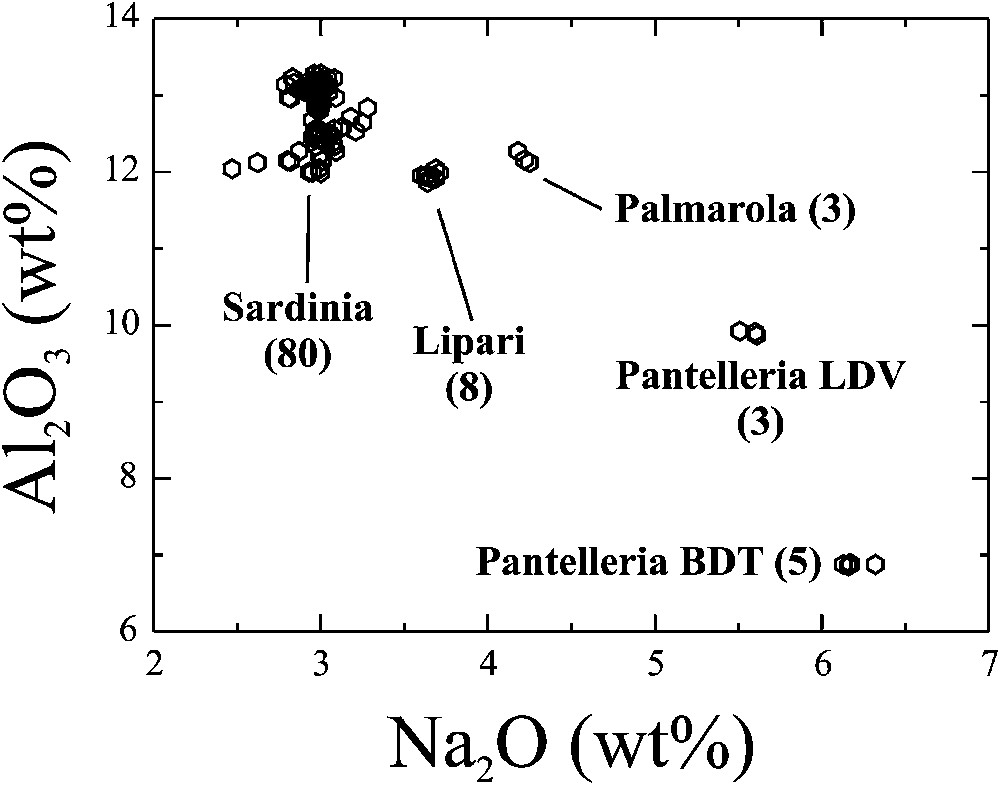

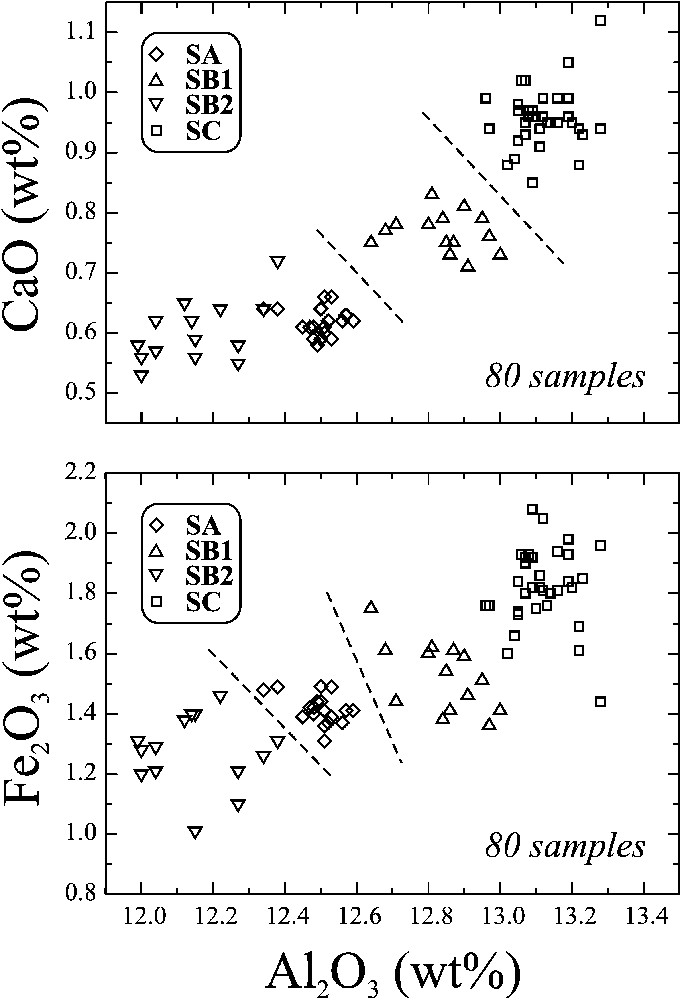

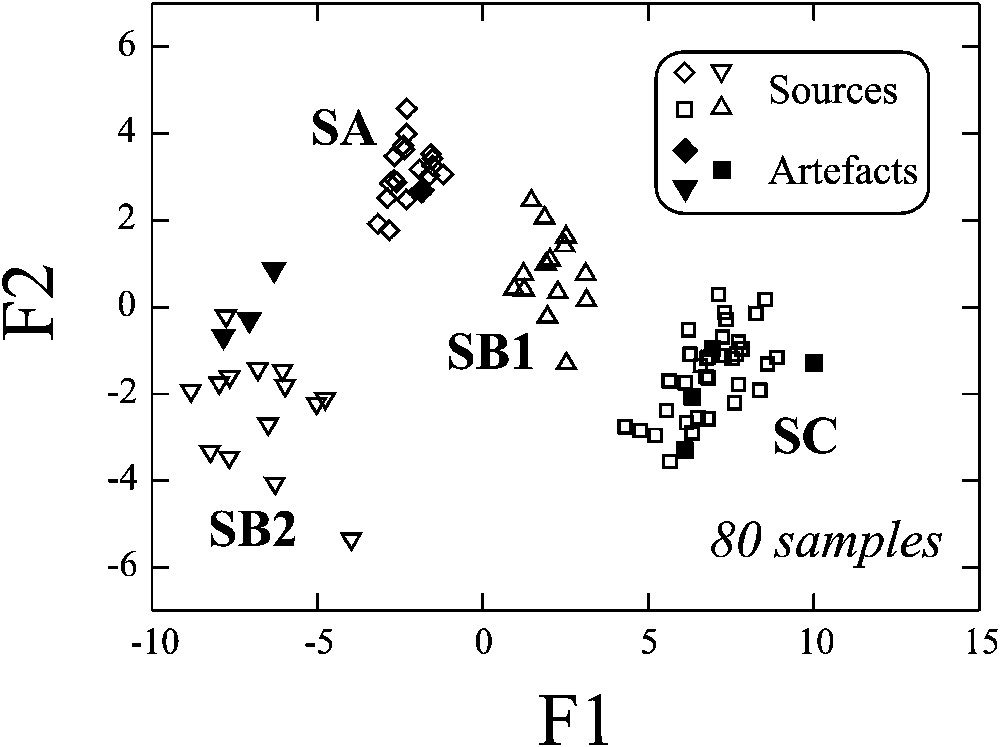

La teneur en Na constitue, à elle seule, un critère de distinction des îles-sources (Tableau 2), comme, dans une moindre mesure, celles en Al (Fig. 2) et Ca. Les quatre types d'obsidiennes sardes peuvent être différenciés les uns des autres par des diagrammes binaires utilisant les teneurs en Al, Ca et Fe (Fig. 3). Toutefois, l'ensemble des éléments dosés participe à ces distinctions. Ainsi, pour la Sardaigne, un diagramme bivarié des deux premières fonctions discriminantes, calculées avec le logiciel XLSTAT (Adinsoft) à partir des six éléments dosés, montre que les quatre types d'obsidiennes du Monte Arci se répartissent selon des champs bien individualisés. Tous les échantillons se trouvent rattachés à un type, avec une probabilité a posteriori toujours supérieure à 99%. À titre de test, nous avons utilisé l'option « prédiction » du logiciel pour traiter huit artefacts en obsidiennes sardes de types précédemment déterminés, traités comme ‘inconnus’. Ils ont été attribués avec succès à leurs types géochimiques (Fig. 4).

Sorting of the western Mediterranean obsidian source-islands from their Na and Al contents.

Distinction entre les îles-sources des obsidiennes de Méditerranée occidentale à partir de leurs teneurs en Na et Al.

Sorting of the Monte Arci (Sardinia) obsidian types from their Al, Ca and Fe contents.

Distinction entre les types d'obsidienne du Monte Arci (Sardaigne) à partir de leurs teneurs en Al, Ca et Fe.

Discriminant analysis of Monte Arci obsidians from element contents as determined by SEM–EDS. SiO2 + 2.385 Fe2O3 – 625.748. CaO + 4.333 Fe2O3 – 1.914.

Distinction des types d'obsidiennes du Monte Arci par analyse discriminante à partir des teneurs élémentaires déterminées par MEB–EDS. F1 = 1,579 Na2O + 14,432 CaO + 9,372 . Al2O3 + 0,229 SiO2 – 12,840 Fe2O3 – 1,914.

Commentaires additionnels et conclusion

Les recherches de provenance des obsidiennes trouvées dans les sites archéologiques requièrent que l'on puisse travailler sur des nombres d'échantillons qui peuvent être très élevés. En Méditerranée occidentale, si l'apparence visuelle est souvent suffisante pour savoir de quelle île provient une obsidienne, il n'en est pas de même pour celles du Monte Arci, en Sardaigne. Il a été montré que l'attribution visuelle à l'un des quatre types d'obsidiennes sardes n'est en accord avec les attributions instrumentales que dans moins de 70% [26,28] à 85% [16] des cas.

De nombreuses méthodes destructives sont capables de discriminer les quatre grands types d'obsidiennes sardes [21,27]. Cependant, certaines d'entre elles sont très consommatrices en temps et/ou en matière, comme la spectroscopie Mössbauer [22] et, dans une moindre mesure, l'activation neutronique [18] ou la caractérisation par les propriétés magnétiques [21]. D'autres approches, comme la spectroscopie infrarouge, sont plus économes en matière, mais demandent encore confirmation de leurs potentialités [13], ou demeurent chères, comme diverses déclinaisons des mesures par ICP. De plus, activation neutronique et spectroscopie infrarouge ne différencient pas les types SB1 et SB2. Parmi les méthodes n'exigeant que quelques milligrammes de matière, la résonance de spin électronique semble promise à un certain futur [7,8,22], et la microsonde électronique utilisant la dispersion de longueur d'onde, dont l'efficacité a été démontrée [14,24], fait déjà l'objet d'un usage courant en Méditerranée occidentale [24]. Ces dernières techniques ne sont cependant pas aussi répandues dans les laboratoires que les microscopes électroniques équipés d'un système d'analyse élémentaire par dispersion d'énergie, qui apparaissent, à l'issue de ce travail, comme une alternative peu destructive, facilement disponible, rapide et peu coûteuse.

La demande de méthodes non destructives pour la caractérisation des matériaux du patrimoine va cependant croissant. Dans le cas des obsidiennes de Méditerranée occidentale, les possibilités de la microspectroscopie Raman ne sont pas encore totalement affirmées [3], et les temps d'acquisition de données semblent encore prohibitifs, sauf peut-être pour des cas d'études très spécifiques. La microminéralogie par MEB n'a pas encore prouvé d'éventuelles possibilités de discriminer les types d'obsidiennes sardes [1,12]. Actuellement, la seule méthode strictement non destructive pour les études de provenance de l'obsidienne employée pour cette région utilise le PIXE [16,20].

Il y a quelque années, Acquafredda et al. [2] avaient observé que les analyses élémentaires menées sur des sections polies ou sur des cassures fraîches d'obsidiennes du Monte Arci par MEB–EDS conduisaient aux mêmes résultats. Des observations de ce type sont actuellement obtenues au laboratoire de Bordeaux sur des obsidiennes anatoliennes, notamment pour des artefacts néolithiques, entre surfaces « archéologiques » et surfaces polies en laboratoire ([6] et données non publiées). Il est donc envisageable que, dans un avenir proche, un couplage MEB–EDS/PIXE puisse traiter, en mode non destructif, tous les problèmes de provenance d'obsidiennes en Méditerranée occidentale, les analyses sous faisceaux d'ions, sous leur déclinaison « faisceau extrait » [5,16] étant réservées aux objets de grandes dimensions ne pouvant entrer dans la chambre d'analyse d'un MEB.

1 Introduction

Obsidian is often present in western Mediterranean Neolithic sites. Fission track analysis (FTA) and geochemical studies have shown that all these obsidians came only from volcanic formations of the Italian islands of Lipari, Palmarola, Pantelleria and Sardinia (Fig. 1). FTA can identify from which island a Neolithic obsidian came from [4]. In each of these islands, obsidian was produced in several instances, and can be found either in ‘primary sources’ as segregations in their rhyolitic mother-rocks or in ‘secondary sources’ as more or less naturally transported blocks to pebbles resulting from the dismantlement of these rocks. Geochemical analyses have shown that from one to nine types of compositions per island could be recognized. A single type was observed for the obsidians of Lipari [9,19], three were recognized in Palmarola [29], and five in Pantelleria, although in this island only two primary sources are known [10].

The situation is more complex in Sardinia. Early determinations by neutron activation analysis (NAA) [11] sorted three types of compositions, SA, SB and SC. Further destructive analyses by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) [17] have shown that the SB type could be subdivided into two discrete subgroups, as confirmed and named SB1 and SB2 by Tykot [24], on the basis of analyses by electron microprobe (EMP) and inductively coupled-mass spectrometry (ICP–MS). It is also possible to further partition from trace element data the SB1 type into three sub-types [25] and the SC type into two sub-types [9] corresponding to as many primary sources. This last refinement is however of no interest in archaeological provenance studies, because obsidians blocks to pebbles of SB1 and of SC sub-types are commonly mixed together in secondary sources of easy access [25].

The Monte Arci obsidians were largely distributed in the northern Tyrrhenian area from the 6th millennium BC and therefore, in provenance studies, having the disposal of a fast, low-cost instrumental method to source Neolithic obsidians from this area is of the utmost importance. In addition, the archaeological demands, especially when chaîne opératoires reconstitutions are involved, imply that one is able to discriminate the four SA, SB1, SB2 and SC types. We show here, to the contrary of an earlier claim [24], that using a scanning electron microscope equipped with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (SEM–EDS), it is possible to discriminate not only the obsidians of the western Mediterranean islands, but also the relevant Monte Arci obsidian types.

2 Sampling

Ninety-nine geological samples of known origin were selected for SEM–EDS analyses, out of which 80 came from the Monte Arci. The elemental compositions of the eight Lipari and of the eight Pantelleria obsidians analysed had previously been determined by MEB–EDS and/or XRF [2]. Of the eight Pantelleria samples, three came from the Balata dei Turchi (BDT) source and five from Lago di Venere (LDV). The three Palmarola obsidians had been dated by FTA (Bigazzi, pers. commun.) and two of them analysed by Particle-Induced X-Ray Emission (PIXE) [20]. Major and trace element contents of six obsidians from Sardinia, representative of the four types, had been determined by destructive XRF (A.M. de Francesco, pers. commun.) and by PIXE [15]. All these obsidians were also characterized by electron-spin resonance (ESR) and most of all by Mössbauer spectroscopy and by their magnetic properties, three techniques shown to be alternative approaches to western Mediterranean obsidian sourcing [7,8,22,23].

Another 74 samples from primary and secondary sources of the Monte Arci were sampled by us. The content of elements Na, Mg, Al, Si, P, K, Na, Ca, Ti, Mn, Fe and Ba of all the Monte Arci samples treated in this work had been determined by EMP–WDS ([14] and unpublished data) prior to SEM–EDS measurements, from the same polished sections (see below).

3 Experimental procedures

Slices of about 1 cm2 were cut from each sample and included in an araldite resin. About six to eleven samples were mounted together in 40-mm-diameter wafers and were given an electron-microprobe high-quality polishing. After the last polishing step (0.1-micron grain-sized polycrystalline diamond slurry) the samples were ultrasonically washed in bi-distilled water, in ethanol and were carbon-coated. The elemental compositions were realized at Bordeaux with a JEOL JMS 6460 LV scanning electron microscope operating at an 20 kV accelerating voltage. For each measurement, the electron beam diameter swept a surface of about . Ten such measurements per sample were taken in various points. The fluorescence X-rays emitted by the samples were collected by an Oxford Industries INCAx-sight energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS) with a 133-eV resolution at 5.9 keV. All spectra were obtained with the same (150 000) total number of counts, corresponding to acquisition times of about 70 s. The data treatment software uses a Phi-Rho-Z approach to calculate element contents as percent oxides. Only Na, Al, Si, K, Ca and Fe contents could be obtained for all samples. Elements Mg and P are always below detection level and Ti and Mn rarely above. The total oxide content of the latter four elements in obsidians is well below 1% (see, e.g., [14,25]). Thus, taking also into account a maximum water content of 0.3%, the total oxides composition of our samples was normalized to 99%. The oxide per cent elemental composition calculated for each sample is averaged over the ten ‘point’ measurements realized. Only in five cases (0.5% of the spectra) had an ‘anomalous’ spectrum to be rejected, most probably due to the presence of a crystalline phase in the volume analysed.

The overall stability of the analytical system was controlled by repeated analyses of sample ARC-URS, a type SA Sardinian obsidian. During the 18-month period of data accumulation, the ARC-URS composition was determined six times from the same polished section, each time after one re-polishing to obtain a new clean surface. Variations in element contents were found to be around the average (Table 1).

4 Results

Ninety-nine obsidians were measured. The results are summarized in Table 2. All obsidian groups show a remarkable homogeneity. Elements Na, Al, Si, K and Ca present nearly always a variation coefficient from sample to sample within a group. Exceptions correspond to the Sardinian SB2 type, with 6% for Na and 8% for Ca and for the Pantellerites, where Ca is only barely detectable. As for the ARC-URS internal standard, Fe is among the elements that present the highest content dispersion. Its variation around the average is still for Lipari, Palmarola, Pantelleria and SA obsidians, but it reaches 7% for the SB1 and SC types and up to 10% for SB2 obsidians. Titanium was detected only in some ‘point’ measurements in Pantelleria BDT and Sardinia SC obsidians. Its content could be determined in all point measurements only in Pantelleria LDV samples. Manganese was detected only in Pantelleria samples.

The distinction between obsidians from different islands is clear-cut from their single Na content and in a lesser way by their Al contents. In a binary NaAl contents diagram (Fig. 2), the Lipari obsidians are intercalated between Palmarola and Sardinia obsidians. However they are easily separated from the former by their Ca content. They can also be sorted from Sardinian obsidians from their lower Al and Ca than the SB1 and SC types respectively, and from their higher Fe than the SA and SB2 types. The Pantelleria peralkaline obsidians composition differ from that of the other islands by nearly all their elements contents, which singles them in first place. Moreover, the BDT and LDV Pantelleria obsidian sources can be differentiated from each other by their Na, Al, Si, K, and Fe contents.

The four Sardinian types can be fingerprinted from each other by binary diagrams based on, e.g., their Al, Ca and Fe contents (Fig. 3). However, the other elements (apart from Ti and Mn) participate to the individualisation of each type, as shown by a multivariate analysis. A bivariate plot of the first two discriminant functions determined with the XLSTAT software (Adinsoft) shows four well-defined groups of points corresponding to the SA, SB1, SB2 and SC obsidian types (Fig. 4). All geological samples were attributed their correct type (as previously determined, see Section 2 above), with a posterior probability always exceeding 99%. As a test, the prediction option in XLSTAT was used for eight artefacts of known Sardinian obsidian types, treated as ‘unknowns’. These samples were prepared in the same way as source samples, but from millimetre-sized fragments. They were rightly attributed to the SA, SB2 and SC types, respectively.

5 Final comments and conclusion

Sourcing the obsidians found in archaeological sites requires that samples can be characterized by the hundreds, if not by the thousands. Visual appearance can in general fulfil this goal in the western Mediterranean when only the source-island of any ‘archaeological’ obsidian is looked for. However this approach is not efficient enough for the distinction of the Sardinian obsidian types. Due to facies convergences, or to the small size of some artefacts, the visual attribution of any obsidian to one of the four relevant Monte Arci obsidian types is successful only to less than 70% [26,28] to 85% [16] of the cases.

Many partly destructive methods have proven their capabilities in Monte Arci obsidian types' sorting [21,27]. However, some of them are time- and/or matter-consuming, as Mössbauer spectroscopy [22] and in a lesser way, neutron activation analysis (NAA) [18] and magnetic properties studies [21]. Others are not yet firmly established, as infrared spectroscopy (IRS) [13], or are expensive, as the various declinations of the ICP techniques. Moreover, NAA and IRS do not discriminate the SB1 from the SB2 Monte Arci obsidian types. Among the approaches requiring no more than a millimetre-sized sampling on an obsidian artefact, electron-spin resonance seems to have a bright future [7,8,22], and only EMP operating with a wavelength-dispersion spectrometer proved its efficacy [14,24] and received a wide application in the western Mediterranean area [24]. SEMs equipped with an energy dispersion system of elemental composition analysis are by far more frequent than EMPs. We showed here that this low-cost, fast-operating technique does offer an alternative to EMP, with the only determination of six major element contents.

The demands of strictly non-destructive methods for the characterization of materials from the cultural heritage are in constant progression. In the case of western Mediterranean obsidian sourcing, the potentialities of microRaman spectroscopy are not yet fully established and the data acquisition times needed might anyway limit the use of this technique to very specific cases [3]. SEM mineralogical determinations have not yet proven their ability to discriminate the four Monte Arci types of obsidians [1,12]. To date, the only strictly way of non-destructive sourcing used in this region of the world is by ion-beam analysis [16,20]. Several years ago, Acquafredda et al. [2] observed that the elemental analysis of Monte Arci obsidians by SEM–EDS from polished sections or from fresh fractures gave undistinguishable results. Similar data were obtained in our laboratory for Anatolian source samples and artefacts and they are currently used in provenance studies ([6] and yet unpublished data). Thus one may expect than in a near future the coupling of SEM–EDS for ‘small’ archaeological pieces with PIXE in its extracted beam version for the larger ones (see [5,16]) will allow one to treat any obsidian sourcing question also in the western Mediterranean area.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Floréal Daniel for his efficient management of the CRP2A scanning electron microscope maintenance. They also thank the colleagues who provided them with obsidian samples, Pasquale Acquafredda (Bari), Giulio Bigazzi (Pisa) and Anna Maria de Francesco (Arcavacata di Rende).