Version française abrégée

1 Introduction

Le long des marges actives, la convergence est le plus souvent oblique : lorsque l'obliquité de la convergence est suffisante, le mouvement relatif des plaques est partitionné à la frange de la plaque supérieure et un système de décrochements, accommodant tout ou partie de la composante de déplacement parallèle à la marge, se développe. La localisation de ces zones décrochantes diffère en fonction de la nature et de la géométrie, essentiellement l'angle de plongement, de la plaque subductée. Ainsi, une plaque subductée épaisse et/ou légère plonge faiblement et accentue le couplage inter-plaque, créant des conditions favorables à l'apparition d'une tectonique décrochante. Celle-ci se situe, soit immédiatement à l'arrière du prisme d'accrétion, comme dans l'archipel des Ryukyu [15], soit à l'arrière du prisme jusque dans l'arc volcanique, comme en Indonésie occidentale [2,12,19,20], soit au sein même de l'arc, comme dans l'archipel philippin [24,25], soit encore plus loin à l'arrière du domaine d'arc, comme dans les Andes septentrionales, où les décrochements recoupent l'extrémité distale de la lithosphère continentale [13], voire à la limite du bassin arrière-arc, comme au Japon méridional [14]. Lorsque, à l'inverse, le fort plongement d'une plaque dense conduit au retrait de la fosse de subduction et à l'ouverture d'un bassin arrière-arc, ce dernier domaine constitue, dès son apparition, une zone de faiblesse particulièrement apte à accommoder le déplacement longitudinal [6]. Des levers bathymétriques et géophysiques récents [5,10] ont montré que tel est le cas du bassin arrière-arc du Havre, au nord de la Nouvelle-Zélande.

Longitudinalement, le dispositif varie [18] à la suite d'une inflexion dans l'orientation de la zone de subduction par rapport au vecteur de convergence. Soit l'orientation de la frontière de plaques, en s'infléchissant, se rapproche de celle du vecteur de convergence et la subduction oblique cède progressivement la place à une frontière en coulissement (Nord de Sumatra) ; soit, à l'inverse, la subduction s'effectue sur une frontière rectiligne, mais située à proximité du pôle relatif de rotation. Dans ce dernier cas, en s'éloignant du pôle, la convergence devient de plus en plus frontale et la part de tectonique décrochante diminue. Ceci se produit, en Nouvelle-Zélande, aux deux extrémités de la faille Alpine au sud [4,9,16], comme au nord [1,3,7,11].

2 Quel prolongement vers le nord-est du mouvement décrochant dans l'ı̂le nord ?

Le cas de la subduction oblique qui se manifeste le long du fossé de Hikurangi, au large de la côte est de l'ı̂le nord de Nouvelle-Zélande, pose de ce point de vue un problème. En effet, 500 km de déplacement minimum sont reconnus, plus au sud, sur la faille Alpine. Cette valeur, déduite du décalage entre les affleurements de la suture péridotitique de la Dun Mountain, de part et d'autre de la faille Alpine, atteindrait même 800 km, si la courbure de ce marqueur et des structures associées de l'orogenèse Rangitata (Trias–Crétacé inférieur) devait être prise en compte. Cependant, un coulissement d'une telle ampleur n'est pas identifié au nord, à l'arrière du prisme d'accrétion de Hikurangi.

Bien qu'une tectonique en « accrétion latérale » ait été évoquée dès 1993 [17], seuls 300 km de déplacement ont été reconnus sur les décrochements dextres orientaux de la côte est de l'ı̂le nord [10], qui décalent les structures transverses de l'Oligocène terminal–Miocène basal de la façade septentrionale de l'ı̂le. Les 300 km de déplacement se sont produits le long de décrochements, qui sont progressivement scellés par des sédiments du Miocène supérieur–Pliocène. De plus, les prolongements en mer de ces décrochements rejoignent le fossé de subduction de Hikurangi, au nord de l'extrémité septentrionale du prisme d'accrétion, là où la marge active passe d'un régime en accrétion à un régime en érosion tectonique [7]. Les décrochements de la côte est y sont tronqués par la surface de subduction et apparaissent clairement comme d'anciennes structures, désormais inactives.

3 Évolution proposée de la tectonique décrochante

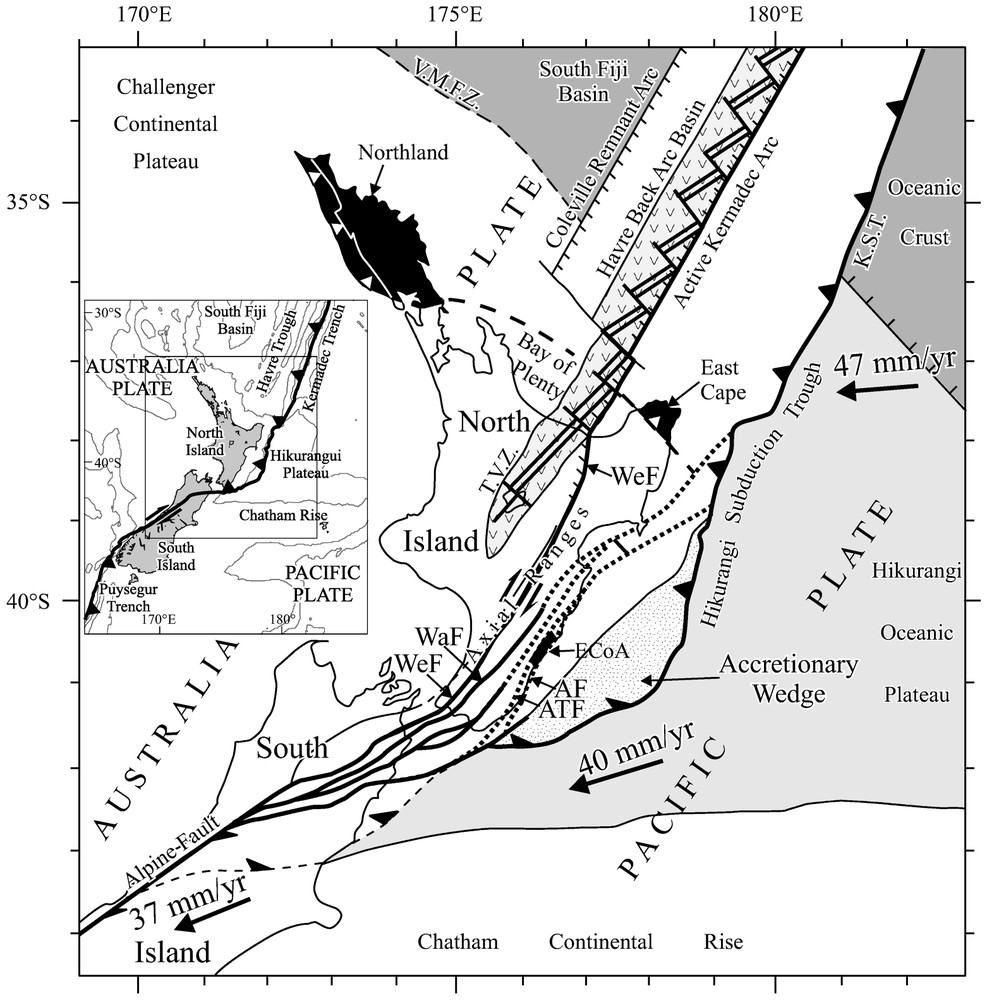

Les décrochements de la côte est de l'ı̂le nord, sur lesquels 300 km de déplacement ont été identifiés, ont commencé à être actifs au Burdigalien inférieur [1,10], et leur activité s'est très largement estompée à la fin du Pliocène. Ces faits sont en accord avec la répartition de la tectonique décrochante active, qui est localisée sur des accidents situés plus à l'ouest, le long des failles de Wellington et de Wairarapa (WeF & WaF de la Fig. 1). L'ensemble des décrochements de l'ı̂le nord de Nouvelle-Zélande dessine une « queue de cheval », pouvant correspondre à la distribution et l'amortissement, en direction, des déplacements parallèles à la marge à l'arrière de la zone de subduction.

Geodynamic pattern of North Island, New Zealand. White areas are of continental and arc lithosphere. Light grey area corresponds to thickened oceanic lithosphere. Light grey area with V pattern is the active volcanic zone of the back-arc domain. Dark grey areas are underlain by oceanic lithosphere. Black areas image material obducted along the north coast (Northland and East Cape), then dragged along the east coast (East Coast Allochthon: ECoA). Heavy solid lines are major active faults (WeF: Wellington Fault, WaF: Wairarapa Fault). Heavy dotted lines are faults with decreasing or no activity. V.M.F.Z.: Vening Meinesz Fracture Zone, T.V.Z.: Taupo Volcanic Zone, K.S.T.: Kermadec Subduction Trench. Wrench faulting occurred first from Early Miocene to Early Pliocene in the fore-arc domain, east of the Axial Ranges, at the easternmost fault splays of the ‘horse tail’ northern extension of the Alpine Fault. It is transferred since Late Pliocene to the obliquely opening back-arc domain along the westernmost fault branches that cross the Axial Ranges, which are the westernmost part of the Hikurangi accretionary prism backstop.

Schéma géodynamique de l'ı̂le nord de Nouvelle-Zélande. La zone blanche représente les domaines lithosphériques continentaux et d'arc. La zone en gris clair représente la zone de lithosphère océanique épaissie. La zone gris clair avec un figuré en V est la zone de volcanisme actif du domaine arrière-arc. Les zones en gris foncé correspondent aux domaines de lithosphère océanique; les zones en noir figurent les terrains obductés au Miocène basal sur la marge nord de l'ı̂le (Northland et East Cape), puis entraı̂nés le long de la côte est (ECoA). Les lignes épaisses représentent les principales failles actives (WeF : faille de Wellington, WaF : faille de Wairarapa). Les lignes pointillées épaisses sont des failles dont l'activité est faible ou nulle. V.M.F.Z : zone de fracture de Vening Meinesz, T.V.Z. : zone volcanique de Taupo, K.S.T. : fosse de subduction de Kermadec. La tectonique décrochante est d'abord apparue, du Miocène inférieur au Pliocène, dans le domaine avant-arc à l'est des Axial Ranges, le long des failles les plus orientales « de la queue de cheval » qui prolonge la faille Alpine vers le nord. Elle est transférée à partir du Pliocène supérieur dans le domaine en ouverture oblique de l'arrière-arc par l'intermédiaire de failles franchissant les Axial Ranges, lesquelles représentent la partie la plus occidentale du butoir du prisme d'accrétion de Hikurangi.

Cependant, dans cette « queue de cheval », les branches orientales du dispositif ne sont plus le lieu d'une intense activité tectonique, alors que les branches occidentales sont extrêmement actives depuis le Pliocène terminal [22]. La déformation décrochante n'a donc pas cessé dans le butoir du prisme d'accrétion de Hikurangi, mais elle a migré vers l'ouest au cours du Pliocène. De plus, on note que, du sud vers le nord, les failles décrochantes actives occidentales quittent le domaine avant-arc pour rejoindre le domaine arrière-arc et atteindre la côte nord au niveau de la Bay of Plenty (Fig. 1). Au point où s'effectue la connexion, c'est-à-dire à la limite entre la Taupo Volcanic Zone et le bassin du Havre méridional, le mouvement, de purement décrochant, devient transtensif.

En mer, des levés bathymétriques et sismiques menés dans le bassin arrière-arc du Havre [11,26] ont confirmé l'obliquité systématique du grain structural du fond du bassin par rapport à son axe [5,28,29]. Les données géophysiques recueillies montrent que l'ouverture oblique du bassin à partir du Pliocène [28] a été suivie à terre au Quaternaire basal par les premières manifestations volcaniques associées [27]. L'ouverture, qui s'effectue par rifting, est associée à des structures transverses à valeur de failles transformantes, qui viennent conforter le schéma d'une ouverture oblique associant intimement extension et déplacement dextre. La connexion de failles décrochantes actives, comme la WeF, avec le bassin arrière-arc confirme donc le prolongement vers le nord-est du mouvement décrochant actuel, associé à la convergence oblique entre les plaques australienne et pacifique.

Le saut de la tectonique décrochante associée à la convergence oblique de la plaque pacifique sous la plaque australienne au droit de l'ı̂le nord de Nouvelle-Zélande s'effectue depuis le domaine avant-arc vers le domaine arrière-arc au cours du Pliocène. Le dispositif actuel en « queue de cheval » des décrochements dans l'ı̂le nord est donc essentiellement polyphasé et ne correspond pas à un amortissement en direction de la tectonique décrochante dans la large zone frontière. Au contraire, le saut de tectonique décrochante apparaı̂t associé à l'ouverture oblique au Pliocène du bassin arrière-arc, représenté par l'ensemble Taupo Volcanic Zone (TVZ) – bassin du Havre (HB). Le dispositif en « queue de cheval » des failles décrochantes de l'Ile nord traduit le blocage croissant vers le sud à la fois de l'ouverture du domaine arrière-arc et du transfert associé de la tectonique décrochante due à l'entrée en subduction du Plateau océanique de Hikurangi [8].

4 Conclusion

Nous proposons de considérer que l'ouverture à l'ouest, au Pliocène, d'un domaine de lithosphère amincie dans un bassin arrière-arc a créé des conditions mécaniquement plus favorables à l'implantation d'une nouvelle zone de tectonique décrochante, alors qu'au sud, la difficile subduction du plateau de Hikurangi sous l'ı̂le nord de Nouvelle-Zélande bloque progressivement, à la fois l'ouverture du domaine arrière-arc de la TVZ et le transfert de la tectonique décrochante vers ce domaine. L'un des résultats de cette modification structurale est l'individualisation, à partir du Pliocène supérieur, d'un bloc lithosphérique, de nature « arc volcanique » au nord (arc de Kermadec) et de nature continentale au sud (côte est de l'ı̂le nord), coulissant le long de la frontière entre les plaques australienne et pacifique.

1 Introduction

Among subduction zones, strictly frontal convergence is an end member of a widespread range of variable cases of oblique convergence. Depending mainly but not exclusively on increasing obliquity [6,18,21,23], part or all of the along strike component of inter-plates movement is taken up at specific locations at the back of the subduction trench within the leading edge of the overriding plate. Commonly this strain partitioning takes place in weak zones of the shallow lithosphere of the plate boundary system [6]. As a consequence, a major strike-slip fault or fault-zone develops parallel to the subduction trench that separates a narrow lithospheric wedge, which migrates sideways along the plate boundary on top of the down-going plate.

Such systems have been described in differing contexts depending on the nature and geometry [6,23], specially the dip angle, of the subducting plate. Basically, a thick and/or light subducting plate is tightly coupled with the overriding plate, which favours the occurrence of partitioning. Strike-slip faulting occurs just at the back of the accretionary prism in the Ryukyu archipelago [15]. It develops mostly in the fore-arc domain at the Mentawai Fault and in the Volcanic Arc domain at the Great Sumatra Fault in western Indonesia [2,12,19,20]. In the Philippines, the left-lateral Philippine Fault runs within the arc domain at mid-distance from two opposed verging subduction zones [24,25]. In southern Japan, owing to a flat subducting slab [14], transcurrent faulting occurs far inboard the overriding plate within the active volcanic arc and both volcanism and strike-slip tectonics develop at the back-arc basin's border. In northern Andes [13], the strike-slip component of plate displacement is typified by strike-slip fault that cut the leading edge of a continental overriding plate far behind the fore-arc. In opposition to the previous cases, the steeper subduction dip of a dense plate with associated trench retreat and back-arc opening provides, within the latter domain, a new zone of weak lithosphere liable to accommodate strike-slip faulting [6]. Surveys carried out in the Havre back-arc basin north of New Zealand [5,11] show that the basin is the loci of extensive tectonics associated with large dextral displacement of the arc-block relatively to the overriding plate.

In strain-partitioning patterns seen in plan view, the main alterations in wrench tectonic occurrences are driven by changes in orientation of the plate boundary relatively to the plate convergence vector [18]. This happens first where the plate boundary bends and eventually tends to parallel the plate vector giving the entire boundary a wrench fault aspect (i.e., northern Sumatra), or second where the relative rotation pole of the involved plates is located close from a rectilinear plate boundary. In the latter case, the plate convergence progressively becomes closer from trench normal with progressive dying out of wrench tectonics when moving away from the rotation pole. This happens at both southern [4,9,16] and northern terminations [1,3,7,11,28] of the dextral major Alpine Fault of New Zealand.

2 The problem of northeastern extension of strike-slip tectonics in North Island

The oblique convergence between the Pacific and Australian plates in and offshore North Island New Zealand raises additional questioning. Based on the offset of the Dun mountain peridotite belt, at least 500 km of dextral displacement are evidenced along the Alpine Fault trace in the South Island. This amount of finite displacement could even reach 800 km if the clockwise bending of the Dun Mountain associated to Rangitata orogeny (Triassic–Early Cretaceous) structures was to be considered. The northward increase in frontal convergence leads to slight decrease in wrench faulting to be expected along the northern splays of the Alpine Fault that extend within North Island.

Occurrence of wrench tectonics along the East Coast of the North Island, within the backstop of the Hikurangi accretionary prism, was referred to as ‘lateral accretion’ induced [17], based on dredges performed off the East Coast. Collected samples appeared to be similar to rocks of obducted series commonly known from Northland to East Cape along the northern coast of North Island. Field observations carried on in the East Coast [10] complementarily showed that the transverse-to-plate-boundary structures made of obducted Northland–Eastcape series that were emplaced from Latest Oligocene to Earliest Miocene underwent dextral displacement ranging up to 300 km along the East Coast of North Island: East Coast Allochthon (EcoA of Fig. 1). Nevertheless, this displacement does not meet the expected amount of translation inferred from observed marker offset in the South Island. Moreover the 300 km displacement is observed within the fore-arc domain on easternmost strike-slip faults branches, the Adam's Tinui and Akitio faults (ATF & AF) that join northeastward the subduction trench north of the northern tip of the Hikurangi accretionary prism. At this junction site, the inner wall of the trench is being tectonically eroded and the offshore extensions of the faults are cut by the subduction surface. Clearly, the 300-km displacement that occurred on the strike-slip faults predate the present-day movement at the plate boundary. Consistently field surveys support that the ATF and AF show very little present activity if any compared to the western fault splays of the ‘horse tail’, namely the Wellington and Wairarapa faults (WeF & WaF). Thus, at this stage, the question remains open of where the present-day northeastern extension of large wrench tectonic occurs. Similarly, possible dying out of strike-slip structures within North Island cannot be ruled out.

3 Proposed development of strike-slip tectonics

Regarding this problem, additional information is provided both by field and offshore data. The easternmost strike-slip fault branches (ATF & AF) show very large offsets in pre-Burdigalian rocks, although younger sediments are much less displaced. Also the oldest sediments that bury subordinate splays of the ATF are Burdigalian in age. Therefore, inception of movement along the eastern ATF and AF is assigned an Early Burdigalian age [1,10]. According to observed lessening of displacements and progressive burial of the faults by younger Miocene then Pliocene sediments, most of the eastern faults activity ceased during Pliocene times. The fact that these faults only have been preserved at the backstop of the Hikurangi accretionary prism and disappear northeastward where the margin becomes of tectonic erosion type [7] supports that they are ‘old’ Early Miocene features. Segments of the ATF and AF can be occasionally reactivated, but the faults are no more the loci of large movements. This is in complete agreement with the present day distribution of strike-slip activity on the WeF and WaF to the western North Island.

The western splays of the ‘horse tail’ structure (WeF & WaF) became most active since Latest Pliocene times [22], which therefore substantiate the ‘horse tail’ structure of North Island that does not correspond to some kind of northward dying out of the dextral movement. Rather it supports a westward progressive transfer of tectonic activity from the ATF and AF to the WeF & WaF that commenced during Pliocene times. The major WeF diverges northwards from the horse tail structure and straddles the highest westernmost relieves of the prism deforming-backstop and eventually joins the back-arc domain at the Bay of Plenty coast (Fig. 1). This must be regarded together with the timing of the offshore HB development, which started to open at the beginning of Pliocene times [28] and was followed ashore by the first associated volcanic activity in the Earliest Quaternary. Surveys carried out in the HB [5,11,26,28,29] have shown the oblique-to-basin axis structural pattern of the seafloor, which is characterised by oblique rifting associated with transform-like transverse structures that both support the fact that basin opening was driven by dextral transtensive tectonics as far north as to 25 °S latitude.

The northward diverging set of strike-slip faults of the ‘horse tail’ pattern of North Island appears to be diachronous with two main stages of development. The first stage occurred to the east in the fore-arc domain and was most active prior to the onset of tectonic erosion at the northern Hikurangi Subduction Trough [8] as well as to the opening of the HB. The second stage corresponds to the transfer of strike-slip tectonics to the back-arc domain that was achieved in Latest Pliocene times with the connection of the WeF to the back-arc basin at the Bay of Plenty. It then developed concurrently with the Taupo volcanism in Late Pliocene to Quaternary times [27]. The newly opened back-arc domain appears to have provided better rheologic conditions, such as thinned and softened lithosphere for wrench tectonics relocation, in close association with rifting.

4 Conclusion

We propose the westerly jump of wrench tectonics from the fore-arc domain to the back-arc domain in North Island New Zealand was constrained by the development of the newly formed Taupo Volcanic Zone–Havre Basin back-arc domain. The opening of an increasingly thinning lithospheric domain progressively favoured the relocation of the wrench faulting within the back-arc domain. In opposition, the entrance of the buoyant Hikurangi Plateau in the subduction zone impeded southwards the opening of the Taupo-Volcanic Zone and the possibility of wrench tectonics transfer towards the back-arc domain.

As a result of the wrench tectonics jump is a newly Late-Pliocene-created lithospheric block that is presently being dragged southwestwards along the leading edge of the overriding Australian Plate. This block is of arc nature where it underlies the active Kermadec volcanic arc to the north and extends southward ashore where it is composed of continental material below the uplifted East Cape and East Coast of North Island.

Acknowledgements

The present work was performed in the frame of the France–New Zealand cooperative program. Financial support was provided by C.N.R.S, France, I.G.N.S, New Zealand and the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Publication n∘ 599 de Géosciences Azur.