1 Introduction

Since the middle 1990s, the Mission paléoanthropologique francotchadienne (MPFT) conducts yearly field investigations of the Chad Basin. Four major fossiliferous areas of Neogene vertebrate fauna from the Djurab sand sea (ca. 600 km north-east of N’Djaména) are now published, ranging in age from 7 to 3 Ma: Toros-Menalla, Kossom Bougoudi, Kollé and Koro-Toro [6–10,65]. The outcrops are located in an area extending from about 16°N to 16.5°N and from about 17°E to 19°E.

Details about the tremendously rich vertebrate fauna (mammals, reptiles, birds, fishes) of these localities can be found in the publications of the MPFT team [2,3,23,24,37–41,47]. The study of the evolutive degree of the mammal fauna provides robust biochronological ages. An independent geochronological method, based on the cosmogenic nuclide dating (beryllium 10) of the sediments, recently confirmed the previous chronological framework [34]: Toros-Menalla, 7 Ma; Kossom Bougoudi, 5.2 Ma; Kollé, 4 Ma; Koro-Toro, 3.5 Ma.

Last, but not least, the research of the MPFT team has led to the discovery of two major early Hominids:

- • Australopithecus bahrelghazali (nicknamed Abel; [6,7,30]) which is the first australopithecine found outside the classical early Hominids sites of eastern and southern Africa;

- • Sahelanthropus tchadensis (nicknamed Toumaï; [11–13,29,67]) which is, at this time, the earliest known Hominid.

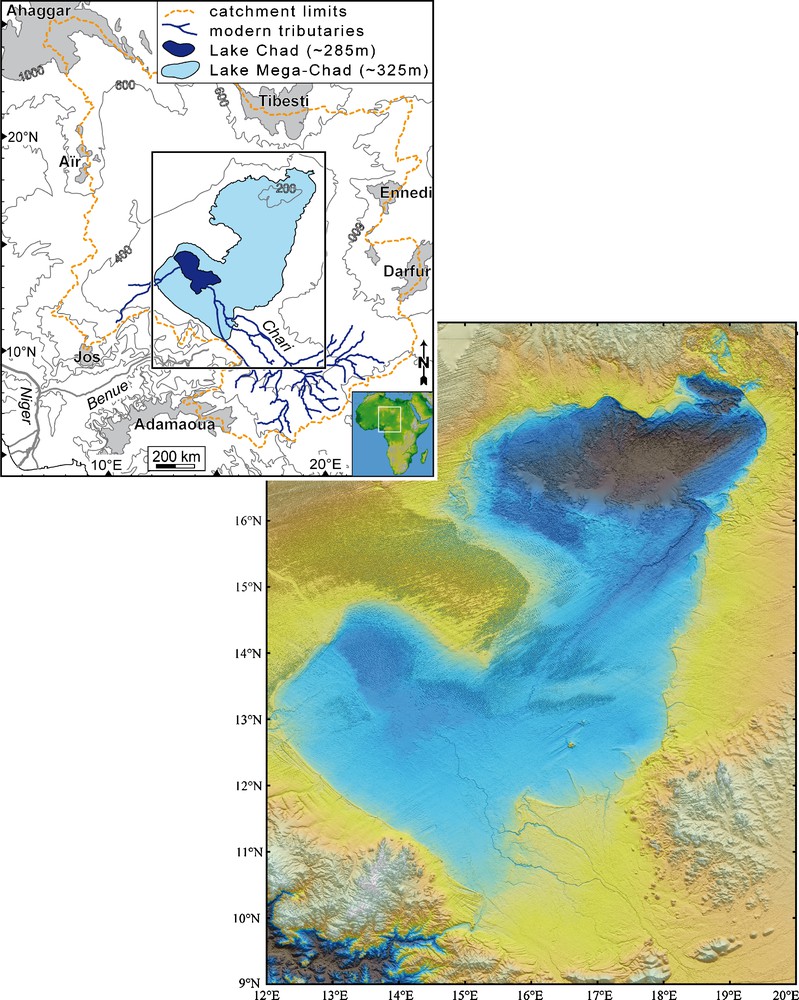

In this article, we present the results of the MPFT's geological investigations in the Chad Basin and examine the paleoenvironments of this area in terms of depositional processes at different scales of time and space. The Mio-Pliocene paleoenvironments of northern Chad Basin are presented with particular focus on the sedimentary archives of the early Hominid levels. The last major paleoenvironmental change that affected the whole area of the basin occurred during the Holocene and is illustrated by a giant paleolake, known as Lake Mega-Chad (Fig. 1).

Location maps showing the Chad Basin, the modern Lake Chad and the Holocene Lake Mega-Chad. Lake Chad is shown here at its largest extension reached during the past few decades. The shaded relief image of the Chad Basin derived from the SRTM3 DEM emphasizes the extension of Lake Mega-Chad (bluish: lacustrine area; yellowish: terrestrial area) and reveals outstanding coastal morphosedimentary features that clearly mark the paleoshorelines. (Image processing by C. Roquin).

Fig. 1. Cartes de localisation montrant le bassin du Tchad, le Lac Tchad actuel et le Lac Méga-Tchad. La scène issue du modèle numérique de terrain SRTM3 surligne l’extension du Lac Méga-Tchad (bleu : surfaces lacustres ; jaune : surfaces terrestres) et révèle les remarquables structures morphosédimentaires littorales qui ourlent le rivage du paléolac. (Traitement d’image par C. Roquin).

2 Geological context

The Chad Basin is an intracratonic sag basin located in North Central Africa. The Neogene and Quaternary sediments [51,60] that accumulated in this basin are supposed to have a maximum thickness of ca. 500 m and a rough extension over an area of ca. 500 km in diameter [14]. Since the last marine episode at the end of the Eocene, the sedimentation in the Chad Basin is only represented by continental deposits; the Oligocene-Miocene time slice being referred to as the Continental terminal [33]. Lake deposits prevail in the sedimentary record since the Late Miocene [53,59]. Contrasting with the expansion of large lake environments during humid periods, recurrent desert episodes also developed in the northern Chad Basin [56].

The Chad Basin basement comprises a suite of crystalline rocks related to the Pan-African orogeny (ca. 750-550 Ma) [33] that are exposed and overlain by younger rocks in several remarkable topographic features marking the border of the basin [66]. To the north, the Cenozoic volcanic rocks of the Tibesti uplift represent the highest mountains in the Sahara (Emi Koussi: 3415 m). To the north-east, Cretaceous sandstones (known as the Continental intercalaire and related to the eastern Africa Nubian Sandstones) compose the tabular plateau of the Erdis (Korko, Dji, Fochimi and Ma; < 800 m). The eastern flank of the basin is bordered by the Paleozoic sandstones of the Ennedi mountains (Basso: 1450 m) and the Precambrian granitoid rocks of the Ouaddaï mountains (< 1100 m). To the South of the basin, the Adamaoua and the Mayo Kebi regions correspond to tectonically active areas related to the Cretaceous-Cenozoic rifting events that affected western and central Africa [28]. To the west, the Late Pleistocene dune field of the Kanem is the only remarkable geomorphic feature. Further afield, the Aïr massif (< 2200 m; Niger), the Darfour mountains (< 3100 m; Sudan), the Bongo massif (< 1500 m; Central African Republic) or the Jos plateau (< 2200 m; Nigeria) represent the extreme extensions of the hydrographic basin of the modern Lake Chad.

This hydrographic basin covers a very large area of ca. 2.5 × 106 km2, extending approximately from 5°N to 25°N and 8°E to 24°E. This huge endoreic basin is partitioned into two sub-basins. The southern one corresponds to the present-day hydrologic basin of Lake Chad, and receives water mainly from the perennial Chari and the Logone rivers draining the humid tropics to the south. The northern sub-basin is presently dry and extends far into the desert. This sub-basin corresponds to a large wind-deflated depression [42] lying at more than 100 m below the deepest part of the southern sub-basin. There, ephemeral river systems originating from the peripheral topographic features (e.g., Ennedi and Tibesti) experience sporadic flash-floods that cannot reach the center of the basin [49]. Detailed descriptions of the modern Lake Chad (climate, hydrology, ecology, populations) can be found in recent publications [46,64]. This lake is very shallow (only a few meters deep) and covers a flat area, therefore, metric lake level variations can lead to lake surface variations of several thousands of square kilometers (e.g., observations of the last decades show that a lake level drop from ca. 284 to 280 m leads to a lake surface decrease from ca. 25,000 km2 to less than 5000 km2). The modern lake level is less than 280 m. Above ca. 285 m, the lake water overflows from Lake Chad into the northern sub-basin via the Bahr el Ghazal valley. This presently dry valley can occasionally be flooded as shown by historical reports [44]. Such water inputs can lead to the development of palustrine-lacustrine environments in the northern sub-basin and, when maintained, to a giant water-body as was the case with the Holocene Lake Mega-Chad presented further in this paper [55].

3 Sedimentary geology of the Mio-Pliocene strata

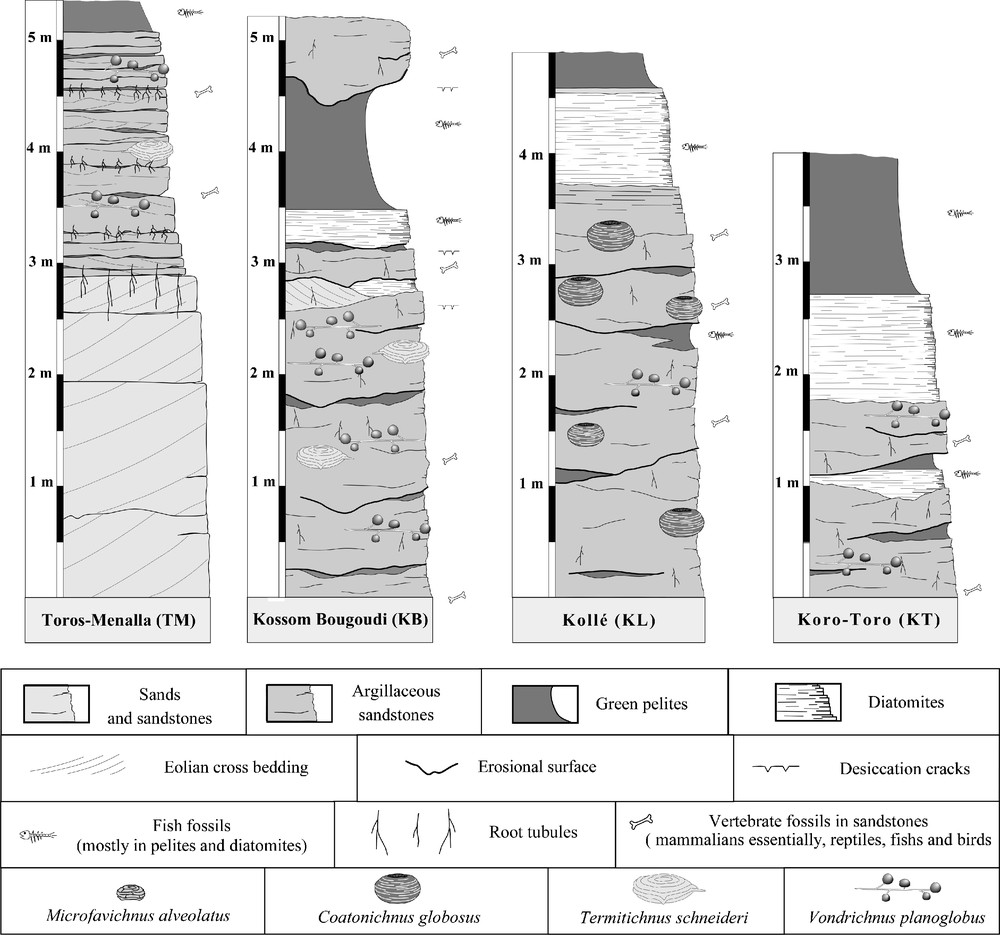

The sedimentary deposits of the four major fossiliferous areas (Toros-Menalla, Kossom Bougoudi, Kollé, Koro-Toro) offer unique insights into the Mio-Pliocene paleoenvironments of the northern Chad Basin. Emerging out of the modern eolian cover, the outcrops consist of large surfaces and small hillocks that were completed by hand-made excavations and locally completed by light geophysical near-surface prospecting with a Ground Penetrating Radar (PulsEKKO 1000 by Sensors & Software) [1,25]. Fig. 2 presents a synthesis of a number of recently published geological sections [10,18–21,52,65].

Synthetic geological columns of the four Miocene-Pliocene fossiliferous areas from the northern Chad Basin.

Fig. 2. Coupes géologiques synthétiques des quatre secteurs fossilifères du Mio-Pliocène du nord du bassin du Tchad.

The sedimentary facies analysis allows distinct depositional environments to be recognized. The occurrence of desert environments is testified by giant cross-stratified sands with grainflow and grainfall laminae preserved in foresets, typical of eolian dune deposits [56]. Open lacustrine environments are marked by laminated or massive deposits of green pelites with diatomite horizons. A transitional environment set between these two poles corresponds to the one where most of the fossil vertebrates are collected. It represents a perilacustrine area [65] where several types of environments of deposition are preserved. The major ones are:

- • progressively fixed, vegetated and/or flooded dunes;

- • paleosol developments with rizoliths and insect nests (see below);

- • ephemeral ponds with pelites to pelitic sandstones;

- • ephemeral river streams and flash-flooded areas marked by massive and matrix-supported pelitic sandstones with desiccation cracks, mud pebbles and erosive bases.

The diversity and dynamic of such depositional environments are mainly linked to climate-controlled fluctuations of the paleolake level. Changes in paleoenvironments in the Neogene of Chad Basin occur at different scales of time and space. First-order changes are evidenced at the scale of each of the geological columns by a recurrent elementary pattern showing climate-driven dry to wet transitions (geographic impact: regional to basin-scale; time duration: probably tens of thousand years and possibly ca. 20 ka if compared to similar sequences in the Quaternary of Chad [45]). Second-order changes are mainly evidenced from all the autocyclic interactions within the perilacustrine area (geographic impact: local to regional; time duration: ranging from a season to several decades, hundreds and even thousands of years).

The Mio-Pliocene terrestrial deposits are characterized by remarkable ichnofossils. These sedimentary structures are linked to biological activity in paleosols and include diverse rhizoliths and complex insect nests. Bioconstructions, such as termite nests and dung-beetle brood-balls, are well preserved and have been exhaustively studied [18,19,20,21,52]. The major results of these studies are:

- • the identification of four new trace fossils of termites (two new ichnogenus and four new ichnospecies) [21];

- • the attribution of the fossil termite nests to two extant termite families (i.e., Hodotermitidae and Macrotermitinae) [21,52];

- • the description of one of the largest insect trace fossils ever described [18,19,21];

- • the study of the first fossil fungus gardens of Isoptera, that represent to date the oldest evidence of symbiotic termite fungiculture [20].

Abundant and various rhizoliths, generally associated with insects trace fossils, clearly mark ancient vegetated areas [21]. Root tubules are represented by tubes (diameter ranging from a few millimeters to a decimeter) of sandstones that generally come out of the outcrops through erosion because of differential cementation along paleoroots. These tubes are either vertical, branching and deeply penetrating or horizontal with concentric layers of cemented sandstones. The coexistence of various types of rhizoliths could reflect plants growing in a seasonally wet and dry climate [5].

Finally, distant volcanic activity is recorded by the presence of in situ grey-blue tephra that accumulated in an area set down of the paleowinds relatively to the Tibesti. The Miocene ashes have a rhyolite mineralogical composition but for the moment, the collected samples were not adequate for absolute dating [32,34].

4 The Holocene Lake Mega-Chad

One of the most striking facets of Holocene climate change in Africa is the occurrence of lakes in the present-day Sahara desert. In the northern Chad Basin, the desert landscape is marked by the omnipresence of lake archives, such as typical sedimentary deposits (laminated diatomites and pelites, coastal sandridges), remains of aquatic fauna (accumulations of freshwater mollusk shells, bones of fishes and crocodiles), or human artifacts (e.g., fishing tools [15]). Observable surfaces of preserved Quaternary lake deposits are estimated to be of ca. 115,000 km2 [33]. The idea of a giant Quaternary paleolake in the Chad Basin raised in the beginning of the 20th century [63], developed during the following decades [22,27,43,48,50,61], but was then questioned [17] as presented in a recent publication [35]. The most complete synthesis of the Quaternary paleoclimate and paleoenvironments of this area has been published by Maley [45].

An original multidisciplinary approach combining remote sensing and fieldwork brought some new and decisive evidences for the existence of the Holocene Lake Mega-Chad [26,54,55], as confirmed by comparable studies [16,35,36]. With a paleosurface of more than 350,000 km2, Lake Mega-Chad (LMC) was the largest Holocene paleolake of the Sahara. Considering its maximum water-level elevation of ca. 320–325 m (controlled by the Benue Trough outlet), its water depth, derived from present-day topography, exceeded 150 m at its deepest zone (i.e., central northern sub-basin) and was around 40 m in the area of the present-day Lake Chad. This large paleolake episode motivated numerical experiments with an Atmospheric General Circulation Model run at high resolution, that show that rainfall was strongly enhanced over the Chad basin at mid-Holocene [58]. Ongoing studies are aiming to unravel the separate roles played by changes in insolation, sea surface temperatures and continental surface conditions in enhancing local water recycling and the northward penetration of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). Schuster et al. [55] identified many significant examples of major ancient coastal geomorphic features and highlighted a number of coastal sedimentary paleosystems distributed all around the LMC reflecting ancient wave-dominated conditions: those include wave-influenced to wave-dominated deltas (notably Chari and Angamma), beach ridges, spits (e.g., Goz Kerki) and wave-cut terraces (Kanem). In modern cases, the morphology of such coastal features is controlled by wind-driven hydrodynamics. As the LMC extended over an area that corresponds to the latitudinal fluctuations of the paleo-ITCZ, these paleoshoreline features represent original archives of paleowind regimes in central Africa. Numerical simulations will help to understand the impact of two contrasted seasonal paleowind regimes (i.e., Monsoon and Harmattan) on the global hydrodynamics in the LMC [4].

Fluctuations of the relative paleolake levels derived from diatoms studies as well as the dynamics of the vegetation derived from pollen studies at the Tjéri type-section (ca.13°44′ N, 16°30′ E) show that lacustrine episodes began after the Last Glacial Maximum but that the highest relative lake levels occurred in the Chad Basin during the Middle Holocene from ca. 8500–6300 years Cal. BP [43,45,48,59,60,62]. The end of this major lacustrine episode is notably recorded by regressive sedimentary bodies in the northern Chad Basin (ca. 16°20′ N, 19° E) at ca. 5 kiloyears Cal. BP [55].

5 Conclusion and perspectives

The Chad Basin, thanks to the outstanding preservation of the sedimentological and paleontological archives, is at this time the only place where the Mio-Pliocene continental paleoenvironments of the Sahara are well documented. It is therefore a unique site to investigate the paleoenvironments of early hominids at decisive steps of their evolution.

The sedimentary record of the Chad Basin since the Late Miocene can be schematized as the result of recurrent interactions between lake to desert environments. But, contrasting with this basic desert-lake pattern, the sedimentary environments of deposition and correlatively the paleoenvironments are very diverse and show important lateral and vertical variations (e.g., open lake, lake shorelines, water ponds, deltas, fluvial systems, soils, dune fields). The distribution and evolution through time and space of the sedimentary depositional environments are here mainly controlled by the climate and influenced by the geometry of the basin.

The major paleoenvironmental changes in the Sahara during the Holocene are the reactivation of river networks and the expansion of lakes. The hydrologic system of the Lake Mega-Chad is one of the most emblematic features of these changes.

Extending the field investigations of the team to the surrounding areas (e.g., Egypt, Libya, Sudan) and prospecting for Mio-Pliocene continental deposits have already started and represent very challenging activities [31,57].

Acknowledgements

We thank the Chadian Authorities (Ministère de l’Education Nationale de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche, Université de N’Djaména/Departement de Paléontologie, Centre National d’Appui à la Recherche (CNAR) : Dr. Baba El-Hadj Mallah), the Ministère Français de l’Enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche (UFR SFA, Université de Poitiers, Agence Nationale de la Recherche – Projet ANR 05-BLAN-0235 ; Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) : Départements EDD, SDV and ECLIPSE), Ministère des Affaires Etrangères (DCSUR, Paris and Projet FSP 2005-54 de la Coopération franco-tchadienne, Ambassade de France à N’Djaména), the Région Poitou-Charentes, the NSF program RHOI and the Armée Française (Mission d’Assistance Militaire [MAM], dispositif Epervier). We thank all of the members of the Mission Paléoanthropologique Franco-Tchadienne, all friends who participated in the field data acquisition and G. Florent and C. Noël for administrative guidance. We kindly thank M. Bano (U-Strasbourg, EOST, CNRS UMR 7516), J.-F. Girard (BRGM, ARN, Orléans) and M. Ferry (U-Evora, Centro de Geofisica) for use of the GPR facilities. We thank L. Foley-Ducrocq for helping us further review the English grammar. Finally, we thank A.-M. Lezine and J. Dercourt for the invitation to the Académie des Sciences.