1 Introduction

The western Alps are characterized by a low deformation rate which makes difficult characterizing their active or Quaternary faults with classical geological and geophysical approaches (e.g., GPS measurements; Walpersdorf et al., 2006). Seismotectonic analyses have shown that the inner Alps are deforming under radial extension whereas the outer Alps are characterized by compression (Sue et al., 1999), but the characterization of active faults through this approach remains exceptional (e.g. the Belledonne Border fault, Thouvenot et al., 2003). Owing to high erosion rates, it has not yet been possible to clearly characterize active deformation in the Subalpine units through geomorphologic studies. To better characterize the recent geodynamics of the Subalpine front of the southwestern Alps, paleostress studies have been focused on the most recent sedimentary units like the Pliocene sediments of the Var valley, and the Mio-Pliocene series of the Valensole Basin (Combes, 1984; Ritz, 1992). In the Valensole Basin, Clauzon (1983) interpreted the deposition of Early Pleistocene screes as the consequence of tectonic deformation and uplift of the Digne thrust sheet. North of this area, in the Digne thrust sheet, Hippolyte et al. (2011) reconstructed a paleo-drainage network infilled with alluvial deposits younger than 3.4 Ma. This paleo-drainage network has been deformed during the Quaternary.

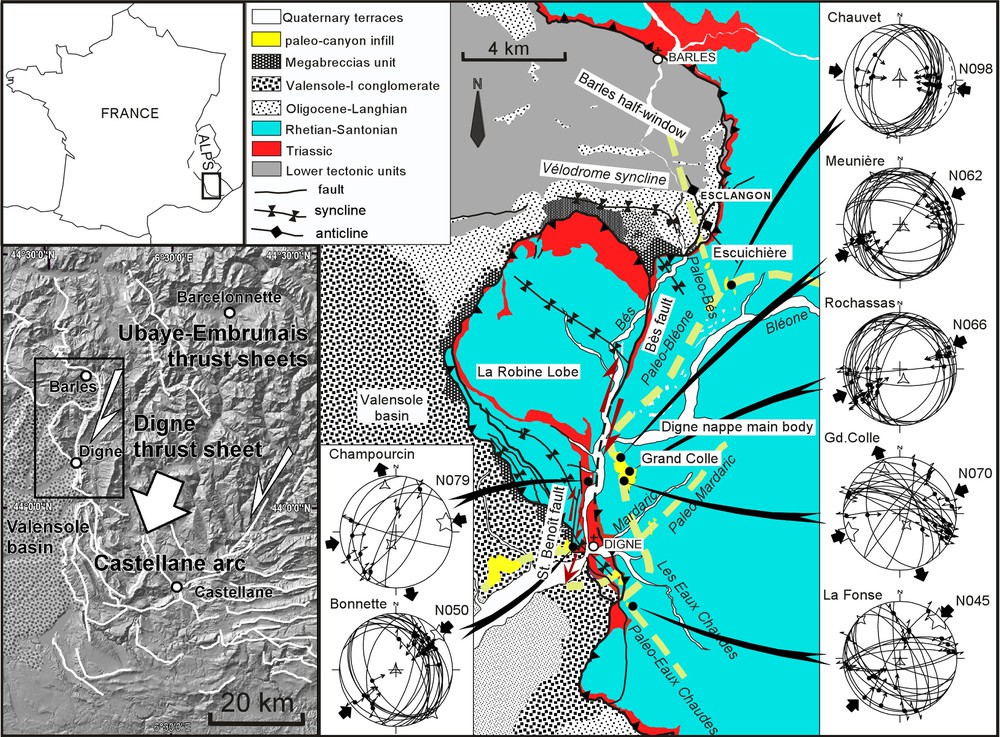

In this article, we present a reconstruction of the Quaternary stress field of the Digne thrust front between Digne and Barles (Fig. 1). Furthermore, we show how combined paleostress and structural analyses can help inferring the location and kinematics of Quaternary faults in a thrust belt.

Location of the study area on a shaded relief view of the Southwestern Alps and structural sketch of the front of the Digne thrust sheet with the Messinian-Gelasian drainage network (yellow dashed lines). Schmidt's diagrams present the striated surfaces measured in the alluvial deposits, with the computed paleostress axes resulting from the fault slip inversions (Angelier, 1990, 1994). Five-branch star = σ1 (maximum principal stress axis); four-branch star = σ2 (intermediate principal stress axis); three-branch star = σ3 (minimum principal stress axis).

Situation de la zone d’étude sur un relief ombré des Alpes du Sud et schéma structural du front de la nappe de Digne avec le réseau hydrographique Messinian-Gélasien (tirets jaunes). Les diagrammes de Schmidt présentent les plans striés mesurés dans les alluvions, ainsi que les axes de contraintes calculés (Angelier, 1990, 1994). Étoile à cinq branches = σ1; Étoile à quatre branches = σ2; Étoile à trois branches = σ3.

2 Geological setting

The Digne thrust sheet is the outermost tectonic unit of the southwestern Alps. It is mainly made of a thick Mesozoic rock sequence, that in places was thrusted over Miocene sediments of the Valensole Basin (e.g. Haccard et al., 1989; Fig. 1). Its décollement level lies in the weak Triassic evaporite layer (Goguel, 1936; Fig. 1). The Digne thrust front extends from the Ecrins external Massif in the north to the east-west trending Castellane Arc in the south (Fig. 1). With the Castellane Arc, it constitutes the southern Subalpine Chains that moved toward the south-southwest (Gidon and Pairis, 1986; Hippolyte et al., 2011). Their western front, along the Valensole Basin, is the dextral oblique ramp of this Subalpine thrust system, whereas the “Arc de Castellane” represents their leading edge (Fig. 1).

The western front (Digne thrust) is characterized by a complex geometry probably because of the influence of Liassic extensional faults on the geometry of subsequent thrusts (Gidon, 1982, 1997; Hayward and Graham, 1989) and also because of its mainly strike-slip dextral motion. Immediately north of Digne, this front shows a salient (La Robine Lobe), which is a large syncline, and a re-entrant, the Barles half-window, corresponding to a large anticline (Fig. 1). In the southern part of the Barles half-window appears a complex syncline of Oligocene-Miocene sediments, named Le “Vélodrome” (Gigot et al., 1974). The “La Robine” Lobe is separated from the main body of the Digne thrust sheet by the Bès fault (Fig. 1). This fault is a recent dextral fault that offsets the leading edge of the Digne thrust sheet near Digne (Gidon and Pairis, 1988; Haccard et al., 1989; Hippolyte et al., 2011; Jorda, 1982).

Several paleostress studies were carried out along the western front of the Digne thrust sheet for determining its geodynamics. Combes (1984) characterized ENE-WSW trends of compression in the Miocene conglomerates of the Valensole Basin. Faucher et al. (1988) measured faults and schistosity in the Digne thrust sheet and concluded for two successive directions of shortening: N30 and N80, respectively. Ritz (1992) also identified two directions of compression, but with a NE-SW compression followed by a north-south compression. In the Barles half-window (Fig. 1), Fournier et al. (2008) found a single trend of compression oriented NNE-SSW. In this article we present the results of a paleostress analysis in the same area (Fig. 1), but in younger (Upper Pliocene-Quaternary) alluvial deposits. The recent age of the alluvial deposits used for fault slip analysis, and of the paleo-drainage network, ascertain that the tectonic deformation and the reconstructed stress field are of Quaternary age.

3 The upper Pliocene-Quaternary alluvial deposits

On the western front of the Digne thrust, Jorda (1970, 1982) and Jorda et al. (1988, 1992) described tectonic deformation in alluvial deposits supposed of Early and Middle Pleistocene age. These outcrops of conglomerate are actually the remnants of the thick sedimentary infill of paleo-canyons that were mainly incised during the Messinian event (Fig. 1; Clauzon, 1999; Hippolyte et al., 2011). During the Messinian salinity crisis, from 5.96 Ma to 5.332 Ma (Gautier et al., 1994; Krijgsman et al., 1999; Lourens et al., 2004), the Mediterranean sea-level dropped by ca. 1500 m, which resulted in deep incision of the peri-Mediterranean rivers including the Rhône and the Durance Rivers (Clauzon, 1979, 1982; Clauzon et al., 1996). At the end of this eustatic cycle, the Mediterranean Basin was refilled, and the lower course of these deeply incised rivers (canyons) was flooded. These rias were progressively filled up with marine sediments, whereas the upper course of the canyons was progressively infilled by alluvial deposits.

This unusual infill of deeply incised canyons resulted in particular sedimentary processes including the aggradation and the retrogradation (upstream) of continental deposits (Hippolyte et al., 2011). In the studied area, this aggradation resulted in a second infill of the Valensole Basin. A Pliocene-Quaternary conglomerate, named the Valensole-II conglomerate, covered most of the Miocene and pre-Messinian Valensole-I conglomerate, and its top surface now forms the Valensole Plateau (Clauzon, 1996; Dubar, 1983). The retrogradation of the continental wedge explains the occurrence of thick alluvial deposits infilling canyons upstream of the Valensole Basin, in the Digne thrust sheet (Fig. 1). Segments of paleo-canyons of all the main modern rivers of Digne were identified: paleo-Bléone, paleo-Bès, paleo-Eaux-Chaudes, paleo-Mardaric (Fig. 1; Hippolyte et al., 2011). At Digne, the base of their retrograding alluvial infill is dated using pollen assemblages between 3.4 and 2.6 Ma (Hippolyte et al., 2011). The age of its top is about 2 Ma according to plant leaves (Jorda et al., 1988), which is in close agreement with the estimated age of the top of the Valensole Basin (Clauzon et al., 1990; Dubar et al., 1998; Hippolyte et al., 2011). Consequently, the incision of the rivers was active in the Alps during the Messinian and the Zanclean whereas downstream, in the rias, it was stopped by the Zanclean flooding. The tectonic deformation of this paleo-drainage network, infilled by Upper Pliocene-Gelasian sediments, is therefore of Quaternary age.

4 Paleostresses

4.1 Data and method

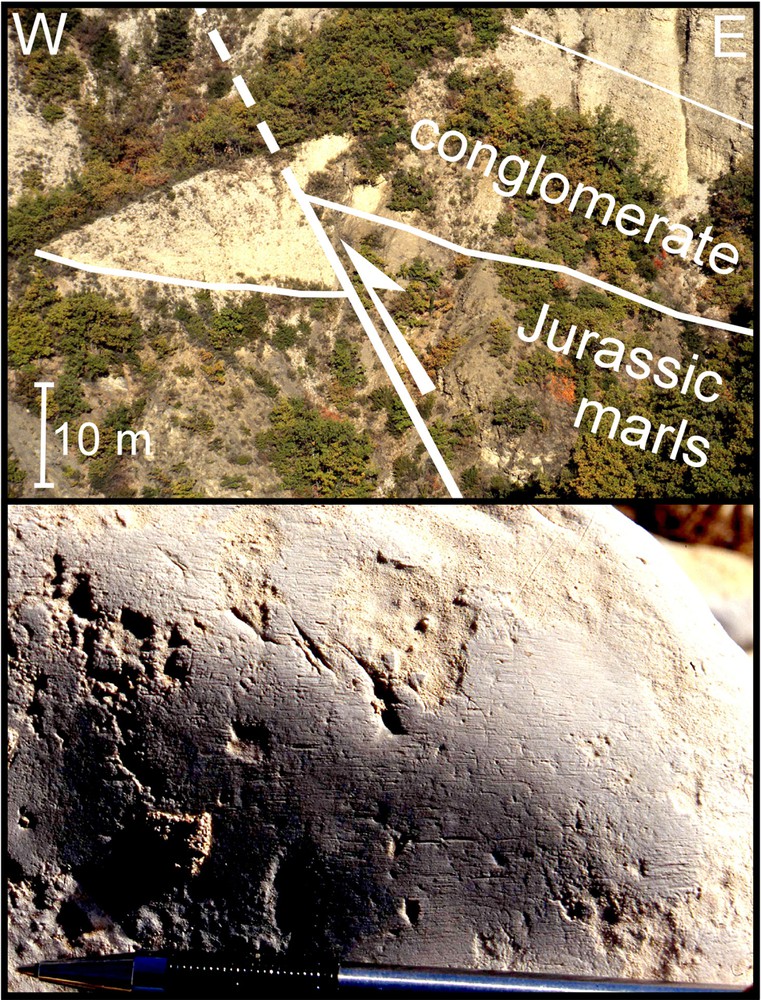

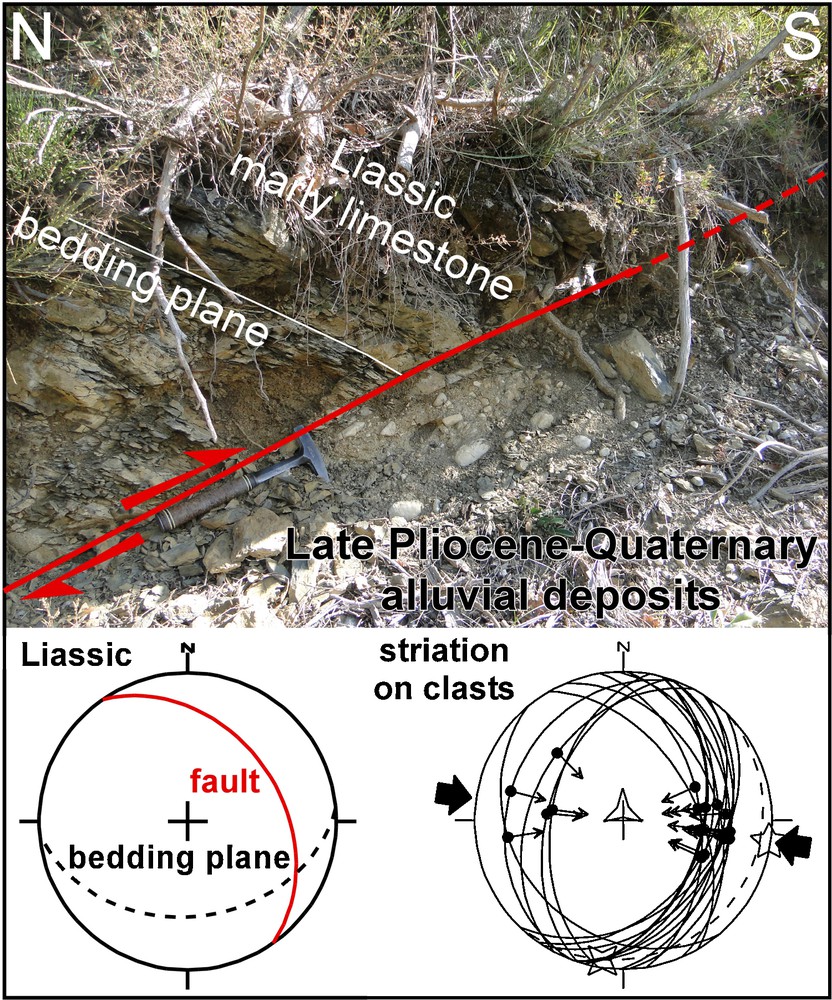

The fault kinematics and paleostress analyses presented in this study are based on measurement of fault slips, in particular in the Upper-Pliocene-Quaternary alluvial deposits. The slickenlines analysed were mainly measured on relatively flat surfaces of boulders and cobbles (Fig. 2). However, we also found faults cutting both the bedrock (Liassic limestone) and the alluvial deposits (Fig. 2). As the geometry of the striated surfaces of clasts is similar to those of the largest fault planes cutting through the conglomerates, these two types of faults are mixed in the dataset. Note that, with the exception of radial striation in sand rich alluvial deposits, previous studies already showed the similarity of the stress inversion results when using striated clasts or consolidated rocks (e.g. Hippolyte, 2001).

Examples of striated surfaces used for paleostress analysis. Upper photo: a reverse fault cuts the base of a paleo-canyon infill at site Meunière (Fig. 1). The striated surfaces are measured in the alluvial deposits. Lower photo: detail of parallel slickenlines on the surface of a clast in the alluvial deposits of site Gd. Colle.

Exemples de surfaces striées utilisées pour la reconstruction de paléocontraintes. Photographie supérieure : une faille inverse coupe la base d’un paléo-canyon au site Meunière (Fig. 1). Les surfaces striées ont été mesurées sur des galets. Photographie inférieure : détail de la surface striée d’un galet du site Gd. Colle.

In the recent sediments of the Digne thrust sheet, striated surfaces of clasts were first observed in the Grand Colle Mountain (immediately north of Digne) by Jorda, 1970, 1982; Fig. 1). We measured fault slips in the sediments infilling the Messinian-Zanclean canyons, but also at the base of the Champourcin alluvial terrace of probable Riss age (Fig. 1; Haccard et al., 1989). In contrast with the very thin slickenlines found in the Quaternary terraces, the striations observed in the infill of Messinian-Zanclean canyons sometimes showed calcite steps and styloliths. The presence of these typical dissolution-crystallisation structures is probably due to the relatively large burial depth and lithostatic charge (for river deposits) that prevailed within these paleo-canyons during deformation. The thickness of alluvial deposits still preserved from erosion is in place up to 100 m, whereas the thickness of the sediments beneath the Upper Quaternary terraces is usually less than 20 meters in this area (Hippolyte et al., 2011).

We used the Angelier's sofware to compute the orientation of the three principal stress axes (σ1, σ2 and σ3) and a shape ratio (σ) of the stress tensor (Angelier, 1990, 1994). The inversion results are presented in Table 1, and the fault diagrams are shown in Fig. 1.

Résultats des inversions de contraintes ; diagrammes de failles de la Fig. 1. σ1, σ2, σ3 : direction et plongement des axes de contraintes principales respectivement maximales, intermédiaires et minimales. σ = (σ2–σ3)/(σ1–σ3). Critères de qualité : ANG (angle moyen en degrés entre la contrainte cisaillante calculée et la strie observée) et RUP (0 ≤ RUP ≤ 200) (Angelier, 1990).

| Site | Number of faults | σ1 | σ2 | σ3 | PHI | ANG | RUP | |||

| Trend | Plunge | Trend | Plunge | Trend | Plunge | |||||

| Champourcin | 8 | 79 | 10 | 201 | 71 | 347 | 16 | 0.16 | 21 | 42 |

| Bonnette | 21 | 50 | 0 | 140 | 0 | 249 | 90 | 0.29 | 10 | 32 |

| Chauvet | 18 | 98 | 1 | 189 | 5 | 357 | 85 | 0.60 | 8 | 20 |

| Meuniere | 25 | 242 | 2 | 332 | 6 | 134 | 83 | 0.34 | 10 | 38 |

| Rochassas | 23 | 66 | 2 | 335 | 16 | 162 | 74 | 0.32 | 15 | 47 |

| GD. Colle | 20 | 250 | 3 | 150 | 71 | 341 | 19 | 0.08 | 11 | 32 |

| La Fonse | 21 | 45 | 4 | 315 | 4 | 177 | 85 | 0.01 | 11 | 34 |

4.2 Reconstruction of the paleostress field

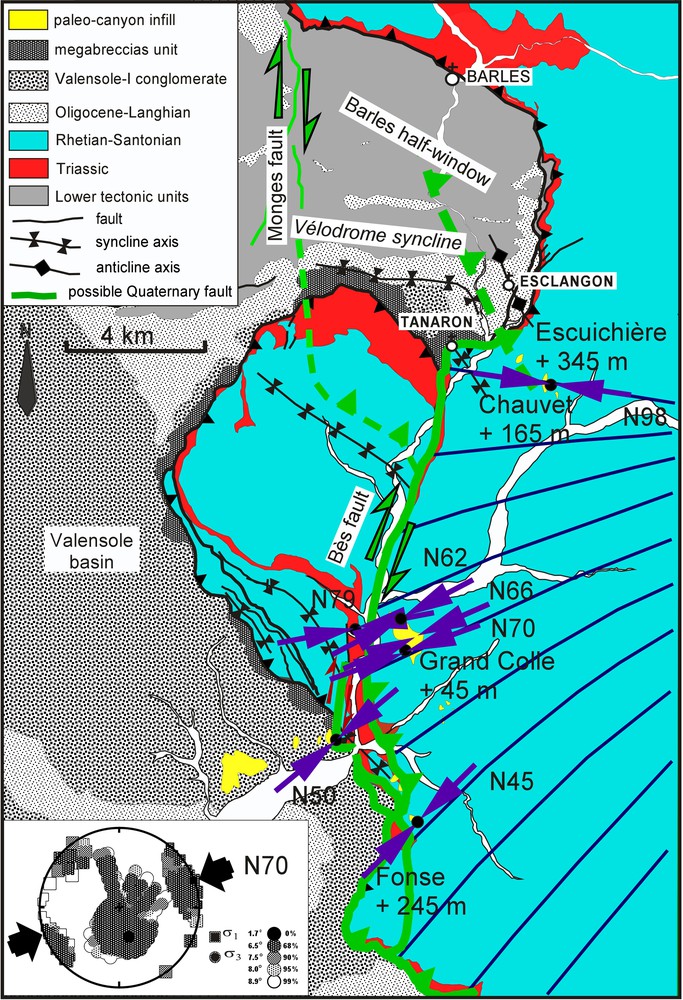

The distribution of the outcrops of Upper Pliocene-Quaternary alluvial deposits allowed fault analysis along the Bès and Saint Benoît faults (Fig. 1). The Quaternary deformation resulting from the slip on these faults was already characterized using the elevation of the thalweg of the paleo-canyons (Hippolyte et al., 2011). These dextral faults cut and displaced laterally the paleo-canyon of the Bléone River by about 2.3 km at a slip rate of 0.7 mm/yr (Fig. 1, Hippolyte et al., 2011). North of Digne, the Bès fault trends N15E and its slip is mainly along-strike as shown by the low vertical displacement (+ 45 m) of the Blèone paleo-canyon at Grand Colle (thalweg at 790 m; 160 m above the modern river) relative to its elevation in the Valensole Basin (thalweg at 696 m; 115 m above the modern river) (Fig. 3). Around Digne, this fault turns to a NW-SE strike and branches on the Saint Benoît fault and on thrusts ramps that uplifted the thalweg of the paleo-Eaux Chaudes River by 245 m (Pliocene-Quaternary thalweg at 1010 m elevation at site Fonse; Fig. 3).

Quaternary stress field deduced from the calculated orientation of the σ1 axis. Double arrow = calculated trend of σ1. In green the faults probably active during the Quaternary (Bès fault, Esclangon and Tanaron blind thrusts). The tectonic uplift of the segments of paleo-thalweg in the Digne thrust sheet is computed taking into account the elevation of the Bléone paleo-thalweg in the Valensole basin and the modern river profiles. The stress deviations are compatible with the dextral strike-slip movement of the Bès fault. The diagram shows the best fitting stress model from focal plane mechanisms of the Digne area using the exact method of Gephart and Forsyth (1984) and the average misfit values associated with each confidence limit (Hippolyte, 2001). Masquer

Quaternary stress field deduced from the calculated orientation of the σ1 axis. Double arrow = calculated trend of σ1. In green the faults probably active during the Quaternary (Bès fault, Esclangon and Tanaron blind thrusts). The tectonic uplift of the segments of ... Lire la suite

Champ de contraintes Quaternaire déduit de l’orientation de σ1 calculée à partir de plans striés. Double flèche = direction de σ1. En vert, les structures probablement actives au Quaternaire (faille du Bès, chevauchements aveugles d’Esclangon et de Tanaron). Le soulèvement tectonique des segments de paléo-thalweg dans la nappe de Digne est calculé par rapport au paléo-thalweg de la Bléone dans le bassin de Valensole et à la pente des rivières actuelles. Les déviations de directions de contraintes sont compatibles avec le mouvement dextre de la faille du Bès. Le diagramme présente un résultat d’inversion des mécanismes au foyer de séismes de la région de Digne (Hippolyte, 2001) en utilisant la méthode Gephart et Forsyth (1984). Masquer

Champ de contraintes Quaternaire déduit de l’orientation de σ1 calculée à partir de plans striés. Double flèche = direction de σ1. En vert, les structures probablement actives au Quaternaire (faille du Bès, chevauchements aveugles d’Esclangon et de Tanaron). Le soulèvement tectonique des segments ... Lire la suite

We measured striations at six sites in the alluvial deposits of these paleo-canyons along the Bès and Saint Benoît faults. In contrast, we have not observed any tectonic striation in the sediments of the Blèone paleo-canyon west of site Bonnette (Fig. 1). All fault sites along the Bès and Saint Benoît faults show strike-slip to reverse fault slips in agreement with the strike-slip to reverse motion on these main faults (Fig. 1).

On the eastern side of the Bès fault, in the three sites of the Grand Colle Mountain, the computed trends of compression are similar and ranged between N62°E and N70°E (Figs. 1 and 3). To the south the trend of compression rotates counter-clockwise to N45°E at La Fonse. North of Grand Colle, at site Chauvet (Fig. 3), the trend of compression rotates clockwise to N98°E. All the sites showed monophase deformation and the formations are too young to interpret these large variations of the trend of compression (53°) as the result of rotation of faulted blocks during the strike-slip deformation. Therefore, we interpret these variations of the trend of σ1 as “stress deviations” (Rebaï et al., 1992; Rispoli, 1981).

It is well known that variations in maximum stress direction can occur along strike-slip faults (e.g. Homberg et al., 2004; Lacombe, 2012; Rispoli, 1981). At Digne, our paleostress analysis suggests a perturbation of the stress field in agreement with the motion of the Bès fault that is mainly dextral on its N15-trending portion (Fig. 3). A similar stress deviation may occur along the Saint Benoît fault, where the trend of compression rotates from N79E at Champourcin, to N50E at Bonnette (Fig. 1).

4.3 Origin of the stress deviations

Stress perturbations occur generally at the extremities of faults (e.g. Homberg et al., 2004; Lacombe, 2012; Rispoli, 1981). Near the southern extremity of the Bès fault, the counter-clockwise stress rotation at La Fonse occurs where the fault changes of strike and dip to become an oblique thrust (Fig. 3). On its northern tip, the Bès fault does not cut Le Vélodrome syncline (Fig. 1) and we can infer that, in a similar way, its motion is transferred to thrusting. That the strike-slip motion of the Bès fault ends in Le Vélodrome syncline is in agreement with the clockwise rotation of σ1 at Chauvet (Fig. 3). Finally the recent stress field reconstructed is in agreement with the dextral strike-slip motion of the Bès fault between Digne and Le Vélodrome syncline. The way this strike-slip motion ends in Le Vélodrome syncline is discussed below.

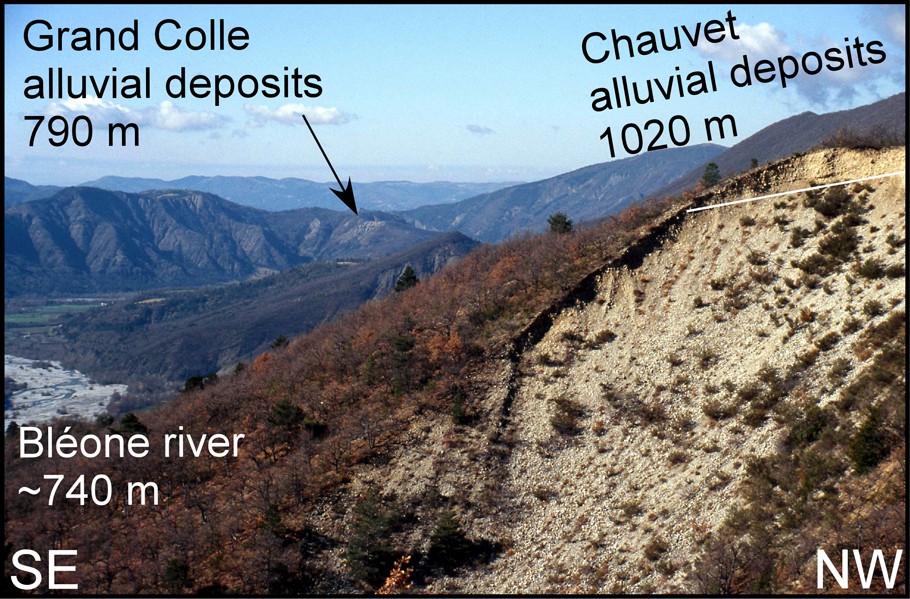

At Chauvet, the alluvial deposits are about 100 m thick and the paleo-thalweg is at 1020 m elevation, 280 m above the modern Bléone River (Fig. 4). This elevation is partly related to thrust deformation as suggested by the tilt of these alluvial deposits to the southeast, and their tectonic deformation (Figs. 4 and 5). Compared with the thalweg of the paleo-Bléone river in the Valensole Basin immediately west of Digne, 115 meters above the modern Bléone River, the thalweg at Chauvet has been uplifted of 165 m (Fig. 3). Note that we quantify an uplift that occurred after the incision of the paleo-canyon at 3.4–2.6 Ma (Hippolyte et al., 2011). Another segment of this paleo-drainage network is present to the northwest of Chauvet at the Escuichière pass (Fig. 3). There the thalweg of the paleo-Bès river is at 1200 m elevation and was uplifted by 345 m (Figs. 3 and 6). This area of the Digne thrust sheet is therefore characterized by the highest uplift rate recorded by the paleo-drainage network of Digne (between 0.10 and 0.13 mm/yr).

View looking to the southwest of the 100 m thick alluvial deposits at Chauvet on the Barles anticline (Fig. 3). The alluvial deposits are tilted about 10° toward the southeast. They are about 100 meters thick and the elevation of the paleo-thalweg is 1020 meters.

Vue vers le sud-ouest de l’affleurement de conglomérats du site Chauvet sur l’anticlinal de Barles (Fig. 3). Les alluvions sont basculées d’environ de 10° vers le sud-est, elles sont épaisses de près de 100 mètres et le paléo-thalweg est à 1020 mètres d’altitude.

Tectonic superposition of Liassic limestones on the Upper-Pliocene-Quaternary alluvial deposits of the Bléone paleo-canyon at site Chauvet (northern border of the paleo-canyon, Fig. 3). Striations were not preserved at this place and the reverse fault slips shown in the fault diagram are measured on the other side of this outcrop (Fig. 4).

Faille inverse portant les calcaires du Lias de la nappe de Digne sur les alluvions du Pliocène supérieur-Quaternaire du paléocanyon de la Bléone à Chauvet (bordure nord du paleo-canyon, Fig. 3). Les stries n’étant pas conservées à cet endroit, les plans de faille inverse présentés sur le diagramme ont été mesurés de l’autre côté de l’affleurement (Fig. 4).

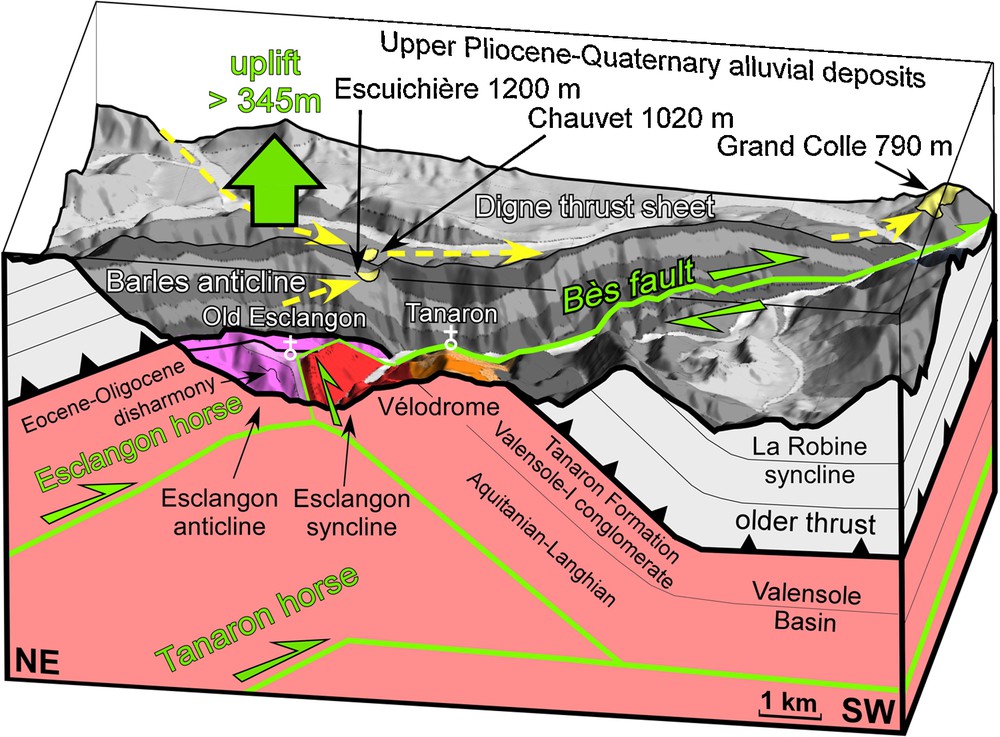

3-D view, looking to the southeast, of the Quaternary front of the Digne thrust sheet, and subsurface structural model. Geological map draped over digital elevation model with × 2 vertical exaggeration. Probable Quaternary faults are in green. Whereas the sub-vertical Bès fault displaces in dextral sence by ∼2.3 km the Bléone paleo-canyon at Digne (near Grand Colle), it is not mapped north of Vélodrome. To take into account the termination of this dextral motion near Le Vélodrome, the stress perturbation, the reverse fault at Chauvet, and the > 345 m uplift of the paleo-canyon at the Escuichière pass, we propose that the strike slip motion on this fault is transferred northward and downward to NNW-trending and NW-trending intercutaneous thrust wedges, the Esclangon and the Tanaron horses. During the Upper Pliocene-Gelasian, the incision of the paleo-Bès river had already reached the Oligocene formations beneath the Digne thrust sheet. We infer that the folding of the Digne thrust sheet (Barles anticline) had begun before the Upper Pliocene. Masquer

3-D view, looking to the southeast, of the Quaternary front of the Digne thrust sheet, and subsurface structural model. Geological map draped over digital elevation model with × 2 vertical exaggeration. Probable Quaternary faults are in green. Whereas the sub-vertical Bès fault ... Lire la suite

Vue 3-D vers le sud-est du front Quaternaire de la nappe de Digne et modèle structural de sub-surface. La carte géologique est drapée sur un MNT avec une exagération verticale de 2. Les failles d’âge probable Quaternaire sont en vert. Tandis que la faille du Bès décale de prés de 2,3 km le canyon de la Bléone à Digne (près de la Grand Colle), elle ne semble pas se poursuivre avec la même géométrie au nord du Vélodrome. Pour expliquer l’amortissement du mouvement dextre de la faille du Bès dans le secteur du Vélodrome, la perturbation de contraintes, la faille de Chauvet, et le soulèvement des paléo-canyons au col de l’Escuichière et à Chauvet, nous proposons que son mouvement décrochant soit transféré vers le nord et en profondeur sur des chevauchements récent de direction NNW-SSE et NW-SE, correspondant aux unités d’Esclangon et de Tanaron. Au Pliocène supérieur-Gélasien, la rivière du paleo-Bès a déjà incisé la nappe de Digne jusqu’aux roches d’âge Oligocène que l’on retrouve dans le remplissage des paléo-canyons. On en déduit que le plissement de la nappe de Digne avait débuté avant le Pliocène supérieur. Masquer

Vue 3-D vers le sud-est du front Quaternaire de la nappe de Digne et modèle structural de sub-surface. La carte géologique est drapée sur un MNT avec une exagération verticale de 2. Les failles d’âge probable Quaternaire sont en vert. ... Lire la suite

The uplift of the paleo-thalweg at the Escuichière pass confirms that the strike-slip motion on the Bès fault is not accommodated north of this site by the Digne thrust. Effectively, beneath the Escuichière pass, the Digne thrust dips to the south, and a southward displacement of the Digne thrust sheet on this south-dipping thrust contact would have lowered the elevation of the paleo-thalweg (Fig. 6).

In this area, the Digne thrust sheet has been anticlinally folded and the erosion of this anticline has produced the Barles half-window (Fig. 3). The uplift of the paleo-canyons is much probably related to this folding (Fig. 6). However, this anticline and a tectonic window partly existed in the Upper Pliocene-Gelasian because the alluvial deposits infilling the canyons contain clasts of Oligocene rocks eroded from the autochtonous of the Barles area, in particular at the Escuichière site that is a segment of the paleo-Bès canyon (Hippolyte et al., 2011; Jorda, 1970, 1982; Fig. 1). Moreover, the southern limb of the Barles half window is juxtaposed across the Bès fault, with a syncline of the Digne thrust sheet (Figs. 1 and 6). Therefore, the Barles anticline is a complex structure that cannot be explained by the activity of a single subsequent thrust. We propose a structural model to explain how the Quaternary strike-slip motion on the Bès fault is transferred to uplift in the Escuichière area.

At Chauvet, a reverse fault brought the Liassic limestone above the Upper Pliocene-Quaternary alluvial deposits (Fig. 5). This fault trends NW-SE and dips to the northeast (Fig. 5). Along its strike, Le Vélodrome syncline is a complex structure with two fold axes east-west and NNW-SSE (Fig. 1) probably resulting from two phases of folding (Gidon and Pairis, 1992). Its NNW-SSE trend corresponds to the eastern limb of the Esclangon syncline (Gidon and Pairis, 1992) but also to the western limb of the Esclangon anticline (Fig. 6). The location of the Esclangon anticline, beneath the southeastern part of the Barles anticline in the Digne thrust sheet (Fig. 6), together with the NW-SE trend of the reverse fault at Chauvet (Fig. 5), suggests that its formation or its reactivation has participated to the uplift of the paleo-canyons (Fig. 6).

To take into account the stress perturbation and the termination of the dextral motion on the Bès fault in Le Vélodrome area, the trend and structure of the Esclangon anticline, the recent NW-SE reverse fault at Chauvet, and the highest Quaternary uplift of the Digne thrust sheet at the Escuichière pass, we propose that, to the north, a part of the dextral slip of the Bès fault is transferred to a blind thrust below the NNW-trending Esclangon anticline (Figs. 3 and 6). We name the unit that tilted the eastern edge of Le Vélodrome syncline (Fig. 5) the Esclangon horse. Its emplacement was partly accommodated by a passive roof thrust as suggested by NW-trending disharmonic folds in the Eocene-Oligocene sandstone and marls (Fig. 6).

Our model does not exclude the activity of another blind thrust that may participate to the accommodation of the Late Pliocene-Quaternary ∼2.3 km right lateral displacement of the Bès fault (at > 0.7 mm/yr, Hippolyte et al., 2011). West of the Bès fault, a major recent thrust has tilted the Miocene series of the Vélodrome syncline and the overlying Digne thrust sheet, and has created the La Robine syncline (Fig. 6). We name this deep-seated NW-SE structure the Tanaron horse (Fig. 6). It was emplaced after the deposition of the Valensole-I conglomerate and Tanaron Formation (after the Messinian, Fig. 6), and probably partly existed in the Upper Pliocene because the paleo-Bès river incised the Oligocene sandstone of the Barles half-window (Fig. 1). It may branch to the West on the right lateral Monges fault (Gidon and Pairis, 1992; Fig. 3).

The Tanaron horse, with its passive roof thrust, transferred the right lateral displacement of the Bès fault to the west (Fig. 3). The two horses participated to the uplifted by more than 345 meters the Digne thrust sheet and the paleo-canyons above the Barles Anticline (Figs. 3 and 6).

5 Conclusion

Paleostress analysis from striation in Upper Pliocene-Quaternary alluvial deposits allowed us to characterize the Quaternary stress field of an oblique strike-slip thrust front. The deformation of the recent deposits is monophase but is characterized by stress perturbations. We infer that the various trends of compression determined in some previous fault studies in older rock formations along this dextral-reverse thrust front, might result from stress perturbations and not necessarily from successive phases of the Digne thrust sheet emplacement. The NNE-SSW trend of compression found by Fournier et al. (2008) in the Valensole-I conglomerate of the Vélodrome syncline could be related to the formation of the Barles anticline and the emplacement of the Tanaron horse. Despite the large (53°) deviation of the trend of compression near Digne, paleostress analysis is found useful to reveal the recent activity of the Bès Fault and of deep intercutaneous thrust wedges, the Esclangon and the Tanaron horses. The proposed structural model allows taking into account all the characteristics of the Quaternary deformation along the Digne thrust: location of the deformation, variation in the trends of compression, highest uplift rate of the paleo-canyons. In conclusion, this study underlines the interest of combining fault kinematics studies in recent rock formations with regional structural analyses to characterize the recent geodynamics of low deformation rate areas.

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to Georges Clauzon for constructive discussions. We are thankful to Dr. Damien Delvaux and Pr. Marc Fournier for their constructive reviews.