1 Introduction

Mass Transport Complexes (MTCs) and Mass Transport Deposits (MTDs) have been identified both in ancient and modern deep-water systems and can represent a significant percentage of deep-water deposits along the continental margins (Shipp et al., 2011). MTD is a general term that refers to slumps, slides and debris/mud flow deposits (Nardin et al., 1979), generated by sediment failures and emplaced by mass movements or cohesive gravity-controlled processes. MTDs are encountered on most continental margins around the world and are distinctive in submarine depositional systems because of their large size, particular morphology and chaotic internal character on seismic lines (Shipp et al., 2011). MTDs movement and emplacement are generally associated with different degrees of brittle or plastic deformation (Nelson et al., 2011) such as microfaults following a phase of ductile deformation forming sheath folds or fold boudins (Posamentier and Martinsen, 2011). The main fold style in slumps is sheath folds formed by simple shear (Martinsen, 1994).

MTDs have been originally defined on the basis of seismic surveys in the Plio-Pleistocene Mississippi fan systems, where they can represent 10 to 20% of the stratigraphic record (Weimer, 1989, 1990). Amalgamated MTDs can form composite MTDs or Mass Transport Complexes (MTCs; Hampton et al., 1996; Pickering and Corregidor, 2005). They may form the substratum for the development of new channel-levee complexes, suggesting that they could have a sequence stratigraphic significance (Weimer, 1989, 1990). MTDs morphology has been well documented on several modern turbidite systems, e.g. Amazon fan (Piper et al., 1997) or Rhône fan (Bonnel, 2005; Bonnel et al., 2005; Droz and Bellaiche, 1985). They involve large volumes of debris avalanches up to thousands of cubic kilometres (5500 km3 for Storegga, Bugge et al., 1987; 1350 km3 for Hinlopen, Vanneste et al., 2006). In the Nile system, 18 MTDs with a thickness ranging from 55 to 425 m have been recently identified in the Late Pliocene–Quaternary stratigraphic interval (Rouillard, 2010). Despite being originally defined along a siliciclastic margin, they can also occur along carbonate slopes (Callot et al., 2008a; Mullins and Cook, 1986). The largest documented MTD appears to be the Ayabacas Formation (Peru) that is the result of the collapse of > 10,000 km3 due to the failure of an entire carbonate platform, related to the Andean orogenesis, at the Turonian–Coniacian boundary (Callot, 2008; Callot et al., 2008a). Facies analysis of the Ayabacas MTD shows clearly in some cases a progressive down-flow disaggregation of the failed mass from non-deformed material, to plastic deformation to final distal liquefaction (Callot et al., 2008b). Internal seismic characteristics (e.g., chaotic and/or discontinuous reflection character) have been relatively well-defined (Collot et al., 2001; Garziglia et al., 2008; Moscardelli et al., 2006). More recently, 3D seismic reflection data analysis has revealed the detailed seismic signature within MTDs and its relationships with kinematic indicators (Bull et al., 2009; Frey-Martínez et al., 2006), suggesting spatial changes in the mode of transport and progressive longitudinal disaggregation, including changes in rheological behaviour. MTC initiation can be related to slope failures linked with oversteepening and overloading processes in high sedimentation rate areas, fluid escape processes including clathrate exsolution (Storegga; Mienert et al., 2005) or induced by earthquakes. Sequential position in the stratigraphic record remains to be clearly defined, even though MTDs that originate on the upperslope due to loading or/and fluid escape processes appear to deposit preferentially during sea-level lowstand and sea-level fall (Rouillard, 2010). Conversely, those related to structural motion can occur at any stage during the sea-level cycle. Climate can also influence MTDs generation since it is amongst the major controls on the volume and the location of sediment storage on the shelf before slumping (Ducassou, 2006). MTDs are very good seismic markers and, depending on their lithological and geometrical characteristics (i.e. nature of the cohesive matrix, spatial extent and large-scale geometry), may represent stratiform seals in deep-water reservoirs. MTDs are characterized by an irregular shaped surface above which subsequent sediments can be ponded (Armitage et al., 2009; Pickering and Corregidor, 2000; Shor and Piper, 1989) and more generally their surface topography controls the architecture of the overlying deposits, such as channel-levee systems (Rouillard, 2010). In this paper, we present the outcrop signature of a 5-km3-large MTD located in the worldwide-known Annot Sandstone Formation, but never described so far. We provide a general description of the mass-flow deposits and a discussion on their potential triggering mechanisms. We also suggest the implication in terms of rate of deformation related to flexural subsidence and for the regional-scale reservoir properties.

2 General settings

The well-known siliciclastic Annot Sandstone Formation is a confined sand-rich turbidite system representing the southward Tertiary infill of the Alpine foreland basin system. Its remnants belong to the southern Subalpine fold and thrust belts (Fig. 1A), composed of the Digne thrust sheet curving to the south to the east–west-oriented Castellane Arc, itself curving eastwards into the north–south oriented Nice Arc (see Ford et al., 1999 and references therein). The present-day structural setting of the southern Subalpine belts results from the superimposed deformations related to the Pyrenean-Provençale thrust belt (Late Cretaceous to Palaeocene) and to the Alpine thrust belt (Middle Eocene to Recent). Triassic evaporites played a major role on southern Subalpine fold and thrust belts deformation behaviour, acting as widespread detachment layers, both for the Digne thrust sheet (Ford and Lickorish, 2004; Goguel, 1963; Lemoine, 1973; Lickorish and Ford, 1998; Siddans, 1979), and for the Castellane (Laurent et al., 2000) and Nice arcs (Gèze, 1960; Lanteaume, 1962). Thin-skinned thrusting and related folds within the Mesozoic cover, which shaped the Annot Sandstone basin-floor palaeotopography (Elliott et al., 1985), are also closely linked with Triassic evaporites (Apps et al., 2004). Due to this inherited topography, the Annot Sandstones are segregated into laterally confined sub-basins, their infill becoming younger westward due to the Alpine deformation front propagation (Bodelle, 1971; Callec, 2001; du Fornel, 2003; Joseph and Lomas, 2004; Sztrákos and du Fornel, 2003). Sediment supply to the Annot sandstone sub-basins is attributed to the Corsica–Sardinian Massifs (Garcia et al., 2004; Ivaldi, 1974; Jean, 1985; Sinclair, 1997; Stanley and Mutti, 1968) and to the Maures–Esterel Massif (Bouma, 1962; Ivaldi, 1971; Sinclair, 1994) for late stages of infill. Sediment flux and related sedimentation rate have been high in such a flexural basin bordering a mountainous Alpine drainage area. A mean sediment flux of 260 km3/Myr reaching punctual extreme values of 900 km3/Myr has been used by du Fornel to perform a numeric model of the filling of Saint-Antonin Basin, south of the study area. In there, flexural subsidence is filled by 400 m of deltaic deposits (du Fornel, 2003). This sediment flux could be substantially increased when the upstream part of the basin was uplifted and that depocentre rapidly migrated northwestward (du Fornel et al., 2004). Such high sediment flux led to high sedimentation rates in such confined sub-basins (Joseph and Lomas, 2004). Extensive syndepositional slumping indicative of syndepositional tectonic activity is indicated by an abundance of megabeds and reworking of older formation within the turbidite series (Apps et al., 2004). The Annot Sandstone Formation is the last member of the Nummulitic Trilogy (Boussac, 1912; Faure-Muret et al., 1956; Joseph and Lomas, 2004), related to the Nummulitic transgression, which is composed of the Nummulitic Limestone, the Blue Marls, and the Annot Sandstones. The Annot Sandstones consist of a thick series up to 1200 meters thick (Inglis et al., 1981) of gravity-flow deposits resulting from various gravity processes, from cohesive flow deposits to low-density turbidites. The investigated outcrops are situated in the Mont-Tournairet sub-basin, which is a small confined zone situated a few kilometres northwest of the Contes–Peira-Cava sub-basin (see location in Fig. 1A) and close to the towns of Roquebillière and Lantosque. In these sub-basins, numerous studies (e.g., Etienne et al., 2012; Jean, 1985; Joseph and Lomas, 2004) showed that the palaeoslope and transport direction were toward the north and then bending toward the northwest, whereas the source was located in Corsica–Sardinia, southward of the outcrops. Despite many studies and publications on the Annot Sandstone turbidite system, its related gravity deposits and the associated geological settings, very few contributions have focused on this sub-basin. This system could correspond to the westward continuation of the Contes–Peira Cava sub-basin (Fig. 1A), but their relationships remains poorly documented and understood. It has been biostratigraphically constrained to the Early Priabonian (Joseph and Lomas, 2004; Sztrákos and du Fornel, 2003). In its northern part, this system is composed of a thick sandy depocentre in its western part (“Rochers des Baus” area) which laterally evolves to a less amalgamated and sheet-like deposit dominated by a zone of onlap terminations towards the east (“Granges” area) (Etienne et al., 2012). In this paper, we focus in the south-western part of the Mont-Tournairet system, the Lantosque Mountain area (Fig. 1B).

(Colour online.) A. Regional map of the southwestern Alps with location of the Mont-Tournairet sub-basin (modified from Joseph and Lomas, 2004). B. Simplified geological map of the studied area, showing the Mont-Tournairet sub-basin, in which the three components of the Nummulitic trilogy crop out and showing the Lantosque Mountain MTD, in the vicinity of the town of Lantosque (modified from French BRGM Geological Maps “Puget-Théniers” (Faure-Muret et al., 1957) and Saint-Martin-Vésubie–Le Boréon (Faure-Muret et al., 1967)). VF: Vésubie Fault. Location according to Schreiber (2010). C. Topographic map showing the extent and the dimensions of the slumped area of the Lantosque Mountain. The Breil-Sospel-Monaco (BSM) strike-slip fault system is the fault system located between Nice, Menton and Contes. Masquer

(Colour online.) A. Regional map of the southwestern Alps with location of the Mont-Tournairet sub-basin (modified from Joseph and Lomas, 2004). B. Simplified geological map of the studied area, showing the Mont-Tournairet sub-basin, in which the three components of the Nummulitic ... Lire la suite

3 Deposits of the Lantosque Mountain: facies description

The Lantosque Mountain is composed of two types of main lithofacies. The complete preserved sedimentary series is approximately 600 m thick and outcrops between present isohyps 500 m and 1100 m (Fig. 1C). This represents the maximum preserved thickness given the high deformation level. The undeformed lithofacies forms the smallest part (< 10%) of the whole mountain. It stratigraphically occurs at the base and at the top of the sedimentary series. Conversely, the deformed lithofacies (facies 1 to 3) represents the majority of the mountain volume.

3.1 Undeformed lithofacies

As the Upper Eocene to Lower Oligocene outcrops of the Lantosque Mountain stratigraphically belong to the Annot Sandstones, they consist of very typical Lowe (1982) and Bouma (1962) sequences corresponding to hyperconcentrated, concentrated and more diluted turbulent flow deposits (sensu Mulder and Alexander, 2001). Indeed, Bouma top cut-out sequences are abundant, made up of thin-bedded laminated and/or rippled sandstones to siltstones (Bouma Tbc sequences, Bouma, 1962) that alternate with hemipelagic muds (Fig. 2A). These alternations are organized into thick heterolithic packages. Erosive-based, essentially structureless, very coarse to fine-grained graded sandstones deposited by hyperconcentrated to concentrated flows (sensu Mulder and Alexander, 2001) are also present, and define thick homolithic packages. Their constituent facies correspond to S1 to S3 intervals of Lowe sequences (Lowe, 1982) or to Mutti's F4 to F8 facies (Mutti, 1992).

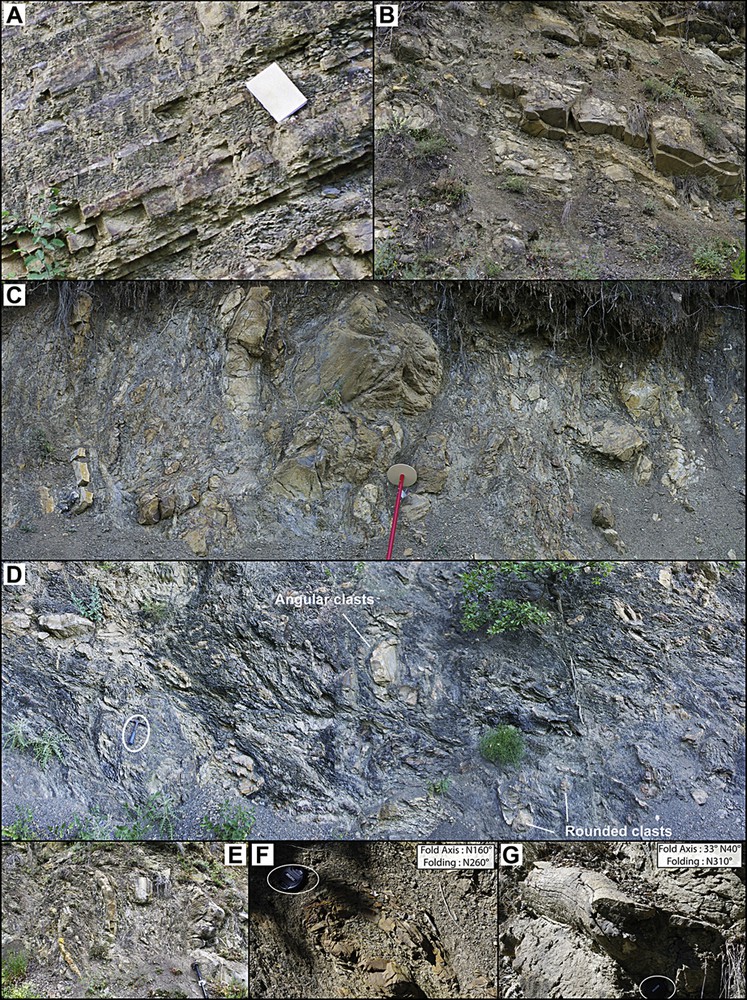

(Colour online.) A. Typical thin-bedded turbidite facies of the Annot Sandstones in the Mont-Tournairet sub-basin, Lantosque Mountain. B. Illustration of Facies 1, showing rafted blocks of plurimetrical-scale discontinuous homolithic to heterolithic intervals (rafted blocks) overlying a facies-3 interval. C. Facies 2: metrical to decimetrical sandy blocks in a shaly matrix with a preferential orientation of clasts, parallel to original bedding. D, E. Examples of slumped and highly deformed deposits (facies 3), Lantosque Mountain MTD. D. Plurimetrical to decimetrical sandy blocks in a shaly matrix, with abundant folded and contorted horizons. E. Example of metric-scale folded intervals. F, G. Evidence of plastic deformation affecting thin-bedded strata of facies 3. Slump folds axes and directions were measured among the Lantosque Mountain. Masquer

(Colour online.) A. Typical thin-bedded turbidite facies of the Annot Sandstones in the Mont-Tournairet sub-basin, Lantosque Mountain. B. Illustration of Facies 1, showing rafted blocks of plurimetrical-scale discontinuous homolithic to heterolithic intervals (rafted blocks) overlying a facies-3 interval. C. Facies 2: metrical ... Lire la suite

3.2 Deformed lithofacies

Almost the whole Lantosque Mountain (see location in Fig. 1) is made of thick deformed deposits corresponding to chaotic breccias and conglomerates, with sandy to silty clasts of variable dimension, floating in a shaly matrix. Three main facies are distinguished from these breccias and conglomerates, based on the degree of their internal organisation and on the size of the floating clasts. The three facies show alternation of thin-bedded soft deposits and more massive sandstone suggesting a common source that is similar to the usual source of the Annot Sandstone formation.

3.2.1 Facies 1: large volume slides/rafted blocks

This first facies is composed of discontinuous but stratified packages of homolithic and heterolithic facies (multi-metre blocks; Fig. 2B). They are embedded within facies 2 and 3 deposits (see following text). This facies corresponds to brittle mass-movement deposits (slides), characterized by large-scale blocks, and composed of turbidite facies without any internal plastic deformation. They correspond to voluminous sediment collapses that resulted in the resedimentation of rafted blocks.

Facies 2 and 3 are quite similar but they contrast in terms of level of internal deformation and transport distance interpretations.

3.2.2 Facies 2: stratified breccias

These brecciated units show an internal organisation, as clasts exhibit a preferential orientation (facies 2, Fig. 2C). Indeed, clasts are subparallel, which is most probably linked with a previous stratification that is partly preserved. In some places internal stratification still appears, suggesting that clast orientation is related to initial bedding rather than to a reorientation within a ductile matrix parallel to the extension direction. This facies involves a plastic deformation appearing under the form of disharmonious folds, but more likely with a short amount of transport distance, which induces the preservation of the original bedding.

3.2.3 Facies 3: chaotic breccias

These deformed units (facies 3, Fig. 2D) share very similar characteristics with facies 2 (stratified breccias), but they are made up of variable-size clasts (boulders up to several meters), of heterogeneous grain size (from very coarse-grained sands to silts) clasts, floating in a shaly matrix. The clasts are mostly rounded, but they can sometimes be angular. These sedimentary breccias and conglomerates are characterised by a very chaotic organisation and by the absence of any stratification, which suggests a significant plastic deformation and a transport over at least a small distance, allowing the destruction of the original bedding. They show disorganized material in which contorted, slumped and small-scale thrusted horizons usually occur. Most of the folds are disharmonious folds with a 3D geometry and a curved hinge (sheath folds; Fig. 2E). These folds preferentially affect thin-bedded stratas, whereas thick-bedded units are resedimented through discontinuous unfolded plurimetrical blocks (facies 1). This folding is also present in the shaly matrix, and is emphasised by a slight schistosity. In terms of spatial extent, nature of matrix and clasts and more importantly stratigraphic thickness (several decametres), this facies is different from the debris flow facies that have been described and used as regional scale key-markers in the Restefond–Sanguinière area (Jean, 1985; Ravenne et al., 1987).

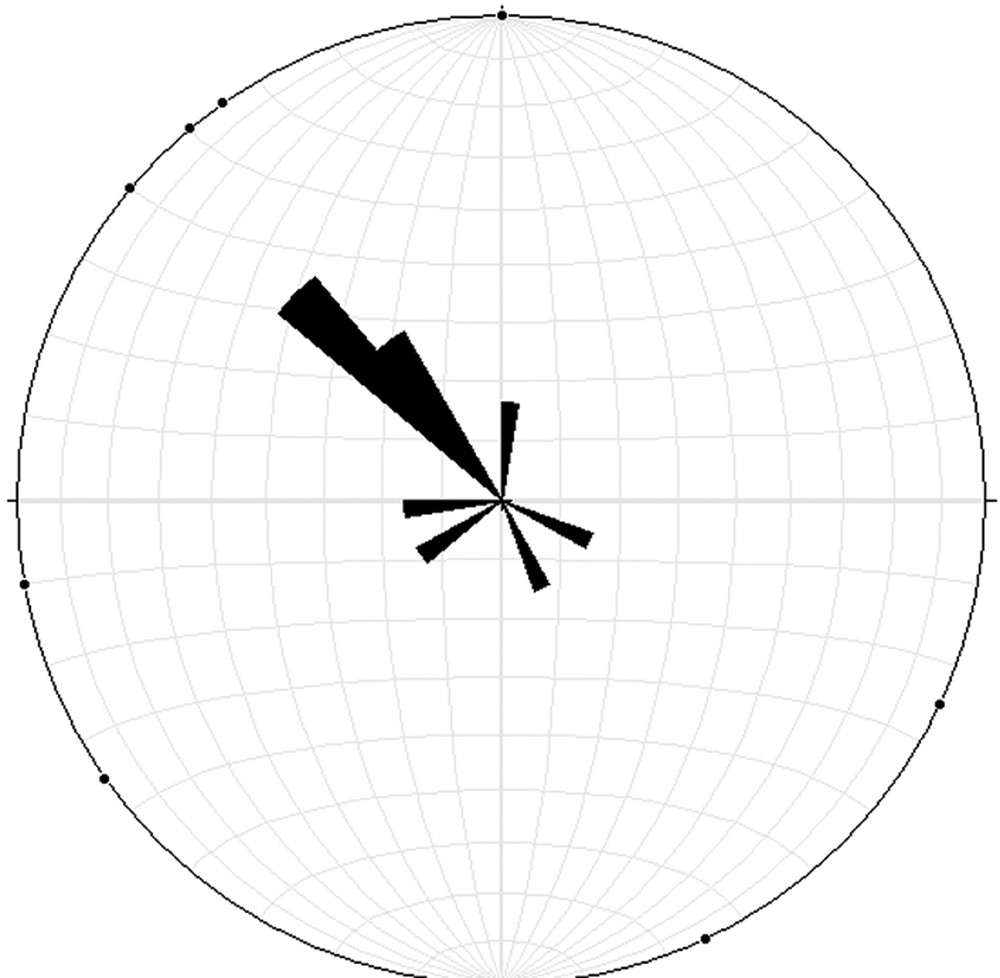

3.2.4 Transport direction evidences

In MTDs, direction of movement and consequently palaeoslope are difficult to assess (Strachan and Alsop, 2006). Criticisms concerning the direction of folding to infer motion direction of slumped masses have been made by Woodcock (1976, 1979a, b) mainly because of the morphologic convergence between structural and sedimentary fold geometry. However, this author points out that the difficulty to distinguish one from the other increases when the size of fold slump exceeds the outcrop size, which is not the case in this study. We consequently applied the methodology suggested by Strachan and Alsop (2006), i.e. to perform measurement of all directional structures (we compared directions made of fold with those provided by erosion mark on autochthonous deposits) and to do measurement over the largest possible number of structures. The three facies show high levels of deformation at a metric scale suggesting that they correspond to mass transport deposits. Despite the disappearance of original bedding (facies 3; Fig. 2E), no deposit showing complete disaggregation of the blocks is found, suggesting short transport distance from original source location. Slump folds axes and folding directions were measured in the Lantosque Mountain outcrops, in well-developed chaotic breccia intervals within facies 3 (Fig. 2F and G). Despite a relatively restricted number of measurements due to outcrop conditions (principally vegetation cover in this area), measurement plotting indicate a clear SE–NW deformation trend (Fig. 3). In this paper, the measured folds are at the metric scale. The direction provided by these slump folds is consistent with the published direction of turbidite transport in the adjacent Contes–Peira-Cava sub-basins using classical sole mark interpretations (Joseph and Lomas, 2004 and publications therein). They are also consistent with the direction of erosion structures found in the non-deformed turbidite beds located at the base of the slumped series in the same sub-basin. This consistency suggests that the folds indicate a progressive slump motion that occurred in a northwestward-trending direction.

Rose diagram in which fold axes and folding directions were plotted (n = 25), indicating a NW-SE deformation trend despite a relatively restricted numbers of measurements due to outcropping conditions.

4 Discussion: mass flow processes and triggering mechanisms

4.1 Flow transformation and flow direction

The three different facies are interpreted to represent different stages of deformation related to variable transport distance, mechanism and emplacement processes. Facies 1 and facies 2 represent immature stages of mass-flow processes. Facies 1 is characterized by internally undeformed blocks that deposited rafted blocks emplaced by very short run-out distance slumping of more rigid material. Facies 2 is affected by plastic deformation but conservation of bedding suggests that it was also affected by a very short distance transport. Facies 3 (chaotic breccias and conglomerates with slumped and contorted intervals) are most probably the result of debris flow processes that imply sediment transport over longer distances, enhanced by matrix strength (Middleton and Hampton, 1973). In this facies, folding indicates unequivocal homogeneous synsedimentary deformation along a slope transport direction. The direction of deformation is consistent with the slope synsedimentary syncline flank in this region and with main stress direction (Schreiber, 2010). These three main facies suggest progressive disintegrating landslide in a submarine environment similarly to the case study of Callot et al. (2008a, b). The detailed mapping shows that the distribution of the three sedimentary facies is poor organisation. This is partly due to the lack of outcrop outside trails but, however, the three facies appear to be very close to each other suggesting that differentiation from slide or slump to debris flow can occur locally within the MTC without involving all the slumping mass, as this happens when a mass failure affects a whole continental slope (Callot, 2008). In addition, basin confinement prevents the development of longitudinal differentiation. Depending on the flow, including relative proportion and nature of clasts and relative proportion and nature of matrix, the differentiation can occur locally. In this case study, the local differentiation predominates over the global flow differentiation because of the confinement of the process along the syncline walls: because of the syncline structure, the rheologic transformation cannot affect the whole mass, as it could occur on a long-dipping slope.

4.2 Mass flow triggering

In the Lantosque Mountain, no surface has been detected in the whole deformed area. Consistently, no part of undeformed (autochthonous) series is observed within the slumped mass, except in well-defined transported blocks and as continuous series at the base and at the top of the deformed mass. This strongly suggests that the deformation occurred in a single movement and that we have to consider that the Lantosque Mountain forms a single MTD rather than a succession of slumped deposits forming a MTC. In addition, because the mass transport deposits represent most of the filling of the Lantosque syncline sub-basin, the mass transport processes and the resulting deformed facies could have been triggered by the gravity collapse of the whole Lantosque sub-basin, due to very high sedimentation rates in an active setting (tectonic sub-basin). The direct supply by a fluvial system and the combined uplift of the upstream part of the basin suggest high sediment load, leading to high sedimentation rates in such a confined basin. Indeed, it is known that significant internal deformation within the Digne thrust sheet occurred during Early to Mid-Oligocene (Ford and Lickorish, 2004; Lickorish and Ford, 1998) and the close interplays of gravity-flow deposits and structural deformation has been well demonstrated in the Grès d’Annot sub-basins (Callec, 2001; Salles, 2010; Salles et al., 2011 among others). This synsedimentary activity could also have induced earthquakes, which could be an alternate triggering mechanism of these mass-flow processes. Nevertheless, the vicinity with the Lantosque fault (part of the larger scale Vésubie fault, Fig. 1B) along which crops out Triassic gypsum and dolomite (Keuper) could have been the most probable triggering mechanism. Courboulex et al. (2007) showed the recent (Quaternary) activity of neighbouring faults that are satellite faults of the Breil–Sospel–Monaco strike-slip fault system that represents the eastern site of the Nice east–west-folded thrust arc (Fig. 1B). This diapir structure is situated on the eastern margin of the Lantosque Mountain sub-basin. Keuper gypsum structural role and its eventual remobilisation in the Alpine deformations during Cenozoic have been suggested by some authors (Laurent et al., 2000; Mascle et al., 1988) and could have led to a significant deformation of the basin east sides. The mean movement direction (NNW) suggested by the slump fold measurements is consistent with this hypothesis of a basin slope steepening eastward. This tectonic activity associated with the presence of underlying mobile gypsum sole is also associated with a high sedimentation rate relative to the high sediment load provided by the Corsica–Sardinia mountainous fluvial source, emphasized by confinement. Indeed, previous authors estimated the Annot Sandstone Formation mean sedimentation rate around 250–350 m/Myr in the Restefond–Sanguinière sub-basin (du Fornel et al., 2004; Guillocheau et al., 2004 based on du Fornel, 2003; Sztrákos and du Fornel, 2003) or Annot Sandstone Formation mean sediment supply up to 200 to 1000 km3/Myr for the Annot–Trois-Évêchés sub-basin (Euzen et al., 2004). These high sedimentation rates are consistent with the presence of a large volume of underconsolidated sediments prone to failure when synsedimentary deformation occurs.

5 Conclusions

This contribution provides a description of a large-scale MTD forming in the Mont-Tournairet sub-basin. Our interpretation, suggesting local transformation from a slide to a more plastic and even fluidal rheology, is supported by coherent synsedimentary fold directions and sedimentary facies. The MTDs have three main facies that are distinguished depending on the internal organisation of the deformed intervals. These three facies are interpreted to represent different states of deformation and disintegration: debris flow processes and gravity-driven slides. In the latter case, the whole MTD did not completely disintegrate and transformed into a mass flow because of the confinement and the small extent of the sub-basin (< 30 km). The deformation of Triassic gypsum along the Vésubie fault could have played an important role in the initiation mechanism of these mass transport processes. The large size of the failed mass would be the result of a high sedimentation rate related to an active sediment load from a mountainous fluvial source above a mobile evaporite layer affected by large-scale tectonic deformation in an active tectonic context (synsedimentary deformation). The Mont-Tournairet example shows that active foreland sub-basins can form and fill very rapidly, suggesting that local (at the sub-basin scale) flexural subsidence can generate high local deformation rates having a direct impact on the sediment facies distribution and sediment deposit geometry. Our study shows that MTDs can sporadically occur in sedimentary series and be used as stratigraphic markers of periods of increased tectonic activity and basin deformation.

Acknowledgments

Prof. Fabiano Gambieri and Prof. Benjamin Kneller are fully acknowledged for their constructive comments and suggestions on the manuscript. Authors wish to thank O. Teboulle and A. Pace for their help during field measurements and V. Hanquiez for artwork. Fieldwork and S. Etienne's PhD were funded by TOTAL and GDF-SUEZ companies.