Version française abrégée

Le bassin des Flyschs maghrébins (BFM) représente un des domaines paléogéographiques majeurs de la chaîne Maghrébine. Les unités dérivées de la déformation du BFM sont interposées entre les unités du Domaine interne et celles du Domaine externe [5,15,18,34]. Des unités provenant du BFM sont pincées, même dans la pile de nappes de la cordillère Bétique. Elles affleurent amplement dans la partie occidentale de la chaîne, en particulier dans le Campo de Gibraltar [13–15], et elles se continuent en affleurements plus ou moins isolés jusqu’à la province de Murcie. Un bassin dont l’évolution tectono-sédimentaire est tout à fait semblable à celle du BFM a été reconnu dans l’Apennin méridional (océan Lucanien) et est considéré comme la continuation vers le nord-est du BFM [1,25].

Un substratum océanique, plus ou moins bien développé, est en général admis pour le BFM [4–6,12,21,25,26,32,34], tandis que sa position paléogéographique est encore discutée, parce que ce bassin a été considéré, quelquefois comme la seule continuation vers le sud-ouest de l’océan Liguro-Piémontais [5,12], d’autres fois comme une branche méridionale (océan Maghrébin) de la Téthys occidentale, tout à fait indépendante de sa branche septentrionale (Névadofilabride-Liguro-Piémontaise). Les deux branches seraient séparées par une microplaque mésoméditerranéenne, d’où seraient dérivées les unités internes des orogènes Bétique, Maghrébin et Apenninique [1,2,6,7,10,25,26].

Les successions déposées dans la partie interne (septentrionale) du BFM, dénommées Maurétaniennes [3], débutent avec des sédiments pélagiques siliceux et carbonatés du Jurassique supérieur–Crétacé inférieur et continuent au Crétacé–Paléogène, avec des dépôts pélagiques marneux et argileux à intercalations, plus ou moins fréquentes et épaisses, de turbidites gréseuses ou calcaires. Les successions stratigraphiques se terminent avec des formations turbiditiques silicoclastiques (flysch d’Algésiras en Espagne et flysch de Beni Ider au Maroc), qui témoignent de l’évolution comme avant-fosse du bassin Maurétanien, juste avant sa déformation et l’implication de ses terrains dans la pile de nappes en voie de mise en place. Par conséquent, l’âge de ces formations représente une contrainte fondamentale, qui ne peut pas être négligée dans les reconstructions de l’évolution géodynamique de la chaîne Maghrébine et de la cordillère Bétique.

Récemment, dans le secteur sicilien de la chaîne Maghrébine il a été possible de bien définir l’âge de déformation des nappes issues du Domaine interne, empilées au cours de l’Aquitanien [2,9,20], et des nappes du BFM, qui se sont mises en place entre le Burdigalien (les nappes Maurétaniennes [11]) et le Langhien (les nappes les plus externes [29]). Ces âges sont identiques aux âges reconnus dans l’Apennin méridional pour les unités de l’océan Lucanien [17].

Dans l’arc de Gibraltar, des structures très semblables ont été reconnues du côté Rifain et du côté Bétique [15], mais l’âge des sédiments maurétaniens d’avant-fosse est encore discuté, des âges compris entre l’Éocène supérieur et le Miocène inférieur ayant été admis pour les flyschs d’Algésiras et de Beni Ider [6,7,20,27]. En particulier, les âges burdigaliens [8,19,24], proposés pour les niveaux les plus élevés des flyschs d’Algésiras et de Beni Ider ont été remis en cause ou non considérés. Nous avons donc échantillonné des coupes significatives du flysch d’Algésiras (Punta Carnero, Tarifa et Arroyo del Guadalmedina dans le Campo de Gibraltar ; Cortijo de Bacia Cámara dans le Corredor de Colmenar) et du flysch de Beni Ider (Esperada, Beni Harchane et Oued el Kebir aux environs de Tétouan ; Dchar Foual près de Ksar-es-Sghir), dans lesquelles le sommet et la base des formations sont bien exposés. Nous avons échantillonné même les niveaux les plus élevés de la formation stratigraphiquement située immédiatement au-dessous des flyschs d’Algésiras et de Beni Ider (formation Colorín [30]), représentée par des argiles et siltites rouges et vertes. Dans tous ces échantillons, on a concentré et analysé le nannoplancton calcaire, qui s’est révélé très utile dans l’étude des formations turbiditiques où les fossiles sont très rares et le remaniement systématique.

Dans les niveaux sommitaux de la formation Colorín, on a reconnu des taxa qui indiquent un âge tantôt Chattien, tantôt Aquitanien. L’âge qu’on a reconnu à la base du flysch de Beni Ider n’est pas plus ancien que le Chattien dans toutes les coupes étudiées, tandis que la base du flysch d’Algésiras a livré, dans certaines coupes, des taxa connus à partir du Chattien et, dans d’autres coupes, des taxa connus à partir du Miocène inférieur. Au sommet des formations des flyschs d’Algésiras et de Beni Ider, au contraire, on a reconnu partout des taxa signalés à partir du Burdigalien supérieur (Discoaster exilis, D. musicus, D. variabilis, Sphenolithus heteromorphus).

Par conséquent, l’évolution en avant-fosse du sous-domaine Maurétanien du MFB ne débute pas avant l’Oligocène supérieur. La déformation de ce sous-domaine et la structuration du prisme d’accrétion océanique n’ont pas eu lieu avant le Burdigalien supérieur, étant donné que les niveaux les plus élevés des flyschs d’Algésiras et de Beni Ider se sont avérés être d’âge Burdigalien supérieur. En outre, les âges reconnus s’intègrent bien dans un contexte régional étendu aux unités du domaine interne Bético-Rifain, du fait que les flyschs d’Algésiras et de Beni Ider ont le même âge que les dépôts syn- et tardi-orogéniques des unités Malaguides et Ghomarides, ainsi que de la dorsale calcaire Rifaine [30,35], et, enfin, du groupe de Viñuela-Sidi Abdeslam, qui scelle les contacts entre toutes les unités du Domaine interne [22,30]. De plus, ces âges s’accordent très bien aussi avec les âges reconnus dans le secteur sicilien de la chaîne Maghrébine et dans l’Apennin méridional [11,16,17], où le début de la sédimentation silicoclastique dans les unités maurétaniennes, ou de type maurétanien, est d’âge Burdigalien inférieur et les niveaux les plus élevés sont d’âge Burdigalien supérieur.

Les âges reconnus, enfin, permettent d’exclure une collision continentale d’âge Éocène entre les unités internes, déjà empilées et liées à la plaque Ibérique, et la marge Africaine. La collision n’a eu lieu qu’au Miocène moyen, en accord avec beaucoup d’auteurs [11,18,23,25,26,31,33,35]. La collision est donc contemporaine le long de toute la chaîne Maghrébine, du Rif à la Sicile orientale, et tout diachronisme dans sa structuration, autrefois plus d’une fois proposé [12,28], ne peut pas être accepté, étant en opposition avec des données stratigraphiques qui ne peuvent pas être négligées.

1 Introduction

The Maghrebian Flysch Basin (MFB) represents a major palaeogeographic domain involved in the building of the Maghrebian Chain [5,15,18,34], and its terrains widely crop out from the Rif to the eastern Sicily. Terrains deposited in the MFB are also present in the nappe pile of the Betic Cordillera, in particular in the Campo de Gibraltar [13–15]; eastward, they have been recognized in some outcrops scattered along the contact between the Internal and External Zones, from the Corredor de Colmenar, north of Malaga, up to the Vélez Rubio area, in the Murcia Province [30].

Recently, terrains showing a tectono-sedimentary evolution quite similar to that of the MFB have been identified in the southern Apennines [1,25] and, at present hypothetically, also in the northern Apennines [10]. These terrains have been interpreted as deposited in an oceanic belt (Lucanian Ocean) representing the extension towards the northeast of the MFB [1,25].

The MFB has been considered as the sole extension toward the west of the Piedmont-Ligurian Oceanic belt [12,5] or as a southern branch of the western Tethys, separated by means of a Mesomediterranean microplate from a Nevadofilabride–Piedmont branch [1,2,6,7,10,25,26,30]. The oceanic nature of the MFB has been debated, because outcrops of a magmatic substratum are very few along the chain from the Rif to the Sicily [4,21,32] and are completely lacking in the Betic Cordillera: therefore the occurrence of a thinned, only locally oceanized, continental substratum has been also suggested. The oceanic substratum, on the contrary, is well recognizable in the Lucanian Ocean units of the southern Apennines, where basic and ultrabasic rocks are widely exposed [1].

The sedimentary successions deposited on the internal (northern) and external (southern) sides of the MFB show a different development. The internal successions, the only considered in the present study, are known as Mauretanian successions [3]. They start with Upper Jurassic–Lower Cretaceous pelagic and turbiditic sediments and they develop in the Cretaceous–Palaeogene with marly-clayey pelagic deposits, alternating with siliciclastic and carbonate turbidites. The successions end with thick siliciclastic, and locally volcaniclastic, sandy-clayey turbiditic formations, testifying to the evolution to a foredeep of the Mauretanian sub-domain, immediately before its deformation (Flysch, sensu [25]). Therefore, these latter formations represent a basic constraint to define the age of the onset of the compressive deformation in the MFB and that of the stacking of the nappes originated from the MFB.

Recently, in the Sicilian sector of the Maghrebian Chain, some studies have well defined the age of the flysch formations, both of the Internal and MFB Units, as well as the age of the clastic formations unconformable on all these units. Therefore, the deformation timing of both domains is well constrained: the Internal Units are stacked in the Aquitanian [2,9,20], whereas in the MFB Domain the flysch sedimentation starts in the Burdigalian in the Mauretanian Units [11], and in the Langhian in the external ones [29]. Similarly, the age of the formations unconformably lying above all these units resulted to be diachronous: Late Burdigalian, Middle Langhian, and Serravallian ages characterize the base of the successions resting unconformably on the Internal Domain, the Mauretanian and the External MFB Units, respectively [2,11]. These ages are quite similar to those recognized in the southern Apennines [17 and references therein].

In the Gibraltar Arc, characterized by a similar structure on both the Rifian and Betic sides [15], the age of the Mauretanian foredeep sediments, represented by the Beni Ider and Algeciras Fms, is still debated. In some papers, these deposits have been essentially considered as Late Eocene–Oligocene in age [6,7,20,27], and only the uppermost levels have been attributed to the Aquitanian. Burdigalian ages [8,19,24] have been questioned [27] or not taken into account [6,7]. Besides, the stratigraphic constraints to the closing age of the MFB, and the subsequent continental collision, have been fully neglected in some geodynamic models, in which the collision in the Gibraltar Arc is considered as Late Eocene in age [28].

In this paper, we report on the results of a re-examination of the age of the Beni Ider and Algeciras Fms. We have sampled some well-exposed sections and analyzed the calcareous nannofossils, because, in our experience, these fossils provide the best stratigraphic results for dating turbiditic successions, where fossils are very scarce and their reworking systematic.

2 The stratigraphic succession of the Mauretanian units

The Mauretanian successions start with ophiolitic cover sediments (Upper Jurassic–Lower Cretaceous radiolarites, siliceous claystones, cherty limestones) [4,32], passing to Valanginian pelagic marls and variegated clays alternating with turbiditic deposits, represented by allodapic limestones and fine-grained quartzarenites. These latter can be more than 700 m thick in the Barremian–Albian (Jebel Tisirène section). In the Late Cretaceous, the calcareous turbidites clearly prevail on the siliciclastic ones. As from the Maastrichtian, the sedimentation begins to be mainly pelagic and it is represented by variegated marls and clays with beds of allodapic limestones, calcarenites and microcodium-bearing limestones of Palaeocene up to Eocene age [15,16,20]. These sediments are substituted by a calcareous turbidite formation, consisting of grey calcarenites and violet mudrocks with some beds of calcareous microbreccias, sometimes rich in nummulites. This formation, formerly considered as being of Eocene age, actually resulted as an Oligocene key-level at the scale of the MFB, which has been related to the sea-level fall characterizing this epoch [16]. A sudden return to varicoloured silty and muddy sediments testifies to the end of the turbiditic event and it precedes the foredeep stage, characterized by thick successions of sandy-clayey turbidites.

3 The Betic Algeciras Nappe

In the Betic Cordillera, the Mauretanian Units are represented by the Los Nogales Nappe [13], consisting only of Lower Cretaceous rocks, and – tectonically below that one – by the Algeciras Nappe, made up of Upper Cretaceous–Lower Miocene formations.

The upper formation of the Algeciras Nappe [13] consists of sandy-clayey turbidites (Flysch of Algeciras), which form a coarsening and thickening upward succession, more than 1000 m thick. The Algeciras Flysch grades downwards into varicoloured, prevailingly reddish, mudrocks and siltites, with a few thin beds of calcareous and siliciclastic turbidites, of the Colorín Fm [30]. The passage is frequently marked by greyish mudrocks, some tens of metres thick. The upper part of the Colorín Fm. has been attributed to the Oligocene owing to the presence of Lepidocyclina-rich beds [13], but Upper Oligocene–Lower Miocene nannofossils have been recently recognized [16]. However, an Aquitanian age was demonstrated, using planktonic foraminifera, for the uppermost levels in some outcrops of the Corredor de Colmenar [30]. As regards the age of the Algeciras Flysch, the base of the formation has been considered as Late Oligocene [13] or Early Miocene in age [14]; many authors recognized Aquitanian and Lower Burdigalian levels in the Algeciras Flysch [24,30]. Finally, diachronism for the age of the base of the Algeciras Flysch from the Late Oligocene to the Early Miocene has been suggested [30].

The Colorín and Algeciras Flysch Fms have been sampled in some sections already known in the literature and along a recent road-cut near Tarifa.

3.1 Punta Carnero section

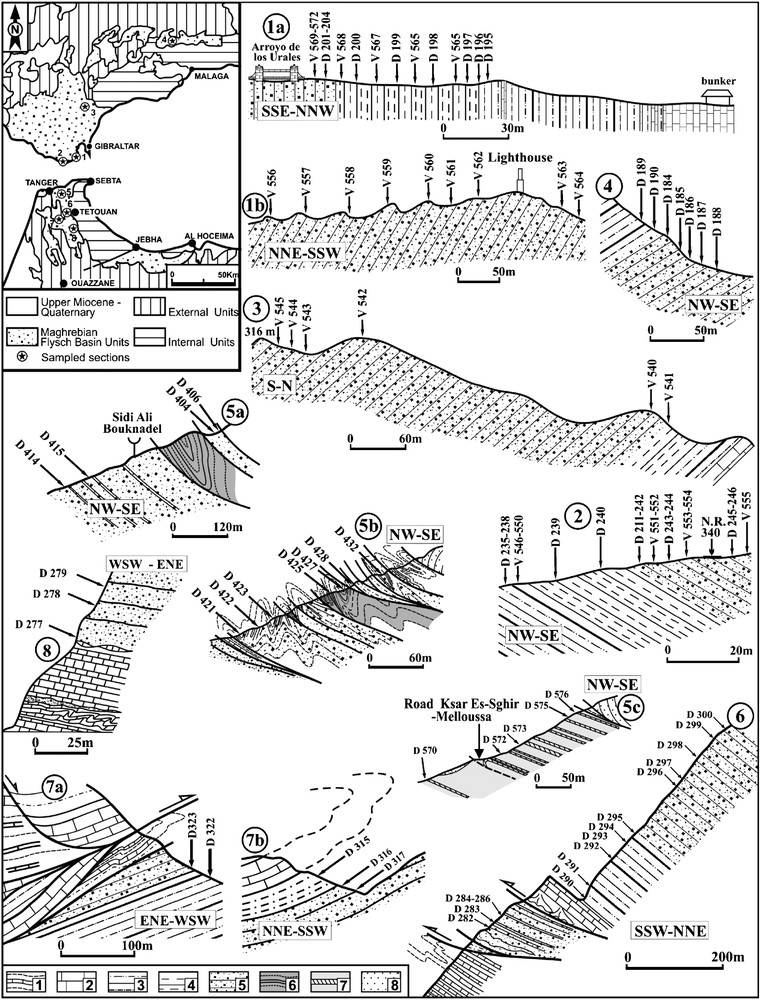

The section is exposed along the coast south of Algeciras (Fig. 1) between the Punta de Getares and the lighthouse of Punta Carnero [13,27]. It starts on the shore where an old bunker is placed on the Oligocene calcareous turbidites, which grade into the reddish and green siltites of the base of the Colorín Fm. The passage between this latter and the Algeciras Flysch is marked by a near 60-m-thick interval of mainly greyish mudrocks with interposed thin sandstone beds, followed by arenaceous turbidites, generally characterized by thick beds with thin muddy interval (Fig. 1, section 1a). The succession continues for several hundreds of metres. The upper sampled levels crop out near the lighthouse of Punta Carnero, between the Cala de la Canonera and the Cala de la Parra (Fig. 1b). In this section, the uppermost levels of the Colorín Fm., the greyish mudrocks, and the basal and upper beds of the Algeciras Flysch have been sampled. The location of the samples is reported in Fig. 1, sections 1a and 1b.

(A) Sketch map of the Gibraltar Arc and location of the studied sections. (B) Sections, with location of the fossil-bearing samples: (1a and 1b = Punta Carnero; 2 = Tarifa; 3 = Arroyo del Guadalmedina; 4 = Cortijo de Bacia Cámara; 5a, 5b, and 5c = Dchar Foual, 6 = Esperada; 7a and 7b = Beni Harchane; 8 = Oued El Kebir). Legend of the sections: 1, Cretaceous–Eocene sediments of the Algeciras and Beni Ider Nappes; 2, Oligocene calcareous turbidites of the Algeciras and Beni Ider Nappes; 3, siltstones and mudrocks of the Colorín Fm.; 4, greyish marls at the base of the Algeciras Flysch Fm. and locally also at the base of the Beni Ider Flysch Fm.; 5, sandy and sandy-pelitic turbidites of the Algeciras and Beni Ider Flysch Fms; 6, brown tobacco marls in the upper part of the Beni Ider Flysch Fm.; 7, marls with silexites of the upper part of the Beni Ider Flysch Fm.; 8, Cretaceous sediments of the Tisirène Nappe.

Fig. 1. (A) Carte schématique de l’arc de Gibraltar et localisation des coupes étudiées. (B) Coupes et position des échantillons significatifs (1a et 1b = Punta Carnero ; 2 = Tarifa ; 3 = Arroyo del Guadalmedina ; 4 = Cortijo de Bacia Cámara; 5a, 5b et 5c = Dchar Foual, 6 = Esperada; 7a et 7b = Beni Harchane; 8 = Oued El Kebir). Légende des coupes : 1, sédiments du Crétacé–Éocène des nappes d’Algeciras et de Beni Ider ; 2, turbidites calcaires de l’Oligocène des nappes d’Algésiras et de Beni Ider ; 3, siltites et pélites de la formation de Colorín ; 4, marnes grisâtres à la base de la formation du flysch d’Algésiras et, localement, même à la base de la formation du flysch de Beni Ider ; 5, turbidites gréseuses et gréso-pélitiques des formations du flysch d’Algésiras et de Beni Ider ; 6, marnes marron-tabac de la partie supérieure de la formation du flysch de Beni Ider ; 7, marnes et siléxites de la partie supérieure de la formation du flysch de Beni Ider ; 8, sédiments crétacés de la nappe de Tisirène.

3.2 Tarifa section

The section is located near Tarifa along the new road-cut at 84.5 km of the N.R. 340, northwest of the crossroad for the city (Fig. 1, section 2). The Colorín Fm. is well exposed over a thickness of 50–60 m and grades into the Algeciras Flysch by means of a 20-m-thick layer of greyish mudrocks, in which a few thin sandstone beds are intercalated. The Algeciras Flysch shows up to 50-cm-thick beds.

3.3 Arroyo del Guadalmedina section

The section [13,27] is located 9 km northeast of Jimena de la Frontera, on the western side of the Arroyo del Guadalmedina, between Haza de la Encina and Cortijo Los Marinos. The Algeciras Nappe succession is exposed from the Upper Cretaceous–Palaeogene beds up to the Algeciras Flysch, the latter cropping out for a thickness of at least 500 m. In this section, the basal and upper levels of the Algeciras Flysch have been sampled (Fig. 1, section 3).

3.4 Cortijo de Bacia Cámara section

The section is located in the Corredor de Colmenar, 10 km south of Antequera, along a small valley located 500 m to the east of the Cortijo de Bacia Cámara. The succession is overturned and the passage from varicoloured siltites and mudrocks of the Colorín Fm. to thin- and medium-bedded sandy-clayey turbidites of the Algeciras Flysch is well exposed (Fig. 1, section 4).

3.5 Biostratigraphic data

The biostratigraphic study has been carried out using calcareous nannofossils. Taking into account the extensive reworking and the poor fossil assemblages, the analyses have been based only on the first occurrence of species, allowing ages to be determined as ‘not older than...’ Samples have been prepared following a practice involving crushing and treatment with sodium hypochlorite 10% during 6 h and centrifuging with spin at 2500 rpm.

The recognized assemblages are usually poor and characterized by a few species in which clearly reworked Cretaceous–Eocene taxa prevail. Taxa firstly occurring during the Palaeogene and present up to the Middle Miocene (Coccolithus pelagicus, Discoaster deflandrei, Helicosphaera euphratis, H. intermedia, H. obliqua, Sphenolithus moriformis, etc.), therefore compatible with Upper Oligocene–Lower Miocene markers, are frequent.

As regards the varicoloured mudrocks forming the upper part of the Colorín Fm. in the Punta Carnero and Tarifa sections, the occurrence of S. ciperoensis and H. recta testifies to an age not older than Late Oligocene (Zone NP25 = Zone CP19b), while in the Cortijo de Bacia Cámara section H. carteri indicates an age not older than Aquitanian (NN1 = CN1a).

The basal levels of the Algeciras Flysch resulted to be not older than Late Oligocene in the Punta Carnero and Arroyo del Guadalmedina sections (H. recta and S. ciperoensis), whereas in the Tarifa and Cortijo de Bacia Cámara sections they must be attributed to the Burdigalian (NN2 = CN1c), due to the occurrence of Orthorhabdus serratus, H. mediterranea, H. ampliaperta, and D. druggii.

The upper levels of the Algeciras Flysch, sampled in the Punta Carnero section, resulted to be not older than Aquitanian (NN1 = CN1a; occurrence of H. carteri), whereas in the Arroyo del Guadalmedina section S. heteromorphus testifies to the presence of layers not older than Late Burdigalian (NN4 = CN3).

4 The Rifian Beni Ider Nappe

In the Rifian Maghrebides, the Mauretanian Sub-Domain is represented by the Tisirène and Beni Ider Nappes, whose terrains formed a common stratigraphic succession before their dismemberment and overthrusting during the Alpine tectonics [15,35].

The Beni Ider Nappe, defined near the locality of Tlata of Beni Ider, is mainly constituted by the sandy-clayey turbidites of the Beni Ider Flysch Fm., following Upper Cretaceous–Palaeogene varicoloured mudrocks and calcareous turbidites.

The stratigraphic succession is quite similar to that of the Algeciras Nappe and the terrains immediately underlying the Beni Ider Flysch are represented by varicoloured mudrocks and siltites similar to those of the Betic Colorín Fm.

The Beni Ider Flysch consists of an alternation of sandy-clayey and sandy-marly turbidites, frequently reaching a thickness of 1800 m, with a maximum of 2150 m. Beds of coarse conglomerates, supplied by the erosion of the Internal Domain, have been recognized in its lower part [35].

As regards the age of the Beni Ider Flysch, Upper Aquitanian–Burdigalian microfaunas were recognized in levels whose exact position in the succession was not known [8]. Ages comprised between the Chattian and the Early Burdigalian have been suggested in the Ksar-es-Sghir area [19]. An Early Burdigalian age for the youngest strata, made up of marls and silexites, was also reported [19,35]. On the contrary, other authors [6,7,27] suggest a Late Eocene–Oligocene age: only the uppermost levels of the Beni Ider Fm. should reach the Aquitanian.

We re-examined and sampled some selected sections near Tétouan, where the transition from the mudrocks of the Colorín-like Fm. to the Beni Ider Flysch is well exposed. The highest levels of the Beni Ider Flysch have been sampled in the area of Ksar-es-Sghir.

4.1 Dchar Foual area sections

In the Dchar Foual area, the Beni Ider Nappe widely crops out under the quartzarenites of the Tisirène Nappe, in a complex tectonic setting, characterized by numerous slices, showing overturned and isoclinal folds (Fig. 1, sections 5a–c). The successions, from the base to the top, are constituted as follows:

- (a) the lowest layers consist of calcareous turbidites with thin intervals of grey–green mudrocks, or of red and green Colorín-like clays and siltstones, both at the footwall of the thrust leading the Beni Ider Flysch to directly override above them. The sample DS 428 has been collected in the Colorín-like mudrocks;

- (b) the lower–middle part of the Beni Ider Flysch is represented by 500–600-m-thick mica-rich quartzo-feldspatic litharenites with grey–green marly levels. The samples DS 398–399 and DS 421–424 have been collected in the basal part of the interval; sample DS 400–417 is in the middle–upper part;

- (c) the upper part of the succession is characterized by about 200 m of prevailing green-light and brown-tobacco marls, alternating with thick-bedded amalgamated sandstones and with decimetre-sized (30–90 cm thick) fine-grained volcaniclastic siliceous levels (silexites). Samples DS 419 and DS 425–427 have been collected in this interval;

- (d) the uppermost part of the succession, about 150 m thick, consists of alternating of decimetre-sized levels of silexites and light greenish marls, in which the samples DS 396–397 and DS 570–576 have been collected.

4.2 Esperada section

The section is located near the Esperada locality to the northern side of Tangier–Tétouan road (X: 487.75; Y: 550.00), and displays a duplex structure with two slices (Fig. 1, section 6). The lower slice crops out on the northern bank of the Oued Sperada up to an abandoned quarry, where calcareous turbidites mark the base of the upper slice (Fig. 1, section 5).

In the lower slice, siltites and siliciclastic turbidites of the Beni Ider Flysch occur. All these formations are strongly deformed and sheared; so the whole succession is not thicker than 200 m. At 40 m from the top of such slice, the Beni Ider Flysch displays some centimetre-thick silexite layers difficult to individualize [35], which are generally considered as representative of the higher part of the formation and as Early Burdigalian in age [20].

In the upper slice, the calcareous turbidites are followed by 30-m-thick variegated mudrocks and siltstones associated with thin-bedded and very fine-grained sandstones, quite similar to the Colorín-like Fm. These rocks are progressively replaced by grey and brown mudrocks and marls in which some siliciclastic turbidites are intercalated, that quickly become more frequent upwards. Here the Beni Ider Flysch shows distal features, testified to by the great abundance of muddy and marly intervals.

4.3 Beni Harchane section

The Beni Harchane (Beni Harfa Auct.) section is approximately located 1 km southeast of the Beni Harchane village (X: 478.45; Y: 546.1), 25 km west of Tétouan, starting from an open quarry for the extraction of calcarenites.

On the wall of the quarry, a very complex westward-directed duplex structure is exposed (Fig. 1, section 7a). The succession of the lower slice is represented by variegated marls and siltstones, with thin beds of limestones or fine-grained sandstones, similar to those of the Betic Colorín Fm., grading into mica-rich marly-arenaceous turbidites associated with rare calcareous turbidites, which represent the basal part of the Beni Ider Flysch (Fig. 1, section 7a). In the second slice, only terrains lower than those of the Colorín-like Fm. crop out. Above the crest of the quarry wall, the succession is covered for some metres, and subsequently overturned variegated mudrocks of the Colorín-like Fm., passing to marly–arenaceous lithofacies of the Beni Ider Flysch, are exposed (Fig. 1, section 7b).

4.4 Oued El Kebir section

This section is located about 1250 m WNW from the crossroad for Moulay Abdessalam and Beni Ider (X: 498.25; Y: 540.9) of the National Road Tétouan–Al Hoceima. The section is well exposed in the flank of a meander of Oued El Kebir, which has eroded the slope to form a cliff where an almost 60–70-m-thick succession crops out (Fig. 1, section 8).

At the base of the section, thick-bedded calcareous turbidite strata, with thin layers of grey mudrocks, becoming exclusively red and green upward, are observable. These strata pass to siliciclastic turbidites of the Beni Ider Flysch, without any interposition of variegated mudrocks and siltstones. The passage, however, is marked by a grey–yellowish marly interval, up to 5 m thick. In this section, the Beni Ider Flysch is characterized by alternating grey mudrocks and sandstones. The arenite beds rapidly become very abundant, reaching 30–40 cm in thickness.

4.5 Biostratigraphic data

The general features of the nannofossil associations recognized in the highest formations of the Beni Ider Nappe are quite similar to those of the Betic Algeciras Nappe.

As regards the Colorín-like varicoloured siltstones and clays, most of the samples were barren, but in the whole sampled section, taxa (S. ciperoensis, H. recta) firstly occurring in the Zone NP25 = Zone CP19b (Chattian) have been recognized.

Moreover, the basal levels of the Beni Ider Flysch testify to an age not older than Chattian (H. recta, S. ciperoensis, Triquetrorhabdulus carinatus). In higher levels, Aquitanian (H. carteri and S. delphix; NN1 = CN1) and Early Burdigalian (H. mediterranea and S. belemnos; top NN2 = CN2) ages have been recognized. In the uppermost marly and silexitic levels of the Dchar Foual sections, D. exilis, D. musicus, and D. variabilis, indicating an age not older than Late Burdigalian (NN4 = CN3), have been recognized, whereas only S. belemnos (top NN2 = CN2; Early Burdigalian) has been found in the silexites of the Esperada section.

5 Discussion and conclusions

The varicoloured siltstones and mudrocks of the Betic Colorín Fm. and the equivalent Rifian rocks have generally furnished nannofossils assemblages characterized by markers indicating an age not older than Late Oligocene (Zone NP25 = Zone CP19b). However, in the Cortijo de Bacia Cámara section, in agreement with what already evidenced by [30], markers indicating an age not older than Aquitanian (Zone NN2 = Zone CN1c) have been recognized.

Similarly, as regards the age of the basal levels of the Algeciras Flysch, one can outline that they resulted to be not older than Late Oligocene in the Punta Carnero and Arroyo del Guadalmedina sections and not older than Burdigalian in the other sections. The uppermost levels of the same formation resulted to be not older than Late Burdigalian (Zone NN4 = Zone CN3) in the Arroyo de Guadalmedina section, whereas in the upper levels of Punta Carnero section, only taxa firstly occurring in the Aquitanian (Zone NN1 = CN1a Zone) have been recognized.

In the Rif, nannofossil assemblages of the basal levels of the Beni Ider Flysch indicate an age not older than Late Oligocene in all the studied sections. Markers testifying to ages not older than Aquitanian and Early Burdigalian have been identified in stratigraphically higher levels, whereas in the Dchar Foual sections the uppermost levels of the formation, characterized by abundant silexite beds, are not older than Late Burdigalian (Zone NN4 = Zone CN3).

Therefore, no reasonable doubt seems to exist about the Late Burdigalian age of the uppermost levels of the Algeciras and Beni Ider Flysches, and about the Late Burdigalian age of the main deformative phase in the Mauretanian Zone of the MFB in the Gibraltar Arc. As regards the age of the onset of the foredeep sedimentation in the Betic-Rifian MFB, it can be still debated, because biostratigraphic data testify to both Late Oligocene and Early Miocene ages for the siliciclastic supply. This fact can be attributed to an inadequacy of the biostratigraphic data or to uneven and erratic development of the turbidite fans in the basin rather than to a true diachronism. However, it is impossible to admit foredeep sedimentation older than Late Oligocene, because in all the sections of the Algeciras and Beni Ider Flysch, and in the underlying Colorín Fm. also, samples furnished taxa whose first appearance is not older than Late Oligocene. Besides, the above-reported ages fit well in a regional context considering also the Betic-Rifian Internal Domains. In fact, these ages are coeval with those of syn- and late-orogenic deposits characterizing the units that originated from the Internal Domain, as the Malaguide, Ghomaride, and Rifian Dorsale Calcaire Units [30,35], and, finally, the Viñuela-Sidi Abdeslam Group, the latter unconformably lying on the above internal units [22,30].

A comparison with the available data in the Sicilian Maghrebides and in the southern Apennines [11,16,17] is very interesting. In such orogenic sectors, the onset of the siliciclastic sedimentation in the Mauretanian or Mauretanian-like units is Burdigalian in age (occurrence of S. belemnos), while the upper levels reach the Late Burdigalian (occurrence of Calcidiscus leptoporus, C. macintyrei, and D. variabilis). Therefore, it must be outlined that the foredeep stage and the deformation of the Mauretanian Sub-Domain are coeval in the Betic Cordillera, all along the Maghrebian Chain, from the Rif to the Sicily, and also in its continuation in the southern Apennines (Lucanian Ocean).

In conclusion, the Mauretanian silisiclastic turbiditic foredeep sedimentation did not start earlier than the Late Oligocene and reached the Late Burdigalian; it was fed by the Internal Units, which were already stacked and affected by fast uplift and strong erosion. The Algeciras and Beni Ider Flyschs predate the beginning of the compressive deformation in the MFB, and consequently, all reconstructions of the tectonic evolution of the Gibraltar Arc, suggesting a deformation of the MFB and a collision between the Betic-Rifian Internal Units, docked to the Iberian Plate, and the African margin earlier than the Middle Miocene [12,28], cannot be shared, because basic stratigraphic constraints are not considered. The data reported in this study support a continental collision coeval all along the Maghrebian Chain, from the Gibraltar Arc to the eastern Sicily [11], and a Middle Miocene accretion of the Mesomediterranean microplate against the North African margin [11,23,25,26,33,35].