Version française abrégée

Introduction et cadre géologique

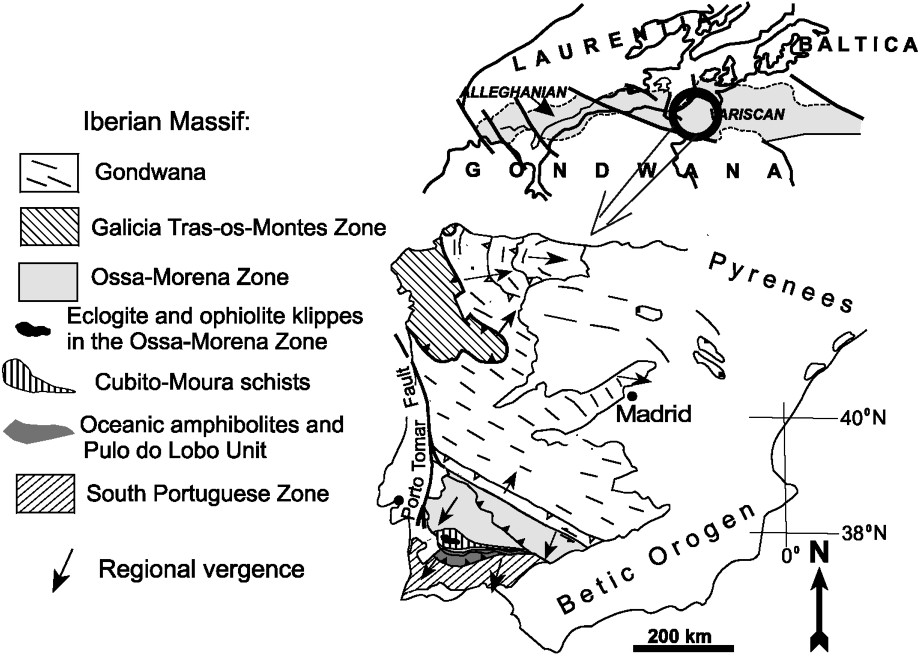

Dans le Sud-Ouest de l'Ibérie, la limite entre la zone d'Ossa Morena et la zone Sud-Portugaise est considérée comme la suture représentant la fermeture de l'océan Rhéïque (Fig. 1). Une unité amphibolitique d'affinité océanique marque ce contact tectonique majeur [4,5,9,11–13,25]. Un complexe de suture allochtone, moins bien connu, affleure au sud-ouest d'Ossa Morena (Fig. 1), au nord de la bande de l'amphibolite océanique, comprenant une large unité de métapélites (schistes de Cubito-Moura) et des affleurements épars d'éclogites et d'ophiolites en association avec des marbres [14]. La faible exposition et la déformation syn-collisionnelle sont parmi les raisons expliquant la connaissance insuffisante actuelle du complexe de la suture allochtone [2]. De plus, les techniques classiques de pétrologie métamorphique sont inadéquates pour détecter l'évolution HP des métapélites de grade métamorphique inférieur. Nous présentons ici les premiers résultats thermobarométriques des conditions

Simplified geological sketch of the Iberian Peninsula showing the main zones and the location of the Cubito–Moura schists.

Schéma géologique simplifié de la péninsule Ibérique, montrant les zones majeures et la localisation des schistes du Cubito–Moura.

Pétrographie et minéralogie

Les schistes de Cubito-Moura sont caractérisés par un clivage pénétratif de crénulation (S2), qui constitue leur foliation principale (Fig. 2). Une schistosité antérieure est préservée dans des domaines lenticulaires du clivage S2, principalement dans les lithologies riches en quartz (Fig. 3). Ces microstructures sont localement affectées par des plis asymétriques à vergence sud, associés à un clivage (S3) de plan axial. Les paragenèses minérales présentes dans les schistes sont des assemblages à haute variance, formées de mica blanc potassique, de chlorite, de quartz, de tourmaline, ± magnétite, ± ilménite, ± rutile, ± paragonite, ± chloritoïde, ± albite, ± apatite, ± xénotime. Des cavités fibreuses à albite, apatite et oxydes de fer sont fréquemment observées dans des veines de quartz plissées et transposées par la foliation principale S2 (Fig. 2A et B).

(A) Pre-S2 quartz vein with fibre-shaped voids (carpholite pseudomorphs ?). (B) The same type of quartz vein affected by a fold related to the main foliation (S2).

(A) Veine de quartz avec des cavités fibreuses, possibles pseudomorphes de la carpholite. (B) Les veines de quartz sont affectées par des plis serrés dont la crénulation S2 constitue le plan axial.

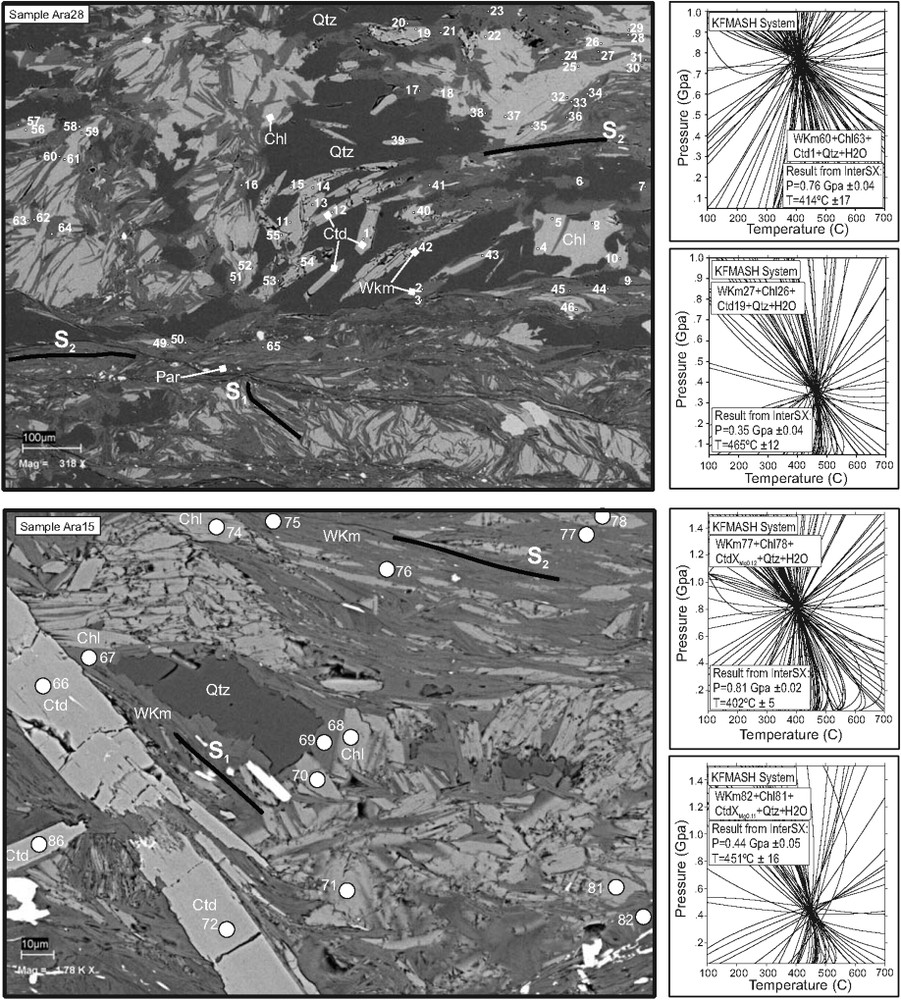

TWQ local equilibrium examples obtained from mica + chlorite + chloritoid parageneses. Notice the two foliations, S1 and S2, defined by mica, chlorite and chloritoid. Numbers in the SEM image show the analyses done on samples Ara28 and Ara15.

Équilibres TWEEQ pour les paragenèses mica–chlorite–chloritoïde. Remarquer les deux foliations S1 et S2 définies par ces minéraux. Les points des analyses faites sur les échantillons Ara28 et Ara15 sont indiqués sur l'image MEB.

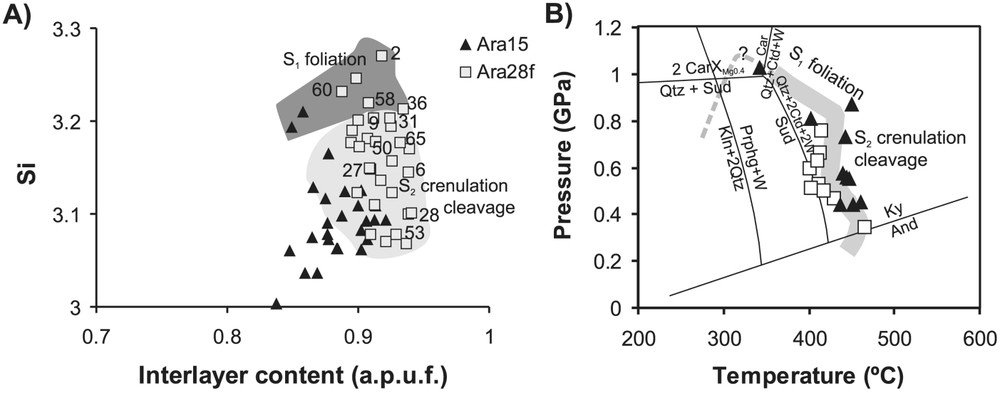

La composition des micas et des chlorites varie dans les différents domaines texturaux des échantillons étudiés. Dans les chlorites, une évolution générale est observée, depuis les compositions riches en clinochlore (0,11 Sud, 0,53 Clin et 0,36 Am), définissant S1, jusqu'à des compositions riches en amésite (0,17 Sud, 0,37 Clin et 0,46 Am) dans la crénulation S2. Les micas blancs potassiques (wKm) ont des teneurs en Si allant de 3,0 à 3,3 a.p.f.u. (Fig. 5A). La charge du cation interfoliaire, reliée à la substitution illitique, varie entre 0,84 et 0,94 (Fig. 5A). Les micas définissant la crénulation S2 montrent des teneurs en cation interfoliaire plus élevées et un taux en Si plus faible que ceux préservées dans les domaines S1.

(A) Composition of white K-micas in the sample studied expressed in a Si-Interlayer-Cation-content (IC) diagram. Notice the lower-Si and higher-IC content in the micas that define the main foliation relative to S1 micas. Numbers in sample Ara28 refer to analyses shown in Fig. 3. (B) TWQ results of the studied samples showing HP–LT conditions obtained for the S1 schistosity and later decompression during the growth of the S2 main foliation. Standard mineral abbreviations.

(A) Composition des micas-K, dans un diagramme des teneurs en Si et cations interfoliaires (IC). Notez la diminution de Si et l'augmentation de l'IC des micas S2 par rapport aux micas marquant S1. (B) Résultats TWEEQ pour l'échantillon étudié, montrant les conditions HP–BT obtenues pour la foliation S1 et la décompression postérieure durant le développement de la crénulation S2.

Estimations thermobarométriques

Les conditions

Les résultats thermobarométriques varient entre 340–370 °C à 1,0–0,9 GPa et 400–450 °C à 0,8–0,7 GPa pour les paragenèses mica–chlorite–chloritoïde définissant la foliation S1 (Figs. 3 et 5B). Les conditions obtenues pour S2 varient entre 400–450 °C à 0,8–0,7 GPa et 440–465 °C à 0,4–0,3 GPa (Figs. 3 et 5B).

Discussion et conclusions

L'équilibre local chlorite–micas–chloritoïde indique que les schistes de Cubito-Moura ont subi un événement métamorphique HP–BT à 340–450 °C et sous 1,0–0,7 GPa. Les résultats

1 Introduction and geological setting

Orogenic sutures are crucial for understanding the complexity of orogenic processes related to subduction, obduction, and collision. In the Iberian Variscan Massif, suture terranes crop out at different tectonic settings. In northwestern Iberia, suture terranes are included in allochtonous units (the Galicia-Trás-Os-Montes Zone [3]) of uncertain rooting. In southwest Iberia, the boundary between the Ossa-Morena and the South Portuguese Zones is thought to be a suture, attesting the closure of the Rheic Ocean (Fig. 1). An amphibolitic unit, namely the Beja-Acebuches Amphibolites, marks this major tectonic contact [4,5,11–13,25]. North of this amphibolitic unit, an allochtonous complex crops out. It includes a widespread metapelitic unit (Cubito-Moura schists) and discrete outcrops of eclogites and MORB metabasites, in association with marbles [14]. Poor exposure and overprinting related to syn-collisional deformation are the main reasons explaining the very recent characterization of this allochtonous suture-related complex [2]. Moreover, the unsuitability of classical techniques in metamorphic petrology to detect high-pressure evolution in low-grade metapelites has contributed to the limited knowledge of the tectonometamorphic evolution of this unit. We present here the first thermobarometric results obtained from the Cubito-Moura schists, which represent the metapelitic rocks of this suture-related complex. The

2 Petrography

The Cubito-Moura schists are characterized by a penetrative crenulation cleavage (S2) that forms their main foliation (Fig. 2A and B). A previous schistosity is preserved in lenticular domains of the S2 cleavage, especially in quartz-rich lithologies. S2 microstructures are locally folded by asymmetric south-vergent folds with an associated spaced axial-plane crenulation cleavage (S3). Mineral parageneses in the schists are high-variance assemblages formed by white K-mica, chlorite, quartz, tourmaline, magnetite, ± ilmenite, ± rutile, ± paragonite, ± chloritoid, ± albite, ± apatite, ± xenotime. Quartz veins transposed by the main foliation or in hinges of isoclinal folds associated with the main foliation show many fibre-shaped voids filled in with iron oxides or albite and apatite (Fig. 2A and B). No remains of the original fibrous mineral have been found. Albite and apatite commonly occur in late veins too, frequently retrogressing previous minerals. Paragonite and xenotime contents increase as well in the later fabrics, especially in post S2 shear zones.

In this paper, we present the results obtained from two schist samples bearing chlorite, phengite, paragonite, chloritoid, quartz, and ilmenite (samples Ara28 and Ara15 located at UTM coordinates: 29S0619346/4212974 and 29S0708988/4204897, respectively). Chloritoid is pre- to syn-kinematic with respect to the S2 foliation (Fig. 3). Chlorite-white K mica couples occur in both the S1 and S2 foliations, as well as in chloritoid pressure shadows. Late mica-chlorite growth is observed also retrogressing chloritoid crystals in the quartz-rich pre-S2 domains (Fig. 3).

3 Mineralogy

Chlorite, white K mica and chloritoid analyses were performed with a Cameca electron microprobe at the University of Granada (15 kV, 10 nA, PAP correction procedure) using Fe2O3 (Fe), MnTiO3 (Mn, Ti), diopside (Mg, Si), CaF2 (F), orthoclase (Al, K), anorthite (Ca) and albite (Na) as standards.

Chlorite has Si-contents ranging from 2.54 to 2.66 a.p.f.u. with

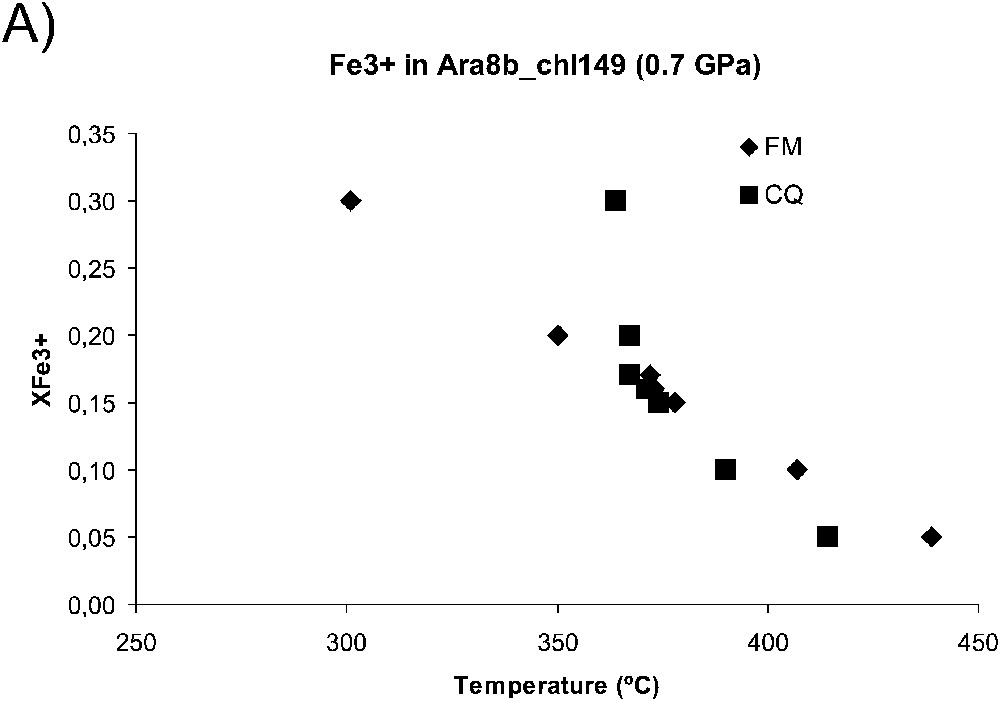

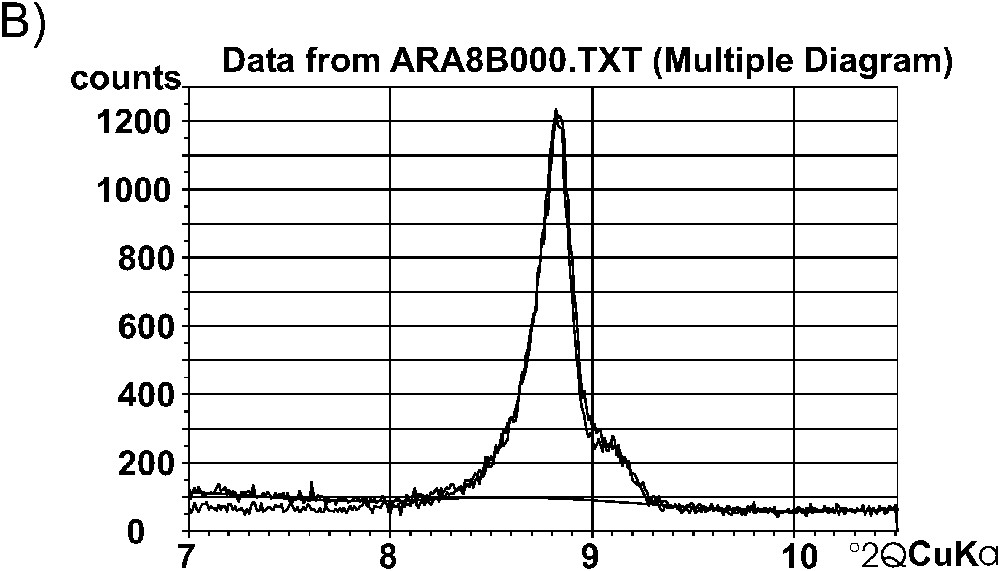

Fe3+ in chlorites has been estimated by using two different equilibriums. The first one is an ‘internal equilibrium’ involving Daph, Clin, Fe-Am and Mg-Am end-members. Since only three of these four end-members are independent, this ‘internal equilibrium’ must be satisfied to obtain the same solid-solution free energy calculated with either Clin, Daph, Fe- or Mg-Am [30]. The second equilibrium corresponds to Chl + Qtz (Clin + Sud = Mg-Am + Qtz + H2O) (Fig. 4A).

(A)

(A) Diagramme

White K-mica (wKm) has Si-contents ranging from 3.0 to 3.3 a.p.f.u. Variable Si-contents are generally interpreted in terms of Tschermak substitution alone (between celadonite and muscovite end-members), which is favoured by a pressure increase [19,20]. However, this pressure-dependent substitution is not straightforward, because white K-micas show variable interlayer-cation contents together with a departure from the celadonite–muscovite binary. Interlayer-cation deficiency (interlayer sum ranges from 0.84 to 0.94 in the sample studied) has been attributed to the illite substitution in muscovite (

Chloritoid shows

4 Local-equilibrium thermobarometry

Multi-equilibrium thermobarometry [6] is appropriate in the particular case of mica–chlorite pairs, because the equilibration of these minerals at varying P and T is mostly achieved by crystallisation/recrystallisation processes rather than by changing the composition of older grains by lattice diffusion. This is the case at the low-temperature fields of blueschist and greenschist facies metamorphism. Moreover, the relative sequence of crystallization of phyllosilicates can frequently be determined by microstructural criteria. Thus, using chlorite–white K-mica pairs defining different microstructures in a metamorphic rock, one can determine the

The thermobarometric results for sample Ara28 are of 380–440 °C at 0.8–07 GPa using mica–chlorite–chloritoid paragenesis defining the S1 foliation (Figs. 3 and 5B). The conditions obtained from the paragenesis related to the S2 crenulation cleavage range from 375–425 °C at 0.6–0.7 GPa to 440–465 °C at 0.3–0.4 GPa (Figs. 3 and 5B).

5 Discussion and conclusions

Chlorite–mica–chloritoid local equilibriums indicate that the Cubito-Moura schists underwent HP–LT metamorphism during the growth of their S1 schistosity that developed during heating and slight decompression between conditions of 340–370 °C at 1.0–0.9 GPa and 400–450 °C at 0.8–0.7 GPa. The S2 main foliation developed during isothermal decompression, followed by slight heating during further decompression, from 400–450 °C at 0.8 to 0.5 GPa, to 440–465 °C at 0.3–0.4 GPa (Fig. 5B). The

During HP–LT metamorphism, the Cubito-Moura schists underwent a similar metamorphic gradient as the one observed in the eclogites of the southern Ossa-Morena Zone, though in these latter higher pressure conditions have been reported [14]. This fact suggests that these rocks, together with the eclogites, formed part of a thick orogenic wedge [2]. Remnants of this orogenic wedge crop out as a continuous allochtonous unit (Cubito and Moura schists, in Spain and Portugal, respectively) located in the southern part of the Ossa-Morena Zone, north of the boundary marked by the Beja-Acebuches amphibolites. Thus, in the boundary between the Ossa-Morena and South Portuguese zones, a pile of rocks underwent HP–LT metamorphism during the Variscan orogeny, though, by contrast, the nearby Beja-Acebuches oceanic amphibolites underwent a LP–HT evolution [4,9,11].

Acknowledgements

The CICYT Spanish projects BTE2003-05128 and FEDER funds of the EU supported the field and laboratory research. We thank A. Tahiri and H. El Hadi for their help in the French version of the text. Three anonymous reviewers helped to improve the manuscript.

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier