1. Introduction

Variscan orogen displays widespread evidence of hydrothermal processes [e.g. Boiron et al. 2003; Bouchot et al. 2005; Gasparrini et al. 2006]. Various evidences of Late Hercynian fluid circulations have been documented in Central/South Armorican tectonometamorphic domains of the Armorican Massif (i.e., thick quartz veins, Lemarchand et al. [2012]; kaolinite-dickite high-temperature clay mineral assemblage in kaolin deposits [Gaudin et al. 2020], and numerous sulfides orebodies carrying Pb, Zn, Sb and Au indices [Chauris and Marcoux 1994]). Here we discuss a new Fe-sulfide occurrence of hydrothermal origin discovered in lower Ordovician sandstones at Montlouis, near Janzé (Ille-et-Vilaine), not far from several orebodies of the Central Armorican Domain (i.e. the abandoned mines of Pontpéan en Bruz near Rennes (Ille-et-Vilaine), La Touche-Vieux-Vy-sur-Couesnon (Ille-et-Vilaine) and Le Semnon (Ille-et-Vilaine) as well as the “Bois-de-la-Roche” quarry near Saint Aubin des Chateaux (Loire-Atlantique) [Chauris and Marcoux 1994; Gloaguen et al. 2007, 2016; Pochon et al. 2016a, b, 2019]).

Sulfides were analysed with laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICPMS) along with scanning electron microscopy to discuss element sourcing and partitioning between the various sulfide species. Except at Bois de la Roche near Saint Aubin des Chateaux, where electron microprobe analyses were performed on pyrite and associated sulfides [Gloaguen et al. 2007], it is the first time that Fe-sulfides involved in Armorican orebodies are analysed for trace elements. Our analyses identify some specific features compared with the other ores so far studied in the area such as Sb controlled by melnikovite and a Tl anomaly not yet recognized in that area. Montlouis is thus the first example of Tl anomaly in the Armorican massif and the third one in France after the unusual As–Sb–Tl paragenesis reported from Jas Roux (French Alps) [Johan et al. 1974], and geochemical indices documented in the Cévennes area [Aubague et al. 1982].

1.1. Montlouis quarry and its pyrite veins

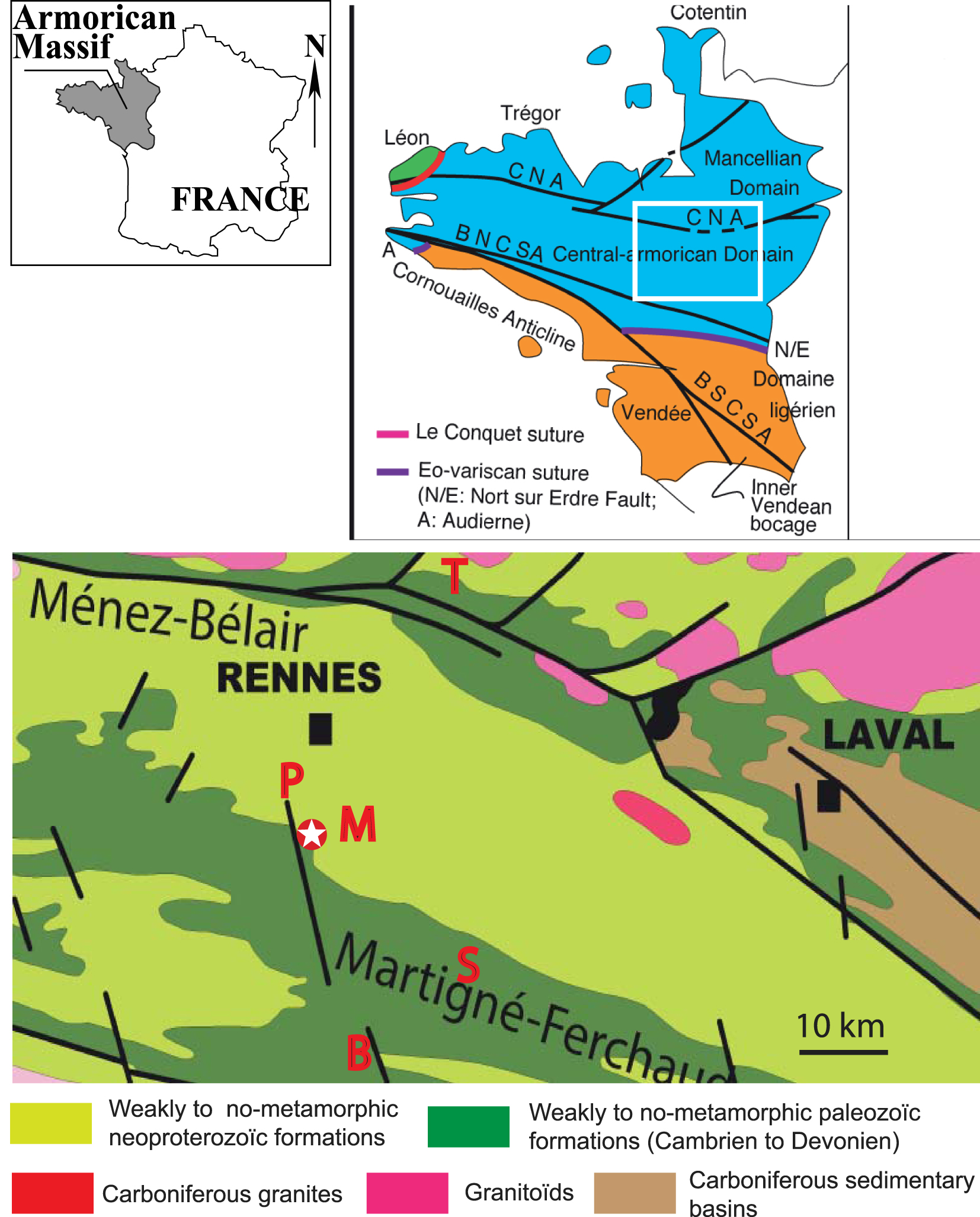

The Montlouis quarry, a 320,000 m2 open pit now operated by Lafarge Holcim™, is located near Janzé (Ille et Vilaine; France), 15 km to the north of Saint Aubin des Chateaux and 20 km to the southeast of Rennes, in the so-called “synclinorium of the south of Rennes” the Central Armorican Domain, (Figure 1). Here, folded paleozoic sediments rest unconformably on a neo-proterozoic basement made up from platform marine sediments [Gumiaux et al. 2004]. The Montlouis quarry is excavated within the Lower Ordovician sandstones of the “Grès Armoricain” formation. This detritic formation was deposited during an important marine transgression [Guillocheau and Rolet 1982]. The quarry is encasted between two kilometre-scale N–S trending vertical faults [Trautmann et al. 1994]. This fault system was inherited from late Variscan deformation [Le Corre et al. 1991; Gumiaux et al. 2004; Pochonet al. 2018; Pochon et al. 2019]. Sandstones are cross-cut by a body of deeply hydrothermally altered dolerite displaying sericitised plagioclase laths and skeletal Fe–Ti oxides (ilmenite, magnetite). Iron–Ti oxides are now replaced by rutile, pseudobrookite, and hematite and Ca-pyroxene by green amphibole, and epidote (pistachite), respectively. Similar rocks are widespread in the Central Armorican Domain [Trautmann et al. 1994] and the Armorican massif as a whole [Pochon et al. 2016a, b, 2019, and references therein].

Location and geological setting of the Montlouis quarry (sketch map of the Variscan domains of the Armorican massif and geological background after Faure, 2021, https://planet-terre.ens-lyon.fr/article/chaine-varisque-France-2.xml redrawn and colorized after Le Corre et al. 1991). CNA North Armorican shear zone; BNCSA: Northern branch of the S. Armorican shear zone; BSCSA: Southern branch of the S. Armorican Shear Zone. T: La Touche-Vieux-Vy-Sur-Couesnon; P: Pontpéan-en-Bruz; M: Montlouis; S: Le Semnon-La Coefferie; B: Bois-de-la-Roche.

The vein system discovered at Montlouis is poorly exposed over a few tens of square meters on the northern face of the quarry. It strikes along an overall N–S direction consistent with the late Variscan faulting system, although no reliable mean direction can be measured because of many discontinuities in the outcrop. Pyrite and the other Fe-sulfides identified (marcasite, melnikovite, galena, sphalerite) commonly occur as mm-scale to centimeter-thick veins showing no continuity on a larger scale, grading into sandstone breccias cemented by pyrite or diffuse impregnation of pyrite inside sandstones. Centimetric pyrite cubes are also present in larger vugs opened inside sandstones and coated with a quartz gangue. No gradation between the two modes of occurrences could be observed.

2. Analytical methods

Montlouis Fe-sulfides were studied with an Olympus BH-2 dual reflected-transmitted light microscope and a Tescan VEGA II LSU scanning electron microscope (SEM) operating in conventional (high-vacuum) mode, and equipped with an SD3 (Bruker) EDS detector (platform of electronic microscopes; Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle Paris, France, MNHN). Major element concentrations were determined at 15 kV accelerating voltage with a PhiRoZ EDS standardless procedure. Accuracy was checked by repeated blind analyses of a natural troïlite-FeS (Del Norte County, USA) [Lorand et al. 2018].

LA-ICPMS analyses were done at the “Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géosciences; Nantes” using a Photon Machine Analyte G2 excimer laser (193 nm laser wavelength) coupled with a Varian 880 quadrupole ICP-MS through a cross-flow nebulizer. The largest pyrite crystals and their fibrous overgrowths were analysed on hand-picked crystals mounted in epoxy resin. Marcasite and columnar pyrite were analysed in-situ on polished thick sections. Spot sizes for standards and samples were set to 81 μm. Repetition rate of 10 Hz using a laser output energy of 90 mJ with a 50% attenuator and 20× demagnification produces low fluences on the sample (<4 J∕m2).

Details on the analytical procedures were reported by Lorand et al. [2018, 2021]. The following isotopes were collected: 29Si, 34S, 51V, 57Fe, 59Co, 60Ni, 61Ni, 63Cu, 65Cu, 66Zn, 75As, 77Se, 95Mo, 107Ag, 118Sn, 120Sn, 121Sb, 125Te, 126Te, 197Au, 205Tl, 207Pb, 208Pb and 209Bi. Isotopes of each element to be analyzed, length of analysis (for spots) and dwell time were set to minimize potential interferences and maximize counting statistics—with overall mass sweep time kept to ∼1 s. Major elements (S, Fe) were counted in the low-count rate mode to avoid saturation of detectors. External calibration was performed with synthetic standards MASS-1 [pressed Zn-sulfide powder; Wilson et al. 2002]. Each standard was analyzed twice every ten analyses to bracket sample measurements at the beginning and at the end of a single ablation run. Data reduction was done using Glitter™ software [Griffin et al. 2008]. Analyses of Fe-sulfides were quantified with S as internal standard, using 54 wt% as S concentration for pyrite and marcasite (Table 1) and 52 wt% S for melnicovite. Analytical precision was monitored by the repeated analysis of the sulfide standards yielding 10% RSD (relative standard deviation) for Au, Mn, Zn, Mo, Sb, Tl, Pb and Bi and 10–15% RSD for Co, Ni, Cu, Cd, Se and Ag.

Representative major element analyses of Montlouis Fe-sulfides

| Mineral wt% | Py | Py | Mrc | Mrc | Ml | Ml | Ml |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | 46.56 | 46.62 | 46.50 | 46.17 | 43.04 | 45.77 | 44.46 |

| Sb | - | - | - | - | 4.90 | 4.0 | 3.50 |

| S | 53.4 | 53.83 | 53.50 | 53.13 | 52.06 | 50.25 | 52.06 |

| Total | 99.96 | 100.45 | 100.0 | 99.30 | 100.0 | 100.02 | 99.92 |

| Metal/sulfur atomic ratio | 0.5 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.52 | 0.51 |

Py: pyrite; Mrc: marcasite; Ml: melnikovite.

3. Fe-sulfide mineralogy

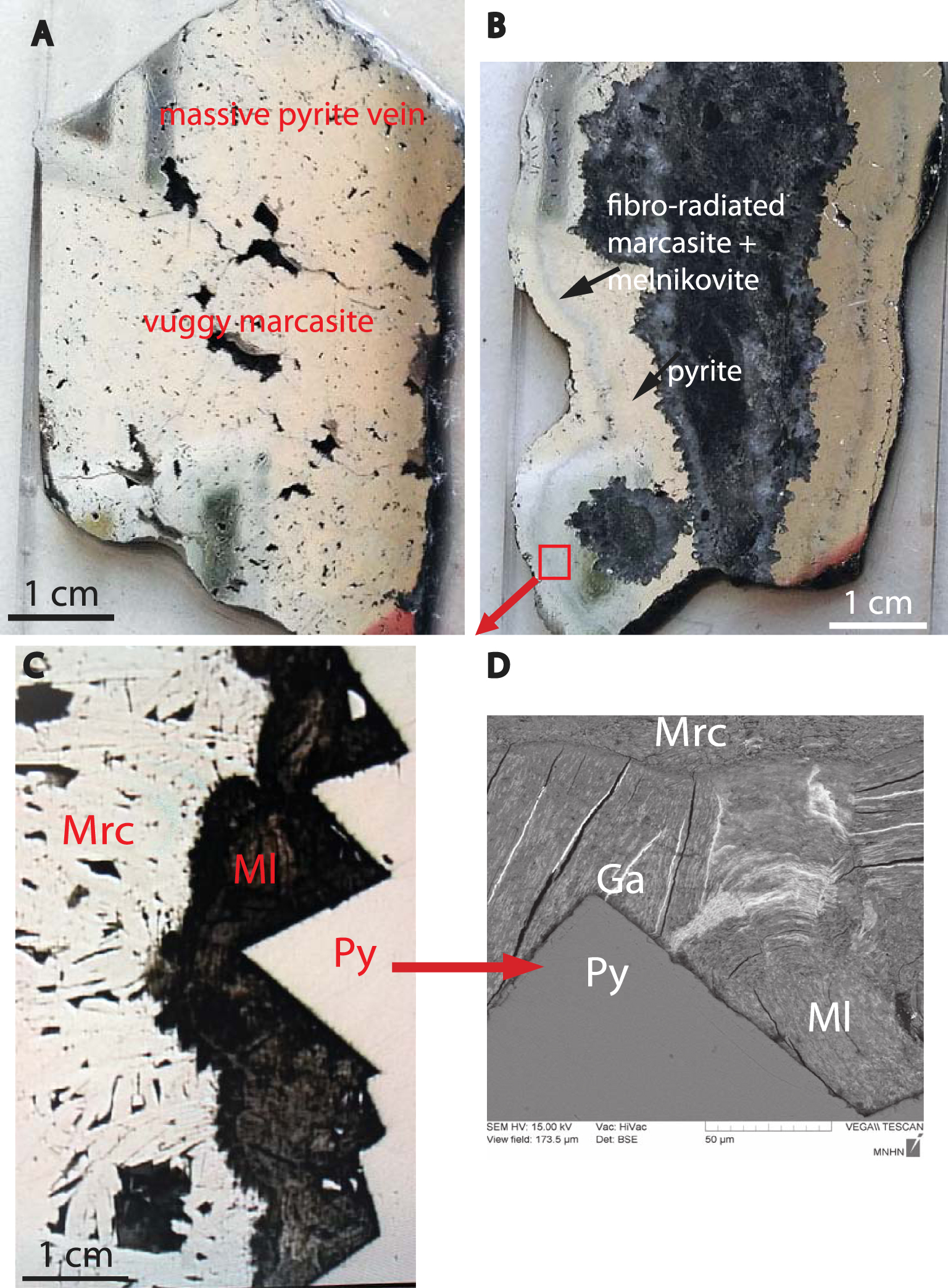

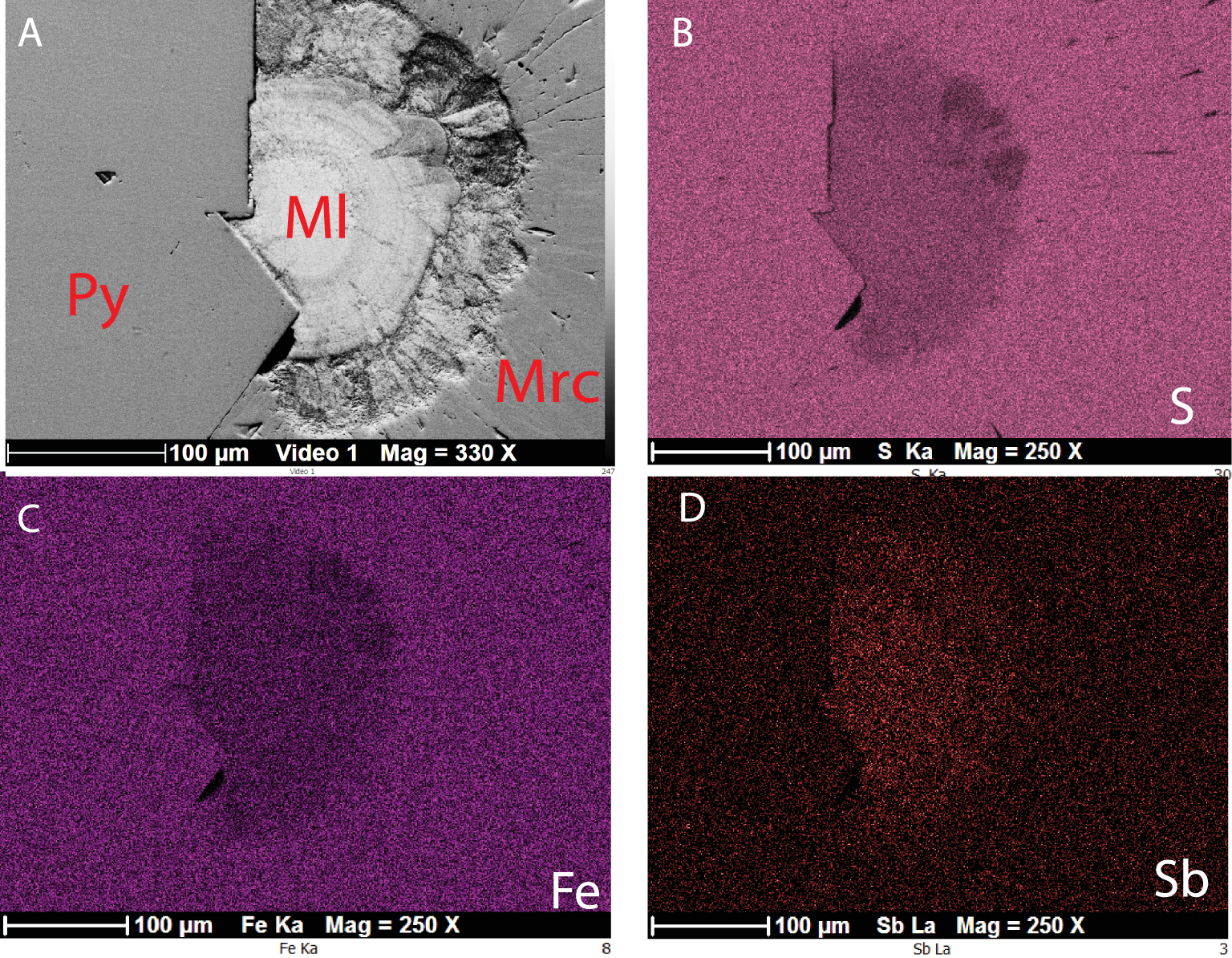

Pyrite is by far the most abundant Fe-sulfide. Massive pyrite veins are made up from anhedral pyrite partly replaced by marcasite (Figure 2A). This latter may show up characteristic crystalline faces (i.e. (001), (110), (011) or (010)). Some pyrite veins show mineralogical zonation, often reported as banded textures in Fe-sulfide ores [e.g. Kucha and Stumpfl 1992] (Figure 2B). The inner zone is composed of elongated pyrite crystals (columnar habit), terminated by cubic crystalline faces. The outer zone is occupied by fibroradiated marcasite. The contact zone between pyrite and marcasite is marked by botryoidal to colloform concentrically-layered spheroids up to 100 μm in diameter, looking like melnikovite, often reported as colloform pyrite [Ramdohr 1980]. As usually reported in classic textbooks [Picot and Johan 1977; Ramdohr 1980], this compound appears much darker than pyrite in reflected light, tarnishing when stored in air (Figure 2C). It has lower reflectivity compared to coexisting pyrite [e.g. Kucha and Stumpfl 1992] and display strong but false anisotropy in crossed-polarized reflected light. SEM picture of melnikovite reveals radial and concentric contraction cracks now filled with galena (Figure 2D). Back scattered electron images of concentrically-layered spheroids show inhomogeneous patchy zoning with some lighter areas characterizing heavier elements than Fe and S (Figure 3). This element is identified as Sb by X-ray scanning maps.

(A) polished thick section of a pyrite vein showing several vugs filled with marcasite (plane polariser reflected light). (B) Fe sulfide banded texture composed of an inner zone of elongated pyrite crystals (columnar habit), terminated by cubic crystalline faces and an outer zone of fibroradiated marcasite (plane polariser reflected light). (C) Detail of the contact zone between pyrite (Py) and marcasite (Mrc) showing botryoidal to colloform concentrically-layered spheroids of melnikovite (Ml) (plane polariser reflected light). (D) Back-scattered electron (BSE) image of melnikovite aggregates showing radial and concentric contraction cracks now filled with galena (Ga).

(A) BSE image of a melnikovite spheroïd (Ml) showing patchy zoning. Note the brightness of melnikovite compared to both pyrite (Py) and marcasite (Mrc). (B–D) X-ray maps showing attenuated Fe and S intensities compared to both pyrite and marcasite while Sb is identified as the heavy element of melnikovite.

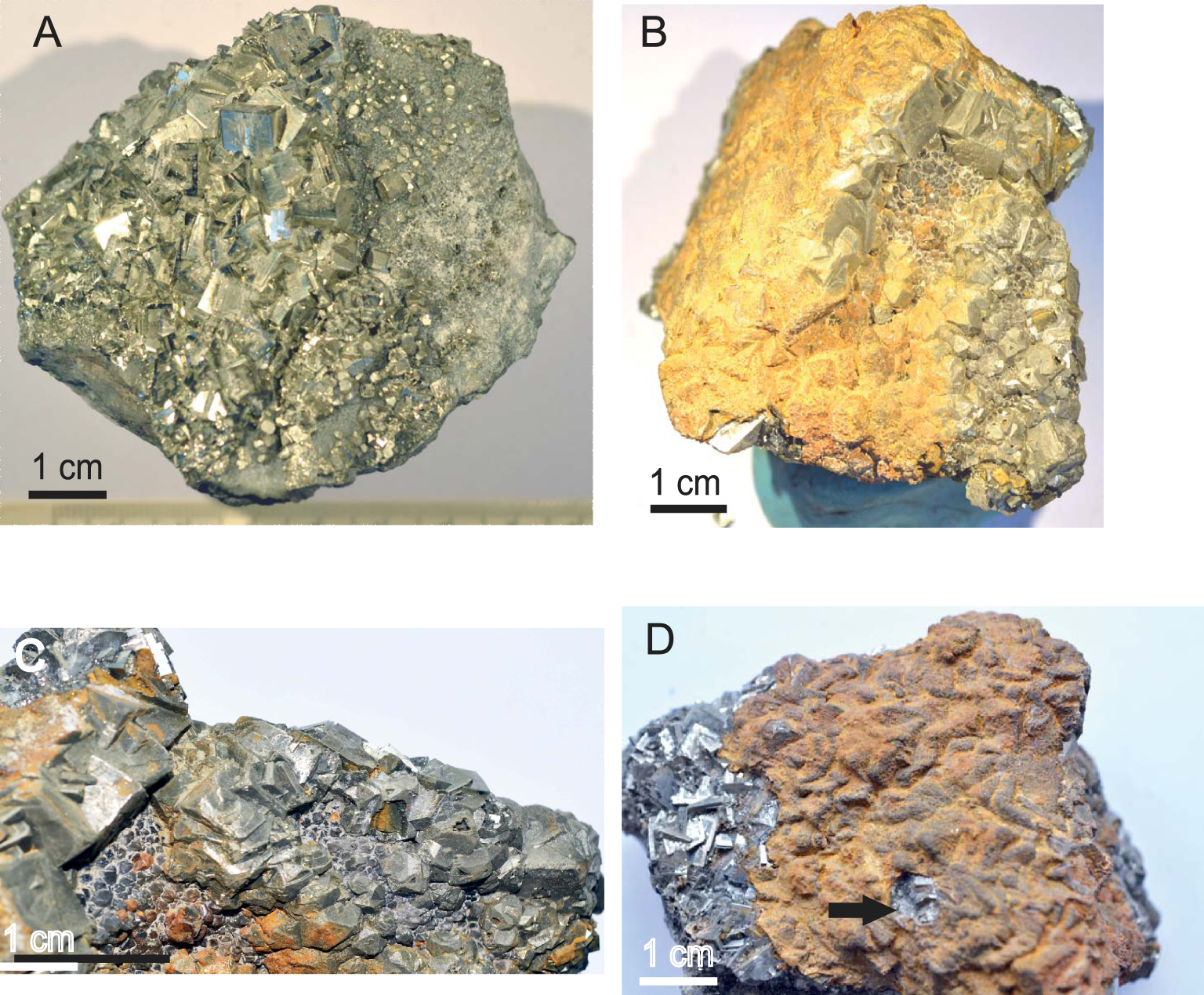

Vug-hosted euhedral pyrites usually display a darker core and a shiny periphery with weakly developed octaedral crystalline faces (111) (Figure 4A). The smallest isolated pyrite crystals that grew upon pyramidal quartz display more complex cubo-octaedral crystals shape combining (111) octaedral faces with (210) truncature. Pyrite cubes are occasionally coated with a mm-thick fine-grained pyrite overgrowths that pseudomorph the original cubes while sometimes developing its own crystalline faces (i.e. the octaedral faces on a perfect cube substratum (Figure 4B,C)). This fine-grained pyrite overgrowth was observed to be isotropic under crossed-polariser reflected light. It is locally oxidized into goethite, thus getting a reddish-brown color (Figure 4D).

(A) Shiny cubic pyrite crystals sitting on pyramidal quartz and sandstone. (B) Pyrite cubes completely covered by fine-grained pyrite overgrowth, itself coated with clay minerals (bright yellow) (C) detail of specimen (B) showing the tarnished fine-grained pyrite overgrowth that pseudomorphs the original cubes. (D) Reddish-brown oxidized fine-grained pyrite overgrowth on cubic pyrite.

4. Major and trace element geochemistry

EDS analyses indicate closely similar mean atomic Fe/S ratios for pyrite, marcasite and melnikovite (Table 1). EDS spectra detected Fe, S and Sb as major elements in melnikovite, in agreement with back scattered electron images (BSE) and X-ray scanning maps (cf. Figure 3). Oxygen was systematically detected. According to Kucha et al. [1989], Kucha and Stumpfl [1992] and Kucha and Viaene [1993], natural melnikovite occurrences may be described as a variable mixture of disulfide and compounds with intermediate sulphur valencies. Sb-rich melnikovite seem to display distinct anisotropy as do As-rich variety [Ramdohr 1980].

All three Fe-sulfides identified at Montlouis are nearly devoid of Au, Mo, Se In, Cd, Bi, Zn (Table 2). Their S/Se (55,000) is within the range of hydrothermal sulfides [5000–100,000; Luguet et al. 2004; Layton-Matthews et al. 2013; Queffurus and Barnes 2015].

Representative LA-ICPMS analyses of Montlouis Fe sulfides (ppm)

| Element (ppm) | V | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | As | Se | Mo | Ag | In | Sn | Sb | Au | Tl | Pb | Bi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vein-hosted pyrite | |||||||||||||||||

| Montl5-4 | <0.032 | <7.76 | <58.66 | 43.25 | <5.26 | <0.095 | 2528.4 | <1.11 | <0.03 | <0.5 | <0.05 | <0.018 | 64.03 | <0.003 | 4 | 68.2 | <0.022 |

| Montl5-12 | <0.039 | <0.82 | <0.51 | 1.67 | <6.56 | <0.109 | 10,689.0 | <1.40 | <0.08 | <0.01 | <0.017 | <0.023 | 26.05 | <0.05 | 0.28 | 4.8 | <0.003 |

| Montl5-13 | <0.043 | <158.2 | <952.1 | 20.88 | <10.51 | <0.121 | 3795.9 | <1.45 | <0.25 | <0.12 | <0.005 | <0.023 | 37.5 | <0.025 | 0.84 | 34.9 | <0.001 |

| Montl3-15 | <0.012 | <0.21 | <0.29 | 2.61 | <3.83 | <0.063 | 1607.85 | <0.81 | <0.012 | <0.005 | <0.0034 | <0.015 | 45.9 | <0.003 | 1.5 | 1.7 | <0.001 |

| Melnikovite | |||||||||||||||||

| Montl3-2 | <0.017 | <3.53 | <0.47 | <0.59 | <3.10 | <0.048 | 714.9 | <3.1 | <1.04 | <0.003 | <0.0012 | <0.0119 | 11,369 | <0.002 | 140.7 | 11.85 | <0.001 |

| Montl3-6 | <0.016 | <0.060 | <0.215 | 0.98 | <7.75 | <0.43 | 567.9 | <2.1 | <0.5 | <0.004 | <0.001 | <0.011 | 10674.8 | <0.001 | 267.05 | 16.4 | <0.00 |

| Montl3-8 | <0.04 | <1.04 | <0.234 | 1.81 | <3.62 | <0.050 | 588.4 | <2.6 | <0.8 | <0.004 | <0.001 | <0.014 | 8884.3 | <0.001 | 106.95 | 1.58 | <0.012 |

| Marcasite | |||||||||||||||||

| Montl5-1 | <0.029 | <2.75 | <32.9 | <0.81 | <4.15 | <0.08 | 1084.6 | <1.09 | <0.67 | <7.1 | <0.12 | <0.029 | 3107.6 | <0.017 | 63.6 | 7632.1 | <0.001 |

| Montl5-7 | <0.023 | <3.57 | <77.5 | 3.33 | <8.58 | <0.067 | 1020.5 | <1.00 | <1.15 | <8.5 | <0.125 | <0.062 | 3890.2 | <0.002 | 134.7 | 4941.9 | <0.001 |

| Montl5-10 | <0.022 | <1.02 | <9.71 | <1.16 | <4.32 | <0.066 | 810.5 | <1.02 | <1.2 | <4.1 | <0.06 | <0.024 | 3383 | <0.002 | 71.75 | 3843.7 | <0.007 |

| Montl5-17 | <0.032 | <2.02 | <51.67 | 2.07 | <6.24 | <0.093 | 981.5 | <1.25 | <0.68 | <2.7 | <0.05 | <0.053 | 2734.5 | <0.003 | 40.2 | 1949 | <0.001 |

| Vug-hosted pyrite cubes | |||||||||||||||||

| Montl-2-1 | <0.041 | <0.37 | <0.64 | 5.65 | <6.50 | <0.127 | 1721.8 | <1.80 | <0.165 | <0.111 | <0.002 | <0.036 | 30.3 | <0.002 | 1.9 | 4.78 | <0.03 |

| Montl-2-3 | <0.056 | <0.41 | <0.65 | 5 | <4.52 | <0.106 | 1375.5 | <1.41 | <0.212 | <0.142 | <0.002 | <0.04 | 26.5 | <0.003 | 1.6 | 4.15 | <0.002 |

| Montl-4-1 | <0.049 | <0.189 | <0.87 | <5.84 | <15.41 | <0.185 | 79.3 | <0.12 | <0.036 | <0.014 | <0.002 | <0.050 | 11.14 | <0.004 | 0.4 | 1.4 | <0.002 |

| Montl-10-1 | <0.067 | <0.28 | <1.67 | <5.12 | <12.44 | <0.184 | 225.5 | <3.47 | <0.048 | <3.75 | <0.002 | <0.045 | 3.63 | <0.023 | 0.04 | 0.44 | <0.015 |

| Fine-grained pyrite overgrowth | |||||||||||||||||

| Montl-5-3 | <0.029 | <0.119 | <0.71 | 2.84 | <7.20 | <0.093 | 12.6 | <1.62 | <1.124 | <0.0312 | <0.001 | <0.024 | 492.2 | <0.002 | 2032.95 | 32.9 | <0.002 |

| Montl-6-1 | <0.030 | <0.116 | <1.03 | <2.47 | <8.91 | <0.087 | 20.1 | <1.58 | <1.11 | <0.038 | <0.001 | <0.023 | 680.9 | <0.002 | 1920.4 | 70.9 | <0.005 |

| Montl-6-3 | <0.031 | <0.127 | <0.76 | <3.20 | <7.22 | <0.090 | 18.1 | <1.72 | <0.967 | <0.0196 | <0.001 | <0.023 | 603.8 | <0.009 | 1797.37 | 60.1 | <0.001 |

| Montl-8-3 | <0.043 | <0.163 | <0.96 | 3.15 | <9.68 | <0.102 | 2.1 | <2.08 | <1.09 | <0.0187 | <0.001 | <0.024 | 438.7 | <0.002 | 1179.6 | 0.47 | <0.003 |

| Montl-9-1 | <0.046 | <0.189 | <1.36 | 6.47 | <9.58 | <0.21 | 2.75 | <2.41 | <1.043 | <0.152 | <0.002 | <0.028 | 173.5 | <0.002 | 295.4 | 4.51 | <0.045 |

Vein-hosted columnar pyrite displays up to 952 ppm Ni, 155 ppm Co and 43.8 ppm Cu (Table 2). They are strongly As-enriched (up to 10,600 ppm) for low Sb (<317 ppm) and Pb (<510 ppm) contents and no specific Tl concentration anomalies (Figure 5A,B). Vug-hosted pyrite cubes and their fine-grained secondary pyrite overgrowth show much lower transition metal contents (<21 ppm Ni; <2 ppm Co). They also display moderate As-enrichment (<2754 ppm) and low Pb (<7.8 ppm), Sb (<38 ppm) and Tl (<3.4 ppm) contents (Figure 5A,B). Pyrite overgrowths are strongly Tl-enriched (up to 2033 ppm) and much lower in As (<20 ppm) than the other pyrite habits. Thallium positively correlates with Sb (<680 ppm). Nickel, Co and Cu are below detection limits (1 and 0.2 ppm, respectively) (Table 2).

(A, B) Binary plots of trace elements for Montlouis Fe-sulfides.

Marcasite crystals show similar Ni and Co contents (up to 172 and 29 ppm, respectively) as their host columnar pyrite veinlet. Their strong Pb-enrichment (up to 7641 ppm) is noteworthy, as are their high Sb (<4000 ppm) and As contents (<1592 ppm). Lead positively correlates with Sb and Sb with As, respectively (Sb/As close to 3; Figure 5A). Thallium is detected, yet at much lower concentrations than in fine-grained pyrite overgrowths (<163 ppm).

Colloform melnikovite aggregates are As-depleted compared to their pyrite substratum (<700 ppm). Semi quantitative energy dispersive spectrometry (EDS) analyses indicate up to 5 wt% Sb (Table 1) while LA-ICPMS analyses yield lower but highly variable Sb contents (Sb < 11,400 ppm vs. 50,000 ppm; Figure 5A,B). Because it was larger than “melnikovite” spheroids, the laser beam intercepted composite marcasite-melnicovite aggregates rather than single-phase melnicovite, which diluted the actual Sb concentrations. Sb and As weakly correlate (Sb/As > 17; Figure 5A). A weak positive correlation seems to exist between Sb and Tl, yet melnikovite aggregates are only slightly enriched in Tl (<267 ppm) (Figure 5B).

5. Discussion

5.1. Constraints from ore mineralogy

Pyrite–marcasite–melnikovite assemblages are common low-temperature (<300 °C) hydrothermal mineralisations [Gemmell and Simmons 2007]. Ore mineralogy of Montlouis mineralization suggests that pyrite precipitated first as large cubes and massive veins after quartz, then followed by melnikovite/marcasite and/or fibrous pyrite overgrowths. Pyrite ore-forming solutions typically show near-neutral pH, are moderately reducing, and contain significant amounts of H2S and minor CO2 [Wang et al. 2010; Gartman and Luther 2013]. The largest veins and cubic crystals precipitated under near equilibrium, under a low degree of supersaturation in the fluids because cubic crystals and cubo-octahedral form spontaneously from H2S fluids, without requiring a high degree of supersaturation because cubes have the lowest Gibbs free energy of formation and their {100} faces have the lowest atom density and the highest growth rates [Murowchick and Barnes 1986, 1987; Keith et al. 2016; RickardLuther 2007; Wang et al. 2010; Barnard and Russo 2007]. The octahedral {111} faces that rarely appear in the smallest pyrite cubes have higher atom density, and thus slower growth rates. The sequence pyrite–marcasite can be ascribed to decreasing pH during ore precipitation. Pyrite indicates maximum pH < 9, and log fO2 − 36 to − 30 at 300 °C [Vaughan and Craig 1978] while octahedral pyrite may indicate local excursion of pH to 11, stabilizing polysulfide species [Wang et al. 2010; Gartman and Luther 2013]. Marcasite was reported to form only at pH < 4 (<5–6) and in presence of elemental sulfur [Murowchick and Barnes 1987; Schoonen and Barnes 1991; RickardLuther 2007]. This sequence of decreasing pH is supported by kaolinite infilling of pyrite vugs [pH < 6; cf. Sher et al. 2013].

Melnikovite was often interpreted as bertierite (FeSb2S4) replacement product [Picot and Johan 1977; Achimovičová and Balaz 2008]. This interpretation could account for the high Sb content measured in Montlouis melnikovite. However, as it predates marcasite, a primary origin is more likely for melnikovite: the contraction cracks testify to process of reduction connected with a reduction in volume. A similar primary origin was postulated for melnikovite by Kucha and Stumpfl [1992] in Bleiberg banded pyrite structure (Austria); they concluded that such compounds with mixed S valencies can be the natural precursor for banded sulfides formed below 250–300 °C. Thiosulfates species are unstable in acidic environments and soluble in water. The paragenetic succession pyrite–melnikovite–marcasite observed in the Montlouis ore is therefore consistent with the decreasing pH of solutions carrying Fe and S, as discussed above. It also suggests input of oxidized S alternating with reduced S that reflect flutuation in redox potentials. According to Kucha et al. [1989] both Pb and Sb may decrease the solubility of thiocomplexes, thus precipitating these latter as melnikovite. This process could account for the intimate associated between galena and Sb-rich melnikovite in Montlouis Fe sulfide ores.

5.2. Trace element constraints

As shown by SEM analyses and time-integrated laser-ablation analyses, submicroscopic inclusions of sphalerite and galena are very scarce in Montlouis Fe-sulfides and no other mineral inclusion were detected in the three Fe-sulfides. Trace element incorporation likely operated mainly by stoichiometric and non-stoichiometric substitutions. Among elements entering pyrite as stoichiometric substitution, Ni, Co, Se are of specific interest as they are temperature-sensitive elements, being typically enriched in sulfides that precipitate at high temperatures [e.g. Abraitis et al. 2004; Keith et al. 2016]. The Ni concentration level of Montlouis columnar pyrite (corresponding to 0.1 mol.% NiS2 at best) is consistent with the low-temperature origin of this epithermal deposit (<300 °C). At 500 °C, pyrite can dissolve up 10–11 mol.% NiS2; [Vaughan and Craig 1978; Lorand et al. 2018]. At first sight, the extremely low Se concentrations in Montlouis pyrites also support a low-T formation because Se is a low-solubility elements that precipitate at high T (>350 °C) in terrestrial active hydrothermal vents and is commonly enriched in corresponding high-T sulfides [Keith et al. 2016; Maslennikov et al. 2020]. Taken as a whole, all three Fe-sulfides display extremely low Se/As ratio, as expected for low-temperature hydrothermal sulfides [Reich et al. 2013].

Trace element concentrations bear evidence for a late stage enrichment in Sb, Pb and Tl in the Montlouis orebodes, i.e. marcasite for Pb, fine-grained pyrite overgrowth for Tl and melnikovite for Sb. The LA ICPMS time-resolved down-hole ablation profiles of marcasite, melnikovite and fibrous pyrite were smooth indicating that Tl, Sb and Pb are dissolved in the sulfide matrix, or occur as homogeneously distributed nanoinclusions. The fact that Tl and Sb moderately correlate in the fine-grained pyrite coating the largest pyrite cubes suggests that the coupled substitution of Tl+ + (As, Sb)3+ for 2Fe2+ documented by D’Orazio et al. [2017] also operated in Montlouis pyrite. However, Tl is bigger than Fe, Ni and Co. Rather than mineral/fluid equilibrium partitioning, a kinetic effect could explain why Tl was concentrated in fibrous pyrite aggregates rather than in more massive pyrite. Duchesne et al. [1983] pointed out that Tl is preferentially enriched in minerals presenting a colloform texture. Likewise, Maslennikov et al. [2020] documented preferential concentrations of Tl in fine-grained pyrite and marcasite precipitated from mid- and low-temperature fluids, the contents of these elements declining with increasing crystal size. George et al. [2019] also suggested that Tl could occur in structural defects in pyrite. Fine-grained pyrite overgrowth textures may therefore indicate disequilibrium conditions resulting from rapid crystallization, perhaps due to mixing between hydrothermal fluid batches [Berkenbosch et al. 2019]. This sequence of event is not uncommon in low-temperature hydrothermal ores: colloform, radiated, and oscillatory-zoned marcasite along with Tl-rich pyrite were documented in late disseminated sulfides or the outer walls of volcanic-hosted mineralization associated with vent chimneys [Smith and Carson 1977; Sobbot et al. 1987; Maslennikov et al. 2020, and references therein]. These latter authors describe sooty colloform marcasite becoming black which looks like melnikovite.

5.3. Montlouis Fe-sulfide ores and Central Armorican variscan mineralizations

There is little doubt that the Montlouis ore veins belong to the same Variscan mineralized province as the Pb–Zn–Sb–Au orebodies hosted in the Central Armorican Domain, not far from Montlouis. All of these orebodies appear to be driven by faults of broadly NW–SE direction which were recognized at La Touche (Vieux-Vy-sur-Couesnon) [Tanon 1961, unpublished report], Le Semnon Sb–Au orebodies [northern limb of the Chateaubriant anticline; Pochon et al. 2016a, 2019] and the Bois-de-la-Roche quarry (Saint Aubin des Chateaux; southern limb of the Châteaubriant anticline) [Gloaguen et al. 2007]. Dolerites that are spatially associated with Montlouis Fe sulfide veins are also present in the Pontpéan Pb–(Zn) ore [Lodin 1908; Moussu and Prouhet 1957, unpublished report] and as dike swarms at Le Semnon [Pochon et al. 2016b]. Some mineralogical similarities can also be recognized. The La-Touche orebody consists in massive pyrite–marcasite–melnikovite–pyrrhotite following Ag-rich sphalerite and galena in the paragenetic sequence [Chauris 1977; Pillard et al. 1985]. At Pontpéan a pyrite–sphalerite–galena ore is overgrown by pyrrhotite, itself replaced by botryoidal marcasite spheroids (or melnikovite ?) with fibroradiated texture [Moussu and Prouhet 1957, unpublished report; Chauris 1977]. At Le Semnon, pyrite and marcasite replace an early Fe–As–(Au) ore stage consisting of arsenopyrite [with numerous inclusions of Sb-sulfosalts; Gloaguen et al. 2016; Pochon et al. 2016a] while in the Bois-de-la-Roche quarry, the oolitic ironstone horizons (OIH) intercalated in Lower Ordovician sandstones is replaced by stratoid pyrite lenticular bodies with euhedral arsenopyrite inclusions and marcasite (locally up to 50 vol.%). Pyrite is also expressed in a second hydrothermal event with quartz, chalcopyrite, sphalerite and galena assemblage [Gloaguen et al. 2007].

The Montlouis orebodies display a sequence of geochemical anomalies that are also consistent with those reported for the Sb-ores i.e. an As positive anomaly associated with the earliest pyrite that contains similar As concentration levels as in Bois-de-la-Roche type-1 pyrite [Gloaguen et al. 2007] while the latest sulfides (marcasite, melnikovite and fibrous pyrite overgrowths) are characterized by overall increase of Pb and Sb contents. Stibnite is a late precipitate compared with pyrite–melnikovite–marcasite in the La Touche orebody [Chauris 1977] as are berthierite and the main Sb mineralization at Le Semnon [Gloaguen et al. 2016; Pochon et al. 2016a; Pochonet al. 2018] and Pb–Sb–Au-sulfosalts in the Bois-de-la-Roche quarry [Gloaguen et al. 2007]. However, there are major differences compared to Le Semnon or Bois de La Roche deposits such as the lack of pyrrhotite and arsenopyrite, while neither Sb sulfides/sulfosalts nor native antimony or gold have been identified so far at Montlouis. Compared to Pontpéan and Vieux-Vy sur Couesnon ores, the scarcity of Pb–Zn sulfides (galena, sphalerite) in Monlouis veins is noteworthy.

The Montlouis Fe-sulfide veins thus provide a further evidence for a large-scale Sb mineralizing peak in the southeastern part of the Central Armorican Domain. Pochon et al. [2017] concluded that Sb was sourced in the 360 Ma-old alkaline continental flood basalts that produced dolerites dikes. This origin may also pertain to the Montlouis pyritic veins which are spatially associated with a doleritic dike. Moreover, the high Ni/Co ratio of columnar pyrite points to contribution from hydrothermally altered mafic minerals such as olivine or pyroxene that are present in altered dolerite [Kaasalainen et al. 2015; Patten et al. 2016, and references therein]. With this interpretation, an upper age of ca 360 Ma, the age of magmatic crystallization of dolerites, can be inferred for Montlouis Fe sulfide veins. These latter, however, are likely younger. According to Pochon et al. [2017], hydrothermal alteration that liberated Sb involved a complex two-stage model postdating magmatic crystallization of dolerites. Moreover, N160° E-trending faults that control Sb–Au ores were active from the Early Carboniferous to the Early Permian [Pochon et al. 2019]. Most Variscan hydrothermal mineralizations were dated between 335 and 315 Ma [e.g. Chauris and Marcoux 1994].

The thallium concentration of Montlouis pyrite is the most distinctive feature compared to the other Pb–Sb–Au ores of the Central Armorican domain. It is the first Tl anomaly reported in the Armorican massif and the third one in France after the unusual As–Sb–Tl paragenesis from Jas Roux (French Alps) [Johan et al. 1974], and geochemical indices of Tl-rich marcasite documented in sedimentary Mesozoïc deposits from the Cevennes [Aubague et al. 1982]. In the Jas Roux ore, like in Montlouis pyrite, Tl precipitates at the latest stage of the ore forming event(s), namely after stibnite [Johan et al. 1974]. Thallium, like Sb and Pb has properties of highly volatile, fluid-mobile elements that are easily transported by hydrothermal fluids [Ryan and Chauvel 2014, and references therein].

A potential source for Tl is the altered dolerite body that is assumed to have provided Ni, Co and Sb to Montlouis Fe-sulfides. Thallium shows lithophile behavior in magmatic rocks and behaves as a highly incompatible element during magmatic differentiation, correlating with K, Rb, Sr, and Ba [Shah et al. 1994; Rader et al. 2018; Calderoni et al. 1983]. Therefore altered feldspar and micas are potential reservoirs for Tl [D’Orazio et al. 2017]. The elemental association of Tl, Sb, and As is also known worldwide in stratiform basin-hosted sulfide deposits (e.g. Carlin-type deposits Nevada, USA) [D’Orazio et al. 2017, and references therein] where pyrite can incorporate extremely high Tl contents (up to 35,000 ppm) as reported by Zhou et al. [2005] for the Xiangquan deposit (China). It is worth noting that, like Montlouis Fe-sulfides, the few Tl-bearing orebodies documented so far in France are hosted in sedimentary rocks, either dolostones or detrital rocks [Johan et al. 1974; Aubague et al. 1982] as is the Vedrin deposits (Belgium) that shows Tl-rich fibrous marcasite (6800 ppm Tl) [Duchesne et al. 1983]. If a sedimentary component was involved in Montlouis pyrite, then it has to be searched for in Middle ordovician slatty schists overlying ordovician sandstones of the “Grès Armoricain” formation. These black schists show compositional features of anoxic shales which are known to be strongly enriched in heavy metals due to organic material and microbial activities [e.g. Brumsack 2006; Algeo and Maynard 2004]. One may speculate that this sedimentary source was locally tapped by downgoing hydrothermal fluids. As discussed before, a mixing process between different hydrothermal fluid batches may account for the fine-grained pyrite overgrowth textures reflecting disequilibrium conditions. It is also consistent with the decoupling between Tl and Sb, Pb and As in that fine-grained pyrite (Figure 5B).

6. Conclusion

The Montlouis ores belong to the Variscan mineralizing event that led to Pb–Zn–Sb–Au orebodies hosted in the Central Armorican Domain. Pyrite veins display low-temperature (<300 °C) mineral assemblages of pyrite, marcasite, “melnikovite” with trace amount of galena and sphalerite. This mineral sequence is consistent with crystallization from near-neutral, moderately reducing, H2S-rich hydrothermal fluids evolving toward acidic conditions.

Stibnite, Cu sulfides and Pb–Sb sulfosalts are absent, unlike the other Sb–Pb ores of the Central Armorican domain. Trace element analyses identify As, Tl, Sb and Pb anomalies carried by Fe-sulfides, i.e. columnar vein pyrite (up to 1.0 wt% As), “melnikovite” (up to 5 wt% Sb), marcasite (up to 7600 ppm Pb) and fibrous pyrite overgrowths (up to 2060 ppm Tl). Potential reservoirs for Sb and Tl could be altered dolerite body observed in the quarry, or the middle Ordovician Angers-Traveusot black schists.

Conflicts of interest

Authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jean-Luc Bourguet (Lafarge Holcim) for providing access to the Montlouis quarry and his help during collection of the samples studied. We thank Laurent Lenta (LPG) for preparing the polished sections and Carole La (LPG) for her help during Laser-Ablation inductively coupled-mass spectrometry analyses. The present version of the paper was greatly improved through thorough reviews of Yves Moëlo and an anonymous reviewers, and careful reading of Eric Marcoux and associate editor Michel Faure. Their contributions are warmly acknowledged. Financial support was provided by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS-UMR 6112).

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0