1. Introduction

The Northern Mozambique Channel lies between the east coast of Africa and the northern tip of Madagascar, where the Comoros Islands form an archipelago of four volcanic edifices (Figure 1). The volcanic islands are located between the Comoros Basin to the south and the Somali Basin to the north (Figure 1) and their activity started during the Miocene after the Mesozoic opening of the Mozambique Channel. The Somali Basin is considered to be underlain by oceanic crust, based on sonobuoy experiments and reflection seismic data [Coffin et al. 1986; Sauter et al. 2018]. An oceanic nature is also known from magnetic anomalies trending WSW–ENE, which indicate the oldest oceanic crust to be of Jurassic age, about 150 Ma [Rabinowitz et al. 1983; Davis et al. 2016; Phethean et al. 2016]. The age and nature of the crust beneath the Comoros Basin and the archipelago is a matter of ongoing debate. The area has been proposed to contain an abnormal oceanic crust [Talwani 1962], a thinned continental crust [Roach et al. 2017], or a normal oceanic crust [Klimke et al. 2016]. Based on one receiver function computation, it has been proposed that the Comoros Archipelago may be built on an isolated block of continental crust [Dofal et al. 2021]. The origin of volcanism within the Comoros Archipelago is also the subject of debate, with proposals linking the islands to a mantle plume [the “hotspot” model, e.g., Class et al. 1998], or to a diffuse or incipient tectonic plate boundary [Michon 2016; Famin et al. 2020; Feuillet et al. 2021].

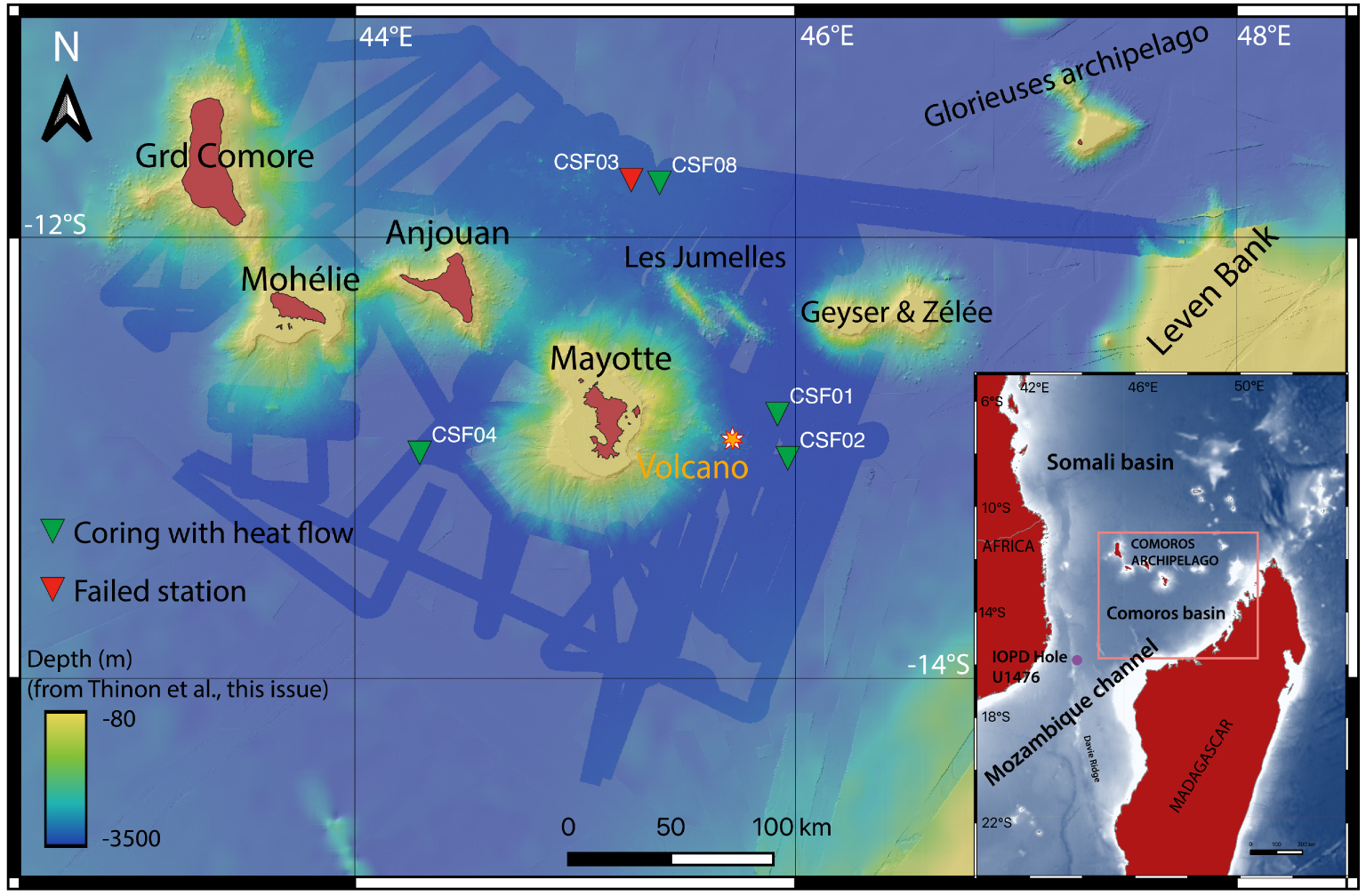

Location of heat flow measurements (green triangles) acquired during SISMAORE relative to bathymetric data compilation [Thinon et al. 2022]. A submarine volcano formed during the 2018–2021 eruption (called New Volcano Edifice) is shown with an orange star [Feuillet et al. 2021]. The inset shows the Somali and Comoros basins as well as the location of IODP site U1476.

The remarkable reports of submarine volcanic activity since May 2018 east of Mayotte, at the eastern end of the Comoros Archipelago [Figure 1, Lemoine et al. 2020; Feuillet et al. 2021; Cesca et al. 2020], have stimulated a number of sea and land surveys of the area [e.g., Rinnert et al. 2019, REVOSIMA, 2021]. To better understand the geodynamics of the Northern Mozambique Channel, geophysical and geological data were acquired during the 2020–2021 SISMAORE cruise [Thinon et al. 2020, 2022]. In this article, we focus on heat flow measurements acquired during the SISMAORE cruise at four stations (Figure 1), using a sediment corer equipped with autonomous thermal sensors. We present these measurements and then compare them with the few existing measurements of surface heat flow in the Northern Mozambique Channel [von Herzen and Langseth 1965], in order to assess models for the nature of the crust and the origin of volcanic activity in this area.

2. Heat flow measurements

2.1. Methods

Heat flow density represents the Earth’s heat loss per surface unit and can be obtained from the Fourier law as the product of the vertical temperature gradient and the thermal conductivity of rocks where the gradient is measured. We estimate heat flow using autonomous thermal probes attached to sediment corers with lengths of either 23 m or 12 m. We use four high-precision probes (THP from NKE®) that measure temperature with a precision of 0.005 °C. The four probes are placed along the lower 12 m or 6 m of the 23 m or 12 m core barrels, respectively. The probes measure the water temperature up to the seafloor and then the equilibrium temperature of the sediments after penetration. Because penetration of the probes in the sediment is associated with frictional heating, the temperature is recorded continuously for about ten minutes, which in general is not enough to reach equilibrium but allows its extrapolation. A separate device (S2IP from NKE®) provides pressure and tilt values. Unlike conventional heat flow instruments, thermal conductivity was not measured in situ, but aboard the ship on recovered sediment cores using a needle probe instrument (Hukseflux TPSYS02). The measurement method is based on the transient line source method: from the response to a heating step the thermal conductivity of sediments can be calculated [Von Herzen and Maxwell 1959; Blum 1997]. We measured the conductivity at intervals of about 30 cm all along the sediment cores (Table 1).

Heat flow measurements obtained during the SISMAORE cruise

| Site name | Latitude | Longitude | Water depth (m) | Sediment core length (m) | nT | Thermal gradient (mK/m) | n𝜆 | Thermal conductivity (W/m/K) | Heat flow (mW/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSF01 | −12.7958 | 45.9173 | 3540 | 18.2 | 4 | 46.6 | 35 | 1.01 | 47 |

| CSF02 | −12.9965 | 45.9638 | 3525 | 4.0 | 2 | 240.0 | 12 | 0.98 | 235 |

| CSF04 | −12.9708 | 44.2927 | 3546 | 2.6 | 4 | 50.9 | 9 | 0.89 | 45 |

| CSF08 | −11.7472 | 45.3819 | 3417 | 11.0 | 4 | 49.3 | 34 | 0.85 | 42 |

nT, number of temperature determinations; n𝜆, number of thermal conductivity determinations.

Analysis of the cores shows that recent sediments include siliciclastic, volcanoclastic, and carbonate components. Sedimentation may affect heat flow by decreasing the temperature gradient as a function of the sedimentation rate [e.g., Manga et al. 2012]. Sedimentation rates are estimated at low values of 2–4 cm/1000 yr (Zaragosi, personal communication), comparable to values of 3 cm/1000 yr at IODP site U1476 [see inset Figure 1; Hall et al. 2017] and of 2–5 cm/1000 yr based on the thickness and estimated ages of sediment layers observed on seismic profiles from SISMAORE cruise [Thinon et al. 2022; Masquelet et al. 2022]. Such low rates of sedimentation imply a negligible heat flow correction [Von Herzen and Uyeda 1963; Manga et al. 2012].

2.2. Results at four sites

We measured temperature and thermal conductivity at four sites, using a 23 m corer at sites CSF01 and CSF02 and a 12 m corer at sites CSF04 and CSF08 (Figures 1 and 2, Table 1). The thermal gradient is defined by three or four temperatures at all sites except CSF02, where only two temperatures were measured. We determined the thermal gradient value from a linear regression of the in-situ sediment temperature data. Thermal gradients are in the range of 46–51 mK/m, while mean thermal conductivity is in the range 0.85–1.01 W/m/K.

Temperature–depth and thermal conductivity–depth profiles obtained at each of the four core locations. The black lines indicate the mean thermal gradient derived from a linear regression of all or selected temperature data and extrapolated to the surface. The bottom water temperature measured before the penetration is also shown.

The first two measurements were performed using a 23 m long corer.

CSF01 is located east of Mayotte Island, in the abyssal plain. Good penetration resulted in a sediment core 18.2 m long. A linear thermal gradient is defined by three temperatures, whereas a fourth, higher value at a depth of 16.9 m lies above the linear trend (Figure 2). This value occurs too deep below seafloor to invoke the effect of bottom water temperature variations on sediment equilibrium temperatures [Davis et al. 2003]. We note a change in thermal conductivity at this depth, with values higher than 1.8 W/m/K (Figure 2). The high conductivity values could be related to siliciclastic sediments prone to fluid circulation and potential temperature perturbations [Vasseur et al. 1993; Poort and Polyansky 2002]. We exclude the high temperature value at 16.9 m to calculate a linear thermal gradient of 46.6 mK/m. Thermal conductivity within the core varies from 0.71 to 1.89 W/m/K, which is high but cannot account for the thermal non-linearity observed at 16.9 m (Figure 2, Table 1). The mean thermal conductivity is 1.01 W/m/K, higher than in the other cores, which is probably related to the low porosity of the sediments. The core contains a record of hemipelagic sedimentation with turbidites. The estimated heat flow for CSF01 is 47 mW/m2.

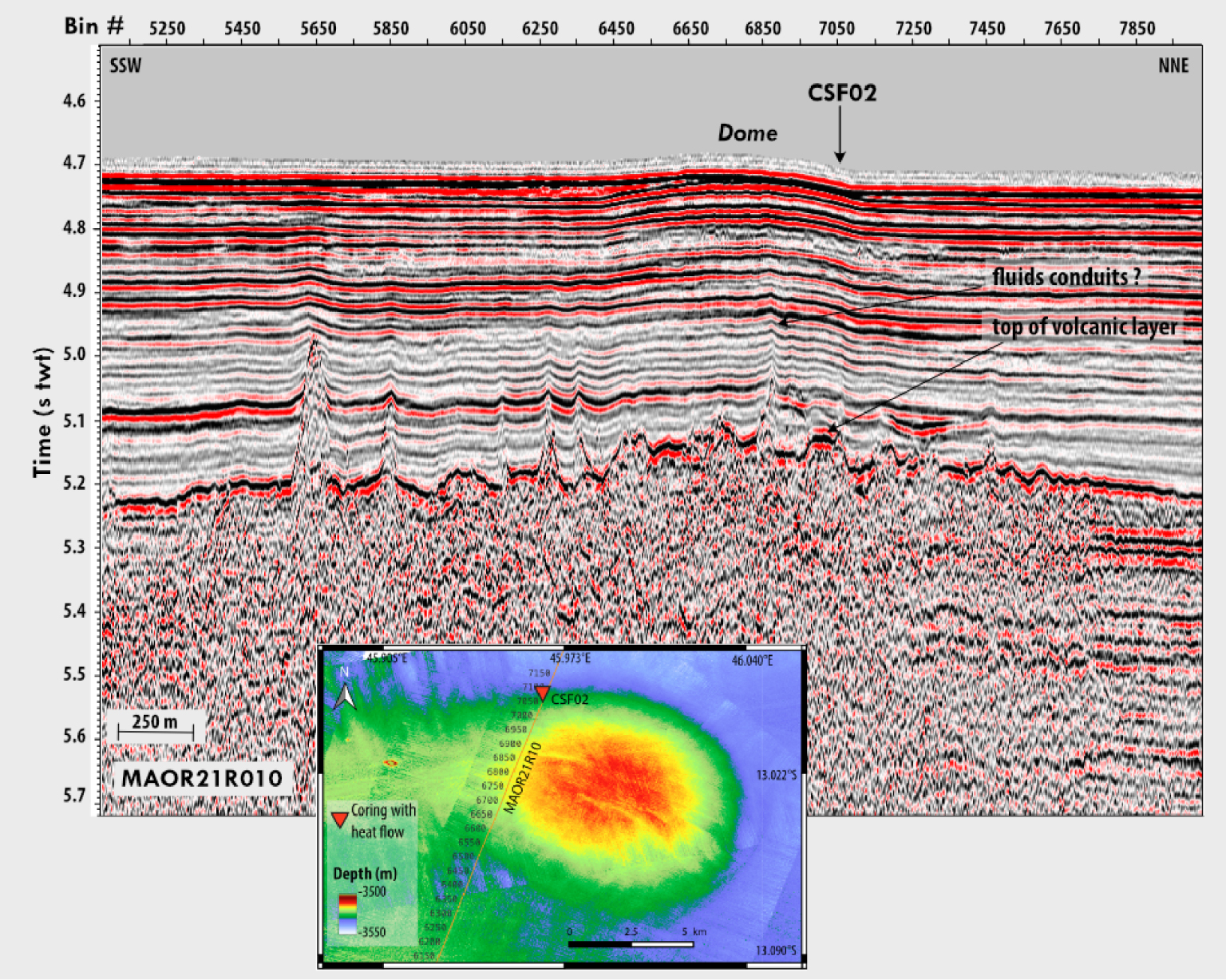

CSF02 is also located east of Mayotte, on the border of a topographic dome 10 km in diameter and 30 m in height (Figure 3). In volcanic areas, such morphology corresponds to a forced fold, often related to the intrusion of a saucer-shaped sill at depth and described in various geological contexts [Jackson et al. 2013; Medialdea et al. 2017; Magee et al. 2017], as well as experimentally reproduced [Galland 2012]. On a seismic profile across the site, we observe that doming affects the underlying sedimentary succession (0.5 s twtt) down to an older volcanic layer that affects the seismic image and precludes sill localization (Figure 3). The morphological expression at the seabed suggests that the sill intrusion occurred in recent geological time, though it is not possible to be precise before the validation of a proper local age model. The forced fold lies at the eastern end of a WNW-ESE active volcanic ridge, the Eastern Volcanic Chain of Mayotte, 30 km east of the new Volcano Edifice [orange star in Figure 1; Paquet et al. 2019; Thinon et al. 2022; Deplus et al. 2019; Feuillet et al. 2021]. The penetration of the corer at site CSF02 was low as it stopped on a sandy quartzitic layer (6 m for a 23 m barrel). Due to this low penetration, temperatures were measured at only two sensors. The thermal gradient is therefore poorly constrained, but is very high at 240 mK/m. The mean thermal conductivity is 0.98 W/m/K, yielding a high heat flow of 235 mW/m2 (Figure 2, Table 1), maybe linked to the presence of the underwater volcano (Figure 1) but a new measurement is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Seismic reflection profile crossing the location of core CSF02, at the edge of a topographic dome (location shown on inset bathymetric map). The dome is underlain at depth by a basaltic layer and possible fluid conduits are imaged in the overlying sediment succession that may record the vertical migration of fluids.

Following loss of the 23 m corer and temperature probes at the site CSF03 (Figure 1), the following heat flow measurements were obtaining using a 12 m corer. CSF04 is located west of Mayotte in the Comoros Basin. Complete penetration of the corer resulted in temperature measurements in all four sensors. Nonetheless, due to technical problems, the sediment core recovered was very short (2.6 m). The thermal gradient is 50.9 mK/m, and the mean thermal conductivity of the shallow sediments is 0.89 W/m/K. Despite the fact that we only determined the conductivity in the upper part of the core, this value falls in the range of the mean conductivities measured at the other sites (Figure 2, Table 1). The heat flow estimate for CSF04 is 45 mW/m2.

CSF08 is located North of Mayotte in the Somali Basin. Good penetration resulted in a core length of 11 m. The sediment core contains a record of hemipelagic sedimentation with turbidites. The thermal gradient is 49.3 mK/m and the mean thermal conductivity is 0.85 W/m/K (Figure 2, Table 1). The heat flow for CSF08 is estimated to be 42 mW/m2.

3. Discussion

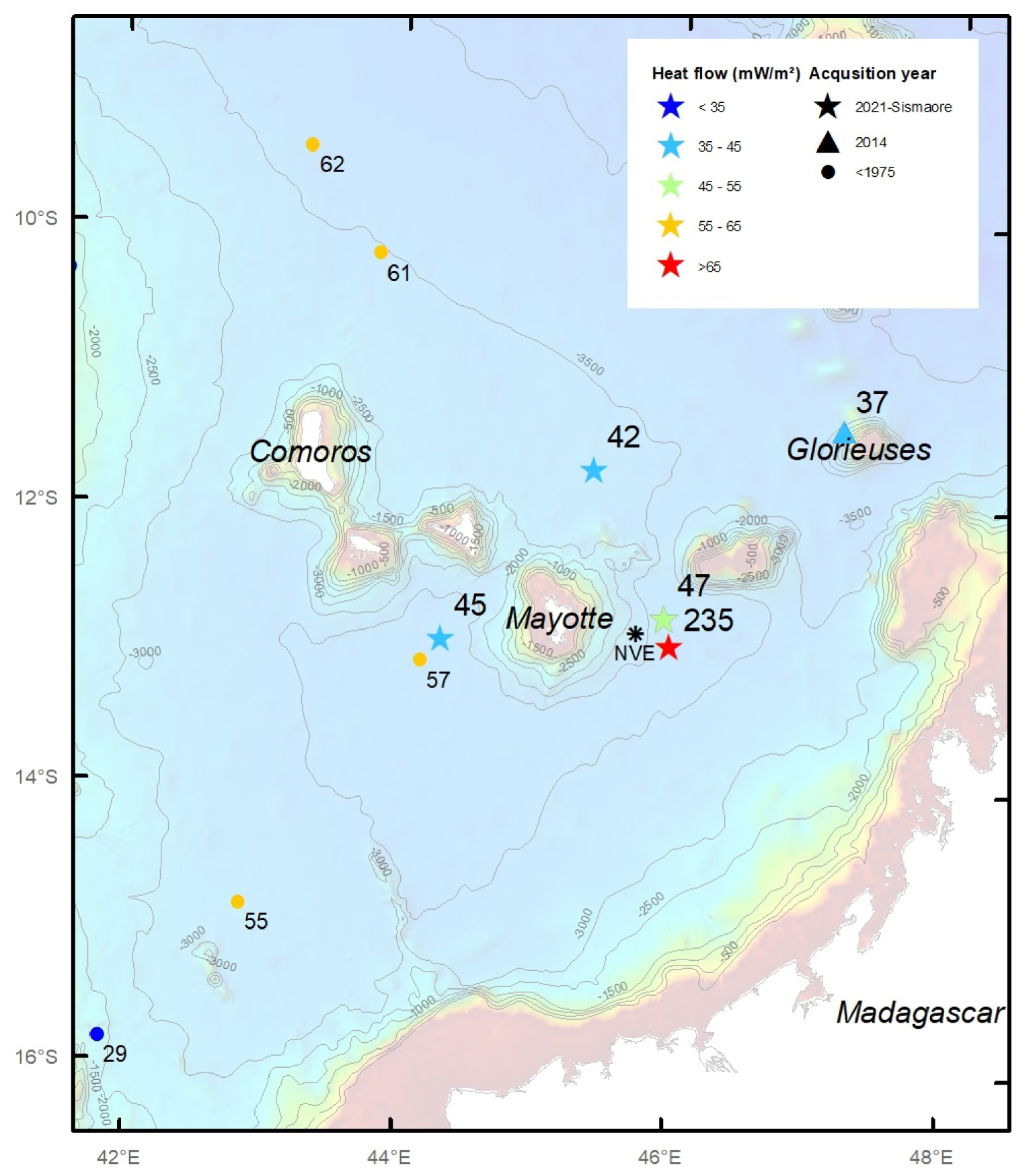

The heat flow measurements from the SISMAORE cruise add to the regional understanding of the Northern Mozambique Channel, where only six measurements have previously been acquired (Figure 4). Five of these heat flow values come from the NGHF database [Lucazeau 2019] and date from the 1960–70s (Table 2). One is a value of 29 mW/m2 obtained in the Davie Ridge during DSDP leg 25 [Marshall and Erickson 1974]. Two measurements in the Somali Basin provide heat flow values of 61 and 62 mW/m2 [von Herzen and Langseth 1965], while two measurements in the Comoros Basin have values of 57 and 55 mW/m2 [von Herzen and Langseth 1965]. In addition, during the recent PAMELA-MOZ1 cruise [Olu 2014; Jorry et al. 2020], a heat flow measurement of 37 mW/m2 was obtained close to the Glorieuses Islands (Table 2, Figure 4). Our new measurements include heat flow values of 47, 45 and 42 mW/m2 for sites CSF01, CSF04 et CSF08 (Table 1, Figure 4). Taken together, available data from the Northern Mozambique Channel concur that regional heat flow is low.

Bathymetric map of the Northern Mozambique Channel with previous heat flow measurements (colored dots) from the NGHF database [Lucazeau 2019] and from the PAMELA-MOZ1 survey (colored triangle) [Olu 2014], along with our new measurements (colored stars) from SISMAORE. The submarine volcano NVE (New Volcano Edifice) formed during the 2018–2021 eruption is shown with a black star.

Heat flow measurements from previous cruises

| Site name | Latitude | Longitude | Thermal gradient (mK/m) | Thermal conductivity (W/m/K) | Heat flow (mW/m2) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V19-98 | −9.4666 | 43.3167 | 68.8 | 0.90 | 62 | Herzen and Langseth [1965] |

| V19-99 | −10.2317 | 43.8166 | 67.0 | 0.91 | 61 | Herzen and Langseth [1965] |

| V19-100 | −13.1333 | 44.1499 | 65.2 | 0.88 | 57 | Herzen and Langseth [1965] |

| V19-101 | −14.8833 | 42.8500 | 57.8 | 0.96 | 55 | Herzen and Langseth [1965] |

| KSF06 | −11.4400 | 47.1850 | 38.8 | 0.96 | 37 | Olu [2014] |

It is of interest to compare our heat flow value of 45 mW/m2 at site CSF04 in the Comoros Basin with a nearby older measurement at site V19-100 (Figure 4), which yielded a heat flow of 57 mW/m2 [von Herzen and Langseth 1965]. Thermal conductivity values at the two sites are similar (0.88 W/m/K versus 0.89 W/m/K, Tables 1 and 2), whereas the thermal gradient is higher for the older measurement (65.2 mK/m versus 50.9 mK/m, Tables 1 and 2). All the older measurements (Figure 4, sites V19 in Table 2) were acquired using a shorter (2 m) corer and only two thermal probes, whereas we used four probes at depths below seafloor greater than 6 m (Figure 2). Therefore, the older gradient measurements have much higher uncertainties because of possible perturbations by deep-ocean temperature variations [Davis et al. 2003] and because of technical bias before 1990 [Lucazeau 2019]. The higher heat flow at the older sites is much less reliable than the values obtained with more recent and longer instruments.

We obtained heat flow values of 42 mW/m2 in the Somali Basin, of 45 mW/m2 in the Comoros Basin, and of 47 mW/m2 east of Mayotte within the Cormoros archipelago. Our values are consistent with an oceanic lithosphere of Jurassic age, for which the mean global heat flow is 51 ± 11 mW/m2 [Lucazeau 2019]. The value of 37 mW/m2 measured recently near the Glorieuses Islands, where receiver functions indicate an oceanic crust with a shallow Moho at 11 km depth [Dofal et al. 2021], is lower than this global mean, while our new value of 42 mW/m2 in the Somali basin is at the lower end of the global mean. In the Comoros Basin, a comparable value of 45 mW/m2 could also point to an oceanic crust of Jurassic age in this area. However, from a thermal point of view, it is difficult to differentiate old oceanic crust from thinned continental crust for which heat production contribution is weak [e.g., Louden et al. 1997].

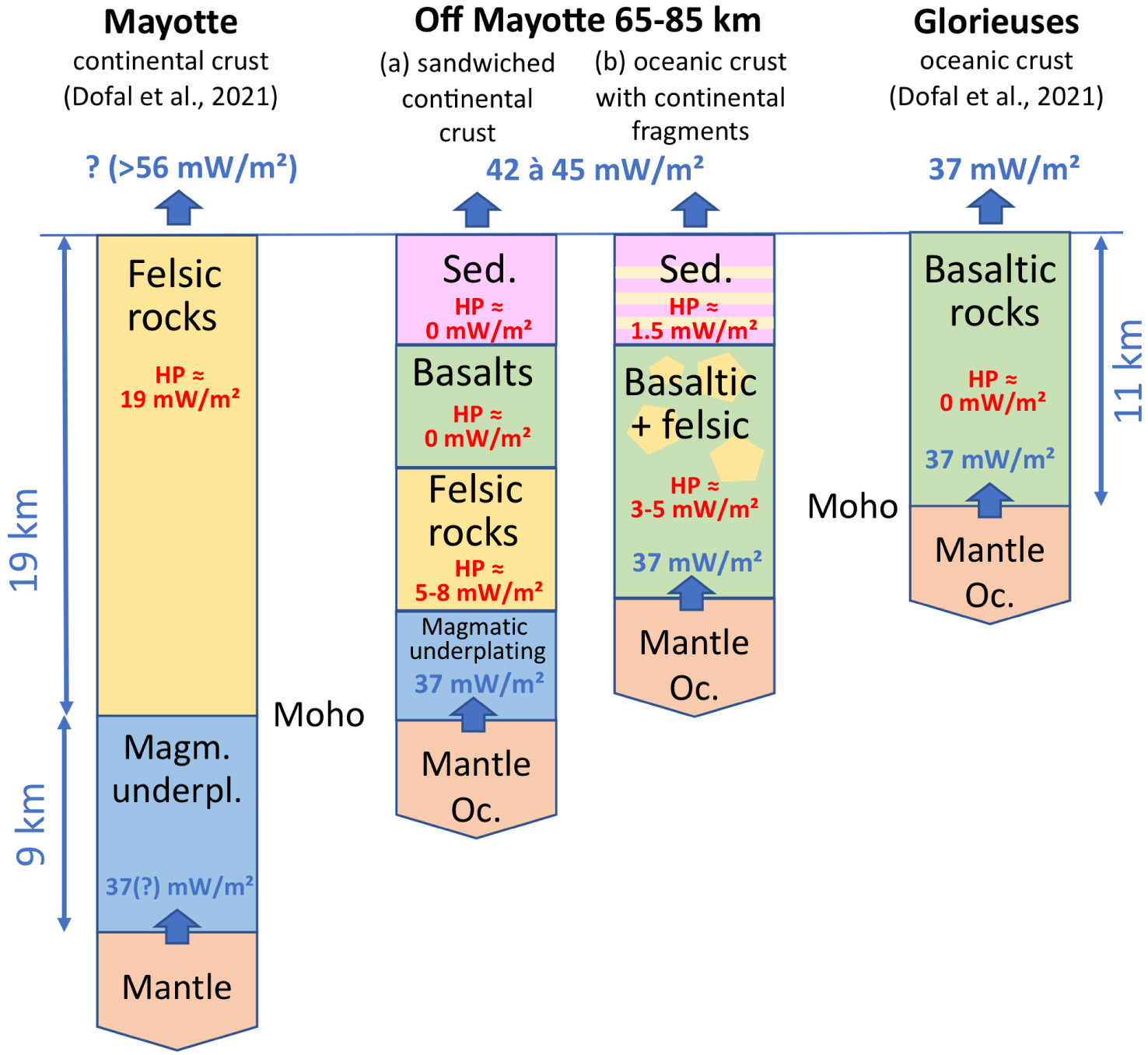

From a receiver function study [Dofal et al. 2021], it was proposed that the crust under Mayotte is of continental nature, with a thickness of 19 km, and is underlain by magmatic underplating, with a 27-km deep Moho. This implies a surface heat flow of not less than 56 mW/m2 if we apply a mean value of crustal heat production of 1 μW∕m3 [Hasterok and Webb 2017]: 19 mW/m2 due to radiogenic heat production in the crust and 37 mW/m2 from mantle input as observed at the Glorieuses Islands (Figure 5). Our data indicate lower heat flow values of 42–47 mW/m2 at a 65–85 km distance of Mayotte, implying that the proposed continental block under Mayotte Island is of limited lateral extent. New investigations by Dofal et al. [2022] do not provide conclusive data on the nature of the crust, that could be either an abnormally thick oceanic crust or a thinned continental crust abandoned during the southern drift of Madagascar.

Conceptual sketch showing two hypotheses (two central columns) for the structure of the crust off Mayotte, both consistent with heat flow data, compared to heat flow measured or expected for Mayotte and Glorieuses Islands and based on information on crustal structure from Dofal et al. [2021]. See text for discussion.

We propose two hypotheses for the crust off Mayotte that are in agreement with the heat flow observations (Figure 5): (a) a very thin continental crust of felsic material overlain by effusive basalts, and perhaps underplated by basalts as for Mayotte, or (b) a basaltic oceanic crust, with additional heat production from incrusted continental fragments and/or from quartz-rich sediment eroded from the nearby island [Flower and Strong 1969]. Heat flow data alone cannot discriminate between these models, and the nature of the crust off Mayotte needs to be further defined by seismic methods.

At a regional scale, the low heat flow does not represent a thermal signature that can be readily associated with a mantle plume. A “hotspot” model has been proposed for the Comoros Archipelago [e.g., Class et al. 1998], but has been questioned by several authors [see discussions in Michon 2016; Thinon et al. 2022]. On the one hand, heat flow anomalies on hot spot swells are small and sometimes difficult to constrain [Bonneville et al. 1997]. On the other hand, our measured heat flow lie in the lower range of those for Jurassic oceanic lithosphere [Hasterok 2013; Lucazeau 2019], and thus do not support a regional thermal anomaly.

Since May 2018, submarine volcanic activity has been taking place 50 km east of Mayotte, with evidence of a large eruption [Lemoine et al. 2020; Cesca et al. 2020; Feuillet et al. 2021; Berthod et al. 2021a, b; Deplus et al. 2019]. These studies all indicate a deep reservoir of magma (>55 km depth), which is migrating to the surface through dykes that intrude the lithosphere. Due to slow thermal diffusivity, such a deep reservoir has no present-day thermal signature at the Earth’s surface. As exemplified in the Gulf of Aden, to produce a high heat flow at the surface the emplacement of the heat source must be both shallow and recent [Lucazeau et al. 2009]. As presented above, we have one very high heat flow measurement of 235 mW/m2, at site CSF02, 30 km east of the active volcano (NVE, Figure 4). This value is not representative of regional heat flow but is clearly the result of a local process. Several factors suggest that it can be linked with the circulation of hot fluids. The measurement is aligned with the eastern Volcanic Chain of Mayotte and located at the border of a recent forced fold, 10 km wide and 30 m high, underlain by a magmatic sill (Figure 3). Seismic reflection data from SISMAORE cruise show conduit-like features or chimneys within the sedimentary succession that may record the vertical migration of fluids towards the surface in the area [Masquelet et al. 2022]. Upward migration of hot fluids could be triggered by the renewed activity at the east Volcanic Chain of Mayotte, or by the recent sill intrusion that formed the forced fold.

4. Conclusions

Heat flow measurements acquired in the Northern Mozambique Channel during the SISMAORE cruise are low, with values in the range of 42–47 mW/m2. Together with other recent data in the area, these values are among the lowest heat flow reported for oceanic lithosphere of Jurassic age. Regarding the nature of the crust, two hypotheses are proposed that fit with the new heat flow data. The first is that off Mayotte the crust is mainly oceanic, with some heat production from felsic continental fragments in the crust or in sedimentary deposits. The second is that the crust is composed of a thin continental layer overlain by effusive basalts and possibly underplated as proposed for Mayotte. The low regional heat flow observed in the Northern Mozambique Channel appears inconsistent with a mantle plume. One very high heat flow value of 235 mW/m2 at a site 30 km east of the active volcano is believed to be related to the circulation of hot fluids induced by the recent magmatic activity, maybe by the latest pulse that started in 2018 east of Mayotte.

Conflicts of interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

We thank Captain P. Moimeaux, the crew and technicians from R/V Pourquoi Pas ? (FOF by Ifremer/ GENAVIR), and the scientific COYOTES and SISMAORE teams. The SISMAORE cruise (https://doi.org/10.17600/18001331) is mainly funded by the FOF (Flotte Océanographique Française), the French Geological Survey (BRGM) and the COYOTES project (Agence Nationale de Recherche; ANR-19-CE31-0018). The Pamela-MOZ1 heat-flow measurement comes from the PAMELA project (PAssive Margin Exploration Laboratories) which is a scientific project led by Ifremer and TotalEnergies in collaboration with Université de Bretagne Occidentale, Université Rennes, Sorbonne Université, CNRS and IFPEN. Finally, we thank the two reviewers, Alain Bonneville and Daniel Praeg, for their valuable comments and suggestions.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0