Version française abrégée

Introduction

En Europe du Nord-Ouest, les séries cénozoïques possèdent de nombreuses lacunes, expliquées par des déformations compressives intraplaques, qui débutent au Crétacé supérieur, pour se poursuivre durant le Néogène [26]. Les anciens bassins mésozoïques subissent une inversion structurale et leurs massifs anciens (par exemple les Massifs armoricain et cornubien), soulevés, voient leur couverture érodée. Les dépôts cénozoïques sont dispersés à travers le Massif armoricain, mais sont mieux conservés sur les fonds de la Manche et dans ses entrées occidentales [6] (Fig. 1). Le falun constitue un dépôt cénozoïque commun, qui a recouvert périodiquement la bordure armoricaine [5]. Trois épisodes de faluns, datés de l’Éocène moyen, du Miocène moyen et du Plio-Pléistocène, sont ainsi conservés au nord-est du Massif armoricain, dans le Cotentin (Normandie) [17,24], et séparés par de longues lacunes (Paléocène, Oligocène moyen à Miocène inférieur et Miocène moyen à Pliocène inférieur) [7]. Leur étude stratigraphique et sédimentologique permet de discuter l’enregistrement sédimentaire des déformations intraplaques cénozoïques et des transgressions atlantiques à travers la mer de la Manche, le Massif armoricain et le Sud-Ouest de l’Angleterre.

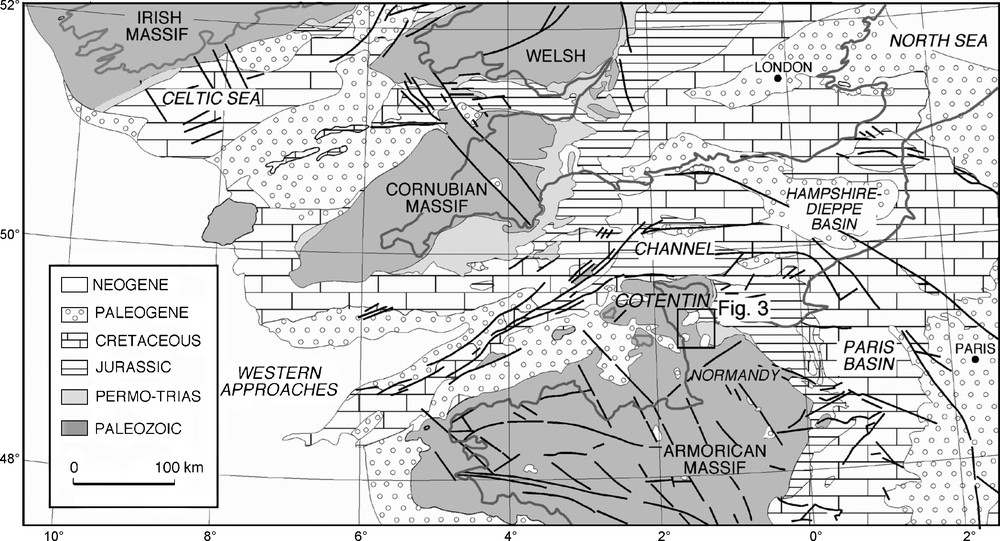

Simplified geological map of northwestern Europe (from [26], modified), showing the position of the Cenozoic Cotentin Basin.

Fig. 1. Carte géologique simplifiée du Nord-Ouest de l’Europe (d’après [26], modifié). Localisation du bassin cénozoïque du Cotentin.

Évolution cénozoïque du Sud-Ouest de l’Angleterre et du Nord-Ouest de la France

L’océan Atlantique a communiqué avec la mer du Nord, par la mer de la Manche, dès l’Éocène inférieur (Yprésien) [10,21]. À l’Éocène moyen (Lutétien), le Sud-Ouest de l’Angleterre (Cornouailles) est érodé, tandis que des faluns transgressifs recouvrent, plus au sud, les reliefs armoricains moins élevés. Un nouveau soulèvement est reconnu entre la fin de l’Éocène supérieur et l’Oligocène moyen, avec des environnements continentaux présents sur tout le pourtour armoricain [10,13,26]. Au Miocène inférieur et moyen, une nouvelle transgression dépose des sables calcaires à bryozoaires sur la façade atlantique du Massif armoricain (Bretagne, Normandie, Touraine et Anjou) ; leur extension est inconnue sur le Massif cornubien [10]. Au Miocène supérieur, un soulèvement du Massif armoricain, décrit en Bretagne, est suivi par un dépôt de sables quartzeux continentaux. Aucun dépôt contemporain n’est connu en Normandie, qui sera inondée dans sa partie occidentale, à la fin du Pliocène supérieur [1,7,8].

Les faluns cénozoïques du Cotentin

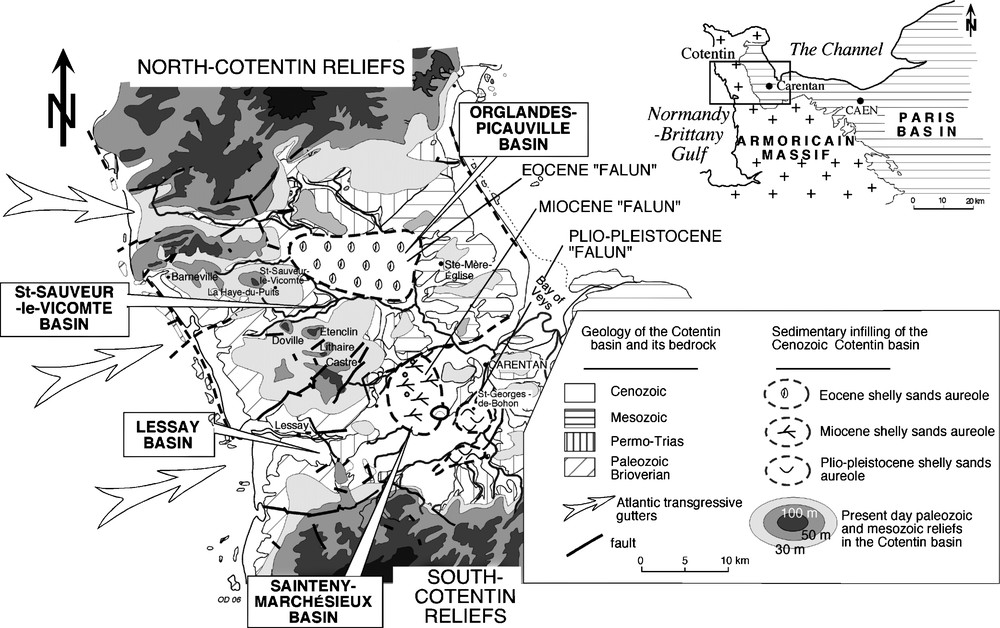

La série cénozoïque située au nord-est du Massif armoricain (Cotentin) (Fig. 2) est connue grâce aux nombreux forages des bassins de Sainteny–Marchésieux, Lessay, Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte et d’Orglandes–Picauville [1,9,22] (Fig. 3). Trois épandages coquilliers cénozoïques recouvrent successivement le Cotentin (Fig. 2), l’un à l’Éocène, avec des sables calcaires à foraminifères (calcaire de Fresville, 20 m, Lutétien à Bartonien) [18], l’autre au Miocène moyen, avec des sables calcaires à bryozoaires et balanes (falun de Bléhou, environ 80 m) [23], et le dernier au Pliocène supérieur–Pléistocène inférieur, avec des sables quartzeux et coquilliers, à lamellibranches et balanes (falun de Bohon, environ 56 m) [7,11].

Vertical synthetic stratigraphic log of the Cretaceous and Cenozoic sequences in the Cotentin, showing the three episodes of the Cenozoic shelly sands (‘falun’), the vertical sedimentological evolution, the transgressions, and the main deformation phases recorded in the Cotentin Basin.

Fig. 2. Coupe verticale synthétique de la série cénozoïque du Cotentin, présentant les trois épisodes de faluns, l’évolution verticale des environnements sédimentaires, les transgressions reconnues dans le Cotentin et les principales phases de compression.

Distribution of the Eocene, Miocene and Plio-Pleistocene shelly sands in the Cotentin. Situation of the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic upland on the western margin of the Cotentin.

Fig. 3. Répartition des faluns éocènes, miocènes et plio-pléistocènes dans le Cotentin. Localisation des paléoécueils paléozoïques et mésozoïques de la bordure occidentale du Cotentin.

Caractères des faluns cénozoïques du Cotentin

Ces trois faluns possèdent des similitudes sédimentaires et une aire de dépôt identique. Ce sont des accumulations de coquilles cassées et transportées par des courants tidaux, décrivant une association de type « foramol » [16,19], sur une plate-forme carbonatée tempérée.

- • Rapports géométriques : l’accumulation maximale des sables éocènes est trouvée au nord (bassin d’Orglandes–Picauville) [2] (Fig. 3). Les faluns miocènes sont surtout conservés plus au sud (bassin de Sainteny-Marchésieux), et les faluns plio-pléistocènes se répartissent en arrière et dans le prolongement sud-est des faluns miocènes. Dans de rares forages, les faluns plio-pléistocènes remanient sous forme de graviers les faluns miocènes [9].

- • Dépôts de haut niveau marin : ces épandages coquilliers marins côtiers cénozoïques correspondent à des périodes de haut niveau eustatique [14], marquant le débordement des eaux atlantiques sur les reliefs armoricains de Normandie.

- • Bassin sédimentaire cénozoïque pérenne du Cotentin : les faluns cénozoïques se répartissent au sud-est, en arrière de reliefs paléozoïques culminant actuellement à une centaine de mètres (monts Castre, Lithaire, Étenclin, Doville et Saint-Sauveur) (Fig. 3). Ces buttes, alignées selon une direction subméridienne, plus ou moins parallèlement à la côte occidentale du Cotentin, ont protégé le bassin cénozoïque, les communications marines avec l’Atlantique s’établissant par des couloirs marins d’orientation varisque N 70.

Les fonds sous-marins subtidaux du golfe Normand-Breton : un exemple sédimentologique actuel

Lors des transgressions atlantiques paléogènes ou néogènes, la courantologie marine dans la mer de la Manche était peu différente de celle connue aujourd’hui, à niveau de la mer équivalent [3]. Un exemple actuel de plate-forme à écueils est le golfe Normand-Breton, avec les îles anglo-normandes et des îlots submergés, contrôlant tout à la fois courantologie, nature et répartition des sédiments et des faunes. Les sables et graviers calcaires s’accumulent en arrière et à l’abri de ces pointements rocheux, constituant des bancs sédimentaires en bannières ou en queue de comète [25]. Cette répartition des sables calcaires est la réplique de ce qui a fonctionné à plusieurs reprises au cours du Cénozoïque, dans le Cotentin.

Le matériel zoogène actuel des fonds littoraux de l’Ouest Cotentin présente des similitudes avec les faluns néogènes et plio-pléistocènes du Cotentin. Les balanes encroûtent les platiers rocheux intertidaux ou faiblement immergés de la côte ouest du Cotentin. Après leur mort, leurs piécettes calcaires, aisément dispersées, s’accumulent formant des bancs coquilliers [15], sous l’effet des courants, autour des îles et îlots rocheux. Les bryozoaires (Cellaria) prolifèrent plus au large, vers –50 m, sur des fonds caillouteux et agités [3]. À leur mort, les squelettes sont transportés vers l’aval courantologique des biotopes, par les courants de marée, entre Guernesey et Jersey, ou stockés dans des bancs sableux coquilliers.

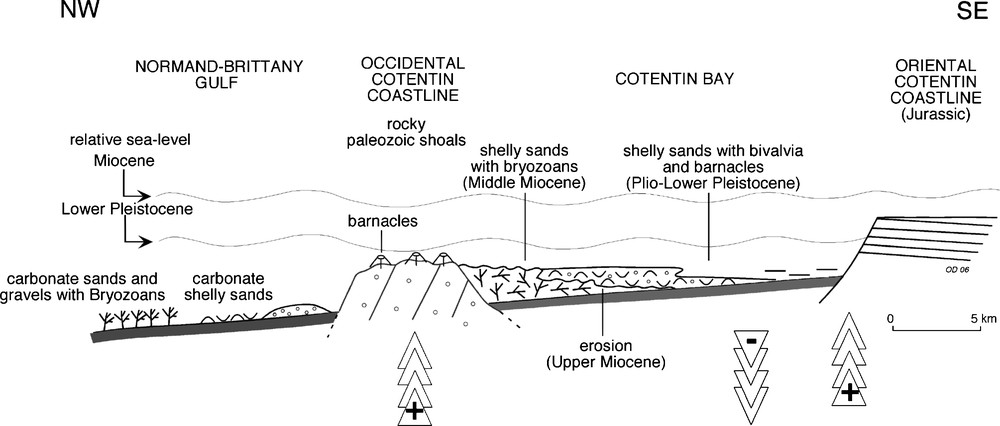

La continuité des aires de dépôt dans le Cotentin, entre l’Éocène moyen et le Plio-Pléistocène, plaide pour une morphologie pérenne du bassin, dès l’Éocène moyen, avec des reliefs précambriens, paléozoïques ou triasiques peu élevés au nord et au sud. Vers l’est, en direction de la baie des Veys, le bassin est fermé durant les émersions de la Manche centrale. Son ouverture sur l’Atlantique se fait par une plate-forme rocheuse peu pentée vers l’ouest, avec des hauts-fonds paléozoïques chenalisant les circulations marines (Fig. 4). Ces écueils influent sur la courantologie et la répartition des sables et graviers calcaires en arrière, dans le bassin du Cotentin. Les fonds sous-marins atlantiques sont colonisés par des bryozoaires au large, des lamellibranches et des balanes sur les plates-formes caillouteuses. Leurs fragments coquilliers sont ensuite transportés en direction du bassin du Cotentin.

Depositional sedimentary model of the Miocene and Plio-Pleistocene shelly sands along a NW–SE transect, and behind the Palaeozoic shoals on the western border of the Cotentin.

Fig. 4. Coupe synthétique NW–SE de la répartition des faluns miocènes et plio-pléistocènes dans le Cotentin, en arrière des paléoécueils paléozoïques de la bordure occidentale du Cotentin.

Évolution cénozoïque du Massif armoricain

La sédimentation du Cotentin est à la fois contrôlée par des variations eustatiques et par les déformations du Nord-Ouest de l’Europe.

Les cycles de transgression/régression cénozoïques

Au moins cinq transgressions cénozoïques sont identifiées dans l’enregistrement sédimentaire du Cotentin [9]. Le premier haut niveau eustatique débute à l’Éocène moyen, déposant des faluns à foraminifères (Lutétien moyen à Bartonien), sans recouvrir la Cornouailles, restée émergée [21]. Puis la transgression rupélienne présente une extension moindre (Argiles à corbules), avec des environnements côtiers à lagunaires peu connus. Une nouvelle transgression débute au Miocène inférieur à moyen, recouvrant de faluns à bryozoaires la bordure atlantique du Massif armoricain et atteignant le Cotentin au Miocène moyen. Après une longue lacune (Miocène supérieur à Pliocène inférieur), la transgression du Pliocène supérieur n’est enregistrée que dans le Cotentin, avec des sables quartzeux à coccolithes [8,11], passant latéralement à des marnes et à des faluns subtidaux. La dernière transgression atlantique reconnue dans le Cotentin est datée du Pléistocène inférieur (Tiglien), avec des sables quartzeux tidaux atteignant la basse vallée de la Seine.

Les déformations cénozoïques du Nord-Ouest de l’Europe

La phase compressive laramide (fin du Crétacé supérieur à Paléocène) est à l’origine des inversions structurales décrites en mer Celtique, dans les entrées de la Manche et en mer de la Manche, ainsi que de l’érosion de la couverture mésozoïque du Massif armoricain [10,26]. Elle est suivie par un soulèvement des bassins du Weald et de la mer Celtique à l’Éocène moyen, alors que des faluns se déposent dans les bassins du Hampshire–Dieppe et du Cotentin.

Une nouvelle déformation débute à l’Éocène supérieur, avec l’inversion des grands bassins mésozoïques (bassin du Hampshire–Dieppe, Bassin parisien et Cotentin, mer de la Manche et entrées de la Manche) (Fig. 1). Dans le Massif armoricain, les déformations à grand rayon de courbure des faluns éocènes créent des dépressions lacustres à palustres (Bartonien) [9,13] (Fig. 2). Sur le pourtour atlantique armoricain et cornubien, les changements paléogéographiques significatifs débutent dès l’Éocène supérieur [10,12]. Les produits d’érosion sont transportés au-delà du talus continental, lui-même incisé par des canyons sous-marins [10]. L’une des plus spectaculaires incisions de la plate-forme armoricaine serait la Fosse centrale, au nord du Cotentin [20]. Elle est interprétée comme un hémi-graben initié par l’inversion des failles d’Aurigny–Ouessant, de direction N 60.

Une autre déformation est datée de l’Oligocène supérieur à Miocène moyen, avec une inversion décrite dans les mers Celtique et d’Irlande, le canal de Bristol, les entrées de la Manche, le Cotentin et le Bassin parisien. Elle n’atteint pas la mer du Nord [26].

Un nouveau soulèvement des Massifs cornubien et armoricain intervient au Serravalien supérieur ou au Tortonien inférieur, stoppant le développement des plates-formes carbonatées armoricaines et incisant la plate-forme bretonne [4]. En Bretagne, des sables quartzeux fluviatiles à estuariens (sables rouges) [4,13] comblent ensuite des paléovallées ; ils sont datés, par la méthode physique E.S.R, entre le Miocène supérieur (Tortonien) et le Pliocène supérieur (Plaisancien), avec une lacune possible du Zancléen [4,13]. Dans le Cotentin, le soulèvement du Miocène supérieur ne s’accompagne pas du comblement définitif du bassin du Cotentin, de nouveau recouvert sous les eaux, au Pliocène supérieur.

Conclusion

La répétition d’épandages de faluns cénozoïques dans le Cotentin et selon des modalités hydrodynamiques comparables démontre la pérennité de ce bassin, entre le Paléogène et le Néogène.

L’inversion structurale paléocène du Massif armoricain explique la surrection de reliefs paléozoïques sur la côte atlantique, puis leur incision fluviatile lors des régressions formant des gouttières étroites et profondes. Ces écueils constituent des protections côtières et canalisent les eaux atlantiques transportant des sables coquilliers, lors des hauts niveaux eustatiques (Éocène moyen, Miocène moyen et Pliocène supérieur).

L’évolution sédimentaire cénozoïque du Cotentin enregistre des variations eustatiques à long terme, modifiées par les phases compressives du Nord-Ouest de l’Europe. Le soulèvement des Massifs cornubien et armoricain au Paléocène–Éocène inférieur, Oligocène supérieur–Miocène inférieur, Miocène supérieur-Pliocène inférieur a favorisé l’érosion des séries paléogènes et néogènes marines du Cotentin, déposées lors des hauts niveaux eustatiques.

1 Introduction

The Cenozoic evolution of western Europe has been dominated by the convergence of the African and Eurasian plates following the Alpine Orogeny [26]. During the Late Senonian and Palaeocene, volcanic activity increased in northwestern Europe (e.g., Norwegian–Greenland rift, Faeroe–Rockall trough) and is associated with the development of the Iceland hot spots. This mantle plume caused thermal uplift over a huge area stretching from the Anglo-Paris Basin, the Channel Basin, the Western Approaches trough to the western coast of Greenland [10,26]. This coincided with intraplate compressional deformation of northwestern Europe, and most of the Mesozoic basins and normal faults were inverted. The development of inversion structures began in Late Cretaceous to Late Palaeocene times and culminated in Oligocene to Miocene times [26].

Consequently, the Cenozoic series in northwestern Europe have long gaps in the rock record, reflecting uplift and folding. As a result, residual Cenozoic sequences are today scattered on the Armorican Massif [24], but better conserved on the sea-floor of the Channel and the Western Approaches trough [6] (Fig. 1). Cenozoic tectonic movements in the Armorican Massif are indicated by the presence of small scattered Cenozoic grabens, but which lack a sedimentary record. The analysis of the Cotentin Cenozoic sedimentary basin allows the interplay between the Atlantic transgressions over the Channel basins and the Armorican border, and the intraplate compressional deformations of northwestern Europe to be understood.

The most common sedimentary Cenozoic facies found in the Channel basins is calcareous shelly sands and gravels (‘faluns’), which were deposited periodically following marine transgression over the Armorican border [9]. Three shelly sedimentary episodes dated to the Middle Eocene, the Middle Miocene, and the Plio-Pleistocene are recorded in the Northeast of the Armorican Massif (Normandy, Cotentin) [9,24]. They are separated by sedimentary gaps (Palaeocene, Middle Oligocene–Lower Miocene and Upper Miocene–Lower Pliocene), but show similar sedimentological features and similar hydrodynamical tidal conditions in the Cotentin. Repetition of these Cenozoic shelly sands demonstrates that the general morphology remained the same in the Cotentin Basin, from the Palaeogene to the Neogene.

2 The Cenozoic evolution of southwestern Britain and northwestern France

Large areas of Cenozoic sediments are preserved offshore from southwestern Britain and northwestern France (Fig. 1). In the Western Approaches and western Channel, the Danian chalks were eroded during a Thanetian uplift. The Eocene is well represented in the centre of the Western Approaches trough and on the Armorican margin [2,6]. During the Early Eocene (Ypresian), a seaway probably extended from the Atlantic Ocean to the North Sea [21]. The uplift of the Cornubian Massif produced an influx of sandy sediments in the Middle Eocene (Lutetian), whereas the marine transgression over the smoother Armorican landscapes deposited bioclastic shelly sands (‘faluns’) that lack clastic inputs.

The Oligocene is absent offshore due to a pulse of Early Oligocene (Late Eocene to Middle Oligocene) uplift, whereas it is well represented to the north of Cornubia [26]. Lacustrine carbonate environments were preserved on the Armorican Massif [4,9]. Following this uplift, the Atlantic Ocean transgressed eastwards. Shallow marine Late Oligocene to Miocene sediments are preserved only on the outer shelf and in the Western Approaches trough. It is not known how far the Oligocene to Miocene marine sequences originally extended towards the Cornubian Massif, but Lower to Middle Miocene shelly sands are found across the Armorican Massif (Brittany, Normandy, Touraine, Anjou) [5,8,13]. In Brittany, the Late Miocene uplift was followed by the deposition of continental quartzose sands. No marine deposits were preserved in Normandy, which was inundated in its northwestern part at the end of the Upper Pliocene by quartzose fine-grained sands [1,8].

3 The Cenozoic carbonate shelly sands and gravels of the Cotentin

The distribution of Cenozoic outcrops is rather patchy in the Cotentin, and the Cenozoic stratigraphy is mainly interpreted from hydrogeological boreholes in which richly fossiliferous sequences are encountered, whose outcrops are often unknown [22]. Precise dating of the Armorican Cenozoic deposits is poor. In the Cotentin, the biostratigraphical data have been summarized and discussed for the Tertiary [9] and the Plio-Pleistocene series [7,11].

Today, the central Cotentin is a marshy area surrounded to the north and the south by Precambrian and Palaeozoic highground and by Jurassic uplands towards the east (Fig. 2). Four kilometre-sized Cenozoic grabens can be distinguished: the Neogene Sainteny–Marchésieux Basin, the Neogene Lessay Basin, the Palaeogene to Neogene Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte Basin and the Palaeogene to Neogene Orglandes–Picauville Basin [17,22].

Three shelly units (Fig. 2) are recorded in boreholes in the Cenozoic sediments from the Cotentin.

The Eocene marine shelly sands, especially rich in foraminifera (‘Calcaire de Fresville’ Fm., 20 m thick, Lutetian to Bartonian) [18], were mainly described in the Orglandes–Picauville Basin, but are also locally recognized to the south and outcrop on the western rocky shore and in the Normandy–Brittany Gulf around the Channel Isles (Jersey, Guernsey). These well-sorted bioclastic and pelletoidal sands are arranged in subtidal sandwaves. The upper part of this Eocene contains peaty lenses with abundant Cerithes, indicating brackish environments. The Lutetian–Bartonian age of these deposits is inferred from the presence of benthic foraminifera [9,18].

The Miocene shelly sands, with abundant bryozoans (‘Falun de Bléhou’ Fm., 80 m thick) [23] are described from boreholes in the Cenozoic basins, from outcrops on the Coutances shoreline and in the Normandy–Brittany Gulf. Very well sorted and homogenous shelly sands rich in bryozoans, bivalvia, gastropods, and barnacles are the major components of these carbonate deposits. The thickness of the shelly sands may reach up to 80 m in the Sainteny–Marchésieux Basin (Fig. 3) [7], without vertical sedimentological changes [9]. They are transgressive on the Permo-Triassic, Cenomanian, or Eocene bedrock. They have been dated to the Middle Helvetian [5,9,24], but isotopic dates give Tortonian ages in Anjou, whereas a radiometric date in Brittany is of Langhian–Serravalian age [13].

The Plio-Pleistocene shelly and quartzose sands (‘Falun de Bohon’ Fm., about 56 m thick) have been described from scarce outcrops in the Sainteny–Marchésieux Basin, but they are recognized in many boreholes from all the Cotentin Basins [8]. The exposures show cross-bedded bioclastic calcarenites to calcarudites that are arranged in subtidal sandwaves that migrated in easterly and northeasterly directions [7]. During the Plio-Pleistocene (Reuverian b to Early Tiglian) [7,11], these subtidal bioclastic sandwaves prograde southwards in the Sainteny–Marchésieux Basin. The ‘Falun de Bohon’ Fm. differs from the underlying Miocene ‘Falun de Bléhou’ Fm. in that it contains a significant content of quartz sands [11]. All the assemblages of barnacles, bivalvia, and brachiopods are of shallow-water marine to estuarine origin.

4 Features of the Cenozoic shelly sands and gravels in the Cotentin

In the Cotentin Basin, most of the Cenozoic shelly deposits are marine, often of tidal origin, but brackish facies also occur at the uppermost of the Eocene sands. These three Cenozoic shelly sands and gravels show many of the same sedimentological features and a same area of deposition, whereas long gaps separated each of them. These are subtidal bio-detrital sands and gravels with accumulation of broken shells that can be described as a ‘foramol’ association of a temperate shelf carbonate [16,19]. The clastic inputs are low in the Palaeogene and the Miocene deposits; the Armorican continental bordering slopes were subdued. The marine Plio-Pleistocene calcarenites are more varied; they are of shallower marine facies than of earlier age, and show increased clastic input. These shelly sands pass laterally into silty marls deposited in an embayment.

Geometrical relationships: the Eocene shelly sands reach their maximum thickness in the Orglandes–Picauville Basin, in the north of the Cotentin Basin [2] (Fig. 3). The Miocene shelly sands with bryozoans are better preserved in the northern part of the Sainteny–Marchésieux Basin, while the Plio-Pleistocene sands were deposited southwards and behind the Miocene shelly sands. In a very few boreholes, the Plio-Pleistocene shelly sands are reworked sands from the underlying Miocene deposits [9]. The same hydrodynamical conditions within tidal currents can explain these three shelly bio-detrital accumulations in a single basin further separated from a few sedimentary basins.

High eustatic sea-level deposits: despite the multiple gaps in the Cenozoic stratigraphic column in Normandy from non-deposition or erosion (Palaeocene to Lower Eocene, Upper Oligocene to Lower Miocene, Upper Miocene to Lower Pliocene) (Fig. 3), the marine shelly sands correspond to repetitive Atlantic sea-level rises of the Cotentin. The relative sea-level rises recorded in the Cotentin series may be correlated with some high eustatic sea levels documented in the long-term Cenozoic eustatic curves [14].

A permanent basin in the Cotentin during the Cenozoic: the three accumulations of shelly Cenozoic sands and gravels were deposited behind the western rocky shoals that at present are over 100 m high (‘Mounts’ Castre Lithaire, Doville, and Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte) (Fig. 3). These Palaeozoic uplands are today devoid of Cenozoic deposits, and their alignment is more or less parallel to the western coast of the peninsula. The communication between the Atlantic Ocean and the Cotentin Basin was established by Cenozoic marine gullies that were orientated N70 in a Variscan direction.

5 Subtidal sea-floor in the Normandy-Brittany Gulf: a modern sedimentological model of Cenozoic shelly deposits

The hydrodynamic conditions in the Cenozoic western Channel were similar to those of the present day, with an equivalent sea level [3,15]. A modern sedimentological example of the Cenozoic Cotentin Basin occurs in the Normandy–Brittany Gulf, whose islands and islets (Normandy–Brittany islands) control the hydrodynamic currents, the nature, and the dispersion of the sediments and of the marine faunas. The wave controlled littoral sedimentation and the tidal currents control the dispersion and deposition of the subtidal sediments and faunas. Between the islands and islets, the tidal currents increase, which explains the occurrence of a rocky sea floor devoid of deposits. The sands and gravels are transported and deposited behind the islets in banner banks [25].

Many similar sedimentological features also exist between the present-day bioclastic materials found in the Normandy–Brittany Gulf and those composing the Cenozoic shelly sands and gravels in the Cotentin Basin. The barnacles, bivalvia, and bryozoans are today the major components of the fragmented shelly sediments. Barnacles colonize and encrust intertidal to near-submersion rocky shores, far away from the western coasts of the Cotentin Peninsula [15]. The fragmented dead barnacles are easily dispersed and transported by currents around islands and islets into shelly sandwaves and into banner banks. The bryozoans (Cellaria) encrust the present agitated hard substratum and reach up to a depth of as much as 50 m offshore on agitated rocky shores [3].

The persistence of the same sedimentary area in the Cotentin and hydrodynamic conditions from the Middle Eocene to the Plio-Pleistocene is an argument in favour of a permanent morphology of the Cenozoic Cotentin Basin. This basin was separated from the Atlantic Ocean by a gently westerly dipping rocky shelf. The Atlantic platform was encumbered with Palaeozoic isles and islets, as today in the Normandy–Brittany Gulf. The origin of this Palaeozoic relief should probably be explained by the repetitive Late Cretaceous–Palaeocene uplifts of the Armorican Massif.

These Palaeozoic rocky shoals controlled the tidal currents and the dispersion of the shelly sands and gravels in the Cotentin Basin. The bioclastic sands and gravels were eroded from the Atlantic platform (bryozoans, bivalvia) or from the encrusted rocky relieves (barnacles) and transported through the marine gully incised into the Palaeozoic substrate, guided by N70 faults. They were deposited behind the upstanding Armorican relief as banner banks on the more protected platforms of the Cotentin (Fig. 4).

In summary, the Cenozoic sedimentary model persisted from the Palaeocene in the northeastern Armorican Massif. This explains the distribution of diverse marine bioclastic sands and gravels of Atlantic origin, transported by tidal currents and deposited into the subsident basin behind the Palaeozoic northwestern coastline of the Cotentin.

6 Discussion: evolution of the Cenozoic Armorican Massif

The Cenozoic sedimentary evolution of lowland Cotentin characteristically records alternating transgression and regression sequences [9] that have been controlled both by global eustatic sea-level changes and by intraplate compressional deformations.

6.1 Cenozoic transgression/regression cycles

The eustatic sea-level changes may have been the most important effect in the Middle Eocene, Middle Miocene, and Late Pliocene in the Armorican Massif, which explains the highstand carbonate sands preserved in the Cotentin Basins.

A total of five transgressions has been identified in the Cenozoic sequences preserved in the Cotentin Basin [9] (Fig. 2). During the first highstand, marine shelly sands dated to the Middle–Upper Eocene (Middle Lutetian to Bartonian) did not reach the emerged Cornubian highground, which was eroded and supplied clastic sediments to the Western Approaches trough [10,21].

By contrast, the overlying next Rupelian marine transgression (‘Argiles à corbules’ Fm.) was less extensive in the Cotentin. Little is known about these near-coastal environments that included brackish lagoon. A subsequent new extensive marine transgression occurred in the Early (Western Approaches) [10] and Middle Miocene (Armorican Massif). The bryozoan sands deposited during this phase covered all the western border of the Armorican Massif [5], but conversely the Cornubian Massif remained emerged.

After a long hiatus (Upper Miocene to Lower Pliocene), the Upper Pliocene marine transgression deposited quartzose sands with coccolithes, which passed laterally into a low-energy bay complex, with subtidal sandwaves. The last marine transgression from the Atlantic resulted in the deposition of the ‘Sables de Saint-Vigor’ Fm. sediments, which were the most widespread and at their maximum extended to Normandy, and probably up to the Seine Valley area. This event is dated to the Lower Pleistocene Tiglian Stage. Apart from its southwestern extremity (Saint-Erth), Cornubia remained emergent during this phase.

6.2 Cenozoic deformations in northwestern Europe

The first Cenozoic compressional deformation is the Laramide phase in the Early Palaeocene, which caused inversion movements in the Celtic Sea, the Western Approaches trough and the Channel basins [26]. The Mesozoic sediments, which covered large areas of the Armorican Massif, were actively eroded at this time [10].

This was followed in the mid-Eocene by uplift of the Weald and Celtic Basins, whereas the Cotentin and the Hampshire–Dieppe Basin subsided (Fig. 1). The Cotentin was inundated by Atlantic marine transgressions from the west, which deposited shelly calcareous sands and gravels (Middle Miocene).

A new compressional deformation began in the Upper Eocene, with the inversion of the major Mesozoic basins (Hampshire–Dieppe, Paris Basin, Channel, Cotentin, Western Approaches trough). In the Armorican Massif, the uplift deformed the Eocene sequences and created hinterland depressions in which lacustrine to palustrine sediments were laid down (Upper Eocene Bartonian Stage) [9,13] (Fig. 2). River incision probably occurred to the west through the Palaeozoic upland, but no Palaeogene fluvial sediments have been found.

In the neighbourhood of the Armorican and Cornubian Massifs, more significant palaeogeographical changes and the deformation took place during the Upper Eocene [5,10,12]. The detrital materials were transported as far as the continental slope, which was also incised. One of the more spectacular incisions of the Armorican shelf would probably have been the Hurd Deep, bounded by the N60° Aurigny–Ouessant faults in the western Channel. The Hurd Deep is a 150 km long, narrow (2–5 km large) and 170 m deep hemi-graben incised into the Mesozoic sequences, which was probably initiated by the structural inversion of the N60 Aurigny–Ouessant faults [20].

A subsequent deformation phase, dated to the Late Oligocene–Mid-Miocene gave rise to an inversion of the Celtic Sea, the Irish Sea, the Bristol Channel, the Western Approaches, the Cotentin Basin, and the Paris Basin; however, subsidence continued in the North Sea [26]. Uplift of the Armorican and Cornubian Massifs took place in the Upper Serravallian to Lower Tortonian. Once again, it stopped the development of the Armorican carbonate platform and caused incision of the Brittany shelf [4].

In Brittany, the quartzose sands (‘Sables rouges’ Fm.) [4,13], dated from Upper Miocene (Tortonian) to Upper Pliocene (Plaisancian) and determined by the ESR method, were deposited in fluviatile to estuarine environments infilled in the palaeovalleys. They include a possible Zanclean hiatus. In the Cotentin, the Upper Miocene uplift did not change the Cenozoic palaeogeography, because the transgression of the quartzose sands is dated later, to the end of Reuverian a (‘Grès de Marchésieux’ Fm.) [11] (Fig. 2)

7 Conclusion

The repetition of shelly sands during the Cenozoic with similar hydrodynamical conditions and sedimentological features demonstrate a continuous morphology in the Cotentin Basin and the same sedimentary model from the Palaeogene to the Neogene. This semi-enclosed marine basin (Eocene to Miocene) was progressively infilled in an embayment that opened westwards into the Atlantic Ocean and closed eastward in the Central Channel (Upper Pliocene). The last Plio-Pleistocene shelly sands partially infilled a bay that opened to the Atlantic Ocean.

The Palaeocene structural inversion would explain the formation of Palaeozoic relief of its western border and allow fluviatile incision with narrow and deep gullies as the fluviatile system developed across the Channel between the Late Oligocene and the Early Miocene.

The Eocene, Miocene, and Upper Pliocene Atlantic transgressions continued up to these gullies and buried the Cotentin beneath shelly sands.

In the Cotentin, the Cenozoic sedimentary evolution reflects the interplay of long-term sea-level oscillations modified by local-to-regional tectonic activity. The regional thermal uplifts of the Cornubian and Armorican Massifs in the Palaeocene–Early Eocene, Upper Oligocene–Lower Miocene, and Late Miocene–Lower Pliocene may have been the dominant periods of activity. These intraplate deformations related to the Alpine Orogeny partially eroded the Palaeogene and Neogene sequences in the Cotentin.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank J.-P. Lautridou and F. Quesnel for fruitful discussions. A. Shrivastava and P. Gibbard reviewed the English version of the manuscript and are gratefully acknowledged.