1 Introduction

Lamprophyres are mesocratic to melanocratic igneous rocks, usually hypabyssal, with a panidiomorphic texture and abundant mafic phenocrysts of dark mica or amphibole (or both) with or without pyroxene, with or without olivine, set in a matrix of the same minerals, and with feldspar (usually alkali feldspar) restricted to the groundmass [24]. Lamprophyres are present in oceanic and continental settings as volcanic, plutonic or sub-volcanic rocks masses. These rocks are a clan of H2O- and/or CO2-rich alkaline rocks, ranging from sodic to potassic and from ultrabasic to intermediate. Commonly, they exhibit a distinctive inequigranular texture resulting from the occurrence of ferromagnesian macrocrysts set in a fine-grained matrix. These rocks provide key opportunities to volatile-enriched (metasomatic) mantle minerals and its dynamic processes. Isotopic composition, source region, mineralogy, tectonic setting and petrological aspects of lamprophyres are discussed by Andronikov and Foley, Guo et al., Riley et al., Seifert and Kramer and Tappe et al. [2,8,22,25,27], respectively.

Lamprophyres are known to occur from Paleozoic to Oligocene in central Iran and they have been produced in different geological tectonic settings [29]. Most of these rocks are volcanic to subvolcanic and have basic composition. In the present paper, which is the first study carried out on the lamprophyres of central Iran, an attempt was made to present geochemical data for a suite of Paleozoic central Iran lamprophyres and to discuss their petrological and geochemical nature as well as their geodynamic setting. Until now, the Paleozoic in Iran is considered as a calm era from the standpoint of magmatism and metamorphism. Thus it is hoped that the data from this small-volume but typical magmatism will be useful in understanding the geodynamical evolution of Iran.

2 Geological setting

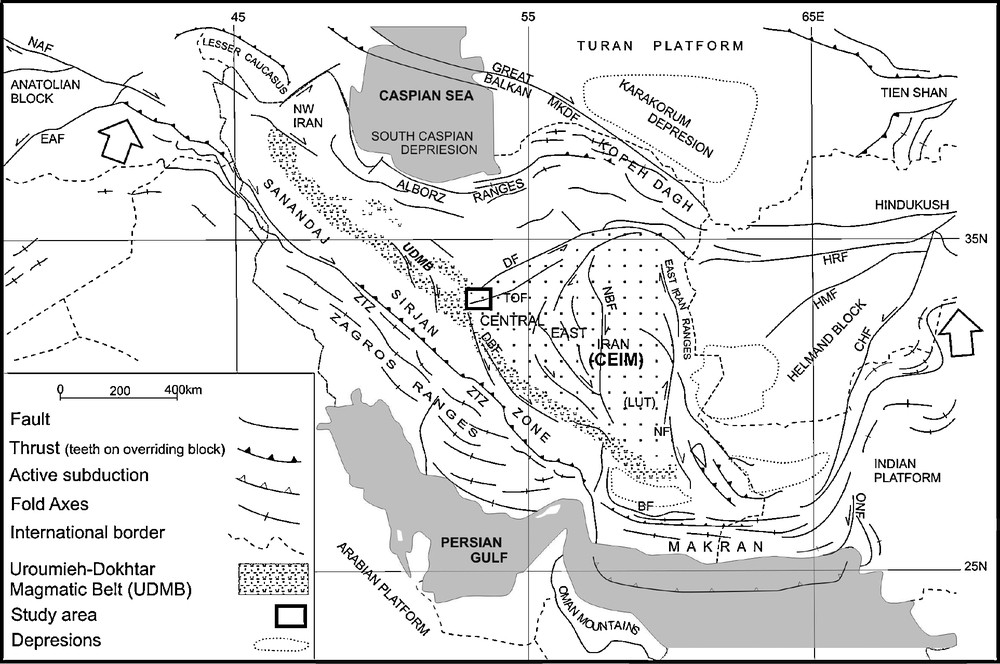

The study area is situated in the western part of the Central-East Iranian microcontinent (CEIM) (Fig. 1), which is bordered by the Doruneh (Great Kavir) fault to the north, by the Dehshir–Baft fault to the west and southwest, by the Bashagard fault to the south, and by the Nehbandan fault to the east. It is surrounded by the Mesozoic ophiolites and ophiolitic melanges that are remnants of Neo-Tethys [29]. This microplate has experienced a severe fracturing manifested by a network of fractures creating a mosaic of blocks moving against each other and created several basins by vertical up and down movements. The occurrence of horst and graben is one of the most important features in this microplate.

Main structural units in Iran and in surrounding areas. BF: Bashagard fault; CHF: Chaman fault; DBF: Dehshir–Baft fault; DF: Doruneh fault; EAF: East Anatolian fault; HMT: Helmand fault; HRT: Heart fault; MKDF: Main Kopeh Dagh fault; NAF: North Anatolian fault; NBF: Naiband fault; NF: Nehbandan fault; ONF: Owen fault; TOF: Turkmeni–Ordib fault; ZTZ: Zagros Thrust zone (modified after Ramezani and Tucker [21]).

Fig. 1. Principales unités structurales en Iran et dans les régions avoisinantes. B.F : faille de Bashagard ; CHF : faille de Chaman ; DBF : faille de Dehshir–Baft ; DF : faille de Dorumeh ; EAF : faille Est-Anatolienne ; HMT : faille Helmand ; HRT : faille de Heart ; MKDF : faille de Main Kopeh Dagh ; NAF : faille Nord-Anatolienne ; NF : faille Nehbandan ; ONF : faille Owen ; TOF : faille de Turkmeni–Ordib ; ZTZ : zone de faille de Zagros (modifié d’après Ramezani et Tucker [21]).

The Turkmeni–Ordib and Doruneh faults that are among the longest, and most prominent, faults of Iran, are very close to the study area. They play an important role in the regional tectonics. The most important geological studies in this area are the following [1,4,28].

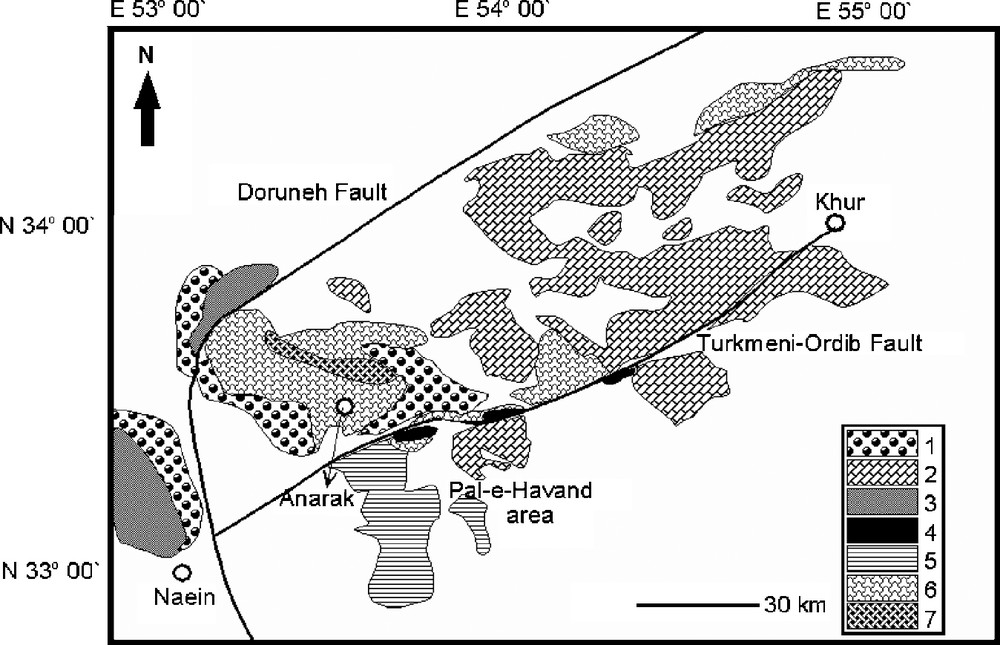

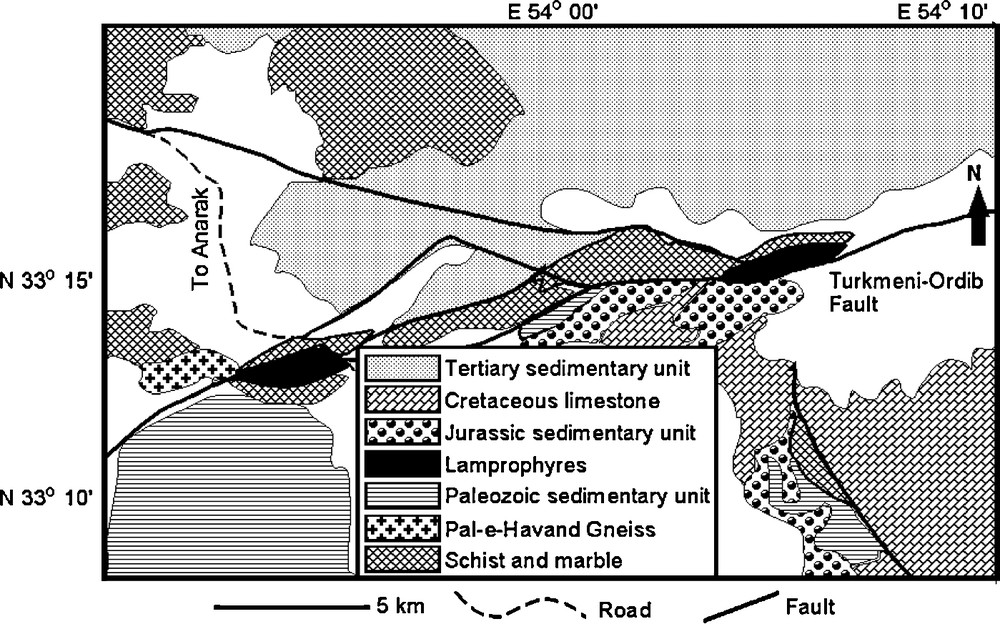

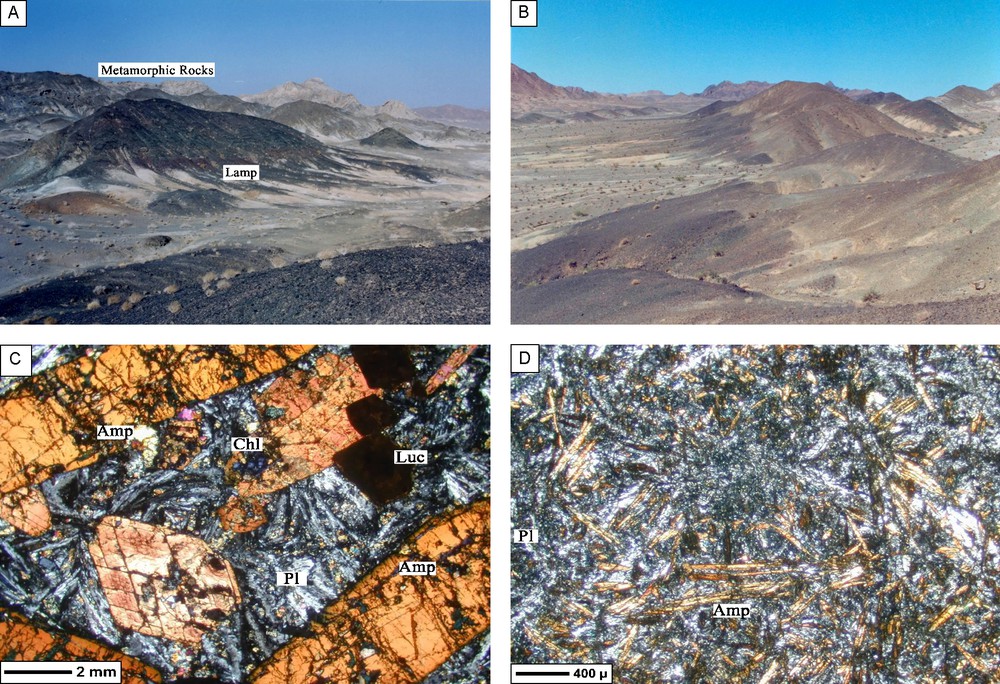

A series of lamprophyric rocks, emplaced as stocks (plugs) crosscutting pillow lavas, occur along the prominent Turkmeni–Ordib fault in the region of Pal-e-Havand (Figs. 2 and 3). Stratigraphically, these lamprophyres belong to the Upper Paleozoic [4]. Investigations on the remnants of Paleo-Tethys subduction proposed 262 and 255 Ma ages (Permian) by U–Pb and Ar–Ar methods, respectively, for the studied rock samples from Pal-e-Havand area. Ribbon chert, minor limestone, and red shale overlie the lamprophyric rocks. These sedimentary rocks and pillow structure of lavas reveal deep sea eruption of this volcanism. The distance between pillows is filled by sediments, glass and volcanoclasts. Size of pillows varies from a few centimeters up to 1 m. A thin layer of sandstone overlying the lamprophyres and covering the sedimentary rocks is made by erosion of Anarak schists and gneisses. The petrological study of these lamprophyric rocks pointed to the significant role of Turkmeni–Ordib fault in Paleozoic magmatism of Central Iran. Field photos of the studied units are shown on Fig. 4 (A and B).

Simplified geological map of the Anarak-Khur area (NE of Isfahan Province, Iran). 1: Tertiary sedimentary unit; 2: Mesozoic sedimentary unit; 3: Mesozoic ophiolite; 4: Lamprophyres; 5: Paleozoic sedimentary unit; 6: Paleozoic metamorphic unit (Anarak metamorphic rocks); 7: Paleozoic ophiolite. The size of lamprophyres unit exaggerated.

Fig. 2. Carte géologique simplifiée de la région d’Anarak-Khur (Nord-Est de la province d’Isfahan, Iran) . 1 : unité sédimentaire tertiaire ; 2 : unité sédimentaire mésozoïque ; 3 : ophiolite mésozoïque ; 4 : lamprophyres ; 5 : unité sédimentaire paléozoïque : 6 : unité métamorphique paléozoïque (roches métamorphiques d’Anarak) ; 7 : ophiolite paléozoïque. La taille de l’unité lamprophyrique est exagérée.

Simplified geological map of the Pal-e-Havand area.

Fig. 3. Carte géologique simplifiée de la région de Pal-e-Havand.

Field photographs and photomicrographs of lamprophyres in Pal-e-Havand area. A. Anarak metamorphic rocks crosscut by stock. B. General view of lavas. C and D. Photomicrographs of lamprophyric stocks and pillow lavas, respectively.

Fig. 4. Photographies de terrain et microphotographies de lamprophyres de la région de Pal-e-Havand. A. Roches métamorphiques d’Anarak, traversées par le manchon lamprophyrique. B. Vue générale des laves. C et D. Microphotographies du manchon et de la lave en coussin, respectivement.

3 Analytical techniques

Mineralogical analyses were conducted by wavelength-dispersive electron probe microanalyzer (EPMA) (Cameca SX-100, at the Institute for Mineralogy, Hannover, Germany and JEOL JXA-8800R, at the Cooperative Centre of Kanazawa University, Japan). The analyses were performed under an accelerating voltage of 15 kV and a beam current of 15 nA. Natural and synthetic minerals of known compositions were used as standards. Representative analyses of the minerals are shown in Table 1. The Fe3+ content in minerals was estimated by assuming mineral stoichiometry.

Chemical composition of rock forming minerals (in wt.%) in Pal-e-Havand lamprophyres (Central Iran).

Tableau 1 Composition chimique (en pourcent du poids) des minéraux constitutifs des lamprophyres dans la région de Pal-e-Havand (Iran central).

| Rock | Mineral | SiO2 | TiO2 | Al2O3 | Cr2O3 | FeO* | MnO | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | P2O5 | NiO | Total |

| Plug | Amphibole | 38.64 | 7.25 | 13.07 | 0.01 | 11.47 | 0.08 | 11.39 | 11.93 | 2.54 | 0.96 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 97.34 |

| Pillow lava | Amphibole | 39.44 | 4.63 | 13.55 | 0.00 | 15.73 | 0.18 | 9.92 | 10.34 | 2.80 | 0.89 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 97.86 |

| Plug | Plagioclase | 67.49 | 0.02 | 19.52 | 0.00 | 0.66 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 11.47 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 99.60 |

| Plug | K-feldspar | 64.62 | 0.02 | 18.10 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.25 | 16.12 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 99.22 |

| Pillow lava | Plagioclase | 67.86 | 0.01 | 19.76 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 1.14 | 11.21 | 0.24 | 0.41 | 0.01 | 100.52 |

| Pillow lava | K-feldspar | 64.32 | 0.01 | 18.38 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 16.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 99.50 |

| Plug | Pumpellyite | 38.22 | 0.13 | 24.42 | 0.02 | 9.97 | 0.20 | 0.02 | 21.97 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 95.21 |

| Plug | Apatite | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 54.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 38.83 | 0.02 | 93.57 |

| Plug | Sphene | 29.14 | 32.96 | 3.51 | 0.02 | 5.91 | 0.05 | 0.77 | 24.70 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 97.23 |

| Plug | Epidote | 37.17 | 0.09 | 21.51 | 0.04 | 13.32 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 19.45 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 91.74 |

| Plug | Chlorite | 25.70 | 0.01 | 18.69 | 0.04 | 35.75 | 0.49 | 7.77 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 88.59 |

| Plug | Ilmenite | 0.04 | 50.31 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 43.63 | 4.16 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 98.52 |

| Pillow lava | Calcite | 0.56 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 4.04 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 51.91 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.41 | 0.01 | 58.33 |

| Plug | Spinel | 0.10 | 3.22 | 27.97 | 20.58 | 37.10 | 0.58 | 9.98 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 99.97 |

| Pillow lava | Spinel | 0.26 | 1.96 | 32.09 | 20.60 | 28.53 | 0.33 | 13.54 | 0.79 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 98.34 |

The major and trace element analyses were carried out on whole rocks at the Activation Laboratory of Isfahan, by NAA method, and in Nancy University (France), by ICP-MS. Twelve samples of pillow lavas and four samples of plugs were selected for analyses. Furthermore, separated phenocrysts of amphiboles were analyzed as an individual sample. Whole rock geochemical data are presented in Table 2. Mineral abbreviations in photomicrographs are from Kretz [11].

Geochemical compositions of Pal-e-Havand area lamprophyres (Central Iran) (Major elements in wt.% and trace elements in ppm).

Tableau 2 Composition géochimique des lamprophyres de la région de Pal-e-Havand (Iran central) (éléments majeurs en pourcent en poids et éléments traces en ppm).

| Sample | Rock | SiO2 | TiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3* | MnO | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | LOI | Co | Sc | V | Zn | Sb | Ta | Hf | Th | La | Ce | Nd | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Tm | Yb | Lu |

| 88-1 | Pl. lava | 40.73 | 4.1 | 15.02 | 15.64 | 0.17 | 7.84 | 7.47 | 2.59 | 2.47 | 3.96 | 85 | 31 | 261 | 122 | 0.48 | 2.42 | 4.74 | 2.89 | 25.79 | 57.23 | 25.59 | 6.59 | 2.14 | 6.48 | 1.02 | 5.20 | 0.95 | 0.37 | 2.03 | 0.30 |

| 91 | Pl. lava | 41.73 | 3.82 | 13.78 | 15.64 | 0.23 | 10.7 | 7.01 | 1.05 | 2.25 | 3.83 | 99 | 35 | 286 | 133 | 0.65 | 2.02 | 4.86 | 2.43 | 17.40 | 36.52 | 16.45 | 4.26 | 1.50 | 4.86 | 0.71 | 4.20 | 0.78 | 0.31 | 1.66 | 0.22 |

| 90 | Pl. lava | 44.16 | 3.57 | 13.93 | 13.67 | 0.14 | 7.87 | 8.12 | 4.26 | 0.67 | 3.61 | 87 | 30 | 291 | 130 | 0.30 | 1.90 | 4.53 | 2.27 | 21.45 | 47.13 | 20.11 | 5.11 | 1.76 | 5.49 | 0.83 | 4.22 | 0.90 | 0.35 | 1.97 | 0.25 |

| 88 | Pl. lava | 45.11 | 3.54 | 12.08 | 15.58 | 0.22 | 9.38 | 7.85 | 1.11 | 1.96 | 3.17 | 94 | 31 | 287 | 126 | 0.39 | 1.94 | 4.84 | 2.29 | 14.98 | 30.70 | 14.17 | 3.96 | 1.42 | 3.96 | 0.56 | 3.16 | 0.68 | 0.30 | 1.90 | 0.31 |

| 92 | Pl. lava | 42.93 | 3.49 | 13.95 | 14.1 | 0.18 | 8.21 | 9.22 | 3.8 | 0.36 | 3.77 | 92 | 28 | 267 | 102 | 0.97 | 2.16 | 4.09 | 2.42 | 17.06 | 39.72 | 17.82 | 4.52 | 1.69 | 5.00 | 0.75 | 4.08 | 1.00 | 0.37 | 2.14 | 0.27 |

| 88-2 | Pl. lava | 43.07 | 3.37 | 15.86 | 12.74 | 0.14 | 7.79 | 7.29 | 3.26 | 2.59 | 3.89 | 69 | 28 | 245 | 94 | < 0.15 | 2.14 | 3.85 | 2.48 | 21.94 | 44.05 | 18.28 | 4.59 | 1.55 | 4.97 | 0.83 | 4.76 | 0.92 | 0.33 | 1.84 | 0.29 |

| 325 | Pl. lava | 47.54 | 3.24 | 13.15 | 13.71 | 0.19 | 5.54 | 10.4 | 3.49 | 0.89 | 1.88 | 61 | 27 | 264 | 78 | 0.24 | 1.83 | 3.75 | 1.85 | 19.93 | 36.42 | 16.00 | 4.03 | 1.60 | 4.83 | 0.81 | 4.26 | 0.78 | 0.30 | 1.49 | 0.24 |

| 314 | Pl. lava | 51.44 | 2.05 | 16.33 | 13.31 | 0.15 | 2.93 | 4.16 | 5.77 | 0.89 | 2.96 | 32 | 9 | 52 | 127 | < 0.15 | 7.21 | 8.92 | 8.27 | 71.73 | 133.81 | 46.61 | 10.79 | 3.56 | 8.35 | 1.33 | 6.17 | 1.08 | 0.42 | 2.73 | 0.36 |

| 99 | Pl. lava | 49.95 | 1.9 | 15.99 | 12.87 | 0.09 | 3.37 | 5.01 | 8.24 | 0.33 | 2.27 | 23 | 4 | 20 | 104 | < 0.18 | 5.99 | 9.81 | 9.50 | 79.11 | 159.30 | 50.27 | 11.10 | 3.08 | 8.68 | 1.45 | 7.40 | 1.40 | 0.47 | 2.84 | 0.39 |

| 95 | Pl. lava | 47.06 | 1.85 | 15.25 | 16.46 | 0.14 | 4.34 | 4.51 | 7.02 | 0.36 | 3.01 | 25 | 5 | 13 | 92 | < 0.16 | 5.16 | 10.72 | 9.61 | 69.59 | 144.97 | 62.52 | 14.86 | 4.57 | 12.33 | 1.67 | 7.70 | 1.40 | 0.54 | 3.28 | 0.52 |

| 89 | Pl. lava | 50.65 | 1.4 | 14.61 | 17.97 | 0.04 | 2.8 | 2.73 | 7.84 | 0.36 | 1.59 | 11 | 4 | 14 | 23 | < 0.15 | 5.12 | 9.75 | 8.83 | 57.94 | 124.21 | 34.53 | 7.80 | 2.48 | 6.83 | 1.29 | 6.79 | 1.21 | 0.51 | 2.90 | 0.38 |

| Var | Pl. lava | 51.6 | 3.04 | 17.71 | 10.71 | 0.07 | 4.36 | 2.41 | 6.33 | 2.43 | 1.34 | 31 | 8 | 56 | 53 | < 0.15 | 4.24 | 7.28 | 6.43 | 51.05 | 103.55 | 30.93 | 7.55 | 2.58 | 8.46 | 1.27 | 5.51 | 1.04 | 0.43 | 2.82 | 0.37 |

| 100 | Plug | 40.39 | 3.75 | 14.89 | 16.41 | 0.21 | 7.29 | 10.3 | 1.29 | 2.23 | 3.27 | 74 | 39 | 554 | 108 | 0.63 | 2.63 | 4.56 | 3.61 | 27.16 | 55.93 | 30.12 | 8.23 | 2.87 | 8.61 | 1.19 | 5.67 | 1.13 | 0.43 | 2.22 | 0.29 |

| 102 | Plug | 44.45 | 4.9 | 16.95 | 11.17 | 0.14 | 5.6 | 8.54 | 3.6 | 2.75 | 1.9 | 37 | 16 | 95 | 100 | 1.51 | 7.02 | 9.76 | 9.29 | 71.09 | 144.80 | 58.49 | 12.30 | 3.53 | 10.96 | 1.53 | 6.29 | 1.20 | 0.41 | 2.37 | 0.30 |

| 316 | Plug | 48.87 | 3.06 | 17.19 | 11.09 | 0.15 | 3.9 | 7.05 | 4.58 | 2.22 | 1.89 | 25 | 7 | 71 | 497 | 0.16 | 6.51 | 10.70 | 8.62 | 68.30 | 150.00 | 69.90 | 13.80 | 4.19 | 10.90 | 1.46 | 7.22 | 1.17 | 0.33 | 1.97 | 0.27 |

| 326 | Plug | 50.99 | 2.17 | 17.75 | 10.17 | 0.15 | 3.32 | 6.56 | 6.5 | 0.48 | 1.92 | 23 | 6 | 62 | 86 | 0.21 | 5.18 | 5.89 | 7.82 | 60.84 | 101.89 | 48.71 | 9.26 | 2.72 | 9.10 | 1.27 | 7.40 | 1.36 | 0.47 | 3.48 | 0.48 |

| F326 | Plug | 49.75 | 1.9 | 18.14 | 10.71 | 0.17 | 3.06 | 6.81 | 5.92 | 0.62 | 2.29 | 26 | 6 | 64 | 117 | 0.34 | 5.50 | 6.36 | 8.12 | 58.60 | 117.00 | 54.70 | 11.20 | 3.42 | 9.94 | 1.49 | 8.24 | 1.53 | 0.54 | 3.37 | 0.49 |

| Min | Amph | – | 9.74 | 14.1 | 17.27 | 0.22 | 9.42 | 10.7 | 2.17 | 1.45 | 2.57 | 67 | 47 | 195 | 180 | < 0.35 | 10.02 | 12.88 | 3.34 | 61.84 | 130.96 | 57.70 | 13.37 | 4.38 | 12.64 | 1.94 | 9.21 | 1.47 | 0.44 | 2.18 | 0.29 |

4 Petrography and mineral chemistry

4.1 Pillow lavas

The studied lamprophyric pillow lavas are dark, brown to green in color. These rocks are porphyritic, microlitic and variolitic in texture. Primary rock forming minerals are plagioclase, amphibole, olivine, K-feldspar, spinel, sphene and ilmenite. Feldspar is predominantly restricted to the groundmass. Chlorite, leucoxene, magnetite and calcite are products of secondary alteration. Calcite amygdals are occasionally present. Leucoxenes are produced by sphene and ilmenites alteration. No fresh olivine has been observed in these rocks; its identity as phenocrysts and microphenocrysts has been inferred from the shape of pseudomorphs and the mineralogy of the alteration products (carbonate and chlorite). Subsea floor metamorphism of pillow lavas has changed the primary calcic plagioclases to secondary sodic ones. Most of amphiboles are fresh, but partly are changed to chlorite. Spinels present absorption texture and a narrow alteration product magnetite rim.

The occurrence of alkali amphiboles (kaersutite) is considered as diagnostic for the alkaline nature of lamprophyric rocks [24]. Different proportions of altered olivine, amphibole and feldspar in studied thin sections present the magmatic differentiation of primary magma. Variolitic texture is produced by rapid cooling of pillow making lava. Microprobe analyses of minerals reveal that amphiboles are kaersutite, plagioclases are albite and oligoclase, K-feldspars are sanidine, and spinels are Cr–Ti spinel in composition. The photomicrographs of studied rocks are shown on Fig. 4 (C and D).

4.2 Plugs

The studied lamprophyric plugs are dark green in hand specimen. The diameter of these intrusions reaches up to 15 m. These rocks are porphyritic and intersertal in texture. The primary minerals of the plugs are plagioclase, amphibole, olivine, K-feldspar, spinel, apatite, ilmenite and sphene. Magnetite, epidote, pumpellyite, chlorite, leucoxene and calcite are produced by secondary alteration. Length of amphiboles and apatite reaches up to 3 cm. Stocks in petrographic studies are uniform and differentiation evidences cannot be observed. Minerals of stocks are more fresh than minerals of pillow lavas. Plagioclases are albite, amphiboles are kaersutite, K-feldspars are sanidine and chlorites are brunsvigite in composition. Percent of pistacite molecules in epidotes is 30%, that calculated as Ps% = 100 × Fe3+/(Alvi + Fe3+).

Petrography and mineral chemistry conclude the similar nature of pillow lavas and stocks. Secondary mineral types reveal that subsea floor metamorphism has occurred in green schist facies. The presence of undoubted relict porphyritic texture, volatile-rich mineralogical composition and alkali amphibole (kaersutite) classifies these lamprophyres as camptonites [20,31]. No mantle or crustal xenocryst or xenolith has been found.

5 Whole rock chemistry

The SiO2 contents of the studied rocks vary from 40 to 52 wt.% (Table 2). The TiO2 and Na2O contents of these rocks reach up to 4.9 and 7.84%, respectively. TiO2 as a HFS element determines the nature of these rocks, but the Na2O content during the subsea floor metamorphism increases whereas the SiO2 and CaO decrease.

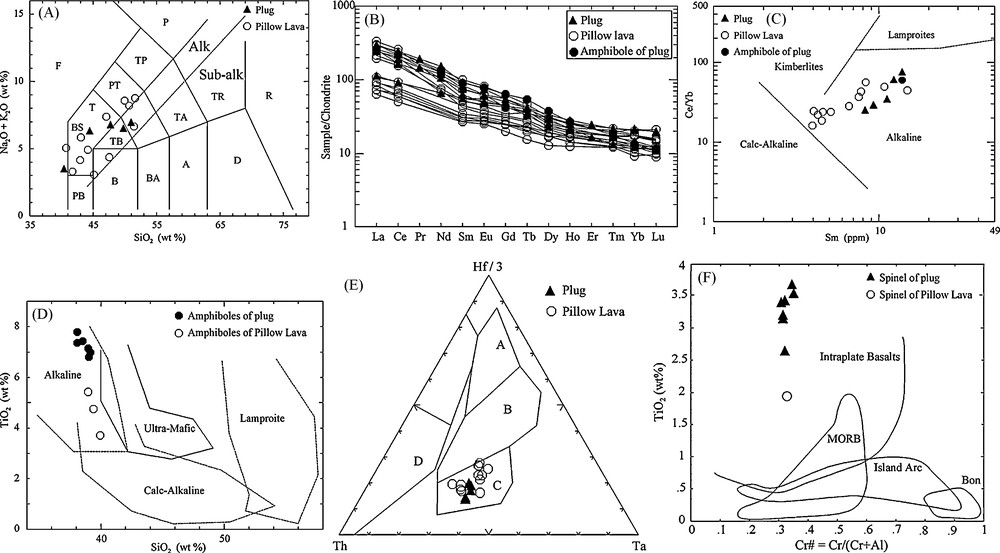

Geochemical diagrams, show that studied stocks and plugs belong to alkaline magmatic series. The plotting of the representative samples on the total alkalis versus silica (TAS) diagram suggests basanite, tephrite, phonotephrite and trachy basalt terms (Fig. 5A). As it is obvious, subsea floor metamorphism and spilitization move the samples situation on TAS diagram to upper parts, but trace and rare earth elements that are resistant, confirm the alkaline nature of these rocks.

Major and trace elements geochemical diagrams for Pal-e-Havand area lamprophyres. A. Total alkalis versus silica (TAS) diagram and classification of the rocks [13]. PB: picrobasalt; B: basalt; BA: basaltic andesite; A: andesite; D: dacite; R: rhyolite; TR: trachyte; TA: trachy andesite; TB: trachy basalt; BS: basanite; T: tephrite; PT: phonotephrite; TP: tephrophonolite; P: phonolite; F: foidite. B. Chondrite normalized REE patterns of the analyzed rocks and minerals. The REE contents of chondrite are taken from Sun and McDonough [26]. C. Classification of lamprophyres by whole rock chemistry [24]. D. The alkaline nature of the lamprophyres is shown by amphibole chemistry [24]. E. Discrimination geotectonic diagram for the studied rocks based on the whole rock chemistry [30]. The analyzed samples lie within-plate alkaline basalt field. A: N-Type MORB; B: E-Type MORB; C: Within-plate alkaline basalt; D: Destructive margin basalt. F. The chemistry of spinels indicates the intraplate nature of the studied lamprophyres [4]. Masquer

Major and trace elements geochemical diagrams for Pal-e-Havand area lamprophyres. A. Total alkalis versus silica (TAS) diagram and classification of the rocks [13]. PB: picrobasalt; B: basalt; BA: basaltic andesite; A: andesite; D: dacite; R: rhyolite; TR: trachyte; TA: ... Lire la suite

Fig. 5. Diagrammes géochimiques d’éléments majeurs et d’éléments traces pour les lamprophyres de la région de Pal-e-Havand. A. Diagramme (TAS) des alcalins totaux en fonction de la silice et classification des roches [13]. PB : picrobasalte ; B : basalte ; BA : andésite basaltique ; D : dacite ; R : rhyolite ; TR : trachyte ; TA : trachyandésite ; BS : basanite ; T : téphrite ; PT : phonotéphrite ; TP : téphrophonolite ; P : phonolite ; F : foïdite. B. Diagrammes des terres rares normalisées à la chondrite des roches et minéraux analysés. Les teneurs en terres rares de chondrite proviennent de Sun et McDonough [26]. C. Classification des lamprophyres d’après la chimie de la roche totale [24]. D. La nature alcaline des lamprophyres est montrée par la chimie des amphiboles [24]. E. Diagramme géotectonique de discrimination pour les roches étudiées, basé sur la chimie de la roche totale [30]. Les échantillons analysés sont dans le champ des basaltes alcalins de plaque. A. MORB de type N. B. MORB de type E. C. basalte alcalin de plaque. D. Basalte destructif de marge. F. La chimie des spinelles indique la nature intraplaque des lamprophyres étudiées [4]. Masquer

Fig. 5. Diagrammes géochimiques d’éléments majeurs et d’éléments traces pour les lamprophyres de la région de Pal-e-Havand. A. Diagramme (TAS) des alcalins totaux en fonction de la silice et classification des roches [13]. PB : picrobasalte ; B : basalte ; BA : andésite ... Lire la suite

Chondrite-normalized REE patterns of the analyzed samples are shown on Fig. 5B. They are 10 to 120 times more enriched in REE than that in chondrite. All the studied rocks are highly fractionated, enriched in light REE relative to heavy REE and exhibit smooth, inclined and parallel patterns and resemble those of mildly undersaturated alkali basalts. No Eu anomaly is observed.

Chondrite-normalized REE pattern of separated amphiboles shows a parallel trend with whole rock data (Fig. 5B).

6 Discussion

Lamprophyres, in contrast to most common rock types, are well known to exhibit heteromorphism viz., their magma composition can crystallize to more than one mineral assemblage under different conditions. Hence, many petrographically distinct lamprophyres can correspond to the same geochemical magma type [12,24]. Thus, the lamprophyres of the studied area are mineralogically similar but texturally variable (porphyritic to aphanitic) yet compositionally (trace and most major elements) they behave as a single group.

Despite their low-grade metamorphism and alteration, most of the major elements, including supposedly mobile elements, of the studied samples still retain the traits of their parental magma. This study, however, reveals that mobile elements (e.g.: K, Na and Ca) display far greater changes than immobile elements (e.g.: Ti, Al and REE) during the alteration and/or metamorphism.

The chondrite REE patterns of all individual lamprophyres are remarkably parallel thereby implying that they were all derived from a similar mantle source region and underwent similar melt extraction.

Rock [24] classifies the lamprophyric rocks into five main groups:

- • calc–alkaline lamprophyres;

- • alkaline lamprophyres;

- • ultramafic lamprophyres;

- • kimberlites;

- • lamproites.

Each group has its own mineralogical and geochemical features.

In the present study, from the minerals compositions, the major and trace elements data and various discrimination diagrams, it can be concluded that the studied rocks are sodic and belong to the alkaline lamprophyre group (Fig. 5C). Chemical composition of the amphiboles confirms this classification (Fig. 5D). The presence of normative olivine and diopside as well as the sodic nature of most of the samples, support the alkaline and undersaturated nature of these rocks [24].

6.1 Source of magma

A number of processes such as contamination of ultrabasic magma with crustal material [15]; extreme differentiation of basic magma enriched in CO2 and H2O [6]; products of low degree partial melting of metasomatized continental lithospheric mantle [23,24] are thought to be involved in the genesis of lamprophyres [20]. Generally more than one process is attributed to have been involved in their origin and emplacement. The field studies, petrography and mineralogy of these rocks and available chemical data propose the elimination of the first and second processes in petrogenesis of these lamprophyres.

The high HFSE contents of the Pal-e-Havand lamprophyres suggest that their source was significantly enriched in these elements, particularly as lamprophyres are generally regarded as products of low degree of partial melting. High concentrations of LREE and high La/Lu ratios observed in these rocks suggest their derivation from very small degrees of partial melting of a garnet lherzolite [10,17]. In order to generate such melts with high LREE and incompatible trace element and abundances, it is also well known that mantle source must have been previously metasomatically enriched [16]. Therefore, metasomatized mantle is the best candidate for a potential source.

The pillow lavas and stocks studied are similar in petrography and geochemistry. Therefore, their parental melts probably derived from the same or very similar asthenospheric mantle sources. These lamprophyres carry the evidence of the presence of an enriched asthenospheric subcontinental mantle component beneath the western part of CEIM in the Upper Paleozoic.

Chondrite-normalized REE pattern of separated amphiboles shows that they are enriched in REE and have same trend with whole rock samples. This reveals that the amphiboles are the main carrier of REE in the studied samples.

6.2 Geodynamics classification

On the basis of tectonic settings, alkaline rock occurrences may be classified into three main categories [5]:

- • continental rift and intraplate magmatism;

- • oceanic intraplate magmatism;

- • alkaline magmatism related to subduction processes (island and continental arcs).

It is well known that lamprophyres reflect their tectonic affinity through geochemical signature [18,19]. Several discrimination diagrams have been tested for the studied rocks to determine their tectonic setting (Fig. 5E and F). Most diagrams suggest a within-plate continental setting. High TiO2 contents (up to 4.9 wt.%) are untypical of subduction zone-generated magmas, whose titanium contents are known to be essentially low (e.g.: less than 1.5 wt.%; [18]). The chemical composition of spinels, as a petrogenetic indicator [3,14], suggests an intraplate geotectonic environment for the studied rocks and confirms the results of whole rock chemistry.

Geological history of CEIM confirms the theoretical data. For an extensive metasomatism of the mantle, at least 24 Ma is necessary [7]. The former subduction of Paleo-Tethys is the cause of volatile enrichment of the mantle and lamprophyric magmatism in Upper Paleozoic. The Paleo-Tethys Ocean spreading in central Iran commenced in Late Ordovician–Early Devonian and terminated in the Late Paleozoic–Triassic [4].

For reconstructions of Late Paleozoic structural elements of the study area, it is clear that the sites of lamprophyric rocks are aligned along the Turkmeni–Ordib fault. In time and space the closest suspected subduction in the surroundings can be related to the Paleo-Tethys Ocean. The former Paleo-Tethys subduction is the cause of the upper mantle deformation and metasomatism.

A widely accepted scenario is that Iran, together with Arabia, was part of Gondwanaland during Precambrian and Paleozoic times, and that there was a northerly migration toward the destructive plate boundary along the southern margin of the Eurasian continent at which the Paleo-Tethys lithosphere was consumed [9]. In the Late Permian or Triassic a major rifting event manifested along the present-day Zagros Thrust zone (ZTZ) (Fig. 1) and broke away the Arabia–Zagros continental mass from the rest of Iranian plate. This continental rift gave way to the southern- or Neo-Tethys seaway, opening of which resulted in closure of the Paleo-Tethys in the Late Permian–Triassic.

7 Conclusion

Based on the combined petrography and geochemistry, the studied lamprophyres are considered to belong to the alkaline lamprophyre category, in general, and camptonites, in particular. The Late Permian pillow lavas and plugs of Pal-e-Havand area display similar chemical composition and they can be the products of low degree partial melting of mantle garnet lherzolites. They belong to within-plate tectonic setting. The chemistry of spinels confirms the results of the whole rock data.

The volatile enrichment of subcontinental mantle of the study area in Late Paleozoic, and lamprophyric magmatism along the Turkmeni–Ordib fault were caused by the former Paleo-Tethys oceanic crust subduction. Late Ordovician to Late Paleozoic subduction of an oceanic crust is too enough for mantle metasomatism and lamprophyric magmatism in the Pal-e-Havand area.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the Isfahan, Kanazawa, Leibniz and Nancy Universities for their cooperation. Reviews of the manuscript by professor J.L.R. Touret and anonymous referee of C. R. Geoscience are gratefully acknowledged.