Version française abrégée

1 Introduction

La côte pacifique du Mexique a fonctionné comme une zone de convergence depuis le Crétacé supérieur. Dans l'État du Sonora, ce magmatisme de subduction est représenté par des batholites granitiques datés entre 90 et 40 Ma [11,14,30,39,46] et, plus à l'est, par le vaste plateau ignimbritique oligocène de la Sierra Madre occidentale (SMO). La morphologie actuelle en Basin and Range du Nord-Ouest du Mexique a été façonnée par différentes phases tectoniques. Entre 30 et 28 Ma, des basaltes de type trapps se mettent en place dans la partie nord et centre de la SMO [5,8,13,29]. La phase d'étirement principale débute au Miocène [3,14,27,29,37]. Elle se traduit par la formation de bassins endoréiques d'orientation NNW–SSE [7,14,27], dans lesquels s'accumulent les molasses continentales de la formation Báucarit [9,33]. Du Miocène supérieur à l'Actuel, la tectonique distensive, particulièrement active dans la partie centrale et occidentale du Sonora, conduit à un amincissement progressif de la lithosphère et à l'ouverture du golfe de Californie [2,25,42]. La mise en évidence du caractère hyperalcalin de l'ignimbrite d'Hermosillo apporte de nouveaux éléments sur l'âge et les mécanismes de la rupture continentale.

2 Contexte géologique

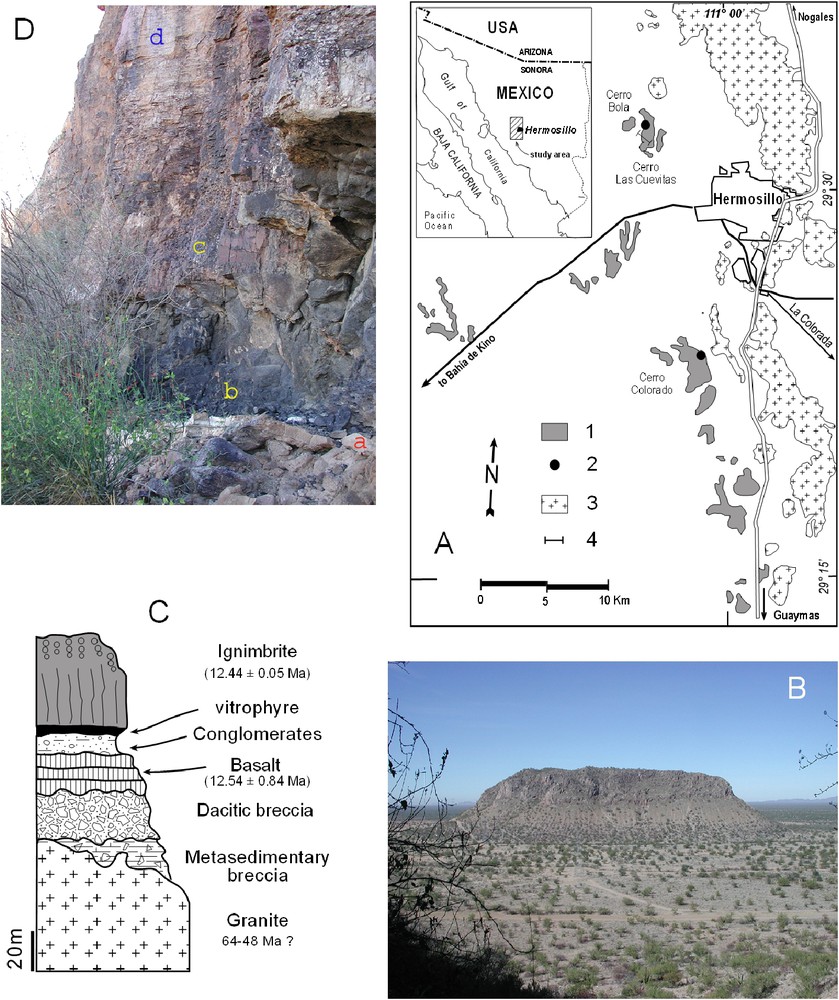

L'ignimbrite de la région d'Hermosillo (Fig. 1A) présente des caractéristiques morphologiques (Fig. 1B), minéralogiques et chimiques qui la différencient des empilements de roches acides calco-alcalines de la SMO [13,26]. Elle correspond à une seule unité de refroidissement, d'environ 50 m d'épaisseur (Fig. 1D). Un niveau vitrophyrique noir est souvent observable à la base (b, Fig. 1D). Le vitrophyre est directement au contact de grès et conglomérats (a) qui occupent le fond des paléovallées. Il passe, vers le haut, à un niveau riche en lithophyses (c), puis à une ignimbrite gris violacé (d) très soudée, à fiammes aplaties blanches. La partie supérieure est silicifiée et dévitrifiée consécutivement à la circulation de fluides ayant accompagné le dégazage de la coulée. Des basaltes affleurent parfois sous cette ignimbrite, sans discordance majeure (Fig. 1C). Ils recouvrent une brèche de dacite à amphibole. De telles roches ont été datées entre et [30,31] dans la Sierra Santa Ursula, à 100 km au sud d'Hermosillo. Cet arc miocène est représenté par des faciès proximaux en Sonora, mais principalement distaux en basse Californie [30,35,42]. Enfin, localement, affleurent des granites à grain fin correspondant au toit du batholite d'Hermosillo [28].

Middle Miocene ignimbrite of the Hermosillo region. (A) Location of the ignimbrite outcrops; (1) ignimbrite; (2) location of dated samples; (3) granitic batholith; (4) location of the stratigraphic column. (B) Cerro Bola view from the east. (C) Composite stratigraphic column at Cerro Las Cuevitas. (D) Different lithofacies of the ignimbrite observed north of Cerro Las Cuevitas: (a) basal conglomerate; (b) vitrophyre; (c) transitional zone; (d) eutaxitic ignimbrite (more explanations in the text).

Localisation de la séquence volcanique Miocène moyen de la région d'Hermosillo. (A) Carte des affleurements d'ignimbrite. (B) Vue du Cerro Bola depuis l'est. (C) Log stratigraphique du Cerro Las Cuevitas ; (D) Différents faciès constituant l'unité ignimbritique au nord du Cerro Las Cuevitas (explications dans le texte).

3 Géochronologie

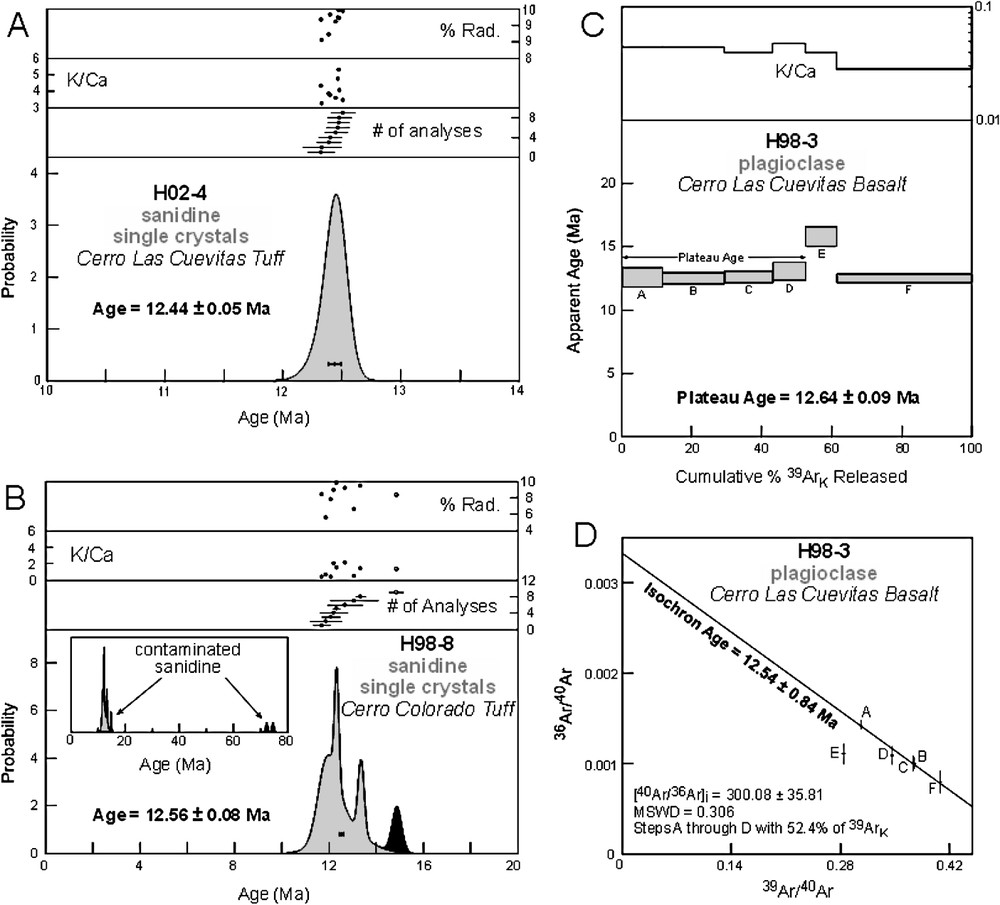

Deux échantillons d'ignimbrite et un basalte ont été datés par la méthode 40Ar/39Ar (Fig. 2 et Tableau 1). Les échantillons ont été irradiés sur le réacteur TRIGA de l'U.S. Geological Survey, en utilisant comme minéraux de référence la sanidine FCT-3 [6,16] et l'amphibole MMhb-1 [1,10] selon la méthode décrite par [40]. La fusion laser a été utilisée pour les sanidines, le chauffage par paliers pour le plagioclase [17]. Les données obtenues ont été traitées avec les programmes de calculs de [12,15], en utilisant les constantes de désintégration préconisées par [41]. Les âges obtenus sur les sanidines des vitrophyres des Cerros Las Cuevitas et Colorado (Fig. 1A) sont identiques ( et , Tableau 1). Dans l'échantillon H98-8 (Cerro Colorado), trois feldspaths ont donné des âges de 72–74 Ma. Il s'agit de toute évidence de xénocristaux provenant de roches plutoniques laramiennes. Le basalte a fourni un âge plateau de sur plagioclase. Les données géochronologiques mettent ainsi en évidence l'existence d'un épisode volcanique de type bimodal au Miocène moyen, dans la région d'Hermosillo.

Graphic representations of 40Ar/39Ar laser and step-heating geochronology data for Middle Miocene ignimbrite and a basalt from the Hermosillo region, Sonora.

Représentation graphique des mesures géochronologiques 40Ar/39Ar pour l'ignimbrite et le basalte du Miocène moyen de la région d'Hermosillo, Sonora.

40Ar/39Ar dates on Middle Miocene basalt and ignimbrite from Hermosillo

Ages 40Ar/39Ar d'un basalte et de l'ignimbrite du Miocène moyen de la région d'Hermosillo

| Step or laser hole | Temp. (°C) | % 39Ar of total | Radiogenic yield (%) | 39Ark (Moles × 10−12) | 40Ar∗ | Apparent | Error | |

| 39Ark | K/Ca | K/Cl age (Ma) | (Ma) | |||||

| H02-4 | Ignimbrite | Single-crystal sanidine total fusion | J = 0.003891 ± 0.35% | #139KD25 | ||||

| 3 | t.f. | n.a. | 96.7 | 0.085015 | 1.762 | 4.3 | 132 | 12.33±0.09 |

| 1 | t.f. | n.a. | 90.4 | 0.046605 | 1.763 | 3.2 | 110 | 12.33±0.15 |

| 8 | t.f. | n.a. | 92.2 | 0.208911 | 1.772 | 3.8 | 113 | 12.39±0.08 |

| 10 | t.f. | n.a. | 98.1 | 0.274483 | 1.773 | 3.8 | 136 | 12.41±0.07 |

| 2 | t.f. | n.a. | 95.9 | 0.227212 | 1.780 | 3.6 | 105 | 12.45±0.08 |

| 6 | t.f. | n.a. | 97.3 | 0.182446 | 1.783 | 4.7 | 134 | 12.47±0.08 |

| 9 | t.f. | n.a. | 99.6 | 0.308271 | 1.784 | 5.3 | 98 | 12.48±0.07 |

| 7 | t.f. | n.a. | 97.2 | 0.135114 | 1.784 | 4.1 | 104 | 12.48±0.08 |

| 4 | t.f. | n.a. | 99.2 | 0.150355 | 1.789 | 3.4 | 128 | 12.51±0.08 |

| Weighted mean age = | ||||||||

| H98-8 | Ignimbrite | Single-crystal sanidine total fusion | J = 0.003895 ± 0.35% | #138KD25 | ||||

| 5 | t.f. | n.a. | 84.1 | 0.021463 | 1.673 | 4.1 | 79 | 11.72±0.28 |

| 6 | t.f. | n.a. | 55.6 | 0.011008 | 1.698 | 6.1 | 92 | 11.89±0.58 |

| 8 | t.f. | n.a. | 78.3 | 0.020943 | 1.728 | 4.0 | 88 | 12.10±0.30 |

| 10 | t.f. | n.a. | 89.5 | 0.012320 | 1.747 | 20.1 | 129 | 12.23±0.46 |

| 9 | t.f. | n.a. | 97.8 | 0.097989 | 1.761 | 14.8 | 130 | 12.33±0.09 |

| 11 | t.f. | n.a. | 91.7 | 0.008146 | 1.813 | 21.0 | 118 | 12.69±0.66 |

| 7 | t.f. | n.a. | 66.2 | 0.006114 | 1.870 | 4.7 | 64 | 13.09±0.91 |

| 1 | t.f. | n.a. | 94.7 | 0.057248 | 1.909 | 14.6 | 134 | 13.36±0.13 |

| 2 | t.f. | n.a. | 83.1 | 0.034265 | 2.126 | 13.6 | 118 | 14.88 ± 0.21 |

| 3 | t.f. | n.a. | 98.4 | 0.044185 | 10.486 | 55.6 | 109 | 72.21 ± 0.43 |

| 4 | t.f. | n.a. | 99.6 | 0.053654 | 10.821 | 31.9 | 134 | 74.47 ± 0.44 |

| Weighted mean age = | ||||||||

| H98-3 | Basalt | Plagioclase | J = 0.004751 ± 0.25% | wt = 239.3 mg | #63KD28 | |||

| A | 900 | 11.5 | 57.8 | 0.038908 | 1.885 | 0.04 | 529 | 12.62±0.37 |

| B | 1000 | 17.8 | 70.2 | 0.060341 | 1.870 | 0.04 | 872 | 12.52±0.20 |

| C | 1100 | 13.9 | 70.3 | 0.047269 | 1.884 | 0.04 | 504 | 12.61±0.25 |

| D | 1200 | 9.2 | 67.6 | 0.031313 | 1.952 | 0.05 | 34 | 13.06±0.35 |

| E | 1300 | 9.0 | 67.2 | 0.030364 | 2.368 | 0.04 | 204 | 15.84±0.40 |

| F | 1450 | 38.6 | 76.5 | 0.131028 | 1.872 | 0.03 | 915 | 12.53±0.16 |

| Total gas | 100.0 | 70.7 | 0.339223 | 1.927 | 0.04 | 661 | 12.90 | |

| 52.42% of gas on plateau in 900 through 1200 steps | Plateau age = |

4 Pétrographie et minéralogie

L'ignimbrite d'Hermosillo est pauvre en phénocristaux et en xénolites. Les minéraux les plus abondants sont des feldspaths alcalins sodiques. Leur composition évolue depuis de l'anorthose (Ab72-62Or20-33) jusqu'à de la sanidine sodique (Ab59-48Or35-51, Fig. 3). Les minéraux ferromagnésiens sont représentés par du pyroxène de couleur verte, légèrement pléochroïque. Il s'agit de ferroaugite (Wo41-43En7-9Fs48-52) [32]. Les pyroxènes plus magnésiens trouvés dans l'un des échantillons (H96–6) sont des xénocristaux (Fig. 3). De la fayalite (Fa96) est aussi présente, mais elle est souvent remplacée par des produits d'oxydation rougeâtres. Les minéraux opaques sont de la titanomagnétite (13 à 17% de TiO2). Du zircon (0,5 mm) est associé à ces oxydes ferro-titanés. Le quartz n'est présent que comme produit de dévitrification dans les fiammes. La matrice vitreuse n'est conservée que dans les niveaux vitrophyriques. L'association minéralogique observée dans l'ignimbrite miocène d'Hermosillo est typique de roches acides hyperalcalines [19,21].

Plot of feldspar, pyroxene and olivine compositions of the Hermosillo basalt and peralkaline ignimbrite. Black dots: basalt; empty squares: peralkaline ignimbrite; grey squares: xenocrysts in the peralkaline ignimbrite.

Composition des feldspaths, des pyroxènes et des olivines du basalte et de l'ignimbrite hyperalcaline de la région d'Hermosillo. Points noirs : basalte ; carrés blancs : ignimbrite hyperalcaline ; carrés gris : xénocristaux dans l'ignimbrite.

5 Géochimie

Huit échantillons d'ignimbrite et deux de basalte ont été analysés par ICP-OES pour les majeurs et par ICP-MS pour les traces. Les analyses chimiques soulignent (1) le caractère transitionnel des basaltes (riches en titane, pauvres en silice et en alumine, riches en fer et légèrement enrichis en terres rares légères), (2) la nature rhyolitique des ignimbrites . Ces dernières sont pauvres en alumine et riches en alcalins. Trois échantillons ont un rapport (Na2O + K2O)mole/(Al2O3)mole compris entre 1,01 et 1,12 et possèdent de ce fait de l'aegyrine normative (Tableau 2). L'ignimbrite de la région d'Hermosillo est, d'après les rapports FeOt/Al2O3 [18,19] et quartz normatif/ferromagnésiens [21], une comendite.

Major and trace element data on Middle Miocene basalt and ignimbrite from Hermosillo. PI = Peralkaline index [(Na2O + K2O)(mole)/Al2O3(mole)]

Analyses chimiques (majeurs et traces) des basaltes et de 1'ignimbrite du Miocène Moyen de la région d'Hermosillo. PI = Indice d'hyperalcalinité [(Na2O + K2O)(mole)/Al2O3(mole)]

| H96-1 | H96-2 | H95-13a | H95-13b | H96-61 | H2-94 | H3-94 | H98-5 | H98-7 | H98-8 | |

| SiO2 | 47.31 | 47.69 | 73.12 | 76.43 | 74.98 | 74.66 | 72.88 | 74.14 | 76.14 | 73.26 |

| TiO2 | 2.60 | 2.51 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| Al2O3 | 15.55 | 15.37 | 12.45 | 12.36 | 12.37 | 12.53 | 12.20 | 12.40 | 11.83 | 12.31 |

| Fe2O3 | 6.29 | 7.36 | 1.20 | 1.70 | 1.42 | 1.40 | 0.77 | 0.75 | 1.52 | 0.85 |

| FeO | 7.15 | 5.90 | 0.66 | 0.08 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.83 | 0.92 | 0.34 | 0.79 |

| MnO | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| MgO | 5.59 | 5.94 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| CaO | 9.10 | 8.60 | 0.76 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.52 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.52 |

| Na2O | 3.57 | 3.34 | 3.85 | 3.90 | 4.27 | 5.28 | 5.23 | 3.88 | 3.68 | 3.89 |

| K2O | 0.85 | 0.70 | 4.25 | 4.55 | 5.09 | 4.95 | 4.53 | 4.41 | 4.60 | 4.28 |

| P2O5 | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| H2O+ | 0.23 | 0.41 | 2.47 | 0.42 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 2.88 | 2.98 | 0.55 | 3.64 |

| H2O− | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Total | 99.30 | 98.79 | 99.37 | 100.53 | 99.76 | 100.25 | 100.37 | 100.22 | 99.46 | 99.85 |

| PI | 0.88 | 0.92 | 1.01 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.90 | ||

| Rb | 12 | 3 | 196 | 185 | 191 | 180 | 180 | 178 | 189 | |

| Sr | 471 | 450 | 72 | 25 | 3 | 17 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 18 |

| Ba | 370 | 319 | 88 | 45 | 35 | 71 | 53 | 39 | 50 | 34 |

| Co | 46 | 51 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Cu | 31 | 36 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Cr | 54 | 59 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 23 | 6 |

| Ni | 37 | 41 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 3 |

| V | 270 | 271 | 12 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 11 | 3 |

| Zn | 144 | 125 | 90 | 78 | 53 | 65 | 86 | 81 | 66 | 84 |

| Zr | 254 | 242 | 275 | 304 | 384 | 340 | 304 | 332 | 333 | 313 |

| Y | 42 | 40 | 52 | 62 | 57 | 59 | 56 | 54 | 49 | 51 |

| Mb | 21 | 18 | 22 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 22 | 22 | 21 | 20 |

| H96-1 | H96-61 | H2-94 | H3-94 | H98-5 | H98-8 | |||||

| La | 24.5 | 51.0 | 55.5 | 54.5 | 56.5 | 55.0 | ||||

| Ce | 55.5 | 114.0 | 118.0 | 117.5 | 118.0 | 117.5 | ||||

| Pr | 7.4 | 13.3 | 14.5 | 13.5 | 13.8 | 14.0 | ||||

| Nd | 31.5 | 48.0 | 53.0 | 49.0 | 51.5 | 51.5 | ||||

| Sm | 7.5 | 9.8 | 11.0 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 10.8 | ||||

| Eu | 2.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||||

| Gd | 7.9 | 9.2 | 10.7 | 10.2 | 10.6 | 10.9 | ||||

| Tb | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | ||||

| Dy | 6.6 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 9.7 | 9.3 | 9.9 | ||||

| Ho | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.9 | ||||

| Er | 3.8 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 5.4 | ||||

| Tm | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | ||||

| Yb | 3.9 | 5.0 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 6.1 | ||||

| Lu | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | ||||

| Cs | 0.2 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 6 | ||||

| Th | <1 | 25 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 25 | ||||

| Ta | 0.5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||

| U | 0.5 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||||

| Pb | <5 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 20 | ||||

| Hf | 7 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 |

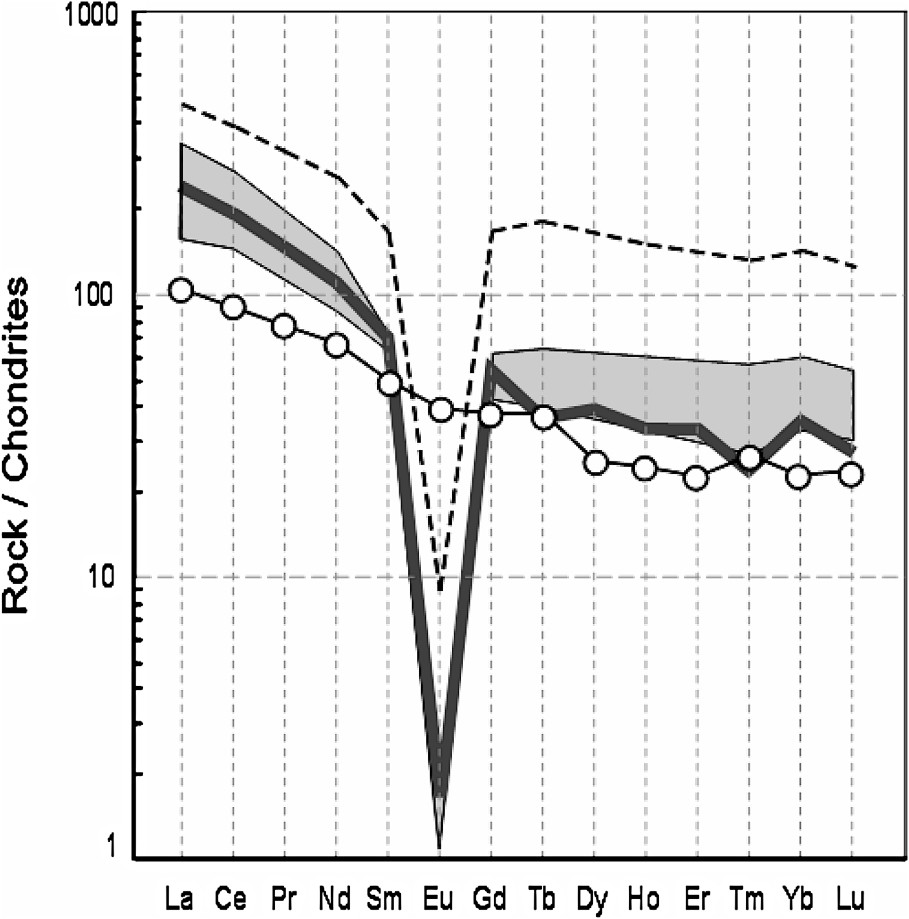

Les spectres de terres rares sont identiques pour les cinq roches analysées : enrichissement régulier en LREE, une forte anomalie négative en Eu et un tracé plat pour les HREE (Fig. 4). Les rapports (La/Yb)N sont compris entre 6 et 7. L'ignimbrite d'Hermosillo a une signature chimique semblable à celle des rhyolites hyperalcalines quaternaires de la région de Guadalajara, liées à la fracturation du bloc de Jalisco [23,24]. Celles du rift Est-Africain [22] sont plus riches en Nb, Ta et Zr.

Chondrite normalized rare earth element patterns for the Hermosillo basalt and peralkaline ignimbrite. Normalizing values from [44]. Empty dots: basalt; grey line: pattern for the 5 analysed ignimbrites; dashed line Naivasha ignimbrite (Kenya rift) [22]; light-grey field: peralkaline rhyolites from La Primavera [23].

Spectres de terres rares d'un basalte et de l'ignimbrite hyperalcaline de la région d'Hermosillo. Valeurs de normalisation d'après [44]. Points blancs : basalte ; ligne grise : spectre correspondant aux cinq ignimbrites analysées ; ligne en pointillés : ignimbrite de Naivasha (rift du Kenya) [22] ; champ gris clair : rhyolites hyperalcalines de La Primavera [23].

Les liquides hyperalcalins sont généralement interprétés comme le résultat (1) d'un processus de cristallisation fractionnée avec assimilation de croûte continentale [38] ou (2) de la fusion partielle de gabbro ou de basaltes sous-plaqués, suivie par un fractionnement à basse pression [4,45]. Le parallélisme observé dans les spectres de terres rares entre basalte et ignimbrite (Fig. 4) suggère un possible lien génétique entre les deux types de magmas.

6 Implications géodynamiques

Si l'existence d'un épisode ignimbritique Miocène moyen (14–10 Ma) est connue depuis longtemps [3,14,27,30,31] dans cette partie du Sonora, il a toujours été considéré comme un marqueur de la fin de la subduction. La reconnaissance du caractère hyperalcalin de l'ignimbrite de la région d'Hermosillo change fondamentalement la signification de cet épisode, car ce type de volcanisme est généralement associé à des structures de type rift [20]. Des ignimbrites de même nature et de même âge ont été trouvées, en Sonora dans la région du Pinacate [47], dans la partie centrale de l'État [48] et dans l'île Tiburón [35], mais aussi sur la côte nord-est de la péninsule de basse Californie [25,34,43]. Cet épisode hyperalcalin caractérise la formation d'un rift continental ou « proto-golfe ». Celui-ci a précédé l'ouverture océanique du golfe de Californie, qui n'est intervenue que lors de l'établissement d'une nouvelle frontière entre plaques Pacifique et Amérique du Nord [35,36].

1 Introduction

The Pacific coast of northwestern Mexico has been a convergent plate boundary since at least the mid-Cretaceous. In Sonora, subduction related magmatism is mostly represented by batholithic granitoids dated between 90 and 40 Ma [11,14,30,39,46] and, toward the east, by the widespread ignimbritic plateau of the Sierra Madre Occidental. SMO (Sierra Madre Occidental) takes shape during Late Eocene–Oligocene times as a consequence of the subduction of the Farallon Plate. Large-magnitude extensional processes have then progressively modelled the morphology of the region. A first episode of normal faulting resulted in the emplacement of trapp-like basalts (30–28 Ma) in the north-central part of the SMO [5,8,13,29]. Further Mid-Cenozoic extension disrupted the SMO volcanic plateau both to the east, in Sonora, and west in Chihuahua, giving rise to NNW–SSE-elongated endorheic fault-bounded hemi-grabens that were filled with clastic and volcanic deposits [7,14,27]. These continental sediments, known locally as Báucarit Formation (see [9,33]), have been emplaced during the Early Miocene [3,14,27,29,37]. From Miocene to the present, the tectonic regime has changed from a convergent to a transtensional plate margin as the Farallon plate fragmented and subduction ended. As a consequence, crustal extension has progressively migrated westward, in coastal Sonora, leading up finally to the opening of the Gulf of California rift system [2,25,42]. The peculiar peralkaline character of the Hermosillo ignimbrite provides new constraints on the age and mechanism of the continental break-up.

2 Geological setting

Ignimbritic outcrops studied in this paper correspond to mesas (Fig. 1B) scattered over an area of about in the vicinity of Hermosillo, Sonora (Fig. 1A). They figured on the geological maps of the region as undifferentiated Tertiary felsic volcanic rocks. These rocks show, however, clear differences in field and textural appearance, mineralogy, and geochemistry with the Oligo-Miocene ignimbrites forming the thick volcanic pile of the SMO to the east [13,26].

The Hermosillo ignimbrite is composed of a single cooling unit, 10–50-m thick, that present different lithofacies from bottom to top (Fig. 1D). A basal black vitrophyre (50-cm to 1-m thick) is commonly visible at the base of the cooling unit (b, Fig. 1D). The lower part of the vitrophyre grades to brown colour material at the contact with gravels and conglomerates (a) representing the bed of a palaeovalley filled by the pyroclastic flow. A transitional zone (20–40 cm) with abundant lithophysae partially filled with quartz (c) marks the limit between the black vitrophyre and the above layer, characterized by slower cooling rate but higher lithification. The central and thicker part of the ignimbritic unit consists of a welded grey-purplish eutaxitic ignimbrite (d). The highly flattened white fiammes give a laminated aspect to the rock. This part of the ignimbrite has been intensively quarried for use as building stone. The uppermost part of the pyroclastic flow is more vesicular and, locally, silicified and devitrified as a result of intense degassing during cooling. The whole unit presents irregular vertical jointing that formed massive columns. For the most part, the Hermosillo ignimbrite mesas are horizontal to gently tilted toward the west. The source area of the pyroclastic flow is difficult to constrain owing to the isolated nature of the different outcrops, but ignimbrite has clearly fossilized north–south valleys related with extensional tectonism.

At Cerro Las Cuevitas (Fig. 1A), ignimbrite rests upon olivine and clinopyroxene-rich basalts (Fig. 1C). Basalt and ignimbrite are structurally concordant; this suggests that they were emplaced in a short time interval. The basaltic flows, some metres thick, cover in turn dacitic breccias. Such hornblende- and clinopyroxene-phyric dacites are widespread in the western Sonoran Basin and Range Province. KAr ages obtained on similar rocks at Sierra Santa Ursula, 100 km to the south, gave ages on plagioclase between and [30,31]. Rocks belonging to this age group are proposed to be part of the Miocene subduction-related arc represented by proximal facies in Sonora and more distal ones in Baja California (Comundú Formation) [30,35,42]. As basement, below the volcanic sequences, crop out fine-grained plutonic rocks and dikes which constitute the roof of the 64–48-Ma-old Hermosillo batholithic complex [28].

3 40Ar/39Ar geochronology

Approximately 10 mg of sanidine from vitrophyres from Cerro Colorado (H98-8) and Cerro Las Cuevitas (H02-4), and 250 mg of plagioclase from a basalt flow (H98-3) underlying the Cerro Las Cuevitas vitrophyre were dated with 40Ar/39Ar geochronology (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Samples were irradiated in the central thimble facility at the TRIGA reactor (GSTR) at the U.S. Geological Survey, Denver, in packages KD25 (sanidine; 16 h) and KD28 (plagioclase; 15 h). The monitor mineral used in the both packages was Fish Canyon Tuff sanidine (FCT-3) with an age of 27.79 Ma [6,16] relative to MMhb-1 with an age of [1,10]. The type of irradiation container and the geometry of samples and standards are the ones described by [40].

All samples were analysed at the U.S. Geological Survey Thermochronology lab in Denver. Individual grains of sanidine were analysed using a MAP 216 mass spectrometer fitted with an electron multiplier using the 40Ar/39Ar laser fusion method of dating (CO2 laser). The plagioclase was analysed on a VG Isotopes Ltd., Model 1200 B Mass Spectrometer fitted with an electron multiplier using the 40Ar/39Ar step heating method of dating. For additional information on both analytical procedures, see [17].

The sanidine isotopic laser data were reduced using the computer program Mass Spec [12]. The argon isotopic step-heating data for the plagioclase were reduced using an updated version of the computer program ArAr∗ [15]. We used the decay constants recommended by [41]. Plateau ages are identified when three or more contiguous steps in the age spectrum agree in age, within the limits of analytical precision, and contain more than 50% of the 39Ar released from the sample.

The dates obtained on sanidine single crystals from Cerro Las Cuevitas and Cerro Colorado vitrophyres (Fig. 2A and B) correspond to the same age within limits of analytical error ( and , respectively). In sample H98-8 from Cerro Colorado, two individual crystals gave older ages of 72–74 Ma, most likely representing K-feldspar xenocrysts incorporated from the granitic basement during the emplacement of the ignimbrite. The basaltic flow underlying the ignimbrite at Cerro Las Cuevitas gives a plagioclase plateau age at (Fig. 2C), supported by an isochron age of (Fig. 2D), and that we interpret as the age of basaltic extrusion. Note that the ages of the basalt and of the vitrophyre from Cerro Las Cuevitas are indistinguishable at the two-sigma level of precision. However, the stratigraphic position of the basalt flow implies that the basalt is slightly older than the ignimbrite. These new geochronological constraints evidence the presence of a bimodal volcanic sequence in central Sonora during the Middle Miocene.

4 Petrology and mineralogy

This section will be mostly focused on the petrological description of the Middle Miocene ignimbrite as it is the key to identify it. This ignimbrite is slightly porphyritic (∼5% phenocrysts) and lithic-poor. Mineral compositions have been determined on seven polished thin sections using a Cameca SX100 electron microprobe fitted with five spectrometers at the ‘Service commun microsonde’ (University of Montpellier, France). The standard analytical procedure are 20 kV, 10 nA, 1-μm spot size, and integrated counting times ranging from 20 to 30 s. Alkalis were determined first to minimize Na loss during measurements.

Phenocrysts in the ignimbrite are dominantly sodic alkali feldspar with compositions ranging from anorthoclase (Ab72-62Or20-33) to sodic sanidine (Ab59-48Or35-51, Fig. 3). Rare oligoclase to andesine plagioclases have been also analysed (sample H00-1), but these crystals are obviously not in equilibrium with the liquid. Among the ferromagnesian phases, pale green clinopyroxene with weak pleochroism is the most conspicuous. These crystals are frequently slightly altered to yellowish clays toward the margin. Microprobe analyses show very homogeneous compositions (Wo41-43En7-9Fs48-52, Fig. 3), characterized by high FeOt (28%) and CaO (19–20%), low MgO (<3%) and Na2O (<0.5%) contents. Such compositions correspond to ferroaugite [32]. In sample H96-6, some pyroxenes have higher MgO contents (about 13%) but are, as the plagioclase, xenocrysts (Fig. 3). Fayalite occurs as small honey-coloured grains rimmed by reddish oxidation products. Chemical variation is small and the analyses plot very near the pure iron pole (Fa96, Fig. 3). The lack of biotite or amphibole can reflect high temperature and/or low water fugacity in these liquids. Titanomagnetite (13 to 17% TiO2) is scarce and commonly associated with small zircon (0.5 mm). Quartz is present, with K-feldspar, as a devitrification product in the fiammes but never as a phenocrystic phase. Fresh glass is only preserved in the vitrophyres. Microprobe data show lower values in sodium than in the whole rock analyses. The mineralogical association of the Middle Miocene ignimbrite from Hermosillo is therefore typical of oversaturated peralkaline liquids [19,21].

The basalts underlying the ignimbrite contain Mg-poor olivine (Fo56-50), augite (Wo41-45En43-38Fs14-18) and labradorite phenocrysts (An65-58). Scarce amphibole and phlogopite are present in the groundmass along with plagioclase and clinopyroxene (Fig. 3).

5 Geochemistry

Eight ignimbrite samples and two basalts were analysed for major and trace elements using ICP-OES, and another group of five ignimbrites was analysed by ICP-MS for REE and other trace elements (Table 2). Basalts from Cerro Las Cuevitas have a transitional character, with high TiO2 (>2.5%), low SiO2 and Al2O3 typical of alkaline magmas, but high total iron (>13%). These mafic lavas are yet differentiated as indicated by their low MgO, Ni and Cr concentrations. REE patterns are slightly enriched in LREE (Fig. 4).

Major element data show that ignimbrite samples are rhyolitic in composition (SiO2 ). They also have low Al2O3 (), about 1.8% total iron and moderately high total alkalis (Na2O + K2O = 8–10%). Three samples have peralkaline characteristics with acmite appearing in the norm (using analyses recalculated on an anhydrous basis) and (Na2O + K2O)(mole)/(Al2O3)(mole) ratios ranging from 1.01 to 1.12 (Table 2). The other five samples have lower sodium contents and therefore alkalis/alumina ratios lower than 1. The Hermosillo ignimbrite can be classified as comendite according to the FeOt/Al2O3 ratio [18,19] and the normative quartz versus total normative femics diagram [21]. It has relatively low concentrations in Zr, Nb, Ba, Sr and REEs for a peralkaline rock. The REE patterns are very similar for the five samples, showing a regular enrichment in LREE, a strong depletion in Eu and relatively flat but irregular HREE (Fig. 4). (La/Yb)N ratios are between 6 and 7 and (Tb/Yb)N next to 1.

The Hermosillo ignimbrite presents similar REE and trace element patterns as the Quaternary peralkaline rhyolites from the Guadalajara region (La Primavera caldera), related to rifting and ongoing separation of the Jalisco block [23,24]. They are quite different from the high-silica peralkaline liquids from the East African Rift [22], which are more enriched in Nb, Ta and Zr.

Peralkaline liquids are generally thought to be the result of (1) continuous fractional crystallization plus moderate assimilation starting from transitional basaltic parents ([38] and references therein) or (2) partial melting of mafic intrusive rocks or young underplated basalts followed by low-pressure fractionation and contamination [4,45]. It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss in detail the petrogenesis of the peralkaline ignimbrite from Hermosillo; nevertheless, parallelism in HREE and MREE concentrations between basalt and ignimbrite (Fig. 4) and similarities in trace element trends on spidergram (not shown) suggest some kind of genetic link between the transitional mafic lavas and the peralkaline oversaturated ignimbrite [48].

6 Geodynamic implications

An outburst of ignimbritic volcanism has long been recorded in central and coastal Sonora between 14 and 10 Ma, but it has always been considered an expression of late subduction processes [3,14,27,30,31]. The presence of a Middle Miocene peralkaline ignimbrite in the neighbourhood of Hermosillo changes drastically the way we interpret this volcanic episode since this kind of lavas is mostly encountered in continental rift environments [20,38]. The high-precision dating obtained on these rocks contributes moreover to define an important stratigraphic marker for the tectonic evolution of northwestern México. We have so recognized oversaturated peralkaline rocks in the Pinacate area [47] and other portions of central Sonora [48]. Besides, the ∼12-Ma-old ignimbrite named the San Felipe tuff [34,43] described in the Puertecitos region in northeastern Baja California [25] and correlated with horizons in Tiburón Island and coastal Sonora by [35], could be part of the same event. Such a flare-up of peralkaline acidic volcanism on the Sonoran margin at about 12 Ma is related to large-scale extension and lithosphere thinning that induced the formation of an intra-continental rift. This ‘proto-Gulf’ occurred before transtensional deformation and spreading operated in the Gulf area as a consequence of new Pacific–North America plate boundary motions [35,36].

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Mick Kunk from the U.S. Geological Survey in Denver for helping us with the 40Ar/39Ar geochronology. We also would like to thank Roy George, a former University of Colorado at Boulder student, for careful mineral separations.