Version française abrégée

Introduction

Une propriété marquante des réseaux de rivières est qu'ils présentent invariablement les mêmes lois d'organisation géométrique à toutes les échelles [4,27], indépendamment des contextes tectoniques et climatiques, ainsi que du cadre géologique en général. Cela semble en contradiction avec l'intuition selon laquelle les rivières, de par leur position à l'interface entre lithosphère et atmosphère, devraient au contraire être fortement influencées par les processus tectoniques et climatiques. En fait, malgré l'attention considérable qui a été portée à l'étude quantitative des réseaux hydrographiques (voir [27] pour une revue), il manque encore aujourd'hui une compréhension claire de ce qui lie la géométrie des réseaux hydrographiques aux mécanismes physiques responsables de leur développement [4,15,29]. Plus précisément, comment se fait-il que les réseaux hydrographiques puissent exister grâce à l'interaction entre tectonique et climat au sens large, d'une part, et en même temps présenter des propriétés géométriques essentiellement indépendantes de ces deux paramètres, d'autre part ?

La thèse que nous proposons dans cet article soutient que l'échec à comprendre le problème relevé ci-dessus provient essentiellement du fait que tous les modèles actuels de développement des réseaux hydrographiques, qu'ils soient conceptuels (voir [27]), analogiques [19,21,22,30,31] ou numériques [13,33,34,37,38], sont similairement inadéquats de par leur structure même, car ils n'envisagent toujours la croissance des réseaux qu'à l'intérieur de domaines aux bords fixes. Dans tous ces modèles, le réseau est donc contraint d'envahir la topographie soumise à l'érosion, essentiellement en partant des bordures et en se propageant vers l'intérieur (c'est-à-dire d'aval en amont, modèle headward growth de Howard [12]). Si une telle situation peut s'avérer adéquate pour la représentation de la croissance de réseaux à petite échelle, comme des incisions sur des versants, ou dans certains cas particuliers, comme le soulèvement en bloc d'un plateau (par exemple, le Colorado), nous suggérons qu'elle est en revanche inadaptée en général, dès lors que la topographie soumise à l'érosion s'étend horizontalement au cours du temps, comme dans le cas des chaînes de montagnes, qui s'élargissent au cours de leur évolution. Partant de cette constatation et en analysant ses implications, nous proposons dans cet article une nouvelle vision du développement des réseaux de drainage et des paramètres qui contrôlent leur géométrie.

Espacement régulier des rivières dans les orogènes linéaires

On peut voir, dans de nombreuses chaînes de montagnes relativement linéaires, que les rivières transverses (perpendiculaires à l'axe de l'orogène) sont espacées de manière remarquablement régulière. Hovius [10] a quantifié cette régularité et montré que le rapport de forme (R) entre la largeur de la chaîne (W, du front à la crête principale) et l'espacement des drains (S, mesuré au front de la chaîne) est toujours proche d'une valeur médiane

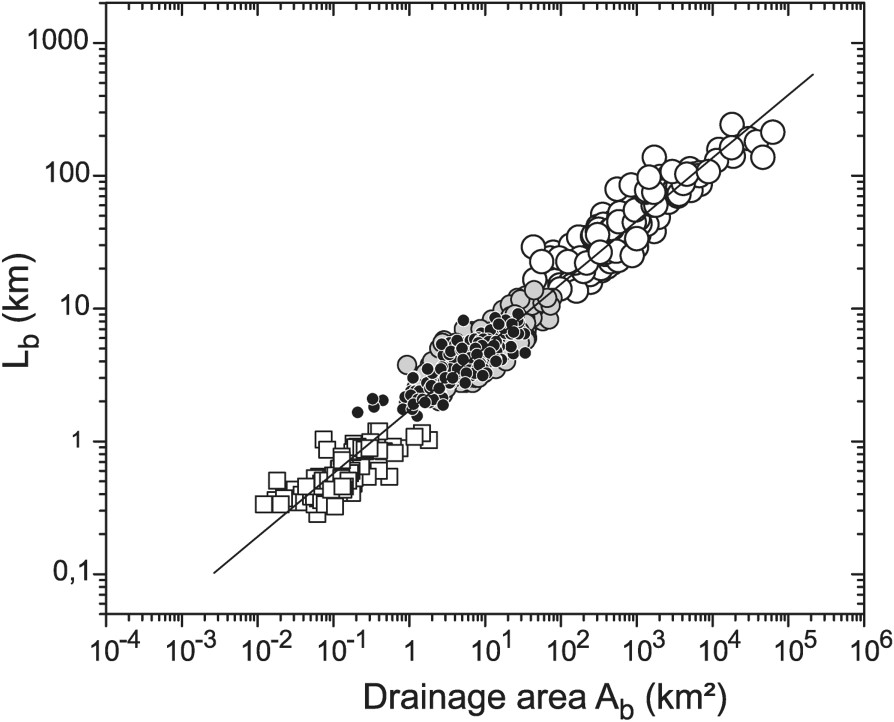

Recasting of mountain half-width (W) and river spacing (S) data into a log–log plot of basin length (

Recasting of mountain half-width (W) and river spacing (S) data into a log–log plot of basin length (

Réinterprétation des données de largeur de chaîne (W) et espacement des rivières (S) en termes de relation longueur (

Réinterprétation des données de largeur de chaîne (W) et espacement des rivières (S) en termes de relation longueur (

Croissance des réseaux dans un orogène en développement

Si nous supposons que la réorganisation des réseaux, en vue de maintenir un R proche de 2,1, n'est pas un processus dominant au cours de l'élargissement d'une chaîne de montagnes, il s'ensuit logiquement que la géométrie en plan des réseaux de drainage doit exister avant que ne commence l'érosion et ensuite être préservée. Nous proposons que la géométrie dendritique des réseaux de drainage résulte essentiellement de la coalescence des rivières à l'extérieur de la zone en érosion, dans les plaines (alluviales ou juste récemment émergées) situées au pied des chaînes de montagnes qui reçoivent les rivières venant de l'amont et où elles deviennent libres de divaguer latéralement et ainsi de se rejoindre. La géométrie dendritique ainsi acquise est ensuite « figée » (quenched ou trempée) dans la topographie, lorsque la chaîne s'élargit et absorbe les zones précédemment en sédimentation ou en transfert (Fig. 2). En coalesçant de cette manière, les rivières deviennent plus espacées les unes des autres, quand elles s'éloignent de la chaîne. Cette vision fournit donc un mécanisme simple par lequel une relation entre espacement des drains et distance à la source émerge naturellement. De plus, selon ce modèle, l'organisation géométrique des réseaux prend place à l'extérieur de la zone en érosion et est ainsi, de fait, essentiellement indépendante des conditions tectoniques et climatiques observées dans l'orogène.

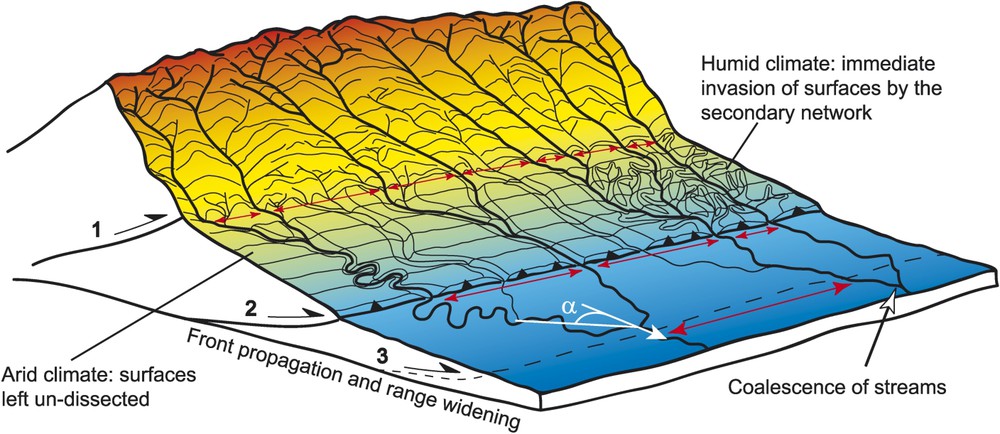

Conceptual sketch of drainage network development in widening topography. The rivers wander and coalesce on the lowland plains outside the range, increasing their spacing downstream (red arrows) at a rate that depends on the angle α (in plan view) with which streams flow with respect to the regional slope (white arrow). The resulting dendritic network gets ‘quenched’ in the landscape as the range front progressively propagates (steps 1, 2 and 3) and the foreland is uplifted. Depending on climate, a secondary network invades (right) or not (left) the surfaces between newly incised streams. If precipitation occurs later on the left part, the secondary network that will invade these surfaces will be more elongate because of the higher regional slope built during deformation. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.) Masquer

Conceptual sketch of drainage network development in widening topography. The rivers wander and coalesce on the lowland plains outside the range, increasing their spacing downstream (red arrows) at a rate that depends on the angle α (in plan view) ... Lire la suite

Schéma conceptuel de croissance des réseaux dans une chaîne de montagnes en développement. Les rivières qui sortent des reliefs viennent divaguer et se rejoindre sur la plaine à l'extérieur de la chaîne. Ce faisant, leur espacement augmente (flèches rouges), en fonction de l'angle moyen α (vue en plan) avec lequel elles s'écoulent par rapport à l'orientation de la pente régionale (flèche blanche). Le réseau dendritique ainsi formé est ensuite piégé dans le paysage en érosion, quand la chaîne s'élargit (étapes 1, 2, 3) et que les plaines d'avant-pays sont soulevées. En fonction du climat dans les zones nouvellement soulevées, un réseau secondaire peut s'établir (à droite) ou pas (à gauche) dans les surfaces entre les drains primaires. Dans la partie gauche où le climat est actuellement aride, les pentes peuvent être augmentées par la déformation, sans que l'incision secondaire ne se produise ; si le climat change ensuite, le réseau secondaire sur ces surfaces sera plus allongé (angles α faibles) que la normale. (Le lecteur est renvoyé à la version électronique de cet article pour l'interprétation des références à la couleur dans cette légende de figure.) Masquer

Schéma conceptuel de croissance des réseaux dans une chaîne de montagnes en développement. Les rivières qui sortent des reliefs viennent divaguer et se rejoindre sur la plaine à l'extérieur de la chaîne. Ce faisant, leur espacement augmente (flèches rouges), en ... Lire la suite

Contrôles sur la géométrie des réseaux

De nombreux modèles existent déjà, qui reproduisent la géométrie observée des réseaux de drainage [12,13,15,16,24,26,27,34,38]. Dans cette section, notre but est d'apporter un complément à ces modèles, en essayant de comprendre comment les rivières trouvent leur chemin sur une surface non incisée qui s'étend horizontalement au cours du temps et qui est progressivement absorbée par la croissance d'une chaîne de montagnes.

La distance à laquelle deux cours d'eau se rencontrent sur une surface inclinée est principalement dépendante de l'angle moyen selon lequel ces deux cours d'eau s'écoulent par rapport à la direction de la pente régionale. Nous suggérons que cet angle est contrôlé par le rapport entre la valeur de la pente régionale de la surface et sa rugosité. Une surface rugueuse peu inclinée verra probablement se développer des réseaux très arborescents pouvant former des angles forts avec la direction de la pente régionale, alors que des surfaces fortement inclinées auront plutôt des réseaux étirés ou même parallèles dans les cas extrêmes. Nous proposons une relation analytique simple qui lie l'angle moyen d'écoulement α au rapport Φ entre la pente locale

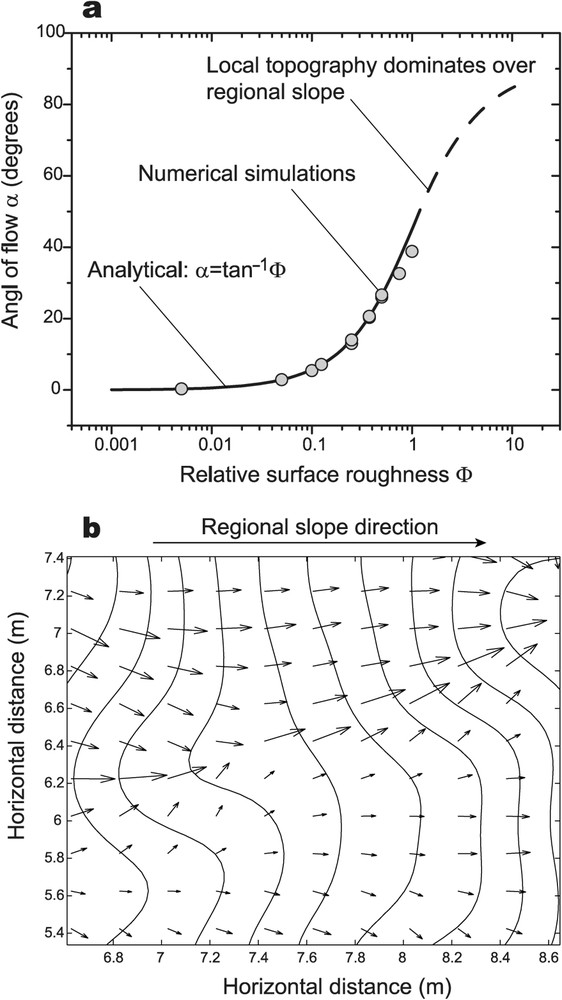

Influence of surface roughness on the orientation of water flow over random topography. (a) Angle of flow α (in plan view) with respect to the regional slope as a function of the relative surface roughness Φ (ratio between local slope, due to local roughness, and regional slope). Analytical predictions (solid curve) are confirmed by numerical simulations (grey circles) using the shallow-water equations to compute water flow over randomly perturbed, non-erodible, surfaces. (b) Detail of a numerical simulation of water flow on an inclined plane showing calculated water-flow velocity vectors and topographic contours. The grey circles on (a) represent mean flow orientations calculated for 11 surfaces with different roughness. Masquer

Influence of surface roughness on the orientation of water flow over random topography. (a) Angle of flow α (in plan view) with respect to the regional slope as a function of the relative surface roughness Φ (ratio between ... Lire la suite

Influence de la rugosité relative des surfaces sur l'orientation des écoulements. (a) Angle d'écoulement α (en plan) par rapport à l'orientation de la pente régionale, en fonction de la rugosité relative Φ (rapport entre la valeur de la pente locale, due à la rugosité, et la valeur de la pente régionale). Les prédictions analytiques (trait plein) sont confirmées par des simulations numériques (cercles gris) d'écoulement d'eau sur des plans inclinés rugueux simples et non érodables (équations d'écoulement en eau peu profonde). (b) Détail d'une simulation numérique montrant les vecteurs vitesse de l'écoulement et les contours topographiques. Les cercles gris sur (a) représentent la moyenne des orientations des écoulements pour 11 surfaces de rugosités relatives différentes. Masquer

Influence de la rugosité relative des surfaces sur l'orientation des écoulements. (a) Angle d'écoulement α (en plan) par rapport à l'orientation de la pente régionale, en fonction de la rugosité relative Φ (rapport entre la valeur de la ... Lire la suite

On peut montrer simplement que, dans un modèle géométrique simple de bassins de drainage rectangulaires, l'angle α contrôle la forme des bassins, donc le rapport R et le coefficient c dans la loi de Hack (Fig. 4a et b). Ainsi, la similarité de forme des bassins de drainage observée sous différents climats et dans différents contextes tectoniques, telle qu'elle est exprimée par les lois de Hack [4,6,18] et de Hovius [10], résulte donc de la croissance des réseaux par coalescence des rivières sur des surfaces ayant des propriétés géométriques similaires (pente régionale et rugosité) qui impliquent statistiquement des angles d'écoulement similaires. En effet, ces surfaces sont encore non incisées lorsque les rivières s'y rejoignent et ont donc par définition peu de chances de présenter (1) de forts contrastes de rugosité (surtout s'il s'agissait précédemment de surfaces de sédimentation), (2) de forts contrastes de pentes, car il est peu probable qu'une pente ait le temps de se développer avant que l'incision ne débute (et dès lors la surface n'est plus non incisée).

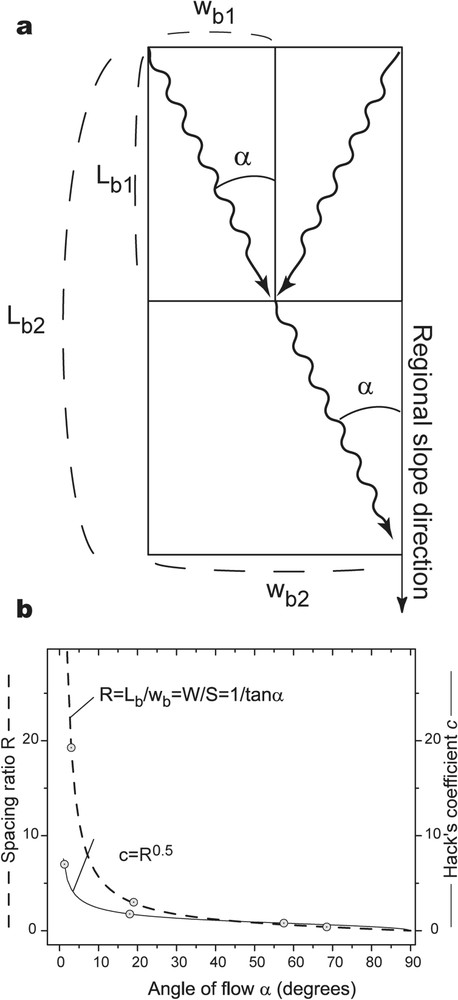

Geometric model of river coalescence and predicted basin shape parameters. (a) Plan view of rectangular basins defined by a master stream that deviates from the direction of the regional slope with an average angle α. This angle determines the shape of basins (e.g.,

Geometric model of river coalescence and predicted basin shape parameters. (a) Plan view of rectangular basins defined by a master stream that deviates from the direction of the regional slope with an average angle α. This angle determines the ... Lire la suite

Modèle géométrique de coalescence des rivières et prédiction des paramètres de forme des bassins. (a) Vue en plan de bassins rectangulaires définis par un drain principal qui dévie de l'orientation de la pente régionale avec un certain angle α. Cet angle détermine la forme des bassins (par exemple,

Modèle géométrique de coalescence des rivières et prédiction des paramètres de forme des bassins. (a) Vue en plan de bassins rectangulaires définis par un drain principal qui dévie de l'orientation de la pente régionale avec un certain angle α. ... Lire la suite

Cependant, les déviations à ces lois existent (par exemple, bassins trop étroits ou, au contraire, trop larges) et nous renseignent donc utilement sur des conditions spécifiques liées à la tectonique ou au climat, qui prévalaient lors de l'organisation du réseau avant qu'il ne soit figé dans la zone en érosion.

Conclusions et implications

Nous présentons un nouveau modèle conceptuel de développement des réseaux de drainage, basé sur deux points principaux : (1) les rivières coalescent à l'extérieur de la zone en érosion quand elles sont libres de divaguer latéralement, donnant naissance à un réseau dendritique non incisé, et (2) cette géométrie dendritique est ensuite piégée et figée dans le paysage quand la chaîne de montagnes s'élargit. Dans ce modèle, la géométrie du réseau reflète l'angle selon lequel se rejoignent les rivières et est donc fonction du rapport entre pente régionale et rugosité de la surface. Nous proposons que l'homogénéité de forme des bassins de drainage, exprimée par les lois de Hack et de Hovius, reflète la similarité des surfaces sur lesquelles s'organisent généralement les réseaux. Cette similarité des surfaces découle naturellement de leur nature non incisée. Dans le cadre de ce modèle, les rivières déviant par rapport aux lois normales deviennent ainsi des marqueurs fondamentaux des conditions spécifiques, en particulier tectoniques, qui prévalaient dans l'avant-pays des chaînes au cours de leur développement.

1 Introduction

Water flows over the Earth's surface and transports sediments from mountains to basins resulting in a dendritic network of river channels. Beyond the complex patterns they display in plan view, river networks are of fundamental interest, because they are a primary result of the interaction between tectonics, which raises the Earth's surface, and climate, which provides input of water [17,28]. Thus, river networks potentially bear signatures of the lithospheric and atmospheric processes that lead to their formation. However, paradoxically, one of the most striking properties of natural river networks is that they invariably follow the same geometric scaling rules [4,27]. These scaling laws are independent of geology, climate and tectonic setting. For example, Hack's law [6] relates the length (

2 Regular spacing of rivers in linear orogens

Many linear mountain belts display strikingly regular patterns of drainage transverse to their main structural trend. Hovius [10] quantitatively assessed this regularity by showing that the ratio (R) of mountain-belt width (W) to the mean spacing (S) of the main streams measured at the range front takes a median value of

By replacing the width of topography (W) with basin length (

We bring two arguments against this view. First, such reasoning neglects the considerable variation of basin shape observed in nature. Indeed, an analysis of all published individual spacing ratios [10,35] shows a distribution ranging from 0.4 to 19.3 around a mean of 3.0, with a standard deviation of 2.29. Thus, replacing this variability with a constant mean or median value places artificially unnecessary constraints on how one views the organisation of drainage networks in widening topography. Second, although processes such as sideward capture and divide collapse are occasionally observed in analogue experiments [8,21] and numerical simulations [23,33], evidence for their past occurrence in nature is rare [11]. It is thus doubted whether they are relevant for the organisation of river systems at large scales [35].

3 Network growth in a growing orogen

In this section, we propose a simple model aimed at explaining how drainage networks develop in growing orogens and how a relationship between spacing of rivers and distance to the main divide emerges.

Assuming that drainage reorganisation does not occur as a mountain belt widens, it follows that the observed planform structure of the drainage network has to be established in the landscape before erosion starts, and then preserved. How can this be? In many current and past mountainous settings worldwide, it is well known that when rivers flow out of uplifted relief, they enter a low slope area, where they lose their sediment transport capacity, deposit instead of erode, and become free to move laterally as alluvial rivers. Those rivers eventually coalesce as they flow on these undissected surfaces towards the sea, and thus become more widely spaced away from the relief (Fig. 2), giving rise to a dendritic geometry. However, it is also widely recognized that as the mountain front propagates and the range widens, alluvial foreland areas are progressively incorporated into the uplifted, erosional topography. The model proposed here consists in saying that the dendritic river network organised on the plain becomes incised and thus frozen or ‘quenched’ in the landscape (Fig. 2) when the orogen widens. The resulting ‘primary’ network is formed only by the downward continuation of streams coming from the erosion zone. Its organization is acquired on the lowland margins adjacent to uplifted topography and is progressively incorporated into the erosion zone as the mountain belt widens.

Uplift of the foreland can also lead to the development of a new ‘secondary’ drainage network within the undissected areas between primary channels (Fig. 2). The secondary network differs from the primary network in that it results from the initiation of new channels with channel heads contained entirely within the newly uplifted surface, rather than continuing existing channels sourced within previously uplifted topography. Thus, the secondary network is always of smaller scale than the primary network, which extends across the entire orogen.

We therefore envisage two main processes responsible for drainage development: the initiation of new channels and the downstream coalescence of existing channels. Although every drainage network ultimately begins with channel initiation, the actual drainage geometry is controlled largely by downstream ‘mouthward’ coalescence of existing channels on undissected surfaces. In the model proposed here, this downstream coalescence, which results from the natural aggregative behaviour of downhill fluid flow [29] is the main cause for dendritic drainage patterns. We emphasise that, except for pristine topography such as an emerging mountain belt, every surface newly submitted to erosion is adjacent to pre-existing topography, and thus receives, in addition to rainfall, an input of water in the form of streams entering at its upstream boundary.

The coalescence of streams in lowland areas and their progressive incorporation in the erosion zone as mountain ranges widen provides a simple mechanism to explain how a certain dependency between river spacing and mountain width (‘Hovius’ law') can be maintained during the enlargement of mountain ranges. This view of drainage development is consistent with a number of natural observations. First, in many active collision zones (e.g., Himalaya, central Apennines, Bolivian Andes), the large-scale drainage network is made-up of rivers that originate behind the highest peaks and flow transversely through the orogen and across the main structural trend. The simplest explanation for these observations is that these rivers are antecedent to deformation [20] and extended progressively downward as the mountain range widened, rather than cutting backward across the range (headward growth model). This is also true at smaller scales, when rivers are observed cutting across anticlines [32] for instance. Second, in some mountain belts (e.g., Pyrenees, European Alps) where alluvial bodies deposited in the now uplifted foreland are preserved, it has been shown [14,36] that the position of the rivers that were feeding these systems has not changed notably over significant time periods (107 yr). This clearly indicates that large modern rivers deeply incised into now uplifted forelands were once alluvial rivers depositing at the range front. Third, it is often observed that rivers cutting into bedrock at the front of orogens (e.g., Oregon Coast Range, Taiwan) have a meandering course similar to that of meandering alluvial channels. Although the possibility that bedrock meanders form in situ [1] cannot be excluded, a more simple explanation is to view them as inherited from an earlier alluvial stage, as is the case in our model.

4 Controls on network geometry

Many existing models produce dendritic river networks that satisfy the geometrical properties of natural drainage basins [12,13,15,16,24,26,27,34,38]. In this section, we intend to complement these models by investigating how streams find their path on an expanding surface and how the model we propose is quantitatively consistent with the observed drainage spacing relationships in mountain ranges.

The coalescence of streams on undissected surfaces requires that streams flow at a certain angle with respect to the direction of the regional slope. This angle dictates the rate at which streams merge in the downstream direction and therefore the dependency of river spacing on the distance to the main divide (range width). At first order, it can be intuitively suggested that this angle might be controlled by the geometry of the surface, and in particular, by both its slope and its roughness. This is consistent with observations that steep surfaces usually develop near-parallel drainage patterns (small angles of stream flow), whereas relatively flat surfaces present more branched river networks (higher flow angles). On a simple surface having a constant regional slope and a randomly distributed roughness described by a characteristic amplitude

| (1) |

In order to further investigate how the geometrical properties of the drainage network are related to the stream flow angle α (and therefore to the geometry of the surface via Φ), we consider a simple geometrical model of stream coalescence within rectangular basins (Fig. 4a). If the angle α with which streams flow is constant, basins grow self-similarly. As expected from a cursory dimensional analysis [6], this leads to a value of 0.5 for the exponent b in Hack's law following:

| (2) |

| (3) |

A value of

The angle with which streams flow in basins also determines the basin shape and thus both Hack's coefficient and the spacing ratio (Fig. 4b) following:

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

In a study of 38 of the world's largest basins [4], Hack's coefficient was reported to vary between

However, there are deviations to the average Hack's law and width-to-spacing relationships. Spacing ratios greater than 5 indicate unusually elongated basins formed on surfaces with a lower relative roughness (

Growing mountain ranges are not the only place where drainage networks develop and share the same geometric properties as the drainage networks discussed here. A well-known case is the case of plateau uplift in which a nearly flat or gently sloping surface is uplifted. In this case, the drainage geometry is set by the path followed by water as soon as water starts to flow on the surface and coalesce downstream. Thus the drainage geometry is also antecedent but, as noted above, contrary to growing mountain ranges, incision can only progress toward the inside of the surface, i.e. by ‘headward’ propagation. Thus, as for growing mountain ranges, we suggest that the drainage geometry in uplifted plateaus is strongly controlled by the geometry of the previously undissected surface, and the role of headward erosion is limited to the dissection in the landscape of already existing drainage paths, independently of tectonics and climate.

5 Conclusions and implications

In this work, we have presented a new conceptual model of river network evolution based on two main points. First, rivers typically coalesce on the lowland plains outside mountain belts, giving rise to an unincised alluvial dendritic river network. Second, mountain belts widen with time and, as they widen, uplift and incorporate the adjacent foreland, causing the pre-existing dendritic river network to incise and become quenched in the landscape. As a generalization of this view, we propose that the dendritic nature and geometric properties of drainage networks are antecedent to erosion and result largely from the downstream coalescence of upstream existing streams on yet undissected surfaces. This coalescence (and the drainage basin geometry) simply results from the fact that streams flow at an angle with respect to the regional slope, controlled by the geometrical properties of the surface. Because of its dependency on initial conditions and because it is ‘quenched’ in the landscape, the general planform geometry of drainage networks is relatively insensitive to vertical tectonic movements and climatic events subsequent to their formation. Instead, the geometry of drainage networks bears a unique picture of the Earth's surface at the time of river network formation and thus potentially carries signatures of the prevailing tectonic and climatic conditions. However it can also acts as a passive strain marker in regions that have undergone significant horizontal deformation [7].

This study brings a new perspective on how one views drainage development because we suggest that river network organisation occurs primarily (1) in a ‘mouthward’ way, i.e. from sources to the sea, instead of in a ‘headward’ way, as usually considered, (2) outside the uplifted topography where river networks are paradoxically now observed and most commonly studied, and (3) prior to erosion even though rivers may now be deeply incised in eroding landscapes.

The similarity of drainage networks expressed by Hack's law and the width-to-spacing relationship indicates that the undissected surfaces on which drainage develops generally have similar roughness (because they are undissected) and slopes (because drainage networks are quenched in the landscape before tectonics can significantly increase the slope). However, deviations from the normal values observed for Hack's law and spacing ratios potentially tell us about extreme or specific climatic and tectonic conditions. In particular, since the angle with which streams flow is related to the slope (and the roughness) of the Earth's surface at the time of drainage organisation, uncommon changes of stream orientation along their course in mountain ranges could reflect tectonically induced changes of the slope during the development of the orogen. In this view, the planform pattern of river networks and in particular the orientation of rivers with respect to the main regional slope can be viewed as a powerful geomorphic marker of the deformation in mountain ranges.

Future tests and applications of the model include, among others, (1) investigating growing drainage networks around the tips of actively growing anticlines and normal fault-blocks to see if the incipient geometry of these networks is maintained later in the uplifted zone, and (2) measuring average angles between rivers on recently dissected surfaces whose slope has not changed significantly since dissection and trying to connect river angles with initial slope and roughness, in order to later assess the initial slope of virtually any drainage network. Then, by comparing to the current slope of the studied drainage, it could then be possible to know if deformation has taken place, which is particularly interesting for situations where other information is lacking, such as drainage networks on Mars for example.

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and Philip Allen, ETH Zurich and ‘Université Pierre-et-Marie-Curie’ for funding this study.

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier