1. Introduction

Created in 1921, the Bureau Central Sismologique Français (BCSF) is responsible for the acquisition, analysis, and dissemination of information on earthquakes in France. For events of local magnitude larger than 3.5, detected by the Réseau national de surveillance sismique (RéNaSS) and/or the Laboratoire de détection géophysique (LDG) of the Commissariat à l’Énergie Atomique et aux Énergies Alternatives (CEA), the BCSF initiates a macroseismic study to report the damage caused by the earthquake. Recently the BCSF and the RéNaSS have merged into a single national seismological observation service.

In the northwestern (NW) part of France, presumably because of a low-to-moderate seismic hazard, permanent seismic networks at local scale have been sparse for decades. Most of the data recorded over the last 100 years, and thus the knowledge of natural seismicity, comes from the CEA and BCSF-RéNaSS. For the last 10 years, with the national project Résif-Epos (Réseau sismologique et géodésique français), the Observatoire des sciences de l’univers Nantes-Atlantique (OSUNA) is in charge of the deployment of the NW component of a dense, modern, and high-quality broadband seismic network, unprecedented in this region. The situation slightly differs in the southeast part of this region, since the Auvergne through the Observatoire de Physique du Globe de Clermont-Ferrand (OPGC) has a long history of seismic monitoring. The OPGC, member of Résif-Epos, is then in charge of all seismic stations located in the central part of France.

In the framework of the 100th anniversary of the BCSF, we review in this paper the characteristics of the seismicity in the northwestern quarter of metropolitan France, and we discuss the possible origins for such intraplate earthquakes. The considered region is wide and comprises the Armorican and Central massifs and a part of two sedimentary zones, the Aquitaine basin in the southwest and Paris basin in the northeast. This choice is consistent with the apparent continuity of seismicity from the Armorican massif to the southeast, although the two regions do not have the same seismic coverage over the ages. The seismic network in Auvergne has been denser than the rest of the region for many years. Hence, in order to quantify the impact of varying coverage over time, statistics are presented for the western sub-region (longitudes between 6° W and 2° E).

After a geological and tectonic review (Section 2), we detail the seismicity features using both historical and instrumental data (Section 3). We show in the same section that the magnitude of completeness can be decreased below 1 by taking advantage of a much denser network and with sophisticated detection/discrimination and event location methods. Finally, possible origins of seismicity and thus the potential triggering phenomena are reviewed and discussed in Section 4.

2. A polyphased geological setting

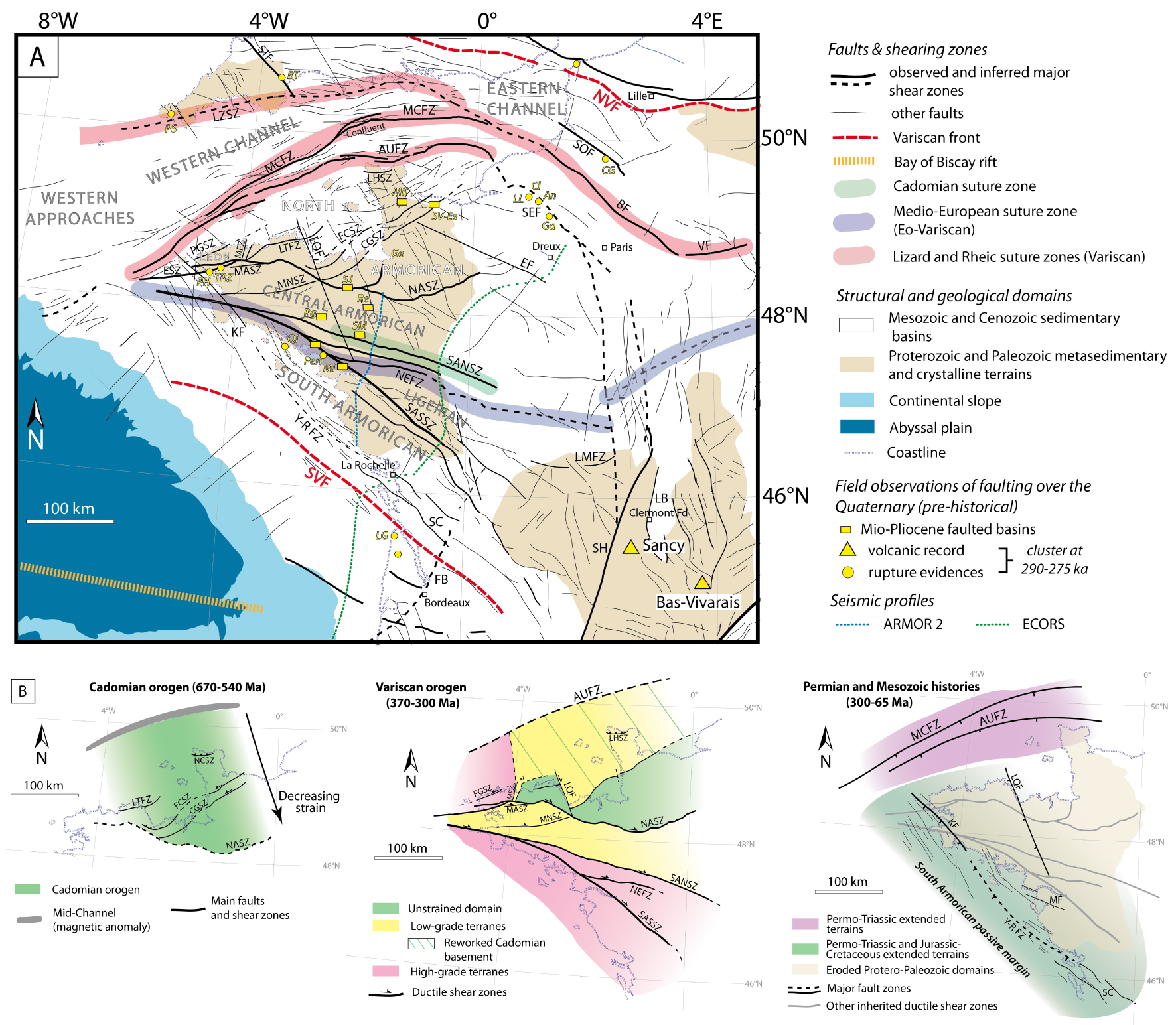

The intraplate seismicity currently recorded in the western part of France typically occurs in a polyphased structural context resulting from two successive major orogens: Cadomian (650–540 Ma) and Variscan (370–300 Ma). The associated structures have been eroded and exhumed and followed by more localized extensional (Meso-Cenozoic) and compressional (Cenozoic) events. Discussing the seismicity pattern in Western France requires first reviewing the regional structural context in order to quantify the inheritance potential, with emphasis on crustal-scale discontinuities that may be interpreted as seismically active faults. A strong structural inheritance may also influence the distribution of earthquakes although the triggering phenomenon may not be primarily due to active tectonics such as fault destabilization by normal stress unloading of natural [e.g. Sue et al. 2002], and/or anthropic [e.g. Cornou et al. 2021] origins. The synthetic geological map presented in Figure 1A is compiled from numerous in situ observations and fault data, including Quaternary structures [yellow symbols, Van Vliet-Lanoë et al. 2002; Baize et al. 2003].

(A) Compilation of major surface faults in Western France related to their origin (see details in the text). (B) Spatial extent of major tectonic phases and their associated structures in Western France, namely (1) the Cadomian and Variscan orogenic belts and (2) Permo-Mesozoic fault/basin patterns (The Variscan sketch map is modified from Le Gall et al. [2021]. Structures (in black). AUFZ: Aurigny–Ushant Fault Zone; BF: Bray Fault; CGSZ: Cancale-Granville Shear Zone; EF: Senonche-Eure Fault; ESZ: Elorn Shear Zone; FB: Bordeaux Fault; FCSZ: La Fresnaye-Coutances Shear Zone; KF: Kerforne Fault; LB: Limagne Basin, LHSZ: La Hague Shear Zone; LMFZ: La Marche Fault Zone; LQF: Le Quessoy Fault; LZFZ: Lizard Fault Zone; LTSZ: Locquemeau-Tregor Shear Zone; MASZ: Monts d’Arrée Shear Zone; MCFZ: Mid-Channel Fault Zone; MF: Machecoul Fault; MNSZ: Montagnes Noires Shear Zone; NCSZ: North Cotentin Shear Zone; NEFZ: Nort-sur-Erdre Fault Zone; NASZ; North Armorican Shear Zone; SANSZ: South Armorican Northern Shear Zone; SASSZ: South Armorican Southern Shear Zone; NVF/SVF: Northern/Southern Variscan Fronts; PGSZ: Porspoder-Guisseny Shear Zone; SC: Saintes-Cognac graben; SEF: Seine Fault; SH: Sillon Houiller; SOF: Somme Fault; STF: Sticklepath Fault; VF: Vittel Fault; Y-R FZ: Yeu-Ré Fault Zone. Sites (in yellow). LG: Le Gurp; Mi: Missilac basin; Pen: Pénestin; Qi: Quiberon; PH: Pen Hat; TRZ: TrezRouz; Rg: Réguigny; SM: St-Malo-de-Phily; Re: Rennes basin; SJ: St-Jouan; SV-Es: St-Vigor Esquay; Mil: Millières; Ge: Genêts; LL: La Londe; Cl: Cléon; An: Anneville; GA: La-Garenne-de-Andelys; CG: Cagny Epinette; Sa: Sangatte; PS: Prah Sands; BT: Beauvais-Tracey.

2.1. The Protero-Paleozoic basement

The present-day structural organization of the Armorican massif is a juxtaposition of three main domains: North (NAD), Central (CAD), and South (SAD); representing the deeply eroded root zones of the Cadomian and Variscan orogens (Figure 1A). These infra/supra-crustal terranes are bounded by crustal-scale discontinuities, mostly Variscan in age, which display specific tectono-metamorphic patterns with very little structural overprint [Ballèvre et al. 2009].

2.1.1. The Cadomian orogenic system (650–540 Ma)

The Cadomian orogenic system took place during the late Proterozoic to early Cambrian (650–540 Ma, Figure 1B; [Dupret et al. 1990]) and initiated as a large subduction-related orogen on the northern and active paleomargin of the Gondwana [Chantraine et al. 2001]. Discrete remnants of this orogen are still preserved in the NAD as sub-units separated by three main ductile shear zones extending in the Trégor and Cotentin peninsulas, i.e., the Locquemeau-Trégor (LTSZ), La Fresnaye-Coutances (FCSZ), and Cancale-Granville (CGSZ) structures (Figures 1A and B). Together, they form a >200 km wide crustal thrust wedge directed to the SW and possibly limited to the north by a suture zone currently marked by the Mid-Channel magnetic anomaly [Lefort and Segoufin 1978]. The frontal part of the Cadomian orogenic wedge might occur in Brioverian series forming the CAD, south of the (Variscan) North Armorican Shear Zone (NASZ). For our purpose, the most interesting Cadomian discontinuities are: (i) the La Fresnaye (FCSZ) and Cancale (CGFZ) arcuate shear zones which display on ARMOR and SWAT 10 seismic reflection profiles a relatively steep dipping attitude (60° to the NW) before shallowing at depth along a 20 km deep basal sole thrust on top of the layered lower crust [Bois et al. 1994; Bitri et al. 2010], (ii) the steep Locquemeau-Trégor (LTSZ) and the northerly dipping La Hague (LHSZ) shear zones which might correlate laterally as both bounding to the south a similar plutonic unit and its Archaean relics.

2.1.2. The Variscan orogenic system (370–300 Ma)

The post-Cadomian evolution of the Armorican massif took place in a renewed geodynamical framework involving three continental lithospheric plates, i.e., Gondwana (South), Armorica (Central), and Avalonia (North), separated by two oceanic realms, i.e., the Mid-European (Galice) to the South and the Rheic to the North [Matte 1986]. The double-verging subduction process that operated beneath the Armorica microplate finally evolved into a long-lasted collision system in the time range 370–300 Ma. Only the southern part of the subduction/collision pattern (Gondwana/Armorica) is fully recorded in the SAD [Ballèvre et al. 2009] and expressed as early as 370 Ma by a crustal-scale thrust-nappe network gently dipping NNE-ward as shown in Figure S1 [Brun and Burg 1982; Bitri et al. 2010]. At a more mature collisional stage (330–315 Ma), the SAD thrust pattern was disrupted by a dense network of dextral ductile shear zones (North, SANSZ, and South, SASSZ, branches of the South Armorican Shear Zone, Nort-sur-Erdre, Chantonnay) forming the wedge-shaped South Armorican Shear Zone complex [Bitri et al. 2003]. Seismic tomography [Judenherc et al. 2002; Gaudot et al. 2021] and deep reflection profiles [Bitri et al. 2003, 2010] show that these structures are currently associated with strong seismic velocity gradients that are restricted to crustal depths for the SANSZ, but extend down to lithospheric depths for the SASSZ (Figure S1). As the result of the northerly migration of the collision-related deformation, the thick Paleozoic sedimentary pile in the CAD later experienced transpressional tectonics focalized along the Monts d’Arrée (MASZ), Montagnes Noires (MNSZ) and NASZ dextral shear zones [Figures 1A and B; Darboux and Le Gall 1988; Gumiaux et al. 2004]. At this stage, part of the Cadomian structural pattern occurring north of the La Fresnaye shear zone (FCSZ) was reworked in a southerly directed Variscan fold-and-thrust belt [Le Gall et al. 2021], the initial suture zone being reactivated as the Alderney–Ushant fault zone (AUFZ in Figure 1A). Lateral boundaries of the stable Cadomian block (south) were rejuvenated as submeridian transfer faults (Morlaix MFZ and Le Quessoye LQF structures). Further north, closure of the Rheic ocean north of the Mid-Channel faulted zone (MCFZ in Figure 1A) led to the obduction of the Lizard ophiolite northwards (LZSZ) over the Cornwall–Devon deformed terranes [e.g. Le Gall 1990; Shail and Leveridge 2009]. Late Variscan deformation expressed at c. 300 Ma by discrete sinistral shearing along the N70° E Porspoder-Guisseny structure (PGSZ) in the Leon metamorphic block (Figure 1A). The dextral rejuvenation of part of the regional strike-slip shear zones in Late Carboniferous times guided the emplacement of narrow coal-bearing basins along the SASZ (Quimper–Raz point) and the Chantonnay and Sables d’Olonnes faults. Important late-stage Variscan sinistral strike-slip discontinuities took place in the Massif Central, such as the Sillon Houiller and the La Marche Fault (Figure 1A). Late-stage exhumation of the Variscan terranes occurred along flat-lying detachment faults in the upper crust in relation with the emplacement of anatectic granites [Gapais et al. 2015]. At the end of the Variscan orogenic period, the Western France upper crust thus displayed a strong heterogeneity, assumed to have later exerted a profound structural and rheological control during Meso-Cenozoic events, and marked by (i) NW–SE collisional fabrics evidenced at the base of the crust [Pn anisotropy; Judenherc et al. 2002] and down to the lithospheric mantle [shear wave splitting; Bonnin et al. 2017]; (ii) metamorphic anisotropies mostly striking NW–SE in the present-day upper (and certainly lower) crust; (iii) crustal weakening along the regional-scale (NW–SE) shear zones and variously trending subsidiary structures; and (iv) 3D compositional heterogeneities due to the extensive syn-tectonic plutonic (granitic) complex emplaced at various stages in the dominantly meta-sedimentary upper crust.

2.2. The Mesozoic history

The crust was reactivated during the Mesozoic following different main stages. A first aborted rifting initiated during the Pangea breakup and the opening of the central Atlantic Ocean [Permo-triassic extension, e.g. Chadwick and Evans 1995; Faure 1995]. This resulted in the development of onshore and offshore basins associated with magmatism and regional-scale fault networks: to the North, the inherited MCFZ and AUFZ were reactivated as normal faults [Figure 1B; e.g. Bessin 2014]; to the West, NW–SE transverse faults (Kerforne-type, e.g. KF, LQF, in Figure 1B) were developing in response to a second episode of extension trending ENE–WSW [e.g. Chadwick and Evans 1995].

Renewed and conspicuous NE–SW trending extension occurred from the Late Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous associated with eastward continental rift propagation along the Bay of Biscay in connection with the opening of the North Atlantic Ocean (Figure 1B). The significant transtensional stretching and large thinning left a deep imprint in the Western France basement [e.g. Jammes et al. 2010]. The south Armorican shelf constituted a passive margin [Thinon et al. 2001]. A clear and sharp crustal strain gradient is expressed at the level of the Bay of Biscay slope whose trend appears to have been primarily guided by the bulk NW–SE anisotropy inherited from the Variscan system and the reactivation of major late-stage faults responsible for the basin geometry such as the Sillon Houiller/Toulouse discontinuity (Figure 1A). To the NW, the fault systems in the Western Approaches, the Western Channel (including the MCFZ) correspond to en échelon strike-slip faults which have reactivated Cadomian and Variscan structures [e.g. Bourillet et al. 2003].

During the Aptian–Albian period (125–100 Ma), oceanic breakup occurred in the Bay of Biscay, and mantle was exhumed at the end of the eastward propagating system due to extreme lithosphere thinning. The overall morphology of the Armorican–English Channel system was already acquired before the Cenomanian [Wyns et al. 2003]. The subsidence of the Armorican margin along the Bay of Biscay began in the Upper Cretaceous. Just before the onset of Cenozoic, a first regional phase of uplift occurred at 95–65 Ma (Laramian phase during the convergence at the Iberian–European plate boundary), accentuating the emersion of the Armorica, Cornwall, Weald, and Massif Central [Le Roy et al. 2011].

2.3. The Cenozoic history

Most of the inherited fault networks highlighted in the previous sections (Figure 1B) were reactivated, depending on their strike and the orientation of the regional stress field, during successive phases of extensions and compressions that occurred over the Cenozoic. The opening of the Northern Atlantic (53–24 Ma) led to the acceleration of the subsidence of the Armorican margin along the Bay of Biscay [Le Roy et al. 2011], and the Western Channel [Lericolais et al. 1996] with major fault activity along the MCFZ and in the southern UK [Vandycke and Bergerat 2001]. Onshore, the Armorican massif and Northern Cotentin continued to uplift, reactivating faults such as the Kerforne fault (KF). Then the Pyrenean phase (40–39 Ma) took place in a mostly NS compressive stress field [Thinon et al. 2001; Le Roy et al. 2011] with some major inversions, such as in the Isle of Wight, south UK [Vandycke and Bergerat 2001], and offshore among the Wessex basin [Chadwick 1993]. Afterward, the E–W trending extension that occurred in Western Europe during the Oligo-Miocene allowed the uplift of the Armorican massif and the reactivation of the KF [Raimbault et al. 2018], as other fault networks in the Western Channel and the Western Approaches [e.g. Le Roy et al. 2011]. In the northern part of the Massif Central, this extension led to the formation of the Limagne basin, bounded by N–S trending normal faults [Figure 1A, e.g. Bergerat 1987]. Later, from the upper Miocene, the stress field came progressively back to a meridian position [today ca N170° E in Western Europe; Heidbach et al. 2016] with the continuation of the plate convergence between Africa and Europe. Onshore, Brittany blocks were globally uplifted from the Oligo-Miocene to the early Zanclean (∼5 Ma), even along the Elorn shear zone [ESZ in Figure 1A; Darboux et al. 2010]. Successive uplift and subsidence episodes affected the western France during the Early Tortonian–Late Messinian (from 11 to 6 Ma). Transpressive and extensional faulting were observed, in coherence with the main Jura phase, the Messinian crisis and a shift of the regional stress field to N150° E [Van Vliet-Lanoë et al. 2002].

There are some markers of faulting activity over the Plio-Quaternary (compiled in Figure 1A), mostly accommodated along the SASSZ, SANSZ, AUFZ, ESZ and the Yeu-Ré fault zone (YRFZ), but also along KF, and the Somme (SOF) and the Seine (SEF) faults. New relaxation phases during early Pliocene and the Gelasian (∼2.5 Ma) generated an uplift in central Brittany [Van Vliet-Lanoë et al. 2002] and thus a vertical tectonic reactivation of the N130° E–N150° E faulting system of the Armorican Massif, and of the MCFZ in a transtensive manner (Confluent Zone, Figure 1A). Finally, note that volcano-tectonic deformations occurred since the beginning of the Cenozoic in the Massif Central due to successive phases of volcanic activity [Maury and Varet 1980] which continued in the recent times over the quaternary.

Historical (www.sisfrance.net) seismicity between 462 and 1962. Only earthquakes discussed in the text are labeled.

3. Seismicity features and characteristics

The first testimonies of earthquakes in northwestern France date back to the 5th century. Up to the mid-20th century, archives are the only informations that can be used to describe the seismicity in this region since very few surface geological evidences are known. The testimonies are translated into earthquake intensities using a macroseismic intensity scale such as the MSK-64 scale [Medvedev et al. 1964], used in the French historical macroseismic intensity database [www.sisfrance.net, Jomard et al. 2021] managed by the BRGM (Bureau de recherches géologiques et minières), EdF (Électricité de France) and IRSN (Institut de radioprotection et sûreté nucléaire) consortium.

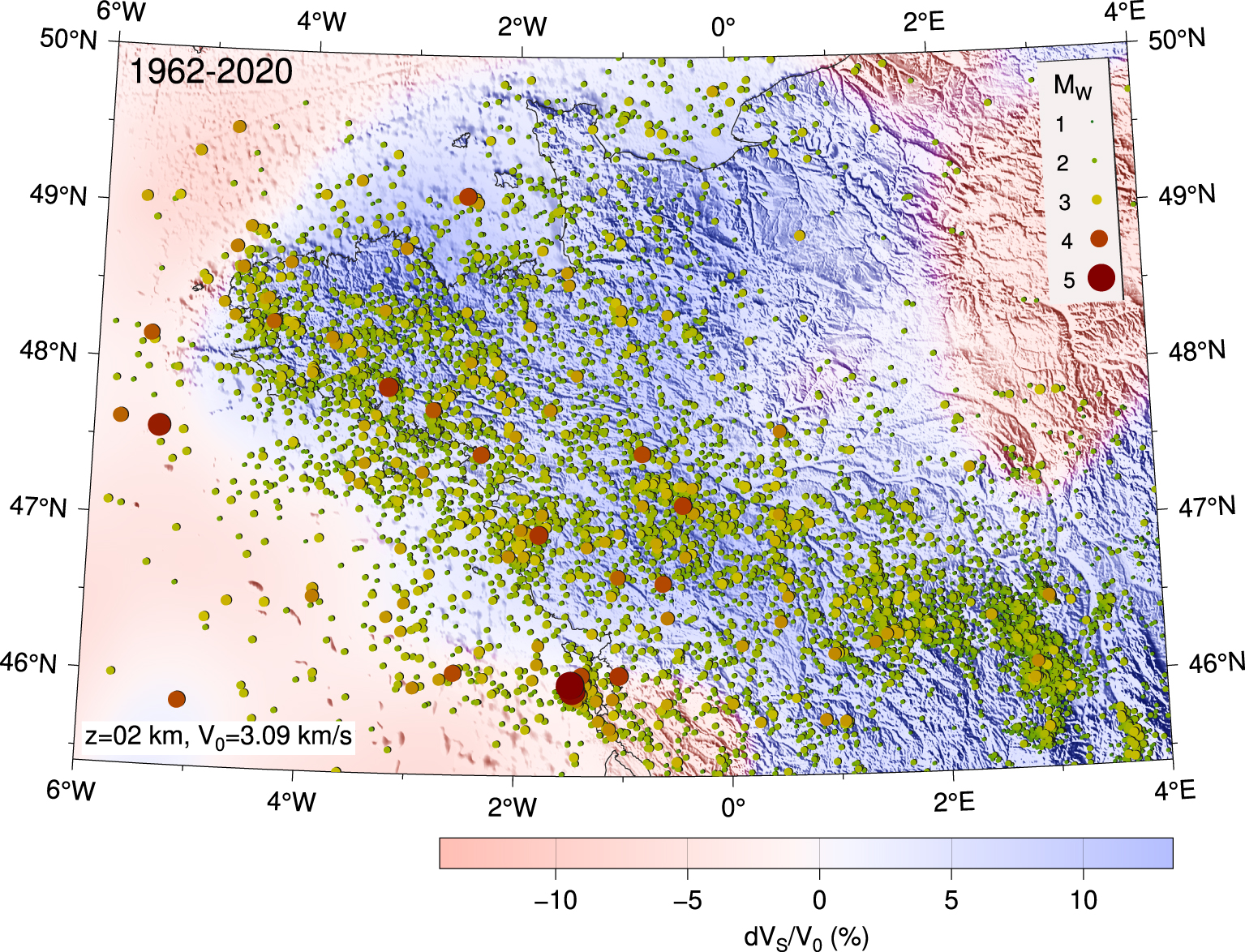

Instrumental seismicity from 1962 to 2020 [Cara et al. 2015 for 1962–2009 and a unified catalog for 2010–2020]. The background color scale represents VS perturbations at 2 km depth [Gaudot et al. 2021].

Reliable instrumental seismicity catalog in the northwestern France started in the 1960s with the deployment of the first seismic network by the CEA. The seismic coverage in the region has changed significantly over time (see Section 3.3.1).

3.1. Historical data (469–1962)

The first record of an earthquake felt in the northwestern part of metropolitan France dates back to November 469, in the Angers area [Alexandre 1990]. The effects of this earthquake on the population and the buildings are, however, poorly documented. The first testimonies with such detailed descriptions are associated to the 18th April 577 earthquake, indicating an intensity of VI MSK-64 near the town of Chinon (Figure 2). The highest epicentral intensity, VIII MSK-64, was reached in the NW part of France for the 1490 Limagne earthquake (Figure 2). Some other notable earthquakes, among the best documented, that experienced an epicentral intensity of VII–VIII, are the 1579 Berry, 1711 Loudun, and the 1799 Bouin events.

Quantity and quality of intensity data available for historic earthquakes can vary significantly: if many intensity data for recent events are available, it is not the case for older ones. The 577 Chinon earthquake, for instance, relies on only one intensity value. On the other hand, the 1579 earthquake is known by 17 intensity data points located up to 100 km away from the estimated epicenter, although the coverage in the epicentral area is relatively low. Indeed 67% of the earthquakes in this region have an estimated epicentral intensity and location that are associated with a very low confidence level, in particular for events such as Jersey 1926, Coutances 1853, or Cherbourg 1889 earthquakes (epicentral intensities of VI–VII for 1926 and 1853, VI for 1889), largely felt in the Normandy area and in the South of the England, and for which locations are most likely at sea. However, the MW magnitude of Jersey 1926 has been recently evaluated to 5.0–5.5 [Amorèse et al. 2020] which means one of the largest in the whole region during the 20th century (Figure 3) although larger events are reported in the historical dataset. It has been followed by a slightly lower magnitude event in the same area eight months after (Jersey 1927). During the major part of the 20th century, before the first deployment of regional seismic networks, it seems that this part of the metropolitan France has only experienced few significant earthquakes such as the 1930 Vannes earthquake (Figure 2) and the 1972 Oléron earthquake (Figures 3 and 4), with epicentral intensities of VII MSK-64.

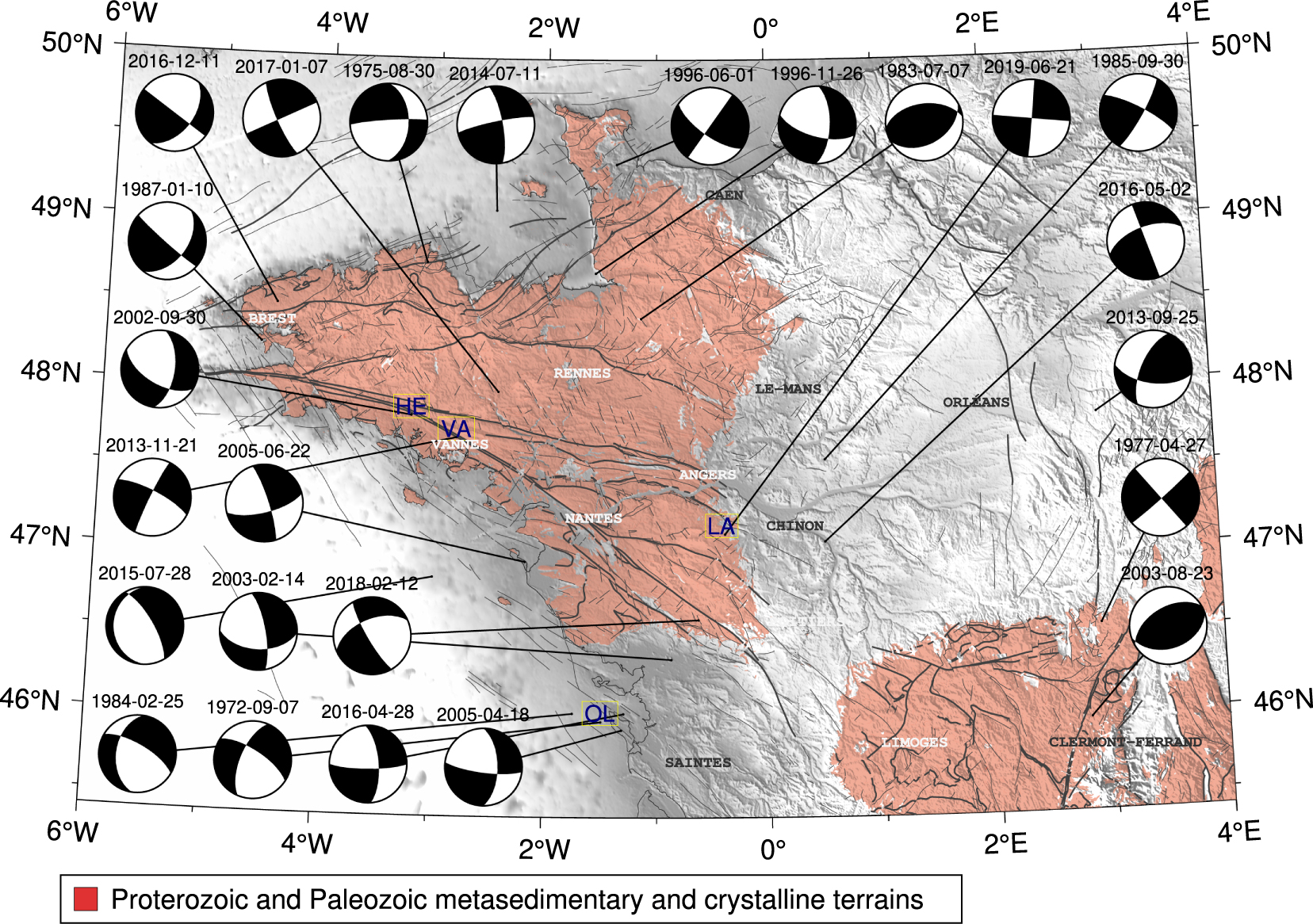

Focal mechanisms of the most important earthquakes during the last 50 years [extracted from Mazzotti et al. 2021]. Major and important faults from the numerical geological map of France [Chantraine et al. 2003] are plotted in thick and thin dark gray solid lines, respectively. The metamorphic and plutonic areas are extracted from the numerical geological map of France (scale 1/1000,000). Letters OL, HE, VA, and LA stand for Oléron, Hennebont, Vannes, and Layon events, respectively.

Within such zones, when the seismogenic potential is estimated based on the analysis of historical seismicity, a proper propagation of the uncertainties should thus be considered [Provost and Scotti 2020]. Reducing such uncertainties requires an important effort in the quest for documents and archives. This is particularly true in Brittany, where unexplored archives are certainly waiting to be discovered, given that the Sisfrance database has not led any specific action in this “nuclear free” zone. A history research program dedicated to this point would be of great interest. Moreover, the current density and geometry of the permanent broadband seismic network in this region should provide a significant reduction in uncertainties. This will lead to better magnitude and depth estimates of the instrumental events used in this region to calibrate empirical intensity–magnitude models. For such a moderate seismicity, the assessment of the seismic potential of a given fault, over several centuries, requires long-term historical testimonies, interpreted in the light of present instrumental data provided by high-quality networks.

3.2. Instrumental data (1962–2020)

At the end of the 2000s, according to the time evolution of the French seismic network, including an increasing number of academic partners, a national effort was required to produce a reference seismicity catalog consistent in terms of both source locations and magnitudes. The SI-Hex project [Cara et al. 2015], led by the BCSF and the CEA, provided a first catalog including improved locations and moment magnitude estimates for the whole metropolitan France, and for the 1962–2009 period. In order to provide a homogeneous catalog, the moment magnitudes are assessed from local magnitudes inferred from various contributors and using different relationships, or directly computed from waveforms for the largest events. In the NW part of metropolitan France (including a part of the Auvergne), 6631 events are located over a total of 38,027. In the absence of a structural model dedicated to this region, the first locations of the hypocenter were carried out using a unique inversion scheme, at the least squares sense, and relying on a three-layer 1D model (upper crust–lower crust–mantle), modified according to Rothé and Peterschmitt [1950]. The preliminary locations were refined by more precise solutions when available [e.g. Nicolas et al. 1990; Arroucau 2006].

For the time period between 2010 and 2020, such a unified catalog does not exist. In the continuity of the SI-Hex project, the RéNaSS provides moment magnitudes which are based on the ML bulletin or waveform inversions. In this study, we present a database derived from both the CEA ML bulletin and this MW BCSF-RéNaSS catalog. When an event is present in both databases the BCSF-RéNaSS solution is retained. The events which are only available in the CEA bulletin are converted to MW magnitudes using the SI-Hex relationships [Cara et al. 2015] and appended. This step ensures that the seismicity database described hereafter between 2010 and 2020 is consistent with the SI-Hex catalog and we detail in this article a homogeneous database for the 1962–2020 period (Figures 3 and S2).

3.2.1. Hypocenter locations

At first glance, the seismicity recorded since the 1960s is characterized by a geographical diffuse distribution, concentrated in the outcrop areas of the basement, with a minority of events scattered on the continental shelf and in the adjacent Paris and Aquitaine basins (Figure 3). The geographical distribution of epicenters remarkably follows the metamorphic and plutonic outcrop areas, which appears to be in good agreement with the positive seismic velocity anomalies (in blue) that are extracted from a tomographic model at 2 km depth [Gaudot et al. 2021]. The largest concentration of events is observed along the direction of the great Variscan structures (N120° E), within a 100 to 150 km wide zone, which extends from the Finistère to the Massif Central.

However, the accuracy of the event location does not allow to precisely associate them with the activity of a particular branch of the former shear zones. Up to 1977, the uncertainty about epicentral locations was actually greater than ten kilometers. The subsequent densification of the network (Figure 5) then made it possible to reduce this uncertainty to values of the order of 5 km [see Figure 2 in Cara et al. 2015]. It is therefore possible that the apparently diffuse nature of the seismicity is partly due to the large uncertainties in the locations, inherent in the small amount of stations available before the deployment of the Résif-Epos project. This uncertainty is particularly important for hypocentral depths, as the small number of available data (onset time phase pickings) often force analysts to test different depth values a priori, or to impose constant value, in the process of inverting arrival times. In the catalog, the fact that about 40% of the hypocentral depth values are of 20 km, i.e., at the base of the first layer of the velocity model, is probably not representative of the true distribution of seismicity at depth.

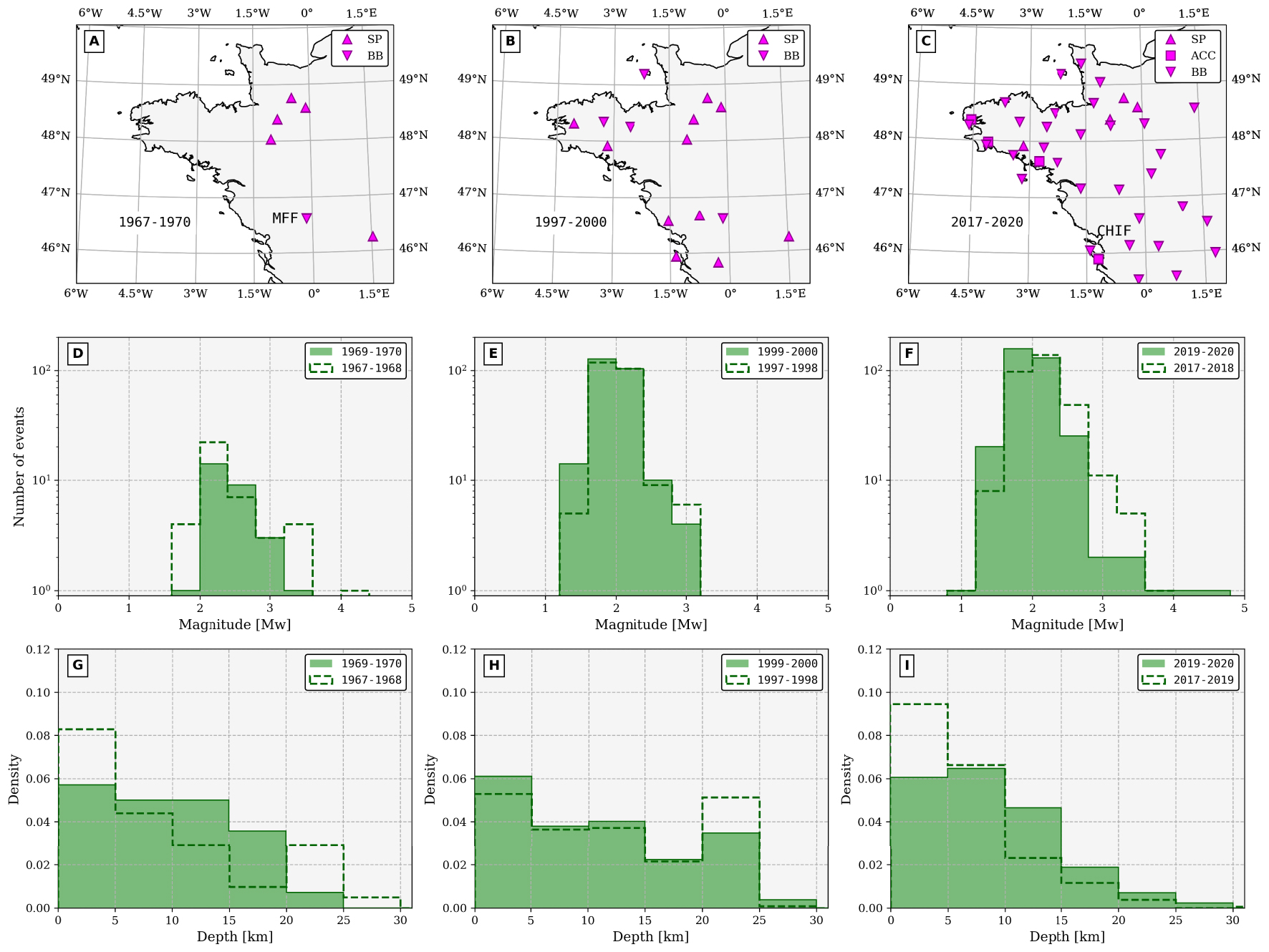

Statistics on moment magnitudes and event depths during three different four-year time windows. The geographical extent of seismic networks is shown in the top row. SP, BB, and ACC stand for short period, broadband, and accelerometer sensors, respectively. The middle and bottom rows show MW and depth histograms. Bins for MW are of 0.4 and those for depths are of 5 km. The dashed line histograms are computed during the two years preceding the thick plain green histograms in order to size a possible evolution with time.

Three remarkable events that have occurred in the last 20 years have been studied in more detail as they benefited from the deployment of temporary post-seismic networks.

3.2.1.1. Hennebont, 2002:

On September 30th, 2002, occurred at 06:44 UTC, an MW = 4.3 (ML = 5.4) earthquake at 12 km depth, close to the city of Hennebont with a mostly normal fault component focal mechanism (Figure 4). Perrot et al. [2005] deployed a seismological array after the mainshock and located accurately 49 aftershocks within 14 days with a magnitude ranging from 0.4 to 1.9 and all located 11.5 to 13.5 km deep. The distribution of the aftershocks defines a rupture plane dipping 60° to the south with a fault length of ≃2 km, at the junction between the northern and southern branches of the South Armorican Shear Zone. Their focal mechanisms (pure right-lateral strike-slip and dominant normal faulting) are consistent with the main shock. The stress tensor obtained from these focal solutions by Perrot et al. [2005] displays a strike-slip regime with a NE–SW extensional direction and the authors proposed that this earthquake reactivated Late Variscan structures.

3.2.1.2. Vannes, 2013:

On November 21st, 2013, at 09:53 UTC, an MW = 3.8 (ML = 4.6) earthquake occurred near the city of Vannes located in the Southwest Armorican Massif (Figure 4). It has been felt more than 100 km around the epicenter, with intensities up to IV (EMS98) at distances less than 25 km. Three aftershocks with ML between 1.8 and 2.2 were detected by the RéNaSS in the 12 hours following the main shock. The day after LPG/OSUNA deployed a temporary array of six short-period sensors around the epicenter with an aperture distance of 50 km. Using this temporary network, which operated for 30 days, 58 local events (not present in the national database) were detected. After a careful study, 12 quarry blast signatures were identified and it turns out that 24 events are located less than 5 km away from the main shock zone and then can be considered as aftershocks [Haugmard 2016]. All depths are ranging between 2 and 12 km. Waveform inversion using FMNEAR [Delouis 2014] led to an almost pure strike-slip fault mechanism. The obvious link with the SASZ tend to conclude to a dextral displacement with two almost vertical nodal planes of azimuths of about 205° and 280° (Figure 4). In the 1962–2020 BCSF + CEA unified catalog, 69 events are located within 25 km of this 2013–11 event location (including those detected using a template-matching detection criterion, Figure 8).

3.2.1.3. Layon 2019:

On June 21st, 2019, occurred at 06:50 UTC, an MW = 4.0 (ML = 4.8) earthquake near the village named Tancoigné (city of Lys-Haut-Layon) in the Maine-et-Loire (Figure 4). The event was felt at more than 100 km around the epicenter, with intensities up to V (EMS98) at distances less than 10 km. 3 aftershocks with ML between 2.3 and 3.0 were detected by the RéNaSS in the 12 hours following the main shock. In the afternoon of June 21st 2019, LPG/OSUNA deployed a temporary network of 8 short-period stations at less than 20 km from the epicenter. This array allowed to detect 156 aftershocks between 13:00:00 UTC on June 21st and 07:00:00 UTC on June 25th. Waveform inversion using FMNEAR [Delouis 2014] led to an almost pure strike-slip fault mechanism with one of the nodal plane oriented close to E/W (Figure 4). The preferred solution from this inversion indicates a superficial focal depth (approximately 6 km) which is in good agreement with the solutions proposed by the BCSF-RéNaSS (10 km), the CEA [5 km, Duverger et al. 2021], and the analysis of the 156 aftershocks [6 km, Bonnin et al. 2019]. The epicenter is located at approximately 10 km to the southeast of the Layon fault. The N–S/E–W nodal planes obtained from FMNEAR is not, however, in agreement with the N120° E trending major fault traces in this zone. This would suggest the rupture of an unknown secondary fault, possibly associated with the main Layon fault.

Since 1962, the recording of seismic signals in Auvergne is continuous which provide a good knowledge of instrumental seismicity. We present in Figure S2 the location of all the earthquakes that could be located during the period 1962–2020. In an area delimited by longitudes 1.1° E and 4° E and latitudes 44.7° N and 47.4° N, 4858 epicenters are reported [see Sylvander et al. 2021, for a complementary analysis]. Over the last 40 years, around 100 earthquakes per year are located in this region. Since 1962, 19 earthquakes have an MW between 3 and 3.4 and 1276 a magnitude between 2 and 3. All earthquakes with magnitude greater than 1.8 are currently located. The depth of seismicity in Auvergne is non-uniform and mainly superficial (depths ⩽11 km) [Dorel et al. 1995; Mazabraud et al. 2005; Battaglia and Douchain 2016]. There are four main areas:

A diffuse and relatively significant seismicity northwest of Clermont-Ferrand, in a quadrilateral formed by the cities of Clermont-Ferrand, Limoges, Châteauroux and Moulins. It groups more than 50% of the seismicity observed in the Massif Central. Northwest of Clermont-Ferrand, on either side of the Sillon Houiller (SH in Figure S2), the Combrailles area is the most active, both in terms of the number and magnitude of earthquakes. Most earthquakes seems to be located on secondary faults and their occurrence is fairly regular with relatively few earthquake swarms. To the north, the region of Cosne d’Allier, west of Moulins, has been affected by a significant seismic crisis (of about 100 earthquakes) between June, 1984 and January, 1985. Although not located near known faults, this swarm may be related to the Sillon Houillier. Finally, further west, near Guéret, a persistent and fairly diffuse seismicity is observed. Part of this seismicity could be associated with the various segments of the La Marche fault present in the region (LMFZ in Figure S2). This seismicity then extends toward the west of France, making the link with the Armorican seismicity.

The Monts Dore region is characterized by a seismicity in the form of swarms lasting from several days to several weeks with nearly 300 earthquakes located since 1962. The two main swarms occurred in 1980 and 1984 including 79 and 37 events distributed, respectively, over 1 month and 4 days. The temporal and magnitude distribution of these seismic swarms often does not present the usual sequence of a mainshock followed by its aftershocks.

In the Ambert graben, seismicity is concentrated on the western edge of the basin. Several earthquake swarms are observed. A large part of this seismicity is probably to be related to the old Oligocene faults of the Ambert basin.

The Saint-Flour region is the site of both clustered and diffuse seismic activity whose part of it could be interpreted as a reactivation of the fault system bordering the Saint-Flour graben. This area is described with more details in Sylvander et al. [2021].

Overall, there is low seismicity under much of the Chaîne des Puys, a Quaternary volcanic chain, and no earthquakes could be clearly identified in the region as having a volcanic origin.

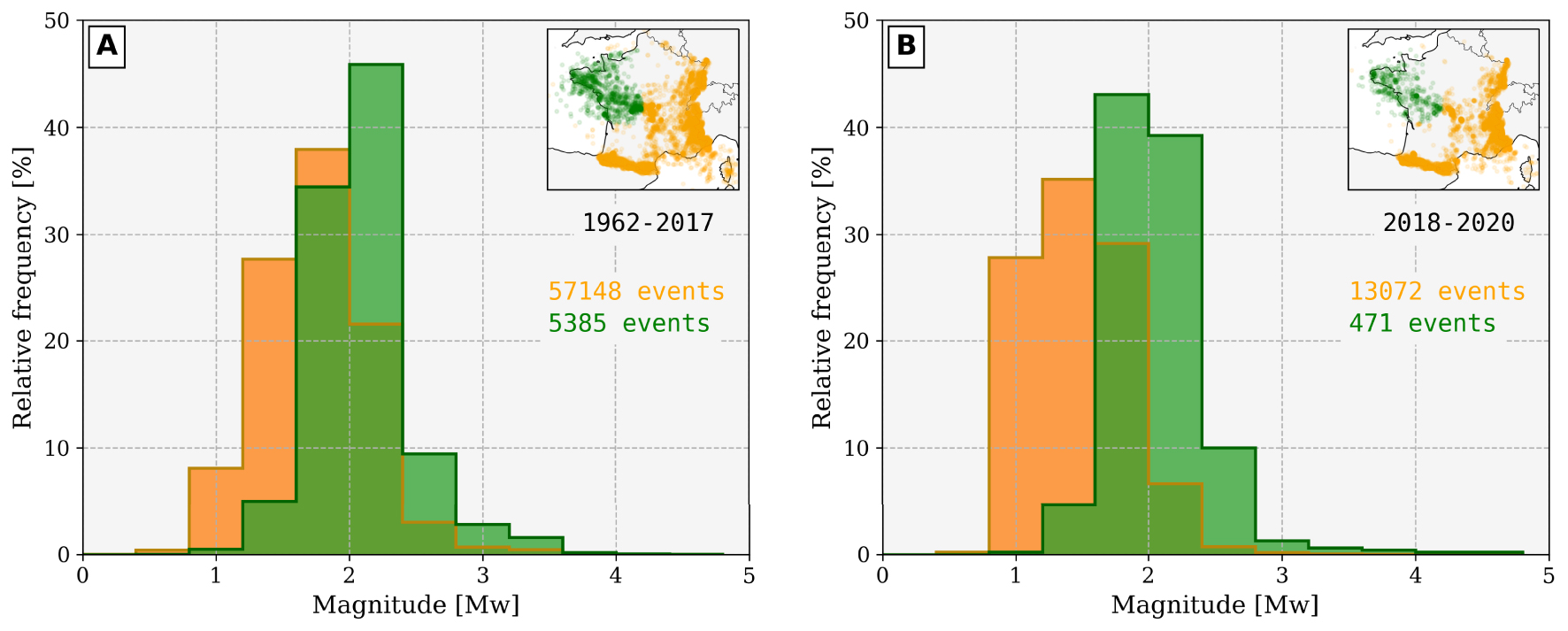

Respective distributions of moment magnitudes for the western part (green) and for the rest of metropolitan France (orange) during two different time ranges. The green histograms are computed for a region comprised between 2° E and 6° W and 45.4° N and 50° N, using bins of 0.4.

3.2.2. Magnitudes

As explained above, figures and statistics presented in this article rely on the unified database composed by SI-Hex catalog for events before 2010 and a merging of the BCSF-RéNaSS catalog with the CEA bulletin (see Section 3.2). It is of first importance, when comparing the MW values in the NW France with the rest of the country, to keep in mind that this region is characterized by significant lower attenuation. This can be observed from both a macroseismic [Arroucau et al. 2006; Bakun and Scotti 2006] and an instrumental point of view [Mazabraud et al. 2013]. The quality factor measured on coda waves is 30% to 50% higher than the metropolitan average at frequencies larger than 1 Hz [Mayor et al. 2018]. This can lead to a significant overestimation of magnitudes, as observed for instance for the Hennebont earthquake (Figure 4), with magnitudes ML = 5.7 and MW = 4.3 [Perrot et al. 2005]. The large ML value, calculated from the amplitude of the Lg waves, contrasts with the study of Cara et al. [2017] for 59 earthquakes of magnitude ML–CEA > 4 during the period 1997–2013, which results in a difference of 0.6 between local and moment magnitudes at a metropolitan scale in agreement with the conversion laws proposed by Braunmiller et al. [2005]. The low attenuation properties of the basement zones, combined with the low spatial density of the pre-Résif-Epos seismological network, also result in a bias in the statistical distribution of magnitudes, with a magnitude of completeness of ≃2 in the West, whereas it is about 1.5 elsewhere in France.

Figure 6 presents the relative distributions of MW in the NW part of France (green) and the rest of the country (orange). The green region does not include Auvergne since this area is instrumented for a longer time than the rest of the NW France (see Section 3.3.1). The catalog analysis is made for two distinct time ranges (before and after 2018), in order to size the major change in the seismic coverage which started in 2018 (Figure 5).

For time period 1962–2017 (Figure 6A), the seismicity of the metropolitan France is approximately composed of 10% of events located in the NW (all magnitudes included). This ratio can vary from ∼20% for magnitudes in the range 2.8–3 to 5% or less for magnitudes lower than 1.5. The magnitude distribution in NW France presents the following characteristics: 80% of the magnitudes are between MW = 1.6 and MW = 2.4 (60% for the other regions), 15% are above MW = 2.4 (5%), and only 5% are less than MW = 1.6 (35%). The dramatic lack of events MW < 2 in the NW is mainly caused by the sparsity of the seismic network in this region before the 1990s (Figure 5). The relative abundance of MW > 2.2 with respect to the orange zone is likely due to an overestimation related to the low attenuation of the Armorican Massif crust.

The most recent time period (2018–2020), that sees an historic increase of seismic stations, is interestingly not (yet) associated with a significant change in the MW distribution pattern in NW France. Although about 80% of the MW are still between 1.6 and 2.4, the mode of histogram decreases down to MW = 2.0, indicating that smaller events are better detected than before. One can however notice that the detection of smaller events (MW ∼ 1 in Figure 6) is much more improved in the rest of the France (from 8% before 2017 to 28% after 2017), thanks to the rising of Résif-Epos. In this time range only 3.5% of the overall seismicity in the database is located in the NW. As discussed in Section 3.3.2, this understanding of the small magnitude seismicity can be, however, largely influenced by the method used to detect natural events.

3.2.3. Focal mechanisms

180 focal mechanisms have been determined in the west of metropolitan France for more than thirty years [Nicolas et al. 1990; Amorèse et al. 2000; Mazabraud et al. 2013; Delouis 2014]. They are available in the unified database fmhex [Mazzotti et al. 2021] and a selection of them is represented in Figure 4. This subset is based on (i) magnitudes, in order to present the most significant events of the studied region, (ii) locations, in order to show the geographical variety of the solutions, and (iii) the most consensual data because some earthquakes have very different focal mechanisms. The majority of old focal mechanisms are obtained from first motion polarities using sparse permanent short-period networks while the most recent are determined from waveform inversion of the closest unsaturated broadband and strong ground motion records provided by denser regional networks [method FMNEAR, Delouis 2014]. Some of them (Hennebont, 2002; Vannes, 2013 and Layon, 2019) are further assessed by postseimic campaigns in the epicentral area (see Section 3.2.1).

As the broadband network in the NW France has been progressively developed over the last years, some of the FMNEAR solutions (e.g. 2013-11-21 or 2016-04-28, Figure 4) are obtained with as few as three stations. Although we systematically verified that the solutions displayed here were well constrained, which means that no significantly different focal mechanisms could be found to explain the waveforms data, the uncertainties may vary from one mechanism to another. Detail on the solutions is available at http://sismoazur.oca.eu/focal_mechanism. A critical and comprehensive study of the database is beyond the scope of this paper, but a representative set of mechanisms displayed in Figure 4 allows to outline the general patterns of the deformation. With a few exceptions (e.g. the pure inverse 1983 and 2003 mechanisms in the South of Normandy and close to Clermont-Ferrand, respectively), all major events in the region of interest display significant strike-slip motions associated with normal components, with P and T axis orientations grossly varying around NW–SE, and NE–SW directions, respectively. The associated nodal planes are coherent, on a regional scale, with the orientations of the previously described faults and shear zones. Finally, most of these mechanisms are consistent with a uniform NW–SE to NNW–SSE compressional stress field.

3.3. Influence of the seismic network

3.3.1. A long history of sparse seismic coverage

In Auvergne, the OPGC installed its first seismological station at the top of the Puy de Dôme in 1906. This station was moved to the Observatory in 1913. Since that date, recording is continuous at OPGC, but with low amplification equipment until 1980. The original station was renovated in 1980, then supplemented by a true network covering the region and including telemetry. As of 1986, the Auvergne Seismic Network (ASN) included a minimum of seven permanent stations integrated in the RéNaSS. In the early 2000s, the development of the French accelerometric network allowed the installation of eight accelerometric stations in Auvergne. Since 2010 and the development of the national Résif-Epos network, the RéNaSS short-period sensors are replaced by broadband stations, meeting international standards. The ASN is now increased by seven stations. It currently runs 22 stations (Figure S2) belonging to the national monitoring networks as well as three stations of the “Sismos à l’école” educational network [Courboulex et al. 2012].

As in many other regions, the CEA deployed permanent low-noise stations in the West of France since the 1960s. The main objective was to detect nuclear explosions around the world. This network includes short-period and few broadband sensors and evolved during the last 60 years. In the NW part of France, it contributes a lot to the knowledge of seismicity.

In Brittany and along the Atlantic coast, although a few notable events occurred during the first half of the 20th century (Figure 2), the first academic effort to instrument this region dates back to the 1972 Oléron earthquake (OL in Figure 4). The RéNaSS, which was created in the early 1980s, deployed permanent stations in the city of Rennes (STS-2 broadband sensor) and near Brest. Some on these so-called isolated stations were operating up to the 2010s. Between 1995 and 2008, an additional network supervised by the RéNaSS and maintained by the OPGC and La Rochelle University has been deployed around the Isle of Oléron (Charente network). It was mostly composed of short-period sensors except MFF and CHIF station, the second broadband station of the NW part of France. The latter is still in operation today with some recent important quality improvements (borehole installation).

Cumulative plot of both natural and anthropogenic events of ML⩽1.75 as a function of time. The amount of permanent French operating stations is plotted in red (labels on the right, including network codes RD, RA, FR). From mid-2018, thanks to the permanent deployment of Résif-Epos broadband stations in the West, the amount of natural events increased significantly but less than the quarry blast detections and military explosions (gray). Event acronyms: VA (Vannes), SH (Saint-Hélier), LR (La Rochelle), FC (Fontenay-le-Comte), LA (Layon), and BR (Brest).

The most important change in the seismological observation of this region has been brought by the broadband component (RLBP) of national project Résif-Epos that started in 2010 and ended in 2021 (Figure 5C). Among the 28 new broadband stations that were planned to be deployed in the whole NW quarter of France, 24 were already operating at the end of 2021. Due to the difficulty of finding sites in natural cavities or caves, most of the stations are installed in boreholes at depth comprised between 6 and 25 m. The stations are maintained by the OSUNA within the Résif-Epos consortium. Few accelerometric sensors are installed along the SASSZ and near Isle of Oléron. Given the current seismic coverage, the coming decades will see an unprecedented amount and quality of data in the northwestern part of France.

3.3.2. Toward a comprehensive catalog?

With the densification of a seismic network comes the question of the event detection which rapidly turns into the discrimination between natural quakes and anthropic signals. The CEA routinely discriminates between natural and anthropogenic events and, since 2013, the RéNaSS does as well. The high-frequency (>10 Hz) non-natural signals are mostly related to quarry blasts, military training operations, and explosions of underwater mines along the French coast, long-term consequence of World War II. As an example, cumulative plots for both natural events and human activities of local magnitude (ML) lower than 1.75 are displayed in Figure 7. The dataset comes from a unified ML BCSF + CEA bulletin between June 1st, 2013 and December 31st, 2020 for the region between 6° W and 2° E (same strategy as for MW, as described in Section 3.2 but without the ML-to-MW conversion). Since the objective here is to highlight the consequences of the transition from very sparse to dense coverage, the Auvergne region is not taken into account.

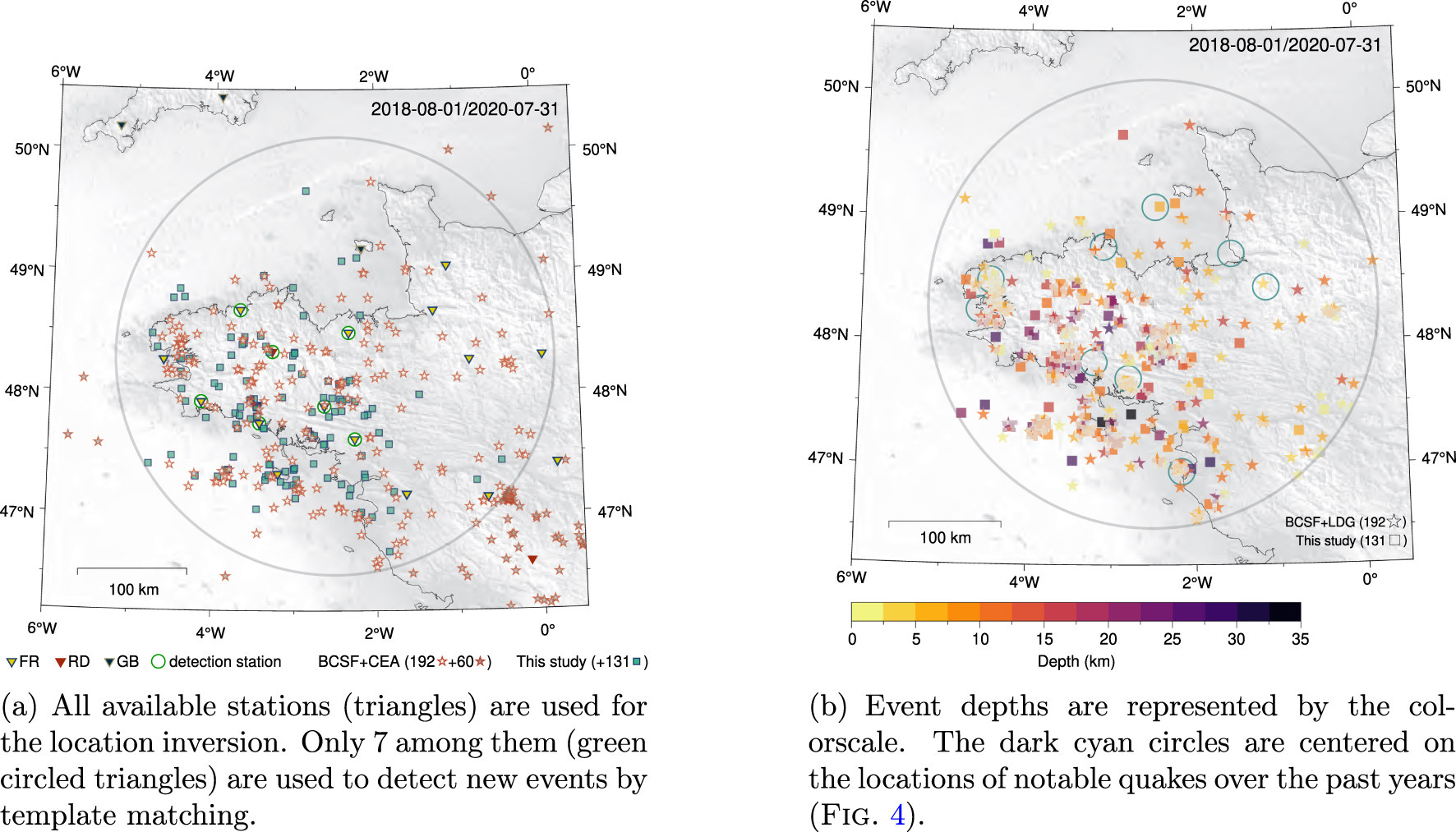

Locations and depths of all events detected during a two-year period. The region of interest is defined by the gray circle (200 km radius, centered at 48.3° N, 2.5° W). 192 events (stars) are reported in the unified BCSF + CEA catalog and 131 new events (squares) are detected and localized in this study.

Although the first deployment of new permanent Résif-Epos stations, installed in the West in mid-2018, slightly increased the amount of natural event detection, the most significant change took place in 2019. It coincided with the finalization of the deployment of the stations in Brittany (Figure 8). Exactly the same features are observed for anthropogenic events but with a slope about four times steeper (gray area in Figure 7). It was expected that more anthropogenic events would be detected in this area thanks to the new network but not to this extent. As a result, the efficiency of a dense, high-quality seismic network can be degraded (see Figure 6) due to the detection/location methods that involve both automatic procedures (implying unavoidable threshold values) and human work. One of the challenge in the near future is to determine some reliable proxies for automatic discrimination of such impulsive waveforms while ensuring the possibility of detecting unexpected weak natural signals.

The detection and the location of all possible low-magnitude earthquakes are key points to further discuss the possible sources and triggering scenario for intraplate seismicity. In order to progress toward a reliable estimation of the magnitude of completeness, we investigate a different scheme for event detection based on template matching [e.g. Gibbons and Ringdal 2006; Peng and Zhao 2009]. Using the best configuration of broadband seismic coverage as ever reached in Brittany, the period of interest starts with the installation of three permanent stations in July 2018. Two years of continuous data, between August 1st, 2018, and July 31st, 2020, are used in this study. The region of interest is defined by the gray circle (Figure 8).

252 natural earthquakes are reported in the unified BCSF + CEA MW catalog within the whole area and 192 are located in the gray circle (red stars with white centers in Figure 8). The moment magnitudes are ranging between 1.2 and 3.3. From this database a subset of template signals (e.g. Figure S3) is created using the waveforms of 40 master events. They are recorded at seven stations represented by green circled triangles. The other triangles symbolize stations used for location only. For each component of each station, all templates are normalized cross-correlated with the two-year continuous seismic signal (using a high-pass filter at 2 Hz). A cross-correlation value greater than 0.2 at three stations or more, is used to pre-select the time windows (with a time tolerance of 60 s) that potentially contain a seismic event. For this study, the 0.2 threshold value is set empirically in order to detect as many events as possible without being overwhelmed by false detections.

1571 selected time windows are extracted from the raw data and after a visual inspection and hand-made picking step it turns out that 318 come from natural earthquakes with clear crustal P and S wave phases. Almost all quakes reported in the catalog are also detected using this template-matching approach. Five events are however not recovered because they meet the detection criterion at only two stations, and not three. These five quakes occurred all in the eastern part of the study area, which is somewhat logical when considering (1) the distance to the detection stations, (2) the fact that all master events are located west of 1.5° W, and (3) their magnitudes that are likely to be lower than 1.2.

Nevertheless, 131 events (blue squares in Figure 8a) are clearly associated to natural quakes and do not belong to any catalog. These unpublished events are consistent with the quakes that are reported in the catalog, both in terms of location and depth (Figure 8b). At first glance they do not necessarily match areas surrounding previous notable quakes recorded in the past (the dark cyan circles correspond to the location of events shown in Figure 4), except for Vannes, 2013 and Brest, 2016 events.

4. Possible geodynamic factors controlling the seismicity

As shown in the previous sections, the northwest part of France is characterized by a seismicity that is both frequent (∼0.4 event/day) and weak to moderate in terms of magnitude. It is often described as diffuse, although this later characteristic may reflect, in part, the seismic network geometry. Northwestern France has undergone several major tectonic events since the Paleozoic (cf. Section 2), however it is now considered as a stable continental region [SCR; Johnston 1989] located far from plate boundaries and, consequently, subject to extremely low strain rates [Masson et al. 2019]. Such persistent seismicity in SCRs where current strain rates are indistinguishable from zero is well documented, with examples all over the globe such as in the New Madrid area [Central USA, e.g. Craig and Calais 2014], in Australia [e.g. Clark et al. 2012], as well as in South Africa [e.g. Saria et al. 2013]. As in these SCRs, analysis of the potential geodynamic factors controlling the seismicity in northwestern France is particularly complex due to the limitations and inhomogeneity of historical and instrumental earthquake catalogs, which strongly limits the association with specific faults and tectonic structures. The following discussion on geodynamic controls on the seismicity is divided into three main components: (1) plate-scale steady-state background stress, (2) regional and local modulations of the background stress field, and (3) effect of structural inheritance on the mechanical behavior of faults subjected to these stresses [see Mazzotti et al. 2020, for a recent review for the metropolitan France].

4.1. Plate-scale stress field

In northwestern France, the present-day stress field derived from earthquake focal mechanism inversions and few in situ stress measurements is characterized by an overall NW–SE orientation of the maximum horizontal stress and a general extensive to transtensive tectonic style with a NE–SW deviatoric tension [e.g. Paquin et al. 1978; Mazabraud et al. 2005, see also Figure 4]. This pattern is consistent with the large-scale stress field observed over most of France and Western Europe away from the Mediterranean area. Plate-scale mechanical models show that this background stress field can be attributed to a combination of tectonic forces acting along the boundaries of the Eurasia plate, mainly the North Atlantic Ridge push and the Eurasia–Nubia convergence [Gölke and Coblentz 1996; Cloetingh et al. 2005].

In the current geographic reference frame, the regional NW–SE compressive stress is compatible with the paleostress from past major tectonic events, namely NNW–SSE compressive and transpressive stresses during Paleozoic orogens, and NE–SW extensional stresses during the Mesozoic Atlantic and Bay of Biscay opening (cf. Section 2). Therefore, the faults and shear zones formed during these tectonic events are favorably oriented for failure in the current NW–SE to NNW–SSE compression stress field. Even without significant tectonic loading rates, they can thus be activated in strike-slip and extensional motions as shown by regional focal mechanisms (Figure 4).

4.2. Local and temporal stress modulations

As in other SCRs, seismicity in northwestern France may be sensitive to local stress perturbations that can be associated with numerous factors acting at different time scales [Levandowski et al. 2018], e.g. Spatial variations of gravitational potential energy on Myr periods [Camelbeeck et al. 2013]; Flexural and isostatic adjustment to erosion and sedimentation on periods ranging from Myr [Champagnac et al. 2007; Vernant et al. 2013] to kyr [Calais et al. 2010]; Flexural and isostatic adjustment to 10–100 kyr glacial cycles [Luttrell and Sandwell 2010; Steffen et al. 2014]; Mechanical response to very short (days to months) hydrological or meteorological transients [e.g. Bollinger et al. 2007; Steer et al. 2014; Leclère and Calais 2019]. Such interactions between tectonics, mass redistributions, and structural inheritance, have been documented in other contexts [e.g. Sue et al. 2002; Sternai et al. 2019].

The Armorican Massif is located in a context of passive margin formerly in a periglacial domain. In similar contexts closer to the large Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) icecaps (e.g. northeastern Canada, Fennoscandia), the interactions between far-field tectonics, structural contrasts at the continent–ocean transition, and LGM glacial isostatic adjustment can result in significant stress perturbations, up to a few tens of MPa that have been associated with seismicity crisis [Stein et al. 1989; Steffen et al. 2014].

Northwestern France is located between 500 and 1500 km far from the Fennoscandian and Celtic icecaps, roughly 500 km from the Alpine ice fields, and in a range of 10–100 km from the minor Massif Central glaciers. The potential effect of these different sources remains to be studied, but it is likely much smaller than that observed below and very close to the large icecaps. Evidence of post LGM seismic and aseismic deformation in the periglacial context of northwestern France remains controversial [Van Vliet-Lanoë et al. 2017].

Similarly, erosion/sedimentation and hydrological or glacio-eustatic forcing may influence by isostatic compensation the seismicity in northwestern France, but their actual impact in the local context remains to be studied in details. In particular, on-land erosion coupled with sedimentation on the Atlantic and Channel margins may result in an overall isostatic/flexural/elastic response that would favor surface extension on land, thus promoting regional transtensional deformation and local permutations of the vertical and maximum horizontal stress as observed in the earthquake focal mechanisms [Mazzotti et al. 2020]. On a shorter time scale, large erosional/mass wasting events may impact stress loading in the shallow part of the crust and transiently increase the frequency and the b-value of earthquakes [Steer et al. 2020; Jeandet Ribes et al. 2020].

4.3. Tectonic and fault inheritance

Due to the limitations on instrumental and historical earthquake catalogs, on potential active fault data, and on neotectonic evidence, it is challenging to associate a given earthquake to a fault in northwestern France (as in most SCRs). Thus, the links between significant earthquakes and fault evidence at the surface vary significantly. The South Armorican Massif is well documented in terms of fault geometry (Figure 1A), allowing tentative associations of the inherited tectonic structures with the seismicity (e.g. 2002 Hennebont earthquake, Section 3.2.1). Similar associations are much more difficult to draw in the Chinon region (SE extension of the South Armorican Shear Zone), the Cotentin area (1853, 1889, and 1926 earthquakes), the Vendée (1799 earthquake), and the Limagne area (1490 earthquake). The latter highlights the difficulty in associating seismicity with tectonic features: although the seismic activity is organized along a NW–SE axis, which corresponds to local known tectonic structures, very few studies on fault activities are available in this region.

Although there is no clear evidence of surface rupture of major faults, the potential control of the current seismicity by inherited structures is suggested by a few specific studies. Kaub et al. [2021] suggest that the Machecoul fault (similar to the Seudre/Oléron, Yeu-Ré, Noirmoutier Faults, Figure 1A) was active from the Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous to the present time and may be responsible for significant events such as an M = 6 Bouin 1799 earthquake (Figure 2). Since the known Variscan structures extend Eastwards without noticeable historic nor instrumental earthquakes (Figures 2 and 3), the impact of the tectonic inheritance may be annihilated by the effect of sedimentary pile thickness. This effect of mechanical variations in regional models is quantitatively addressed by recent numerical modeling studies [Paris basin; Petit et al. 2019] and by more generic integration of inherited mechanical weakening in SCR conditions [Mazzotti and Gueydan 2018; Tarayoun et al. 2019].

These various points show that the regional seismicity likely involves complex interactions between very slow tectonic loading and remnant stress, fault reactivations with long recurrence times, isolated events controlled by weak fault strength, and potential transient stress perturbations. In relation with this complexity, Calais et al. [2016] proposed that the dynamics of earthquakes differ in plate boundary and SCR contexts. Classically, in the former, major earthquakes are expected when accumulated stress reaches the strength of the fault after a short loading period (10s–100s yr). In contrast, earthquakes in SCRs may be triggered by perturbations of the local stress or fault mechanical properties in a pre-stressed lithosphere without stress accumulation prior to the earthquake, rendering the concepts of recurrence time and slip rate inapplicable. Whether this difference in deformation and earthquake dynamics is actual, whether it is limited to large earthquake, or whether it applies to seismicity in general, those questions are central to better understand seismicity in northwestern France.

5. Conclusion

The seismological data provided by the BCSF-RéNaSS and the CEA to the community over the past century, combined with the densification of the new Résif-Epos observation networks, will be the basis for a better understanding of low-to-moderate magnitudes events in the northwestern part of France. Several possible origins of intraplate seismicity may co-exist and reliable discrimination between them can only be achieved by a careful and detailed long-term study of the seismicity. When looking for low-magnitude events in such a stable continental region, the geometry, the longevity, and the quality of the seismic network acts as a filter that blurs real differences in behavior, if they exist.

In the quest for determining the magnitude of completeness in a given region, at least four points are crucials: (1) the seismic network efficiency (signal quality, station density, data availability), (2) the detection method, (3) the event location accuracy (especially source depth), and (4) the structure model (velocity, anisotropy, and attenuation). We show in this article that, when using new detection methods, the national broadband seismic network in this current configuration in the NW France is able of lowering the magnitude detection threshold below 1. However, in the future, a dense network raises the difficult task of using efficient detection/discrimination algorithms [e.g. Allmann et al. 2008; Meier et al. 2019] in order to lower the magnitude threshold as much as possible while avoiding being overwhelmed by human activity signals (e.g. quarry blasts, military explosions). Automatic phase picking methods [e.g. Zhu and Beroza 2018; Woollam et al. 2019], combined with sophisticated and reliable inverse algorithms for depth determination, can be a powerful workflow to make the most of the network’s quality. To better understand the factors that control the SCR’s seismicity, such as in the northwest of France, one of the keys is to assess its diffuse behavior. Given the sparsity of the seismic networks over the last 50 years, this might be an artifact and the coming decades will be a turning point in the quantification of this low-to-moderate intraplate seismicity. Different local and temporal stress modulations, that can be considered as negligible (or hidden) in the plate boundary regions where the tectonic drives the seismicity, can become more important when this latter decreases in strength (e.g. in SCRs). They can all co-exist with an importance that can vary with space and time. In the coming decades, the observations provided by the new seismological network, now in place, will be the essential basis for understanding the different processes that control seismicity, thus allowing for a better assessment of the seismic hazard in northwest France.

Acknowledgments

Résif-Epos is a Research Infrastructure (RI) managed by the CNRS-Insu. It is a consortium of eighteen French research organisations and institutions, included in the roadmap of the Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation. Résif-Epos RI is also supported by the Ministry of Ecological Transition. RESIF; (1995): RESIF-RLBP French Broad-band network, RESIF-RAP strong motion network and other seismic stations in metropolitan France. RESIF—Réseau Sismologique et géodésique Français. doi:10.15778/resif.fr. The construction of the new permanent French broadband seismic network is funded by the ANR (11-EQPX-0040). All maps except Figure 1 are made using GMT 6 [Wessel et al. 2019]. Authors warmly thank an anonymous reviewer, C. Larroque and M. Godano for their constructive reviews and C. Petit for her work as editor. We share the pain of having lost our colleague and friend Christophe Clément, who deceased four days after this article was accepted for publication.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0