1 Introduction

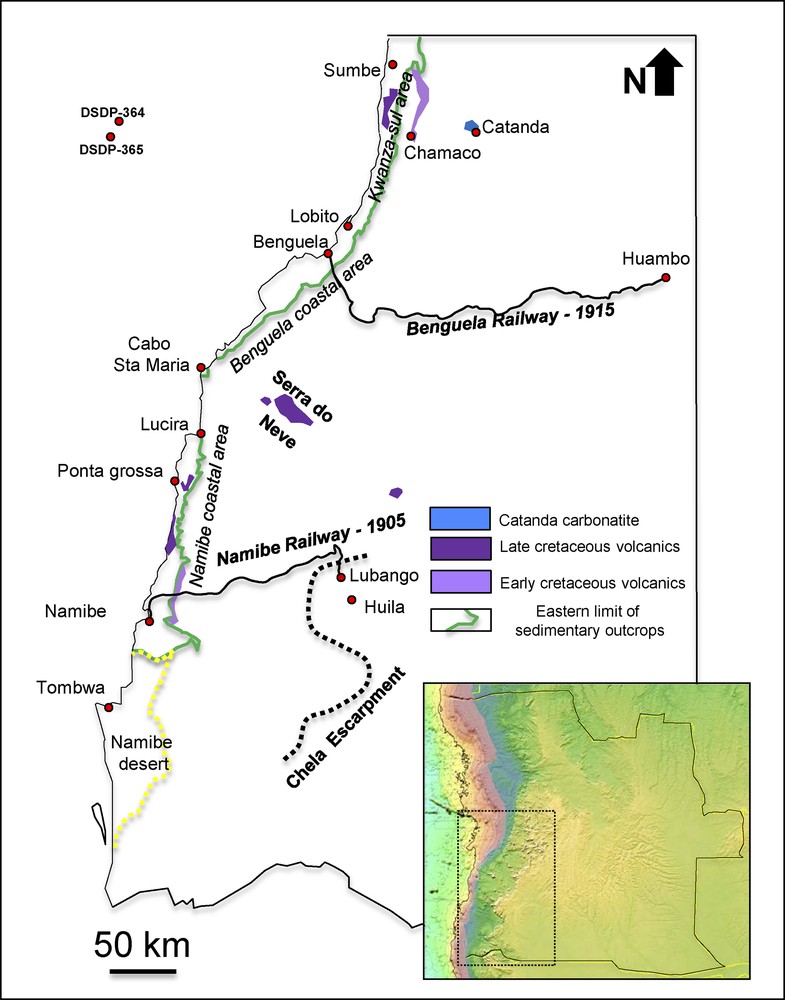

This paper, based on already published books or articles, is intended to introduce the readers to the geological discovery of the coast of Angola, from Sumbe to Namibe (Fig. 1), and to show the evolution of geological knowledge over time. Papers published in the 19th century as in the colonial period when Angola was one of the Portuguese colonies in Africa up to 1974 are difficult to find, especially online. We thus made a special effort to collect them as extensively as possible.

(Color online). SW Angola simplified geological map, with main Cretaceous volcanics and coastal sedimentary outcrops. The locations are mentioned in the text

2 The early geological exploration of Angola

Explorers of Angola during the XIXth century were adventurers, like Laszlo Magyar (1818–1864), who explored Angola between 1849 and 1857–he was sufficiently instructed to make general scientific observations of the country (i.e. its inhabitants, fauna, flora and rocks), provincial governors, such as Fernando Costa Leal (1825–1869) who wrote a report of the journey he made in 1854 throughout the Cunene region, and naturalists. Sometimes, the expeditions were supported by Portuguese governments: D. Maria II recruited the Austrian botanist Friedrich Welwitsch (1806–1872) (in Morelet, 1868), who travelled through Angola between 1853 and 1860, describing the African shield and its sedimentary cover. When attempting to make stratigraphic attributions to the Kwanza sedimentary series, he made some errors by relating Angola's stratigraphy to European geology, but still, he was the first to give a reliable description of the Mesozoic strata succession.

John Joachim Monteiro (?–1878), a mining engineer educated in London at the newly created Royal School of Mines, travelled through Angola in 1853 and 1864. He was working for the Bembe Copper Mines, in the North of Angola, but he also visited the western part of the country up to Mossamedes (Namibe now) to make an inventory of its mineral resources. An extensive colonization along the coast between Lucira and Namibe by settlers arrived from Brazil in 1849 probably helped him to explore the region: there, he discovered basalt traps reaching the sea, a gypsum formation, and the volcanic rocks that underlie the latter near Namibe (Fig. 2).

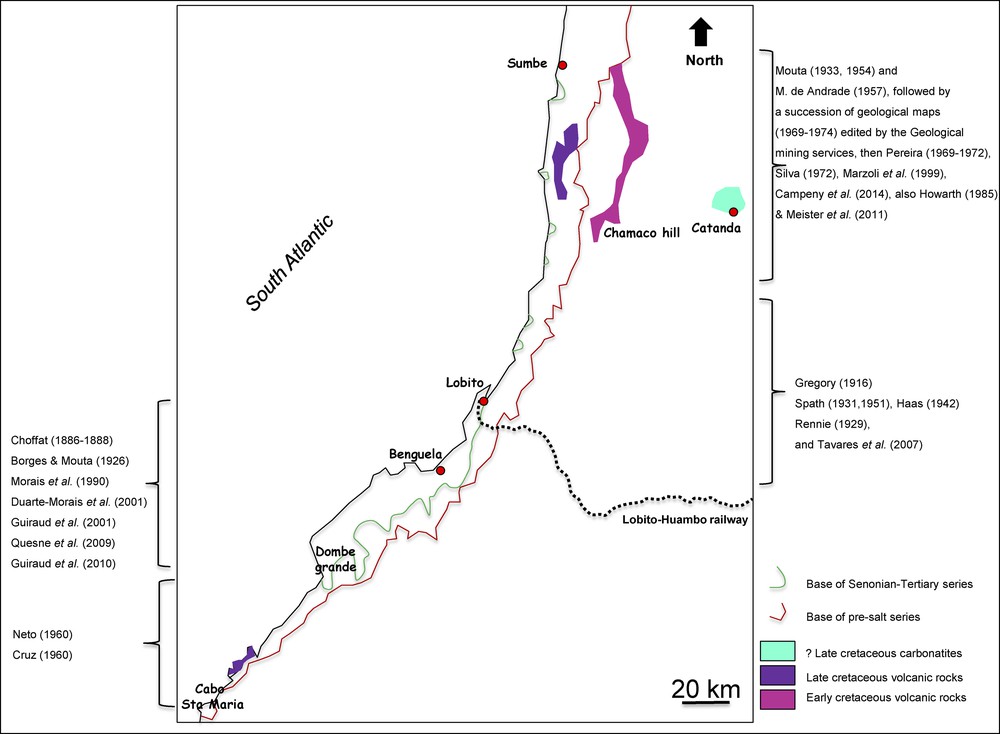

(Color online). From Sumbe to Cabo Santa Maria: main Cretaceous volcanics and coastal sedimentary outcrops of the Benguela coastal area. The locations and the main related publications are mentioned in the text.

Funding from the Geographical Society of Lisbon in November 1875 enabled several expeditions to reach South-West Angola. In July 1876, Hermann Von Barth (1845–1876), a German mountaineer and scientific explorer, led a campaign in the Kwanza region, which unfortunately ended abruptly due to exposure to tropical diseases. In the wake of this failure, Von Barth committed suicide in Luanda in December 1876 and all the materials collected during the expedition were lost. From 1877 to 1884, Portugal conducted other campaigns to promote its “historical rights” over African territories (Diogo & Amaral, 2012): two expeditions were set up by Hermenegildo Capello (1841–1917) and Roberto Ivens (1850–1898) in Kwanza, and by Alexandre de Serpa Pinto (1846–1900) in Huila. A third expedition was conducted by the first two officers, in 1883–1884, in Huila. All these expeditions yielded limited scientific results, at least on geology (Capello & Ivens, 1881, 1886). A strong debate confronting partisans of publicly exposed trans-Africa expeditions, mainly members of the Society of Geography of Lisbon, and those who advocated discrete but more efficient fieldwork, the Cartography Committee and the Minister of Overseas Territories (Madeira Santos, 1986), took place at that time.

Simultaneous, another mining engineer, Lourenço Antonio Pereira Malheiro (1842–1900), travelled to the Benguela region in 1882 in search of potential ore deposits (copper, coal, gypsum, sulfur) (Choffat, 1888). Malheiro's expedition produced a rich collection of fossils from the Benguela–Lobito region. This collection was shipped rapidly to Paul Choffat (1849–1919), a Swiss geologist who worked for the Portuguese Geological Survey, leading to the first studies of the Angola Albian formations. Choffat was aware of the geological interest of Angola (Carneiro et al., 2014), especially since the discovery of Albian ammonites in West Africa (Elobey island–Equatorial Guinea, but also Lobito and Namibe areas) by Oskar Lenz (1848–1925) during the German Loango oceanographic campaign led in 1873–1876 along the West Africa shoreline (Lenz, 1882). The first paper published by Choffat on the specimens sent by Malheiro dates back to 1886; it was published in the Portuguese journal Boletim de Sociedade de geografia de Lisboa. However, for greater international outreach, it was also published in German, French and Swiss journals, in 1887 and 1888 (Choffat, 1987a, b, 1988). Additional papers were coauthored by Perceval De Loriol (1828–1908), a Swiss paleontologist specialist on fossil urchins. Even if Choffat's papers lack information on the geological context of the collections, which was insufficiently documented by Malheiro, they are considered a seminal work regarding the geological and paleontological knowledge of the Albian in the Benguela-Lobito area.

With the exception of a late publication on Angolan coastal geology by Choffat in 1905, geological activity in the Benguela–Namibe regions remained moderate until the end of the Portuguese Monarchy, in 1910. General geological observations were made by Carl Höpfner (1857–1900), a German geologist who mentioned in 1883 the traps cropping out all along the coast between Namibe and Lucira. Höpfner visited also the oil-seep (“fontes de petroleo”) for which one settler had obtained a concession. In the Namibe coast and its hinterland, J. Pereira do Nascimento (1898–?) promoted the colonization of the area in a new journal first published in 1894: Portugal em Africa, Revista cientifica. Riding on a camel during a field trip that lasted several months, between 1894 and 1895, Pereira do Nascimento described the sites of copper mining in the basement and mentioned a bitumen outcrop along the coast, amongst several other observations (Fig. 3).

(Color online). From Cabo Santa Maria to Namibe: main Cretaceous volcanics and coastal sedimentary outcrops of the Namibe coastal area. The locations and the main related publications are mentioned in the text.

3 Geological exploration of Angola during the first half of the 20th century

At the beginning of the Portuguese First Republic, a new impulse was given to the geological exploration of Angola with the arrival of José Norton de Matos (1867–1955) as the governor of the colony (1912–1915, 1921–1924). Angola was proposed to colonization to Portuguese migrants, but also to Jews and Italians. At that time, oil-companies were also welcomed (USA Sinclair), especially in the Kwanza region. Journals with more or less scientific purposes were created: Cadernos Coloniais (first volume published in 1920), Boletim Geral das Colónias (first volume in 1925). Several works by José Bacelar Bebiano (1894–1967) (Head of the Geological Survey of Angola between 1916–1922, and Minister of Overseas Territories for a while, in 1928), and Fernando Mouta (1898–?) were published in those journals. For the first time also, the geology of Angola was introduced in the International Geological Congresses: first, in the Liège session, in 1922, by Ernest Fleury (1878–1958); then in Madrid (1925), Pretoria (1929) and Washington (1933). F. Mouta presented in Pretoria (1929) an update of the geological map of the colony initially published by Bebiano in 1926.

A turning point in the discovery of the geology of South-West Angola was the construction of the Benguela railway between 1903 and 1929. It facilitated scientific expeditions, as the one led by J. W. Gregory (1864–1932), a well-known British geologist. He went to Angola in 1915 with the approval of the Portuguese government, to find settlement places for Jews, at the request of the Jews Territorial Organization. In 1916, Gregory published a paper with a sketch of a geological map based on his observations along the railway up to Huambo. He noted the existence of volcanic rocks and suggested that they might be a testimony of formations younger than the basement. Several publications followed on the petrography of these volcanic rocks and on fossils Gregory collected (Spath, 1931; Tyrell, 1916). At the same time, Arthur Holmes (1890–1965) published observations on the petrography of igneous samples from the prior collections of Malheiro and Monteiro, collected between Benguela and Namibe. Holmes then emphasized the importance of alkaline igneous rocks (Holmes, 1916). In the Namibe region, the geological discovery of the hinterland was made by two mining engineers: Francisco Pereira de Sousa (1870–1931), who published the first geological map of South-West Angola (1915) and observations on volcanic rocks (de Sousa, 1916), and Bacelar Bebiano, who wrote several papers on the mineral resources of the region (Bebiano, 1926). The lack of good topographic maps precluded the production of a detailed geological mapping.

The Benguela–Lobito area was investigated further by the Vernay campaign (1925), which led to the collecting of fossils in the Benguela area, which were sent to the New York Museum of Natural History, and further studied by Otto Haas (1942a, b). Haas’ work and the one by Rennie (1929) revealed the existence of a fauna of Campanian–Maastrichtian age, north of Lobito, distinct from the Albian fauna previously described.

In the same period (1921–1925), the Portuguese republican government launched a geological expedition: the Missão Geologica de Angola (Brandão, 2008). In the meantime, topographic surveys were also launched (1921–1924). The members of the expeditions produced only few publications, but conducted extensive geological fieldwork in numerous parts of the country. Their main production was a paper on the Benguela area (Mouta & Borges, 1926) and an updated geological map of the country (after the one published by Bebiano). The Missão had also the aim to create a geological institute in Angola (Guedes, 1931). The paleontological specimens collected by the Missão were sent to Leonard F. Spath (1882–1957), who published part of his work (Spath, 1931). In the geological map by Mouta (1936), Albian formations were broadly identified, with their volcanic intercalations along the coast, between Lobito and Sumbe.

Concerning the Namibe region, it was only sporadically explored: Raoul Dartevelle (1907–1956), a Belgian geologist, published some paleontological observations (Dartevelle, 1942). The lava flows and volcanoes of the coastal area north of Namibe were included in the 1933 map of Mouta. The 1930s marked the beginning of the study of Angolan landscapes, especially Serra de Chela in South-West Angola. A German geographer, Otto Jessen (1891–1951), analyzed the superimposition of erosion surfaces between the Namibe coastal area and the Lubango plateau (Jessen, 1936).

4 Geological studies in Angola between 1949 and 1975

In 1941, the Portuguese government launched an exhaustive topographic mapping of Angola (Santos, 2006), first in the field, and later from the analysis of aerial pictures (late 1950s). Those topographic maps will form the basis for the geological mapping of the coastal area between Sumbe and Benguela. In 1964, a 2:2 million scale coastal map of the basins was published, underlining the progress made in the country's geological knowledge (Neto, 1970). The final product resulting from all geological activities until 1974 was the 1:1 million scale geological map of Angola, published by the National Laboratory of Tropical Scientific Research of Portugal in 1982. This map was a masterly update of the Mouta's geological maps of 1933 and 1954.

South of the Kwanza basin, which had been mapped by geologists of oil companies since 1952, the geological cartography was done by geologists of the Geological Mining Services: from Benguela to Cabo Santa Maria, by Mascarenhas Neto (between 1956 and 1961), and from Lobito to Sumbe, with the publication of a set of geological maps at the scale 1/100,000 and associated memories, between 1970 and 1972. Two sets of volcanic outcrops were described (Pereira, 1969, 1971) and dated as Early Cretaceous inland and Late Cretaceous along the coast (Torquato and Amaral, 1973). Further inland, Silva and Pereira (1972) described the Catanda carbonatites for the first time. Lapido-Loureiro (1926–2012) made an inventory of carbonatitic and alkaline complexes (Lapido-Loureiro, 1967). Coastal mining geology was also considered: Van Eden (1978) showed that copper-rich gossans were found all along the Sumbe–Benguela coast in presalt deposits. In the coastal area, Rennie (1945) and Spath (1951) confirmed the existence of Campanian–Maastrichtian series by analyzing Mollusk and Globotruncanid assemblages. Cooper (1973) described an assemblage of Cenomanian ammonites near Sumbe.

The Namibe coastal sedimentary series were studied by G. Soares de Carvalho (1961), who published a regional synthesis. Besides his 1/40,000 map, he provided detailed discussions on each formation, dating problems, mineral occurrences, etc. Later on, the same author discussed the interpretation of presalt sedimentary cartography and the possible occurrence of paleovalleys in the basement filled by presalt sedimentary series (Soares de Carvalho, 1968, see also discussion in Feio, 1981). He also analyzed the geometrical relationships of those paleovalleys with mineral occurrences (iron, manganese, barite) in presalt silicified carbonates. Clarification about the Cenomanian–Turonian age of Ammonites assemblages at Punta Negra was provided by Howarth (1965, 1966) and Cooper (1972). Contrary to the Sumbe-Benguela coast, Coniacian and Santonian deposits were found preserved in the Namibe region (Fig. 2). Senonian and Paleogene series and their paleontological content were described by Antunes Telles (1964).

Thus, most geological fieldwork was done by members of the Geological Survey of Angola: Heitor De Carvalho, Mascarenhas Neto, G. Soares de Carvalho, Antonio Graça da Cruz, Alexandre Borges. Detailed petrographic analyses were made by Portuguese Universities (Coimbra, mainly, but also Lisbon and Porto), but some of them were done in Luanda at the Institute de Investigação cientifica de Angola. Volcanic rocks and basement petrography were discussed in detail by Miguel Montenegro de Andrade (1919–2012) from 1950 to 1966, with a particular interest for the alkaline series of Kwanza and Namibe. Absolute dating of igneous rocks was accomplished by the French University of Clermont-Ferrand in the 1960s (Mendès, 1964), then by the Brazilian University of Sao Paulo (Torquato & Amaral, 1973).

Journals, Bulletins, and Memories containing geological papers were published in the African colonies of Portugal during those years, among them Boletim dos Services Geológicos e Mineiros de Angola (first volume in 1950), Garcia de Orta, Memórias da Junta Investigações Cientificas do Ultramar, Boletim do Instituto de Investigação Científic de. Angola (first issue in 1962), Ciências Geológicas da Universidade de Luanda. Portuguese geologists coming from Angola participated in the sessions of the International Geological Congress from 1948 to 1972, but the work of M. Neto, G. Soares de Carvalho and E. Pereira was never prized by the international geological community, contrary to the work of Mouta, which was acknowledged in the 1930s (Mouta, 1930).

Offshore Angola, oceanographic programs promoted by the Academia were put forward: during the 1960s and 1970s, several campaigns were performed on the vessels of the Woods Hole Institute, with the purpose of acquiring gravimagnetic and seismic reflections data (Uchupi & Emery, 1972). Geophysicists like Francheteau & Le Pichon (1972), Emery et al. (1975), Cande & M. Rabinowitz (1978), made the first interpretations of the main features of the Angola margin: magnetic anomalies, transform faults, salt thickness and diapirs. DSDP (IPOD) Leg 40 international campaign, conducted between the end of 1974 and the beginning of 1975, drilled two wells offshore (DSDP 364/365), the first offshore wells in the Kwanza basin. They allowed one to get a full set of modern and new data based on an almost continuous coring from Late Aptian to Eocene. A DSDP volume based on this information was published in 1978. One year later, the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) was extended to 200 km offshore, and the first offshore Kwanza oil-exploration wells were drilled (1981–1983).

5 The geological knowledge of Angola after the country's independence

During the decades that followed the independence of Angola, the geology of the South-Kwanza, Benguela and Namibe regions was mainly analyzed on three lines.

The Portuguese, Brazilian, French and South-African academic geologists that were already working in the country continued to work and publish, using mainly collections and observations they had made years before, as geological fieldwork had become almost impossible due to the Angolan civil war. Torquato (1977) provided a synthesis of the available absolute dating. Pereira & Moreira (1977) published a map of the region south of Benguela, whereas volcanic rocks of the Serra de Neve mountain and other Cretaceous volcanic complexes were studied by Alsopp & Hardgraves (1985), Issa-Filho et al. (1992), Alberti et al. (1992, 1999), Renne et al. (1996) and Marzoli et al. (1999). The Quaternary history of coastal uplift was studied by G. Kouyoumountzakis & P. Giresse (1976), then by Giresse et al. (1984), with the help of carbon dating of biogenic materials. Near Sumbe, Howarth (1985) recognized a Cenomanian–Turonian assemblage of Ammonites. In the Namibe basin, Cooper made a synthesis of the stratigraphy of the Cretaceous succession, based on Ammonites and field observations (1978–2003): Cenomanian to Santonian mixed clastic-carbonates series were described.

An institutional collaboration was launched by the Geological Survey of the Popular Republic of Angola with geologists from the Moscow Institute of Geology, which led to the publication of a new 1:1 million scale geological map of Angola (1988) and of an associated memoir (Perevalov et al., 1992).

The Agostinho Neto University hosted the activity of Morais et al. (1990), Morais & Sgrosso (1993), Duarte-Morais et al. (2001) who published on fieldwork geology near the Benguela area, in collaboration with the University of Naples. Those papers dealt mainly with Cretaceous sedimentology, particularly with Albian outcrops and their Campanian shaly cover. Those publications were subcontemporaneous with offshore and onshore seismic interpretations of Albian rafts by oil companies (Duval et al., 1992; Tillement, 1987). All this geological information was made available at the GeoLuanda 2000 Congress, which included two fieldtrips in the Sumbe-Benguela region. A selection of papers was published in the Africa Geoscience Review (2001). Guiraud et al. (2001) launched new geological fieldwork on Albian rafts in the area the same year.

Since 2002, collaborations and scientific research were launched with Portuguese, French, Swiss, Spanish, Polish, South African, American and Brazilian universities. Recent opening of new roads made the access to several regions easier, even though the existence of postwar landmines complicates the safety conditions. In Kwanza-south, the Catanda carbonatites were studied by Bambi et al. (2012), Campeny et al. (2014) and Jackowicz et al. (2014), through collaborations with the Universities of Barcelona and Warsaw. Next to Sumbe, Meister et al. (2011) identified a well-dated section at the Albian–Cenomanian boundary. Along the Benguela coast, Albian biostratigraphy and raft sedimentology was updated by Tavares et al. (2007) and Quesne et al. (2009), through a collaboration with the University of Dijon and the Natural History Museum of Geneva. Structural interpretation was also highlighted by Guiraud et al. (2010). In the Namibe area, Cooper (2003a, b) established the stratigraphy of coastal Cretaceous outcrops. Dinis et al. (2010) described a Gilbert Delta in Late Cretaceous coarse clastics. Strganac et al. (2014, 2015) revised Late Cretaceous series (Coniacian age of lava flows, time-gaps, paleoceanography…) to determine the stratigraphic context of the fossil dinosaurs discovered by Paleoangola, an academic group dedicated to the paleontology of dinosaurs in Angola since 2011. Sharp et al. (2012) published observations on Cretaceous travertine deposits, followed by L. Gindre-Chanu et al. (2014), who detailed the sedimentology of the “salt”. Marsh (2014) revised the age and geochemistry of coastal lava flows. Two studies (Sessa et al., 2013, Rosante, 2013) documented the recent and older uplift of the continental margin. Offshore, besides intense oil-exploration drilling in South-Kwanza (2000–2004, 2012–2015), revisions of the DSDP-364 well were published (Hartwig et al., 2012; Kochhann et al., 2013, 2014; Naafs & Pancost, 2014), which emphasized the occurrence of Late Aptian deposits above the massive Loeme salt and the richness of source-rock of the first sedimentary units above the salt formation.

6 Conclusions

Following the first publications on the geology of Angola in the period 1875–1920, the coastal areas of South-West Angola, between Sumbe and Namibe, were described and mapped between 1926 and 1974 by the Geological Survey of the country, with the support of Portuguese universities, in collaboration with foreign universities until 2001. Besides observations on mineral resources (such as copper, gypsum or bitumen occurrences), various geological data were published during this period, especially on biostratigraphy in order to define the age and time-gaps of the Cretaceous series rich in diverse Ammonite fauna, and on Cretaceous igneous, alkaline, and carbonatitic rocks.

In the framework of various academic collaborations between the University of A. Neto and foreign universities and museums, an increasing number of publications were published between 2002 and 2014, mainly related to carbonatite peculiarities, oil exploration (coastal sedimentology of the Benguela Albian rafts, Namibe coastal geology), or paleontology, in particular dinosaur fossils. The improvement of geological knowledge in Angola has thus been fast–about a century–and was fueled by both economic and scientific reasons, and has led to a rich production of data and scientific papers that form the solid basis on the ongoing present researches and activities on natural resources.

Acknowledgements

This paper has been written in tribute to our late colleague and friend Jean-François Stéphan who was the thesis supervisor of Olivier Laurent and a strong support of his geologist career. This article has been reviewed by Teresa Salome Alves da Mota, Christian Meister, and Associate Editor Isabelle Manighetti.