Version française abrégée

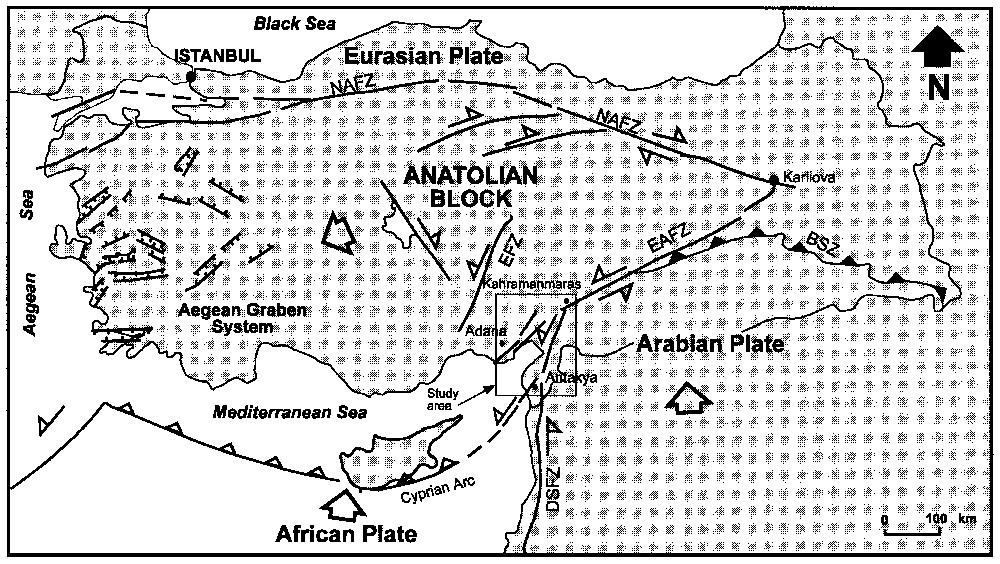

La région d'étude est affectée par la déformation liée aux mouvements entre les plaques Arabique, Africaine et Eurasiatique (représentée par l'Anatolie) [42]. Actuellement (Fig. 1), le déplacement de l'Arabie vers le nord donne lieu à l'extrusion de l'Anatolie vers l'ouest le long de ses bordures, à savoir, au nord, par la faille Nord-Anatolienne (FNA) et, à l'est, par la faille Est-Anatolienne (EAF). La FNA, décrochement dextre, et la EAF, décrochement sénestre, se rencontrent à proximité de Karliova, dans l'Est de la Turquie, d'où la EAF s'étend sur approximativement 500 km de long vers le sud-ouest jusqu'à Turkoglu (Kahramanmaras). À partir de Turkoglu (Fig. 2), bien que la continuation de l'EAF reste toujours discutable, elle semble se divise en deux segments : (1) un segment orienté NE–SW, qui est représenté par la faille de Karatas–Osmaniye, qui s'allonge le long de la montagne de Misis entre Adana et Kahramanmaras, limitant le bassin d'Adana au Sud-Ouest (secteur i) – notons que cette faille n'est pas très bien visible entre Osmaniye et Turkoglu – ; (2) un segment orienté NNE–SSW, représenté par la faille d'Amanos entre Turkoglu et Antakya (secteur ii). La faille d'Amanos est considérée comme la bordure de plaques entre l'Arabie et l'Anatolie [33] ; la faille de Karatas–Osmaniye est donc considérée comme un accident intracontinental.

Sketch map of the eastern Mediterranean tectonic framework.

Carte tectonique simplifiée de la Méditerranée orientale.

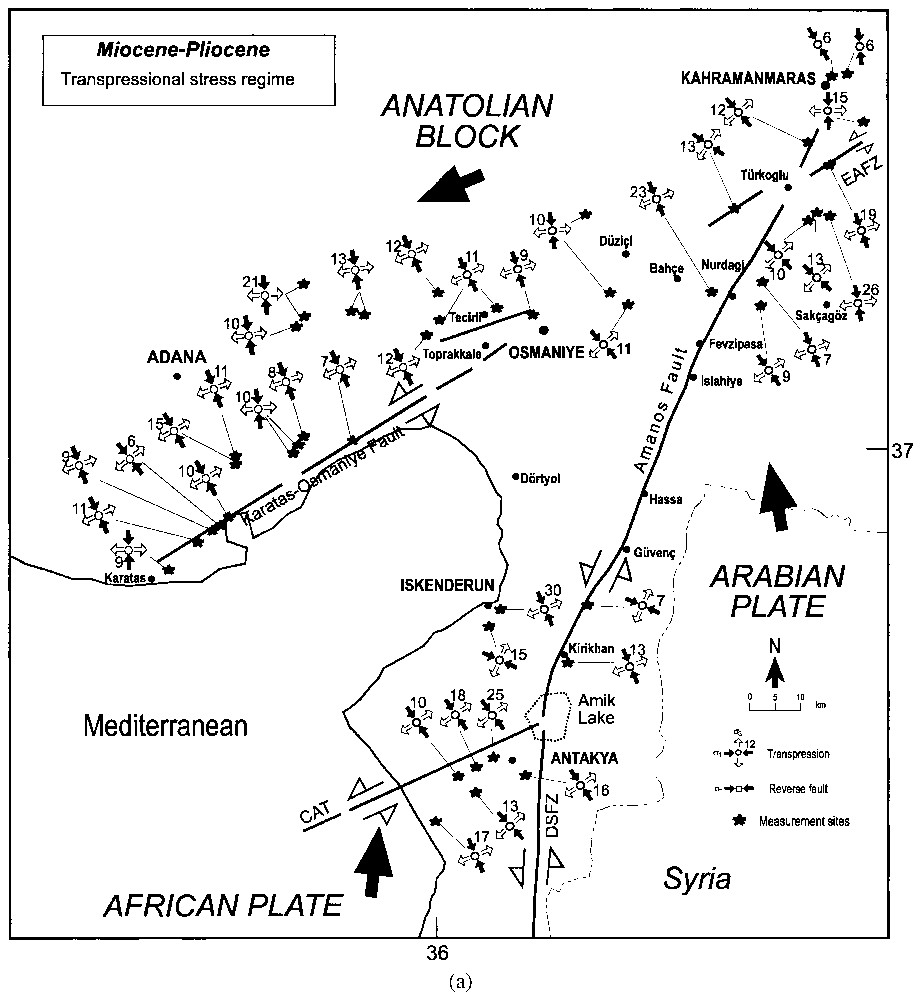

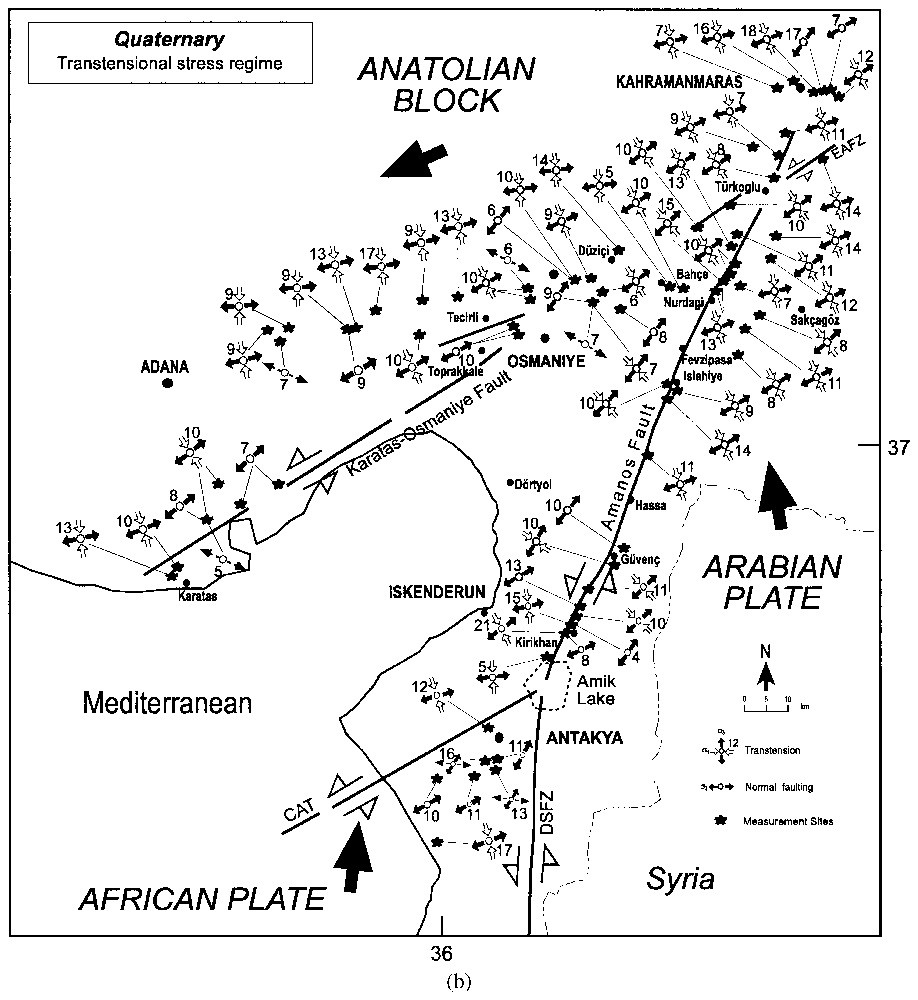

Simplified tectonic map of the study area. Azimuths of σ3 (extensional stress) and σ1 (compressional stress) axes for the Late Cenozoic stress regimes are shown. Stars show locations of kinematic sites. (a) refers to the Mio-Pliocene transpressional strike-slip stress regime deduced from the fault slip measurements; (b) refers to the Quaternary transtensional strike-slip regime deduced from the fault slip measurements.

Carte tectonique simplifiée de la région d'étude. Les azimuts de σ3 (contrainte extensive) et de σ1 (contrainte compressive) pour le régime de contraintes du Cénozoı̈que supérieur sont donnés. Les étoiles montrent les localisations des sites cinématiques. (a) Résultats relatifs au régime de transpression du Mio-Pliocène ; (b) résultats relatifs aux régimes de transtension et normal du Quaternaire.

Le mouvement relatif, vers le nord, de la plaque Africaine est associé à une subduction de la Méditerranée orientale le long des arcs Hellénique et Chypriote [3,13,14,24]. Le long de deux arcs, la subduction est documentée par les études séismologiques, gravimétriques, bathymétriques et les profils sismiques [12,20,35]. L'analyse cinématique structurale suggère une variation des déformations entre la compression et l'extension et confirme l'existence de structures extensives dans la plaque chevauchante, c'est-à-dire dans le domaine Egéen et Ouest-Anatolien [3,26,45], dans les bassins d'Adana et de Cilicia, au nord de Chypre [11,20]. La tectonique en extension est attribuée au retrait (roll back) de la plaque plongeante le long de l'arc Chypriote [14,30,36]. Le retrait de la plaque plongeante donne lieu à l'extension dans la plaque chevauchante, qui est notée dans l'arc Hellénique [3,26], sur l'arc Chypriote [14,30], sur la cordillère des Andes [25] et sur les arcs Éoliens [23].

L'objectif principal de cette synthèse est de mettre en évidence, ensemble, tous les résultats, alors qu'ils ne sont présentés que partiellement dans les références [30–32], afin de proposer une synthèse de l'évolution de l'état de contraintes du Mio-Pliocène à l'Actuel dans une vaste région située entre les provinces d'Adana, Antakya et Kahramanmaras, où les plaques Africaine et Arabique rencontrent le bloc Anatolien. L'étude de la cinématique des failles qui affectent les formations miocènes jusqu'à plio-quaternaires et anté-néogènes de la région a permis de reconnaı̂tre les états de contrainte, du Néogène supérieur jusqu'à l'Actuel. En utilisant la méthode proposée par [10], l'inversion des mécanismes au foyer des séismes peu profonds a permis de calculer l'état de contrainte qui règne actuellement dans la région d'étude. Les mesures effectuées sur les populations de failles ont été traitées numériquement par la méthode d'inversion de [9], pour déterminer le déviateur responsable de leur mouvement.

L'analyse de la cinématique des failles révèle un changement significatif de l'état de contrainte du Mio-Pliocène à l'Actuel. Ce changement s'est réalisé du régime décrochant à composante inverse (transpression) au régime décrochant à composante normale (transtension). La transpression est caractérisée par des directions NNW–SSE (N345±9°E) de σ1 et ENE–WSW (N255±10°E) de σ3 dans le secteur (i) et NW–SE (N151±11°E) de σ1 et NE–SW (N59±12°E) de σ3 dans le secteur (ii). Les rapports des contraintes (R) sont 0.75 et 0.76 pour les secteurs (i) et (ii), respectivement [31,32]. La transtension est caractérisée par des directions NNW–SSE (N163±12°E) de σ1 et ENE–WSW (N255±9°E) de σ3 dans le secteur (i) et NW–SE (N154±8°E) de σ1 et NE–SW (N243±8°E) de σ3 dans le secteur (ii). Les rapports des contraintes (R) sont 0,20 et 0,17 pour les secteurs (i) et (ii) respectivement [31,32]. Le manque de connaissance géologique ne permet malheureusement pas de définir avec précision à quelle époque se produit le changement de cinématique. Cependant, les travaux précédents [6,11,30] nous permettent d'estimer que le changement au cours du temps s'est effectué pendant le Quaternaire. La transtension avec l'extension de direction ENE–WSW [N243°E, secteur (i)] et NE–SW [N66°E, secteur (ii)] de σ3 est actuellement active, comme le confirme l'inversion des mécanismes au foyer des séismes. Les résultats indiquent également un changement spatial de l'état de contraintes entre les secteurs (i) et (ii).

Les deux régimes tectoniques, significatifs à l'échelle régionale, produisent un mouvement sénestre sur la faille majeure Est-Anatolienne qui semble être représentée dans le Sud-Ouest par la faille de Karatas–Osmaniye, considérée comme intracontinentale, le long de la montagne de Misis de direction NE–SW entre Karatas et Osmaniye et, dans le Sud, par la faille de Amanos, considérée comme une limite de plaques allongée le long de la montagne d'Amanos (c'est-à-dire la vallée de Karasu) entre Antakya et Kahramanmaras.

En effet, les régimes de contraintes résultent d'influences à la fois du phénomène de subduction le long de l'arc Chypriote au sud, de la collision continentale à l'est et de l'extrusion de l'Anatolie vers l'ouest. Le changement de régime tectonique, significatif à l'échelle régionale, est probablement lié à une modification de la géodynamique associée à la plaque plongeante le long de l'arc Chypriote, en Méditerranée extrême-orientale.

1 Introduction

The most important objective of this paper is to show all data together, which are beforehand represented partly in [30–32] in order to put forward a synthesis of the Mio-Pliocene to present-day stress regime evolution in an important large area where meet Arabia, Africa and Anatolia. The study area includes Adana, Kahramanmaras and Antakya provinces at northeastern corner of the Eastern Mediterranean (Fig. 1).

The stress regimes were obtained by inversion of slip-vectors measured on minor and major fault planes affecting Miocene to Plio-Quaternary deposits as well as the pre-Neogene units and by inversion of focal mechanisms of shallow earthquakes.

2 Tectonic/geodynamic setting

The deformation pattern related to the Arabian/ African plates and the Anatolian block (part of the Eurasian plate) is distributed in a large area of southeastern Turkey, included in the Adana, Kahramanmaras and Antakya Provinces. The northward drift of Arabia produces a continental collision having caused a thickening of the crust in eastern Turkey and compressional deformation along the Bitlis–Zagros fold and thrust belt (i.e., Bitlis Suture Zone, BSZ, Fig. 1) [39]. Contemporaneously, this northward motion with respect to the Eurasian plate is responsible for the westward extrusion of the Anatolian block along its northern and eastern boundaries, the dextral North-Anatolian Fault Zone (NAFZ) and sinistral East-Anatolian Fault Zone (EAFZ), respectively [24,42]. The left-lateral displacement on the EAFZ has been identified from seismological, geological and kinematic studies [24,40,43]. Both the historical and instrumental period catalogues indicate that this area is located within a seismically active region [15,16].

Northward motion of the African plate results in subduction in the Eastern Mediterranean along both the Hellenic and Cyprus arcs [4,13,24,44]. Along both arcs, the subduction processes have been documented by bathymetric and seismological studies [22,24,37]. Structural kinematic analysis suggests a variation of deformation style between compression and extension and confirms the existence of extensional structures in the overriding plate, i.e., in the Aegean domain and Western Anatolia [25,45], in the north Cyprus, Adana and Cilician Basins [12,20]. The extensional tectonics is attributed to rollback of the Mediterranean subducted slab along the Cyprus Arc [14,30,36]. The slab retreat is inferred to be a dominant control on crustal extension, i.e., a decrease of the compressional horizontal stress and/or an increase of the extensional horizontal stress on the overriding plate, which signs the Hellenic Arc [3,27], the Cyprus Arc [14,30], in the Andean Cordillera [25], and Eolian Arcs [23].

Two major strike-slip faults, the right-lateral NAFZ and left-lateral EAFZ, meet each other near Karliova in the East of Turkey, from where the EAFZ elongates southwestward about 500 km long down to the Kahramanmaras region (at Turkoglu). From there, its continuation is still in debate: the EAF may extend to the Amik Basin in the south [30,33,35,40], or to the Gulf of Iskenderun in the southwest [24]. Therefore, the southwestern part seems to affect a large area comprising the Misis Range, along which extends the Karatas–Osmaniye and Misis–Ceyhan faults. The EAFZ is represented by a southern branch, the Amanos Fault, between Turkoglu and Antakya [30,35,40,44], and a southwestern branch, the Karatas–Osmaniye fault, although it is not clearly expressed between Osmaniye and Kahramanmaras [31,32]. The Amanos fault has been considered as a plate boundary between the Anatolian block and the Arabian plate [33]. However, the Karatas–Osmaniye Fault can be interpreted as an intra-continental accident.

3 Fault kinematic analysis

3.1 Methodology: inversions of fault-slip datasets to determine the paleostress state

The main objective of this work is to define the Mio-Pliocene to present-day states of stress in southeastern Anatolia and their probable significances in relation to regional tectonic events. The methodology of fault kinematics studies is to determine paleostress fields and demonstrate temporal and/or spatial changes [3,5,6,25–27,29,30,34]. In order to determine the stress fields responsible for the Late Cenozoic deformations in the investigated area, we have carried out a quantitative inversion of distinct families of slip data determined at each individual site, using the method originally proposed by [9]. This inversion method assumes that the slip represented by the striation(s) occurs in the direction of the resolved shear stress (τ) on each fault plane, the fault plane being a pre-existing fracture. Inversion computes a mean best-fitting deviatoric stress tensor from a set of striated faults by minimizing the angular deviation between a predicted slip-vector (maximum shear, τ) and the observed striation(s) (e.g., [1,9]). Similar inversion methodologies, all based on minimization of the ‘deviation’ angle have been developed by a number of investigators for robust datasets including a wide variety of slip vectors and fault plane orientations (see references in [27]). Inversion results include the orientation (azimuth and plunge) of the principal stress axes of a mean deviatoric stress tensor as well as a ‘stress ratio’ [R=(σ2−σ1)/(σ3−σ1)]. Principal stress axes, σ1, σ2 and σ3 correspond to the compressional, intermediate and extensional deviatoric stress axes, respectively, while the R ratio is a linear quantity describing the relative stress magnitude, where (σ1)+(σ2)+(σ3)=0. The results of the stress inversion are generally considered reliable if 80% of the deviation angles (angle between the calculated slip-vector τ and the striation s) are less than 20°. As defined, the stress ratio varies between two end-member uniaxial stress states, that is R=0 when σ2=σ1 and R=1 when σ2=σ3. In a strike-slip-faulting stress regime (where vertical stress σv=σ2, maximum horizontal stress σHmax=σ1, and minimum horizontal stress σHmin=σ3), the R=0 end-member corresponds to a stress state transitional to normal faulting (extensional regime), in which σHmax=σv, whereas the R=1 end-member represents a stress state transitional to thrust faulting (compressional regime), in which σHmin=σv. For R-values close to 0 or to 1, the near-transitional (that is near uniaxial when 0.85<R<1 and 0<R<0.15) stress states require only minor fluctuations in stress magnitude to change from one stress regime to the other, that is, from a strike-slip to an extensional regime, or from a strike-slip to a compressional regime [5].

3.2 Inversion of seismic slip-vector data sets to determine the present-day stress state

We computed the state of stress responsible for present-day faulting from the population of focal mechanisms of earthquakes that occurred in the whole area. We used an inversion statistical method proposed by [10], which allows calculation of the best mean fitting stress state from a population of focal mechanisms by selecting one of two nodal planes as the seismic fault plane. Recently alternative inversion method is proposed by [2] without selecting seismic-fault. The selection can be made by using computer analysis or from the co-seismic rupture or from the spatial epicenter distribution of the aftershock sequence. Indeed, one of the focal mechanism solutions (i.e., nodal planes) is the seismic fault slip vector, which is in agreement with the principal stress axes. It is possible to compute the seismic fault slip following the model proposed by [7]. This method requires knowledge of the seismic slip-vectors and consequently the selection of the preferred seismic fault plane from each couple of nodal planes. This selection is possible by computation: one of the two slip-vectors of a focal mechanism solution is the seismic slip vector in agreement with the principal stress axes. For this slip-vector the computed a stress ratio (R) is such that 0<R<1 [7]. If one of the two nodal planes satisfies these conditions, the other does not satisfy, unless the two nodal planes intersect each other along a principal stress axis [9].

4 Results

4.1 Late Cenozoic stress regimes

Fault slip chronologies inversions of the slip-vectors [30–32] indicate the strike-slip, reverse and normal faultings that correspond to regionally and/or locally significant stress regimes along the Misis Range (sub-area i), along the Amanos Range (sub-area ii) and around Amik basin. In this study we include results of all measurements on fault planes affecting the Miocene to Quaternary as well as pre-Neogene deposits. The data reported in this study provide evidence of strike-slip faulting affecting mainly Miocene and Plio-Quaternary deposits and indicate a temporal change within the strike-slip regime from reverse component to normal component faulting. Thus, this change probably marked between transpression and transtension. The inversion result of each site is given in detail by [30–32].

4.2 The reverse-component strike-slip regime

Results of the inversion of all the fault slip-vector datasets belonging to this deformation stage consistently indicate a strike-slip faulting stress regime with a mean NNW- and northwest-trending maximum horizontal stress (σHmax=σ1) axis and a mean ENE- and northeast-trending minimum horizontal stress (σHmin=σ3) axis in areas (i) and (ii), respectively. The calculated mean deviator of the Fisher statistic yields a regionally significant stress state characterized by a σ1 axis trending N345±9°E and a σ3 axis N255±10°E, both axes having plunge of 4° for sub-area (i) and these values are N151±11°E and N59±12°E, with plunge of 6° and 1° respectively for sub-area (ii). This shows a spatial change in σ1 and σ3 axes directions from sub-area (i) to sub-area (ii). For both areas the computed mean R-values of 0.75 and 0.76 indicate that the regional stress regime is transpressional [31,32]. This means that the σHmin axis is close to magnitude to σv, indicating a regional strike-slip regime close to the transition to a reverse faulting regime. This is consistent with the local reverse faulting observed in several places (Fig. 2a). At these localities, brittle deformation shows reverse oblique-slip striations that agree with approximately NNW-trending compression, for which the inversions yield reverse-faulting stress states (σv=σ3). Individual and combined sites with numbers of fault-slip vectors of each site near the σ1 and σ3 directions are shown on a map of Fig. 2a. This was probably active during the transpressional period which produced or reactivated the Misis structural highs. The Miocene-Pliocene compressive structures (reverse faults and folds) observed in sub-area (i) along the Misis range by [19] and in sub-area (ii) along Amanos range by [12,18,21] occurred strongly during this transpressional deformation stage.

4.3 The normal-component strike-slip regime

Slip-vectors measured at several sites in both areas indicate a young normal-component strike-slip deformation stage post-dating the old transpression. Evidence for this younger strike-slip stress regime is recorded by slip-vectors on faults, which affect Mesozoic limestone and Mio-Pliocene deposits as well as more recent deposits. Results of the inversion of all the fault slip-vector data sets belonging to this deformation stage consistently indicate a strike-slip faulting stress regime with a mean NNW- and northeast-trending maximum horizontal stress (σHmax=σ1) axis and a mean ENE- and northeast-trending minimum horizontal stress (σHmin=σ3) axis for sub-areas (i) and (ii), respectively. The calculated mean deviator of the Fisher statistic yields a regionally significant stress state characterized by a σ1 axis trending N163±12°E and N255±9°E and a σ3 axis N154±8°E, and N243±8°E with plunge of 1° for sub-areas (i) and (ii), respectively. This shows a spatial change in σ1 and σ3 directions from sub-area (i) to sub-area (ii). The mean R-values are 0.20 and 0.17, indicating that the regional stress regime is transtensional [31,32]. This means that the σHmax axis is close in magnitude to σv, indicating a regional strike-slip regime close to the transition to a normal faulting regime. Thus, the normal faulting that resulted from ENE- and northeast-trending extension is computed at several sites. Individual and combined sites with numbers of fault-slip vectors of each site near the σ1 and σ3 directions are shown on the map in Fig. 2b. We have also measured normal faulting slip-vectors characterizing another extensional regime with an approximately ESE-trending σ3 axis, near Antakya and near Osmaniye towns (Fig. 2b). This ESE-trending extension seems to be subsequent to the regionally significant transtensional stress regime and is probably of only locally significance. Nevertheless, the GPS results indicate the existence of this extensional direction [4].

5 Present-day stress regime

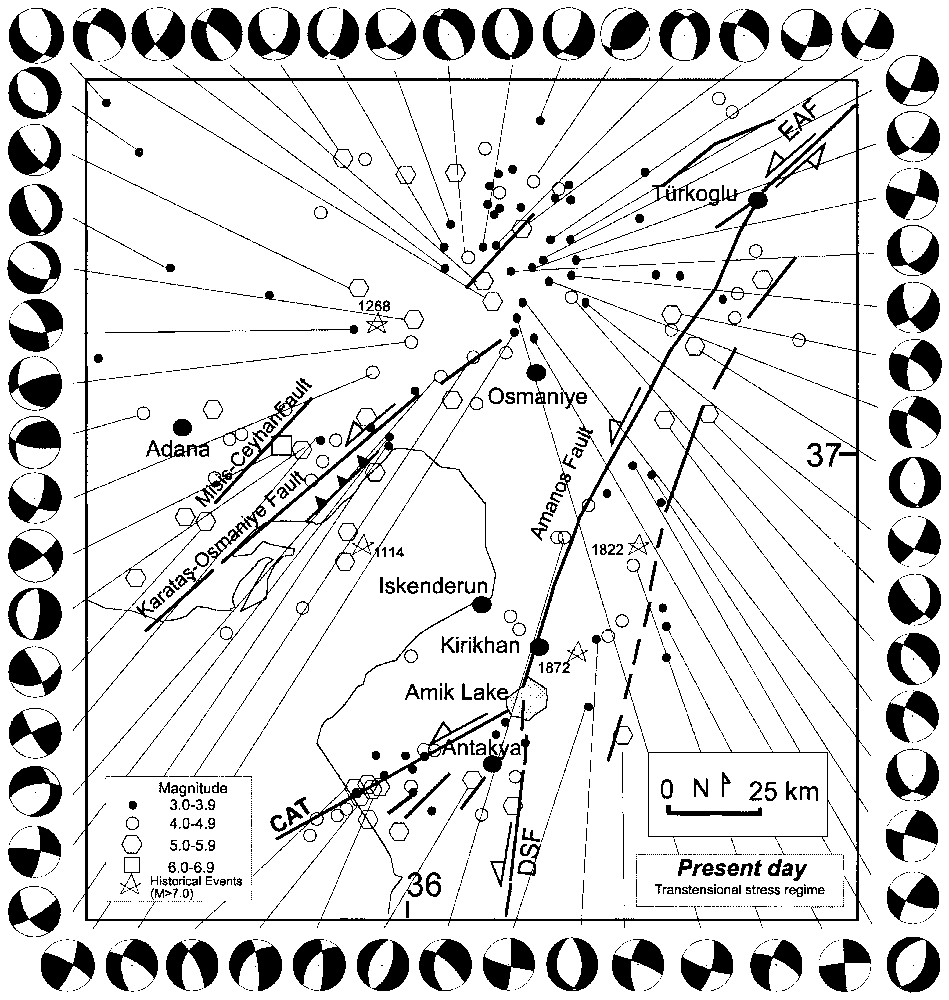

The available focal mechanisms for earthquakes of magnitude 2.9 to 6.2 for a period between 1967 and 2001 are shown in Fig. 3. We have used 59 focal mechanisms corresponding to the events located within the whole area provided by references [8,16,28] and the Harvard CMT catalogue (http://www.seismology.harvard.edu/CMTsearch). The inversions of focal mechanisms yield two stress deviators: strike-slip and extension in the whole area. Inversion of selected seismic fault-slip sets of strike-slip stress regime gives NNW (N5°W)-trending σ1 and ENE (N83°E)-trending σ3 axes for the area between Adana and Osmaniye (sub-area i) [31], and northwest (N24°W)-trending σ1 and northeast (N66°E)-trending σ3 axes in the Antakya, Osmaniye and Kahramanmaras Provinces (sub-area ii) [32]. The computed stress-ratio values (R) are 0.43 and 0.36, respectively for sub-areas (i) and (ii), indicating that this stress regime is transtensional. The inversions of other selected seismic fault slip sets give a normal faulting stress regime (σ1=σv) with an ENE (N83°E)-trending σ3 axis in sub-area i and with a northeast (N69°E)-trending σ3 axis in sub-area ii [31,32], which is N51°E around the Amik Basin [30]. Thus, both strike-slip and extensional regimes deduced from inversions of the earthquake focal mechanisms confirm that the present-day stress regime is transtensional in the whole study area (Fig. 3).

Seismotectonic map of the study area and focal mechanisms of shallow earthquakes.

Carte séismotectonique de la région d'étude et mécanismes au foyer des séismes peu profonds.

Indeed, the inversions of the youngest slip-vectors recorded by brittle deformation, the seismic fault-slips deduced from the focal mechanisms of shallow earthquakes lead to conclude that the regionally significant recent Quaternary to present-day stress regime is transtensional. The deviatoric stress directions change spatially from ENE-trending to northeast-trending σ3 axis along Misis Range [sub-area (i)] and Amanos Range [sub-area (ii)]. The transtensional regime acting in the study area involves both normal-component strike-slip and oblique normal faulting producing sinistral motion on Karatas–Osmaniye and Amanos faults, respectively.

6 Discussions and conclusion

The compressive structures (reverse faults and folds) during the Late Miocene–Pliocene, along the Misis structural highs [19] and along the Amanos Range [12,18,21] could have been produced or reactivated during transpressional deformation stage as a consequence of boundary forces, i.e., northward motions of the Arabian plate in the east and of the African plate in the southwest [24,36,42]. The younger transtensional stress regime is responsible for the extensional structures observed in southeastern Anatolia [19,20,35]. This extensional stress state was also indicated by [30] both focal mechanism and fault kinematic inversions around the Amik Basin (e.g., Antakya Provinces). The results show also that both regional significant stress states change spatially from sub-area (i) to sub-area (ii). Seismological data and analysis of SPOT XS imagery [33] indicate that the Quaternary Amik Basin is actually a triple junction area between sinistral Amanos Fault, Dead Sea Fault and Cyprus–Antakya Transform Fault (CAT, Figs. 2 and 3) representing boundaries of Arabia/Anatolia, Africa/Arabia and Anatolia/Africa, respectively.

Seismic and geological evidence along the eastern flanks of the Bay of Iskenderun [19] suggests that the Quaternary basalts and normal faults cut old thrust faults. Seismic profiles show the presence of normal faults bounding the Amik Basin [35], filled with Quaternary deposits [38,44]. The transtensional tectonic stress regime seems to extend over much larger areas including the EAFZ in Eastern Anatolia and implying that the lithosphere of Anatolia is subjected to extension [11]. This regional transtension to extension stress regime characterized by a southwest-trending (σ3) has prevailed since the Pleistocene [6] along the central North Anatolian Fault Zone. The configuration of the regional transtension to extension observed along the central and eastern North-Anatolian Fault Zone is not the response to the simple lateral westward extrusion but was also induced by boundary forces of Arabia-Anatolia collision and is rather due to the retreat of the Hellenic slab [6]. The correlation of previous studies allows us to estimate that the regional significant transtension is active since the Quaternary time [6,11,30,34].

The source of the variation in the horizontal stress magnitude, i.e., the decrease in the horizontal stress axis (σHmax) and/or by an increase in the vertical stress axis (σv) (equals σ2 in the strike-slip case and σ1 in the normal faulting case) in the overriding plate has resulted from the slab-pull force that has accompanied slab retreat above a subduction zone along the Cyprus Arc. The change between compressional/uplift/transpressional to transtensional/extensional tectonic regimes observed in southeastern Anatolia (e.g., [19,20]) can be explained by variations in the Mediterranean slab force from the Mio-Pliocene to the present day along the Cyprus Arc [14,36]. The slab-pull force is considered to be a major force in driving the plates and controlling the tectonics of an overriding plate above a subduction zone [17,40,41]. The tectonic regimes acting in the study area since the Mio-Pliocene seem to result from the coeval influence of boundary forces due to active Arabia/Anatolia continental collision in the northeast inducing the westward escape of Anatolia, and the easternmost Mediterranean subduction along the Cyprus Arc in the south. However, the change in the stress regimes evidenced by correlation of both our data and previous studies corresponds to variations in horizontal and/or vertical stress magnitudes probably in relation to geodynamic changes within the easternmost Mediterranean associated with the subducted slab along the Cyprus Arc.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by TUBITAK–YDABAG (project No. 100Y095) and Research Foundation of Cumhuriyet University (Projects n° M 121 and M 153). The authors would like to thank Prof. Dr Alastair Robertson (Edinburgh University) and Dr John Piper (Liverpool University) for their constructive comments and English that improved the earlier version of the text. The authors also would like to thank Prof. Dr Jacques Angelier (Paris-6 University) and Prof. Dr Jean Chorowicz (Paris-6 University) for their very constructive criticisms that improved the manuscript.