1. Introduction

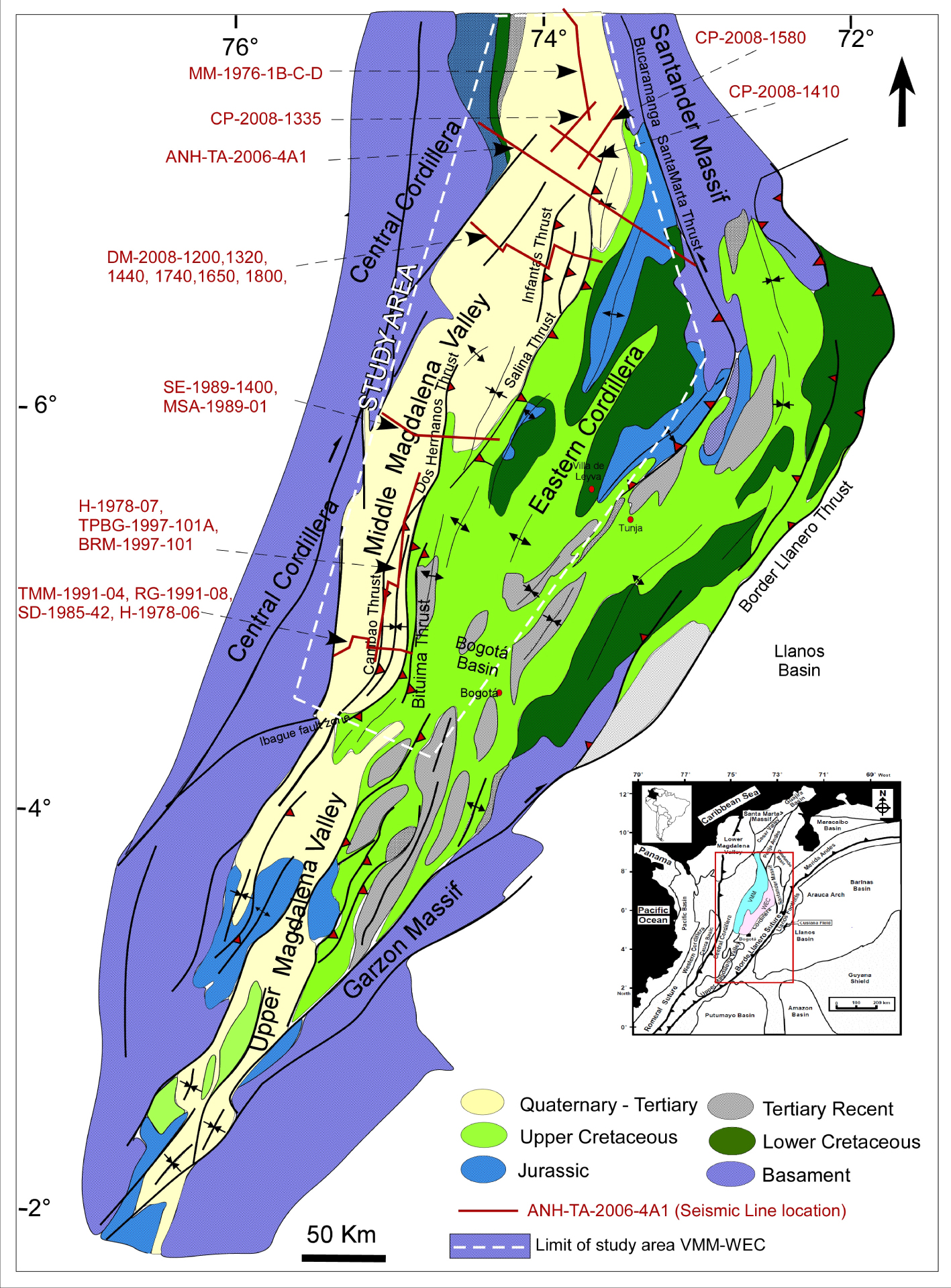

Map showing outcrops of Cretaceous units and main structural features of the Middle Magdalena Valley, Eastern Cordillera and Upper Magdalena Valley (modified from Restrepo-Paceetal 2004).

The study area covers the Middle Magdalena Valley basin (MMV) and the western part of the Eastern Cordillera Basin (WEC), with a particular focus on the MMV, which is a Cretaceous basin located between the Central Cordillera (CC) and the Eastern Cordillera (EC) (Figure 1). The MMV basin recorded several sea-level changes and sedimentary unconformities related to the North Andean active margin evolution. The Cretaceous, fine-grained marine successions of the MMV and WEC basins are classically considered as deposited in a syn-rift basin related to an extensional regime, without major compressional tectonic events [Cooper et al. 1995].

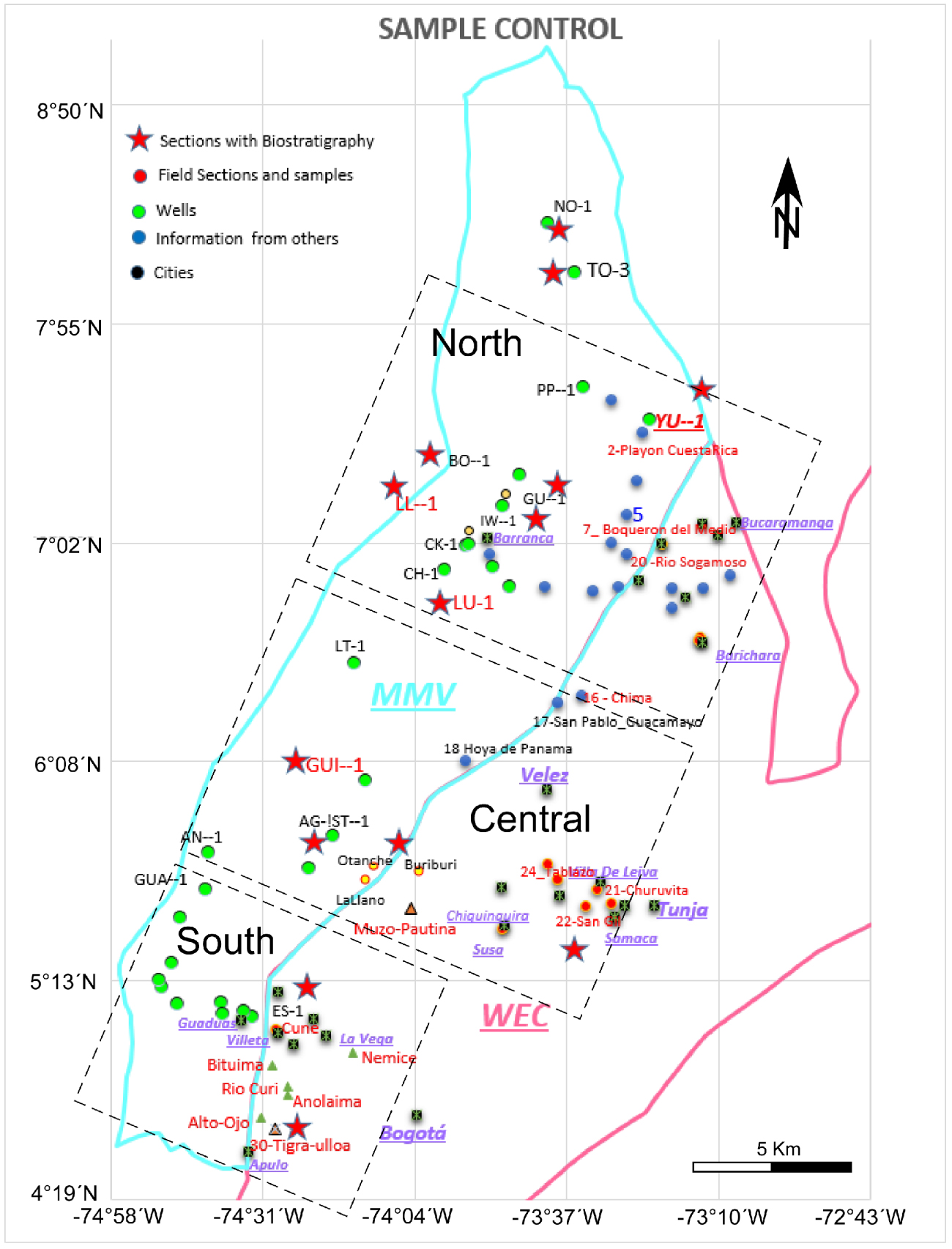

Location of wells and field sections. Green dots: wells; red dots: field sections and samples; blue dots: information from other authors; red stars: sections with biostratigraphy information; black dots: cities.

However, observations made in the whole Andean realm suggest that Cretaceous times were marked by some tectonic events, the nature of which needs to be specified. In Peru, Jaillard et al. [2000] indicate that the late Albian Mochica tectonic event was related to the high convergence rate along the Andean margin, due to the opening of the Atlantic Ocean at equatorial latitude. Equally, seismic information and biostratigraphic data led Jaimesde and de Freitas [2006] to recognize Cenomanian sedimentary hiatuses in the Upper Magdalena Valley (UMV), while Cooney and Lorente [2009] identified a Campanian unconformity in the Maracaibo basin in Venezuela.

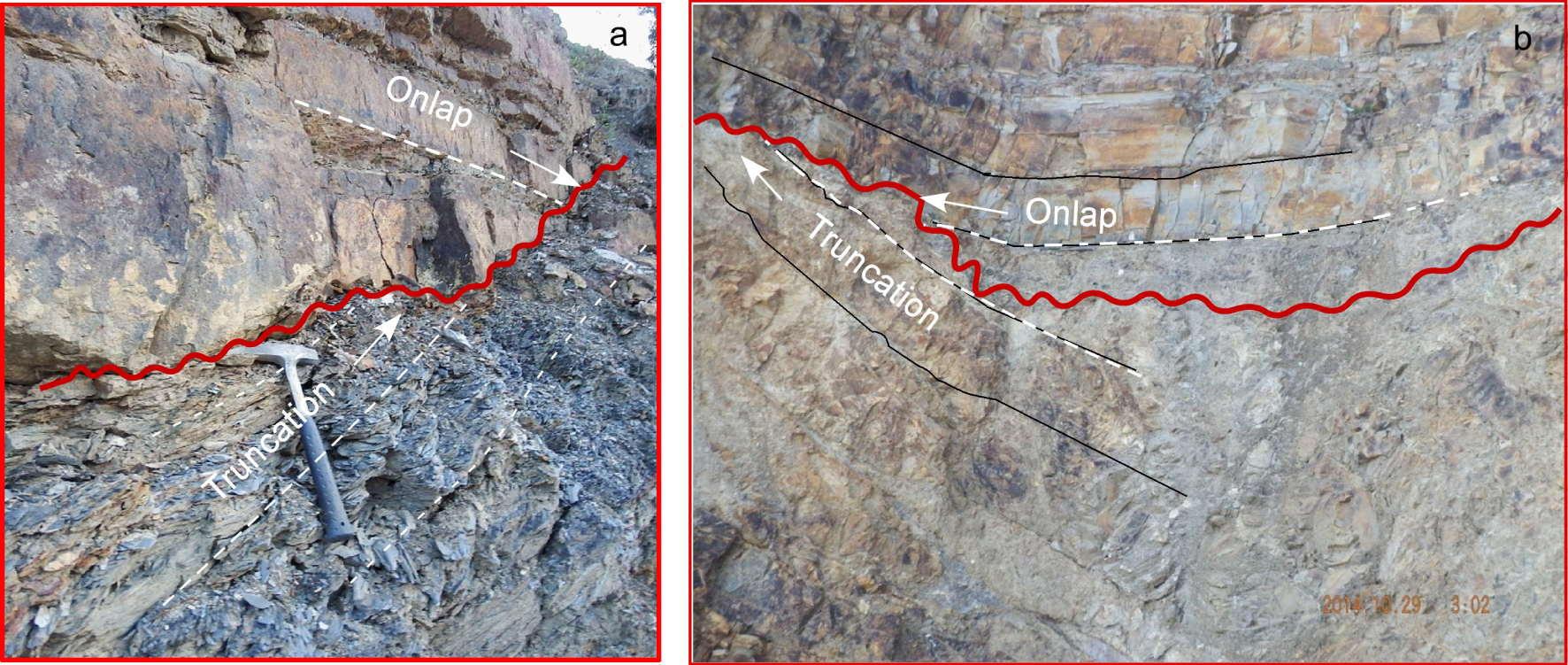

Unconformities identified in outcrops. Note the angularity observed between the units below and above the unconformities. (a) The late Albian–early Cenomanian boundary along the Villa de Leyva–Cucaita road; (b) the Cenomanian Simijaca/Frontera Fm south of the Susa town.

Based on paleogeographic synthesis and regional observations, Macellari [1988] and Morales et al. [1958] reported comparable time gaps in the Andean realm and in the MMV, respectively. Apatites and zircons dated from granites of the Central Cordillera in Colombia [Villagómez 2010], and K–Ar ages from igneous rocks from the Cordillera de la Costa, Curaçao and “Isla de los Hermanos” [Santamaria and Schubert 1974] indicate Cenomanian igneous activity related to tectonic events [Cooney and Lorente 2009].

These observations led us to analyze the Cretaceous sedimentary record of the MMV and WEC, based on seismic reflection profiles and information from wells in the MMV, and on geological field sections in the WEC. These results allowed the identification of regional unconformities of Upper Jurassic to Eocene age.

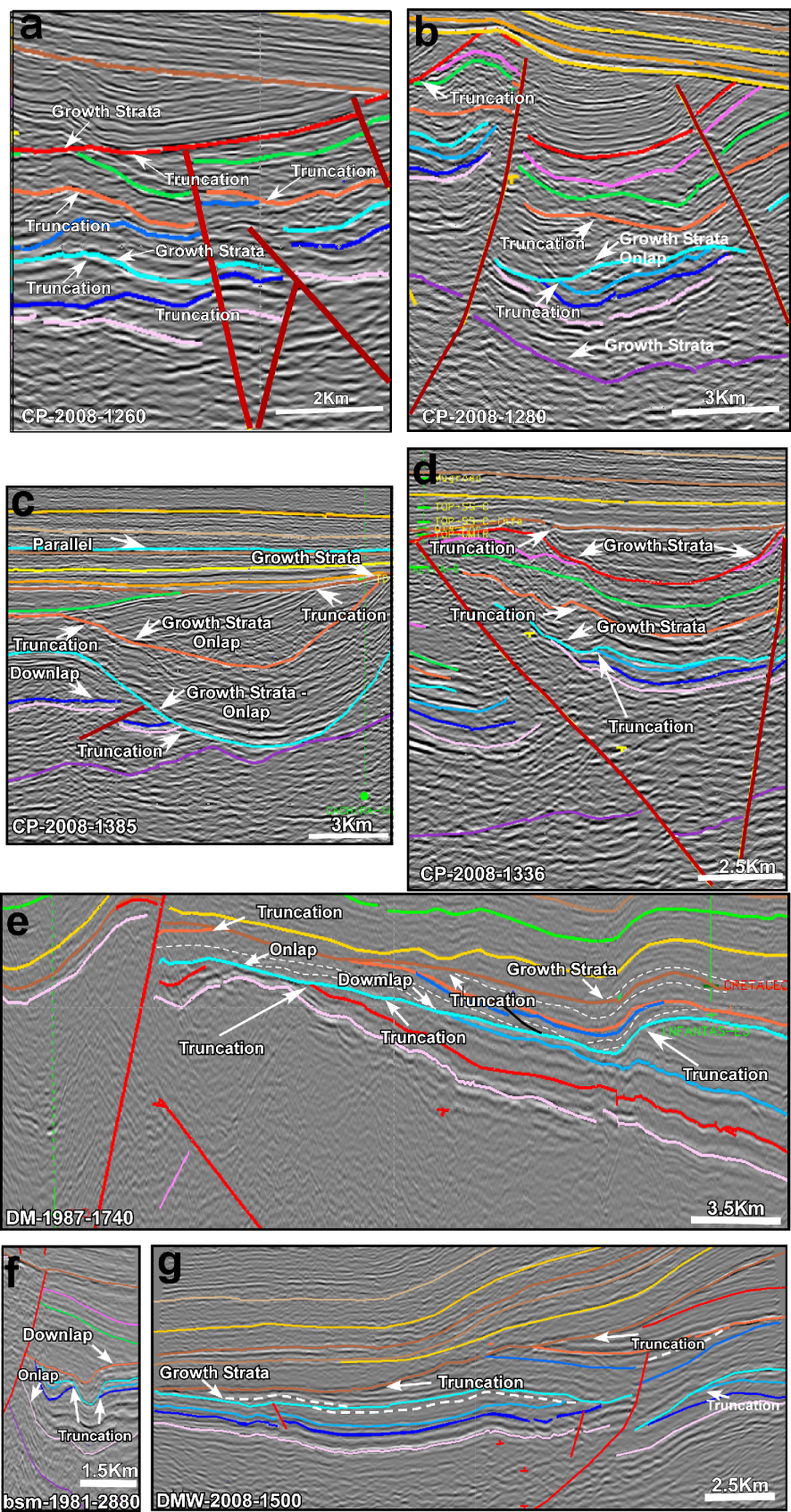

Seismic reflection patterns allowing the identification of unconformities. Truncation and growth strata are shown on different examples of a seismic section. From base to top: SU1 in pink (Upper Jurassic unconformity); SU2 in light blue (Aptian unconformity); SU3 in orange (Cenomanian unconformity); SU4 in red (Campanian unconformity); SU5 in brown (Eocene unconformity or younger).

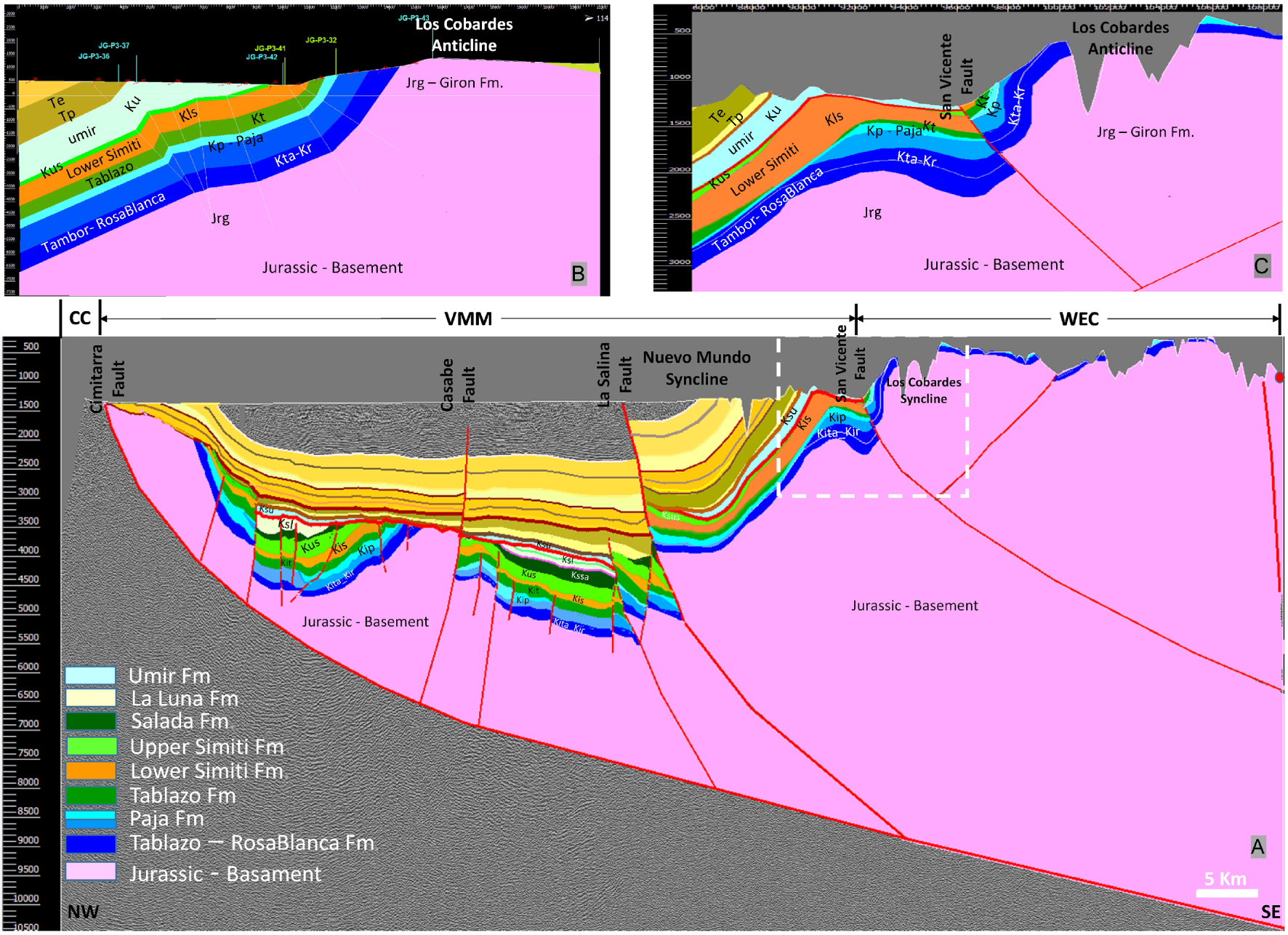

Structurally interpreted section in TWT, in the north of the MMV and WEC (location on Figure 1). (A) The seismic profile corresponds to the regional line ANH-TA-2006-4A1, (B) corresponds to structural seismic profile from structural and lithological information collected in the field and from geological maps; (C) from seismic data. Note the different interpretation from field data and using seismic reflection.

2. Geological setting

The tectonic evolution of northwestern South American active margin is mainly controlled by the interaction between the Nazca, Caribbean and South American plates. The latter is subjected to subduction processes that provoked the accretion of oceanic terranes (e.g. Western Cordillera (WC)) against the western margin of Colombia [Duque-Caro 1990]. These accretionary events are assumed to be responsible for compressional tectonic events, especially the tectonic inversion of extensional basins during Late Cretaceous and late Miocene times [Colmenares and Zoback 2003; Cortés et al. 2005; Gómez et al. 2003; Horton et al. 2010a,b; Moreno et al. 2011; Parra 2008; Parra et al. 2009; Sassi et al. 2007].

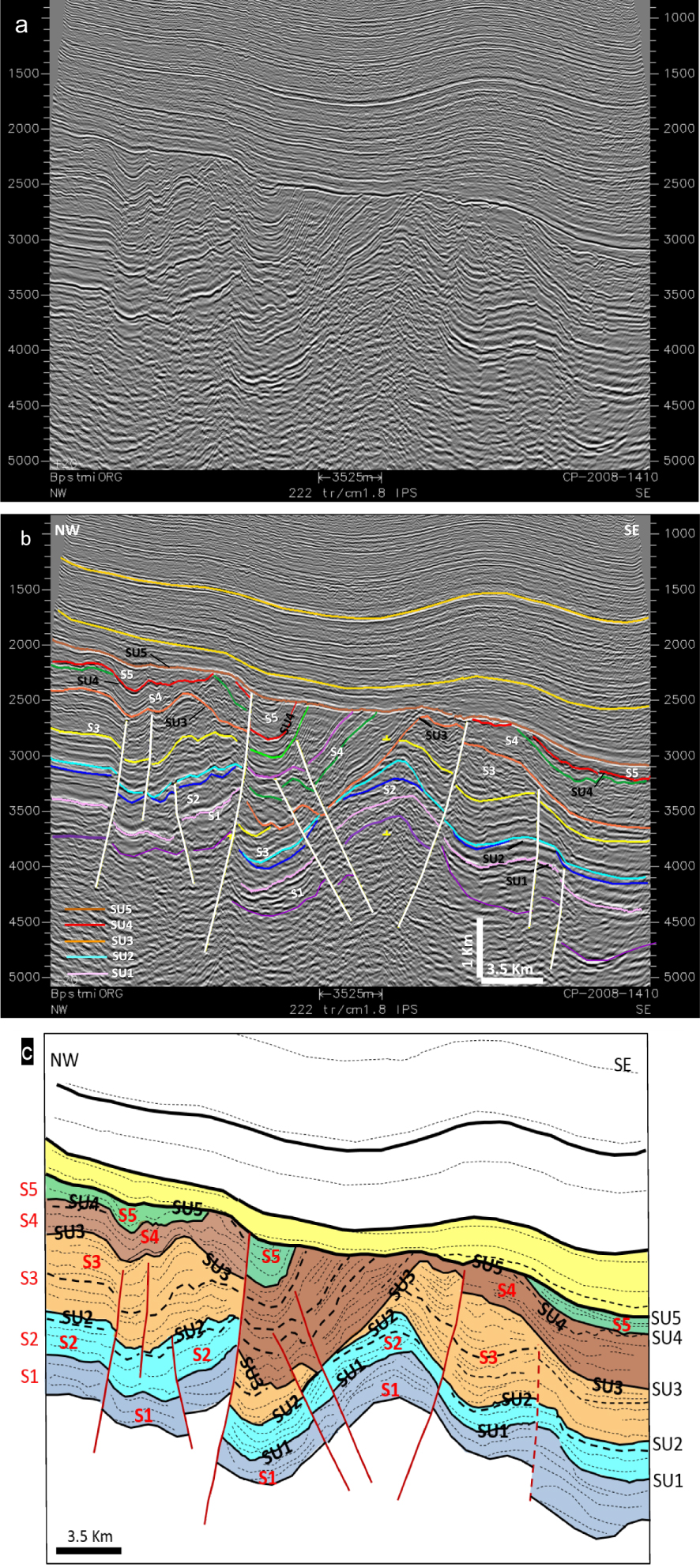

Seismic reflection profile CP-2008-1410, orientated NW–SE, in the northern MMV (location on Figure 1). (a) Seismic section; (b) Seismic interpretation; (c) Sketch illustrating the seismic sequence (S1 to S5), and unconformities or non-depositional surfaces (SU1 to SU5) from Barremian to Paleocene times.

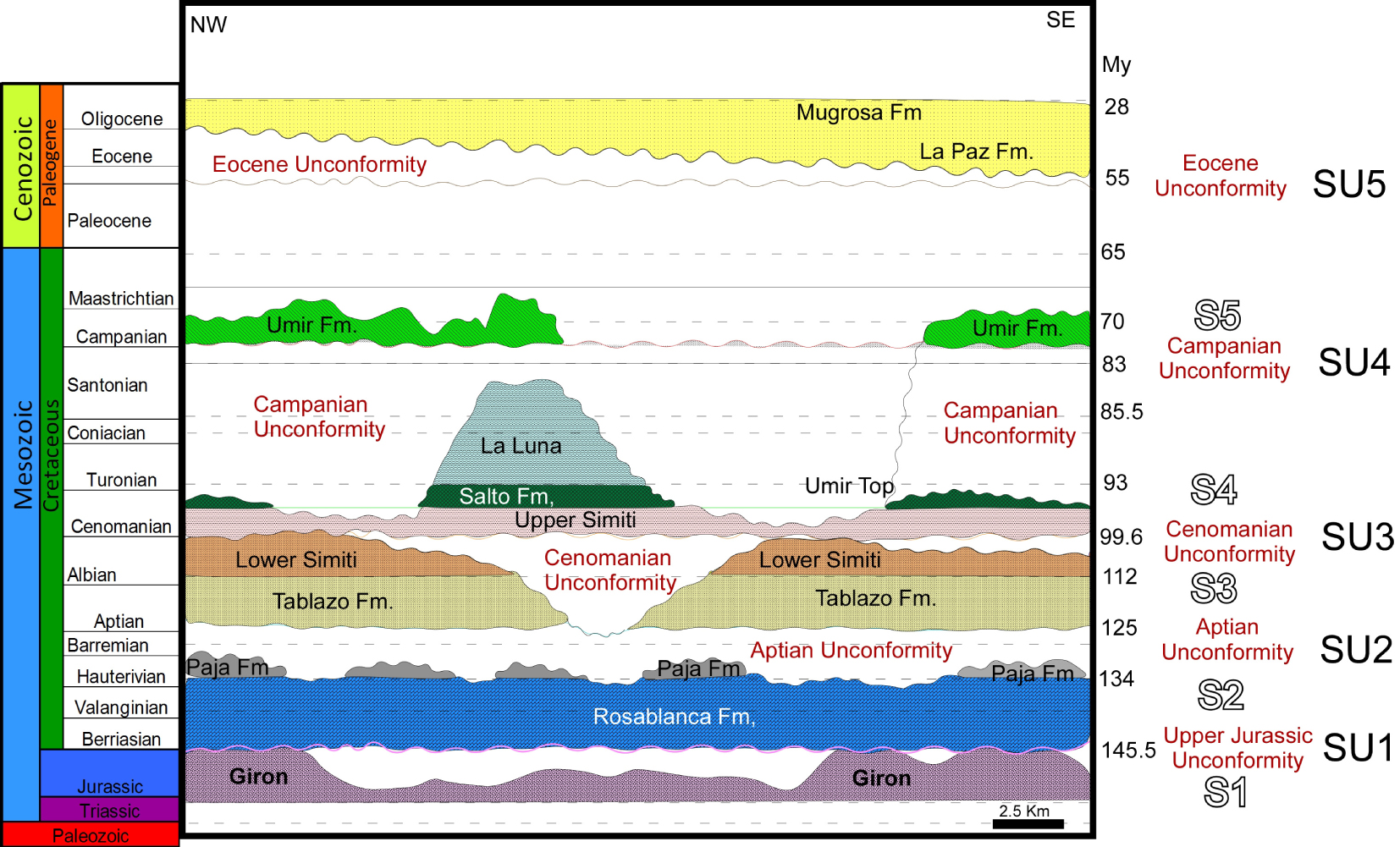

Chronostratigraphic chart after seismic stratigraphic interpretation (Figure 6) using Wheeler diagram. The Chart showing the unconformities for Aptian (SU2), Cenomanian (SU3) and Campanian (SU4); and also for Upper Jurassic (SU1), Eocene and Oligocene (SU5) that bounded stratigraphic sequences from S1 to S5.

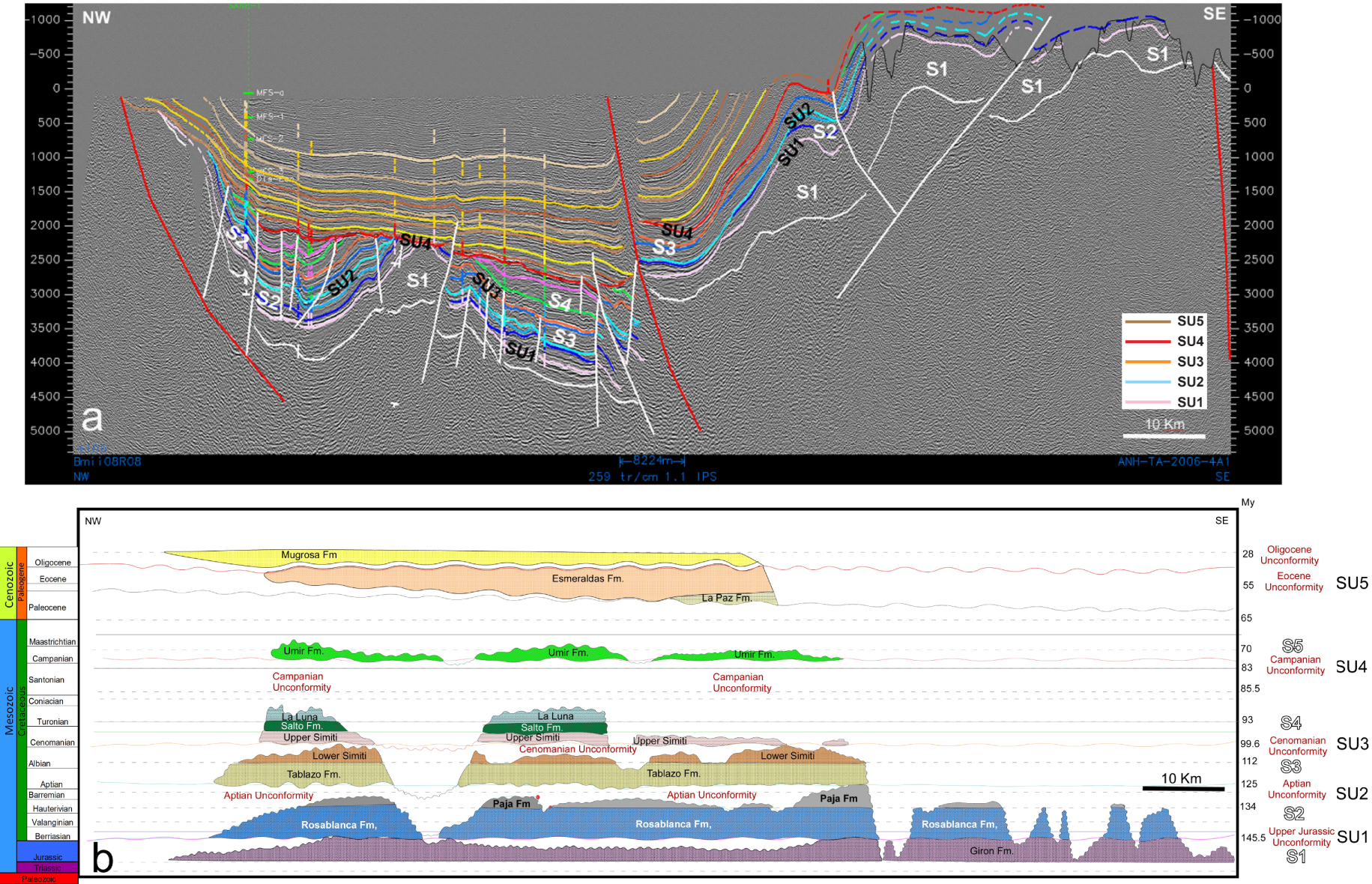

Chronostratigraphic chart (8b) of the 147 km long profile ANH-1A-2006-4A1 (8a location on Figure 1). This section covers the Central Cordillera to the WEC. Stratigraphic time-scale on the left, numerical ages on the right. Identified sequences are named S1 to S5 and unconformities labeled SU1 to SU5 (right).

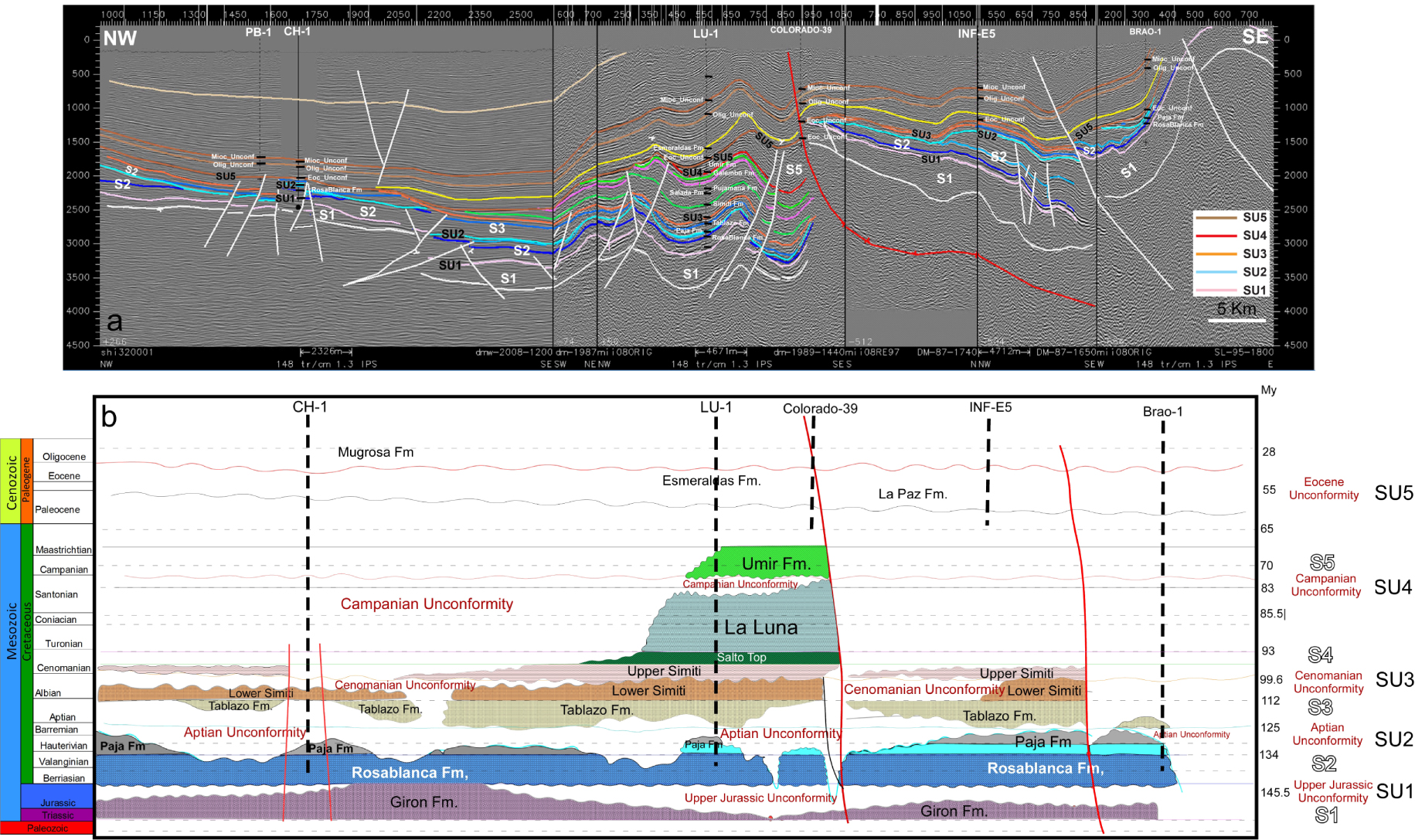

(a) Composed seismic profile (dmw-2008-1200, dm-1987-1320, dm-1989-1440, DM-1987-1740, DM-1987-1650, SL-95-1800; (b) Chronostratigraphic chart for the section above (location on Figure 1). The stage age is shown on the scale at the left and the age in Ma at right. Five sequences (S1 to S5) are limited by five unconformities (SU1 to SU5). Three wells crosscut the Cretaceous sequence: the most complete succession has been found in the LU-1 well.

The Andes of Colombia comprise three cordilleras (Western, Central and Eastern Cordilleras), separated by two inter-Andean valleys (Cauca Valley and Magdalena Valley). The MMV basin is 560 km long and 80 km wide, and is separated from the CC to the west by east-facing thrust faults and from the EC to the east by a west-vergent thrust belt [Butler and Schamel 1988; Gómez et al. 2003; Namson et al. 1994].

The thick Mesozoic sequences were deposited in the MMV in an extensional context [Clavijo et al. 2008; Etayo Serna et al. 1969; Sarmiento 2001]. Deposition of marine sediments ceased due to the accretion of oceanic terranes of Western Cordillera (WC) [Aspden et al. 1987], which created a Paleogene foreland basin in the MMV [Cooper et al. 1995]. Compressional deformation associated with the oblique accretion of the present-day WC, which produced shortening and uplift of the Central Cordillera [Cooper et al. 1995; Gomez et al. 2005], is believed to not have occurred before the Campanian.

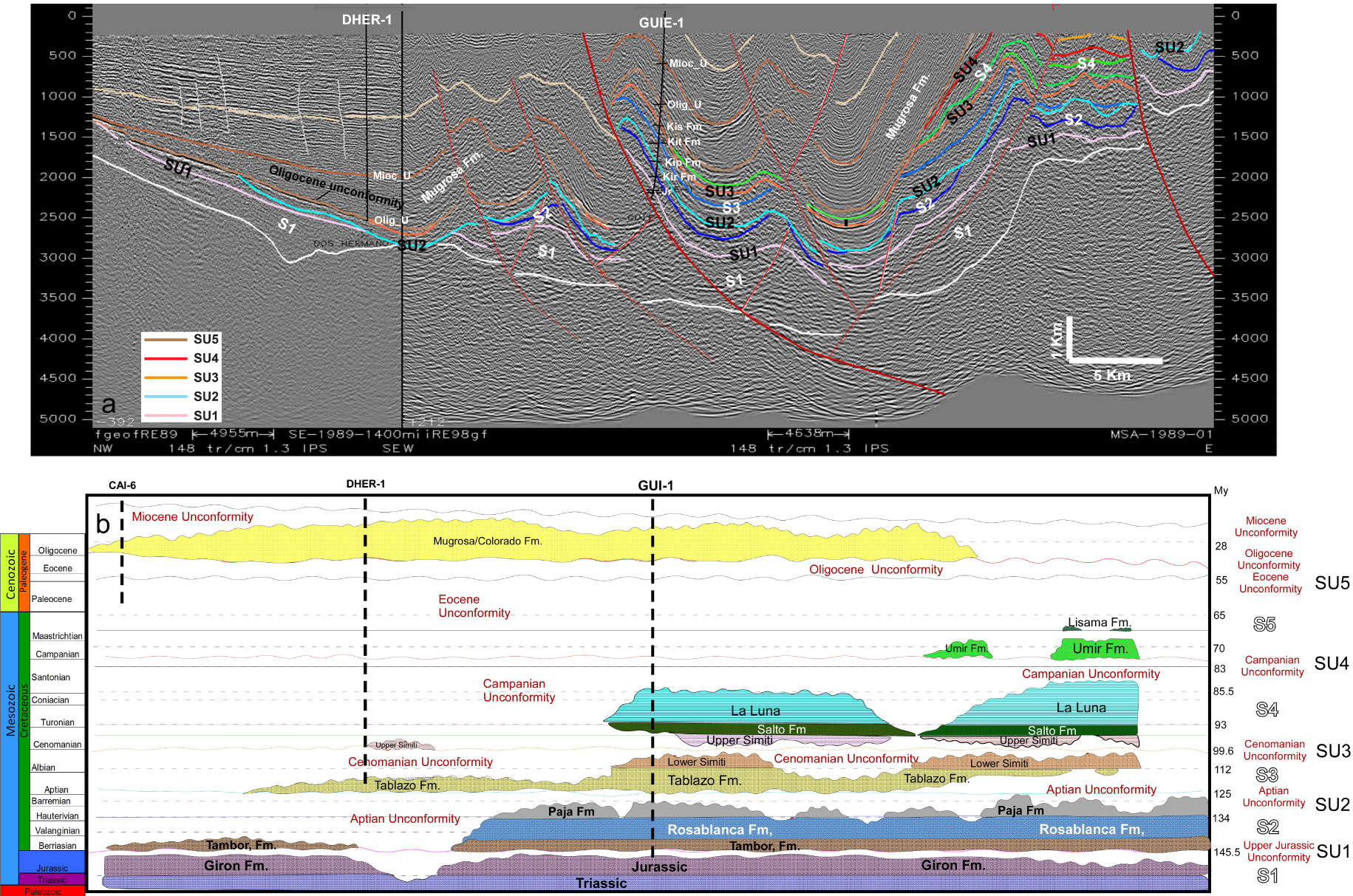

Seismic section and chronostratigraphic chart for the composite section SE-1989-1400 and MSA-1989-01 (location on Figure 1). Stratigraphic and numerical ages are shown on the left and right hand, respectively. The five identified sequences (S1 to S5) are bounded by five unconformities (SU1 to SU5)—hiatuses are in white.

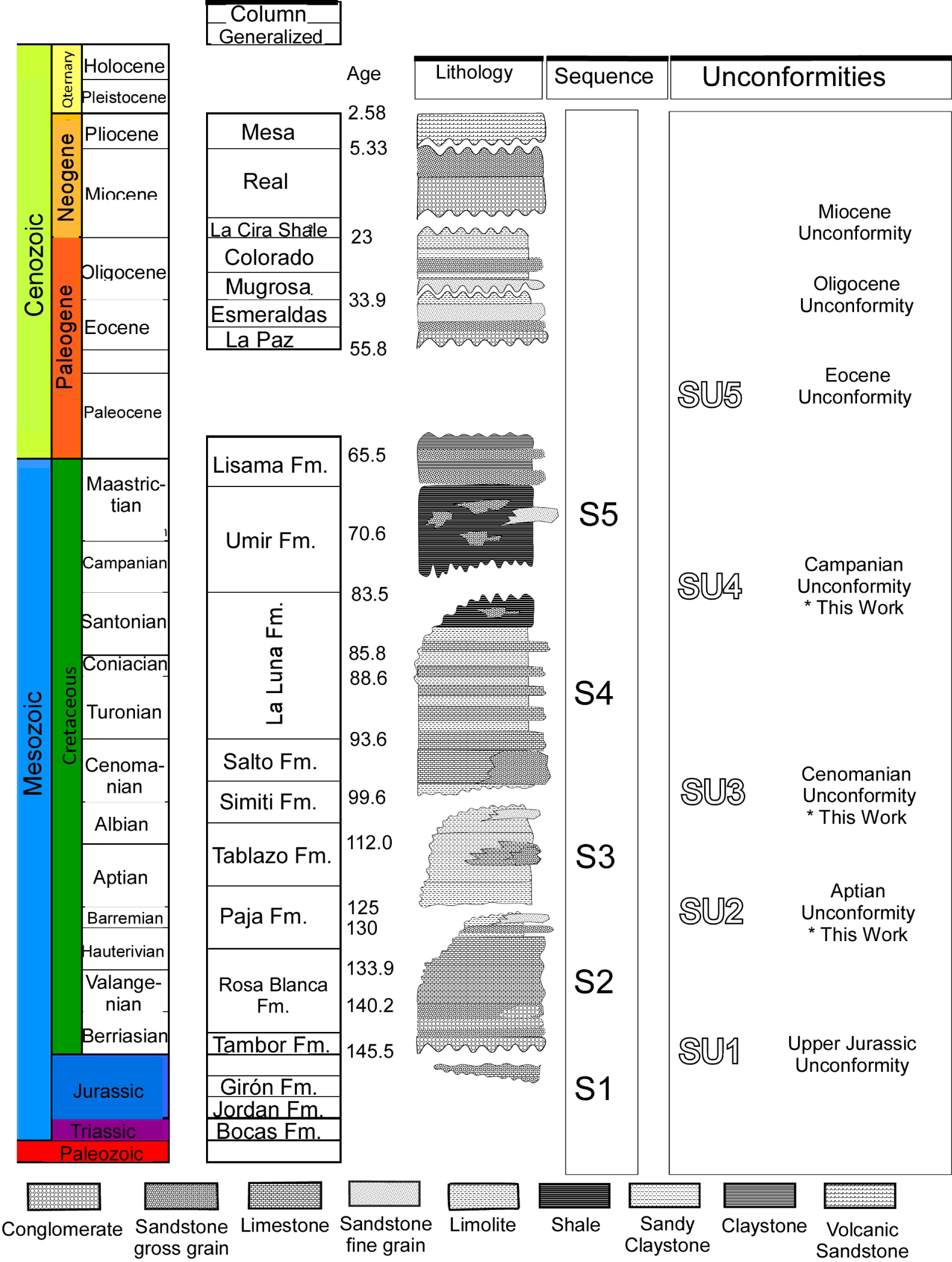

General stratigraphic column proposed for the MMV and WEC, showing identified unconformities (SU1 to SU5) and sequences (S1 to S5).

Stratigraphic column of the LU-1 well reconstructed from well log description and gamma ray (left). Chronostratigraphic chart for the seismic profile, showing the sequences, unconformities and hiatuses, and the location of the LU-1 well (center).

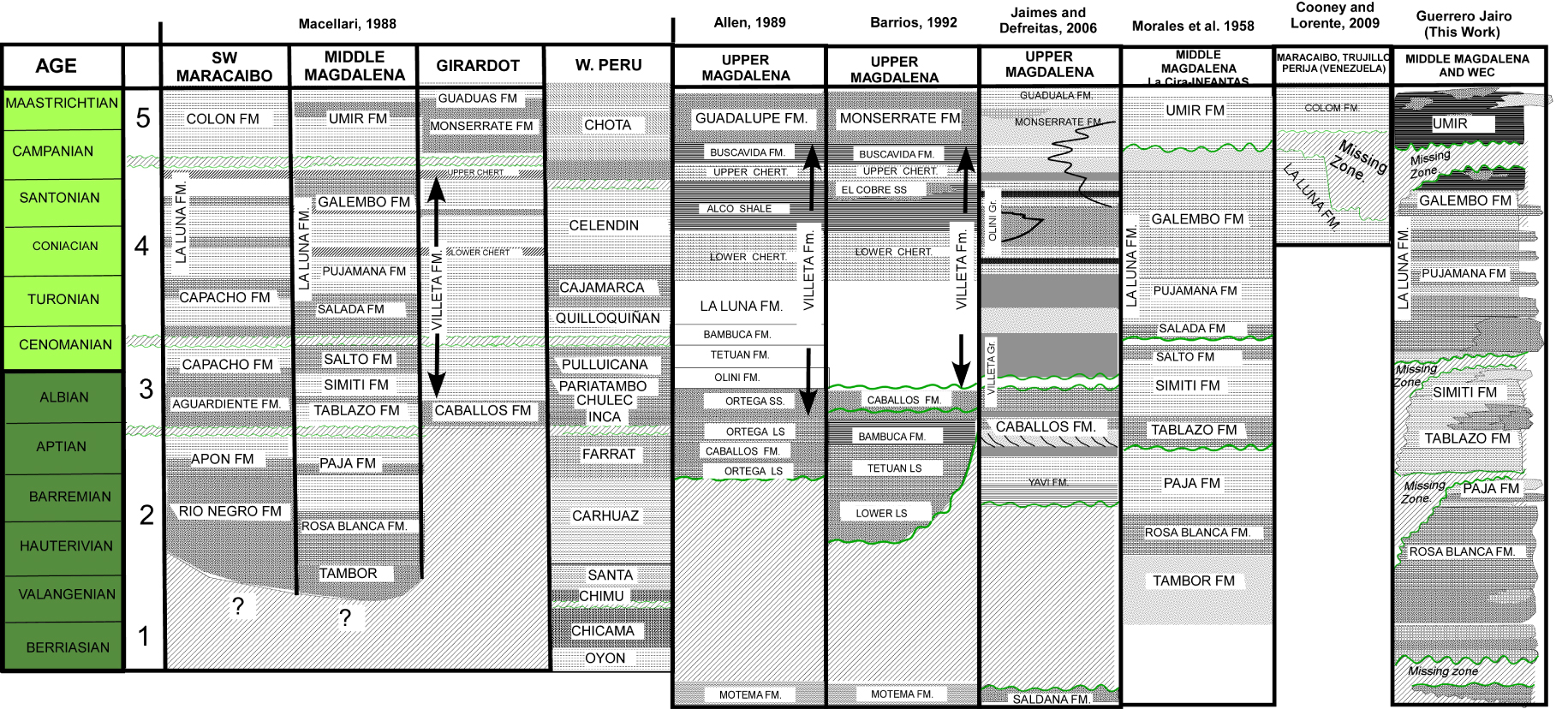

Stratigraphic chart, correlation and comparison between sections from different localities from Peru to Venezuela. Stratigraphic series are from Western South America [Macellari 1988], the Upper Magdalena Valley [Allen 1989; Barrio and Coffield 1992; Jaimesde and de Freitas 2006], the Middle Magdalena Valley [Morales et al. 1958] and western Venezuela Cooney and Lorente [2009], are compared with the column proposed in this work (right, Guerrero 2018).

3. Material and methods

The MMV and WEC areas are about 50,000 km2 wide. We used the biostratigraphic and sedimentological information from wells that crossed the whole Cretaceous sequence, shown in Figure 2. Structural and stratigraphic information on the WEC has been collected during fieldwork (Figure 3) or from published literature and geological maps [Acosta and Ulloa 2001; Fuquen and Osorno 2005; Renzoni et al. 1967; Rodríguez and Ulloa 1994].

Available seismic lines represent more than 50,000 km, of which selected lines are located in Figure 1. A detailed seismic interpretation was carried out, including the analysis and incorporation of well-logs, structural and stratigraphic information aimed at correlating seismic units and the construction of chronostratigraphic charts.

Reflector geometry, seismic expression and relation between strata and stratigraphic surfaces were essential elements to define sequences and their related bounding unconformities. This analysis, based on 2D and 3D seismic data and observations on outcrops (Figure 3a, b) considers the type of stratal terminations [Emery and Myers 1996; Ramsayer 1979]. Other terms have been introduced to define the architecture of seismic reflections [Mitchum 1977; Mitchum and Vail 1977], or to describe stacking patterns, surfaces and system tracts [Christie-Blick 1991; Posamentier and Vail 1988; Van Wagoner et al. 1988]. Figures 4a–g show truncations, growth strata, and unconformities sealing faults in the MMV and WEC, which are useful evidences to identify unconformities, erosion surfaces and tectonic–sedimentary events [Shaw et al. 2005].

4. Seismic interpretation of the Cretaceous series in the MMV and WEC

4.1. Structure of the MMV and WEC

Figure 5 shows a section from the CC to the WEC, crossing the MMV. The two interpretative structural sections from the WEC along the Rio Sogamoso (Figure 5, upper part), were built using field information and geological maps in the WEC (left), and seismic information in the MMV (right), which allowed detailed interpretation and identification of unconformities.

4.2. Cretaceous unconformities

The unconformities identified in the MMV Basin may be due to tectonic activity, sea-level fluctuations or both. Unfortunately, the scarce outcrops (Figure 3) and biostratigraphical information are usually not accurate enough to identify the missing stratigraphic rock sequence, except in the LU-1 well, which is exceptionally rich in ammonites [Etayo-Serna 2012] and in palynological data (as also in CAS-1 well). In the study area, five unconformities (SU1 to SU5) define the seismic sequences, among which the Upper Jurassic SU1 and the Late Cretaceous–Paleogene SU4 and SU5 have been known for a long time.

4.2.1. Unconformity SU1

This unconformity of Late Jurassic age may erode sequence S1 or even basement rocks (SU1, Figures 6–10). It is acknowledged as a regional unconformity that is locally angular, suggesting compressional deformation in the Late Jurassic [Pulido 1979a,b, 1980].

4.2.2. Unconformity SU2

The Aptian unconformity (SU2, Figures 4 and 6–10) deeply erodes sequence S2, as shown in Figures 6 and 7, and may remove part of the Rosablanca Formation (Fm) of Berriasian–Valanginian age (e.g. Figure 9), or even Jurassic deposits. Figures 4e and 9 show an angular truncation below SU2 in wells INF-E5 and LU-1, also evidenced by the ammonites described in the La Paja Fm [Etayo-Serna 2012]. Growth strata are other pieces of evidence of this unconformity (Figures 6 and 7). A few authors reported a comparable Aptian hiatus [Macellari 1988; Morales et al. 1958]. In the UMV, Barrio and Coffield [1992] and Allen [1989] reported an unconformity of Barremian–Aptian age.

4.2.3. Unconformity SU3

Within the Simití Fm of Cenomanian age (Figures 7–10), the SU3 unconformity erodes sequence S3 (Figures 7 and 8) and possibly reaches Jurassic rocks. Growth strata and onlap terminations are visible above, and angular truncation below, the SU3 surface (Figure 7). SU3 may encompass the early Cenomanian where the unconformity interpreted in seismic lines, is considered coeval with the regression that eroded partially or totally the Albian units (Tablazo–Lower Simiti). SU3 overlies fine-grained deposits, and is overlain by coarse to conglomeratic sandstones that mark the base of the early Cenomanian (Figures 3, and 6–10). SU3 locally eroded the Early Cretaceous sequence, leading locally to the disappearance of the SU1 and SU2.

Such a Cenomanian unconformity has been suggested in the MMV by Morales et al. [1958], while a hiatus is mentioned in Maracaibo, MMV and western Peru [Macellari 1988], and in the UMV [Jaimesde and de Freitas 2006]. SU3 is responsible for a significant erosion, which may have removed strata of Lower Cenomanian to Aptian age.

4.2.4. Unconformity SU4

The SU4 unconformity of Campanian age (Figures 7–10) underlies the Umir Fm or the Guadalupe Group. In the MMV, much of SU4 has been removed by the Eocene erosion (SU5, Figures 7 and 10). In Figures 7, 8 and 9, only patches of the S4 sequence can be observed to the east, near the surface, but S4 is widespread in other parts of the basin (e.g. Figure 10). Our analysis shows that the SU4 unconformity eroded deposits of S4 (early Campanian to Cenomanian), removing up to ≈1500 m of sediments (Figure 6). SU4 is the most relevant Cretaceous erosional event that was previously identified by Balkwill et al. [1995], Jaillard et al. [2000], Veloza et al. [2008] and Cooney and Lorente [2009], in Peru, Ecuador, Colombia and Venezuela. In the LU-1 and CAS-1 wells and in “Quebrada la Sorda”, SU4 is marked by the lack of the Dynogymnium zone, accompanied by a change in thickness, for example, between the La Luna and base of Umir Fm [ICP-Ecopetrol 2013] marked in seismic lines by truncations, growth strata or onlap (Figure 4). The top of this zone is marked by a change from mainly marine to mostly continental palynological assemblages at the base of Umir Formation.

4.2.5. Unconformity SU5

SU5 represents the well-known Eocene regional unconformity. It is easily identified in seismic profiles and is represented by angular truncations. SU5 eroded totally or partially older unconformities (Figures 7 and 10).

4.3. Seismic sequences

Discontinuity surfaces interpreted in seismic lines or by the analysis of seismic patterns as unconformities, or their correlative conformities (Figure 4), allowed the identification of seismic sequence boundaries. Five Cretaceous sequences bounded by five unconformities were identified in the MMV and some in the WEC, together with the wells and the few available biostratigraphic data.

Figure 6 shows the interpretation of a NE–SW trending seismic line. The Cretaceous sequence exhibits a complex structural evolution, with several pre-Andean erosional unconformities. The stratigraphic sequences S1 to S5 defined by the unconformities SU1 to SU5, identified in some wells in the MMV (e.g. LU-1 well), allowed the seismic interpretation (Figures 6–13).

The identified unconformities are of Upper Jurassic (SU1), Aptian (SU2), Cenomanian (SU3), Campanian (SU4), and Eocene (SU5) age, respectively (Figures 6–13). The presence of these unconformities evidence that the Cretaceous history of the MMV and WEC Basin (Figures 6–9) is more complicated than previously thought, and suggests that tectonic deformation, reverse faulting, sedimentation and erosion repeatedly occurred during the Cretaceous in the MMV and WEC (Figures 4, 5 and 6). Faulting affecting different levels and sequences (S2, S3, S4) indicate tectonic events occurring during most of the Cretaceous (Figure 6). Incipient basin inversion possibly started as early as in Barremian–Aptian times and became more intensive through time and culminated with the Campanian and Eocene erosions.

4.3.1. S1 Sequence (Jurassic previous to 145 Ma)

The Jurassic S1 sequence (Girón Fm, Los Santos Fm, Arcabuco Fm) is shown in Figures 6, 8–11. In the MMV, no well crosscuts this sequence, but it crops out in the northern and central parts of the WEC (Los Cobardes and Arcabuco synclines).

4.3.2. S2 Sequence (Early Berriasian–Late Barremian)

The S2 sequence is bounded by the regional unconformity SU1 at the base and by SU2 at the top (Figures 6c and 11). It is composed of late Berriasian to late Barremian deposits and has been recognized in all the study area from north (Figure 6) to south. At that time, shallow marine facies migrated from east to west through time, the observed facies being deposited in deeper environments westward.

4.3.3. S3 Sequence (Early Aptian–Late Albian)

The S3 sequence, comprised between SU2 and SU3, exists in the entire study area (Figures 6–8 and 11). The SU3 surface partly or totally eroded the S3 sequence, which comprises the units deposited during the Early Aptian to Late Albian interval (Figures 7–8, and 11).

4.3.4. S4 Sequence (Early Cenomanian–Late Santonian)

The S4 sequence is defined between unconformities SU3 at the base and SU4 at the top (Figures 6–11) and includes all units deposited from early–middle Cenomanian to late Santonian times.

4.3.5. S5 Sequence (Campanian–Paleocene)

S5 sequence is limited by SU4 at the base and by the Eocene hiatus SU5 at the top (Figures 6–8 and 11). S5 is composed of all units deposited from early/middle Campanian to Paleocene. The base of this sequence presents a marked continental influence and records the first occurrence of the pollen Ulmoidipites krempii, associated with Spinizonocolpitesbaculatus and the dinoflagellates Andalusiella mauthei and A. complex. Its top is marked by the occurrence of the pollen Proteacidites dehanni.

5. Chronostratigraphic seismic interpretation

2D seismic lines, tied to wells, and the use of Wheeler diagrams [Wheeler 1958] allowed the construction of chronostratigraphic charts to understand spatiotemporal relationships of strata across the MMV and WEC. In seismic sequence stratigraphy, seismic reflectors are regarded as geological timelines, and are thus chronostratigraphic guides.

The constructed chronostratigraphic charts (Figures 7–9) show that sequence S1 to S5 and unconformities SU1 to SU5 were observed in all the interpreted sections in the study area. In Figure 6b, the unconformities cut down previous deposits expressing erosion. For example, SU3 locally removes the Albian–Aptian units (Lower Simiti and Tablazo fms, Figures 6 and 7). In Figure 7, the chronostratigraphic chart expresses the time gap related to unconformities.

SU1 produced a significant erosion, mainly in the central part of the section and SU2 affected the whole area, cutting part of the Barremian–early Aptian Paja Fm and reaching the late Hauterivian Rosablanca Fm. SU3 locally eroded the middle Aptian to early Cenomanian Lower Simití and Tablazo fms, and SU4 eroded part of the Campanian to late Cenomanian La Luna and Upper Simiti fms. Finally, the well-documented mid-Eocene unconformity (SU5) eroded the Campanian to Paleocene units Umir and Lisama fms (S5).

Figure 8a shows that the SU1 unconformity eroded sediments of the Jurassic sequence (probably Girón Fm). SU2 (Aptian) strongly eroded Hauterivian–early Aptian deposits and partially the Berriasian–Valanginian unit (Rosablanca Fm), leaving relicts of the lower La Paja Fm. SU2 eroded the S2 sequence, probably due to the early Aptian low sea-level period. SU3 eroded the Albian part of sequence S3, but also part of the Aptian–lower Albian Tablazo Fm. SU4 caused the erosion of early Cenomanian to late Santonian deposits. SU5 only preserved part of the Campanian units (relict of the deformed Umir Fm), removing units of Campanian to Early Paleocene age.

The NW–SE trending seismic section of Figure 9 shows the erosion of almost the whole Cretaceous sequence around the Brao-1 well and in its western part (CH-1 well). The CH-1, LU-1, Colorado-39 and Brao-1 wells tie the stratigraphy of seismic sequences, allowing the identification and analysis of the Cretaceous succession. The well LU-1 cuts almost the complete Cretaceous sequence and represents one of the best-documented section of the Cretaceous series in the MMV (Figure 9). The biostratigraphic information from the LU-1 well has been used to identify the unconformities, sequences and hiatuses. As a result of these data and of seismic interpretation, the chronostratigraphic chart reveals the time gaps of SU2 and SU4, of Aptian and Campanian age, respectively (Figure 9b).

To the west of Figure 10, the erosion removed much of the Cretaceous sequence, whereas to the east, late Cenomanian to Maastrichtian units (Upper Simití to Umir fms) are partially preserved. SU1 (Late Jurassic) locally eroded the Jurassic unit (Girón Fm). SU2 (Aptian) eroded almost the whole S2 sequence (Berriasian–Barremian) with only part of the early Berriasian being preserved to the west. However, sequence S2 is better preserved around the Guie-1 well. The SU5 unconformity (Eocene) eroded sequence S5 in most parts, and the Oligocene unconformity removed Eocene deposits and the S5 sequence.

6. New synthetic stratigraphic column

The field observations in the MMV, together with information from seismic reflection, wells from the MMV and WEC and the chronostratigraphic seismic analysis, allowed the construction of composite stratigraphic column. Figure 11 shows the identified unconformities SU1 to SU5, and the related eroded and preserved Sequence S1 to S5. Figure 12 synthesizes the unconformities identified in the LU-1 well based on biostratigraphical description (Figure 12 left), chronostratigraphic chart and the generalized stratigraphic column [Guerrero 2018].

7. Discussion

This work defined and identified five sequences S1 to S5 and five unconformities SU1 to SU5 (Figures 6–12). Guerrero [2002] divided the Cretaceous series of Colombia based on regional sedimentary discontinuities corresponding mainly to transgressive and regressive surfaces. He recognized second-order regressive surfaces in the early–late Hauterivian, late Aptian–early Albian, late Albian–Cenomanian, Santonian–Campanian and Campanian–Maastrichtian boundaries, which represent changes from deep to shallow depositional environment. The Albian–Cenomanian and Santonian–Campanian regressions correlate with our SU3 and SU4, respectively. Haq et al. [1987] mentioned a significant sea-level fall in the Early Aptian that can account for at least part of the SU2 unconformity. However, seismic interpretation and chronostratigraphic chart analysis suggest that in addition to eustatic variations, the tectonic activity could have played a role, since Cretaceous unconformities sealed the deformed sedimentary sequences [Guerrero 2018].

Other authors have mentioned the existence of gaps, or identified Cretaceous regional sedimentary discontinuities, in Andean basins [Cooney and Lorente 2009; Guerrero 2002; Haq et al. 1987; Jaillard et al. 2000; Jaimesde and de Freitas 2006; Macellari 1988; Mattson 1984; Pindell and Tabbut 1995; Patarrollo 2009; Ramos and Alemán 2000; Rollon and Numpaque 1997; Van der Wiel and Andriessen 1991]. Figure 13 shows a comparison between the hiatuses and unconformities established in the present work with those reported by other authors.

In northwestern South America, Macellari [1988] identified three sequence boundaries of late Aptian, middle Cenomanian and middle Campanian age, respectively. In Peru, Macellari [1988] identified a Valanginian sequence boundary and ascribed the Late Cretaceous unconformity to the Santonian–Campanian boundary. However, the Valanginian unconformity of Peru does not appear in our analysis, while our Berriasian unconformity has not been recognized by Macellari [1988] in Peru.

In the UMV, Allen [1989] identified an unconformity of Barremian–Aptian age. In the same area, Barrio and Coffield [1992] determined a diachronic Barremian–Aptian unconformity and a late Albian unconformity that eroded the Caballos Fm (Figure 13). Based on biostratigraphy and seismic interpretation, Jaimesde and de Freitas [2006] recognized internal deformation and a late Albian–Cenomanian unconformity in the Villeta Fm of the UMV (Figure 13). In the MMV, Morales et al. [1958] identified unconformities of early Aptian age (between La Paja and Tablazo Fms), in the middle Cenomanian (contact Salto-Salada fms), and in the Campanian (boundary La Luna–Umir fms). In western Venezuela, Cooney and Lorente [2009] proposed a Campanian, time-transgressive erosion at the top of La Luna Fm. This event would correspond to our SU4 [Guerrero 2018].

Jaillard and Soler [1996] and Jaillard et al. [2000] recognized four Cretaceous tectonic events. The first one at ∼100 Ma is coeval with an abrupt acceleration of the plates around the world and with the opening of the Atlantic Ocean at equatorial latitudes. The second event at 100–95 Ma (late Albian–early Cenomanian), coincided with a slowdown of the convergence rate. A Santonian event (≈85 Ma) coincides with a decrease in the convergence velocity. Finally, in the mid-Campanian (≈80 Ma) a major tectonic event is coincident with the plate velocity stabilization in the Andean zone. Jaillard et al. [2000] indicated that the change in the convergence direction at 60–50 Ma might be responsible for the significant tectonic event recorded in the Andean margin in the late Paleocene [Jaillard and Soler 1996].

All the authors cited above recognized erosions, non-depositional surfaces, surface boundaries, or unconformities during the Cretaceous. Some authors explained these events by sea-level changes or tectonic events. The origin of these unconformities could be eustatic, tectonic, or both, but this is not part of the discussion in this paper.

8. Conclusions

Our analysis allowed the identification of five sequence S1 to S5 limited by five unconformities SU1 to SU5, of which three are new ones. These newly identified unconformities are dated at the Aptian ( ∼125 Ma; SU2); at the Cenomanian ( ∼100 Ma; SU3), and in the Campanian ( ∼80 Ma; SU4).

Based on this study, a generalized composite stratigraphic column of the MMV and WEC is proposed, highlighting the importance of local or regional hiatuses. These structural and stratigraphic interpretations reveal a complex sedimentary and tectonic evolution of the MMV and WEC basins during the Cretaceous.

The analysis suggests that basin inversion possibly started earlier than previously proposed by Cooper et al. [1995], Restrepo-Paceetal [2004], Cortés et al. [2005], Gomez et al. [2005], Moretti et al. [2010] and Parra et al. [2012]. The presence of faults sealed by unconformities, folds related to faulting, truncation, deformation and growth strata are evidences that deformation began before the Late Cretaceous, possibly as early as during the Barremian–Aptian (below unconformity SU2).

The unconformities identified in this work are consistent with the early tectonic phases identified in Peru and Ecuador [Jaillard et al. 2000], in the Middle Magdalena Valley [Morales et al. 1958], in the Upper Magdalena Valley [Allen 1989; Barrio and Coffield 1992; Jaimesde and de Freitas 2006] and in western Venezuela [Cooney and Lorente 2009].

These comparisons allow proposing that deformation and erosional events occurred around the Jurassic–Cretaceous, Barremian–Aptian, Albian–Cenomanian, Santonian–Campanian and Paleocene–Eocene boundaries [Guerrero 2018].

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Université Grenoble Alpes (France) and Universidad Nacional de Colombia (Colombia) for providing economic resources and for laboratory support, the Empresa Colombiana de Petroleos (Ecopetrol) for providing seismic and well data, to the geologist and friend Alvaro Vargas, for his help in field work and for critical discussion during several field trips. The result presented here are part of the PhD thesis of Guerrero [2018].

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0