1 Introduction

Oligotrophic high mountain lakes, which are scarce in the Mediterranean area, represent ideal ecosystems in which to study sediment-water interaction as a consequence of the low-nutrient content in the water column. Several mechanisms have been suggested to control the exchange of nutrients, mainly phosphorus (P), across the sediment-water interface (Boström, 1982; Boström et al., 1988; Forsberg, 1989; Golterman, 2004). Whereas in eutrophic lakes, chemical mechanisms mediated by redox conditions are likely to strongly influence the soluble reactive phosphorus (SRP) exchange across the sediment-water interface, in oligotrophic lakes physical processes can be particularly noteworthy.

In fact, resuspension may play a key role in the nutrient dynamics of shallow lakes, where sediment often undergoes continuous wave action. Several consequences could arise from sediment resuspension:

- • increased turbidity may reduce light penetration which can diminish primary production and ultimately promote biological changes;

- • nutrient recycling increases owing to particulates bound to bottom sediments are redistributed in the water column (Peters and Cattaneo, 1984).

The latter could be a particularly relevant mechanism in the case of oligotrophic shallow lakes where, because of low SRP levels, available P sorbed to sediment particles could be released and alter the lake trophic status as detected by Peters and Cattaneo, 1984, in more productive systems. However, the contribution of biotic and abiotic processes in SRP release and uptake from resuspended matter has been scarcely studied (Boström, 1984; Dorioz et al., 1998; Golterman, 2004). Furthermore, the relevance of sediment resuspension in oligotrophic high mountain lakes located in the Mediterranean area may be amplified as a consequence of the extreme natural fluctuations in their water levels, which may be favored by global warming. In fact, climate change will increase the recurrence of extreme weather events such as drought and heavy rainfall (Jentsch and Beierkuhnlein, 2008).

In addition, and apart from the upward resuspension flux, settling material could also be a significant source of dissolved nutrients through mineralization processes, thus being a relevant component of recycled production (Gálvez and Niell, 1993). In P-limited lakes, however, the settling seston could act as a sink of P (de Vicente et al., 2005; Gächter and Mares, 1985; García-Ruiz et al., 2001). Despite the relevance of settling matter in the nutrient dynamic, it is still debated whether settling particles are a sink or source of P and whether this is dependent on the trophic state of the water body (de Vicente et al., 2008).

The effect of sediment resuspension and sedimentation on SRP dynamics is of particular concern for high mountain lakes, which represent remote, oligotrophic systems where the external load of nutrients is extremely low (Cruz-Pizarro and Carrillo, 1996; Villar-Argaiz et al., 2001). Accordingly, the aims of this article are:

- • to examine the SRP release or uptake by settling and resuspended matter;

- • to discriminate between the biotic and abiotic contribution for such processes in two Mediterranean oligotrophic high mountain lakes located in the Sierra Nevada National Park (southern Spain).

The well-documented P-limitation of both study lakes (Morales-Baquero et al., 1999) makes the potential impact of sediment resuspension and mineralization of settling matter on SRP availability a relevant topic in these pristine systems.

2 Material and methods

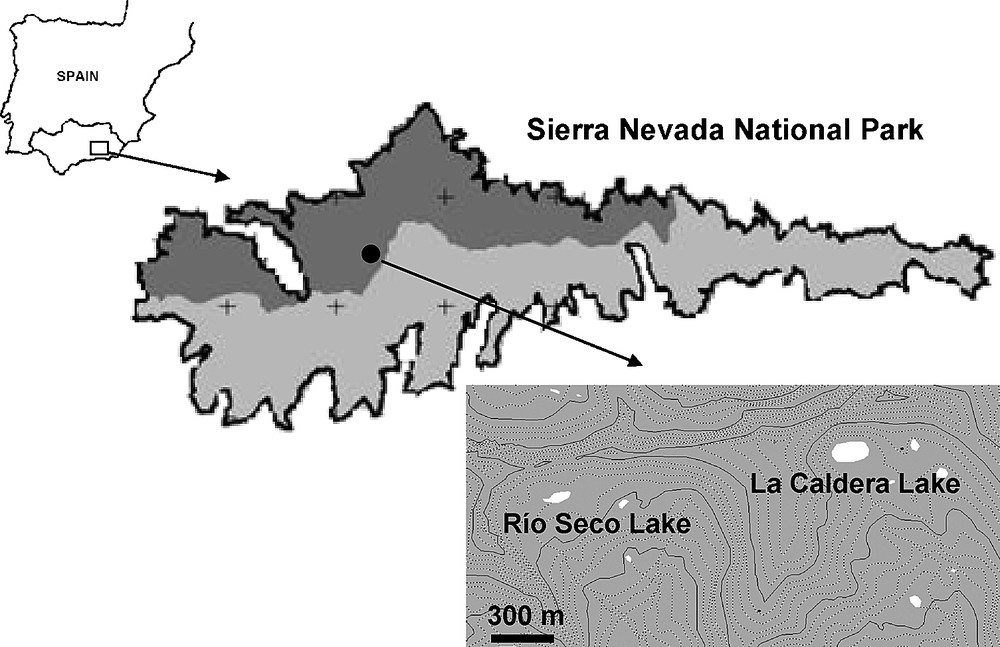

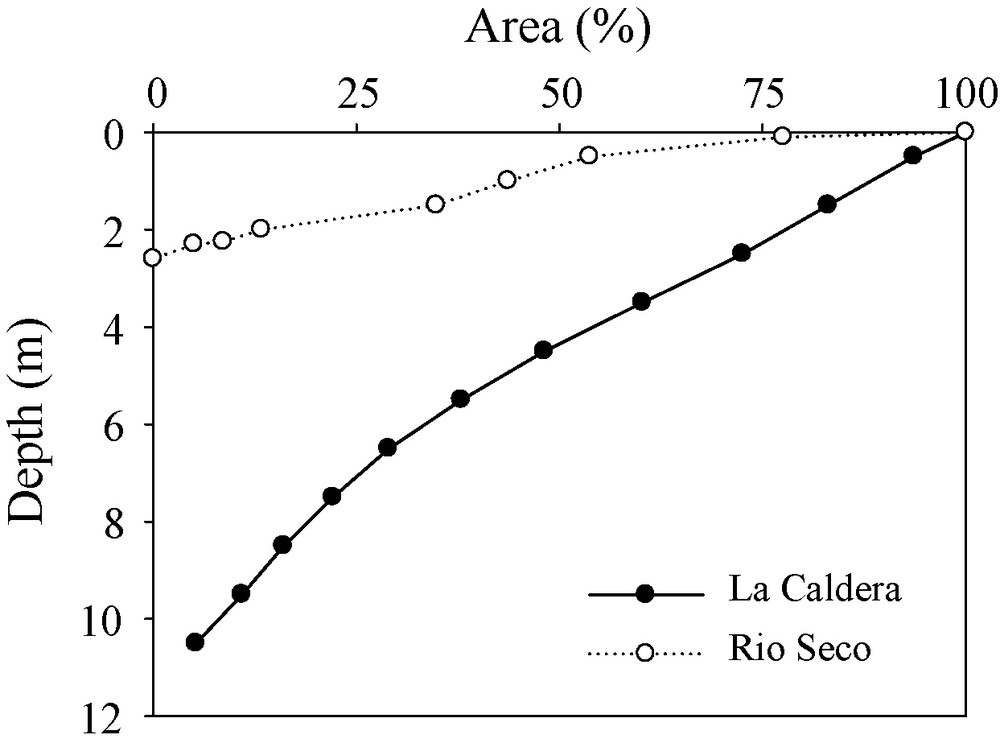

For this study, two Mediterranean oligotrophic high mountain lakes located in the Sierra Nevada National Park (southern Spain): Río Seco (RS) and La Caldera (LC) were selected (Fig. 1). They clearly differ in watershed and in hydrological and morphometric features (Morales-Baquero et al., 1999; Reche et al., 2001) (Table 1). As a way of illustration, under maximum water storage, a large fraction of RS (> 90%) is shallower than 2 m, while in LC, at those circumstances, most of the basin is deeper than 2 m (only 25% is shallower than 2 m) (Fig. 2). Although both study lakes are subjected to the same Mediterranean climate, LC is much more dependent on rainfall patterns than RS, where water storage is more stable over years (Pulido-Villena, 2004). This study was performed in a dry period (summer 2005 and 2006) when the maximum depth recorded in LC and RS was just 2 m.

Geographic location of the study lakes.

Position géographique des lacs étudiés.

Caractéristiques générales des lacs étudiés (1,2 d’après [Pulido-Villena, 2004; Pulido-Villena et al., 2003]).

| Río Seco | La Caldera | |

| Location UTM (30S)1 | VG694009 | VG708012 |

| Altitute (m a.s.l.)1 | 3020 | 3050 |

| Area (AL ; m2)1 | 4200 | 21,000 |

| Maximum depth (m)1 | 2.0 | 14.0 |

| Catchment area (AC, m2)1 | 99,000 | 235,000 |

| Maximum volume (V, m3)1 | 1185 | 107,600 |

| AC : AL | 23.57 | 11.19 |

| Hollow coefficient (m : √AL) | 0.03 | 0.10 |

| Tot-P (μg/l)2 | 15.5 | < 15.5 |

| Chl-a (μg/l)2 | 1–3 | < 2 |

Areal hypsographic curves of La Caldera and Río Seco under maximum water storage (modified from [de Vicente et al, in preparation]).

Courbes de la distribution des surfaces en fonction de la profondeur pour les lacs de la Caldera et de Río Seco, lorsque le niveau des eaux est maximum ([de Vicente et al, in preparation]).

In order to study the sedimentation processes in LC and RS, sediment traps for collecting settling material were deployed at two different depths (1 and 1.7 m). The traps consisted of twin-Plexiglas cylinders, with an aspect ratio (H:D = 30 × 4.4 cm) higher than six (Bloesch and Burns, 1980). Settling matter was collected during different periods ranging from 4 days to 4 weeks in the ice-free period of 2005 and 2006 (Table 2). In the laboratory, the suspension was filtered through Whatman GF/C glass fibre filters and dried (104 °C, 24 hours). The sinking flux of particulate material (S, g DW/m2/d) was calculated according to:

| (1) |

Périodes où ont été collectés les dépôts de matière en suspension.

| Dates | |

| 2005 | 30 June–4 July (Period I) |

| 4–21 July (Period II) | |

| 21 July–12 August (Period III) | |

| 12 August–5 September (Period IV) | |

| 2006 | 29 June–27 July (Period V) |

| 27 July–14 August (Period VI) | |

| 14 August–27 September (Period VII) |

where M is the mass of particulate material quantified as the difference in dry weight of filters before and after filtering a known volume (VF) of the homogenized entrapped suspension; VT is the trap volume, 0.45 l; A is the collection area, 15.2 cm2 and T is the time of trap exposure.

In July 2005, resuspended matter (flocculent layer) was sampled using a horizontal Van Dorn sampler, which was bounced off the bottom a few times to resuspend the sediment (Doremus and Clesceri, 1982). Organic matter content (%) and Tot-P were determined in both the settling and resuspended matter used for this experiment. Organic matter content was quantified by dry combustion (450 °C, 3 hours). Tot-P was determined by combustion (450 °C, 3 hours) of 0.1 g of dry material followed by hot 1 M HCl extraction (104 °C, 1 hour) (Paludan and Jensen, 1995). Finally, the molybdenum reactive P was quantified in the supernatant by spectrophotometry (Koroleff, 1983).

A laboratory experiment was conducted, in July 2005 (period I), with the settling material collected by the upper traps (1 m) and with the resuspended matter of both study lakes. Suspensions (100 ml) were prepared by mixing 50 ml of filtered lake water and 50 ml of resuspended/settling matter in order to get similar concentrations of total suspended solids as those measured during resuspension events (5 ± 1 mg/l). Suspensions were shaken (150 rpm) and incubated in darkness (15 ± 2 °C) for 7 days in 125 ml polyethylene flasks. Laboratory conditions were selected in order to represent the average in situ conditions near the bottom of both studied lakes. At different times (0, 1, 3, 5 and 7 days), 15 ml of each homogenized suspension was removed and filtered through glass Whatman GF/C fibre filters. Then, SRP concentration remaining in solution was measured following (Murphy and Riley, 1962). We have used in the whole text the term “SRP” instead of “PO4−3” as PO4−3 is an ionic species included in SRP and is the main species only if pH is higher than 12. To discriminate between abiotic and biotic processes, we added a treatment where biological activity was inhibited using sodium azide (200 mg/l), which has been identified as a more effective inhibitor of bacterial activity than formaldehyde (Callieri et al., 1991). Lake water was also incubated with and without sodium azide. Hence, the treatment measures only abiotic processes such as adsorption/desorption, while the control (untreated) representing natural conditions measures both biotic (bacterial uptake/release) and abiotic processes. All experiments were run in oxic conditions and in triplicate.

Correlation analyses were performed using Statistica 6.0 Software (StatSoft Inc., 1997). For t-tests Student, unless otherwise stated, the significance level was set at P < 0.05. For the laboratory experiment performed with settling and resuspended material, the differences between experimental treatments were assessed by a repeated measures one-way Anova.

3 Results

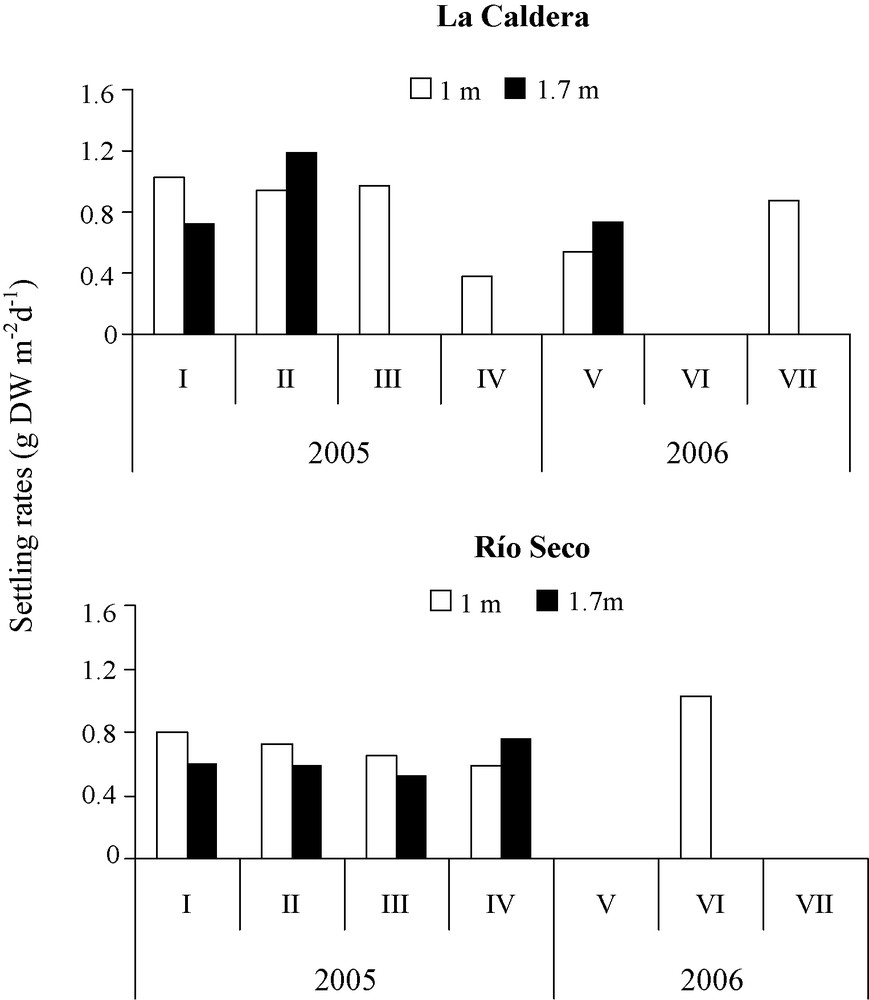

During the ice-free period of 2005 and 2006, both study lakes showed similar (P > 0.05) settling rates, ranging from 0.38 to 1.18 g DW/m/d (Fig. 3). No significant vertical nor temporal differences have been observed in settling rates.

Temporal variation of settling flux in La Caldera and Río Seco at two different depths (1 and 1.7 m), during the ice-free period of 2005 and 2006.

Variation temporelle du flux de décantation de matière en suspension dans la Caldera et dans Río Seco, à deux profondeurs différentes (1 et 1,7 m), au cours de la période libre de glace de 2005 et 2006.

As Table 3 shows, similar patterns in the chemical composition of settling and resuspended matter in LC and RS were observed. Accordingly, settling matter was significantly more enriched in organic matter than resuspended matter while Tot-P concentration was lower in settling matter than in resuspended matter in both study lakes. A possible explanation for the high organic matter content in the settling matter despite of the low chlorophyll-a values, is the contribution of large zooplankton (i.e. Daphnia pullicaria and Mixodiaptomus lacinatus), which generally dominates the zooplankton community (Cruz-Pizarro and Carrillo, 1996; Villar-Argaiz et al., 2001).

Caractérisation générale de la décantation et des matières remises en suspension.

| Rio Seco | La Caldera | |

| Settling matter | ||

| Tot-P (μg/g DW) | 312 ± 52 | 449 ± 83 |

| OM (%) | 65 ± 4 | 63 ± 7 |

| Resuspended matter | ||

| Tot-P (μg/g DW) | 1133 ± 81 | 820 ± 52 |

| OM (%) | 12 ± 2 | 10 ± 2 |

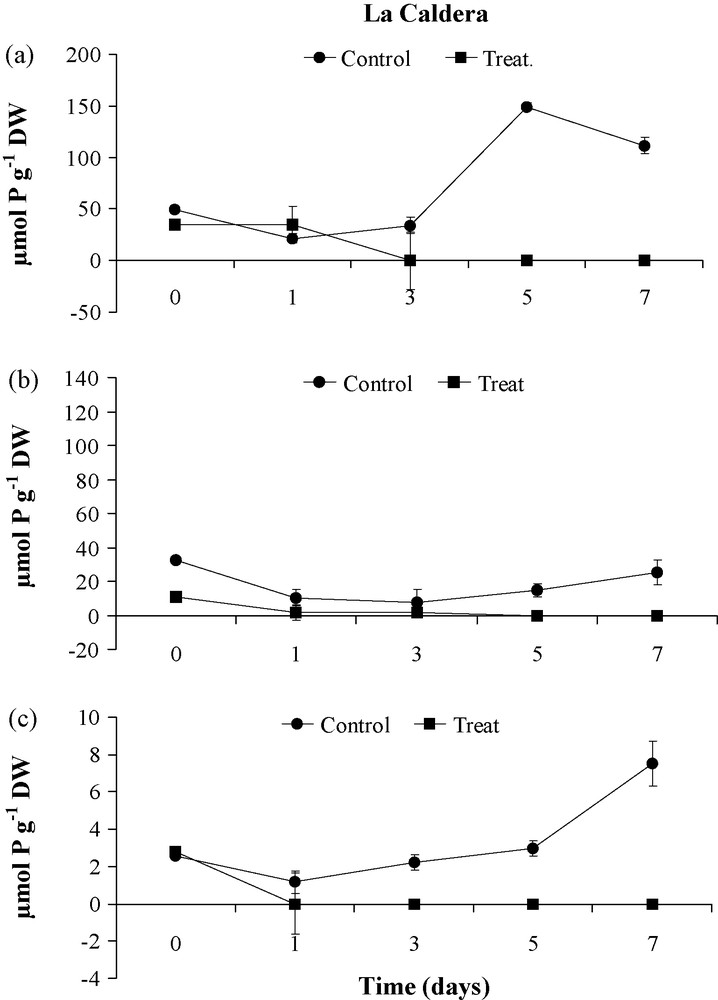

Incubation experiments with LC samples showed no SRP in solution (no release) in the control with untreated lake water or lake water enriched by settling and resuspended matter (Fig. 4a-c). However, the treatment with sodium azide showed significantly higher (P < 0.05) SRP concentrations in all three tested solutions. The initial P-contents in the treatments may be caused by the applied sodium azide known to cause bacterial cell lysis. The SRP increase towards the end of experiment was significant (P < 0.005) in untreated lake water and lake water enriched with resuspended matter, while it was not (P > 0.05) with lake water enriched with settling matter.

Temporal change of the mass of SRP (μmol P) present in solution by unit of mass of dry weight of particulate material in La Caldera: a: lake water; b: lake water enriched with settling matter; c: lake water enriched with resuspended matter. Treatment: addition of sodium azide (200 mg/l) to inhibit biological activity. SD is shown by vertical bars. Note the different scales of y-axis.

Variation temporelle de la masse de SRP (μmol P) présente en solution, par unité de masse de poids sec de matières en suspension à La Caldera : a : eau du lac ; b : eau du lac enrichie avec de la matière sédimentée ; c : eau du lac enrichie avec de la matière en resuspension. Traitement : addition d’azide de sodium (200 mg/l) pour inhiber l’activité biologique. L’écart-type est donné par des barres verticales. Notez les différentes échelles de l’axe des ordonnées.

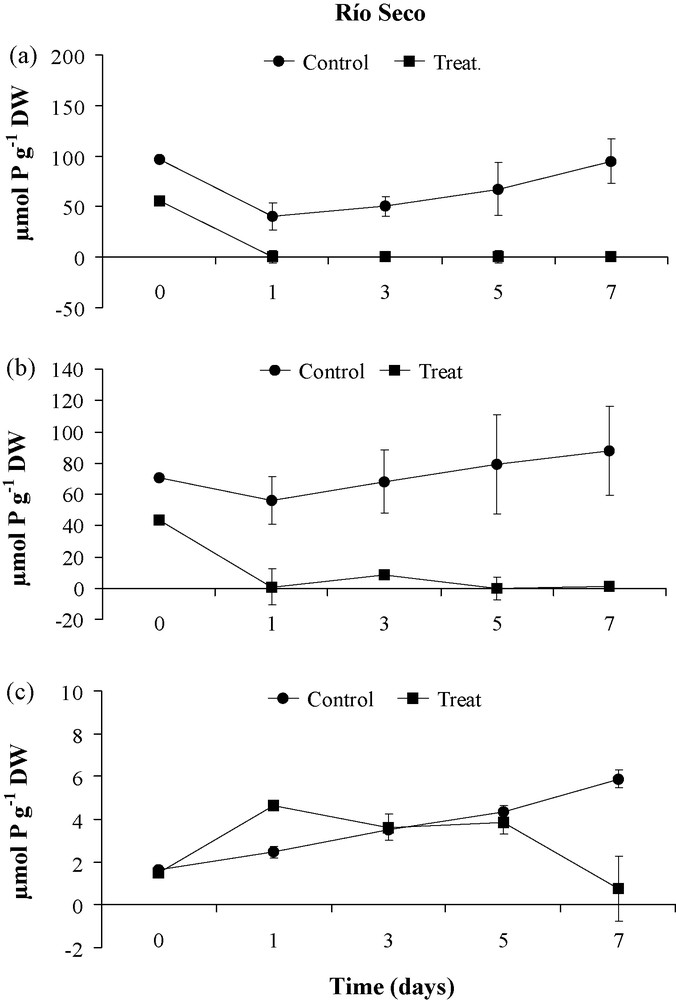

In RS experiments, and similarly to LC experiments, the control showed no SRP concentrations in lake water (Fig. 5a) and lake water enriched with settling matter (Fig. 5b) indicating SRP adsorption and possible biological consumption. In contrast, addition of resuspended matter led to an increase of SRP during the first 24 hours, followed by a continuous decrease to a minimum on day 7 (Fig. 5c).

Temporal change of the mass of SRP (μmol P) present in solution by unit of mass of dry weight of particulate material in Río Seco: a: lake water; b: lake water enriched with settling matter; c: lake water enriched with resuspended matter. Treatment: addition of sodium azide (200 mg/l) to inhibit biological activity. SD is shown by vertical bars. Note the different scales of y-axis.

Variation temporelle de la masse de SRP (μmol P) présente en solution, par unité de masse de poids sec de matières en suspension à Río Seco : a : eau du lac ; b : eau du lac enrichie avec de la matière sédimentée ; c : eau du lac enrichie avec de la matière en resuspension. Traitement : addition d’azide de sodium (200 mg/l) pour inhiber l’activité biologique. L’écart-type est donné par des barres verticales. Notez les différentes échelles de l’axe des ordonnées.

Similar to LC, the treatment with sodium azide increased SRP concentrations significantly (P < 0.05) when lake water was enriched with settling matter (Fig. 5b) and also for lake water itself (Fig. 5a). Lake water enriched with resuspended matter showed similar concentrations as the control (Fig. 5c); however, the change over time was opposite, and final SRP concentrations were significantly (P < 0.05) different. This shows a net retention of SRP in the control and a net release in the treatment.

4 Discussion

Daily settling rates measured in this study are in the range of those reported in the literature for oligotrophic systems (Tartari and Biasci, 1997). These low values for settling rates also confirm the positive relationship between trophic state and settling flux in natural water bodies (de Vicente et al., 2005).

The study of the interaction between the solid particles (suspended, settling and resuspended matter) and the solution is complex but crucial for the case of oligotrophic lakes where external nutrient load is especially low and, therefore, internal nutrient recycling may represent a key source of nutrients that ultimately control primary production. This complexity is even greater if we consider that notable seasonal changes in the chemical characteristics of settling matter can occur as a consequence of phytoplankton succession, the mixing conditions and sorption-desorption processes during sedimentation (Gächter and Mares, 1985; Pettersson, 2001).

Our experiments showed that the effect on P-release of resuspended matter was about an order of magnitude smaller than that of settling matter and untreated lake water (demonstrated by the different scales of y-axis in Figs. 2 and 3). This makes sense as the resuspended material has undergone more decomposition than fresh settling matter. In fact, organic matter concentrations in resuspended and settled matter were, respectively, 12% ± 2 and 65% ± 4 in RS and 10% ± 2 and 63% ± 7 in LC.

This study has revealed notable differences in the effect of sediment resuspension on SRP dynamics in two oligotrophic high mountain lakes and thus highlights the need for in situ studies. First, when not adding the biological inhibitor (sodium azide), that is, simulating the natural conditions when lake water is enriched with settling matter and with resuspended matter, no increase in SRP concentrations in lake water was noticed in LC. By contrast, in RS the input of resuspended matter causes a short-term release of SRP from the particulate to the dissolved pool but an uptake over the 7 days of the experiment. One likely interpretation is that bacterial growth along the experiment contributed to an increasing P removal from lake water. However, it is relevant to note that SRP concentrations in RS at the end of the experiment are significantly higher (P < 0.05) in lake water enriched with resuspended matter (3.2 μg/l) than in natural lake water (lower than the detection limit) suggesting an important effect of sediment resuspension on SRP availability in this oligotrophic lake. One possible explanation for the differences observed in the effect of lake water enrichment with resuspended matter between both study lakes emerges from the chemical composition of the resuspended matter (Table 3). If we consider that 2.4 g of the dry organic matter contain 1 g of C (Margalef, 1983), we can estimate that the Organic Carbon to Tot-P molar ratio is slightly higher in resuspended matter of LC (131) compared with RS (114), which could explain the stronger bacteria P limitation in LC compared with RS. In this sense, and as data compiled from literature show (Hochstädter, 2000), the relatively low C:P ratios of bacteria, as compared with other organisms, cause them to be frequently P-limited. As a consequence, biological activity occurring in resuspended matter of RS tends to release SRP more than in LC.

The relevance for these results is even more important if we consider that the hollow coefficient (maximum depth divided by the root square of the lake area) is more than three times lower in RS than in LC (Table 1) and that, as we have mentioned above, RS is much shallower than LC (Fig. 2). Accordingly, it is reasonable to expect that sediment resuspension occurs more frequently in RS compared with LC and as we have shown in the present study, this affects drastically the SRP availability in the water column.

Next, we try to clarify the role of biotic and abiotic processes in the release or uptake of SRP by settling and by resuspended matter. In LC, the higher SRP levels in preparations with treatments (addition of sodium azide) compared with controls, for both resuspended and settling matter, suggest that biotic activity is playing an important role in SRP uptake from the solution to the particulate matter. Biological uptake from settling and resuspended matter is likely to be the result of bacterial P limitation, in which bacteria tend to uptake P more than release it to the solution during organic matter mineralization in order to satisfy their own metabolic requirements. This pattern has also been described previously (Clavero et al., 1999; Gächter and Mares, 1985; Watts, 2000). In RS, a similar pattern was observed when lake water was enriched with settling matter; however, no differences between control and treatment were found when lake water was enriched with resuspended matter. This is likely to show that bacteria are not so P limited. Accordingly, our results show that even when biological activity is taking place on resuspended matter, which occurs under natural conditions, SRP tends to be rapidly desorbed from the particulate to the dissolved pool and the final effect of sediment resuspension on SRP availability in the water column will depend on the time that particles remain in solution.

Finally, we conclude that further research on the specific role of attached living bacteria on the uptake/release of P from the settled and resuspended material at different times is needed.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the project OAPN 129 A/2003 (Environmental Ministry of Spain). We thank Prof. Jürg Bloesch for his useful and interesting comments for improving the manuscript, and Dr. Dorioz, Pr. Sarazin and an anonymous reviewer for their comments on an earlier version of this article. The experiments carried out in this study comply with current Spanish laws.