1. Introduction

The Sahel, the semi-arid region just south of the Sahara, is frequently subjected to long years of drought. This bioclimatic zone is defined by rainfall levels between isohyets of 250 mm and 500 mm, an 8–10-month dry season and steppe vegetation (Casenave and Valentin, 1989). Rainfall is highly variable across years. Climatic fluctuation and climate change, combined with anthropogenic pressures on the environment such as overgrazing and the abusive use of chemical fertilizers for agriculture, among others, have led to the degradation of ecosystems, accompanied by biodiversity loss and increased poverty of local populations (Zwarts, Bijlsma, van der Kamp and Wymenga, 2009; Zwarts, Bijlsma, van der Kamp and Wymenga, 2012; Zwarts, Bijlsma, and van der Kamp, 2018). This is why African heads of state, in a 2005 meeting of the African Union (AU), took the decision to set up a restoration project, which they named Great Green Wall (GGW). The aim of this project is to restore Sahelian ecosystems weakened by the dual impact of climate (drought) and human activity (extensive livestock farming). Eleven African countries are involved in the GGW project, which in its original conception covers a strip 7800 km long and 15 km wide, between the Atlantic Ocean and the Red Sea (the Senegal segment is 550 km long).

The establishment of the GGW inspired the creation in 2009 of the International Human-Environment observatory (OHMi) Téssékéré, a partnership between France’s CNRS and the Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar (Senegal). The OHMi is one of 13 Human-Environment Observatories established by the CNRS. All are based on a founding ternary (https://www.inee.cnrs.fr/fr/ohm): a socio-ecological framework, a disrupting event and a focal object. For the OHMi Téssékéré, the first element is the socio-ecological context of the northern Sahel, where the primary mode of subsistence is extensive pastoralism, with ecological challenges posed by scant and irregular rainfall and heavy anthropogenic pressure. The focal object is the Sahelian savannahs of the Ferlo region of northern Senegal. The disrupting event is the establishment of the GGW. The aim of the OHMi is to study, through an interdisciplinary and multi-scale approach, the medium-term impacts of the GGW on Sahelian socio-ecosystems, including both human populations and the environments with which they interact (A. Guissé et al., 2013).

Before the creation of the OHMi, ecological, health and demographic data were either completely unavailable or too fragmented to be very useful. The initial work of the OHMi has thus consisted in building up baseline data that will enable monitoring the impact of the implementation of the GGW. Alongside research activities, OHMi Téssékéré has contributed to restoration activities of the GGW, planting trees and favoring natural regeneration in protected plots. The OHMi also includes a component aimed directly at poverty alleviation and local development (e.g., diffusion of multi-purpose village gardens), a sine qua non for the project’s acceptance and success.

Work carried out by the OHMi is thus multi-sectoral, and increasingly interdisciplinary, exploring the manifold links between biodiversity, ecosystem services, the local economy, and human health (Sandifer et al., 2015; Agence Panafricaine de la Grande Muraille Verte (APGMV), 2018). The first aim of this article is to present, on the basis of work carried out by OHMi Téssékéré researchers, baseline data on the environment and its plant and animal biodiversity. The second aim is to begin to analyze the impacts of the GGW on biodiversity and its implications for the development and improved well-being of human populations in Senegal’s Ferlo region. Restoration of ecosystems takes time, typically decades, and the GGW, facing numerous challenges in this semi-arid environment, is no exception. Although the full impact of the GGW cannot yet be judged, we point to promising directions for the future.

2. The International Human-Environment observatory Téssékéré : an integrative model of international cooperation based on scientific research

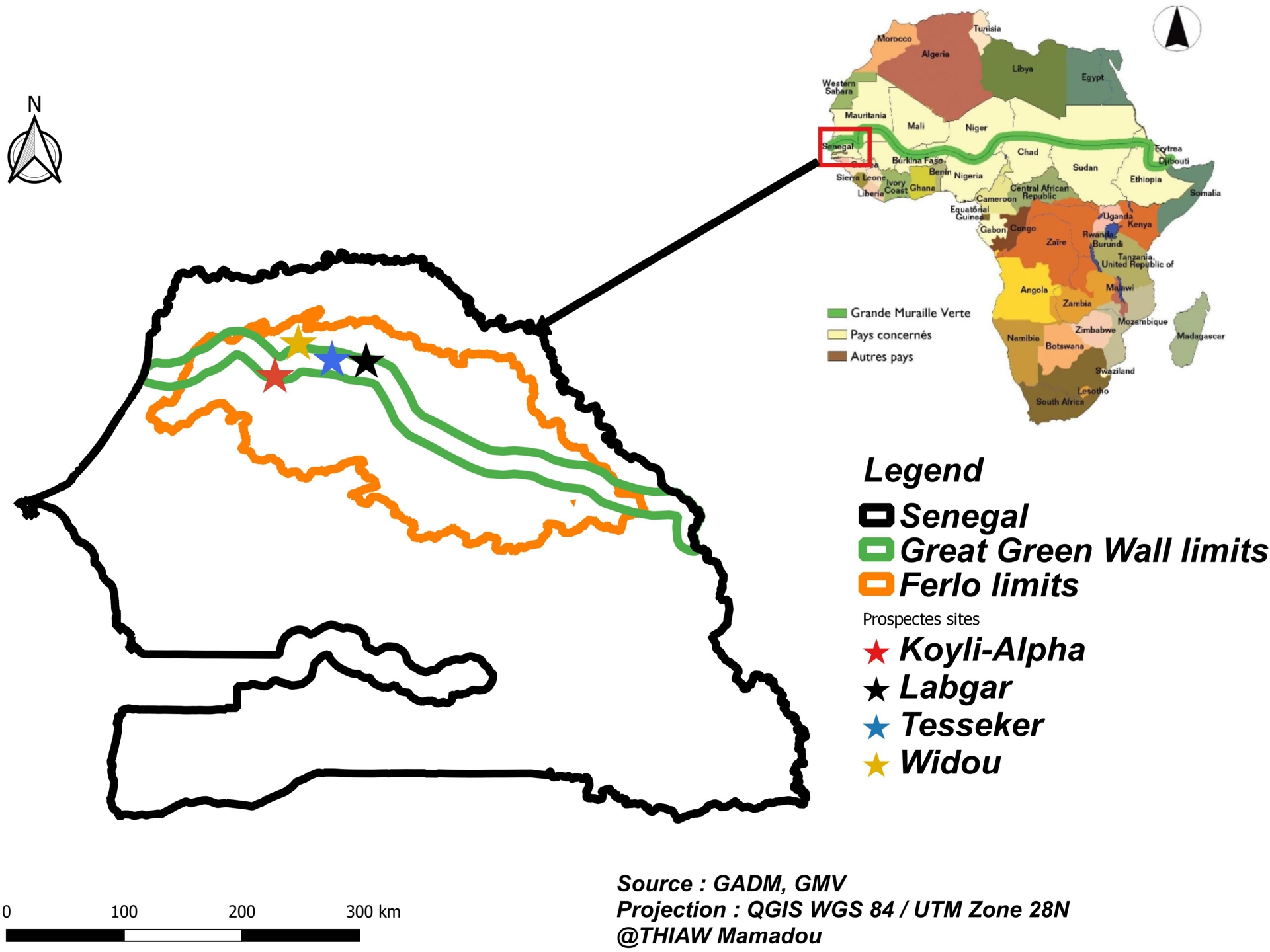

More than 100 researchers, post-docs, PhD students and Master’s students at several universities and research institutions in Africa and Europe work under the auspices of the OHMi Téssékéré. Work within the OHMi Téssékéré currently focuses on four major themes: biodiversity, health, water and soil, and social systems. Most of the work has been carried out at Koyli Alpha, Widou, Téssékéré and Labgar (Figure 1).

Localization of the study area.

Biodiversity is the basis of essential environmental services on which life on the planet depends. Consequently, its conservation and sustainable use are of paramount importance. Habitat degradation and resource overexploitation are particularly crucial as drivers of biodiversity loss across Africa. Information on biodiversity is incomplete for many organisms. Preserving an area’s natural biodiversity and the genetic diversity of harvested species can boost resistance to insect invasions and disease outbreaks, thereby reducing agricultural losses. For all these reasons, identifying locations of high biodiversity for several major groups, allowing the protection of a large proportion of biodiversity in a comparatively small area, is an important research objective (Scholes et al., 2006). To this end, researchers from a variety of backgrounds and specialities have been involved in the activities of OHMi Téssékéré to generate knowledge about biodiversity and ecosystem services in the GGW route area. This knowledge currently covers:

- Plant biodiversity, species recommended for reforestation, and local people’s uses and perceptions of vegetation;

- Animal biodiversity, with identification of current and extinct fauna, and local people’s uses and perceptions of wildlife;

- Interactions between fauna, flora, domestic animals and human populations.

2.1. Plant biodiversity

The phytoecological characterization of ecosystems plays an important role in the study of Sahelian ecosystems in Senegal. The mapping of land use along the GGW route by Sylla et al. (2019) provided an initial opportunity to determine the current state of plant communities and their spatio-temporal dynamics. The results obtained in the municipality of Téssékéré showed 13 land-use units and their current state. These are wooded savannah, shrub to wooded savannah, shrub savannah, wooded steppe, shrub to wooded steppe, shrub steppe, market gardening, rainfed cultivation and fallow land, residential areas, ponds, bare areas and areas occupied by tree plantations. There is great diversity and dominance of the “natural vegetation formation” category (in reality, “semi-natural”), with eight classes occupying over 90% of the surface. All 13 land-use units were present in 1984, i.e., after the great drought of the 1970s, with the exception of the plantation class, which today occupies 2.04% of the surface. The conversion of land to plantations is due to tree-planting campaigns of the GGW, whose first interventions in the area began in 2008. Overall, analysis of changes in land use showed that 27.5% of the municipality’s surface area remained in its initial state, 65.5% underwent modifications and 7% conversions.

Several studies have characterized woody vegetation in different areas within the Ferlo (O. Ndiaye et al., 2013; Ndong, O. Ndiaye, M. N. Faye, et al., 2015; Kebe et al., 2020), recording 35, 38, and 23 species, respectively. Combining the results of the three studies, the total is 82 woody species, representing 55 genera and 26 families. While there is substantial overlap in species composition between the western part of the study area (Sahelian climate), and the eastern part (Sahelo-Soudanian climate), the latter is more diverse (73 species, 47 genera and 22 families) than the former (44 species, 36 genera and 17 families). The most represented families are Fabaceae (21 species), Combretaceae (12 species), Capparaceae (7 species), Malvaceae (6 species), Apocynaceae (5 species), Moraceae and Rubiaceae (3 species of each family). In this flora, the genera Acacia (now divided into three genera) and Combretum are best represented, with 11 and 8 species respectively. The former genus Acacia has been revised; African species are now placed in the genera Senegalia (including the former A. Senegal) and Vachellia. In its present circumscription, the genus Acacia is restricted to Australia. Balanites aegyptiaca (Zygophyllaceae) is the most abundant species along the route. In the Sahelo–Sudanian sector, Combretum glutinosum (Combretaceae), Balanites aegyptiaca and Guiera senegalensis (Combretaceae) are the most frequent. In the Sahelian zone, on the other hand, the most frequent species are Balanites aegyptiaca, Vachellia tortilis subsp. raddiana, Boscia senegalensis (Capparaceae) and Leptadenia hastata (Apocynaceae).

Herbaceous cover in the region is dominated by grasses, among the most abundant species being Aristida mutabilis, Schoenefeldia gracilis and Cenchrus biflorus (Ndong, O. Ndiaye, M. N. Faye, et al., 2015). Forbs (non-graminoid herbaceous plants) are more diverse but occupy a smaller proportion of cover. Miehe et al. (2010) recorded 131 species of herbaceous plants in the Ferlo, including 40 species of Poaceae and 91 species of forbs. Work on the herbaceous stratum by OHMi researchers has focused on the impact of protection from grazing on biodiversity and vegetation structure (Badji et al., 2020) and on the importance of topographic depressions and ponds in conserving this biodiversity (N. Faye et al., 2020). N. Faye et al. (ibid.) compared herbaceous vegetation in two grazed depressions and one ungrazed (fenced) depression near Widou Thiengoly. They found a total of 55 herbaceous species, distributed across 41 genera and 22 botanical families. Protection from grazing had a marked effect on species composition and richness, vegetation cover, and plant growth, all being higher in the fenced depression. That plot was also the only one that harboured certain species that are rare in the region. These results underline the importance of opographic depressions and ponds in biodiversity conservation in this semi-arid region (Dendoncker, Vincke, et al., 2023).

Results of Badji et al. (2020) and N. Faye et al. (2020) show that protection from grazing can make a significant contribution to restoring ecological functions in the GGW area. While the results presented concerned herbaceous plants, which, with their short life cycles, respond quickly to restoration efforts, our results indicate that protection from browsing can also benefit trees. The potential for natural regeneration in protected plots is very high for the following tree species: Acacia tortilis, A. raddiana, Balanites aegyptiaca and Boscia senegalensis. For other woody species, such as Terminalia leiocarpa (formerly named Anogeissus leiocarpus; Combretaceae), Grewia bicolor (Malvaceae), Sclerocarya birrea (Anacardiaceae) and Sterculia setigera (Malvaceae), among others, the potential for natural regeneration is extremely low or non-existent, both inside and outside the protected plots. Most of these species originate from old, non-spiny (and generally less drought-resistant) stands that are currently dying back in Senegal’s Sahelian ecosystems as a result of climate change.

2.2. Animal biodiversity

The GGW project was initially announced as a reforestation project. Perhaps some people thought it was going to be limited to this objective. This was not the case, as the implementation of activities and the involvement of researchers through the OHMi Téssékéré demonstrated the need to involve several disciplines with mixed teams of researchers. Thus, following the identification of the tree species most suitable for reforestation, other researchers turned their attention to herbaceous plants and to wildlife, in particular insects, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals, and to ecosystem services provided by biodiversity.

2.2.1. Insects

Restoration initiatives in the Ferlo region have mainly focused on trees, and few studies have taken an ecosystem-wide approach to examining the interactions between organisms. Biotic interactions play a central role in ecosystem function and resilience (Carlucci et al., 2020; Dicks et al., 2021). Our research on insect-flower interactions provides an entry point to explore the diversity of biotic interactions and their contributions to ecosystem function (Kevan, 1999).

Insects play a predominant role in the pollination of angiosperms, making them key players in ecosystems. Maintaining their interactions with flowering plants is a key part of the success of ecological restoration (Dirzo et al., 2014; Genes and Dirzo, 2022). In the context of the GGW, our aim is to provide baseline data on the diversity of insect floral visitors and begin to study the impact of the initiative’s interventions on this key component of ecosystem functioning.

The entomological literature for this region, and for the northern Sahel in general, is scattered in various specialist publications. There exists no synthesis of insect diversity in this region, especially in relation to insect pollination (Ollerton, 2017). The first goal of our work has thus been to characterize the diversity of flower-visiting insects in the region and assess its current status1 . This research is essential for studying the impact of GGW actions on ecological restoration. To do this, we sampled the diversity of flower-visiting insects in three insect-pollinated tree species with significant socio-ecological importance in the Ferlo region (O. Ndiaye et al., 2013; Ndong, O. Ndiaye, Sagna, et al., 2015; Dendoncker, Brandt, et al., 2020): Balanites aegyptiaca (the desert date; Zygophyllaceae), Vachellia tortilis (Mimosoideae, Fabaceae; formerly Acacia tortilis), and Ziziphus mauritiana (Rhamnaceae).

The study was carried out in the Ferlo region, in the vicinity of three villages along the Senegalese GGW layout, Ranerou, Koyli Alpha and Widou Thiengoly. Near each village, sampling was conducted in three kinds of sites differing in vegetation density and diversity: inside parcels in which trees had been planted, livestock excluded, or both; in areas that had not been planted with trees and were exposed to grazing and browsing; and in seasonally wet depressions around temporary ponds. We installed pan traps (yellow, white and blue) for during 48 hours, and caught insects visiting the flowers with a hand net during three days at different times of day (Westphal et al., 2008; Wilson et al., 2008). These two methods give complementary information about flower-visiting insects (for example, nocturnal insects were caught only in pan traps). Trees near all three villages were sampled at the end of the dry season, in May and June 2022. Balanites aegyptiaca flowers at different times of the year, enabling us to characterize seasonal variation in the composition of flower visitors. Thus, in one of the villages, Koyli Alpha, we carried out two more sampling campaigns in the wet season in August 2022 and in the middle of the dry season in February 2023.

Up to now, data have been compiled for one of the three tree species, Balanites aegyptiaca. Analysis of the insects collected at flowers of the other two species is ongoing. We found unexpectedly high insect diversity. For the one species for which insects have been determined (B. aegyptiaca), we found a total of 427 morpho-species visiting its flowers. These insects belong to 10 orders, among which Hymenoptera and Diptera predominated, accounting for 317 morpho-species (Tables 1 and 2).

Total diversity of insects sampled at flowers of Balanites aegyptiaca

| Order | Species richness | Abundance | Number of identified families |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hymenoptera | 201 | 4115 | 44 (13 superfamilies) |

| Diptera | 116 | 1272 | 40 (20 superfamilies) |

| Coleoptera | 41 | 275 | 16 (11 superfamilies) |

| Hemiptera | 38 | 402 | 14 |

| Thysanoptera | 12 | 281 | 1 |

| Lepidoptera | 7 | 229 | / |

| Neuroptera | 4 | 12 | 3 |

| Psocoptera | 4 | 7 | / |

| Orthoptera | 3 | 7 | 3 |

| Ephemeroptera | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Abundance of the six most abundant families of insects at flowers of Balanites aegyptiaca

| The six most abundant families | Abundance |

|---|---|

| Formicidae (Hymenoptera) | 2624 |

| Halictidae (Hymenoptera) | 553 |

| Chloropidae (Diptera) | 325 |

| Mythicomyiidae (Diptera) | 239 |

| Braconidae (Hymenoptera) | 291 |

| Phlaeothripidae (Thysanoptera) | 281 |

By a significant margin, the most abundant insects were ants, followed by Halictidae, a family of solitary or subsocial bees (Danforth, 2002; Danforth et al., 2008). Bees rely primarily on flowers as food resources as both adults and larvae, while the other insects captured at flowers can be part of several food webs. For instance, ants at flowers may collect nectar, but they also hunt prey; braconid wasps are parasitoids of other insects and use nectar to fuel their search for hosts (Jervis et al., 1993). Mythicomyiidae are abundant flower visitors in arid and desert regions throughout the world. As a sign of how much we still have to learn about the insect fauna of the region, very little is known about the life cycle of these abundant flies (Evenhuis, 2002). Hundreds of species await description.

Our research has unveiled an unexpected diversity of flower-visiting insects in Balanites aegyptiaca. However, our current dataset is insufficient to draw robust conclusions regarding the impact of the GGW. It is imperative that research efforts continue, including further sampling and monitoring in the Ferlo region, to assess the current status and trends in insect diversity. Research is also needed to determine the significance of the ecosystem services supplied by flower-visiting insects. Is pollination a limiting factor in fruit production by culturally and economically important trees? What roles do flower-visiting insects play in the regulation of populations of other insects?

This work aligns with the interdisciplinary research framework of the GGW. Beyond its field applications, the project aims to enrich our understanding of the social, ecological, and economic dynamics of the people residing in the Sahel region. Our research and data collection efforts are designed to make the most of this knowledge.

2.2.2. Amphibians and reptiles

Surveys carried out at Koyli Alpha, Widou Thiengoly, Téssékéré and Labgar, municipalities averaging about 21.3 km2 in area (range: 17–26 km2), revealed the presence in the Ferlo, documented by direct observations, of seven species of amphibians belonging to four families (Table 3) (Licata et al., 2025).

List of amphibian species observed in Ferlo, the total number of observations and their conservation status according to the IUCN (Licata et al., 2025, unpublished data)

| Families | Species | Number of individuals | IUCN status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bufonidae | Sclerophrys pentoni | 891 | LC |

| Sclerophrys xeros | 8 | LC | |

| Pyxicephalidae | Pyxicephalus edulis | 18 | LC (but decreasing) |

| Tomopterna milletihorsini | 68 | DD | |

| Hyperoliidae | Kassina senegalensis | 9 | LC |

| Ptychadenidae | Ptychadena schillukorum | 1 | LC |

| Ptychadena trinodis | 1 | LC |

LC = least concern; DD = not classified owing to insufficient data.

The information in Table 3 shows that the toad Sclerophrys pentoni is the most frequent species in the study area, with 891 sightings in 25 sampling days (i.e., 89.5% of total sightings), followed by the frog Tomopterna milletihorsini with 68 sightings, i.e., 6.8% of total sightings. The frog species Ptychadena schillukorum and P. trinodis were observed very rarely in the study area. All species observed are classified as “Least Concern” (LC) on the IUCN Red List. However, the total number of observations made for this study reveals the need for special measures to be taken by the authorities for their conservation in Ferlo. The species Ptychadena schillukorum and P. trinodis were observed only once each, both times at Koyli Alpha. This suggests their rarity in the Ferlo region.

To date, 11 reptile species have been identified in the area covered by the GGW in Senegal (Table 4). These belong to two orders and nine families. The order Squamata (lizards and snakes) is the best represented in the area, with eight families and 10 species. The only other reptile recorded is one turtle species. All the reptile species recorded in the region are classified as “Least Concern” on the IUCN Red List, with the exception of the Sebacean Python (Python sebae), which is “Near Threatened” (NT), and the ridged turtle (Centrochelys sulcata, Testudinidae), which is “Endangered” (EN). The ridged turtle had completely disappeared from this area of Senegal. The population observed in this study comes from a reintroduction of 20 individuals (L. Diagne and T. Diagne, 2019).

List of reptile species recorded in the GMV in Senegal (Thiaw, 2021), their French names, and their IUCN status

| Orders | Famiies | Species | French name | IUCN status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Squamata | Agamidae | Agama agama | Margouillat | LC |

| Gekkonidae | Stenodactylus petrii | Sténodactyle de Pétrie | LC | |

| Phyllodactylidae | Tarentola senegambiae | Tarente de Sénégambie | LC | |

| Scincidae | Chalcides delislei | Scinque du Sénégal | LC | |

| Varanidae | Varanus exanthematicus | Varan de savane | LC | |

| Varanus niloticus | Varan du Nil | LC | ||

| Boidae | Eryx muelleri | Boa des sables de Muller | LC | |

| Python sebae | Python de Séba | NT | ||

| Elapidae | Naja senegalensis | Cobra sénégalais | LC | |

| Viperidae | Bitis arietans | Vipère heurtante | LC | |

| Testudines | Testudinidae | Centrochelys sulcata | Tortue sillonnée | EN |

LC = least concern; NT = near threatened; EN = endangered.

2.2.3. Birds

A number of studies have been carried out in the past in the Senegal River valley (G. J. Morel and M. Y. Morel, 1978), particularly in the Djoudj National Bird Park and in the northern Ferlo, but none have focused on the GGW route area. These studies have shown the presence of significant avian biodiversity in this part of the country. In fact, of all the different regions of Senegal, the Ferlo has the highest concentrations of migratory birds during the migration period (Zwarts, Bijlsma, van der Kamp and Wymenga, 2012; Zwarts, Bijlsma, and van der Kamp, 2018; Zwarts, Bijlsma and van der Kamp, 2023a; Zwarts, Bijlsma, and van der Kamp, 2023b). Thus, following the observation of the importance of birds in ecosystems, the OHMi has been interested in bird biodiversity in Ferlo since 2011 (Roux-Vollon, 2012; A. Diop, 2020; A. Diop, N. Diop, Diallo, et al., 2023; A. Diop, N. Diop and P. I. Ndiaye, 2024a). We have currently identified 217 bird species, including 60 waterbird species. Almost half of the species identified are migratory (106 species), with palearctic migrants predominating. Examples include the Black-tailed Godwit (Limosa limosa), Turtle Dove (Streptopelia turtur) and Eurasian Spoonbill (Platalea leucorodia). Some species are classified at high protection levels on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species. These include the Black-tailed Godwit (Limosa limosa), Savannah Boater (Terathopius ecaudatus), Abyssinian Bucorva (Bucorvus abyssinicus), Turtle Dove (Streptopelia turtur), Scavenger Vulture (Necrosyrtes monachus), the African Vulture (Gyps africanus), Rüppell’s Vulture (Gyps rueppelli) and the Scavenger Vulture (Necrosyrtes monachus) (A. Diop, 2020; A. Diop, N. Diop, Diallo, et al., 2023; A. Diop, N. Diop and P. I. Ndiaye, 2024b). Owing to disturbances noted in the area of the Djoudj National Bird Park as a result of climate change and the development of rice cultivation in the Ferlo, some species such as pelicans, spoonbills and storks, which used to migrate only to this park, now come as far south as the Lac de Guier tributary south-east of Keur Momar Sarr, very near the Koyli Alpha community nature reserve.

2.2.4. Micromammals

Study of rodent populations

The results are based on trapping carried out between 2009 and 2016 in different habitats in three villages (Labgar, Téssékéré and Widou-Thiengoly) along the GGW route in Senegal: inside plots initially fenced off to exclude livestock and encourage the regeneration of woody vegetation (protected plots; two per locality), outside these plots (more or less degraded savannah areas and fields) and at the ecotone (edge) between these two habitats (see Granjon, Bâ, et al., 2019, for details of the methodology).

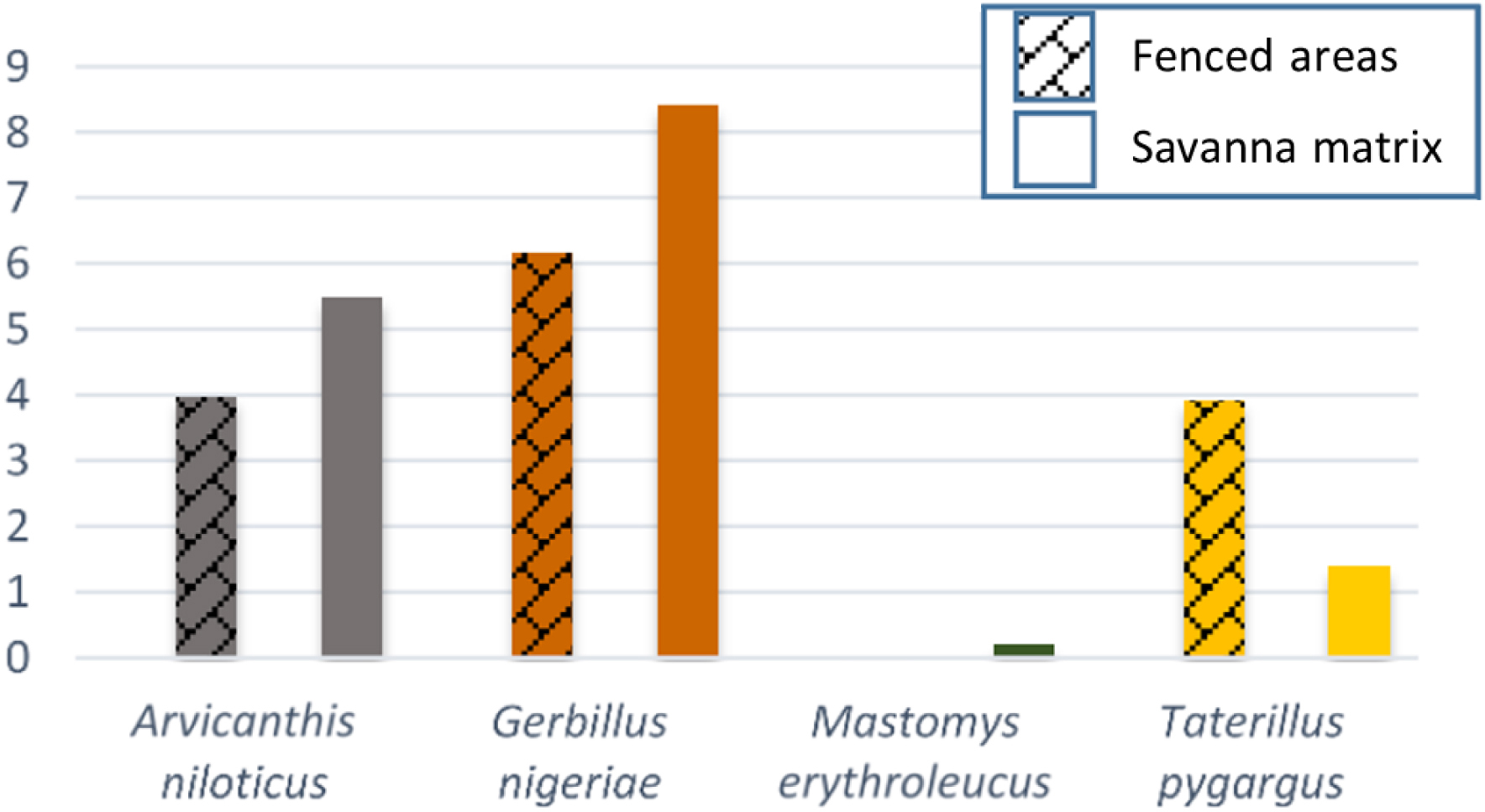

To test the hypothesis of an effect of fenced plots (and therefore of woody regeneration) on populations of terrestrial small rodents, we compared trapping results and the diversity of species assemblages between the “fenced” (i.e., fenced plots and their edges) and “non-fenced” (savannah and field habitat matrix) sets. The results (Table 5 and Figure 2) show no significant difference in stand composition between these two groups. Gerbillus nigeriae, Arvicanthis niloticus and Taterillus pygargus are, in that order of abundance, the species present, with a fourth species, Mastomys erythroleucus, having only been caught twice near a small pond outside the defended plots. On the other hand, the relative abundances of the three dominant species appear to be more equitable on the defended plots, resulting in a much higher diversity index for this category of plots (H′ = 2.47 vs. 1.39 outside the defended plots).

Trapping effort (in number of nights effective traps, cf. Granjon, Bâ, et al., 2019), results of trapping carried out in and outside of defended plots between 2009 and 2016 along the GGW in Senegal, and Shannon diversity indices for each species assemblage

| Trapping effort (trapnight number) | Arvicanthis niloticus | Gerbillus nigeriae | Mastomys erythroleucus | Taterillus pygargus | Total number of captures | H′ (Shannon) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fenced areas | 1510 | 60 | 93 | 0 | 59 | 212 | 2.47 |

| Surrounding habitat matrix | 1096 | 60 | 92 | 2 | 15 | 169 | 1.39 |

Trapping yields (numbers of captures in relation to the effective trapping effort, expressed as percentages, see details in Granjon, Bâ, et al. (2019)) for the four rodent species captured in and outside the protected plots in the developed areas of the GGW in Senegal (villages of Labgar, Téssékéré and Widou Thiengoly).

In the GGW area of Senegal, due to environmental changes associated with the period of rainfall deficit from the 70s to the 90s as well as anthropogenic activities in the Sahel (Lebel and Ali, 2009; Miehe et al., 2010; Gonzalez et al., 2012; Bodian, 2014; Brandt et al., 2014; Walther, 2016), significant changes in the structure of local communities of small mammals have been observed over the last few decades (Granjon, Bâ, et al., 2019). Today, species adapted to aridity (Gerbillinae and among them species of the genus Gerbillus) or to habitats created/modified by man (A. niloticus in hedgerows around fields) dominate the Ferlo stand, where the majority of species 40 years ago was a species typical of Sahelian savannahs (T. pygargus, Poulet, 1972). The two species that dominate today’s assemblage (G. nigeriae and A. niloticus) are known to be harmful to crops and stored goods, as well as being potential reservoirs of pathogens transmissible to humans and livestock (Granjon and Duplantier, 2009; Dahmana et al., 2020).

2.2.5. Larger wild mammals

Work on large wild mammals (LWM) began in 2015 with numerous surveys at Widou Thiengoly, Téssékéré, Labgar and then Koyli Alpha (A. Niang and P. I. Ndiaye, 2021b; A. Niang, 2023). We based our work on the classification of Kassa et al. (2022), who define as large mammals those whose average weight is ⩾2 kg. Several study methods were used during the surveys: surveys of local populations, line transects, reconnaissance transects, fixed points, and camera trapping. Surveys were mostly conducted during the day, with nocturnal surveys on a few occasions. This was the first study of LWM in this part of the Ferlo. In further work, the team has concentrated on Koyli Alpha and the surrounding area. This work has shown the presence of nine species of LWM, eight of which are nocturnal (Table 6).

Repertory of the large wild mammals encountered in the GGW area. Indications to evaluate their relative abundance are presented in two publications (A. Niang and P. I. Ndiaye, 2021b; A. Niang, 2023)

| Orders | Families | Species | French name | UICN red list category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carnivora | Canidae | Canis aureus | Chacal doré | LC |

| Vulpes pallida | Renard des sables | LC | ||

| Felidae | Felis silvestris | Chat sauvage | LC | |

| Herpestidae | Atilax paludinosis | Mangouste des marais | LC | |

| Mustelidae | Ictonyx striatus | Zorille | LC | |

| Mellivora capensis | Ratel | LC | ||

| Viverridae | Genetta genetta | Genette commune | LC | |

| Lagomorpha | Leporidae | Lepus capensis | Lièvre | LC |

| Primates | Cercopithecidae | Erythrocebus patas | Singe patas | NT |

LC = least concern; NT = near threatened; DD = not classified.

According to the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species, of these nine species only the Patas monkey is classified as “Near Threatened (NT)”, all others being of minor concern. However, while several widely distributed species such as the Cape hare, the pale fox and the golden jackal are globally of “least concern”, the poor state of conservation of their current habitats in Senegal makes it clear that special attention needs to be paid to the conservation of these species to avoid the risk of their disappearance in Senegal. There is a need to draw up a local red list of endangered species for better biodiversity management at the national level. In the course of our works, we have identified a loss of biodiversity in the Ferlo zone. We reported in A. Niang and P. I. Ndiaye (2021a) and A. Niang and P. I. Ndiaye (2021b) the decline of five species of LWM in Ferlo zone, among them the dorcas gazelle, the striped hyena and the leopard, which are classified as “Vulnerable”, “Near Threatened” and “Critically Endangered” respectively. The dorcas gazelle was disappeared from the Ferlo area for many years but, an attempt to reintroduce a few individuous from captivity has permited the repopulation of northern Ferlo. In this context, it is important to have information on locally extinct species so as to be able to envisage their reintroduction as part of the restoration of degraded ecosystems. This is the context in which the Sahelo-Saharan antelope Oryx algazelle (Oryx dammah) is being reintroduced into the Koyli Alpha Community Nature Reserve (A. Niang, 2023). The herd is currently adapting well to the reserve’s environmental conditions. In fact, at least four births a year have been recorded so far, for a herd of six individuals starting out in May 2020. This example shows that reintroduction can also be possible for other species that have disappeared from the area. The reintroduction of Gazelle dorcas (Gazella dorcas), Oryx algazelle and Gazelle dama (Nanger dama) into the Katané enclosure in Ferlo Nord (Abáigar et al., 2013) is a good model on which to base such actions along the GGW route.

2.3. Intra- and interspecific interactions

A return to rainier conditions (Bodian, 2014) and the rehabilitation of more treed habitats, for example via the GGW initiative (Dia and Duponnois, 2012; Boëtsch et al., 2019), could offer opportunities to rebalance the small mammal community, but more generally to help re-establish more diverse animal communities. The restoration of more complex ecological relationships, including parasitism, competition and predation, could in turn help the natural regulation of populations of rodents in the region (Krebs, 1999; Bianchi et al., 2006), following the example of what has been observed in temperate zones (Benedek and Sîrbu, 2018; Meyer et al., 2019) and in southern Africa (Starik et al., 2020). With regard to predation, the increase in tree density associated with the regeneration of woody species, an action at the heart of the GGW, should encourage the establishment of raptors that prey on small rodents such as the barn owl (Tyto alba, Thiam et al., 2008), which would thus benefit from more perches and nesting sites. The contribution of these predators to the control of small mammal populations (see Krebs (1999) and Labuschagne et al. (2016) for discussions on this subject), would fit in completely with the logic of ecological management in the framework of the operational expectations of the GGW (Dia and A. M. Niang, 2012).

The ecosystem interactions between restoration actions and the presence of insect and small mammal populations have therefore been studied and documented, thanks to the work of OHMi Téssékéré. A final major aspect of animal biodiversity has also played an important role: the study of bird populations. Insects and rodents form a large part of the diet of various predators, including birds, some of which feed exclusively on insects or rodents (G. J. Morel and M. Y. Morel, 1978). In fact, studies carried out at OHMi Téssékéré have shown that birds are more numerous in fenced plots (more Palearctic and intra-African migrants and vultures), as these plots offer better conditions for nesting, an abundance of food (insects for the black-billed hornbill, for example, and rodents for raptors) (Roux-Vollon, 2012). On the other hand, these plots are less frequented by granivorous birds, which prefer open-ground territories. Studies have also shown that fenced plots constitute refuge areas for resting and breeding for many species of birds and large mammals (A. Diop, 2020; A. Diop, N. Diop, Diallo, et al., 2023; A. Diop, N. Diop and P. I. Ndiaye, 2024a; A. Diop, N. Diop and P. I. Ndiaye, 2024b; A. Niang, 2023). Thus, from a bioecological point of view, the reforested perimeters, in addition to improving bioclimatic conditions, also contribute to the conservation of both animal and plant biodiversity.

A project on the scale of the GGW necessarily entails changes in many aspects of the environment and society, not just effects on flora and fauna. These changes, socio-economic and demographic, primarily concern human populations, and include the opening up of the area and associated transport infrastructure. Another important transformation is the increase in the number of boreholes, as well as the increased transport of water from boreholes to near hamlets and other residential areas. The widespread availability of water causes piosphere gradients (Shahriary et al., 2021) to flatten or disappear, with widespread heavy grazing, as more and more of the savannah is close enough to water to allow heavy grazing and browsing. The research carried out by OHMi Téssékéré has highlighted the importance of these transformations, which are indirectly linked to the installation of the GGW, leading to a co-construction between researchers from the disciplines of ecology and the humanities and social sciences.

2.4. Relations between people and their environment

The relationship between human populations and their environment in Senegal’s GGW zone is complex and multifaceted. The GGW is a project aimed at combating desertification and restoring degraded ecosystems in the Sahel region. In general, local populations rely heavily on ecosystem goods and services such as crop production, fishing, livestock breeding, hunting and gathering for their food security. Ecotourism is not yet well developed in this part of the Senegalese Sahel, but the establishment of the Koyli Alpha Community Nature Reserve suggests that it could play a major role in the economy of this part of the country, in addition to its functions in restoring degraded ecosystems. It is with this in mind that the Agence Sénégalaise de la Reforestation et de la Grande Muraille Verte (Senegalese Agency for Reforestation and the GGW) is joining the drive to multiply the number of community nature reserves along the route of the project to promote ecotourism and green employment in the Ferlo.

Indeed, according to Ngom et al. (2014), each type of ecosystem corresponds to different functions and services, which in turn depend on the health of the ecosystem, the pressures exerted on it, and the use made of it by societies in a given biogeographical and geo-economic context. Human societies use ecosystems, modifying them both locally and globally (Chevassus-Au-Louis et al., 2009). In turn, societies adjust their uses to the modifications they experience. This dynamic interaction characterizes what are known as socio-ecosystems (Walker et al., 2002). Several ethnobotanical studies in arid and semi-arid zones of Africa have shown the vital importance of vegetation for the well-being of local communities (Lykke et al., 2004; M. Diop et al., 2005; Ayantunde et al., 2009; Cheikhyoussef et al., 2011; Sop et al., 2012; Dendoncker, 2013; Gning et al., 2013; Sarr et al., 2013; Sagna et al., 2014; Sene et al., 2018).

Land restored through the GGW can provide more productive farmland and pasture for livestock, helping to improve food security. Village multi-purpose gardens in the Ferlo are a good example of an institutional initiative in the fight against rural precarity and for land restoration (Billen, 2015). Indeed, according to Billen (ibid.), the establishment of gardens offers a solution to two dimensions of women’s precarity in the Senegalese Ferlo: it enables an improvement in the quantity and quality of their diet, and promotes access to capital.

Access to fresh water is essential for local populations, both for human consumption and for livestock watering. Ecosystem services linked to watershed and water resource management are crucial to ensuring an adequate water supply. Water management will involve seeking a balance, assuring the water needs of people while minimizing the impact of widespread water availability on grazing pressure and pasture quality. In the Ferlo region, ponds play a key role in supplying local populations with water. In an area covering 3360 ha in the village of Widou, 244 ponds can be detected via satellite images (B. Faye, 2019). The density and cover of woody plants in ponds are higher in all areas studied (204.38 ind/ha and 39.41% in degraded areas; 201.86 ind/ha and 57.06% in advanced areas), and lower on slopes (38.8 ind/ha and 6.02%; 29.39 ind/ha and 7.62%) and plateaus (23.89 ind/ha and 2.85%; 17.87 and 4.53%). Creating pond-like habitats near boreholes could help compensate for increased grazing pressure near these artificial watering points.

Biodiversity in the region plays a key role in the provision of ecosystem services. Local species of plants provide resources for local species of animals that contribute to pollination, pest regulation and other ecological services. Biodiversity conservation is therefore an important aspect of the relationship between local populations and their environment. The woody stand contributes to the provision of six categories of provisioning ecosystem services: human food, fodder, traditional pharmacopoeia, energy wood, construction wood and craft wood (Ngom et al., 2014; K. Niang et al., 2014; Sagna et al., 2014; Sall, 2019; Sene et al., 2018).

Local populations play a central role in the management of natural resources such as land, water and vegetation. Sustainable management of these resources is essential to preserve ecosystem services in the long term. Climate change is having a significant impact on the Sahel region and in particular on the Ferlo, with more frequent droughts and more pronounced variations in rainfall. Local populations face challenges in adapting to these changes and maintaining their standard of living. The GGW involves land restoration actions, such as tree planting, fencing and other measures to combat desertification. These actions can have an impact on the way local populations use and manage their land.

In summary, the relationships between local populations and their environment in the context of Senegal’s GGW are deeply linked to the ecosystem services provided by local ecosystems. The sustainability of these relationships depends on the judicious management of natural resources, the conservation of biodiversity, and adaptation to the challenges of climate change. Promoting sustainable agricultural and land management practices is essential to ensure that local populations benefit from ecosystem services while preserving the environment.

3. Conclusion

In view of the complexity of the ecological interactions between trees and other plants and their biotopes, great caution is called for in the management of ecosystems in the GGW zone. It is in this sense that the main results obtained from the ecological study of Sahelian ecosystems in Senegal could be considered as starting tools to support restoration activities. For Senegal, which hosted the GGW’s first experiments, the results are encouraging; however, corrections are needed to achieve the objectives and expected results.

Once these multidisciplinary research foundations have been laid (those relating to plant and animal populations and their interactions), it becomes possible to envisage the implementation of much more interdisciplinary projects, thanks to the exchanges made possible by the operation of research structures such as the Observatoires Hommes-Milieux. In fact, by enabling all the researchers involved to work on the same research subject (i.e., the GGW in the case of OHMi Téssékéré), they enable the players to resonate with each other’s research, to receive insights from other points of view, and thus to bring out disciplinary issues in a more enlightened way.

This is the case in particular for the interactions between insect pollinator species and woody plants in the GGW, a project currently underway to analyze the structure of the pollinator community and its influence on the structure of the territory, as a function of the restoration of woody plants within the GGW (Medina-Serrano et al., 2025, and papers in preparation). Combining entomology, ecology and genetics, this project is the result of interaction between researchers working on the same subject. In addition, a project combining ecology, zoology and human and social sciences is also the fruit of this research: this project aims to reconstitute, document and compare the memory of the environment as experienced by local populations and researchers (Juillard et al., 2022; O. H. Guissé et al., 2024; Juillard, 2024).

Finally, as the GGW project involves local populations, the results of the research carried out by the OHMi are regularly communicated to them through popularized presentations made by the project leaders. These presentations enable local populations to grasp the scientific issues behind the research projects carried out in their territory, and are also an opportunity for researchers to integrate the questions raised by local populations into their research (OHMi (Observatoire Hommes-Milieux International Téssékéré), 2022; OHMi (Observatoire Hommes-Milieux International Téssékéré), 2024).

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Labex DRIIHM, French programme “Investissements d’Avenir” (ANR-11-LABX-0010), which is managed by the ANR (French National Research Agency). The authors thank all the authorities of the Labex DRIIHM and the OHMi Téssékéré, the local populations, particularly those of Koyli Alpha, and the GGW agency in Senegal (ASERGMV) for their help during this study. We also wish to thank the authorities of Cheikh Anta Diop University for the use of facilities during this work.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

1 This research has produced a review of insect-flower interactions in the Sahel (Medina-Serrano et al., 2025) and two papers in preparation (Medina-Serrano et al., unpublished results).

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0