Abridged English version

Introduction

The main morphotectonic units that form the Scottish Highlands did probably already exist during Late Palaeozoic times [13]. The magnitude of vertical movements that affected the area after the Late Palaeozoic is still largely debated [6,13,16,44]. Most of the post-Devonian series have been eroded, being only preserved in the offshore basins and in the Midland Valley (Fig. 1a) [20,32]. Several post-Devonian tectonic phases have occurred, but related vertical movements are difficult to quantify [35,39,42,45]. Low-temperature geochronology studies from the literature [6,16,17,44] consider that the Highlands region has behaved as a single block, with no possibility of differential movements along large lithospheric faults. In this study, we decipher and quantify the various exhumation events that affected the area of the Great Glen Fault (GGF) Valley, in order to detect any potential differential movements across the GGF itself.

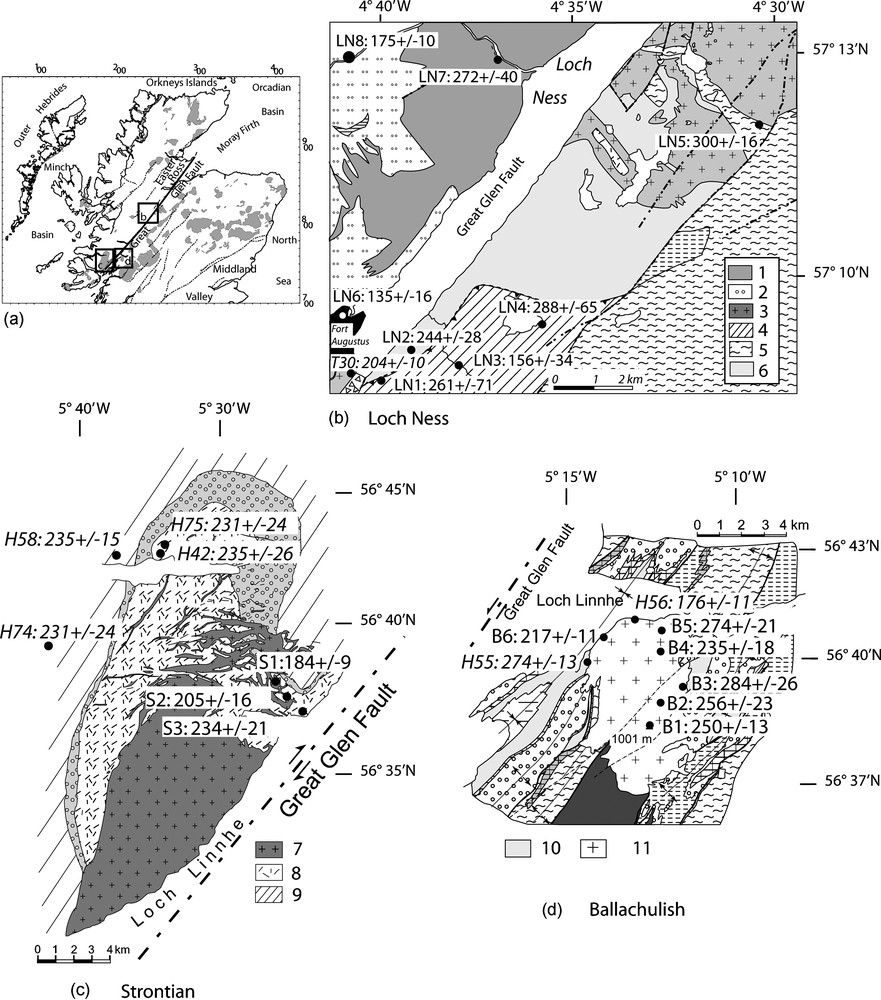

(a) Carte générale de l’Écosse, montrant les principales failles, ainsi que la répartition des granites calédoniens (en gris). Les cadres correspondent aux zones d’étude. (b)–(d) Cartes géologiques détaillées du loch Ness, de Strontian et du Ballachulish, avec la position et les âges centraux traces de fission (en Ma) des échantillons analysés. Sont également reportés les âges traces de fission disponibles dans la littérature (H42, H,55, H56, H58, H74, et H75 sont issus de [18] ; T30 de [46]). Les cartes sont issues des feuilles 52E, 53, 73W et 73E du British Geological Survey. Seules les formations échantillonnées sont reportées en légende. 1. Achnaconeran Striped Fm. (pélites). 2. Up. Garry Fm. (psammites). 3. Granitoïdes. 4. Tarff Banded Fm. (schistes). 5. Glen Doe Fm. (psammites). 6. Glen Buck Pebbly Psammite Fm. 7. Granite à biotite. 8. Granodiorite. 9. Séries métamorphiques de Moine. 10. Phyllites d’Appin. 11. Granites du Ballachulish. Masquer

(a) Carte générale de l’Écosse, montrant les principales failles, ainsi que la répartition des granites calédoniens (en gris). Les cadres correspondent aux zones d’étude. (b)–(d) Cartes géologiques détaillées du loch Ness, de Strontian et du Ballachulish, avec la position et ... Lire la suite

Fig. 1. (a) General map of Scotland showing the main faults and the Caledonian granites (in grey). Boxes correspond to the study areas. (b)–(d) Detailed geological maps of the Loch Ness, the Strontian and the Ballachulish, with the position and age of the samples used in this work. Also reported are data from the literature (H42, H55, H56, H58, H74, and H75 are from [18]. T30 is from [46]). Maps are modified from sheets 52E, 53, 73W and 73E of the British Geological Survey. Only the formations sampled for this study are presented in the key. 1. Achnaconeran Striped Fm. (pelites). 2. Up. Garry Fm. (psammites). 3. Granitoids. 4. Tarff Banded Fm. (schists). 5. Glen Doe Fm. (psammites). 6. Glen Buck Pebbly Psammite Fm. 7. Biotite-bearing granite. 8. Granodiorite. 9. Moine metamorphic series. 10. Appin phyllites. 11. Ballachulish granites. Masquer

Fig. 1. (a) General map of Scotland showing the main faults and the Caledonian granites (in grey). Boxes correspond to the study areas. (b)–(d) Detailed geological maps of the Loch Ness, the Strontian and the Ballachulish, with the position and ... Lire la suite

The GGF is a major, subvertical, reactivated fault system that cuts across the Caledonian orogenic belt of Scotland [27] (Fig. 1). Movements along the fault have a history that extends at least into the Early Palaeozoic [1,21,41]. The fault, which participated in the genesis and emplacement of some of the Late Caledonian Granites (435 to 390 Ma) [23,30,40,46] was initiated in the Late Caledonian orogenic stage, during the oblique continental convergence following the closure of the Iapetus Ocean [1,21,41]. Middle Silurian to Early Devonian (ca. 428 to 390 Ma) large strike-slip movements have been documented. While the current consensus is that sinistral translation has been dominant [14,21,22,36,41,43,46], dextral motion has also been proposed [21,35]. A second period of movement occurred between the Latest Frasnian and the Early Permian [35]. During that period, dextral slip was associated with basin inversion within the Orkney area [39]. Finally, Underhill and Brodie [45] documented a post-Early Cretaceous limited strike-slip motion, associated with basin inversion within the Easter Ross and the Inner Moray Firth.

Two vertical profiles from the Strontian and Ballachulish plutons situated on either side of the GGF were sampled (Fig. 1c and d, Table 1). Additionally, a roughly horizontal profile, the Loch Ness profile (minimizing the variations in altitude between samples to allow a better comparison) across the GGF corridor near Fort Augustus (Fig. 1b) was also sampled, integrating some of the secondary faults parallel to the main GGF in that area.

Données traces de fission

Table 1 Fission track data

| Localité | Echantillon | Altitude [m] | N | ρstd × 104 cm−2 | ρs × 104 cm−2 | ρi × 104 cm−2 | U [ppm] | P(χ2) [%] | Var [%] | MTL [μm] (±1 σ) | D std | Dpar (μm) | Age central (±2 σ) [Ma] |

| Ballachulish | B6 | 20 | 20 | 188.9 (8680) | 324.4 (1064) | 299.1 (981) | 24 | 22 | 12 | 11.79 ± 0.18 (100) | 1.80 | 2.19 (420) | 217 ± 11 |

| B5 | 100 | 20 | 136.8 (8424) | 566.4 (1954) | 409.6 (1413) | 36 | 37 | 25 | 12.68 ± 0.14 (100) | 1.63 | 2.20 (418) | 274 ± 21 | |

| B4 | 240 | 19 | 129.7 (8424) | 262.2 (3396) | 210.3 (2724) | 20 | 11 | 7 | 12.06 ± 0.17 (100) | 1.68 | 1.72 (419) | 235 ± 18 | |

| B3 | 610 | 20 | 122.6 (8424) | 320.3 (1970) | 206.2 (1268) | 21 | 94 | 1 | 12.32 ± 0.16 (100) | 1.61 | 1.80 (419) | 284 ± 26 | |

| B2 | 910 | 18 | 147.5 (8424) | 272.3 (697) | 227.7 (583) | 21 | 87 | 8 | 12.64 ± 0.16 (100) | 1.54 | 1.69 (420) | 256 ± 23 | |

| B1 | 1001 | 20 | 182.8 (8680) | 202.7 (1753) | 162.5 (1406) | 13 | 1 | 8 | 12.34 ± 0.18 (100) | 1.77 | 1.76 (420) | 250 ± 13 | |

| Strontian | S3 | 15 | 19 | 151.1 (8424) | 152.6 (479) | 143.6 (451) | 12 | 97 | 6 | 10.76 ± 0.16 (100) | 1.59 | 1.55 (419) | 234 ± 21 |

| S2 | 465 | 17 | 155.2 (8680) | 124.7 (394) | 101.0 (319) | 10 | 60 | 7 | 11.76 ± 0.18 (103) | 1.44 | 1.58 (408) | 205 ± 16 | |

| S1 | 654 | 23 | 161.3 (8680) | 136.4 (839) | 127.6 (785) | 11 | 51 | 4 | 11.85 ± 0.13 (100) | 1.25 | 1.55 (420) | 184 ± 9 | |

| loch Ness | LN1 | 90 | 16 | 119.7 (5327) | 160 (36) | 106.7 (24) | 1 | 100 | 0 | 11.9 ± 0.16 (70) | 1.62 | 1.80 (400) | 261 ± 71 |

| LN2 | 190 | 22 | 201.8 (9089) | 864.6 (166) | 760.4 (146) | 7 | 90 | 1 | 11.8 ± 0.2 (100) | 1.96 | 1.74 (410) | 244 ± 28 | |

| LN3 | 180 | 16 | 120 (6837) | 114.1 (46) | 96.8 (39) | 1 | 100 | 0 | 12.0 ± 0.19 (80) | 1.86 | 1.68 (417) | 156 ± 34 | |

| LN4 | 300 | 19 | 125.6 (6837) | 168.5 (61) | 80.1 (29) | 1 | 100 | 1 | 12.7 ± 0.13 (34) | 1.25 | 1.64 (380) | 288 ± 65 | |

| LN5 | 200 | 20 | 170.5 (8680) | 518.42 (3489) | 315.9 (2126) | 27 | <1 | 31 | 12.3 ± 0.15 (103) | 1.52 | 1.72 (420) | 300 ± 16 | |

| LN6 | 20 | 13 | 128.4 (6837) | 613.7 (143) | 643.8 (150) | 8 | 96 | 2 | 11.5 ± 0.18 (101) | 1.80 | 1.69 (419) | 135 ± 16 | |

| LN7 | 40 | 30 | 177.8 (9089) | 106.8 (111) | 74.1 (77) | 1 | 90 | 1 | 12.6 ± 0.14 (54) | 1.37 | 1.68 (400) | 272 ± 40 | |

| LN8 | 60 | 20 | 139.5 (6837) | 1111.9 (646) | 974.2 (566) | 10 | 86 | 1 | 12.3 ± 0.16 (100) | 1.55 | 1.73 (420) | 175 ± 10 |

Fission-track analysis results

Apatite samples were prepared for AFT analysis following the standard method [18]. Mean ages were obtained using the zeta calibration method [19] (Table 1). Detailed laboratory conditions are given in Table 1. CN5 glass was used as dosimeter with a zeta value of 297 ± 17, obtained on both Durango and Mont Dromedary apatite standards. Spontaneous fission tracks were etched using 6.5 % HNO3 for 45 s at 20 °C. Induced fission tracks were etched using 40 % HF for 40 min at 20 °C. Fission tracks were counted and measured on a Zeiss microscope, using a magnification of 1250 under dry objectives. All ages, calculated using the Trackkey software (Dunkl, University of Tubingen, Germany) are central ages, and errors are quoted at ±2 σ (Table 1). The AFTSolve® software [29] was used to model the thermal histories, using the Ketcham et al. [28] annealing model and the Dpar parameter (mean width of the fission tracks in a given grain, indicating the relative Cl and F contents in the apatite) [5,34].

Loch Ness profile (Fig. 1b)

The eight samples of Precambrian (Moine and Grampian Groups) schists and gneisses [3,4] can be separated into two groups:

- • five ‘old’ samples with central ages between 244 ± 28 Ma and 300 ± 16 Ma, with mean track lengths from 11.8 ± 0.2 μm to 12.7 ± 0.13 μm;

- • three ‘young’ samples with central ages between 135 ± 16 Ma and 175 ± 10 Ma, with mean track lengths from 11.5 ± 0.18 μm to 12.3 ± 0.16 μm.

Samples from each group are found on both sides of the fault. The Dpar parameter does not show any large chemical difference between the samples (Table 1). Fig. 2 shows that there is no difference within the distribution of the central ages from the Loch Ness samples on either side of the GGF.

Âges centraux traces de fission des échantillons du loch Ness en fonction de la distance à la Great Glen Fault. Losanges noirs : cette étude ; carrés : [46] ; triangle : [17]. La ligne pointillée indique la position de la faille.

Fig. 2. Central FT age from the Loch Ness samples plotted against the sampling distance to Great Glen Fault. Black diamonds are samples from this study, open squares are samples from [46], and the open triangle is from [17]. The heavy line indicates the position of the GGF.

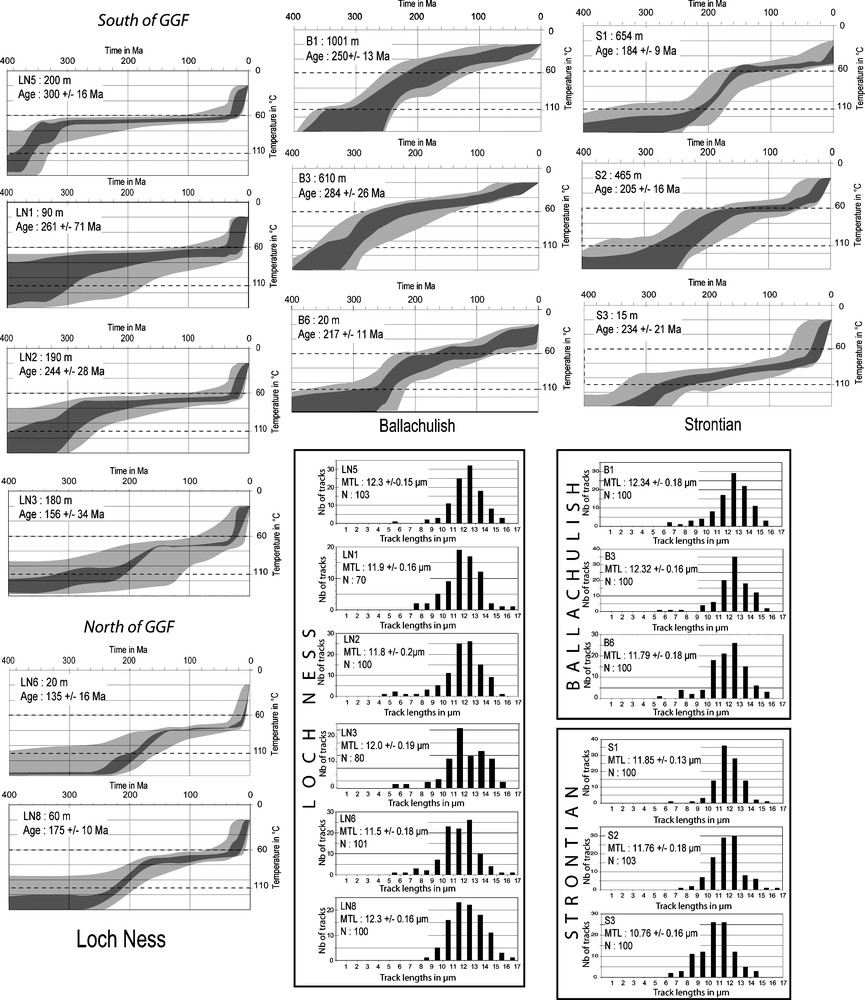

In thermal models (Fig. 3), the ‘old’ samples cross the 110 °C isotherm between 400 and 300 Ma (time when the samples cross a given isotherm are read from the dark-grey 1 σ zone of error), then stay within the upper part of the Partial Annealing Zone (PAZ) until 40 to 25 Ma, when they seem to cool again to surface temperature. The ‘young’ samples cross the 110 °C isotherm between 225 and 175 Ma to reach 70 to 80 °C around 170 Ma. They are all affected by a last cooling event starting between 40 and 20 Ma.

Histoires thermiques de certains échantillons du loch Ness, du Ballachulish et du Strontian, obtenues par modélisation numérique des longueurs de traces (logiciel AFTSolve). Les trois histoires thermiques sélectionnées dans chaque zone d’étude sont représentatives de l’ensemble des échantillons. La zone en gris foncé représente les courbes à moins d’1 σ d’erreur par rapport à la meilleure courbe, la zone gris clair représente les courbes à 2 σ d’erreur. Seule la zone entre 110 °C et 60 °C doit être considérée. Les histogrammes de répartition des longueurs de traces sont donnés pour les modélisations présentées. Masquer

Histoires thermiques de certains échantillons du loch Ness, du Ballachulish et du Strontian, obtenues par modélisation numérique des longueurs de traces (logiciel AFTSolve). Les trois histoires thermiques sélectionnées dans chaque zone d’étude sont représentatives de l’ensemble des échantillons. La zone ... Lire la suite

Fig. 3. Cooling histories of some of the Loch Ness, Ballachulish and Strontian samples obtained from apatite fission tracks length modelling using the AFTSolve software [31]. The three thermal histories selected in each zone are representative of all the samples in that zone. The dark-grey area represents the envelope of all the possible temperature–time curves falling within a 1 σ error interval from the best-fit curve. The light-grey area represents the envelope of all the cooling curves falling within a 2 σ interval. Only the area between 110 and 60 °C is meaningful for the cooling path. Track-length histograms are given for the modelling presented. Masquer

Fig. 3. Cooling histories of some of the Loch Ness, Ballachulish and Strontian samples obtained from apatite fission tracks length modelling using the AFTSolve software [31]. The three thermal histories selected in each zone are representative of all the ... Lire la suite

Ballachulish and Strontian profiles (Fig. 1c and d)

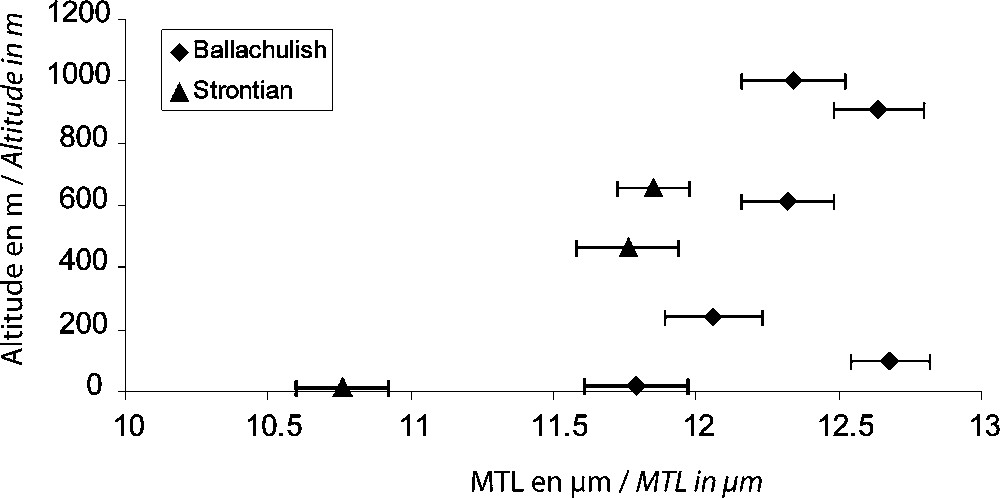

Central ages from the six Ballachulish granite samples (Fig. 1d), south of the GGF, vary between 217 ± 11 Ma and 284 ± 26 Ma, with mean track lengths from 11.79 ± 0.18 μm to 12.68 ± 0.14 μm (Table 1). There is no obvious relationship between age and altitude, but the mean track length generally increases with altitude (Fig. 4). Samples cross the 110 °C isotherm between 325 and 245 Ma and the 60 °C isotherm between 250 and 150 Ma (Fig. 3), without any indication on the post-Jurassic thermal history.

Diagramme longueur moyenne des traces (MTL) versus altitude pour les échantillons du Strontian et du Ballachulish étudiés ici.

Fig. 4. Mean track length (MTL) versus altitude plot for the Strontian and Ballachulish samples studied here.

Central ages from Strontian granite samples (Fig. 1c), north of the GGF, vary from 184 ± 9 Ma to 234 ± 31 Ma, with mean track lengths from 10.76 ± 0.16 μm to 11.85 ± 0.13 μm (Table 1). Samples again show very slow cooling after crossing the 110 °C isotherm between 280 and 200 Ma (Fig. 3). The highest samples reached the upper PAZ around 170 ± 10 Ma, but sample S3 only reaches the 60 °C isotherm around 40 to 20 Ma after a late cooling event.

Discussion

Palaeozoic history

The results of this study are consistent with previously published data [6,16,44], especially concerning the Palaeozoic–Mesozoic history. The Palaeozoic exhumation of the ‘old’ Loch Ness samples seems to occur before that of both Ballachulish and Strontian samples. The Permo-Triassic event affecting the ‘young’ samples is similar to the first cooling episode in the Strontian. The difference in thermal history between Strontian and Ballachulish samples can be related to vertical movements across the GGF during Late Carboniferous–Early Permian. Those movements could have exhumed the Ballachulish area, whereas the Strontian one remained at depth. Rogers et al. [35] indicate that between 15 and 20 km of horizontal motion occurred along the GGF between Late Frasnian and Early Permian, contemporaneously with a compression in the Orcadian basin [10,35,39]. Evidence for Permo-Carboniferous compression, probably linked to the Hercynian orogeny, has also been reported [8,11,39,45].

Nonetheless, the intercalation of ‘young’ ages in the Loch Ness profile could be due to the distribution of the vertical movements on several second-order faults in that area. This remains to be tested, but it would suggest that the distribution of the deformation could vary alongside the GGF corridor.

Mesozoic history

After the important Late Palaeozoic–Triassic cooling, samples were slowly exhumed. Assuming that there was no local tilting of the Strontian complex after cooling started [26], a rough calculation of a mean Mesozoic (from ca. 160 to ca. 40 Ma) geothermal gradient of 46 °C km−1 can be obtained from thermal modelling. High palaeogeothermal gradients have already been reported from the Carboniferous of the Inner Moray Firth or the Jurassic–Cretaceous series of northern England [12,15]. This geothermal gradient implies a maximum denudation of 2 km between 160 and 40 Ma, less than the 3 km previously calculated [6,31,44]. This conclusion is consistent with the idea of Hall [13], suggesting that the main topographical characteristics of the Highlands were already established in the Late Palaeozoic. It implies only low denudation in Mesozoic and Cenozoic periods.

Tertiary history

Only the Loch Ness and Strontian samples record the Tertiary history. A strong increase in cooling rate is observed from 40 to 25 Ma, especially in the ‘young’ Loch Ness samples. This cooling event can be linked either to tectonic activity or to the relaxation of the high Mesozoic geothermal gradient. The present geothermal gradient is 35 °C km−1 [38], by 11 °C lower than the one postulated for the Mesozoic. Thermal relaxation could thus explain about 20 % of the Tertiary cooling. Two Palaeogene and Neogene uplift episodes have been described in the region of the northeastern Atlantic [24,25,33]. The Palaeogene episode is linked to the Iceland plume, whereas the Neogene event, associated with basin subsidence, is more difficult to explain [2,7,9,25,37]. As these two events appear as a single one in our thermal models, we have to consider a single cooling episode during the Tertiary. Considering a 35 C km−1 geothermal gradient, an initial temperature of 70 °C and the 20 % due to relaxation, 1.6 km of section could have been eroded since about 40 Ma, slightly less than the 3 km calculated in previous studies [6,44].

Conclusion

Apatite fission-track analyses reveal three main uplift/denudation episodes in the Scottish Highlands. (a) In the Late Palaeozoic, differential vertical movements across the GGF led to the exhumation of the Ballachulish area south of the fault, to a temperature of less than 60 °C, while the Strontian area, north of the fault, remains at depth. However, these movements seem to have been locally distributed on several secondary faults inside the GGF corridor, north and south of the main fault. This partitioning, observed in the Loch Ness area, may affect other localities along the GGF corridor. The Grampian and North Highland blocks may have thus behaved independently during Late Palaeozoic times. (b) The high Mesozoic geothermal gradient calculated from fission tracks analysis in the Strontian area implies a maximum of 2 km of denudation between the Late Jurassic and the Early Eocene (160 and 40 Ma). (c) From Late Eocene–Oligocene times (40–25 Ma), samples were affected by a general uplift implying between 1.6 and 2 km of erosion, slightly less than the 3 km calculated by previous studies [6,31,44].

1 Introduction

Les unités morphotectoniques principales qui forment les Highlands d’Écosse étaient probablement déjà constituées au Paléozoïque supérieur [13]. Toutefois, l’ampleur des mouvements verticaux post-paléozoïques est toujours débattue [6,13,16,44]. La majeure partie des séries sédimentaires post-dévoniennes ont été érodées et ne sont plus observables que dans les bassins, tels le Inner Moray Firth, le bassin des Orcades, le bassin de Minch et la Middland Valley (Fig. 1a), où il a été démontré qu’une partie des sédiments post-dévoniens dérivent de l’érosion des Highlands du Nord [20,32]. Toutefois, ces différentes phases de déformation ont induit des mouvements verticaux de faible amplitude, difficiles à quantifier [35,39,42,45]. Les travaux de géochronologie à basse température disponibles [6,16,17,44] considèrent que l’ensemble de la région des Highlands se comporte comme un bloc unique, sans possibilité de mouvements différentiels de part et d’autre des grandes failles décrochantes qui affectent le socle. L’objectif de cette étude est, d’une part, de mettre en évidence et de quantifier les principaux épisodes de refroidissement (et donc d’érosion des reliefs) ayant affecté la zone proche du corridor du loch Ness et, d’autre part, de détecter d’éventuels mouvements différentiels entre les blocs Nord Highlands et Grampian, situés respectivement au nord et au sud de la Great Glen Fault (GGF).

Le système de la GGF est un couloir de déformation majeur, subvertical, plusieurs fois réactivé, affectant la chaîne Calédonienne d’Écosse [27] (Fig. 1). Les mouvements le long de cette faille débutent probablement lors du dernier stade de l’orogenèse calédonienne (Paléozoïque inférieur), durant l’épisode de convergence oblique qui suit la fermeture de l’océan Iapetus [1,21,41]. Au cours de cette période, la GGF participe à la genèse et à la mise en place de certains des granites tardi-calédoniens (435–390 Ma) qui la jalonnent [23,30,40,46]. Des jeux décrochants importants sont enregistrés au Silurien moyen–Dévonien inférieur (ca. 428–390 Ma). Ces mouvements semblent majoritairement sénestres [14,21,22,36,41,43,46], bien que certains auteurs proposent également des mouvements dextres [21,35]. La GGF a ensuite été réactivée par des décrochements dextres entre le Frasnien supérieur et le Permien inférieur, en association avec l’inversion de bassins sédimentaires dans la zone des Orcades [35,39]. Enfin, des mouvements décrochants de plus faible amplitude sont enregistrés après le Crétacé inférieur, associés à des inversions de bassins sédimentaires dans l’Easter Ross et le Moray Firth (Fig. 1).

Pour cette étude, deux profils verticaux ont été échantillonnés dans les plutons granitiques calédoniens de Strontian et du Ballachulish, situés de part et d’autre de la GGF (Fig. 1c et d). Un profil subhorizontal (le profil du loch Ness), minimisant les différences d’altitude entre les échantillons pour permettre une meilleure comparaison des résultats, a également été échantillonné plus à l’est, de part et d’autre du corridor de la GGF, incluant certaines des failles cartographiées parallèles à la GGF (Fig. 1b).

2 Résultats des analyses des traces de fission

Les âges traces de fission ont été obtenus suivant la méthode standard [18], en utilisant la calibration zêta [19]. Le verre CN5 a été utilisé comme dosimètre, avec une valeur de zêta de 297 ± 17, obtenue sur les standards d’apatites de Durango et de Mount Dromedary. Les traces spontanées ont été révélées par une attaque par HNO3 à 6,5 % pendant 45 s à 20 °C. Les traces induites ont été révélées par une attaque par HF à 40 % pendant 40 min à 20 °C. Les traces de fission ont été comptées à l’aide d’un microscope Zeiss Axioplan II, sous un grossissement de 1250×. Tous les âges sont des âges centraux, avec une erreur à 2 σ.

Le logiciel AFTSolve® [29] a permis de modéliser les histoires thermiques à partir du modèle cinétique de Ketcham et al. [28], en utilisant le paramètre Dpar (diamètre moyen des traces de fission dans chaque cristal d’apatite, qui traduit la concentration en Cl et en F des cristaux étudiés) [5,34], calculé pour chaque échantillon.

3 Profil horizontal du loch Ness

Huit échantillons de schistes et de gneiss précambriens (Moine et Grampian Group [3,4]) ont été prélevés sur un profil NW–SE à travers la zone de faille de la GGF (Fig. 1b). Les différences d’altitude entre les échantillons ont été minimisées (de 20 à 300 m), pour pouvoir comparer directement les histoires thermiques.

Les échantillons peuvent être séparés en deux groupes :

- • cinq « vieux » échantillons (LN1, LN2, LN4, LN5 et LN7), présents de part et d’autre de la faille, dont les âges centraux varient entre 244 ± 28 Ma et 300 ± 16 Ma pour des longueurs moyennes de traces de fission comprises entre 11,8 ± 0,2 μm et 12,7 ± 0,13 μm ;

- • trois « jeunes » échantillons (LN3, LN6 et LN8), intercalés entre les premiers, dont les âges centraux varient entre 135 ± 16 Ma et 175 ± 10 Ma, pour des longueurs moyennes de traces de 11,5 ± 0,18 μm à 12,3 ± 0,16 μm.

Le paramètre Dpar [5,34] ne montre aucune différence chimique majeure entre les échantillons. Les variations d’âge sont donc liées à des différences d’histoire thermique. (Tableau 1)

La Fig. 2 montre l’ensemble des âges centraux des échantillons du loch Ness, ainsi que des données de la littérature, projetés sur une ligne perpendiculaire à la GGF. Il n’y a pas de différence majeure entre les deux côtés de la faille, seuls les âges « jeunes » introduisent des variations locales du profil.

Les modélisations de l’histoire thermique des échantillons montrent également une différence entre les deux groupes d’âges (Fig. 3). Les « vieux » échantillons passent l’isotherme 110 °C entre 400 et 300 Ma (les gammes d’âge de passage d’un isotherme sont lues en considérant les deux extrêmes de l’enveloppe gris foncé ( ± 1 σ) des graphiques), puis restent dans la partie supérieure de la zone partielle d’effacement des traces (ZPE), jusque vers au moins 40 à 25 Ma. À cette époque, il semblerait que le refroidissement reprenne jusqu’à atteindre la température de surface. Les « jeunes » échantillons passent l’isotherme 110 °C entre 250 et 175 Ma environ et atteignent 70 à 80 °C vers 170 Ma. Une dernière phase de refroidissement, plus marquée que dans le premier groupe d’échantillons, car son initiation se fait à des températures plus hautes, débute entre 40 et 20 Ma.

4 Profils verticaux du Ballachulish et de Strontian

Six échantillons de granite ont été prélevés sur le Ballachulish, au sud de la GGF (20 à 1001 m d’altitude) et trois échantillons de granite et granodiorite sur le Strontian, au nord de la GGF (15 à 654 m d’altitude) (Fig. 1c et d).

Les âges obtenus sur le Ballachulish varient entre 217 ± 11 Ma et 284 ± 26 Ma, pour des longueurs moyennes de traces de 11,79 ± 0,18 à 12,68 ± 0,14 μm. Du fait des marges d’erreur importantes, il n’y a pas de corrélation âge–altitude évidente. En revanche, la longueur moyenne des traces augmente de manière générale avec l’altitude (Fig. 4).

Les modélisations de l’histoire thermique des échantillons montrent un passage à l’isotherme 110 °C entre 300 et 245 Ma et de l’isotherme 60 °C entre 250 et 150 Ma (Fig. 3). Les traces de fission sur apatite dans le Ballachulish n’enregistrent donc pas l’histoire thermique post-jurassique.

Les âges obtenus sur Strontian varient entre 184 ± 9 et 234 ± 21 Ma, pour des longueurs moyennes de traces de 10,76 ± 0,16 à 11,85 ± 0,13 μm (Tableau 1). Les valeurs du Dpar ne montrent pas de différence notable de composition chimique entre les échantillons.

Les modélisations de l’histoire thermique indiquent toujours un refroidissement lent après un passage à l’isotherme 110 °C entre 280 et 200 Ma (Fig. 3). Les échantillons les plus hauts (S1 et S2) atteignent la partie supérieure de la ZPE vers 170 ± 10 Ma. En revanche, l’échantillon S3, situé au niveau de la mer, montre un refroidissement extrêmement lent et n’atteint l’isotherme 60 °C que vers 40 à 20 Ma, à la suite d’un dernier épisode de refroidissement bien marqué.

5 Discussion

5.1 L’histoire paléozoïque

Les résultats obtenus sont cohérents avec les données déjà publiées [6,16,44], notamment pour l’histoire Paléo-Mésozoïque. L’exhumation, au Paléozoïque supérieur, des « vieux » échantillons du loch Ness (environ 300 Ma) semble antérieure à celle des échantillons du Ballachulish (360–245 Ma) et du Strontian (280–200 Ma). L’épisode permo-triasique qui affecte les échantillons les plus jeunes (250–175 Ma) est comparable au premier épisode d’exhumation enregistré pour le Strontian (280–200 Ma). Il apparaît donc qu’au Carbonifère supérieur–Permien inférieur, des mouvements verticaux différentiels de part et d’autre de la GGF aient exhumé le Ballachulish, alors que le Strontian restait en profondeur dans la croûte. De tels mouvements ont déjà été rapportés dans la littérature : Rogers et al. (1989) [35], d’après une étude du bassin des Orcades, concluent à entre 15 et 20 km de déplacement horizontal sur la GGF entre le Frasnien supérieur et le Permien inférieur. Ces mouvements sont contemporains d’un épisode compressif, induisant l’inversion de failles normales dans le bassin [10,35,39]. D’autres arguments tels que le plissement post-dévonien de séries sédimentaires [8,11], l’implication de sédiments dévoniens dans la zone de la GGF [39], le plissement et le cisaillement de granites du Dévonien supérieur [39] ou l’enregistrement d’un épisode de compression Permo-Carbonifère dans le Moray Firth [45], viennent appuyer cette hypothèse. Cet épisode compressif carbonifère est probablement induit par une réorganisation des plaques tectoniques durant l’orogenèse hercynienne [39].

Toutefois, la dispersion des âges « jeunes » de part et d’autre de la faille, le long du profil horizontal du loch Ness, laisse penser que ces mouvements verticaux différentiels sont distribués, dans ce secteur, sur toute la largeur de la zone de faille et non localisés sur un accident unique. Cette hypothèse reste à vérifier, car très peu de failles de second ordre, parallèles à la GGF, sont répertoriées. Ce résultat suggère que la distribution de la déformation pourrait varier localement le long du corridor de la GGF.

5.2 L’histoire mésozoïque

L’histoire mésozoïque de l’ensemble des échantillons se résume, après l’épisode de refroidissement rapide au Paléozoïque supérieur–Trias, à une exhumation lente (inférieure à 2 ou 3 km). En faisant l’hypothèse qu’il n’y a pas eu de basculement localisé du Strontian après le début du refroidissement [26], un calcul grossier du gradient géothermique au Mésozoïque moyen peut être fait à partir des échantillons du Strontian. À 160 Ma, les échantillons S1, S2 et S3 sont respectivement aux environs de 60, 70 et 90 °C. Le gradient géothermique, déduit de ces valeurs et de l’écart vertical entre ces échantillons dans la croûte, est d’environ 46 °C km−1. Green et al. [12] donnent un paléogradient de l’ordre de 60 °C km−1 dans des sédiments carbonifères du Moray Firth. Holliday [15] rapporte un gradient de 53 °C km−1 pour les séries jurassiques à crétacées du Nord de l’Angleterre. Un gradient géothermique de 46 °C km−1 implique une dénudation maximale de 2 km entre 160 et 40 Ma environ. Cette valeur est plus faible que les 3 km calculés par les études précédentes [3,31,44]. Elle est cohérente avec l’idée de Hall [13], qui suggère que les principales caractéristiques topographiques des Highlands ont été établies dès le Paléozoïque supérieur–Mésozoïque inférieur, ce qui implique une très faible dénudation au Mésozoïque et au Cénozoïque.

5.3 L’histoire tertiaire

Seuls les échantillons du loch Ness et de Strontian enregistrent l’histoire tertiaire. Ils montrent une forte augmentation du taux de refroidissement à partir de 40 à 25 Ma. Si ce refroidissement n’est que partiellement contraint pour le Strontian (il s’initie en limite de la ZPE), il est clairement exprimé dans les échantillons « jeunes » du loch Ness. Ce refroidissement peut être lié, soit à une activité tectonique induisant de l’érosion, soit à la relaxation du gradient géothermique élevé au Mésozoïque. Le gradient actuel est de 35 °C km−1 [38], soit 11 °C km−1 de moins que la valeur calculée pour le Mésozoïque. Cette relaxation ne peut donc induire que 20 % de « l’exhumation » tertiaire.

Deux épisodes de surrection distincts ont été documentés autour de l’Atlantique nord-est, l’un au Paléogène, l’autre au Néogène [24,25,33]. Le premier est lié à la mise en place du panache mantellique d’Islande. Le second est associé à la subsidence de certains bassins [19], mais les causes sont difficiles à déterminer [2,7,9,25,37]. Toutefois, ces deux événements apparaissent confondus sur nos modèles thermiques. Nous considèrerons donc un seul épisode de refroidissement tertiaire.

Si l’on admet un gradient géothermique de 35 °C km−1, une température initiale de 70 °C, et une erreur de 20°% due à la relaxation post-Mésozoïque, 1,6 km de section ont été érodés depuis environ 40 Ma. Cette valeur est plus faible que les 3 km calculés dans d’autres travaux [6,44]. Toutefois, Thomson et al. [44] notent que moins de 1 km de séries post-jurassiques a été érodé sur les îles de Skye et Raasay, à l’ouest des Highlands.

6 Conclusion

Les traces de fission sur apatite mettent en évidence trois principaux épisodes de surrection/dénudation dans les Highlands d’Écosse. (a) Au Paléozoïque supérieur, des mouvements verticaux différentiels de part et d’autre de la GGF conduisent à l’exhumation du secteur du Ballachulish (Sud de la GGF), jusqu’à des températures inférieures à 60 °C, alors que le Strontian (Nord de la faille) reste en profondeur. Toutefois, localement, le long du corridor de déformation de la GGF, ces mouvements verticaux semblent distribués sur plusieurs failles secondaires parallèles à l’accident principal. Les blocs Nord Highlands et Grampian semblent donc avoir eu une histoire indépendante de surrection verticale au Paléozoïque supérieur. (b) Le fort gradient géothermique calculé à partir des données traces de fission dans le secteur du Strontian pour le Mésozoïque implique une dénudation maximale de 2 km entre 160 et 40 Ma, valeur toujours plus faible que celles calculées précédemment. (c) À partir de l’Éocène–Oligocène, une surrection générale affecte l’ensemble des échantillons, conduisant à 1,6 à 2 km d’érosion, valeur également plus faible que celles déterminées par les études précédentes.

Remerciements

L’auteur souhaite remercier D. Seward, M. Ford et deux relecteurs anonymes pour leurs commentaires constructifs, qui ont permis d’aboutir à ce manuscrit.