1 Introduction

The large-scale oceanic circulation over the continental shelf of the Gulf of Lion (NW Mediterranean Sea, Fig. 1) is induced by the regional component of the cyclonic general circulation of the western Mediterranean basin, namely the Northern Current. Strong atmospheric fluxes typical of this region (Hauser et al., 2003) play an important role in inducing local actions, e.g. upwellings (Millot, 1990) or eddy structures, that can interact with the Northern Current (Estournel et al., 2003; Hu et al., 2009; Rubio et al., 2009). This hydrodynamic behaviour is highly variable and sometimes difficult to represent with a simple model.

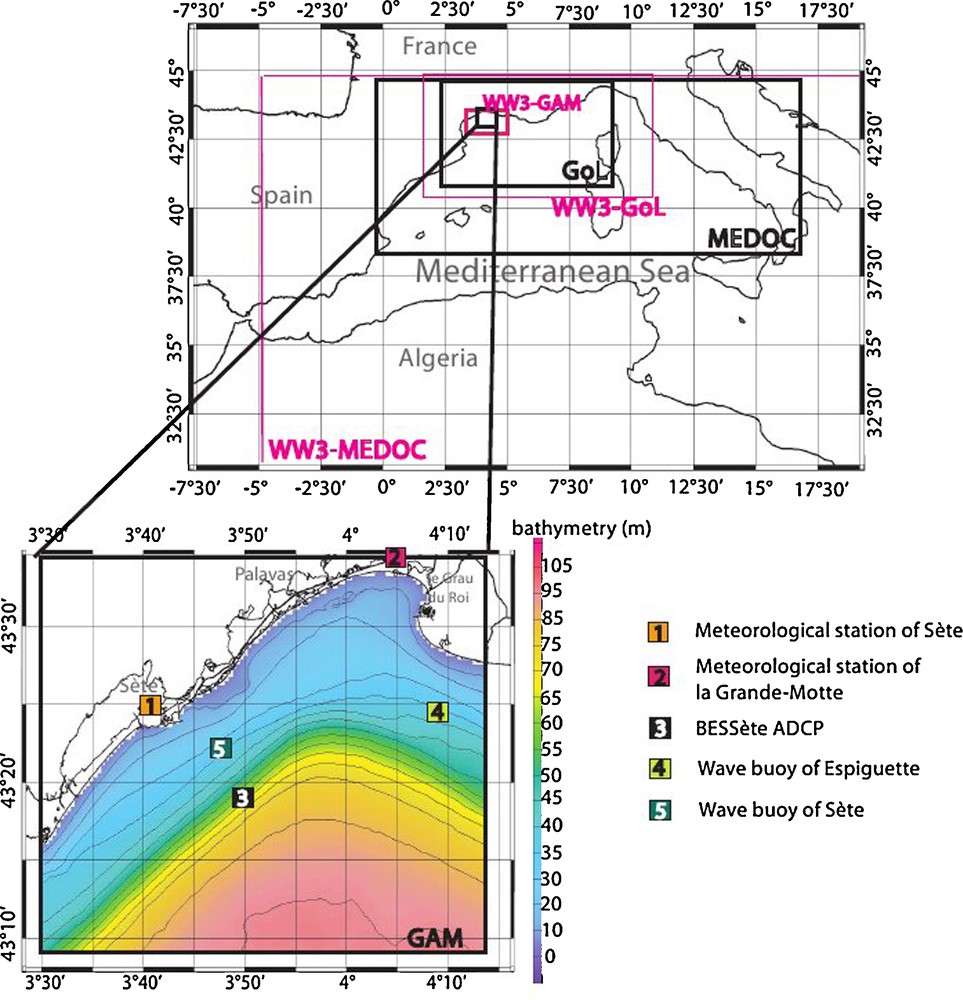

Modelling strategy: The three embedded domains used by SYMPHONIE (black frame) and WW3 (red frame) and locations of the BESSète station, the meteorological stations and the wave buoys.

Numerical models of coastal oceanic circulation using primitive equations are nevertheless quite representative of the majority of observed currents when they are constrained by realistic conditions (in particular atmospheric and large scale forcings), (Bouffard et al., 2008; Ourmières et al., 2011; Pairaud et al., 2011). For example, the studies by Leredde et al. (2007), carried out in the northern sector of the shelf, i.e. in the Gulf of Aigues-Mortes (GAM, Fig. 1), demonstrated that the SYMPHONIE model faithfully reproduced the observations, which were made mainly with a hull-mounted ADCP during the 9-day HYGAM cruises. They showed how the full picture produced by the model improves our understanding of the observations. In the case of northerly wind (Tramontane or Mistral) or calm or light south-easterly wind conditions, observations and models indicate that surface currents never exceed 0.4 m . s−1 close to the surface and 0.2 m . s−1 on the bottom. This hydrodynamic behaviour rarely gives rise to significant sediment transports and bottom shear stresses remain weak. However, sediment transports and sea-floor shearing effects are known to be significant during stormy periods characterized by strong swells (Ferré et al., 2008; Ulses et al., 2008a). Such events are, however, very difficult to observe, as they require the installation of permanent observation stations. In the Gulf of Lion, such experiments have been carried out in zones relatively close to the coast (Grémare et al., 2003; Guillén et al., 2006). The middle and outer parts of the shelf are monitored much less often, mainly because of the difficulties of maintaining equipment in such exposed regions. Our knowledge of the currents and bottom stresses in large areas of the shelf is thus limited.

In February–March 2007, a recording station was installed at 65 m of water depth. This station, called BESSète (Bottom Experimental Station of Sète), was equipped with an ADCP that made continuous measurements of the wave parameters and current vertical profiles. On 18 February 2007, a south-easterly stormy period occurred, characterized by a swell with significant heights greater than 5 m during which the BESSète station measured strong currents, with intensities larger than 0.6 m . s−1, over the whole water column parallel to the shore. The aim was then to identify the source of this powerful circulation and also to check whether this behaviour was correctly reproduced by the circulation model (SYMPHONIE). The current speed simulated by the model was observed to be underestimated and two possible sources of misrepresentation were investigated: a lack of wave forcing on the current and an underestimation of the wind speed. Some sensitivity experiments were performed and theories on the cause of the strong observed currents are discussed below.

The paper is organized as follows: the experimental setup and the numerical models are presented in section 2. Then, section 3 describes the measurements and section 4 the different simulated results during the storm period. Section 5 proposes some theoretical discussions of the mechanisms responsible for the strong observed current. Finally, Section 6 provides a summary and conclusion.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental setup

The BESSète station was an automatic current and wave measuring station, installed at a bathymetric depth of 65 m, to the south-east of Sète (France) (Fig. 1). Located at 3° 50′E, 43° 19′N, this station was equipped with a bottom ADCP (RDI 300 kHz) with a wave module. The ADCP was configured to measure the current every 30 min, with a vertical resolution of 2 m, and the sampling rate for the wave characteristics was set to 8 min every 3 h. In addition, the wind field was measured every hour at the Sète and Grande-Motte meteorological stations of Météo France, and wave data (significant height, period and direction) were recorded every 30 min at the Datawell buoy located at a depth of 32 m off Sète (position: 3° 39 . 55′E, 43° 19 . 7′N) and at the Espiguette station situated at 4° 09 . 75′E, 43° 24 . 66′N (see locations in Fig. 1).

2.2 Numerical models

2.2.1 Coastal circulation model

The Boussinesq hydrostatic 3D circulation model SYMPHONIE (Marsaleix et al., 2006, 2008, 2009) was used to reproduce the circulation during the storm period. This model has been extensively used in studies of the Mediterranean Sea, mostly at the scale of continental shelves (Estournel et al., 2005; Herrmann et al., 2008; Reffray et al., 2004; Ulses et al., 2008b), generally comparing satisfactorily with available in-situ observations. Components of currents, temperature and salinity are computed on a C-grid using an energy-conserving finite-difference method. Vertical mixing is parameterized according to the k − ϵ turbulent closure scheme. A generalized sigma coordinate (Ulses et al., 2008b) is used in order to refine the resolution near the bottom and the surface. Recent developments in the SYMPHONIE model have integrated the wave-induced currents as described in Michaud et al. (2012). The wave-induced current theory follows the simplified equations of Bennis et al. (2011) based on the glm2z-RANS theory (Ardhuin et al., 2008b). These adiabatic equations are completed by additional parameterizations of wave breaking, wave streaming on the bottom and wave-enhanced vertical mixing.

The meteorological forcings (surface pressure, air temperature, relative humidity, wind velocity and radiative fluxes) are taken, every 3 h, from the Aladin model (a regional weather forecasting model by Météo France, focusing on France with a horizontal resolution of 10 km). A complete description of the bulk formulae used to compute the air/sea fluxes is given in Estournel et al. (2009). Daily river discharges were provided by Banque Hydro and Compagnie nationale du Rhône.

Three nested structured grids were deployed, which covered the north-western Mediterranean Sea (MEDOC) with a horizontal resolution of 2500 m, the Gulf of Lion (horizontal resolution of 800 m) and the Gulf of Aigues-Mortes (horizontal resolution of 500 m). The choice of the coverage and resolution of the finest grid was motivated by the need to represent the circulation in the zone studied by the research vessel Tethys II during the HYGAM cruises. All details concerning the different grids are given in Table 1 and Fig. 1. Twenty-one vertical levels were chosen for the GAM grid, and a generalized sigma coordinate (Ulses et al., 2008b) was used in order to refine the resolution near the bottom and the surface. The downscaling approach is detailed in Marsaleix et al. (2006). It was a combination of radiative conditions Flather (1976) and restoring conditions towards the solution of the parent grid, inside a sponge layer. The regional circulation model (MEDOC grid) was initialized and forced at the lateral boundaries by the large-scale Ocean General Circulation Model MFS (Tonani et al., 2008). Bathymetries from Berné et al. (2002) and from the LiDAR survey performed in 2008 for the nearshore were used. The bottom roughness length was set to 1 cm throughout the domain.

Computational grids used in the circulation model. imax and jmax are respectively the numbers of points in the west–east and south–north directions

| Grids | Resolution | Longitude | Latitude | i max | j max | levels |

| MEDOC | 2500 m | –0.39° E to 11.65° E | 38.39° N to 44.44° N | 402 | 270 | 40 |

| GoL | 800 m | 3.03° E to 5.75° E | 41.98° N to 43.57° N | 278 | 222 | 36 |

| GAM | 500 m | 3.5° E to 4.232° E | 43.15° N to 43.561° N | 120 | 93 | 21 |

2.2.2 Wave model

In order to take the effects of waves into account in the momentum equations, some quantities provided by wave models were required: period, significant wave height, direction, wavenumber, Stokes velocities, wavelength, the momentum flux from atmosphere to wave, and the momentum flux from wave to ocean in connection with wave breaking. Some of them could be directly provided by the wave model, and others calculated from the available parameters. The wave forcing was provided by the wave generation and propagation model WAVEWATCH III ® (Ardhuin et al., 2010; Tolman, 2008, 2009) (hereinafter WW3) version 4. This is a third generation wave-averaged model using an explicit scheme to solve the two-dimensional wave action balance equations for wave action density as a function of the wave direction and the wavenumber. The source/sink term in the action balance represents different physical processes: the atmospheric source function, the nonlinear quadruplet interactions and the dissipation by whitecapping. Other phenomena induced by the finite-depth effects like nonlinear triad wave–wave interactions, dissipation by bottom friction and dissipation by depth-induced breaking are taken into account. Thus, diffraction, reflection, refraction and shoaling are included. This model has been widely used at global and regional scales and validated using in-situ and remote sensing data (Ardhuin et al., 2008a, 2010; Delpey et al., 2010). Its validity is now extended to nearshore scales with the version 4 that includes parameterizations of wave breaking, bottom dissipation and wave dissipation (Ardhuin et al., 2010), and avoids the use of a specific nearshore wave model. We used the TEST405 parameterizations as described by Ardhuin et al. (2010), which are well suited to the younger seas that occur in the Mediterranean. As for the simulation of the circulation, the sea-state modelling also required three nested grids, the characteristics of which are described in Table 2. The areas covered by the wave grids were larger than those covered by the circulation grids for the needs of interpolation.

Computational grids used in this study: Nλ and Nθ are the numbers of points in longitude λ and latitude θ, and δt is the maximum global time step

| Grids | Resolution | Longitude | Latitude | Nλ | Nθ | δt (s) |

| WW3-MEDOC | 0.1° | –5.6° E to 16.3° E | 31° N to 45° N | 141 | 220 | 400 |

| WW3-GoL | 0.02° | 2.02° E to 11.86° E | 41.28° N to 44.45° N | 117 | 213 | 300 |

| WW3-GAM | 0.01° | 3.3° E to 4.5° E | 43.00° N to 43.70° N | 70 | 120 | 150 |

Simulations were run for the month of February 2007. The wind velocities were provided by the Aladin model every 3 h, except for WW3-MEDOC grid where Aladin was supplemented by Arpege (a global atmospheric model by Météo-France with a horizontal grid resolution of 15 km over France). Output wave spectra were discretized over 36 directions with 10° of resolution and 30 frequencies, fn, spaced with the relation fn+1 = 1.1fn from 0.05 Hz to 0.8 Hz.

One-way forcing was performed from the wave model to the circulation model: wave parameters were given to the GAM grid every hour, and to the GoL grid every 3 h. However, the wave forcing was not taken into account at the regional scale (MEDOC grid). It is possible that the feedback of current on waves might make a contribution, but this aspect was neglected and will be studied in future work.

3 Description of the measurements

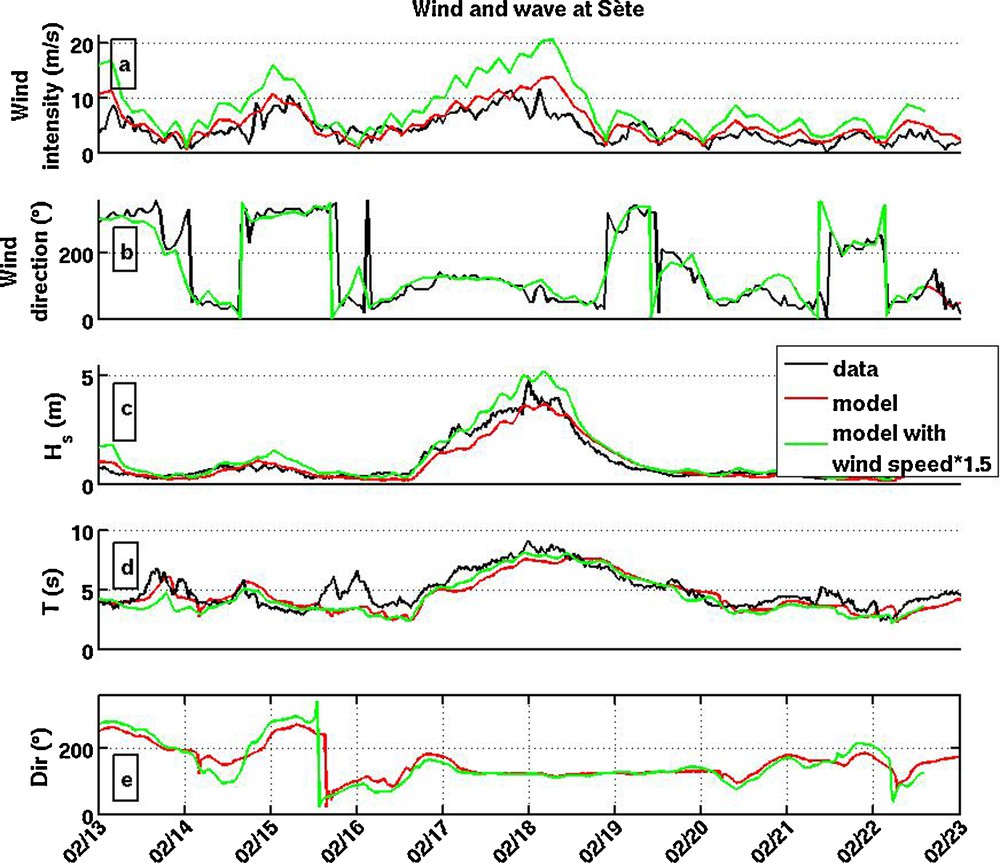

The BESSète station was moored for the first time on 12 February 2007, and recovered on 25 March 2007. This period of the year, at the end of winter, is characterized by omnipresent northerly winds, which blow mainly from the north-west (Tramontane) to the north-east (Mistral). These winds produce short waves of small amplitude. Most recorded currents were parallel to the isobaths (in the north-easterly or south-westerly directions) with intensities lower than 0.3 m . s−1, confirming the observations acquired through hull-mounted-ADCP surveys during the HYGAM cruises (Leredde et al., 2007). Leredde et al. (2007) also showed that this type of circulation could be very realistically reproduced by a numerical circulation model. These northerly winds act at the scale of the full continental shelf, thereby forming large eddies that persist for several days (Estournel et al., 2003). The additional interest of these data series is related to the storm that occurred on 18 February 2007. The local south-easterly winds measured at Sète remained moderate (10 to 15 m . s−1), but the waves generated over the general north-western sector of the Mediterranean reached significant wave heights greater than 5 m (Fig. 2). At the beginning of the storm, on the afternoon of 17 February, the current increased and was sheared in the surface layer. Between the bottom and –25 m, the current was depth-uniform, directed towards the south-west and flowing at 0.4 m . s−1. Then, from early on 18 February, the current strengthened in the entire water column, appearing almost depth-uniform. Its intensity reached 0.8 m . s−1 at the surface and 0.6 m . s−1 when averaged over the whole water column (Fig. 3) at the apex of the storm. It was oriented towards the west-south-west (200°). After midday, as soon as the wind and waves decreased, the current also decreased rapidly in the surface layer and at depth.

Wave and wind parameters during the storm and comparison in the atmospheric and wave models for the reference simulation (red), the simulation with the wind speed increased by a factor 1.5 (green) and in the observations (black) for: a: the wind speed (m . s−1); b: the wind direction (°); c: the significant wave height (m); d: the wave period (s) and; e: the wave direction (°).

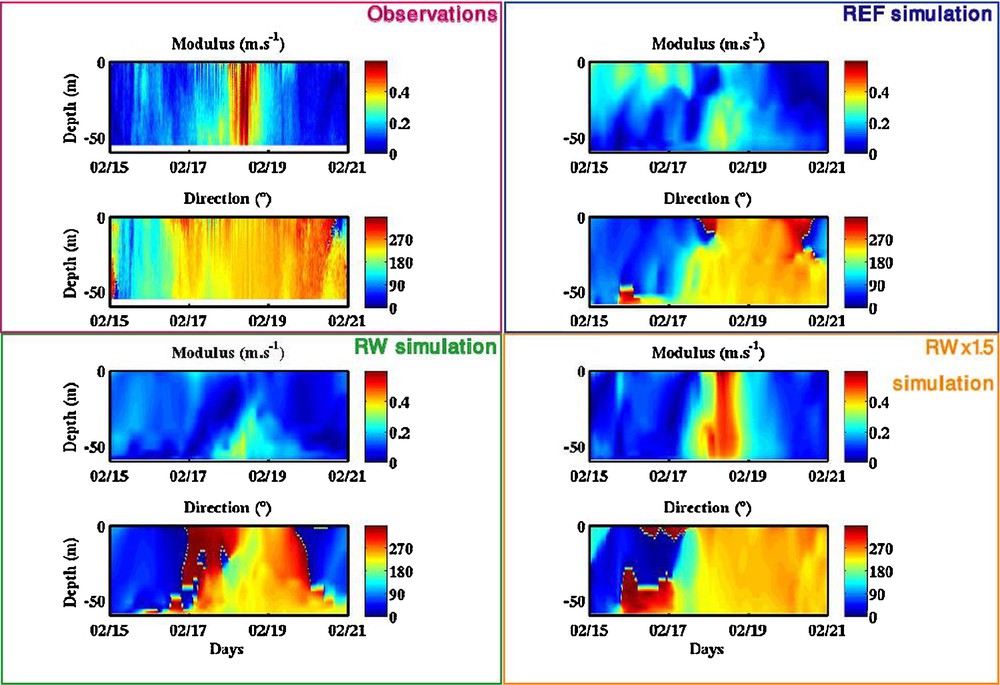

Time series of the vertical section of the current intensity for the observations (top left), REF simulation (top right), RW simulation (bottom left) and RW×1.5 (bottom right).

4 Comparison of model results with data

4.1 Reference simulation

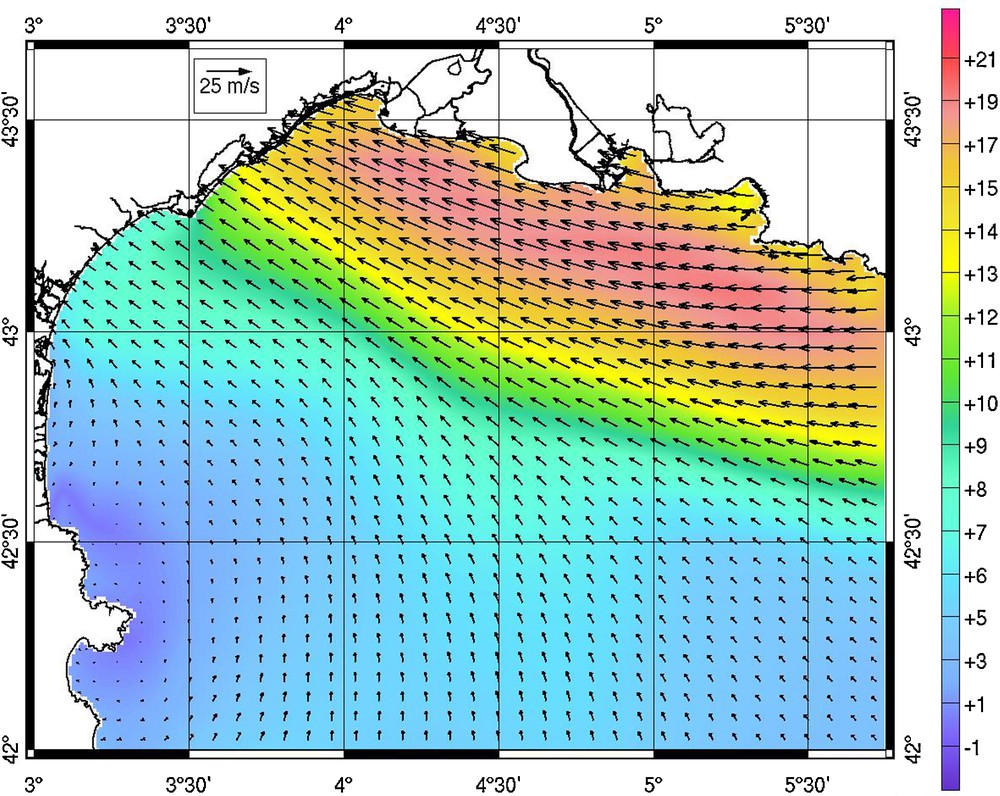

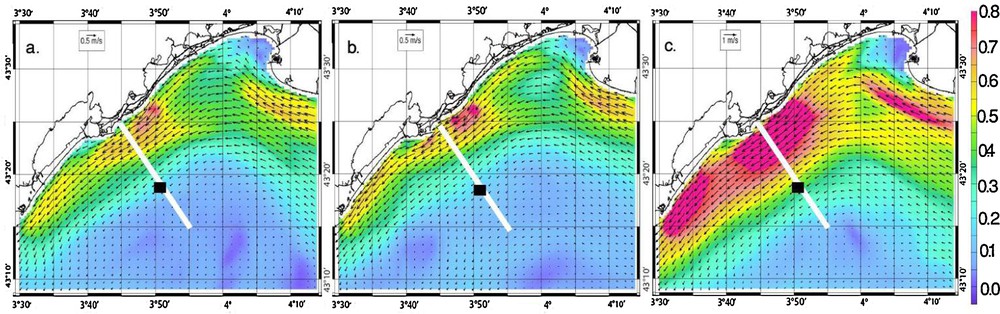

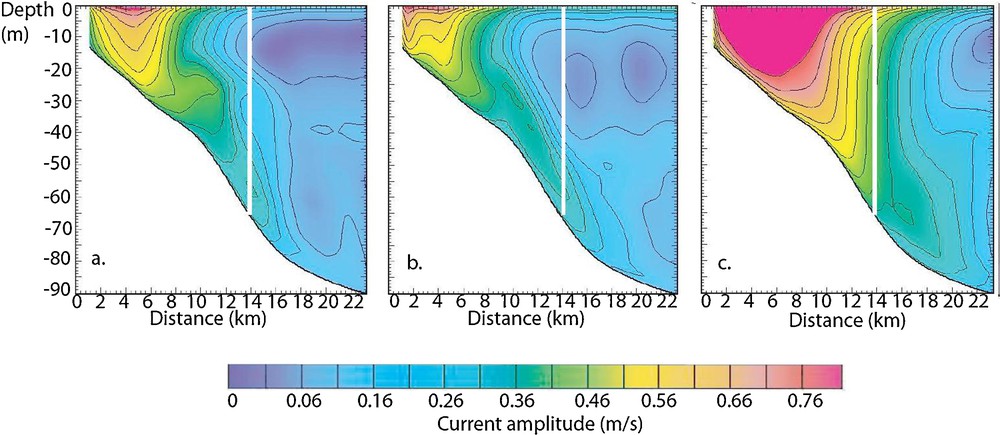

A first simulation was performed where atmospheric forcing and regional circulation (through the downscaling approach) were the only forcing applied. This simulation is called REF in the rest of the paper. The wave forcing was neglected in this case. The south-easterly wind observed at Sète was well reproduced in the Aladin model, with a peak at 13 m . s−1 at the storm apex (Fig. 2). The Aladin simulation showed that the south-easterly wind was strong throughout the North-East of the Gulf of Lion (Fig. 4). During the storm period, a strong coastal jet was generated towards the south-west (Figs. 5a and 6a). Current could reach intensities of the order of 0.9 m . s−1 close to the surface, and 0.46 m . s−1 near the bottom close to Sète and over isobaths shallower than 30 m. At the BESSète station, current was sheared in the surface layer with low intensities, and was more uniform near the bottom with values hardly reaching 0.3 m . s−1 (Fig. 3). Intensities were strongly underestimated compared to those observed. The direction of the current in the water column and near the bottom was well reproduced by the model, oriented towards the west-south-west. In the surface layer, the simulated current was oriented towards the north at the beginning of the storm, then turned towards the south-west in the afternoon of 18 February. In contrast with the observations, no depth-uniform current was simulated at the storm apex.

Wind speed (in m . s−1) and direction at the storm apex (at 8a.m. on 18 February) in the GoL.

Depth-integrated currents (in m . s−1) at the storm apex, in the REF simulation (a), the RW simulation (b) and the RW×1.5 simulation (c). The location of the ADCP is shown by a black rectangle and the white line corresponds to the vertical section shown in Fig. 6.

Vertical section of the current intensity for the REF simulation (a), the RW simulation (b) and the RW×1.5 simulation (c). The white line indicates the position of the BESSète station measurement and its location is indicated in Fig. 5.

A potential source of discrepancy may be attributed to missing processes linked to the high waves present at this period. In fact, there may have been a transfer of momentum from the waves towards the currents. These transfers are well known for the surf zone, where wave breaking can produce a longshore drift, for example. Lentz et al. (1999) have shown that this transfer can also occur in deeper waters. Very schematically, as soon as waves interact with the seafloor, i.e. as soon as waves have a wavelength (L) greater than twice the depth (D) (here, L > 150 m and D = 65 m), they are transformed (by refraction and dissipation) and may transfer momentum to the currents. This has already been observed at a depth of 30 m in the case of storms in the Bay of Banyuls (Denamiel, 2006; Michaud et al., 2012). A second simulation with the addition of the wave forcing (RW simulation) was performed to assess the wave effect at a significantly greater depth (65 m here).

4.2 Simulation with the wave forcing

The simulation of the sea state performed by WW3 gave a fairly good fit for the BESSète station data (not shown) and the wave-buoy data on the wave period and direction (Fig. 2 for the Sète wave buoy). However, the significant wave height and the period were underestimated respectively by 1 m and 1.5 s at the storm apex. The wave model identified strong wave heights growing in the north-east of the Gulf of Lion, where the wind speed was maximum, and then propagating towards the north-west in all the GAM. During the storm, a strong coastal jet directed towards the south-west appeared in the hydrodynamic simulation forced by waves. It extended less far from the shore than in the reference simulation, while currents were intensified in the nearshore zones (e.g., at Port-Camargue, Sète and in the Aresquiers shelf) (Figs. 5b and 6b). In fact, in these zones, waves interact with the bottom and transfer some momentum towards the current, making it stronger. When the simulated current was compared with those measured at the BESSète station, a strong underestimation of the simulated currents was observed (Fig. 3) in the simulated current. Currents appeared to be strongly sheared, reaching 0.15 m . s−1 at the surface and 0.3 m . s−1 close to the bottom in the rising stage of the storm. As in the reference simulation without waves, no strong, depth-uniform current was obtained at the storm apex, in contradiction with the observations. The difference between model and measurements, which was larger than that obtained with the REF simulation, mainly concerned the amplitude of the current, the current direction being rather similar in both cases. Waves exert a thrust on the sea surface that tends to push the water mass in their direction, and so to confine the coastal jet in the nearshore zone, making the current less strong beyond the 30-m isobath.

4.3 Sensitivity to the wind intensity

The previous section leads to the conclusion that the high waves associated with storms are able to significantly increase the current at depths smaller than 30 m, while beyond this region, their effects are small and even seem to induce a decrease of the current. As the strong observed current was limited to the period of the storm, the strong underestimation of the simulated current over the whole water column was probably due to an underestimation of the wind intensity or possibly of the wind event duration. The second hypothesis does not seem realistic when we consider the general agreement of the characteristics of the observed and simulated wind and wave time series at Sète (Fig. 2). On the other hand, the wind underestimation could be confirmed by the underestimation of the wave height and some authors have pointed out that the largest source of errors in a wave model is due to the wind (Ardhuin et al., 2007). More precisely, applying a wave model has been suggested to be an efficient way of assessing the quality of wind data (e.g., Bauer et al., 1992). It should also be noted that a decrease in the quality of atmospheric models near the coast has often been reported (Cavaleri and Bertotti, 2004; Michaud et al., 2012; Schaeffer et al., 2011).

We hypothesized that the narrow eastward wind structure (Fig. 4) could be poorly resolved by meteorological models, which would result in a smoothing of the local maximum. As the meteorological station of Sète is not located in this offshore wind structure, this hypothesis is not contradictory with the fact that the comparison between observation there and the Aladin model did not indicate such an underestimation. Finally, satellite wind data were examined to find evidence of this underestimation, but the absence of valid data near the coast did not allow any conclusion to be drawn. It was then decided to test sensitivity to the wind intensity. As the meteorological situation was spatially and temporally complex, the objective was not to determine the wind intensity through an adjustment of the simulated current to the observation. We rather hoped to understand how current is sensitive to wind intensity in coastal regions where the wind effects are more complex than in the open ocean.

A numerical simulation was carried out, similar to the previous one but with a simple increase in the wind by a factor 1.5 in the circulation and wave models at the Gulf of Aigues-Mortes scale (RW×1.5 simulation). The simulated wave heights at Sète were now globally overestimated (Fig. 2), indicating that our approach was obviously too simple. In fact, despite the fact that both are based on the wind forcing, the generation of currents and the generation of waves in the context of large fetches do not take place at the same spatial scales, since waves integrate the effect of wind over long distances, whereas the generation of currents is a more local process or, at least, is less dependent on upstream conditions. The hydrodynamic simulation produced a stronger and larger coastal jet (Fig. 5c) than in the REF simulation. At the BESSète station, currents were very similar to the observations. In the rising stage of the storm, they were sheared in the surface layer and depth-uniform below, with intensities increasing continuously to reach, at the apex, 0.6 m . s−1 near the sea surface and 0.42 m . s−1 near the bottom (Fig. 3), with a fairly depth-uniform profile and a constant direction in the entire water column, similar to the observations. Then, after the apex, the current decreased rapidly everywhere. So this simulation confirmed that the current at the BESSète station was highly sensitive to the wind forcing.

5 Analysis and discussions

The main result of this study concerns the necessity to enhance the wind forcing of the numerical model to reproduce the strong currents recorded during the storm. The mechanisms responsible for such strong currents are now examined. The use of a sophisticated 3D model taking various non-linear processes into account is not appropriate for this analysis. Thus, we return to the theory to analyse the two dominant wind-induced processes: first, the solution known as the Ekman spiral which is valid in the absence of coast and second, the simplified case of the longshore wind that results in a barotropic geostrophic current (Csanady, 1982). These two processes act together, and current is the sum of the two solutions:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

The coefficient of vertical diffusion is given by:

| (6) |

This theory is valid far from any boundaries; the water column must be supposed sufficiently deep for bottom stress to be negligible. The motion must be forced by the wind stress and any transient must have decayed, leaving only steady flow. At the BESSète station, the water depth is 65 m, so the bottom stress can be considered of second order.

Under a constant wind blowing in the direction −x (alongshore to a coast) with a stress equal to , the geostrophic current is given by:

| (7) |

| (8) |

Before tackling the analysis, we need to define the wind speed chosen for the theoretical calculations in the rising stage and the apex of the storm. In the rising stage of the storm (at 10 p.m. on 17 February for example), the wind speed is equal to Vcoast = 13 m . s−1 at the meteorological station. At the storm apex (at 8 a.m. on 18 February), 13 m . s−1 (= Vcoast) is also recorded at the meteorological station. However, since we suspect a wind underestimation, we will study two values of wind at the BESSète station: 1/the same value Vadcp = Vcoast and 2/ Vadcp+ = 1.5 × Vcoast. The results obtained theoretically will provide additional clues to confirm or clarify our theories.

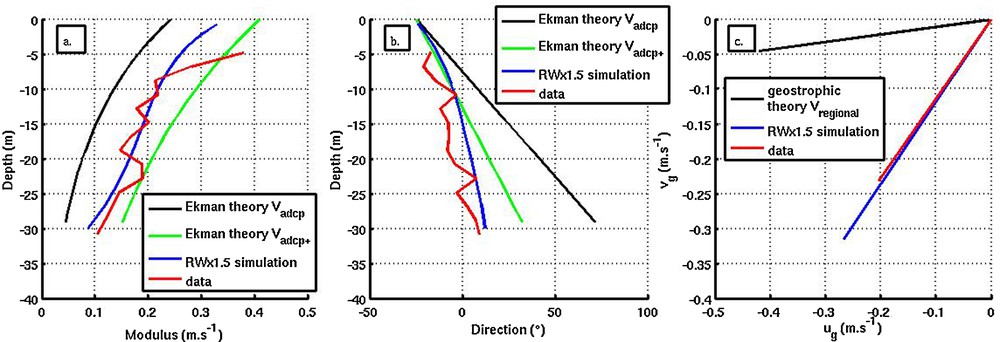

5.1 In the rising stage of the storm

We noticed that, in the rising stage of the storm (for example at 10 p.m. on 17 February), the observed current was sheared in the surface layer. To check whether the current was the sum of an Ekman current and a geostrophic current, the barotropic geostrophic current was estimated and, then substracted from the total current in both the observation and simulation to check if the remaining current was similar to an Ekman spiral. The forcing conditions during the storm increased since 16 February, two Coriolis periods have elapsed, so we can consider that an important part of the transient motion has decreased. The barotropic geostrophic current was estimated from the average of the current between 30 m and 60 m below the surface. Once it had been removed from the current profile, the current in the surface layer looked like an Ekman spiral (Fig. 7a and b), decreasing with depth and rotating on its right. To go further in this analysis, the theoretical vertical profile of the Ekman current was calculated following Eq. 4 according to the wind stress, itself calculated from the wind intensity through the non-linear bulk formulae described in Estournel et al. (2009). Using the value of Vadcp at this moment (i.e. the wind measured at the meteorological station), or this value multiplied by 1.5 (Vadcp+), resulted in an increase of the wind stress τ by a factor 2.9 (τ =0.3 and 0.86 N . m−2 for the two cases). The theoretical vertical Ekman profiles of current were then superimposed on the ‘observed’ and ‘simulated’ currents in Fig. 7. The rotation of currents was very similar for the four profiles. Simulated and observed currents were between the theoretical currents calculated with wind velocities Vadcp and Vadcp+. We can thus suppose that the wind speed was between these two values at the BESSète station at this time.

Comparison of the observed and simulated current during the rising stage of the storm (at 10 p.m. on 17 February) to the theoretical current. a. and b.: Comparison of the vertical profiles of the observed (red) and simulated (blue) currents (RW×1.5 simulation), to the theoretical profiles of the Ekman spiral induced by two wind of intensities equal to Vadcp = 13 m . s−1 (black) and Vadcp+ = 19.5 m . s−1 (green). a: top view and b: profile view. c: Comparison of the simulated (blue) and observed (red) current averaged between 30 m and 60 m below the surface to the theoretical barotropic current associated with a wind blowing at Vregional = 13 m . s−1 (black) towards the west direction, calculated according to Eq. 8.

Now let us come back to the simulated and observed barotopic geostrophic current, estimated below the surface layer. Their values at 10 p.m. on 17 February were equal to 0.41 m . s−1 and 0.3 m . s−1, respectively, and they were directed towards the south-west (Fig. 7c). To check whether these values were of the same order of magnitude as the theoretical values of Eq. 8, several simplifications had to be made to specify the parameters used in this relation. While the Ekman current is induced by the local wind (here at the BESSète station), the geostrophic coastal jet probably depends on the wind on a larger scale. In particular, the wind blowing along the coast is expected to have an effect on the sea surface slope. In order to calculate the geostrophic current through Eq. 8, we considered the wind averaged over the region extending from the coast to the BESSète station (westward wind of velocity Vregional = 13m . s−1). From the wind time series, we specified that at 10 p.m. on 17 February, the wind had been blowing for 26 h. The distance between the BESSète station and the coast is far smaller than the barotropic Rossby radius (y << R). With these simplifications, the theoretical geostrophic current was directed towards the west-south-west direction (260°), with an intensity similar to that of the observations (0.43 m . s−1). The main limitation of the theory for our case was the local complexity of the coast. The wind was approximately parallel to the coastline located upstream of the BESSète station, but not parallel to the coast nearest to the BESSète station (see Figs. 1 and 4). The comparison between the theoretical current on the one hand and the observed and simulated values on the other one could indicate that the current direction at the BESSète station was imposed by the direction of the local coastline, while its intensity was rather explained by the fact that the coastal jet was established upstream where the wind was parallel to the coastline.

To conclude this section, the current during the rising stage of the storm is as in the theory, the sum of the Ekman solution and the geostrophic solution. The surface shear is induced by the action of wind via the Ekman spiral and the strong current at depth is induced by the sea surface slope. Let us now examine the case of the depth-uniform current at the storm apex.

5.2 At the storm apex

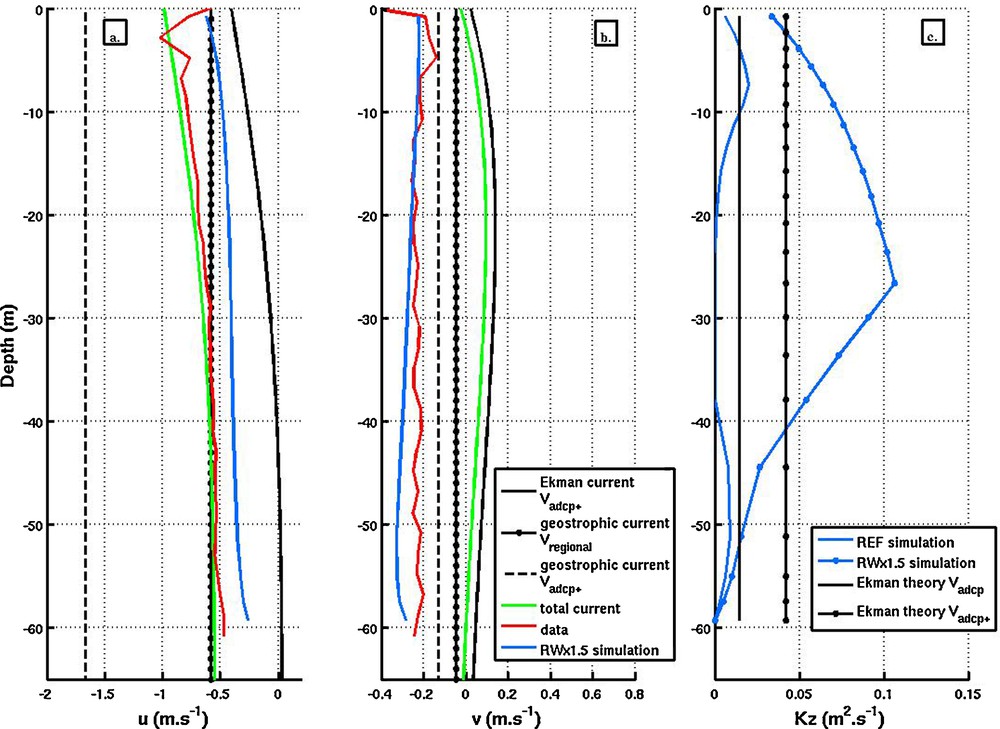

At the storm apex (at 8 a.m. on 18 February), an intense current was observed, less sheared than before and reproduced only in the RW×1.5 simulation. The theoretical geostrophic current was calculated from Eq. 8 for a wind blowing from the east for 36 h with a speed of Vregional = 13 m . s−1 and Vadcp+. The vertical Ekman spiral was also calculated with the local wind of velocity Vadcp+ blowing from the east-south-east (110°). The (constant) geostrophic and Ekman currents are presented in Fig. 8 along with the observed and simulated currents.

Comparison of the vertical profiles of the observed (red) and simulated (blue) currents (component u in a. and in b.), to the theoretical vertical profile of the Ekman current induced by a wind of Vadcp+ = 19.5 m . s−1 (black) and to the theoretical vertical profile of the barotropic geostrophic current for a wind of Vregional = 13 m . s−1 (dashed dotted black) and Vadcp+ = 19.5 m . s−1 (dashed black) on February 18 at 8 a.m. during the storm apex. In green, the total current that is the sum of the Ekman current and the barotropic geostrophic current. In c: Comparison of the vertical profile of the coefficient of vertical diffusion Kz simulated (blue) to the theoretical ones (black) calculated from Eq. 6 for the wind velocities Vadcp and Vadcp+.

The Ekman current is more depth-uniform at this stage than during the rising stage (Figs. 7 and 8). Due to the wind strengthening, the Ekman surface layer D (calculated from Eq. 5) is thicker and the vertical mixing Kz (calculated from Eq. 6) is increased (Fig. 8c). As in the case of the rising stage of the storm, the Ekman current alone cannot explain the strong current recorded. Also, the total current (in green in Fig. 8) resulting from the addition of the Ekman current and the geostrophic current calculated with a wind of velocity equal to Vregional are very similar to the observations and the simulation. (This is particularly true for the x-component.) Moreover, the continuous increase of the current over the duration of the storm (about 36 h) is predicted by the theory (Eq. 8).

In conclusion, increasing the wind intensity has two consequences: first the current is increased over the whole water column, and second, the vertical mixing is also increased, resulting in a more homogeneous vertical current profile.

5.3 After the storm apex

As soon as the wind decreased, the current decreased rapidly in the surface layer as the source of momentum at the surface also decreased. More surprisingly, the current at depth also decreased rapidly, despite its geostrophically balanced nature. This behaviour, which is not in agreement with the simple theory used above, but is rather well reproduced by the model, was probably due to the bottom friction and to 3D effects.

6 Conclusions

The current vertical profile was observed at 65 m depth during a typical winter onshore storm. Strong currents were recorded with velocity reaching 0.8 m . s−1 close to the surface and 0.5 m . s−1 near the bottom. A 3D hydrodynamic model was applied to estimate its potential to reproduce extreme currents. The simulated current was strongly underestimated compared to the observations. A sensitivity test was carried out to determine if this underestimation could be induced by the presence of high waves. As this hypothesis did not seem sufficient, another test was done with the wind increased by a factor of 1.5. A crude increase by this factor allowed the observed current to be reproduced. Unfortunately, neither in-situ nor remotely sensed observations of wind were available in the strong wind vein to enable our hypothesis of underestimation of wind stress to be evaluated. However, although the factor 1.5 that was applied to the wind from the meteorological model seems strong, it must be realized that an underestimation of wind stress could also be due to other factors such as the presence of strong wind gusts during the storm and the underestimation of the drag coefficient induced by a complex sea state. However, for the second hypothesis, if the surface drag coefficient is increased, then the wind speed will be decreased, and so the current. These processes must be studied more seriously in order to understand which one will prevail over the other.

A theoretical and simplified analysis isolated the wind-induced processes responsible for the strong currents measured during the apex and the strong vertical shear at the beginning of the storm. These processes were the barotropic geostrophic current induced by the wind parallel to the coast and the Ekman spiral. The duration of the storm (about 36 h) explains the continuous increase of transport during this period, as predicted by the theory. The frictionally induced Ekman transport explains the current shear in the surface layer in the rising stage of the storm, and the addition of high waves and strong wind at the apex is more in favour of strong vertical mixing in the surface layer.

We are aware that this study and the hypotheses are based on a single series of measurements at only one location and for only one storm. However, in Michaud et al. (2012), a similar case of strong current recorded at 28 and 30 m of water depth and underestimated in the simulation was studied in the Têt inner shelf (along the Roussillon coast) during the storm of February 2004. By increasing the wind speed by a factor of 1.2, the simulation was improved and agreed with the observations. These two studies both concluded on the weakness of circulation and atmospheric models during storm periods. A data set including current profiles, wind measurement at several coastal sites, and tide gauges estimating the set-up would be necessary to progress on this question.

A correct simulation of strong currents is actually crucial in coastal models, especially for sediment transport purposes. This problem is all the more important at depths larger than ∼40 m, where wave-induced bottom friction is insufficient to induce sediment resuspension, while strong currents induced by storms are expected to generate such resuspension (Ulses et al., 2008a). Additionally, because of their intense vertical shear, these currents induce vertical mixing, which spreads the suspended matter through the whole water column. Finally, via these two processes, strong currents determine the amount of matter resuspended, its residence time in the water column and the distance over which the matter can be transported. A bottom current of 0.4 or 0.5 m . s−1, as recorded in our case, induces a bottom stress which is 1.8 to 2.8 times the one obtained (on the basis of the bulk formulae of our model) with a current of 0.3 m . s−1 as present in the reference simulation. Such a difference can be crucial for the switch from a situation without resuspension to a situation with resuspension generalized over huge areas.

Acknowledgements

We warmly thank Cyril Nguyen and the POC crew for their assistance. We acknowledge Météo France for the ALADIN and ARPEGE for the model outputs, Fabrice Ardhuin for his help with the WW3 model, Simon Fresnay for his expertise concerning the satellite images and Susan Becker for her proofreading. We thank the DREAL of Languedoc-Roussillon for the LiDAR bathymetry and MOON (the Mediterranean operational oceanography network) for OGCM outputs. Héloïse Michaud was financially supported by the CNRS and the Languedoc-Roussillon Region. The SYMPHONIE ocean model is developed by the SIROCCO group. Sources are available at http://sirocco.omp.obs-mip.fr/outils/SYMPHONIE/Sources/SYMPHONIESource.htm. We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions on the manuscript.